Annotated Bibliography

Compiled by Catherine Whalen and Irene Hollister; annotated by Catherine Whalen, Susie Silbert, and Colleen Terrell.

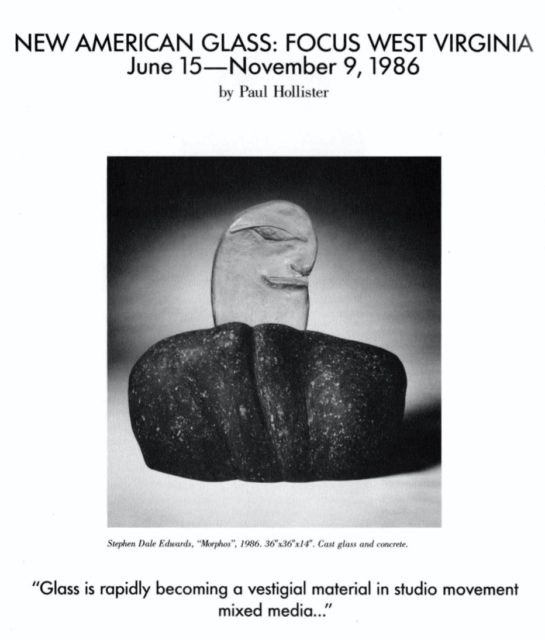

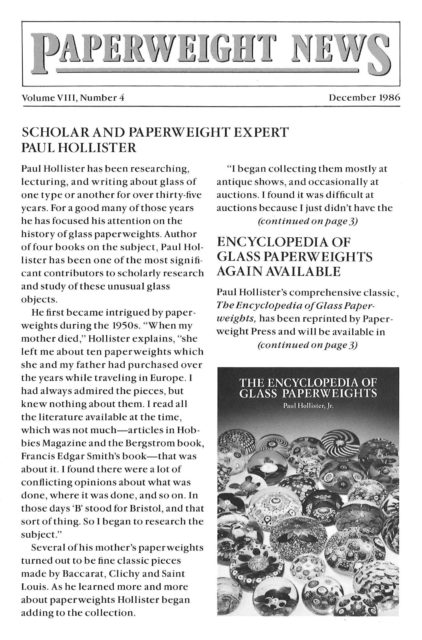

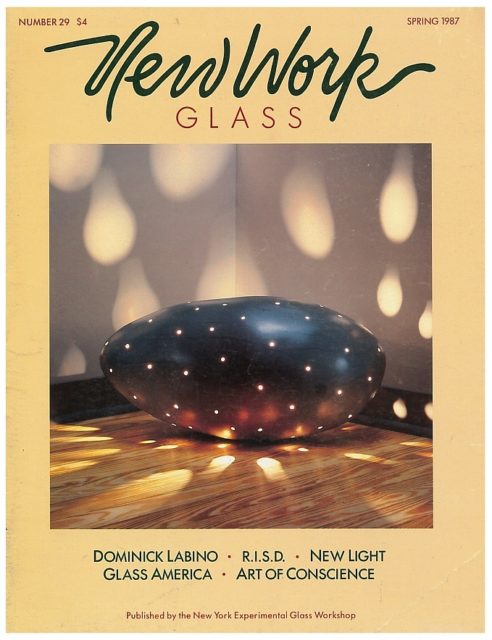

This comprehensive annotated bibliography brings together Paul Hollister’s critical writings on studio glass, published between 1976 and 1995. The majority appeared in periodicals: the New York Times, Neues Glas, Collector Editions (previously Acquire), American Craft, Glass (previously New Work), The Glass Club Bulletin, Glass Art Society Journal, and Ontario Craft. Hollister also contributed to the exhibition catalogues Paperweights: “Flowers which clothe the meadows”, Americans in Glass, and New American Glass: Focus 2 West Virginia; the anthology Glass State of the Art 1984; and Annales du 11e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre. Rounding out the 90 entries are articles about Paul Hollister and Irene Hollister, published in the Journal of Glass Studies, Glass, and Paperweight News.

Each entry features a link to a downloadable PDF or online source for that writing, a list of people and places mentioned, and links to pertinent pages on this site. Several entries reference relevant interviews and lectures that Paul Hollister recorded for research purposes. See linked names for Bard Graduate Center transcripts of these audio recordings, which are held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass.

Jump to 19751975

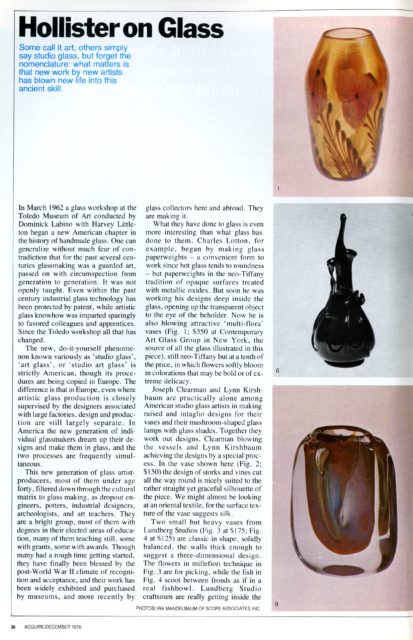

“Hollister on Glass.” Acquire 4, no. 5 (December 1976): 26-27. Editor’s note: Acquire subsequently renamed Collector Editions.

“Hollister on Glass.” Acquire 4, no. 5 (December 1976): 26-27. Editor’s note: Acquire subsequently renamed Collector Editions.

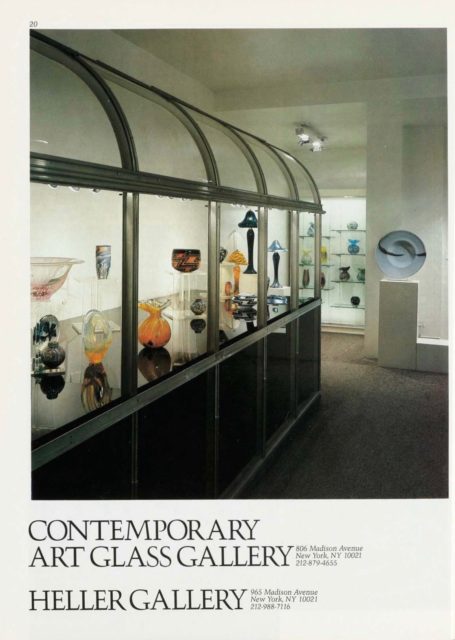

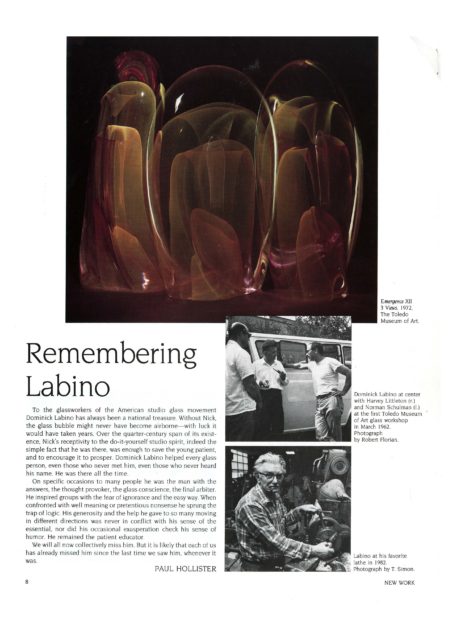

Hollister briefly describes the emergence, following the 1962 glass workshop led by Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino at the Toledo Museum of Art, of a new movement of “art” or “studio” glass in America. The work of a younger generation of individual “glass artist-producers” was gaining acceptance, exhibition exposure, and interest from museums and collectors. Hollister details and assesses an assortment of vases and bottles—some verging on “piece[s] of sculpture in traditional disguise”—by seven artists and two glass studios, all of which can be found at Contemporary Art Glass Group in New York City. He particularly admires work by James Daniel, William Carlson, and Tom Patti and predicts that a small laminated vase by Patti will be repeatedly illustrated in contemporary-glass publications. Incl. prices and illus. (5 b/w, 5 color) of work by Michael Boylen, William Carlson, Joseph Clearman, James Daniel, David Donaldson, Lynn Kirschbaum, Charles Lotton, Lundberg Studios, Tom Patti, and Mark Peiser.

Michael Boylen, William Carlson, Joseph Clearman, Contemporary Art Glass Group [later Heller Gallery], James Daniel, David Donaldson, Lynn Kirschbaum, Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton, Charles Lotton, Lundberg Studios, Tom Patti, Mark Peiser, Tiffany, Toledo Museum of Art

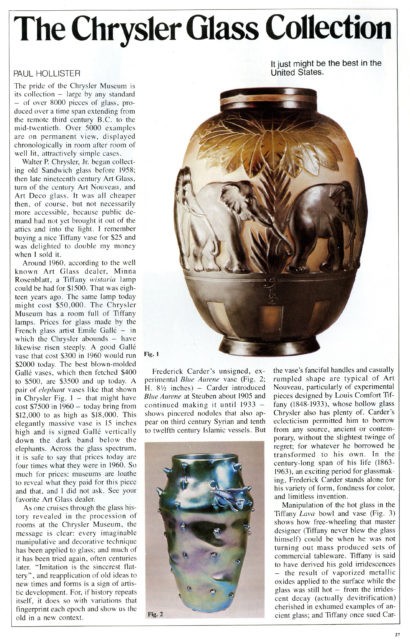

“The Chrysler Glass Collection.” Collector Editions 6, no. 2 (Spring 1978): pp. 27-29.

“The Chrysler Glass Collection.” Collector Editions 6, no. 2 (Spring 1978): pp. 27-29.

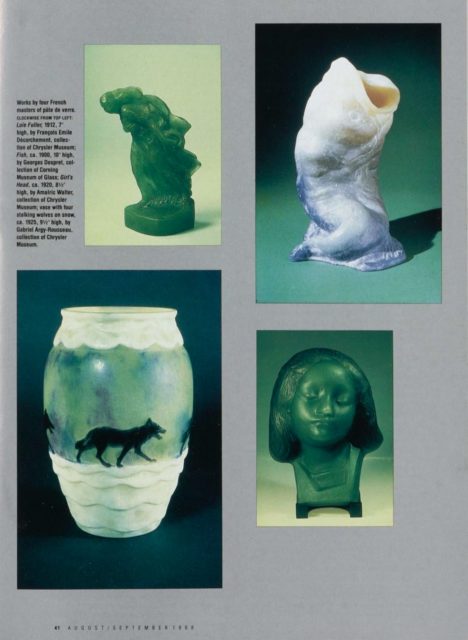

Hollister provides a brief overview of the scope, layout, and installation of the Chrysler Museum’s 8,000-piece encyclopedic glass collection (5,000 works on view) initiated by a gift from Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. Hollister outlines the arc of Chrysler’s glass collecting with an emphasis on the current desirability of his acquisitions of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century glass. Work by masters of this era including Frederick Carder, Auguste Daum, Émile Gallé, René Lalique, Gabriel Argy-Rousseau, and Louis C. Tiffany—whom Hollister identifies for their ability to adapt historical precedent in service of an individualized artistic view—dominate the text. The article concludes with a barb aimed at contemporary glassworkers rehashing these older styles: “The Art Brand-Nouveau of today is a pale, stale apeing of what was once crammed with imagination and technical knowhow that characterizes the real thing.” Incl. prices and illus. (7 b/w, 6 color) of work by Gabriel Argy-Rousseau, Frederick Carder, Auguste Daum, Émile Gallé, and Louis C. Tiffany.

Argy-Rousseau, Frederick Carder, Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Chrysler Museum, Gustave Courbet, Daum, Lalique, Gallé, George Innes, Minna Rosenblatt, Steuben, Tiffany

“The Great Paperweight Show at Corning.” Collector Editions 6, no. 3 (Summer 1978): pp. 28-29.

“The Great Paperweight Show at Corning.” Collector Editions 6, no. 3 (Summer 1978): pp. 28-29.

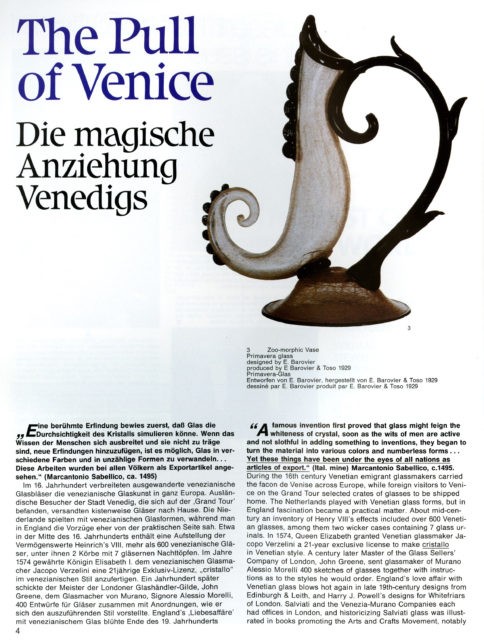

The review of The Great Paperweight Show at The Corning Museum of Glass (April 29–October 21) deems it a jewellike “once-in-a-lifetime exhibition.” It features 300+ weights drawn from museum and private collections, notably that of Armory Houghton, chairman emeritus of Corning Glass Works. Hollister admires the museum’s scholarly approach and the show’s dramatic and instructive installation, including attention to weights whose makers incorporated “ancient glass techniques” in their designs. Dwight P. Lanmon, Corning’s deputy director of collections, and Hollister both selected weights for the exhibition and coauthored its catalogue. Hollister begins his review with the quotation, “Consider to whom did it first occur to include in a little ball all the sorts of flowers which clothe the meadows in the spring.” The exhibition catalogue, Paperweights: “Flowers which clothe the meadows,” uses a shortened version. Although not specified, the source of the quote is Marc Antonio Sabellico, a fifteenth-century historian of Venice who wrote about the glass industry on the island of Murano, referencing the technique of millefiori (“a thousand flowers,” in Italian). As Hollister explains, “Rods of colored glass are shaped, fused together to form cane designs, stretched to great lengths while still plastic, and finally sliced to reveal miniaturization of the original designs.” He concludes by quoting several collectors at length, providing insights into motivation, connoisseurship, and the market. Incl. prices and illus. (7 color) of work by Baccarat, Clichy, Gillinder, and Saint-Louis.

Art Institute of Chicago, Baccarat, Bergstrom-Mahler Museum of Glass, Clichy, Corning Glass Works [later Corning Incorporated], The Corning Museum of Glass, Gillinder, Amory Houghton, Dwight Lanmon, New-York Historical Society, Rubloff Collection, Saint-Louis

“Paperweights and Related Objects Included in ‘The Great Paperweight Show,’ Not Listed in the Catalogue.” Corning, NY: Corning Museum of Glass, 1978.

“Paperweights and Related Objects Included in ‘The Great Paperweight Show,’ Not Listed in the Catalogue.” Corning, NY: Corning Museum of Glass, 1978.

The text is an addendum to Paul M. Hollister and Dwight P. Lanmon, Paperweights: “Flowers which clothe the meadows” (Corning, NY: Corning Museum of Glass, 1978), the catalogue accompanying The Great Paperweight Show of 1978, organized by The Corning Museum of Glass. Lanmon and Hollister collaborated on selecting 300+ paperweights for the exhibition and preparing the 167-page catalogue, for which the latter wrote the accompanying essay and commented upon the 78 color plates. This list enumerates an additional 69 items, including 29 contemporary paperweights dating from 1973 through 1978, chosen by Hollister. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded material related to this publication. See linked pages for Dwight Lanmon and The Corning Museum of Glass for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recordings held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Paul Hollister and Dwight Lanmon Lectures, May 17, 1986 (Corning BIB ID: 167926).

Baccarat, Bakewell, Page & Bakewell, Robert Bartlett, Bob Banford, Ray Banford, Andre Billeci, John Bingham, The Corning Museum of Glass, William Carlson, Clichy, Cristal D’Albret, Max Roland Erlacher, Josephinenhütte, Charles Kaziun, James Kontes, Dominick Labino, Dwight Lanmon, John Lewis, Charles Lotton, Nicholas Lutz, Milropa Studios, Orient and Flume, Tom Patti, Aspley Pellatt, Perthshire Paperweights, Gilbert Poillerat, Richard Ritter, Saint-Louis, Paul Seide, Bruce Sillars, Carolyn Marie Smith, Hugh Edmund Smith, Paul Stankard, Debbie Tarsitano, Thurston Studio, Charles Wright, Paul Ysart

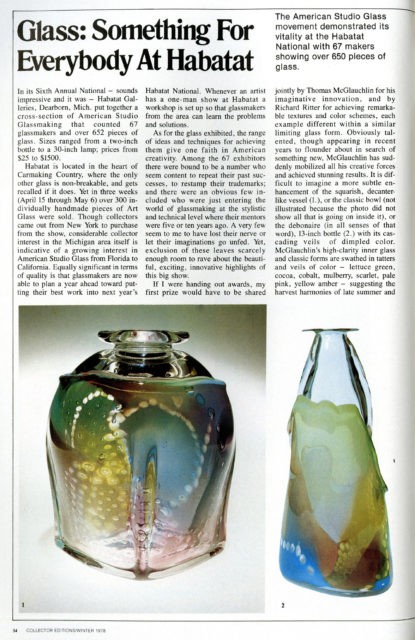

“Glass—Something for Everybody at Habatat.” Collector Editions 6, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 34–38.

“Glass—Something for Everybody at Habatat.” Collector Editions 6, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 34–38.

Sixty-seven artists are represented by 652 pieces in this “cross-section of American Studio Glassmaking” on view at the 6th annual national survey exhibition at Habatat Galleries in Dearborn, Michigan (1820 N. Telegraph Road, April 15–May 6, 1978). Hollister finds much to like in this big show and describes some of its “beautiful, exciting, innovative highlights.” He emphasizes technical precision, noting artists such as Paul Manners who are not content to “work with dishwater glass,” and he highlights glassmakers such as Tom McGlauchlin, Richard Ritter, George Thiewes, Charles Wright, and Judy Kelmen, whom he feels are pushing themselves artistically. Hollister’s writing manifests the vivid metaphors and the often wry, sometimes mischievous tone especially evident in his early reviews. When he praises Robert Bartlett’s cross-banded, cube-shaped cast-glass bottles for their originality, for example, he describes them as containing “mysterious internal essences in which imaginary forms appear to float and languish like pickled specimens. Is it a turnip? A registered nurse’s wravelled stocking? A hermit crab seen by X-ray in its shell?” Hollister also discusses collectors and the emerging market. Sizes and types of objects range from “a two-inch bottle to a 30-inch lamp,” and prices between $25 and $1,500. Incl. prices and illus. (11 color) of work by John Bingham, Janet Kelman, John Lewis, Paul Manners, Tom McGlauchlin, Joel Philip Myers, Richard Ritter, George Thiewes, Charles Wright, and Brent Young.

Baccarat, Robert Bartlett, John Bingham, Michael Boylen, William Carlson, Dale Chihuly, Robert Fritz, Martha Graham, Habatat Galleries, Paul Jenkins, Janet Kelman, John Lewis, Harvey Littleton, Morris Louis, Flora Mace, Paul Manners, Richard Marquis, Brian Maytum, Tom McGlauchlin, Milropa Studios, Joel Philip Myers, Tom Patti, Michael Pavlik, Mark Peiser, Penland School of Crafts [later Penland School of Craft], Arthur Rackham, Richard Ritter, Steuben, George Thiewes, Charles Wright, Brent Young

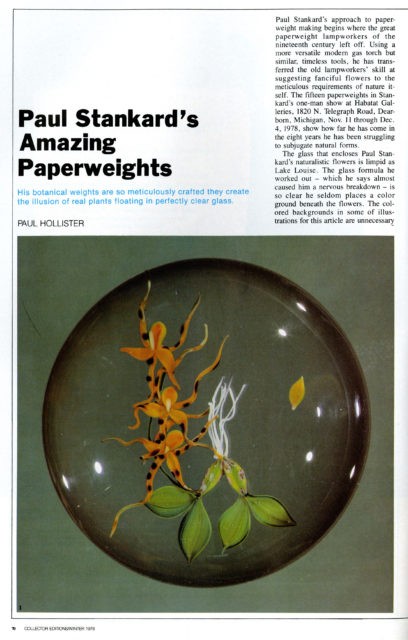

“Paul Stankard’s Amazing Paperweights.” Collector Editions 6, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 70–73.

“Paul Stankard’s Amazing Paperweights.” Collector Editions 6, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 70–73.

The 15 naturalistic floral paperweights on view in Paul Stankard’s solo exhibition at Habatat Galleries in Dearborn, Michigan (1820 N. Telegraph Road, November 11–December 4, 1978) chronicle the artist’s acquisition of skill over his eight-year lampworking career. Hollister explains the scientific research underpinning Stankard’s pieces and gives in-depth descriptions of 13 of the limited and “open” edition paperweights included in the exhibition, naming prices and pricing criteria, length of run, and in some cases, remaining number of pieces. The article appears in the same issue as Hollister’s review of the 6th annual national exhibition at Habatat Galleries (“Glass—Something for Everybody at Habatat”). Incl. prices and illus. (10 color) of work by Paul Stankard.

John Brass, Olga Dahlgren, John Glass, Habatat Galleries, Paul Stankard

“One Glass Show, Two Techniques.” New York Times, December 14, 1978, C2. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2Eg6E0s

“One Glass Show, Two Techniques.” New York Times, December 14, 1978, C2.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2Eg6E0s

Hollister discusses the disparate glassworks of John Nygren and Herb Babcock at the Contemporary Art Glass Group in New York City. Nygren’s diminutive vases depict scenes from nature, often adorned with three-dimensional sculpted renderings of frogs and lizards. Babcock’s work, by contrast, displays a fascination with “gossamer translucency” in three-dimensional forms. Incl. prices and illus. (1 b/w) of work by Herb Babcock.

Herb Babcock, Contemporary Art Glass Group [later Heller Gallery], Max Laeuger, John Nygren

“Glass America 1978 at Lever House.” Collector Editions 7, no. 1 (January 1979): 50–54.

“Glass America 1978 at Lever House.” Collector Editions 7, no. 1 (January 1979): 50–54.

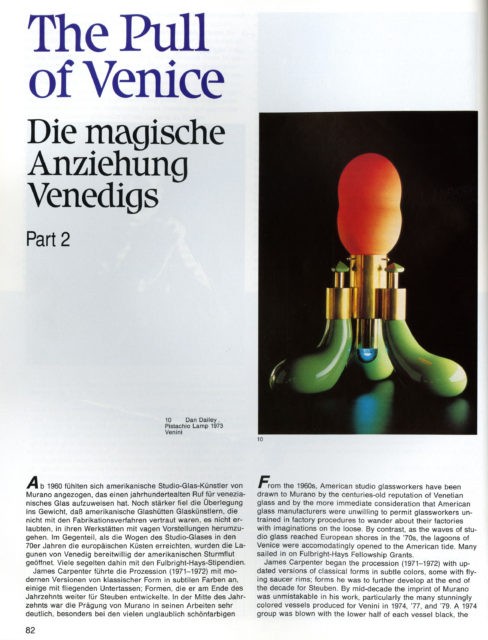

Organized by Douglas Heller and sponsored by his gallery Contemporary Art Glass Group and the Glass Art Society, Glass America 1978’s “handsome display was a cross-section of the work of 50 American glassmakers, which included glass for every taste and pocketbook” ($60 to about $2,000). A follow-up to Heller’s Contemporary Art Glass 1976, likewise held in the atrium of the “glass sheathed” Lever House building in midtown Manhattan, this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue cemented the gallery’s role as an arbiter of taste on a national scale and prompted purchases by prominent institutions as well as private collectors. Techniques range from blowing, lampworking, lamination, and slumping to plate and stained glass. The latter includes Leifur Breidfjord’s huge “glass tapestry” and Ray King’s 18-foot “abstract screen,” both intended as inducements for commissions. Hollister praises and critiques Tom Patti’s Solar Bronze Riser, the “miniature monument” in laminated glass pictured on the show catalogue’s cover and subsequently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. Harvey Littleton, Hans Frabel, Mary Shaffer, and others present sculptural work. Steven Weinberg’s “small yet massive” frosted-glass objects are “packed with power,” both original and skillfully executed. Hollister admires vases by Tom McGlauchlin, David Hutchthausen, Herb Babcock, Richard Ritter, and Dan Dailey, and he describes Dale Chihuly’s “casually strewn and nested glass baskets” as “pleasantly offbeat.” Incl. prices and illus. (6 b/w, 5 color) of work by Dale Chihuly, Hans Godo Fräbel, David Huchthausen, Harvey Littleton, Ray King, Tom McGlauchlin, Karel Mikolas, Tom Patti, Richard Ritter, Mary Shaffer, and Steven Weinberg.

Ansel Adams, Herb Babcock, Leifur Breidfjord, Dale Chihuly, Contemporary Art Glass Group [later Heller Gallery], Dan Dailey, Hans Godo Fräbel, Glass Art Society, Douglas Heller, David Huchthausen, Harvey Littleton, John Lewis, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Ray King, Smithsonian Institution, Tom McGlauchlin, Karel Mikolas, Tom Patti, Art Reed, Richard Ritter, Mary Shaffer, Steven Weinberg

“At Corning Glass Show, Sculptural Whimsy.” New York Times, April 26, 1979, C8. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V2RmBW

“At Corning Glass Show, Sculptural Whimsy.” New York Times, April 26, 1979, C8.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V2RmBW

While comparable to his Collector Editions review (vol. 7, no. 4, Fall 1979) on The Corning Museum of Glass exhibition New Glass 1979, Hollister is more critical in tone and more specific in his likes and dislikes in this short piece. He emphasizes international contributions, especially those from Czechoslovakia that, despite only having 24 entrants, “dominate[d] the show”; he mentions only Roberto Moretti and Hans Godo Fräbel (whom he calls “a natural” for his surrealist Hammer) from the United States. Questioning the timidity of the jurors, Hollister designates the exhibition as “neither as large, experimentally broad-ranged nor as colorful as the all-European Coburg Glass Prize 1977 show.” Nonetheless, “there are plenty of pieces to marvel at.” Incl. illus. (1 b/w) of work by Hans Godo Fräbel. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist pages for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recordings held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Paul Hollister Self-recording, April 11, 1979 (Corning BIB ID: 168418).

Blanka Adensamová, Karl Berg, Thomas Buechner, The Corning Museum of Glass, Torres Esteban, Ulla Forsell, Lars Hellsten, Pavel Hlava, Hans Godo Fräbel, Věra Lišková, Jean-François Millet, Roberto Moretti, Pilgrim Glass, Miluse Roubícková, Ivo Rozsypal, Fumio Sassa, Lubov Savelieva, Helmut Schäffenacker, Livio Seguso, Steuben, William Warmus

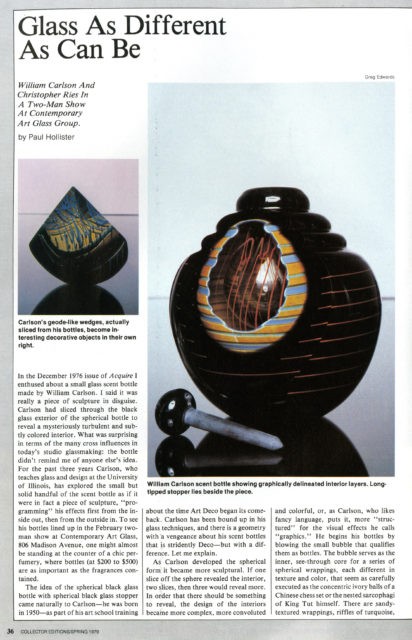

“Glass As Different As Can Be.” Collector Editions 7, no. 2 (Spring 1979): 36–38.

“Glass As Different As Can Be.” Collector Editions 7, no. 2 (Spring 1979): 36–38.

Hollister comments on the distinctly different approaches of youthful glassmakers William Carlson and Christopher Ries, which were on view in a two-person exhibition at the Contemporary Art Glass Group in New York City (806 Madison Avenue). A professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Carlson creates sculptural perfume bottles that evidence an affinity with art deco and an interest in the graphic qualities of glass color achieved through cutting and polishing blown pieces to reveal their refractive interiors. The highly prolific Ries, a recent MFA recipient, displays both lower-cost blown vessels and rarified carved sculptures in clear optic crystal. While commenting on the innovation in sculptural glass these works represent, Hollister identifies Ries’s cut crystal as “mostly too expensive and perhaps too abstract to be commercially successful.” Techniques discussed include glassblowing, Vitrolite inlay, sandblasting, and optical glass. Incl. prices and illus. (6 color) of work by William Carlson and Christopher Ries.

William Carlson, Contemporary Art Glass Group [later Heller Gallery], Michelangelo, Pablo Picasso, Christopher Ries, Steuben, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

“Seventh Annual Glass National at Habatat. Collectors Editions 7, no. 3 (Summer 1979): 29–31.

“Seventh Annual Glass National at Habatat. Collectors Editions 7, no. 3 (Summer 1979): 29–31.

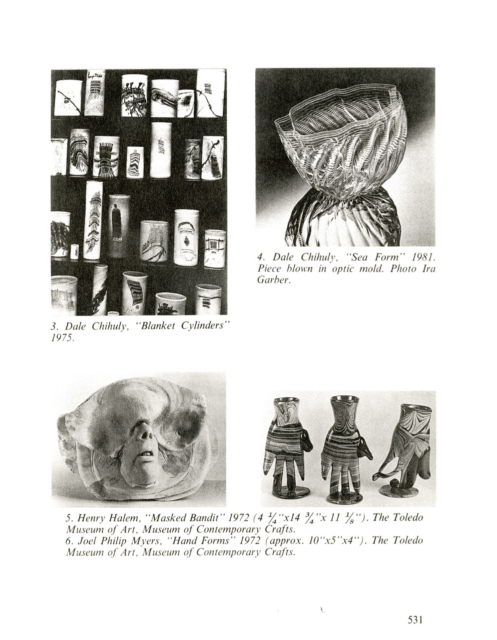

Frenzied buying accompanied the opening of the much-expanded 7th annual glass national at Habatat Galleries in Dearborn, Michigan (1820 N. Telegraph Road, March 17–April 7, 1979). More interested in surface ornament than form, most glassblowers submitted vessels, but the show was saved from becoming a “monotony of ovoid vases with vestigial necks” by the variety of shapes in the works of Michael Nourot, Dick Huss, George Thiewes, and others. Millefiori was used increasingly as a decorative technique. Hollister deems the sculptural glass better than last year, but “in too many sculptural attempts … chance takes the place of form and miscalculations are welcomed as if they were inspirations.” He finds the glass paintings of Henry Halem especially compelling. Incl. prices and illus. (3 b/w, 7 color) of work by John Bingham, Henry Halem, Dick Huss, Harvey Littleton, Joel Philip Myers, Michael Nourot, Richard Ritter, George Thiewes, Charles Wright, and Brent Young.

Herb Babcock, Robert Bartlett, John Bingham, Thomas Boone, John Byron, Habatat Galleries, Henry Halem, Ferdinand Hampson, Dick Huss, Joey Kirkpatrick?, Harvey Littleton, Flora Mace, Henri Matisse, Henry Moore, Deb Myers, Joel Philip Myers, Jon Myers, Michael Nourot, Art Reed, Richard Ritter, George Thiewes, Charles Wright, Brent Young

“Contemporary Paperweights, An International Exhibition at Habatat.” Collector Editions 7, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 40–41.

“Contemporary Paperweights, An International Exhibition at Habatat.” Collector Editions 7, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 40–41.

Hollister enthusiastically reviews the Michigan-based Habatat Galleries’ “gigantic” show, which features glass paperweights made by approximately 75 contemporary artists. While a few of the weights incorporate traditional nineteenth-century European techniques and designs, such as millefiori, the majority demonstrate a profound shift in aesthetic choices and approach as studio glass artists experiment with the paperweight form. The show reveals the paperweight as “a small convenient means to work out possibilities and fantasies, to consolidate and refine ideas applied to large glass containers and sculptural forms.” Hollister captures the breadth of reinvention through brief descriptions of several artists’ work, discussing how they manipulate color and layering in pursuit of realism, illusion, or abstraction and how they play with surface texture. The forms range from amorphous shapes to geometric and sliced solids with sculptural qualities to weights with multiple components. Incl. illus. (9 color) of work by Bob Bartlett, Steven Correia, Lee Hudin, Janet Kelman, Gerald Larcomb and Sally Wicht, Harvey Littleton, John Nickerson, Mark Peiser, and Pete Robison.

Rick Ayotte, Bob Banford, Bob Bartlett, Steven Correia, Habatat Galleries, David Huchthausen, Lee Hudin, Dick Huss, Charles Kaziun, Janet Kelman, Gerald Larcomb, Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton, Doug Merritt, Milropa Studios, Murano, John Nickerson, Orient and Flume, Mark Peiser, Roger Tory Peterson, Richard Ritter, Pete Robison, Vandermark Studios, Francis Whittemore, Sally Wicht, Joe Zimmerman

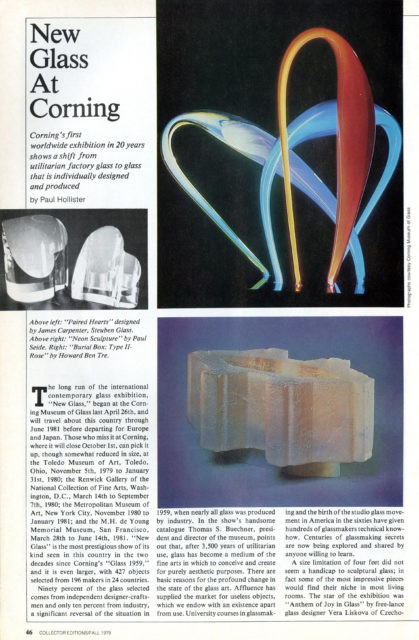

“New Glass at Corning.” Collector Editions 7, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 46–50.

“New Glass at Corning.” Collector Editions 7, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 46–50.

In 1979, 20 years after the pathbreaking exhibition Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass, The Corning Museum of Glass organized New Glass: A Worldwide Survey. While the earlier show catalogued the growth of modern design in industrially produced glass, New Glass heralded the international rise of the independent artist-craftsman. The show included 427 objects from 196 makers in 24 countries. This highly influential exhibition, which helped put studio glass on a national stage, traveled to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, and the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum after opening at Corning. In his lengthy review, Hollister pays particular attention to the show’s numerous sculptural works, of which there were almost none in 1959. He rates among New Glass’s most successful pieces Anthem of Joy in Glass by the Czech designer Věra Lišková, “the star of the exhibition … a fairytale blown by lampwork.” He also describes several memorable vessel forms; notes examples of whimsy, kitsch, and some “fine looking” commercial tableware; and suggests that the exhibition’s four-foot size limitation was at least partly responsible for the poor showing of stained and leaded glass. In the end, however, Hollister returns to the exhibition’s sculptural selections, remarking, “Now we know that glass can accommodate almost any aesthetic experience.” These works, like the exhibition catalogue’s cover illustration of Tom Patti’s Banded Bronze, show that glass “is on the way to something new.” Incl. illus. (8 b/w, 8 color) of work by Howard Ben Tré, Michael Boehm, James Carpenter, Gunnar Cyrén, Hans Godo Fräbel, Richard Glasner, J. R. Grossman, Pavel Hlava, Věra Lišková, Orrefors, Anthony Parker, Tom Patti, Peter Rath, Rosenthal Glas & Porzellan AG, Albin Schaedel, and Paul Seide. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Paul Hollister Self-recording, April 11, 1979 (Corning BIB ID: 168418).

Blanka Adensamová, Art Centrum, Hartmut Bechmann, Howard Ben Tré, Karl Berg, Michael Boehm, Thomas Buechner, James Carpenter, The Corning Museum of Glass, Gunnar Cyrén, Dan Dailey, Daum, David Dowler, Torres Esteban, Ulla Forsell, Hans Godo Fräbel, Richard Glasner, Gral-Glashütte GmbH, J.R. Grossman, Lars Hellsten, Pavel Hlava, David Huchthausen, Vladimír Jelínek, Adolf Stepanovich Kurilov, Dominick Labino, Věra Lišková, J&L Lobmeyr, René Magritte, Henri Matisse, Maria Meszaros, Metropolitan Museum of Art, M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, Jean-François Millet, Klaus Moje, Roberto Moretti, Bretislav Novák, Jr., Orrefors, Anthony Parker, Tom Patti, Pilgrim Glass, Oldřich Plíva, Peter Rath, Renwick Gallery, Rochester Folk Art Guild, Rosenthal Glas & Porzellan AG, Miluse Roubícková, Ivo Rozsypal, Fumio Sassa, Albin Schaedel, Helmut Schäffenacker, Franz Schubert, Livio Seguso, Paul Seide, Charles Sheeler, Smithsonian Institution, Vratislav Sotola, Steuben, Toledo Museum of Art, František Vízner, Steven Weinberg

“International Artists Exhibit Their Glass.” New York Times, November 8, 1979, C3. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EgSsV7

“International Artists Exhibit Their Glass.” New York Times, November 8, 1979, C3.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EgSsV7

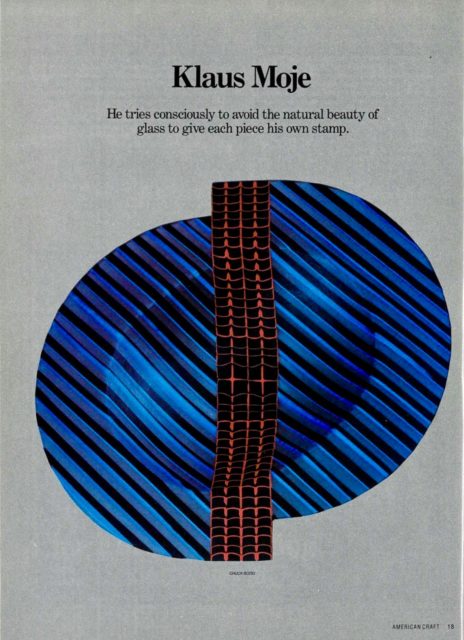

Hollister reviews Pilchuck Projects 79, the first exhibition at Gallery II (18 East 67th Street, New York), a new venture by the Contemporary Art Glass Group. The show features work made by Ann Wärff and Wilke Adolfsson of Sweden as well as Klaus and Isgard Moje of Germany during their residencies at Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington. Pilchuck’s Dale Chihuly also participates in the show. Warff, a Kosta Boda designer and Coburg Glass Prize winner, has worked with master gaffer Adolfsson to produce softly colored blown and acid-etched vessels depicting “the private imagery of [Wärff’s] Scandinavian farm.” Klaus Moje’s roughly ground fused-and-slumped glass bowls recall granite or marble and evince “an austere power.” Hollister remarks that Isgard Moje’s small, heavy vessels come off less well in the show, having “a vaguely dusty, dated look, like something found in the attic.” Chihuly’s “wilting, unstable, asymmetric and useless glass baskets” are saved from earlier cuteness by nesting smaller baskets inside to create “kinetic sculptural groupings.” Incl. prices and illus. (1 b/w) of work by Dale Chihuly.

Wilke Adolfsson, Dale Chihuly, Contemporary Art Glass Group [later Heller Gallery], Kosta Boda, Isgard Moje-Wohlgemuth, Klaus Moje, Pilchuck Glass School, Ann Wärff

“Studio Glass: The Next Decade.” Collector Editions 8, no. 1 (January 1980): 42–43.

“Studio Glass: The Next Decade.” Collector Editions 8, no. 1 (January 1980): 42–43.

Artist Harvey Littleton and seven gallery owners each comment on the state of studio glass in response to Hollister’s query about what to expect of the field in the 1980s. Littleton predicts that American glass artists will ultimately surpass their European peers in quality and technique, even in commercial production. Most of the dealers, however, focus on the difficulty posed by the very popularity or trendiness of studio glass—the challenge of finding and identifying exceptional pieces that truly qualify as “art,” as opposed to more commercially oriented or “craft” glass for the general buying public. Hollister concludes the article by observing that while terminology does not yet “distinguish between glass that is art and glass that is craft … it is ultimately the glass itself that reveals which it is” to the viewer. Incl. illus. (2 b/w, 3 color) of work by Dale Chihuly, Harvey Littleton, Joel Philip Myers, and Steven Weinberg. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Harvey K. Littleton Interview with Paul Hollister, November 7, 1979 (Corning BIB ID: 168575).

Thomas Boone, Dale Chihuly, Gallé, Ferdinand Hampson, Douglas Heller, Joanne Levi, Harvey Littleton, Joel Philip Myers, Linda Norton, Marilyn Schahet, Eric Sinizer, Tiffany, Steven Weinberg

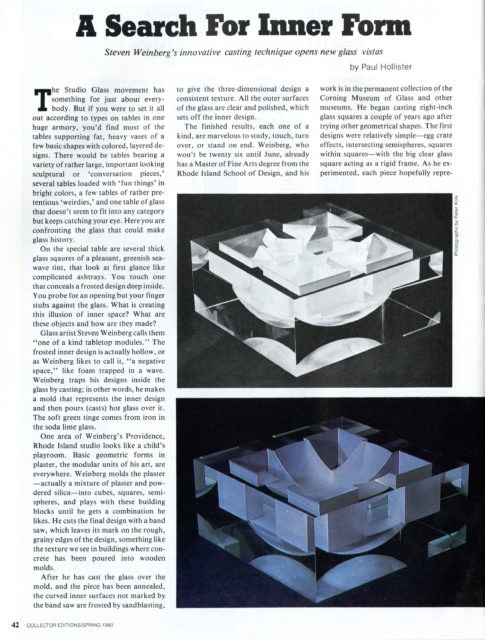

“A Search for Inner Form.” Collector Editions 8, no. 2 (Spring 1980): 42–43.

“A Search for Inner Form.” Collector Editions 8, no. 2 (Spring 1980): 42–43.

Artist Steven Weinberg, based in Providence, Rhode Island, uses casting techniques in distinctive new ways to encase geometric designs inside modular glass forms. The shortest of Hollister’s three profiles of the artist, this article describes Weinberg’s time-consuming method of casting hot glass over carefully grouped plaster-silica molds to produce negative spaces in blocks of translucent glass. He sandblasts additional texture and color into the interior forms and polishes the blocks’ exteriors, producing an effect “like foam trapped in a wave.” Weinberg’s work moves away from the simple, symmetrical shapes with which he began, becoming more complex and challenging. His “technically innovative” and “visually powerful” glass objects defy existing categories of glasswork and have the potential to “make glass history.” Incl. prices and illus. (1 b/w, 3 color) of work by Steven Weinberg.

Frederick Carder, Corning Glass Works [later Corning Incorporated], The Corning Museum of Glass, Lalique, Michelangelo, Rhode Island School of Design, Charles Smith, Steven Weinberg

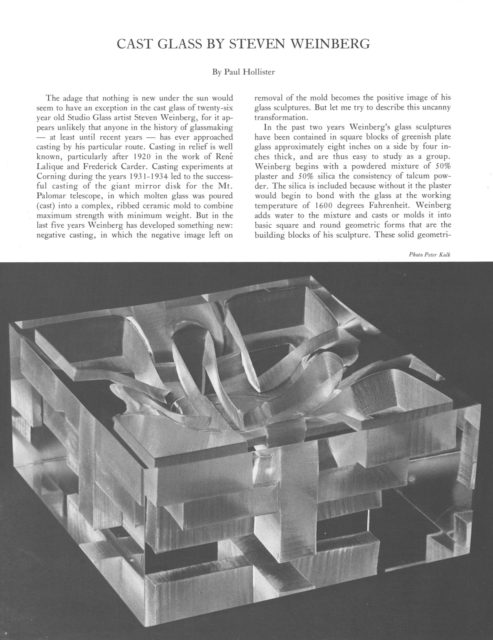

“Cast Glass by Steven Weinberg.” Glass Club Bulletin, no. 129 (Spring 1980): 5–8.

“Cast Glass by Steven Weinberg.” Glass Club Bulletin, no. 129 (Spring 1980): 5–8.

Hollister re-presents in a slightly different, longer form the same information conveyed in his Collector Editions (vol. 8, no. 2, Spring 1980) profile of Steven Weinberg. He emphasizes the uniqueness of Weinberg’s casting process, includes additional technical details, and engages more deeply with the changing aesthetics of his modular sculptures over the two previous years. Weinberg continues to vary and improvise within the formal restrictions of his chosen approach. If his earlier, simpler designs captured the tension between “three-dimensional form and its containment,” in his newer works “the interaction between negative and positive spaces became more interesting, more deceptive,” and more architectural, challenging and puzzling the viewer with “dangerous avenues” and mazelike blind alleys. Hollister characterizes Weinberg as “one of the most promising members” of the American studio glass movement. Incl. illus. (4 b/w) of work by Steven Weinberg.

Frederick Carder, Corning Glass Works [later Corning Incorporated], The Corning Museum of Glass, Lalique, Michelangelo, Rhode Island School of Design, Charles Smith, Steven Weinberg

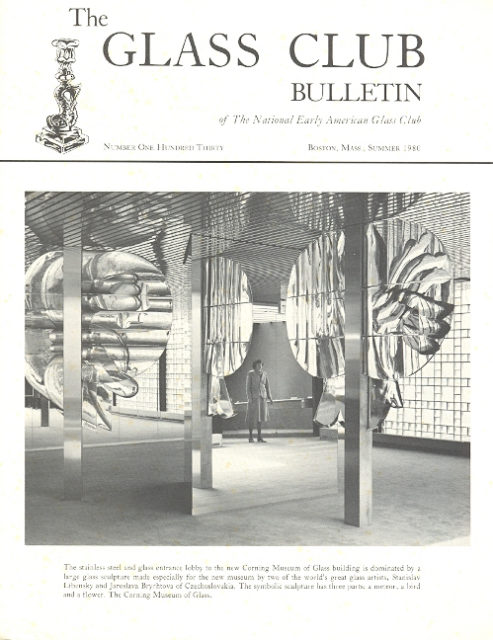

“The New Corning Museum of Glass, a Personal View.” Glass Club Bulletin, no. 30 (Summer 1980): 3–5.

“The New Corning Museum of Glass, a Personal View.” Glass Club Bulletin, no. 30 (Summer 1980): 3–5.

This account of The Corning Museum of Glass’s new building (opened June 1, 1980) is a longer and indeed more personal response to the museum’s renovation than the one Hollister later wrote for Collector Editions (vol. 8, no. 4, Fall 1980). While providing similar information about the new museum’s layout and exhibitions, this version adds extensive descriptions of the Gunnar Birkerts–designed building’s exterior, entry ramp, and lobby, as well as an exterior view of the building and an illuminating floor plan. Hollister also gives free rein to his enthusiasm for the reinstalled museum, from “the wonderful library” to “superbly confected” dioramas to the “knock-out collection” arranged in encyclopedic displays that are “exhilarating, breathtaking, and finally overwhelming.” While dismissing some design elements as shameless public-relations stunts and fearing that the new museum “is not, as touted, above flood level”—the devastating damage done to the original museum by Hurricane Agnes in 1972 having provided some of the impetus for renovation—Hollister nonetheless pronounces the new museum “a resounding success” and “a treasure house for civilization.” Incl. illus. (4 b/w) of work by Gunnar Birkerts, Jaroslava Brychtová, and Stanislav Libenský.

Gunnar Birkerts, Jaroslava Brychtová, The Corning Museum of Glass, Erwin Eisch, Paul Gardner, Rube Goldberg, Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton, Stanislav Libenský, Paul Seiz, Jerome Strauss, Tiffany

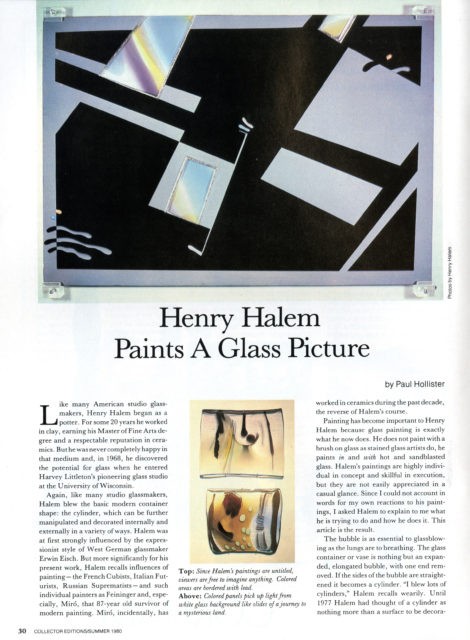

“Henry Halem Paints a Glass Picture.” Collector Editions 8, no. 3 (Summer 1980): 30–32.

“Henry Halem Paints a Glass Picture.” Collector Editions 8, no. 3 (Summer 1980): 30–32.

Following an early background in ceramics, Henry Halem studied glassblowing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with Harvey Littleton. After working traditionally with the material for several years, Halem developed a novel technique for producing flat glass panels in 1977. Enamored by these pieces in his review “Seventh Annual Glass National at Habatat” (Collector Editions 7, no. 3, 1979), Hollister traces Halem’s multistep process in this article. Beginning in the hot shop, Halem produces custom-colored sheet glass by first blowing cylinders and opening them into flat panels through a centuries-old technique. He uses the custom sheets in concert with industrially-made glass to create assemblages that are further enriched with sandblasting. Hollister notes that Halem has recently begun to use commercial glass alone to “liberate himself from the tyranny of the glassmaker’s bench.” Incl. prices and illus. (4 color) of work by Henry Halem.

Dale Chihuly, Erwin Eisch, Lyonel Feininger, Henry Halem, James Harmon, Paul Klee, Harvey Littleton, Flora Mace, Joan Miró, Mark Peiser, University of Wisconsin-Madison

“Hollister on Glass: CEQ’s Expert Reviews Glass Artistry.” Collector Editions 8, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 33–34.

“Hollister on Glass: CEQ’s Expert Reviews Glass Artistry.” Collector Editions 8, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 33–34.

Hollister discusses contemporary Scandinavian glass on view at Habatat Galleries (Lathrup Village, Michigan, June 14–July 14). Four designers for Sweden’s Orrefors employ decorative styles developed in the factory decades earlier; Hollister describes both the Graal technique of cutting a design into colored glass and then encasing it in clear glass, used by artists Gunnar Cyrén and Eva Englund, and the variant Ariel technique, used by Olle Alberius and Lars Hellsten, in which designs are sandblasted into a clear glass layer encasing colored glass and then enclosed again in clear glass. Hollister also discusses work by the independent designers and master-glassblower team of Ann Wärff and Wilke Adolfsson, including blown and etched vessels whose imagery exhibits “the creative drama we associate with painting” and “evocative” sculptural panels. Incl. prices and illus. (4 color) of work by Wilke Adolfsson, Eva Englund, Edla Freij, Hadeland Glassworks, Finn Lynggaard, Orrefors, and Ann Wärff.

Wilke Adolfsson, Olle Alberius, Monica Bäckström, The Corning Museum of Glass, Gunnar Cyrén, Eva Englund, Ulla Forsell, Edla Freij, Simon Gate, Habatat Galleries, Hadeland Glassworks, Edvard Hald, Lars Hellsten, Eric Höglund, Jan Johansson, Kosta Boda, Lalique, Vicke Lindstrand, Finn Lynggaard, Benny Motzfeldt, Orrefors, Steuben, Ten Arrow, Ann Wärff

“Hollister on Glass: Corning’s Glass Mecca.” Collector Editions 8, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 34.

“Hollister on Glass: Corning’s Glass Mecca.” Collector Editions 8, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 34.

The article sketches the layout and installation of The Corning Museum of Glass’s new building for its 20,000-piece collection, which opened to the public on June 1, 1980. This “world center” for glass exhibition and publication has a library at its core, around which the curving main gallery provides a chronological overview of glass history from 1500 BC to the present. Other spaces and displays permit in-depth engagement with glass from specific eras and cultures around the globe, and repeating films contextualize exhibited objects by “showing the various important historical techniques involved.” Hollister emphasizes how the installations facilitate learning about glass but notes that the museum design will suit even hurried visitors. Similar to but shorter than Hollister’s “The New Corning Museum of Glass, a Personal View” in The Glass Club Bulletin (no. 30, Summer 1980). Incl. illus. (2 b/w) of work by Georges Despret, Jaroslava Brychtová, and Stanislav Libenský.

Jaroslava Brychtová, Frederick Carder, The Corning Museum of Glass, Daum, Georges Despret, Gallé, Stanislav Libenský, Tiffany

“Some Recent Works By the Show’s Stars.” New York Times, November 20, 1980, C6. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EfF17I

“Some Recent Works By the Show’s Stars.” New York Times, November 20, 1980, C6.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EfF17I

Hollister briefly describes four exhibitions at the Heller Gallery in New York City. They include contemporary works in the Corning-organized New Glass exhibition, recently opened at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, plus solo shows spotlighting the two American studio glass innovators Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino and the Yugoslavian artist Raoul Goldoni. Littleton’s geometrically sliced glass canes “reveal interiors that suggest x-rays of flowers,” while Labino’s historical investigations—some of which are on loan from collectors—are so technically sound, “one can be assured that the glass will never crack from some internal stress.” Goldoni, accomplished in several media, shows ambitious glass and bronze “human skulls, animal heads, and abstract groupings that suggest the growth of living forms.” Incl. prices and illus. (1 b/w) of work by Tom Patti.

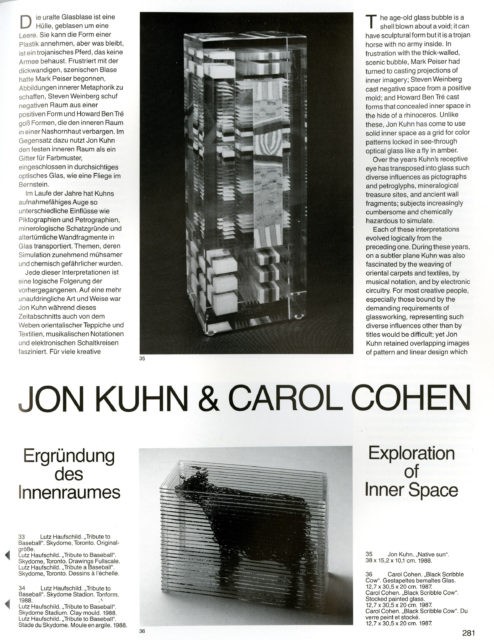

Raoul Goldoni, Dale Chihuly, The Corning Museum of Glass, Heller Gallery, Kosta Boda, Jon Kuhn, Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton, Richard Marquis, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Joel Philip Myers, Orrefors, Tom Patti, Steven Weinberg

Jump to 19811981

Americans in Glass. Wasau, WI: Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, 1981.

Americans in Glass. Wasau, WI: Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, 1981.

In 1981, the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wasau, Wisconsin, mounted Americans in Glass, the third of a triennial of exhibitions documenting the state of the field. Organized in consultation with artist David Huchthausen, the show highlights the work of 75 contemporary makers, selected by jurors Paul Hollister, artist Italo Scanga, and Peter Rath, co-owner of J&L Lobmeyr Glass. The 80-page catalogue contains Huchthausen’s introduction, the jurors’ statements, and a page for each artist featuring a large image of their work, a brief statement, and their CV. Hollister argues that a hybridization of art and technique “has produced the growing phenomenon we call studio glass.” Where the relative dearth of technical skills during the movement’s first decade (1962–72) resulted in objects that “ranged from the safe and salable to experimental,” artists’ rapid improvement in technical proficiency led to a veritable “menagerie of glass,” limited only by artistic imagination. The dizzying range of approaches and styles, and the swift pace of change, make it “difficult to establish practical criteria for judging,” hence the jurors sought “to reach unanimity on what was exhibitable beyond a reasonable doubt.” Hollister observes that the final selections “represent a broad spectrum of the potentials of glass.” Subsequent venues include the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York City and Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Incl. illus. (36 b/w, 39 color) of included artists’ work.

Hank Murta Adams, Valerie Arber, Tom Armbruster, Tina Aufiero, Dorothy Bauer, Larry Bell, Howard Ben Tré, Katherine Bernstein, Bonnie Biggs, Harry Boyer, Matthew Buechner, Ken Butterfield, William Carlson, James Carpenter, Sydney Cash, Bruce Chao, Thomas Chiconas, Dale Chihuly, Jon F. Clark, Richard Cohen, Cooper Hewitt Museum, The Corning Museum of Glass, Lynn Criswell, Dan Dailey, William Dexter, David Dowler, Stephen Dee Edwards, Thomas Fleming, Raoul Goldoni, Pam Haight, Henry Halem, James Harmon, David Hasslinger, W. Stephen Hodder, Eric Hopkins, Paul Housberg, David Huchthausen, Margie Jervis, Robert Kehlmann, David Kerner, Joey Kirkpatrick, Alan Klein, Bruce Kleist, Mark Kobasz, Krannert Art Museum, Susie Krasnican, Jon Kuhn, Dominick Labino, David Leppla, Marvin Lipofsky, Harvey Littleton, J&L Lobmeyr, Flora Mace, Linda MacNeil, Andrew Magdanz, Richard Marquis, Andy McGivern, George Menzelos, Janis Miltenberger, Peter Mollica, Benjamin Moore, Joel Philip Myers, Douglas Navarra, Tom Patti, Flo Perkins, Richard Posner, Narcissus Quagliata, Rahr-West Museum, Paul Rath, Christine Robbins, Ginny Ruffner, Italo Scanga, David Schwarz, Eric Sealine, Paul Seide, Mary Shaffer, Robert Shank, Susan Stinsmuehlen[-Amend], Molly Stone, Marcia Theel, Toledo Museum of Art, University of California San Diego, David Van Arsdale, Jane Wagned, David Wagner, James Watkins, Jack Wax, Steven Weinberg, Hamilton Wendt, Western Association of Art Museums, Mary White, Christopher Wilmarth, Sali Wohlbach, Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, Brent Young, Toots Zynsky

“Chihuly Glass Show Features Sea Forms.” New York Times, April 2, 1981, C8. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2Eega4i

“Chihuly Glass Show Features Sea Forms.” New York Times, April 2, 1981, C8.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2Eega4i

Forms that “are only memories of the sea” by Dale Chihuly are on view at the Charles Cowles Gallery in the artist’s first New York solo show. In a color palette of pinks, corals, pearly grays, and off-whites, which contrasts with that of other glassblowers, Chihuly’s sea forms reflect the contest between form and gravity that is the essence of glassblowing. Hollister notes the spread of Chihuly’s influence as a founder of Pilchuck Glass School and chairman of the glass and sculpture departments of the Rhode Island School of Design. Incl. illus. (1 b/w) of work by Dale Chihuly.

Charles Cowles Gallery, Dale Chihuly, Pilchuck Glass School, Rhode Island School of Design

“Contemporary Art Glass Gallery and Heller Gallery.” American Craft 41, no. 2 (April/May 1981): 20–23.

“Contemporary Art Glass Gallery and Heller Gallery.” American Craft 41, no. 2 (April/May 1981): 20–23.

A profile of Douglas Heller outlining the development of his galleries (“generally recognized as the first devoted exclusively to contemporary art glass”) and his developing approach to collecting, this article investigates the profound growth of the studio glass movement in the United States from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Encouraged by art nouveau glass dealers Minna and Arthur Rosenblatt, Heller and the Rosenblatt’s son, Joshua, began representing a handful of studio glassmakers at antique fairs before opening their first gallery on Manhattan’s tony Upper East Side in the early 1970s. As the field matured, the pair experimented with new venues and novel exhibition strategies, adjusting their business name accordingly. By 1978, Heller and his brother Michael became the gallery’s sole proprietors, changing the name to Heller Gallery. Their two-floor venue showcases the work of 100 artists and boasts an international clientele. Incl. illus. (5 color) of work by Sydney Cash, Raoul Goldoni, and John Nygren.

Sydney Cash, The Corning Museum of Glass, Robin Drake, Gallé, Raoul Goldoni, Lisa Hammel, Annie Heller, Douglas Heller, Michael Heller, Heller Gallery, Diane Itter, Roland Jahn, Hy Klebanow, John Lundberg, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, John Nygren, Tom Patti, Mark Peiser, Penland School of Crafts, Pilchuck School of Glass, Arthur Rosenblatt, Joshua Rosenblatt, Minna Rosenblatt, Tiffany, Toledo Museum of Art

“Contrast in Styles at Glass Gallery.” New York Times, July 2, 1981, C7. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V5pSvn

“Contrast in Styles at Glass Gallery.” New York Times, July 2, 1981, C7.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V5pSvn

Hollister discusses how the multiculturally referent blown-glass heads in Don Shepherd’s Helmeted Warrior series contrast with Meredith Wenzel’s subtly colored, delicately patterned vases in a two-person show at Heller Gallery in New York that emphasizes the breadth of contemporary studio glass. Shepherd’s Helmeted Warriors combine blown glass and steel wire to create communicative pieces with “pleading eyes and mouths,” while the efficacy of the recycled glass “failures” in his Transitional Heads series remains to be seen. Wenzel’s highly individualized style, a personal take on a cutting-and-casing blowing technique popularized by her teacher Tom McGlauchlin, produces works that deserve to be “treasured” despite occasional technical flaws. Incl. prices.

Alexander Calder, Heller Gallery, Gustav Klimt, Tom McGlauchlin, Don Shepherd, Meredith Wenzel

“Steven Weinbergs Giesstechnik / Steven Weinberg’s Casting Technique: Something New Under the Sun.” Neues Glas, no. 4 (1981): 143–47.

“Steven Weinbergs Giesstechnik / Steven Weinberg’s Casting Technique: Something New Under the Sun.” Neues Glas, no. 4 (1981): 143–47.

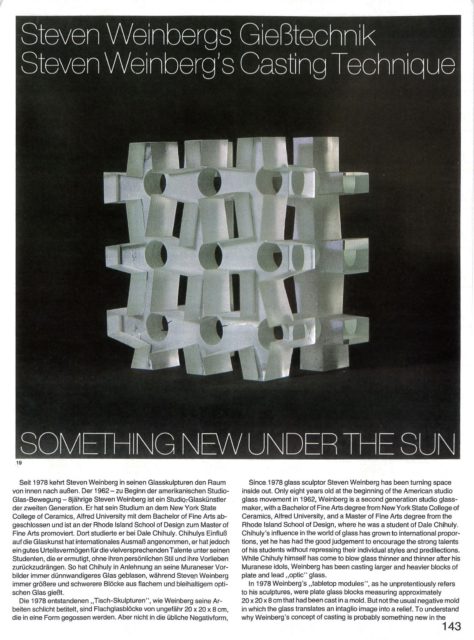

Hollister combines information from his two previously published profiles of Steven Weinberg (Collector Editions 8, no. 2 [Spring 1980]; and Glass Club Bulletin, no. 129 [Spring 1980]) to give a detailed account of the artist’s unusual and lengthy process for making modular glass forms by casting glass over plaster molds and then sandblasting, grinding, and polishing it. He describes Weinberg as a second-generation studio glassmaker and notes that he was a student of Dale Chihuly at the Rhode Island School of Design. Hollister briefly summarizes the development of Weinberg’s work between 1978 and 1980 before discussing his current practice in 1981. While retaining his signature play of positive and negative spaces and of polished and sandblasted surfaces, the artist’s latest pieces have doubled in size and exchanged the trapped interiors that first caught Hollister’s attention for airy glass skeletons. He reserves judgment on Weinberg’s new direction, noting only that “it will be interesting how we come to see these pieces when we understand them more fully.” Incl. illus. (3 b/w, 3 color) of work by Steven Weinberg. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Steven Weinberg Interview with Paul Hollister, January 13, 1981 (Corning BIB ID: 168607).

Dale Chihuly, Buckminster Fuller, Michelangelo, Rhode Island School of Design, Steven Weinberg

“Theater in Glass.” American Craft 41, no. 5 (October/November 1981): 26–29. Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/16311/rec/218 American Craft Council, Digital File Vol41No05_Oct1981

“Theater in Glass.” American Craft 41, no. 5 (October/November 1981): 26–29.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/16311/rec/218

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol41No05_Oct1981

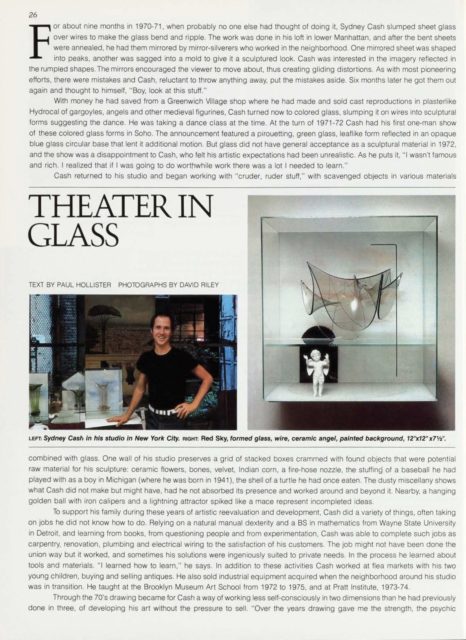

New York artist Sydney Cash first developed his novel technique for slumping “sheet glass over wires to make the glass bend and ripple” in 1970 and 1971, but it was not until the late 1970s that he perfected it. The results of his efforts were on view in the artist’s third solo show at the Heller Gallery in SoHo (October 3–31, 1981). On the thoughtfully composed and dramatically presented exhibition, Hollister comments, “No other glass comes to mind in which we see the interaction between melting glass and gravity so gracefully caught in the act of perpetuity.” Incl. illus. (7 color) of work by Sydney Cash. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Sydney Cash Interview with Paul Hollister, July 2, 1981 (Corning BIB ID: 168605).

Sydney Cash, Douglas Heller, Heller Gallery

“Swedish Glassware Shines in Historical Exhibition.” New York Times, November 5, 1981, C7. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2n9jLHr

“Swedish Glassware Shines in Historical Exhibition.” New York Times, November 5, 1981, C7.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2n9jLHr

Hollister describes the three-part show of 50+ pieces documenting the history of Swedish Orrefors glassware at the Heller Gallery of Glass Art in New York. Section one comprises the first American solo show for leading Orrefors designer Gunnar Cyrén. The second consists of a historical selection curated by Cyrén featuring “30 examples of Orrefors glass made since 1918” including three engraved pieces shown at the Paris international exposition in 1925. The third features “six important vessels” by the Orrefors innovators Edvard Hall and Simon Gate, on loan from well-known dealer Lillian Nassau. While Cyrén’s and Nassau’s contributions are for sale, the historical component curated by Cyrén is not. As a result, Orrefors has agreed “to copy any pieces that it contributed to the display.” The exhibition traveled through 1983. Incl. prices.

Gunnar Cyrén, Eva Englund, Simon Gate, Edvard Hald, Heller Gallery, Vicke Lindstrand, Nils Landberg, Ingeborg Lundin, Henri Matisse, Lillian Nassau, Edvin Ohrstrom, Orrefors, Sven Palmquist

“Studio Glass Artist to Exhibit in SoHo.” New York Times, January 7, 1982, C11. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeV064

“Studio Glass Artist to Exhibit in SoHo.” New York Times, January 7, 1982, C11.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeV064

Instrumental in developing “what is now called the studio glass movement,” Harvey Littleton “has also produced a diverse selection of his own glass.” Thirty pieces of Littleton’s work, which document his “search for form and the urge to produce,” were displayed at Exhibition Space in SoHo (112 Greene Street) in a show organized by the Heller Gallery. Many of Littleton’s forms begin with a process rooted in the centuries-old technique of millefiori glass cane, in which opaque glasses are gathered atop one another to produce a pattern when cut in cross-section. Littleton, by contrast, layers veils of transparent colors that he “twists, overlaps, and bisects … with a diamond saw, slicing them into segments that can be rearranged to suit.” The exhibition also includes earlier works on loan from collectors, including Do Not Spindle, “in which thick plates of glass are being lanced by metal, to which they respond by bending gracefully.”

Heller Gallery, Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton

“Glass Art Society 12th Annual Conference, New York City.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 105–6.

“Glass Art Society 12th Annual Conference, New York City.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 105–6.

Approximately 500 mostly young glassworkers and enthusiasts gathered for a “seemingly unending series of hour-long panel discussions” along with slide presentations and films at the 12th annual Glass Art Society conference in New York City, April 7–10, 1982. Hollister cheekily describes how lofty discussions on the nature of art and the future of glass reverted to “the much trampled ground of Art versus craft—craft being considered as a sort of blue collar Art.” He filled in for critic Clement Greenberg, who was not able to attend, and offered a conciliation in the form of a Robert Frost poem for the vaunted “what is Art” question. Incl. illus. (3 b/w) of Erwin Eisch, Frances Higgins, and Michael Higgins.

Dan Dailey, Erwin Eisch, Robert Frost, Henry Geldzahler, Clement Greenberg, Frances Higgins, Michael Higgins, Penelope Hunter-Stiebel, Richard Shiff

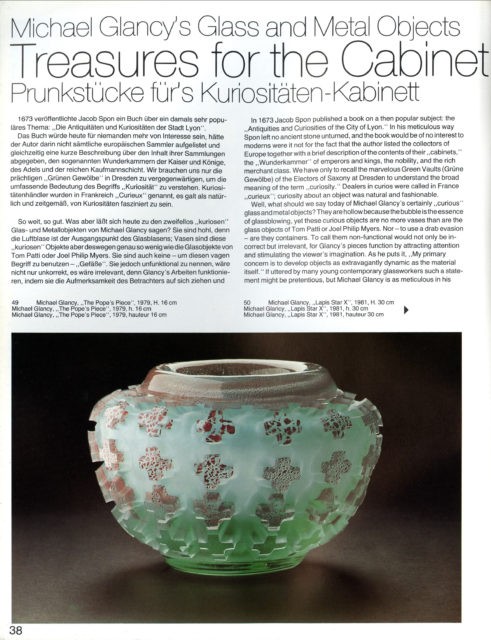

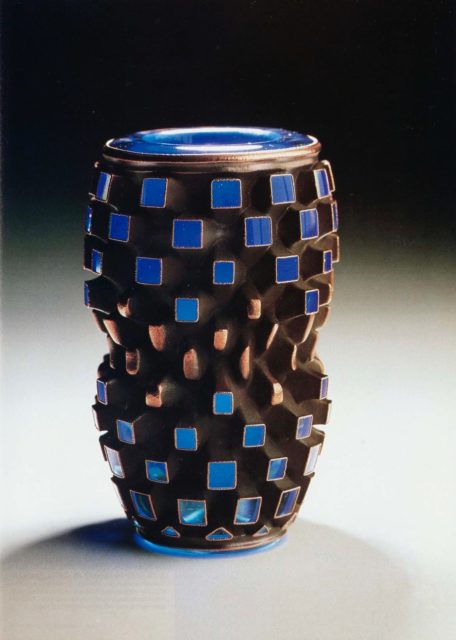

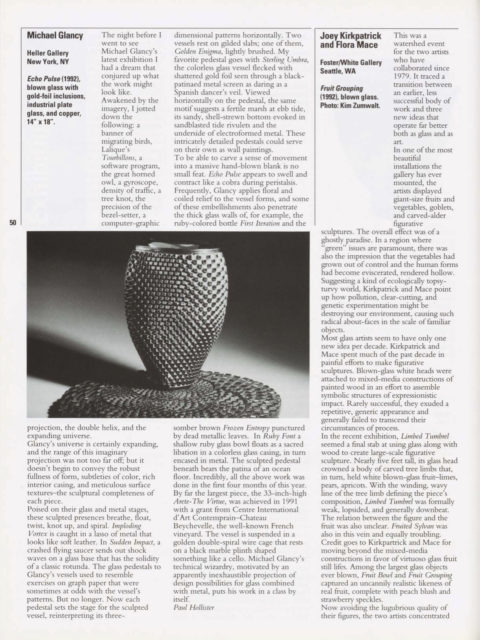

“Michael Glancy’s Glass and Metal Objects: Prunkstücke fürs Kuriositäten-Kabinett / Treasures for the Cabinet of Curiosities.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1982): 38–44.

“Michael Glancy’s Glass and Metal Objects: Prunkstücke fürs Kuriositäten-Kabinett / Treasures for the Cabinet of Curiosities.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1982): 38–44.

As in his profile of Michael Glancy published in American Craft (vol. 42, no. 4, August/September 1982), Hollister summarizes the artist’s formal training in ceramics, glass, and metalwork and carefully outlines the techniques at the heart of his work. Hollister describes the combination of glassblowing, sketching, stencil making, sandblasting, polishing, and electroforming processes through which Glancy creates his “jeweled objects” of glass and metal. Yet this article is less critical than the first, containing nearly twice the number of illustrations but lacking the detailed written descriptions of specific pieces and occasional skepticism. Incl. illus. (2 b/w, 5 color) of work by Michael Glancy.

Dale Chihuly, Daum, Michael Glancy, Maurice Marinot, Louis Mueller, Joel Philip Myers, Rodney Nakamoto, Tom Patti, Jacob Spon, Tiffany

“Howard Ben Tré’s Sculptures in Glass.” New York Times, April 1, 1982, C11. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EegX5g

“Howard Ben Tré’s Sculptures in Glass.” New York Times, April 1, 1982, C11.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EegX5g

Hollister reviews the four massive cast-glass columns by Howard Ben Tré at Hadler Rodriguez Gallery in Manhattan (38 East 57th Street, through April 15). Hollister situates the artist’s work as exemplifying a newly defined sculptural approach to glass. He observes that Ben Tré is critical of the seductiveness of glass and feels that artists should impose “their personalities on the medium.” Ben Tré pursues that individualized approach through an elaborate hot-casting process combining resin-bonded sand and sheet copper to produce unusual textures and tints of a variety of colors. He later augments the surfaces of his glassworks, which are cast at the Blenko Glass Company in Milton, West Virginia, with copper patina.

Howard Ben Tré, Blenko Glass Company, Hadler Rodriguez Gallery

“Light Affecting Form in Space: Glas von William Carlson / William Carlson’s Glasswork.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 84–88.

“Light Affecting Form in Space: Glas von William Carlson / William Carlson’s Glasswork.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 84–88.

This feature article traces the development of William Carlson’s work between 1976 and 1982. The artist’s early pieces, like the small perfume bottle that first drew Hollister’s attention, involved blown vessels faceted to reveal their interiors. Carlson further experimented with attaching flat pieces of Vitrolite—a colored structural glass—to his sliced vessels. He casted and laminated flat-sided containers with millefiori cores, foregrounding the interplay of color, reflection, and optical illusion. Hollister assesses this work as “a tremendous advance for Carlson” toward making fully three-dimensional sculpture. He carefully describes how Carlson laminates cast-glass shapes into larger compositions and then reduces them by cutting and grinding the result into a final form. These newest pieces maintain Carlson’s initial interest in layers, facets, angles, and reflection, but now they “are truly sculptural”: “The viewer can never look at the piece from one point and see what it is all about.” Incl. illus. (3 b/w, 3 color) of work by William Carlson.

Blenko Glass Company, William Carlson, Don Shepherd

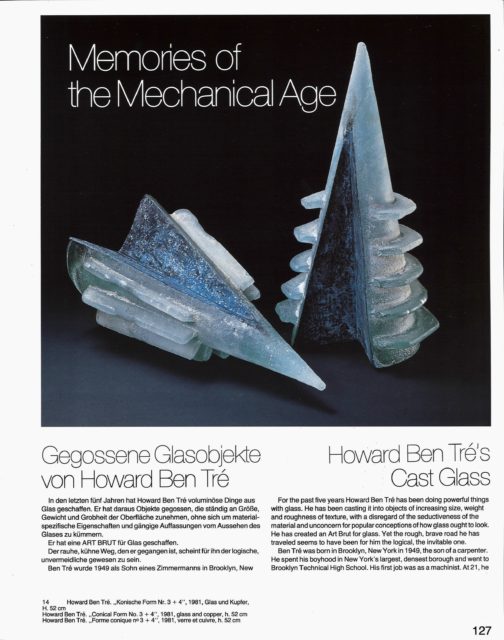

“Memories of the Mechanical Age: Gegossene Glasobjekte von Howard Ben Tré / Howard Ben Tré’s Cast Glass.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (1982): 127–33.

“Memories of the Mechanical Age: Gegossene Glasobjekte von Howard Ben Tré / Howard Ben Tré’s Cast Glass.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (1982): 127–33.

Howard Ben Tré grew up in the dense urban environment of Brooklyn, New York, attended Brooklyn Technical High School, and worked as a machinist before earning an MFA in sculpture and glass from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1980. Hollister relates this background to Ben Tré’s artistic development from 1978 to 1982, discussing how his use of copper in glass casting, mechanically evocative geometric forms, and practice of labeling rather than titling individual pieces lend his work both “industrial” and sculptural qualities. He details the artist’s process, from creating molds using wood or chemically bonded sand—into which he cast up to 500 pounds of glass in furnaces at RISD or, more recently, the Blenko Glass Company in Milton, West Virginia—to his treatment of accidental cracking and final surface texture. At Blenko, Ben Tré increased the scale of his work, a move that Hollister deems not entirely successful. Where he had given the artist’s recent exhibition of four large glass columns a fairly positive review in the New York Times (April 1, 1982), here he dismisses three of the four pieces as having “pound for pound … more weight than message.” Notwithstanding, he praises Ben Tré for having “the courage to ignore” the higher profit potential of smaller work. As noted by Neues Glas editors in the publication’s next issue (no. 4, 1982), Ben Tré took exception to Hollister’s criticism and pointed to art critic Kenneth Baker’s more positive review. Neues Glas reprinted Ben Tré’s letter and an excerpt from Baker’s review and asked readers to decide. Incl. illus. (4 b/w, 5 color) of work by Howard Ben Tré.

Howard Ben Tré, Blenko Glass Company, Charlie Chaplin, Dale Chihuly, The Corning Museum of Glass, Michael Glancy, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Rhode Island School of Design

“Glassblower Forges Delicate Sea Forms.” New York Times, June 3, 1982, C11. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeWVHy

“Glassblower Forges Delicate Sea Forms.” New York Times, June 3, 1982, C11.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeWVHy

Dale Chihuly’s second exhibition at the Charles Cowles Gallery (420 West Broadway, New York, June 5–26, 1982) features his Macchia series, which derives its name from the Italian word for speckled. Rather than the “gossamer delicacy” of the sea forms in his earlier Cowles show, the abstract Macchia pieces loosely reference “black mud, wet sand, and the cold machinery of waves.” Hollister describes the blowing process and notes Chihuly’s use of a glassblowing team.

Charles Cowles Gallery, Dale Chihuly

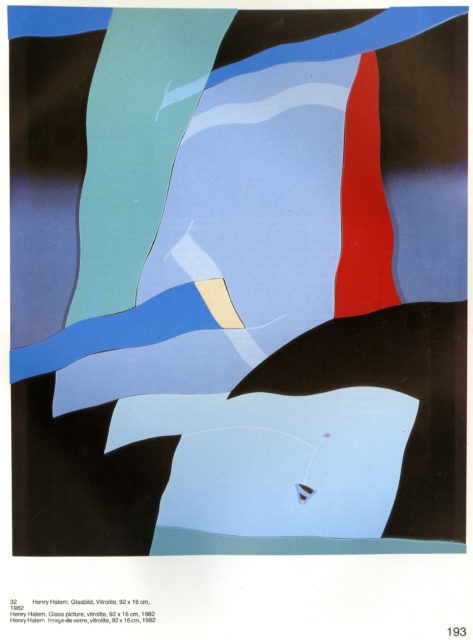

“Henry Halem: Die Fläche ist die Botschaft / The Plane Is the Message.” Neues Glas, no. 4 (1982): 189–94.

“Henry Halem: Die Fläche ist die Botschaft / The Plane Is the Message.” Neues Glas, no. 4 (1982): 189–94.

This article recapitulates and updates Hollister’s earlier profile of Henry Halem (Collector Editions 8, no. 3 [Summer 1980]). Hollister adds more detail to the early progression of Halem’s technique for making “paintings” in flat glass and discusses the artist’s thorough embrace of Vitrolite, an obsolete commercial building glass once readily available in a variety of vivid opaque colors and now sought and stockpiled by Halem and other artists. After discovering Vitrolite in 1979, Halem began sandblasting stenciled designs into subtle monochrome pieces; his latest work returns to his initial interest in color, collaging and inlaying different hues of Vitrolite into flat, abstract panels whose “bright, saturated colors push, loom, tear and slice through the field of vision.” For Halem, glass has become simply the medium in which he makes his art; the material itself “is unimportant.” Halem, professor of art and director of Kent State University’s glass program in Kent, Ohio, like other academics, faces the challenge of balancing his studio time with teaching responsibilities. Incl. illus. (3 b/w, 2 color) of work by Henry Halem.

Milton Avery, Joyce Cary, Arthur Dove, Lyonel Feininger, Henry Halem, Kent State University, Dominick Labino, Joan Miró, Rhode Island School of Design

“The Matrix Transformed.” American Craft 42, no. 4 (August/September 1982): 24–27. Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/16745/rec/223 American Craft Council, Digital File Vol42No04_Aug1982

“The Matrix Transformed.” American Craft 42, no. 4 (August/September 1982): 24–27.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/16745/rec/223

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol42No04_Aug1982

In his most recent works, Rehoboth, Maryland–based artist Michael Glancy has developed his distinctive sand-carved and electroformed vessels beyond the “geometrically decorative” into the realm of sculpture by addressing his techniques to the overall form of his pieces rather than just their surfaces. Introduced to electroforming while an MFA candidate in glass at the Rhode Island School of Design, Glancy has developed this technique, which uses electrical current to deposit copper onto a specially prepared substrate and is typically associated with metalworking, into a signature of his blown-vessel-and-plate constructions. Hollister gives a step-by-step account of the artist’s complicated processes and describes several pieces from the past four years. Skeptical of Glancy’s historical awareness and ambivalent about the carved plates that he uses to set off his vessels, Hollister is nonetheless positive about the artist’s work as a whole. Incl. illus. (5 color) of work by Michael Glancy.

Daum, Michael Glancy, Maurice Marinot, Louis Mueller, Rodney Nakamoto, Penland School of Crafts [later Penland School of Craft], Pilchuck School of Glass, Rhode Island School of Design, Tiffany

“Canadian Glass Comes to Maturity.” Ontario Craft 7, no. 3 (Fall 1982): 22–24.

“Canadian Glass Comes to Maturity.” Ontario Craft 7, no. 3 (Fall 1982): 22–24.

The high quality and prodigious talent of artists in the nascent Canadian studio glass movement was on view in two exhibitions coinciding with the 3rd annual Canadian Glass conference in Toronto. A student exhibition at Harbourfront demonstrated a “variety of ideas and obvious expertise” with “a kind of young daring that was largely lacking in the more secure efforts” that were on view in the Canadian Contemporary Glass 1982 show at the Koffler Gallery in Toronto. Artists self-selected the 150 pieces on view at the Koffler, many of which deployed glass techniques generically, making it seem “like seeing a replay” of American studio glass. Nonetheless, there were several highly accomplished works including those by Robin Fineberg, Francois Houdé, Toan Klein, Max Leser, and Ed Roman. Incl. illus. (3) of work by Robin Fineberg, Max Leser, and Karl Schantz.

Norman Faulkner, Christian Ferry, Robin Fineberg, Clark Geuttel, Robert Held, Greg Herman, Francois Houdé, Toan Klein, Koffler Gallery, Max Leser, Mark Peiser, Ed Roman, Karl Schantz, Loris Williams

“A Mixed Bag of Studio Glass Shows.” New York Times, October 7, 1982, C5. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2UYlTR2

“A Mixed Bag of Studio Glass Shows.” New York Times, October 7, 1982, C5.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2UYlTR2

Hollister discusses three Upper East Side galleries that exhibited glasswork, Departure Gallery, Theo Portnoy Gallery, and Heller Gallery of Glass Art. At Departure, he finds Vernon Brejcha’s blown works most compelling in an uneven show that also includes Katherine Bernstein’s figurative kiln-cast sculptures and Paul Marioni’s “tenuous portraits of what may be West Coast Indians” presented in a “rolled-like-dough cathedral glass process.” A solo show at Theo Portnoy by Toots Zynsky, recent recipient of an emerging arts grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, displays early versions of what would become her signature filet-du-verre process. On view at Heller are Michael Glancy’s “meticulously carved and electroplated vessels,” which have a “jewel-like richness,” and William Morris’s Eleven Standing Stones, based on the ancient stones of the Orkney Islands (UK) and displayed with their oversized wood molds constructed by woodworker Jon Ormbrek.

Katherine Bernstein, Vernon Brejcha, Departure Gallery, Michael Glancy, Heller Gallery, Paul Marioni, William Morris, Jon Ormbrek, Theo Portnoy Gallery, Toots Zynsky

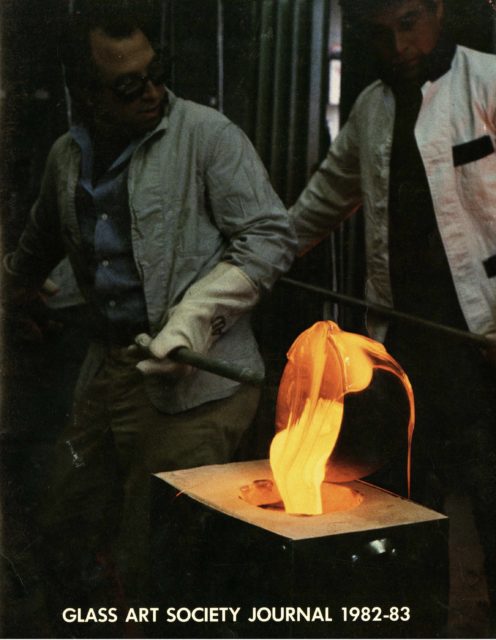

“What Makes Art?” With Henry Geldzahler, Richard Shiff, and Thomas Buechner. Glass Art Society Journal (1982): 5–11.

“What Makes Art?” With Henry Geldzahler, Richard Shiff, and Thomas Buechner. Glass Art Society Journal (1982): 5–11.

The journal published a transcript of the panel discussion at the Glass Art Society’s 12th annual conference in New York City, April 7–10, 1982, in which Hollister participated. (Hollister’s irreverent account of the conference proceedings appears in Neues Glas, no. 2 [1982].) As a last-second substitute for the art critic Clement Greenberg, Hollister had no time to prepare his thoughts on the topic of “What Makes Art?”; his brief opening comments respond to opinions offered by fellow panelists Richard Shiff, professor of art history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; New York City Commissioner of Cultural Affairs Henry Geldzahler; and panel moderator Thomas Buechner, founding director of The Corning Museum of Glass. The wide-ranging discussion, which included questions from the audience, touches on criteria for identifying “good” and “great” works of art; the distinctions (or lack thereof) between craft and fine art, between technique and idea, and between craftsman and designer; and ways in which producers and consumers alike play roles in “making” art. In his comments, Hollister often insists on the importance of process and skill in creating art objects; countering Schiff’s distinction between fine art and craft by redefining “craft” as “the skill with which art can be produced,” Hollister proposes that haptic or embodied knowledge contributes in unique ways to finished work. He also warns that Geldzahler’s injunction (with Ezra Pound) that artists should “make it new” too often leads to poor work in a crowded exhibition calendar, “which does not give the person a chance to develop.” He also disagrees with Geldzahler’s stipulation (à la Greenberg) that good art must be memorable. Buechner’s remarks on “stature” prompt Hollister to lament some glass artists’ tendency to think that bigger is better when it comes to scale. When audience member Susan Stinsmuehlen asks the panelists to identify examples of “good contemporary glass art,” all but Buechner decline to mention active artists by name; Hollister explains that he does not collect glass because even if he could afford it, it would pose a conflict of interest with his work as a critic. Incl. illus. (4 b/w) of work by Thomas Buechner, David Hockney, Paul Hollister, and Richard Shiff.

Peter Aldridge, George Balanchine, Dominick Biemann, Bjorn Borg, Thomas Buechner, Samuel Butler, Frederick Carder, Paul Cézanne, Dale Chihuly, The Corning Museum of Glass, Daum, Edgar Degas, Lowell Dickens, Erwin Eisch, Lydia Field Emmet, Robert Frost, Gallé, Henry Geldzahler, Clement Greenberg, Ralph Hardy, Eric Hilton, David Hockney, Hans Hofmann, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Paul Jenkins, Margaret Keane, Walter Keane, Ed Koch, Willem de Kooning, Lalique, Marvin Lipofsky, Harvey Littleton, Maurice Marinot, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Napoleon, Henri Navarre, LeRoy Neiman, Orrefors, Sven Palmquist, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Ezra Pound, Rembrandt, John Singer Sargent, Richard Shiff, Steuben, Susan Stinsmuehlen[-Amend], John Tenison, Tiffany, Diego Velasquez, Venini, Giuseppe Verdi, Johannes Vermeer, Richard Wagner, Andy Warhol, William Warmus, Tom Wesselmann, Sam Wiener

“3 New Exhibitions in Glass and Clay.” New York Times, January 27, 1983, C9. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeAy5g

“3 New Exhibitions in Glass and Clay.” New York Times, January 27, 1983, C9.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeAy5g

Three shows on view at the American Craft Museum display disparate approaches, timelines, and geographies to glass and ceramic production. Glen Lukens: Pioneer of the Vessel Aesthetic, organized by the Fine Arts Gallery of California State University, includes 26 pieces, likely from the 1920s and 1930s, demonstrating this American artist’s investigations into clay bodies, glazes, and unusual application methods. Czechoslovakian Glass: Seven Masters, guest curated by Meda Mladek, presents pieces drawing upon a variety of glasswork techniques, including engraving, cutting, and blowing, by Václav Cigler, Vladimir Kopecký, Jiří Harcuba, Stanislav Libenský, Jaroslava Brychtová, René Roubíček, and Věra Lišková. The third exhibition, The Vessel Form: Selections From the Permanent Collection, features ceramics from the last 50 years.

American Craft Museum [formerly Museum of Contemporary Crafts, later Museum of Arts and Design], Dominick Biemann, Jaroslava Brychtová, Václav Cigler, Albrecht Dürer, Mahatma Gandhi, Jiří Harcuba, Vladimir Kopecký, Stanislav Libenský, Věra Lišková, Elaine Levin, Glen Lukens, Meda Mladek, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Gertrud Natzler, Otto Natzler, Henry Varnum Poor, René Roubíček

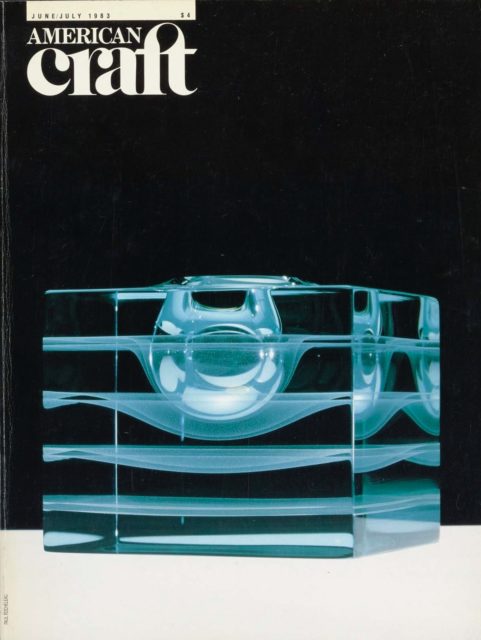

“Monumentality in Miniature.” American Craft 43, no. 3 (June/July 1983): 14–17, 88. Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/12923/rec/228 American Craft Council, Digital File Vol43No03_Jun1983

“Monumentality in Miniature.” American Craft 43, no. 3 (June/July 1983): 14–17, 88.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/12923/rec/228

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol43No03_Jun1983

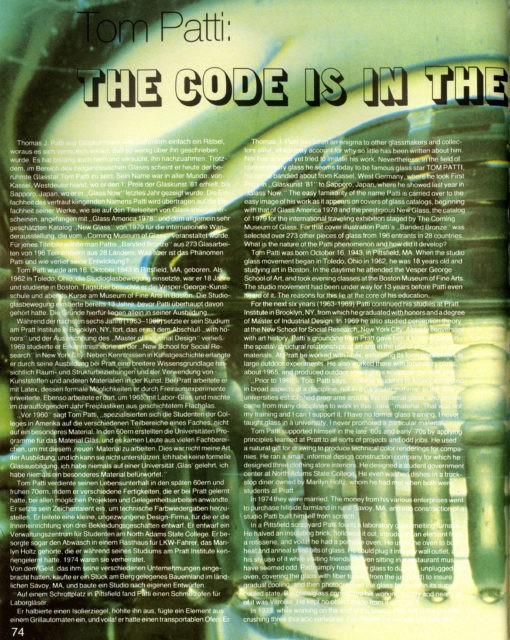

Hollister recounts and assesses artist Tom Patti’s highly individualized approach to glassmaking. Trained in industrial design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, and perception theory at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan, Patti came to glassmaking 12 years after the Toledo Glass Workshops kicked off the studio glass movement in 1962. Rather than begin with molten material, Patti inflates heated plate glass and Vitrolite reclaimed from building exteriors in a process he terms “blown-laminated glass.” The resulting pieces are diminutive in size but architectonic in feel. Hollister categorizes Patti’s work in three phases: inflating a laminated cube into a sphere (1975–77), supporting and occasionally obscuring a small bubble “within a framework of wings and fins” (1977–79), and extending “these vertical or horizontal extensions or ribs” on two of the four sides to create illusionistic, architectural spaces (from 1980). Incl. illus. (3 color) of work by Tom Patti. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Tom Patti Interview with Paul Hollister, March 4, 1983 (Corning BIB ID: 168377).

The Corning Museum of Glass, Douglas Heller, Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marilyn Holtz Patti, Sienna Rose Patti, Tom Patti, Pratt Institute, Kenneth Wilson

“Three Generations of Glass Designers.” New York Times, April 7, 1983, C9. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeZo53

“Three Generations of Glass Designers.” New York Times, April 7, 1983, C9.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EeZo53

Hollister reviews glass by physicist Dr. Jesse T. Littleton, his son Harvey, and grandson John (along with collaborator Kate Vogel), on view in the exhibition Three Generations in Glass: The Littleton Family at Heller Gallery in Manhattan. Hired by Corning Glass Works in 1913, Dr. Littleton, the first PhD employed by the glass industry, is best known for his pioneering work in developing Pyrex cookware and his identification of the temperature at which glass melts. His son Harvey, represented in the show by sculptural assemblages, “laid the groundwork for the studio glass movement” and started the first university glassblowing program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1962. Harvey’s son John is a photographer and glassworker who collaborates with Vogel on “whimsical blown-glass drawstring bags in pastel shades.”

Corning Glass Works [later Corning Incorporated], Heller Gallery, Harvey Littleton, Jesse Littleton, John Littleton, Kate Vogel, University of Wisconsin-Madison

“Tom Patti: The Code Is in the Glass.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (April/June 1983): 74–83.

“Tom Patti: The Code Is in the Glass.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (April/June 1983): 74–83.

Although Hollister has trimmed words and minor details here and there, the text of this profile of Tom Patti is otherwise virtually identical to the one he published two months earlier in American Craft (vol. 43, no. 3) except for its closing paragraphs. Here, he inserts a critique of Patti’s work absent from the other version: “Occasionally, however, features are added that distract from the impression of unity of a given piece.” Three years earlier, Patti began incorporating plastic into some of his glass pieces, fusing the two materials so that “the cast plastic is virtually indistinguishable from the glass,” a development that may cause “collectors or critics to reevaluate his more recent work.” Patti also recently undertook a commission for a large sculptural work entirely in plastic, made for General Electric. Incl. illus. (3 b/w, 9 color) of work by Tom Patti. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist page for Bard Graduate Center transcript of audio recording held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Tom Patti Interview with Paul Hollister, 1983 (Corning BIB ID: 168377).

The Corning Museum of Glass, General Electric Co., Douglas Heller, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Marilyn Holtz Patti, Tom Patti, Pratt Institute, Kenneth Wilson

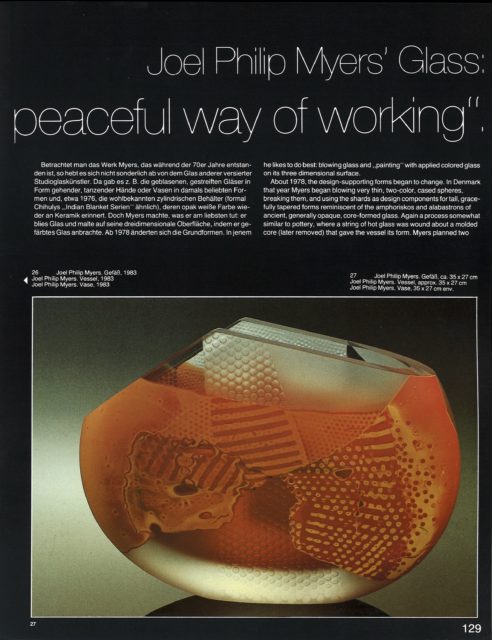

“Joel Philip Myers’ Glas: Eine ruhige, friedvolle Art zu arbeiten / Joel Philip Myers’ Glass: ‘A Quiet, Peaceful Way of Working’.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (July/September 1983): 128–133.

“Joel Philip Myers’ Glas: Eine ruhige, friedvolle Art zu arbeiten / Joel Philip Myers’ Glass: ‘A Quiet, Peaceful Way of Working’.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (July/September 1983): 128–133.

Hollister interprets Joel Philip Myers’s work in glass with reference to his early training in graphics and ceramics. He notes Myers’s career began in advertising and graphic design (BFA, Parsons School of Design, 1954) and shifted to clay, culminating in an MFA from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University. Myers switched to glass in 1963 and became director of design at Blenko Glass Company in Milton, West Virginia, where he remained until he joined the faculty of Illinois State University in 1970. Hollister describes in detail the forms and techniques that distinguish Myers’s work from that of other glassblowers. Around 1978, the artist began applying thin, shell-like fragments of colored glass onto a blown “more or less spherical bubble,” then rolling it on a marver to make the surface flush. Initially relying on black or white opaque glass with a dull, matte surface for the blown vessel or background, he began using clear glass during a residency at Pilchuck Glass School. Since 1980, Myers “has taken a giant stride forward,” producing bigger, bolder, flattened vessels with deeper, more translucent layers of glass, patination and texturing, and sliced top edges. For Hollister, “These fine pieces have a massive presence and unity that seems lacking in even larger, heavier pieces blown by other glass artists,” with an “orchestration of color about form [that] makes a statement for our time.” Incl. illus. (3 b/w, 5 color) of work by Joel Philip Myers.

Blenko Glass Company, Dale Chihuly, Detroit Institute of Arts, Huntington Galleries [later Huntington Museum of Art], Jesse Besser Museum, Illinois State University, Richard Kjaergaard, Kunsthaandvaerkerskolen Copenhagen, Joel Philip Myers, New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Parsons School of Design, Pilchuck Glass School, Seneca Glass Company, West Virginia Glass Specialty Company

“Studio Glass: A Gallery’s Show of Pâte-de-Verre.” New York Times, October 13, 1983, C7. Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V2TCsU

“Studio Glass: A Gallery’s Show of Pâte-de-Verre.” New York Times, October 13, 1983, C7.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V2TCsU

The current exhibition of pâte de verre at the Heller Gallery in New York City combines new work by emerging artist Doug Anderson and pieces by nineteenth-century French makers such as Amalric Walter, François Décorchemont, and Gabriel Argy-Rousseau, including loans from Minna Rosenblatt. An ancient technique, pâte de verre was revived by Henri Cros in France in the mid-1880s and adopted by the French artists in the show and others for its ability to convincingly portray items drawn from nature. Like his predecessors, Anderson fuses crushed glass, powdered enamels, and metallic oxides in molds cast from life. Works such as Fish Bowl, Mail Fish, and Fish’ n Chips include cases made from dead bluegills and evince both technical excellence and a sense of whimsy.

Doug Anderson, Argy-Rousseau, Henri Cros, François Décorchemont, Georges Despret, Loie Fuller, Heller Gallery, Minna Rosenblatt, Amalric Walter

“Gefühle—personifiziert: Arbeiten von Flora Mace und Joey Kirkpatrick / Personification of Feelings: The Mace/Kirkpatrick Collaboration.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): 14–19.

“Gefühle—personifiziert: Arbeiten von Flora Mace und Joey Kirkpatrick / Personification of Feelings: The Mace/Kirkpatrick Collaboration.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): 14–19.

In this article, Hollister focuses on the collaboration between artists Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick. The pair coexecute “flat cloisonné illustration on hot glass” through a process of reproducing pencil drawings in wire, incorporating the wire into glass forms during the blowing process, and using lampwork techniques to finish the images. Mace, who learned to weld as a child, drew upon her metalworking skills to create large wire-and-bead sculptures at New Hampshire’s Plymouth State College (BS, 1972). At the University of Illinois (MFA, 1976), she began making pieces using drawn-glass threads based upon her interest in the “flow of line.” In the mid-1970s, she produced designs for Dale Chihuly. Kirkpatrick received a BFA in drawing from the University of Iowa in 1975 before pursuing graduate work in glass at Iowa State University. The two first met in 1979 at Pilchuck Glass School, where Mace was teaching and Kirkpatrick was enrolled as a student. Mace helped Kirkpatrick execute her drawings in glass, first with glass threads and then with wire. The selection of their jointly produced pieces for a show forced them “to come to terms with whose work it was.” Their decision to cosign it—unusual in the studio glass world—led to their ongoing artistic collaboration. Hollister describes their process in detail and discusses Mace’s desire to avoid becoming “a mere technician.” Incl. illus. (5 b/w, 4 color) of work by Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick. Editor’s note: Paul Hollister recorded research material related to this article. See linked artist pages for Bard Graduate Center transcripts of audio recordings held by The Rakow Research Library of The Corning Museum of Glass: Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace Self-interview for Paul Hollister, September 30, 1983 (Corning BIB ID: 168374).

Dale Chihuly, Joey Kirkpatrick, Flora Mace, Henri Matisse, Pilchuck Glass School, Rhode Island School of Design

“Glass America 1984.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): 27–28.

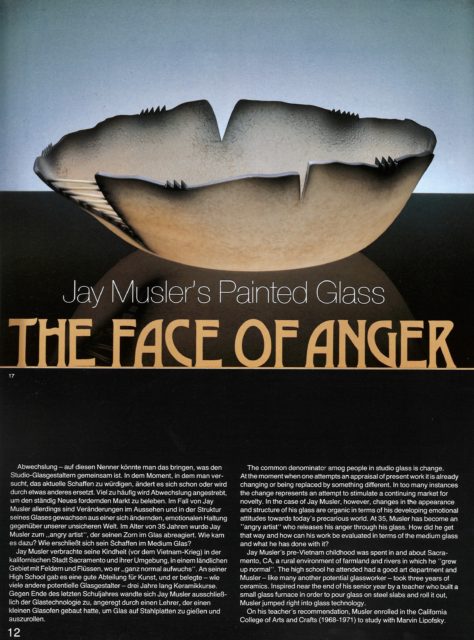

“Glass America 1984.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): 27–28.