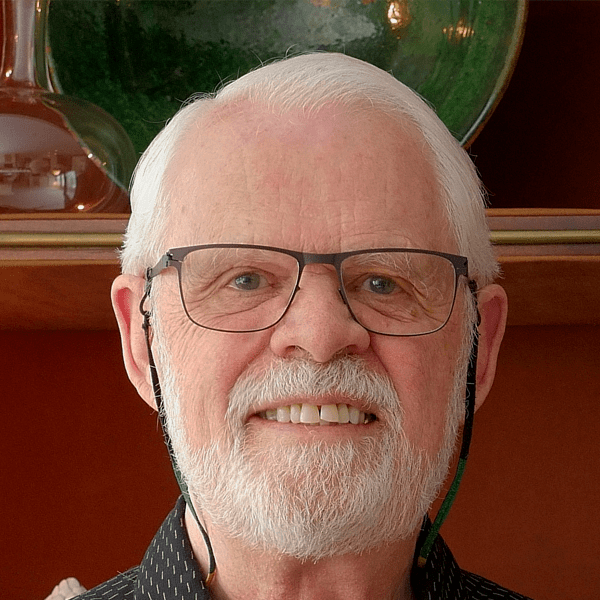

Dwight Lanmon discusses his and Paul Hollister’s work on selecting paperweights for The Great Paperweight show, contemporary weights in the exhibition, and the accompanying Corning Seminar. Oral history interview with Dwight Lanmon by Catherine Whalen and Barb Elam, conducted via telephone, August 5, 2019, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 04:51.

Time stamp: 00:00

Clip 1: Dwight Lanmon discusses how his and Paul Hollister’s taste aligned while selecting paperweights for Corning’s Great Paperweight Show. Clip length: 01:24.

Dwight Lanmon: We traveled throughout New England and the Mid-Atlantic states talking to paperweight collectors, and it was always sort of interesting non-stop conversation as we were driving around. And what was interesting to me is that we never disagreed about which paperweights to include. When I didn’t like something, he didn’t like it, and vice versa. So we were well attuned to each other’s taste in terms of the paperweights we wanted to show. And as I said in the long section of discussion about the show, our aim was to show the greatest paperweights we could find. And that meant two things: artistically and technically. And—you know—you could have a beautiful weight that had a serious flaw, like a flower that had a petal out of place—or something. And we thought that wrecked it. Even though the paperweight might have been beautiful, if you looked at it closely, and most people would only see them in the book, it would be a defect, and we tried as best we could not to have any paperweights with visual defects.

Time stamp: 01:27

Clip 2: Dwight Lanmon discusses his and Paul Hollister’s commitment to making serious contributions to paperweight scholarship. Clip length: 01:28.

Dwight Lanmon: It was serious scholarship, first of all, and that has always been important to me, as opposed to, ‘Isn’t that pretty?’ And Paul really looked at them, and tried to figure out what they were, and talked about them aesthetically and technically in the catalog. And he and I met, I had met Paul, I don’t know how, but, early on in my career at Corning, and I just thought, ‘Well, what we want to do is not only show the greatest paperweights, but also make a serious contribution to understanding paperweights.’ So in addition to the catalog, the Flowers catalog, I measured the density of every weight in the show, and—so that we could begin to classify things technically. And also I did ultraviolet of every one and so it became a big joke that Lanmon could only tell where a paperweight was made when the lights are out. And looking at things under ultraviolet, but I did find that there were lots of things that simply were not true, that had been published in the past in terms of attribution. So there is a density chart for almost every paperweight that is shown in the catalog. And so as I say, we were trying to take the study and understanding of paperweights to a new level when we did the show.

Time stamp:0 2:52

Clip 3: Dwight Lanmon discusses pieces in The Great American Paperweight Show that weren’t in the catalogue. Clip length: 00:48.

Dwight Lanmon: So there are sixty-eight additional pieces that were not in the catalog that were in the show. There are a lot of early things we tried to put paperweights into perspective. We had a sixteenth, seventeenth century tazza from Venice, an ewer—same date. Roman millefiori plaques, Roman filigree bowl [inaudible]. So there are a lot of ancient things, but then a lot of contemporary. We had one exhibition case that was entirely full of contemporary weight makers. Nick [Dominick] Labino paperweight that was lent by Nick. Max Erlacher a piece that he did. Andy [Andre] Bellici, Ray Banford, Bob Banford, all lent by the artists. Debbie Tarsitano, lent by [Paul] Jokelson. Paul Ysart lent by Jokelson.

Time stamp: 03:43

Clip 4: Dwight Lanmon talks about the Corning Seminar on The Great Paperweight Show. Clip length: 01:08.

Dwight Lanmon: Well, I never heard anybody criticize the exhibition or the catalog, and the glass seminars at Corning, the annual seminar, one of the first ones that we did that was a special subject seminar after I went there as chief curator, was the 1978 program at—which we did entirely on paperweights and on related things, millefiori and that sort of thing. And it was, as I recall, it was the largest attendance that we’d ever had, and before I went to the museum and they had these general seminars, you’d get 30, 40 people, and it would typically be the same people year after year, which was great because you got to know the people. But I think for the paperweight seminar we had like 145 show up, so it was a huge difference and that was for me, very heartening. And encouraging, so they wanted to see the show, and a lot of the lenders were there for the seminar, and then some pieces came to the museum afterwards as gifts, that were in the show, that were privately held. So that was pleasing to me, as well.

Permalink