The Corning Museum of Glass

Corning, NY

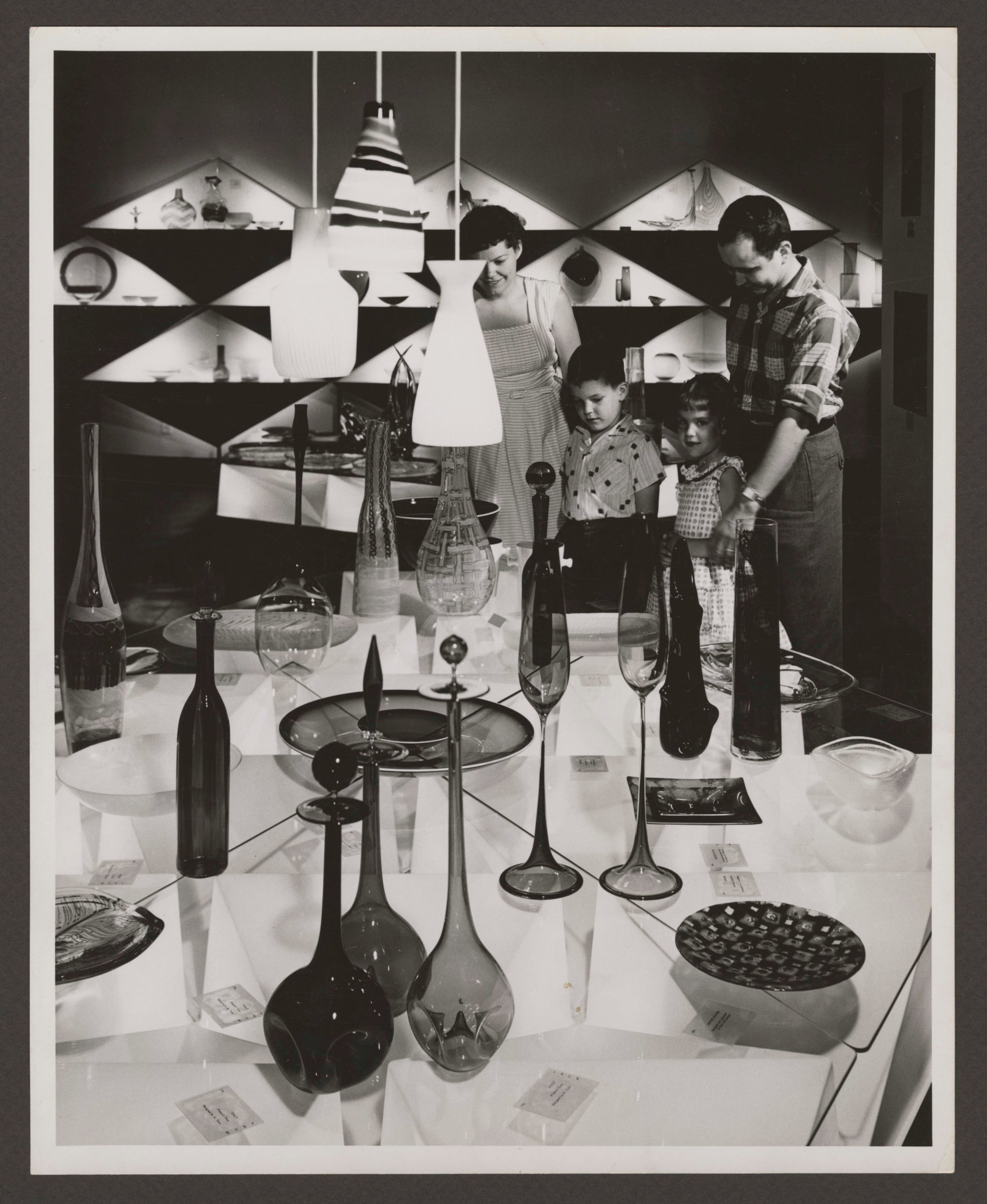

Modern Glass Gallery, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Introduction

In 1951, in celebration of its hundredth anniversary, Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated) established The Corning Museum of Glass in the company’s hometown of Corning, New York. Since its beginning, the museum has maintained both an extensive collection of glass—it currently holds more than fifty thousand objects spanning three and a half millennia—and a substantial research library. The museum has permanent exhibitions showcasing the history and science of glass; organizes temporary exhibitions; publishes scholarly and artistic journals; provides public glassworking demonstrations; and offers resources for glass artists and students. As The Corning Museum of Glass has grown, it has significantly revised its campus. Paul Hollister wrote an enthusiastic review of the museum’s first major reorganization, which included the opening of a dramatic new building in 1980.

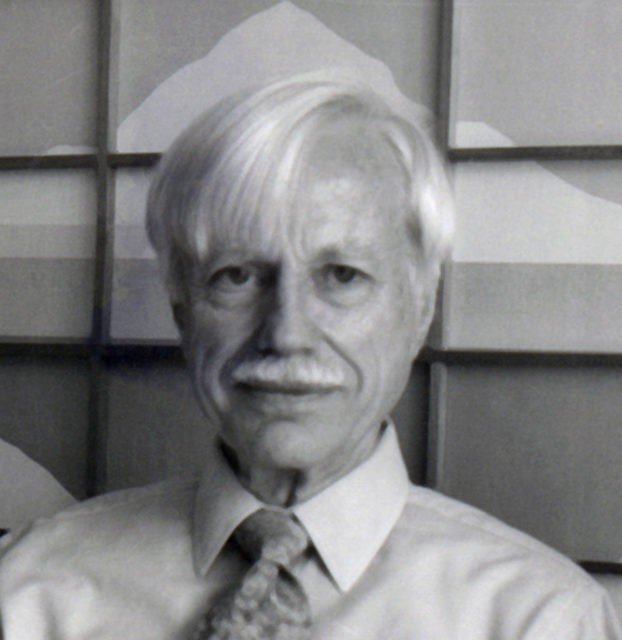

The Corning Museum of Glass strongly spurred the studio glass movement by strengthening artistic exchange and public interest in contemporary glass and by providing support for artists. This section explores a few of the memorable Corning exhibitions that documented and altered the direction of studio glass, as well as influential initiatives like its glass studio and annual publication, New Glass Review. It also describes Corning’s own early and ongoing involvement with art glass through its Steuben division, whose lasting influence is attested to in Corning Museum exhibits on the division’s cofounder Frederick Carder. Featured, too, are excerpts from a 1983 interview with Věra Liškova by Paul Hollister, and interviews and correspondence, from 2016 to 2020, with James Carpenter, Michael Glancy, William Gudenrath, Ferdinand Hampson, Douglas Heller, Dwight Lanmon, Tina Oldknow, Mary Shaffer, Susie Silbert, Paul Stankard, Debbie Tarsitano, Victor Trabucco, and Toots Zynsky. The section also includes archival images of key exhibitions, a transcript of Paul Hollister’s walk-through of Corning’s New Glass: A WorldWide Survey exhibition (1979), and an audio excerpt from the recording. In addition, there is a transcript of lectures on paperweights given by Hollister and Dwight Lanmon and a list of selected publications and related research by Hollister highlighting his engagement with The Corning Museum as a curator and critic.

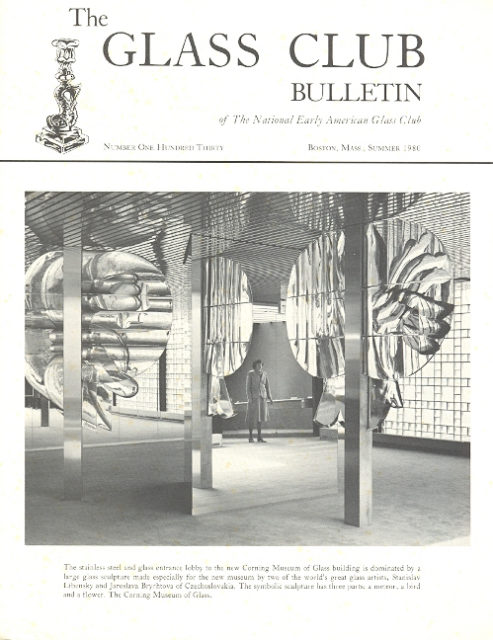

“The New Corning Museum of Glass, a Personal View.” Glass Club Bulletin, no. 30 (Summer 1980): 3–5.

“Hollister on Glass: Corning’s Glass Mecca.” Collector Editions 8, no. 4 (Fall 1980): 34.

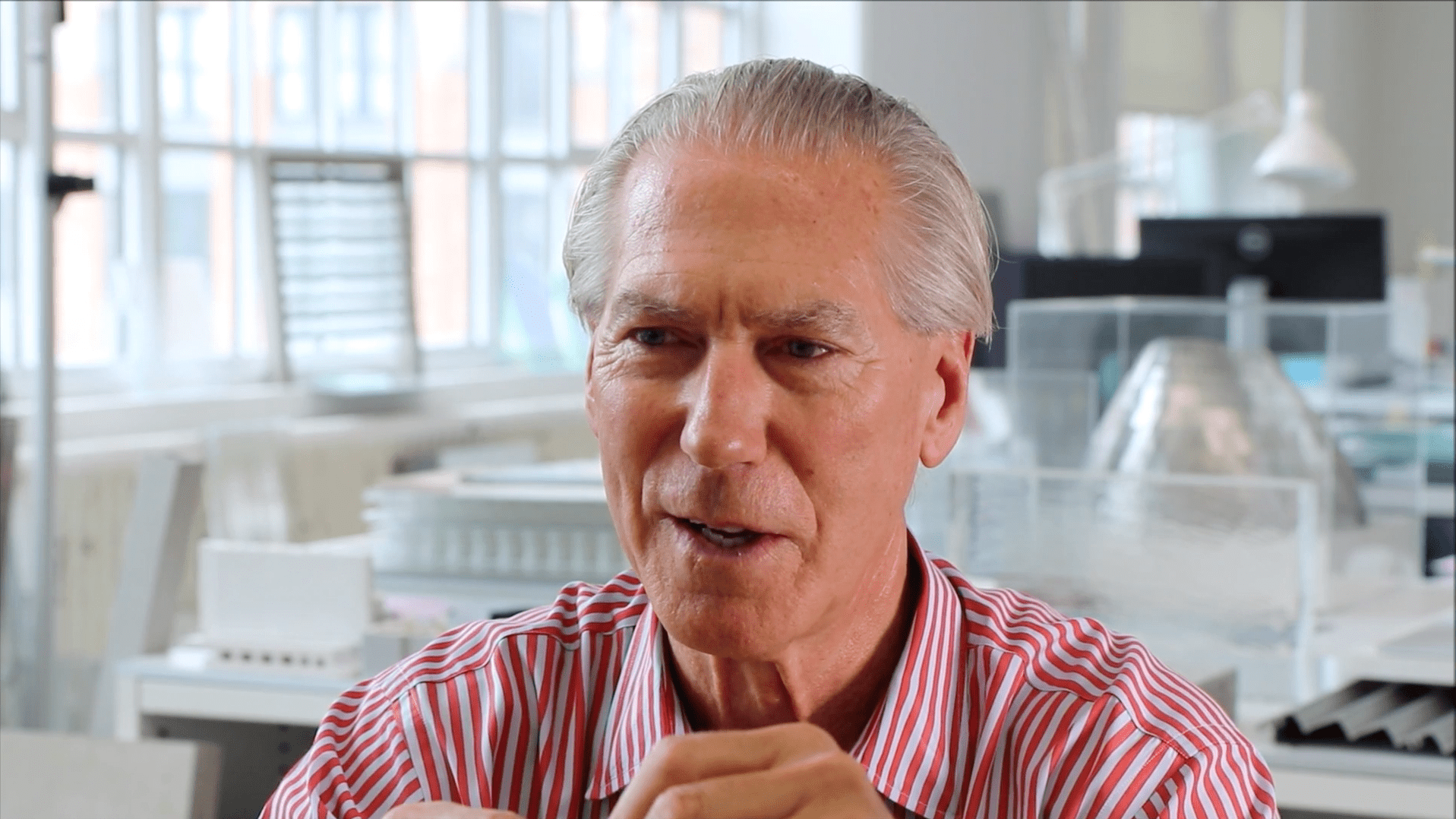

Former Corning Museum of Glass Director Dwight Lanmon discusses the impetus to “make glass interesting” to the public.

01:52 Transcript

Corning Glass Works and Steuben

Corning Glass Works began in the mid-1800s as a maker of functional scientific and household objects. The company acquired the nearby Steuben Glass Works, known for its decorative art glass, in 1918, and maintained it as a separate division. Steuben, named after the New York county in which the city of Corning is located, was founded in 1903 by Thomas G. Hawkes and the English designer Frederick Carder. When in 1951 the Corning Museum opened next to the Steuben’s facilities, visitors could watch company glassblowers at work through a window designed for this purpose. The following year, the museum staged the exhibition Frederick Carder, His Life and Work, highlighting the Steuben cofounder’s long career.

Frederick Carder’s Influence

Frederick Carder’s work as a glass designer and artist left its mark on early leaders and observers of the studio glass movement. Harvey Littleton, an essential figure in the movement, greatly admired Carder. Littleton grew up in the city of Corning, where his father, Dr. Jesse Talbot Littleton, was Corning Glass Works’ first physicist. Carder lived near the Littleton family, and he ran Corning’s board of education. He continued to work in glass after leaving Steuben in 1932 and became especially known for cast glass sculptures. The Corning Museum of Glass has devoted an entire gallery to Carder, with many objects on loan from the nearby Rockwell Museum, founded by Carder’s longtime friend and collector Robert F. Rockwell, Jr. Paul Hollister, long interested in Carder’s work, contributed an essay to the catalogue for the Rockwell’s 1993 show Brilliance in Glass: The Lost Wax Glass Sculpture of Frederick Carder. Carder did not get a chance to see studio glass flourish; he died at the age of one hundred, a year after Littleton’s 1962 workshops at the Toledo Museum of Art demonstrated that glassblowing could be done by artists outside the factory.

Transition and the Houghton Years

As Steuben lost money during the economic depression of the 1930s, Corning Glass Works substantially reorganized. The company turned to new director Arthur Amory Houghton, Jr., a great-grandson of Corning’s founder, to lead the process. Carder stepped down from Steuben and became artistic director for Corning Glass Works. Houghton transitioned Steuben away from the brightly colored glass that had been its specialty and focused on Corning’s recently developed clear crystal. He also established Steuben’s design department. Under Carder, expert glassblowers had both designed and made Steuben’s wares. Houghton separated these processes, hiring designers to develop objects with consumer appeal to be produced in quantity by Steuben’s skilled artisans. Noted industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague came on board as a consultant and developed modern tableware designs. Houghton then brought Steuben design in-house, hiring architect John M. Gates as Steuben’s managing director and sculptor Sidney Waugh as its chief associate designer.

About the same time, Steuben began collaborating with prominent contemporary artists. In 1937, it commissioned twenty-seven artists—including Salvador Dalí, Henri Matisse, Isamu Noguchi, and Georgia O’Keeffe—to create designs that were engraved on crystal vessels and exhibited as 27 Artists in Crystal. Later, Corning Museum of Glass Founding Director Thomas S. Buechner brought Steuben’s artist-designers to the forefront when he became president of the company in 1972. Studio glass artists such as Paul Schultz (design director), James Carpenter, David Dowler, Peter Aldridge, and Jane Osborn-Smith designed unique pieces for Steuben. During the 1970s, Dwight P. Lanmon, then director of the museum, invited Steuben designers to view historical glass in the museum’s collection. Despite some initial reluctance, they warmed to drawing inspiration from the museum’s holdings.

Steuben has consistently referenced its own history, bringing back into production pieces by designers like Dorwin Teague and reintroducing glassmaking techniques popularized by Carder. Both Steuben and Corning as a whole have consulted with glass artists to improve production. For example, James Carpenter, a designer for Steuben, spent ten years (1972–1982) as a consultant at Corning, where he experimented with the photosensitive glass that later informed his architectural practice. Paperweight maker and inventor Victor Trabucco created a polishing machine that Steuben began using in the early 2000s, and the firm redesigned its cold shop based on Trabucco’s specifications.

Further Reading: Mary Jean Madigan, Steuben Glass: An American Tradition in Crystal (New York: H. N. Abrams, 2003).

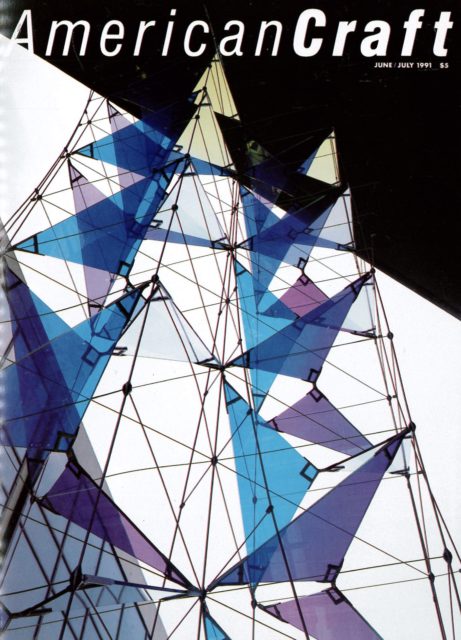

“James Carpenter: Adventures in Light and Color in Space.” American Craft 51, no. 3 (June/July 1991): 28–35.

Blue Aurene Vase, Frederick Carder, Steuben Glass Works, Corning, New York, c. 1920s. Transparent cobalt lead glass, iridescent blue surface. Overall H: 31.7 cm, Diam (max): 30.1 cm Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of Frederick A. Seib in memory of Mr. & Mrs. Frederick G. Seib. (94.4.65).

Whisper Whiskey Set, Steuben, 2018. Lead crystal. Decanter H: 9 in, W: 4 in., Glasses H: 3.5 in, D: 3.5 in. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Corning Museum of Glass Curator of Modern and Contemporary Glass, Susie Silbert discusses the relationship between Corning Glass Works and The Corning Museum of Glass.

00:47 Transcript

Michael Glancy discusses James Carpenter’s experience as a designer at Corning Glass Works.

01:19 Transcript

The Studio

In the mid-1990s, The Corning Museum of Glass expanded its educational mission beyond collections and research into hands-on glassmaking, adding a state-of-the-art glass studio. Accessible to the public, The Corning Museum of Glass Studio has functioned as both a school and an artistic resource, offering classes in glassworking and artist residencies. Artist William Gudenrath and educator Amy Schwartz oversaw the Studio’s planning and opening in 1995, with Gudenrath as resident advisor and Schwartz as director.

Entrance, The Corning Museum of Glass Studio. Courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

The Corning Museum of Glass Studio. Courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Corning Museum of Glass Permanent Artist in Residence, William Gudenrath discusses the history of The Corning Museum of Glass and his role as the Head and Resident Advisor of the Studio.

2:03 TranscriptInfluential Exhibitions

The Corning Museum of Glass has regularly organized and staged special exhibitions on specific topics since its opening in 1951. Some of these shows—featuring ancient to contemporary glass—have significantly influenced glass artists, scholars, and collectors and remain important touchstones in the field.

New Glass at Corning: Glass 1959, New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979), and New Glass Now (2019)

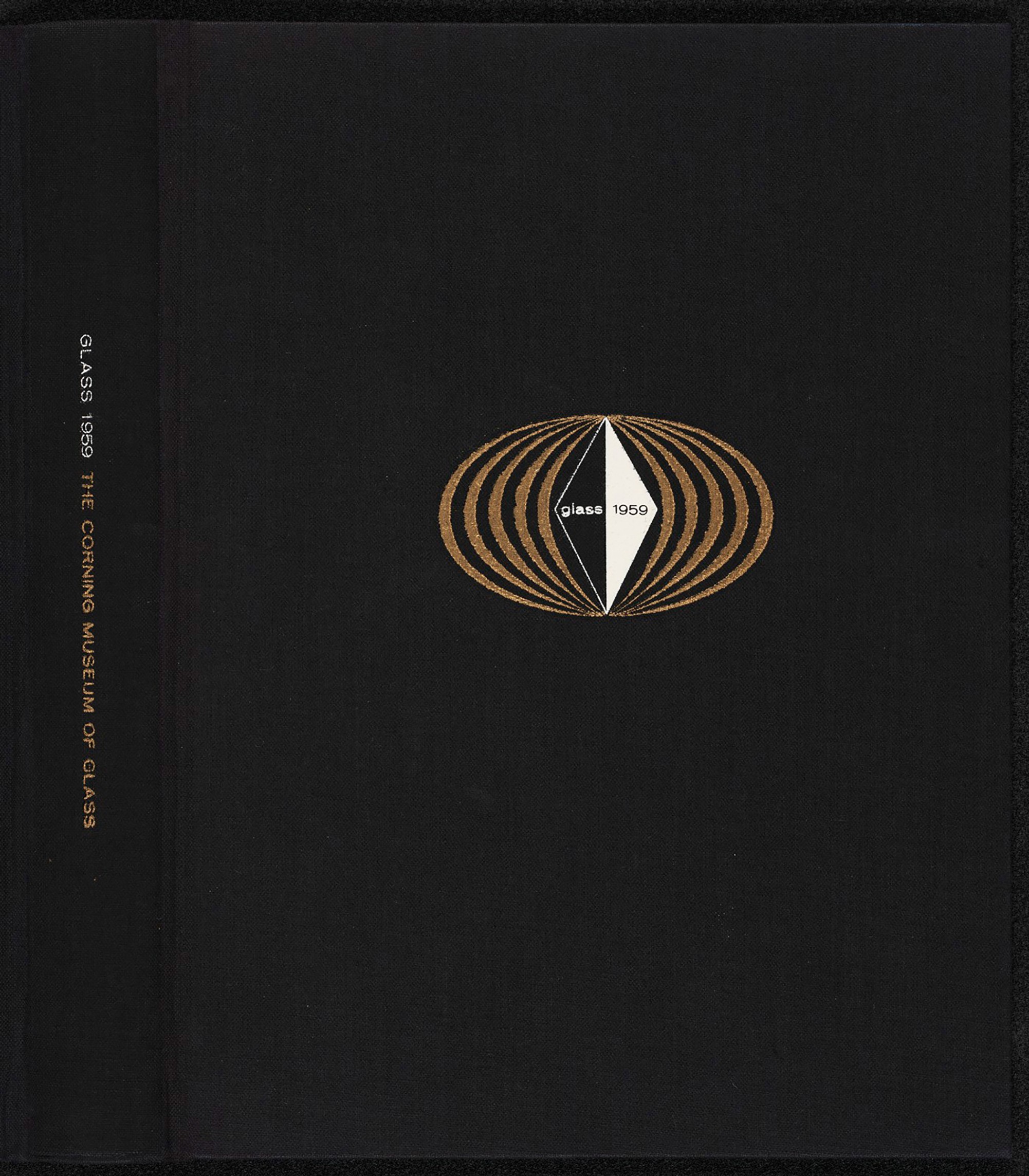

Cover. Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 27614).

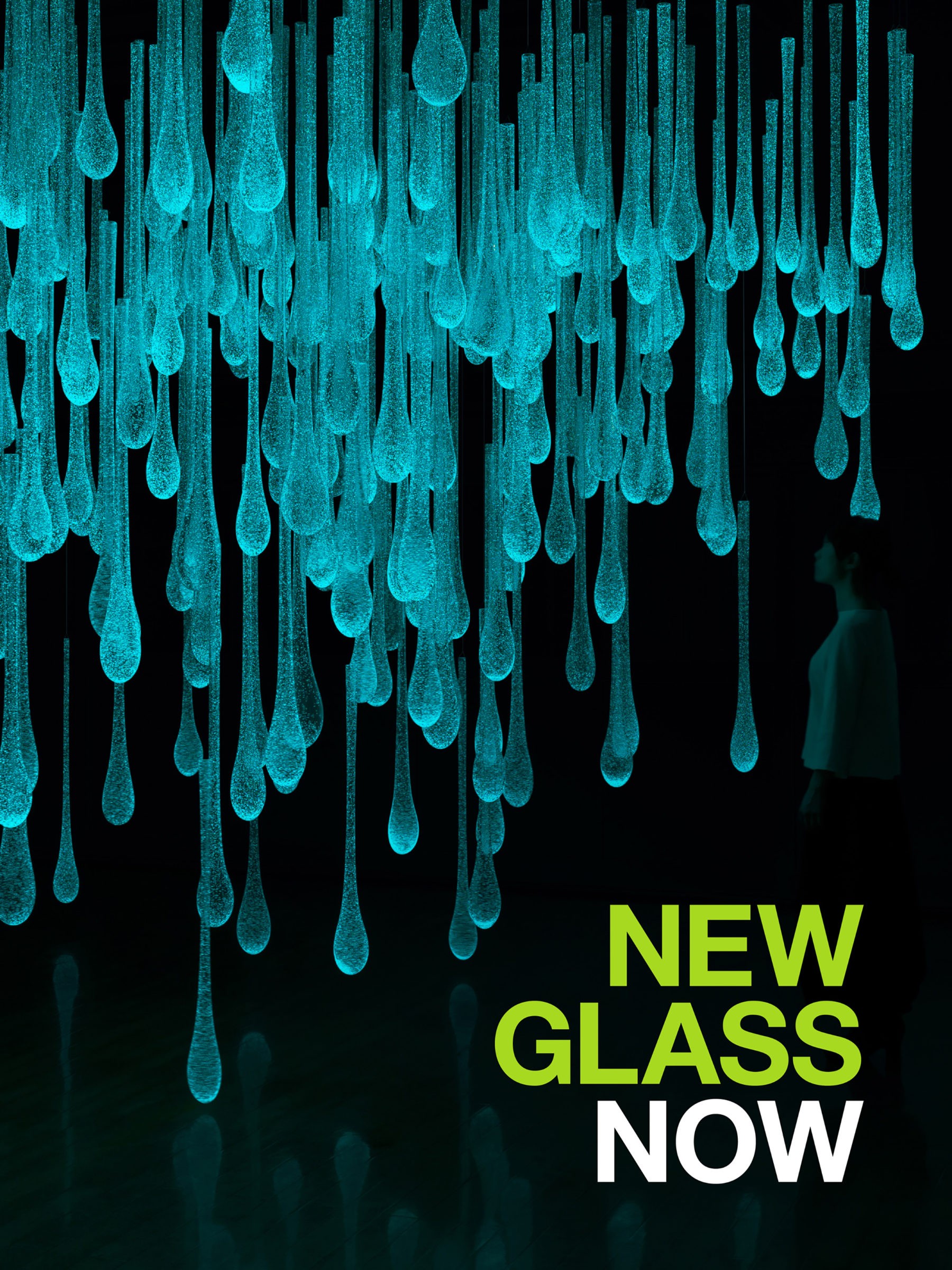

Cover. New Glass Now (2019), featuring image of Rui Sasaki’s Liquid Sunshine/I am a Pluviophile. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 37677).

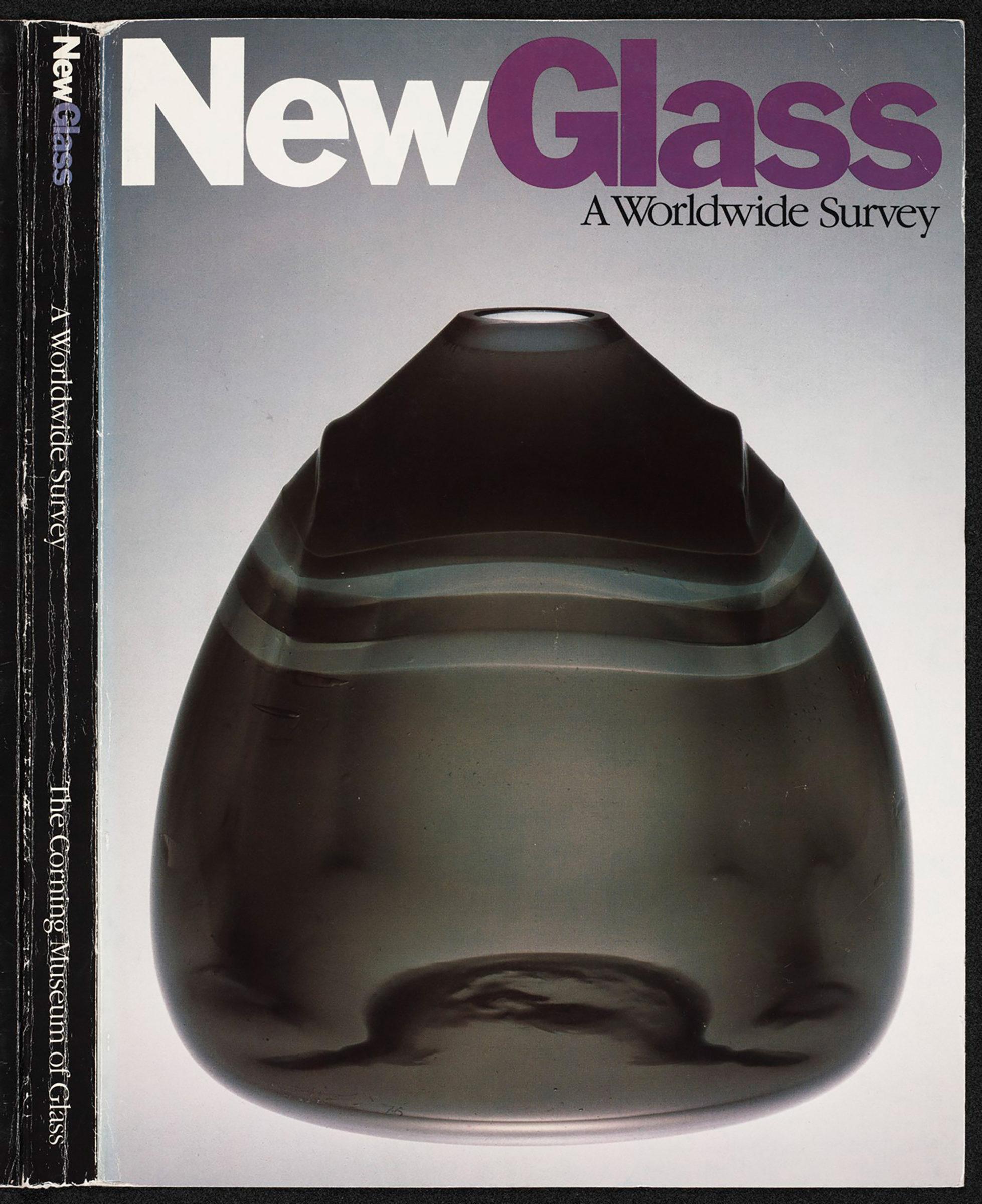

Cover. New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979), featuring image of Tom Patti’s Banded Bronze. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 20603).

In 1959, 1979, and 2019, the Corning Museum staged state-of-the-art international surveys of contemporary glass. These influential exhibitions and their accompanying catalogues led to greater awareness of and heightened interest in recent work in the medium. Together, these shows marked important developments in the field over a sixty-year period.

Susie Silbert discusses the geographic and demographic growth of artists in the three Corning glass survey shows.

Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass

The Corning Museum’s 1959 survey of contemporary glass generated unprecedented interest in the field. Organized by the museum’s founding director, Thomas S. Buechner, the exhibition of 292 objects began with an open call that resulted in submissions from around the globe. The entries were assessed by five jurors: Leslie Cheek, Jr., director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., former director of the Industrial Design Department at the Museum of Modern Art; Russell Lynes, editor of Harper’s Magazine; architect and woodworker George Nakashima; and architect and designer Gio Ponti. The objects they selected represented individual and corporate makers in twenty countries. Most were mass produced and available for public purchase, but unique sculptural works also were included. By bringing together such a large array of contemporary glass, the exhibition presented to the public the medium’s possibilities for art and design. The show subsequently traveled to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Chrysler Museum of Art.

Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass, Installation view. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 714711).

Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass, Installation view. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 713974).

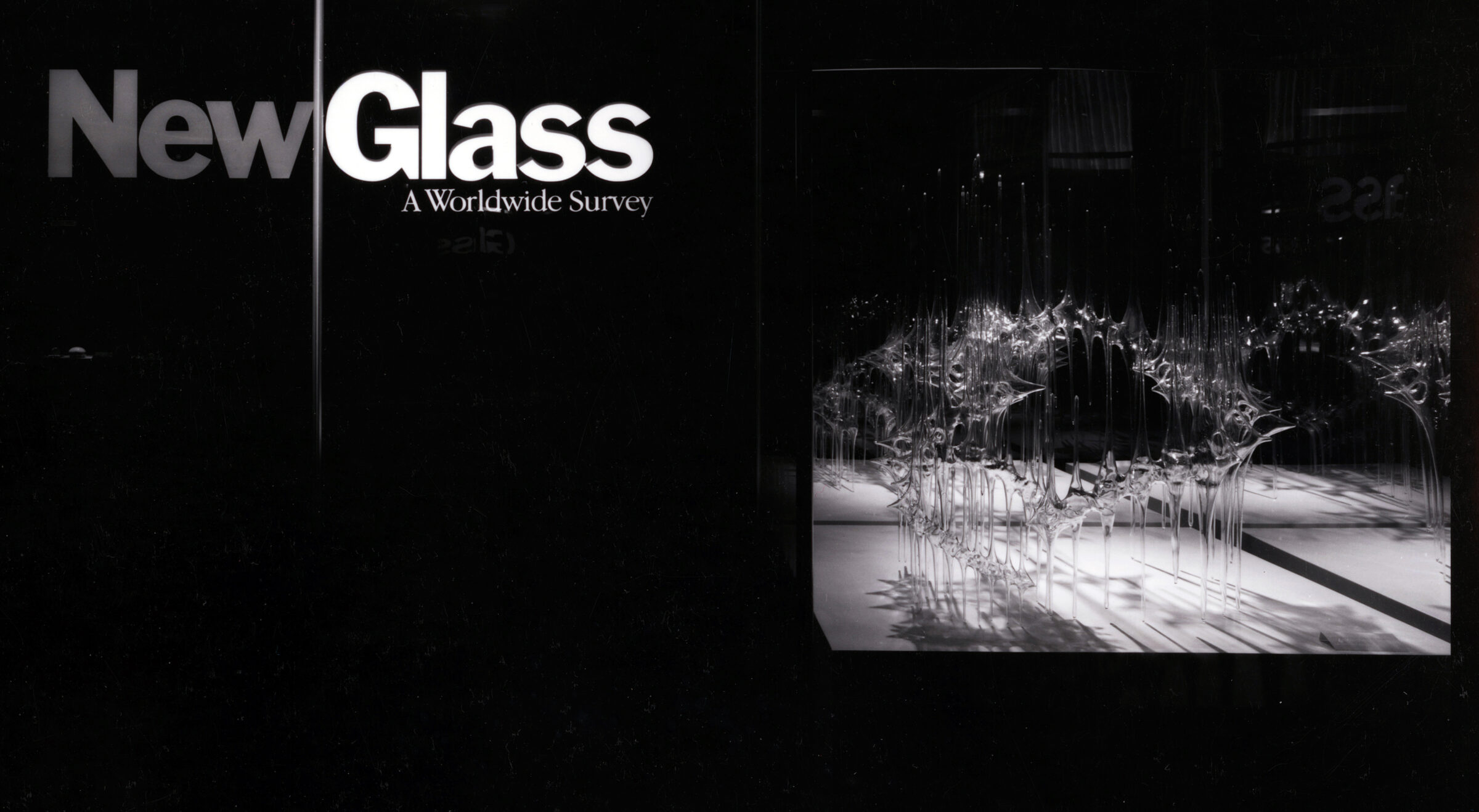

New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979)

Twenty years later, Buechner reprised the 1959 selection process to develop New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979) with project director Antony Snow and assistant curator William Warmus. A panel comprising Franca Santi Gualteri, editor of Abitare magazine; Russell Lynes (again); Werner Schmalenbach, director of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, in Düsseldorf; and Paul J. Smith, director of the American Craft Museum, selected from among entries received in response to an international open call for submissions. This influential exhibition featured the work of nearly two hundred artists and organizations representing twenty-eight countries in North and South America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Twenty-four artists were from Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) alone. The show traveled to the Toledo Museum of Art, the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The catalogue cover featured a single work, Tom Patti’s Banded Bronze. New Glass sparked new interest in the field, particularly among critics and individual and institutional collectors.

New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (April 26-October 1, 1979), Entrance to exhibition featuring Věra Liškova’s Anthem of Joy, Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (April 26-October 1, 1979), Installation view, Corning Museum of Glass. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

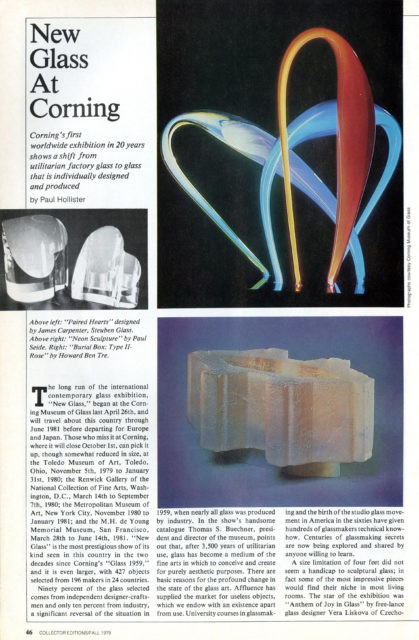

Paul Hollister and the ’79 Show

Paul Hollister described New Glass: A Worldwide Survey as “the most prestigious international display of glass seen in this country since Corning’s Glass 1959 show.” Prior to reviewing the exhibition for the New York Times and Collector Editions, Hollister tape-recorded his responses to the show as he progressed through its installation. In the recording, he identifies and describes the work of many artists, including the Americans Howard Ben Tré, whose name was then unfamiliar to him, James Carpenter, Dominick Labino, Tom Patti, and Steven Weinberg, all of whom later became focused subjects of his writing. Hollister admired the international work submitted as well. In particular, he extolled Anthem of Joy, by Czech designer Věra Liškova. This flameworked sculpture, made of borosilicate glass tubing, became part of Corning’s collection and did not travel to other venues. Hollister described the work as “absolutely marvelous,” explaining, “I can see it sitting for five hundred years in some showcase in some castle. It’s a pure fairytale piece in the most imaginative type—just beautiful.”1 In a later interview with Liškova, Hollister remarked, “You are the only one of the older group of people…who is doing something that is new and that belongs to this time in the world.”2 This section includes an audio clip from their conversation.

1Paul Hollister. Excerpt from audio recording made at New Glass: A Worldwide Survey, April 11, 1979.

2Paul Hollister. Excerpt from recorded interview with Věra Liškova, Feb. 10, 1983.

“New Glass at Corning.” Collector Editions 7, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 46–50.

“At Corning Glass Show, Sculptural Whimsy.” New York Times, April 26, 1979, C8.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2V2RmBW

Paul Hollister Recording for New Glass: A Worldwide Survey, April 11, 1979.

Paul Hollister records his observations while touring New Glass: A Worldwide Survey at The Corning Museum of Glass (1979).

(Rakow title: New Glass, Corning [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168418)

In a 1983 interview with Paul Hollister, Věra Lišková discusses her work with Lobmeyr, the acquisition of her pieces by the Museum of Modern Art, and her influences.

7:46 TranscriptPaul Hollister talks about Howard Ben Tré’s work at the New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979) exhibition.

1:35 TranscriptInternational Connections

The international scope of the work selected for New Glass: A Worldwide Survey proved revelatory, introducing American audiences to artists from around the world. American artists later traveled to Europe to study with those whom they had first encountered at New Glass 1979. Gallerists, too—particularly those specializing in contemporary glass, such as Ferdinand Hampson, founder of Habatat Galleries, in Michigan, and New York’s Heller Gallery cofounder Douglas Heller—made important connections with international artists at the exhibition. These new networks had a lasting impact on the range and quality of contemporary art glass exhibited and collected in the United States.

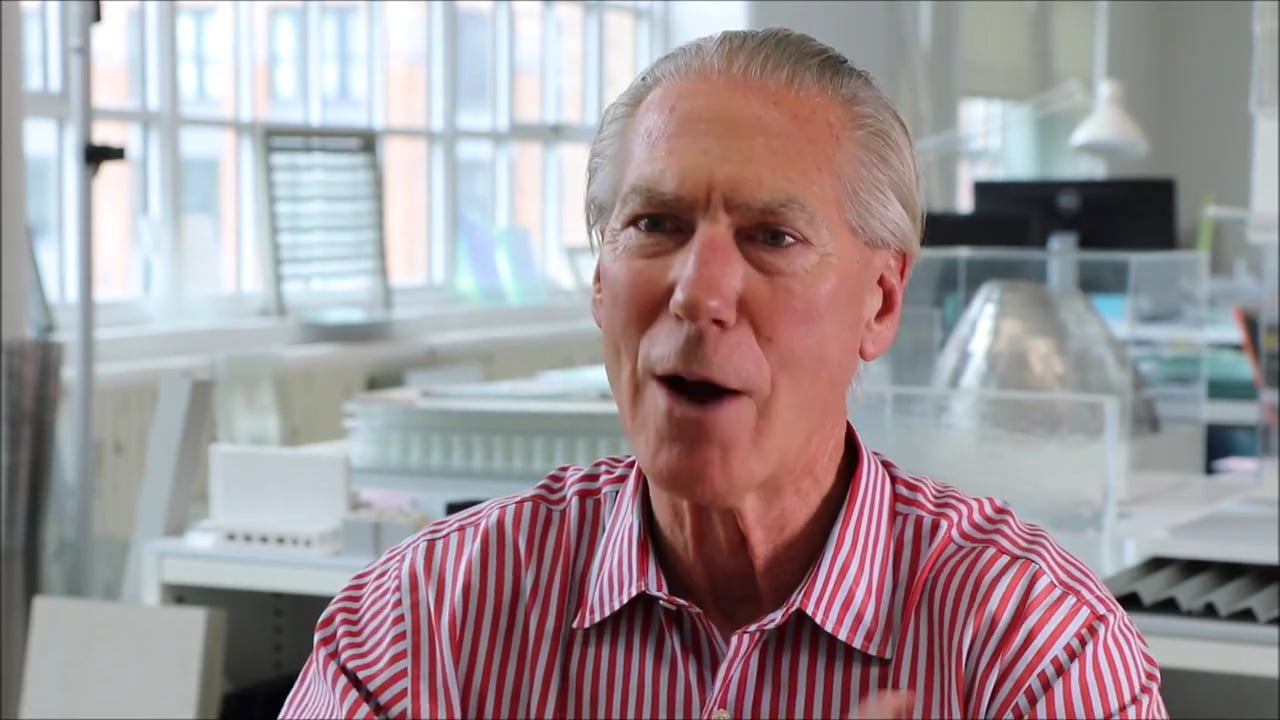

Douglas Heller talks about working more with European artists after seeing the Corning ‘79 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

01:37 Transcript

Douglas Heller discusses learning about a Czech artist through the Corning ‘79 show, whom he later represented.

01:03 Transcript

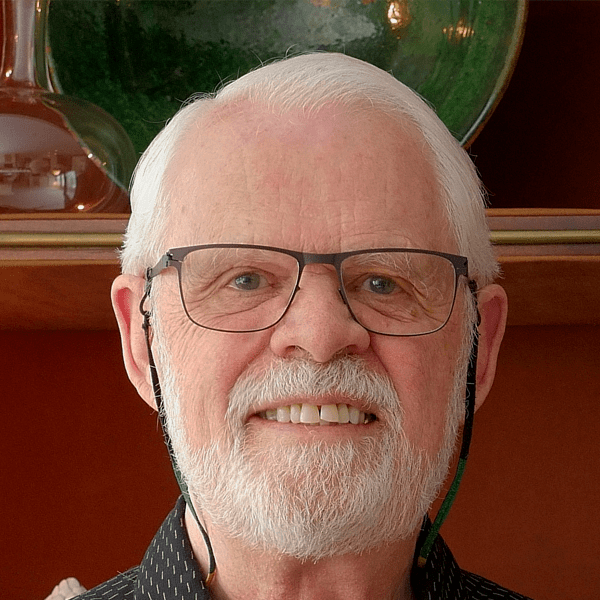

Dwight Lanmon discusses founding Corning Director Thomas Buechner’s importance to the studio glass movement.

01:04 Transcript

Ferdinand (Ferd) Hampson, founder of Habatat Gallery, discusses networking with artists from Eastern Europe at the Corning ‘79 show.

01:20 Transcript

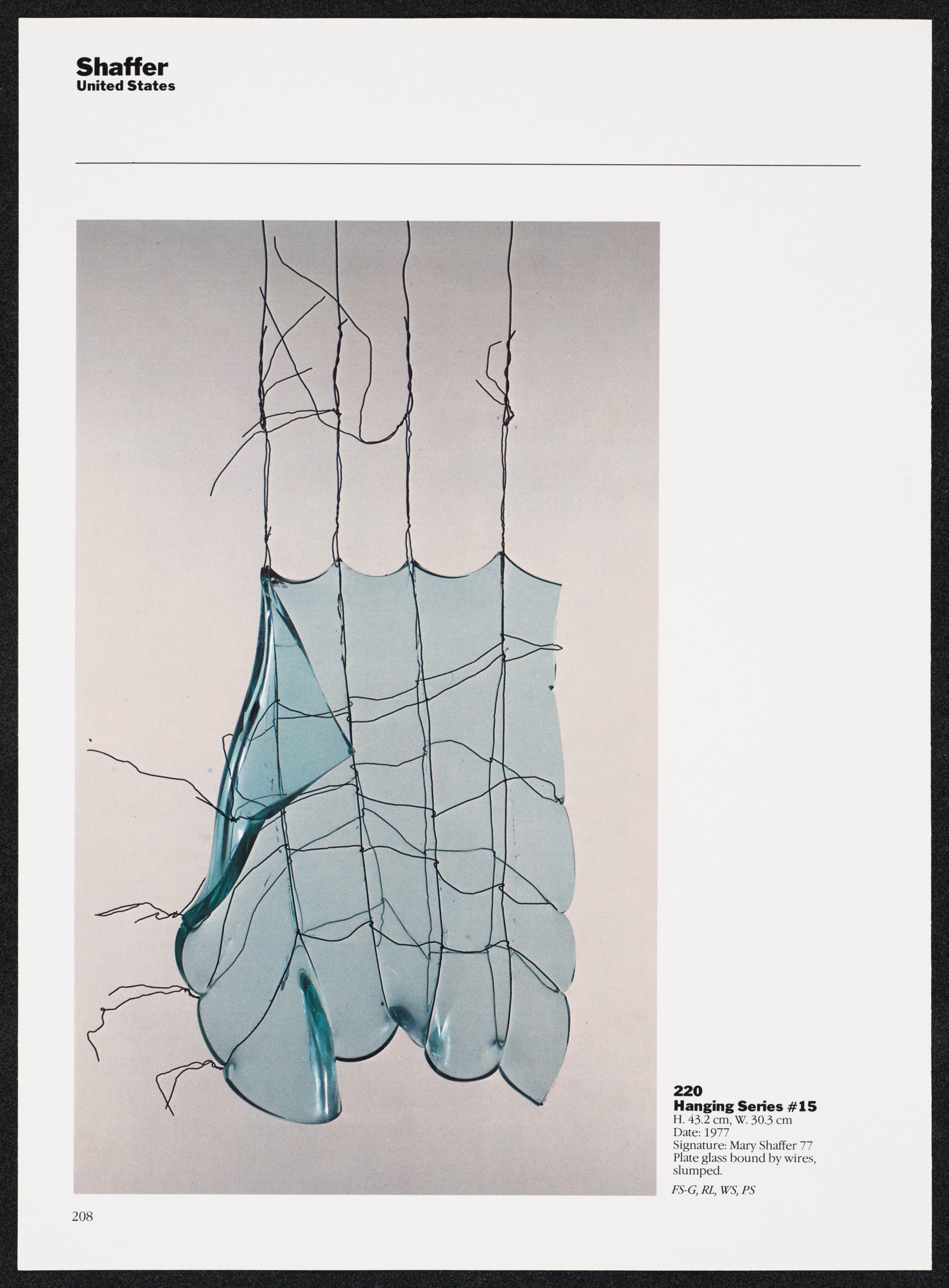

Mary Shaffer’s Hanging Series #15, 1977. Plate glass bound by wires, slumped, Overall H: 43.3 cm, W: 303 cm. In New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979), p. 208. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

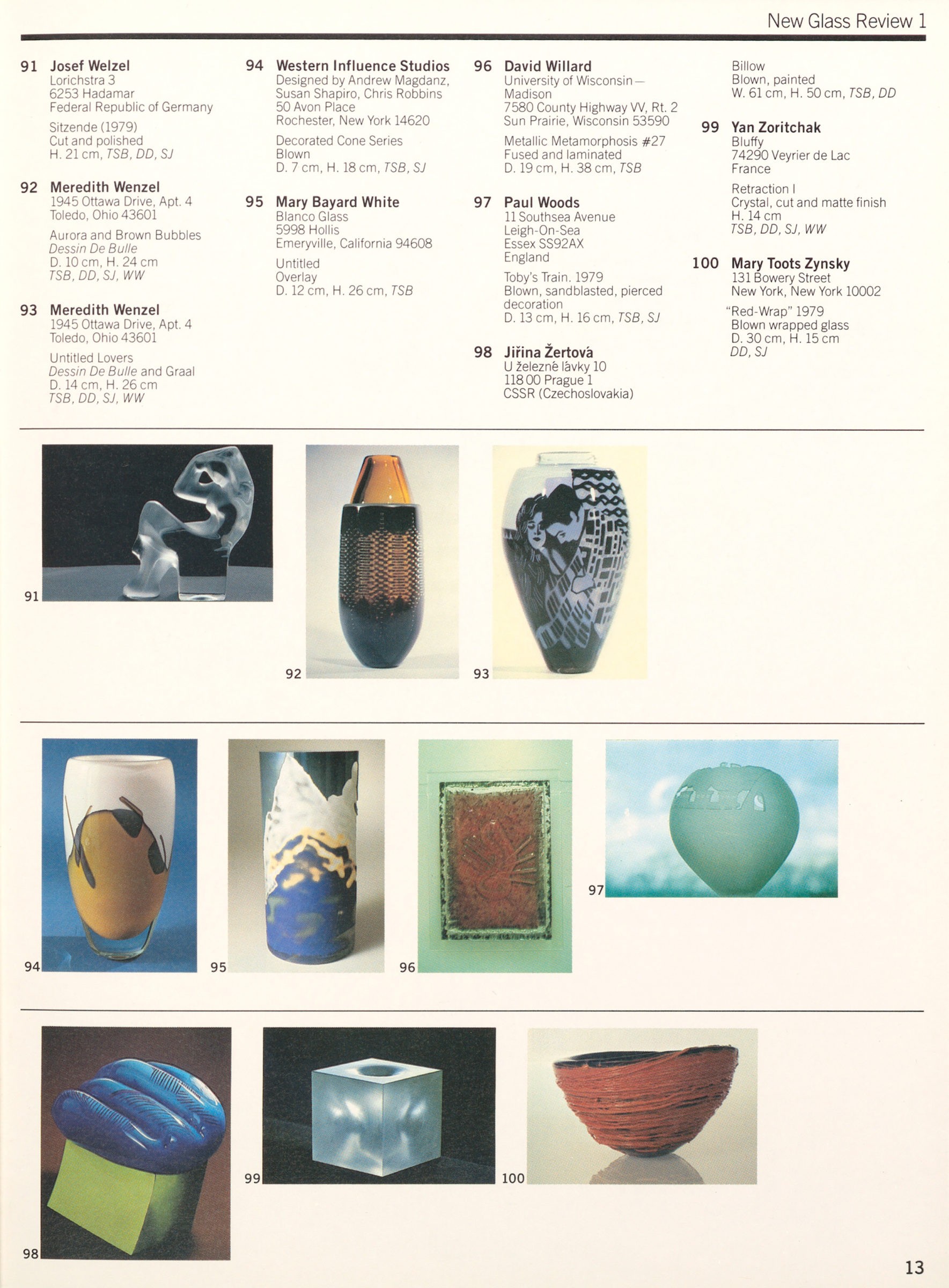

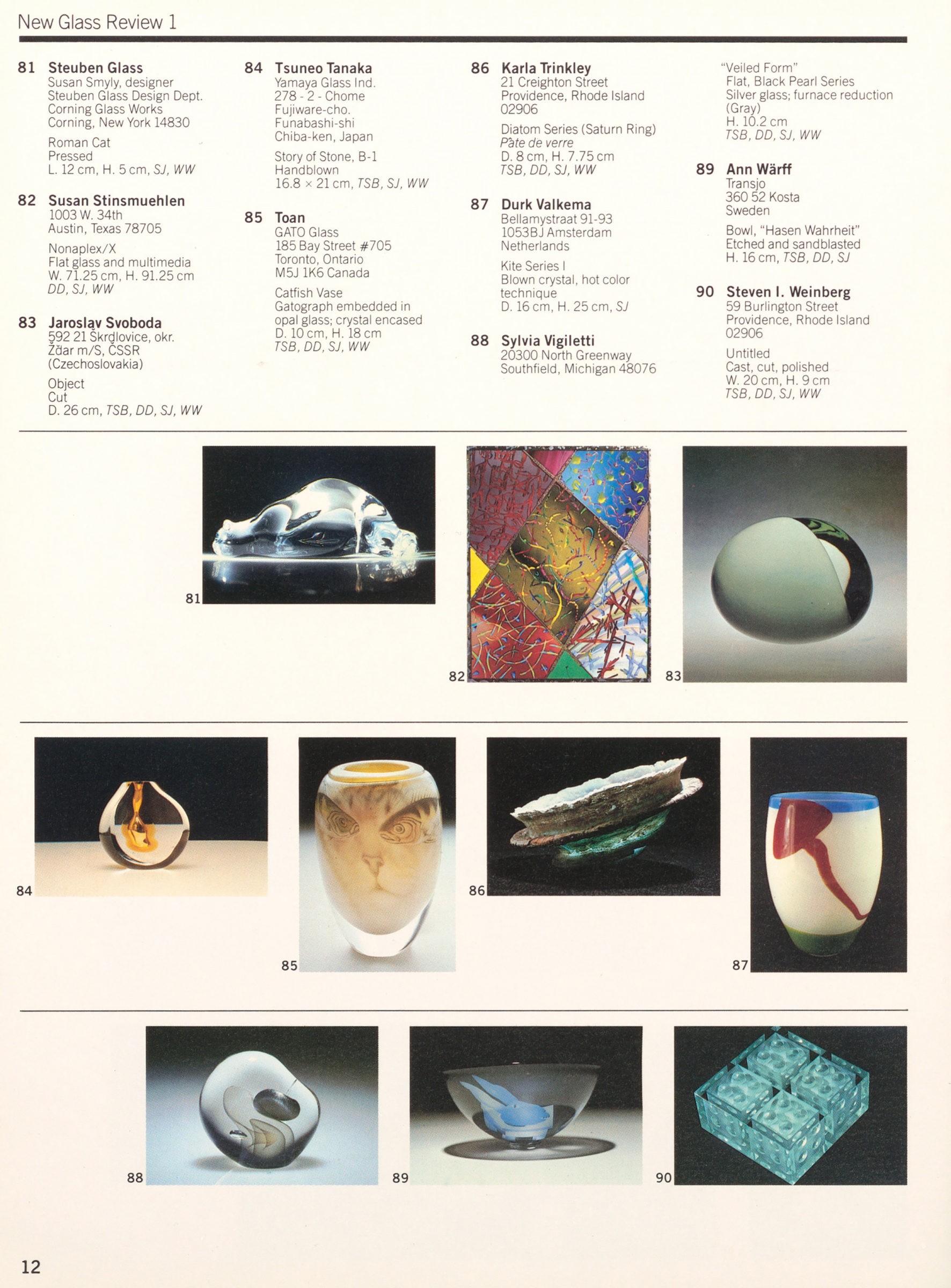

New Glass Review

In 1980, to maintain the momentum generated by New Glass: A Worldwide Survey (1979), the Corning Museum launched a new journal titled New Glass Review. Published annually, it has served ever since as an exhibition in print, documenting one hundred new works in glass produced during the previous year by artists, craftspeople, and designers around the world. Following an open call for submissions, panels of selectors choose the pieces to be showcased in the journal. Discussions about such a publication had been underway since 1975, when Thomas Buechner, the museum’s founding director and by then the president of Corning’s Steuben Glass division, introduced the idea. New Glass 79 provided the perfect opportunity to begin the initiative. Museum curators with expertise in modern and contemporary glass, including William Warmus, Susanne Frantz, Tina Oldknow, and Susie Silbert, have solicited panelists, chaired the selection process, and edited the publication. Buechner himself participated in the selection process for two decades.

Cover. New Glass Review 1 (1980). Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 37677).

New Glass Review 1 (1980), p. 13. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 37677).

New Glass Review 1 (1980), p. 12. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 37677).

New Glass Now (2019)

In 2019, The Corning Museum of Glass marked six decades of support for contemporary glass with New Glass Now. The exhibition, organized by Susie Silbert, Corning’s Curator of Modern and Contemporary Glass since 2016, showcased work by a new generation of glass artists and designers. Silbert employed the same selection process used in the museum’s two previous exhibitions, appointing a panel of evaluators to choose work following a global open call for submissions. Aric Chen, then curator of Hong Kong’s M+ museum; Susanne Jøker Johnsen, exhibitions head at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts; American artist Beth Lipman; and Silbert herself together selected contemporary works by one hundred artists representing thirty-two nationalities and more than twenty-five countries. Many of the glass objects, installations, videos, and performances presented in the show addressed complex cultural issues, such as sexual identity, gender inequality, and environmental degradation. An accompanying exhibit, New Glass Now: Context, curated by Silbert with Colleen McFarland Rademaker, Associate Librarian for Special Collections at Corning’s Rakow Research Library, highlighted the history of all three exhibitions. The fortieth-anniversary issue of New Glass Review doubled as the New Glass Now exhibition catalogue.

New Glass Now (May 12, 2019-January 5, 2020), Installation view, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Tamás Ábel, Colour Therapy: Washington, D.C. + Budapest, Exhibited in New Glass Now (May 12, 2019-January 5, 2020, 2019). Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (2019.7.8).

Susie Silbert talks about Thomas Buechner’s Corning ‘79 “New Glass method” of selectors.

2:37 Transcript

New Glass Now | Context (May 12, 2019-June 1, 2020), Installation view, The Rakow Research Library at The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

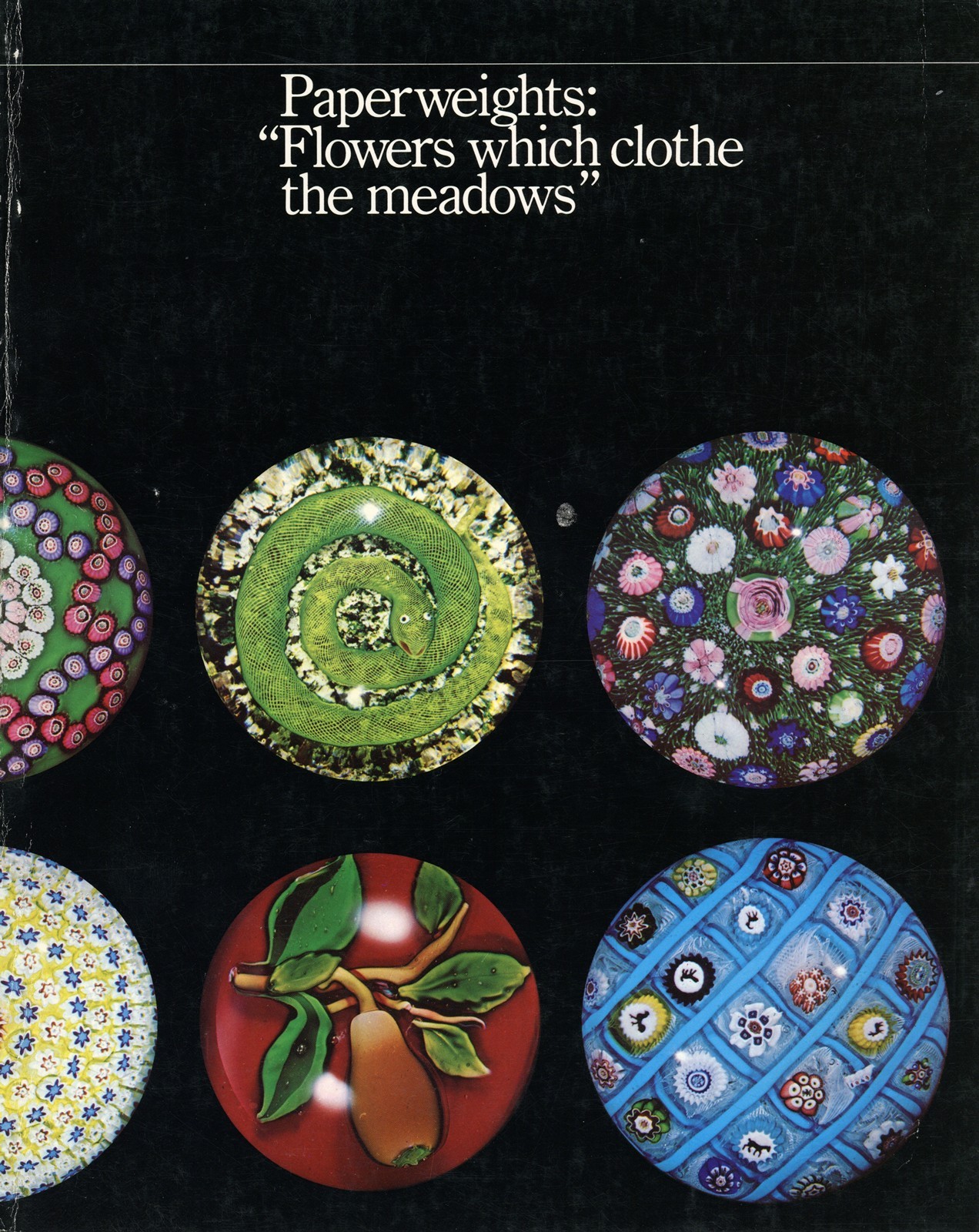

The Great Paperweight Show

In the mid-1970s, Dwight Lanmon, then chief curator at The Corning Museum of Glass, invited Paul Hollister to co-curate an exhibition of nineteenth-century paperweights. The Great Paperweight Show, on view at the Corning Museum April 29–October 21, 1978, featured 375 nineteenth-century weights showcasing “perfect technology and breathtaking design,”3 together with twenty-nine contemporary weights and related objects. Lanmon and Hollister also authored the accompanying 167-page exhibition catalogue, Paperweights: “Flowers Which Clothe the Meadows.” The title echoes Renaissance-era wonder over the Venetian colored glass cane technique known as millefiori, expressed in Italian historian Marcantonio Sabellico’s fifteenth-century invitation to “consider to whom did it first occur to include in a little ball all the sorts of flowers which clothe the meadows in the spring.”4 A catalogue supplement featured the contemporary examples, including pieces by established paperweight makers Paul Stankard and Debbie Tarsitano, as well as artists not primarily associated with the form, such as Richard Ritter and Tom Patti.

3Dwight Lanmon in conversation with Catherine Whalen, August 5, 2019.

4Paul M. Hollister and Dwight P. Lanmon, Paperweights: “Flowers Which Clothe the Meadows.” (Corning, N.Y.: Corning Museum of Glass, 1978), p.13.

Paperweights: “Flowers Which Clothe the Meadows“ (1978) exhibition catalogue for The Great Paperweight Show. Image courtesy of The Rakow Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 20097).

Detail of Millefiori Vase, Cristallerie de Clichy; manufacturer, 1845-1850. Overall H: 29 cm, Diam (max): 17.9 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of Jane and Jack Sexton. (2011.3.139).

Millefiori Vase, Cristallerie de Clichy; manufacturer, 1845-1850. Overall H: 29 cm, Diam (max): 17.9 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of Jane and Jack Sexton. (2011.3.139).

Paul Hollister and Dwight Lanmon Lectures, May 17, 1986.

Paul Hollister and Dwight Lanmon give lectures on paperweights for Wheaton Village (later Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center).

(Rakow title: Wheaton [sound recording] / Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 167926)

“Paperweights and Related Objects Included in ‘The Great Paperweight Show,’ Not Listed in the Catalogue.” Corning, NY: Corning Museum of Glass, 1978.

“The Great Paperweight Show at Corning.” Collector Editions 6, no. 3 (Summer 1978): pp. 28-29.

The Great Paperweight Show (April 29-October 21, 1978), Installation view, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

The Great Paperweight Show (April 29-October 21, 1978), Installation view, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

“At Corning [Paul Hollister] worked with Dwight Lanmon. [Hollister] was a major contributor in the aesthetics. I’m sure Dwight would agree that he contributed in no small way to that exhibition at Corning, which turned out to be the most-attended exhibition in the museum’s exhibit history up until that point. [Many] people attend[ed] the seminar, much more than any other seminar. It was huge—very, very popular.”

Paul Stankard talks about Paul Hollister working with Dwight Lanmon on Paperweights: “Flowers which clothe the meadows.”

01:27 Transcript

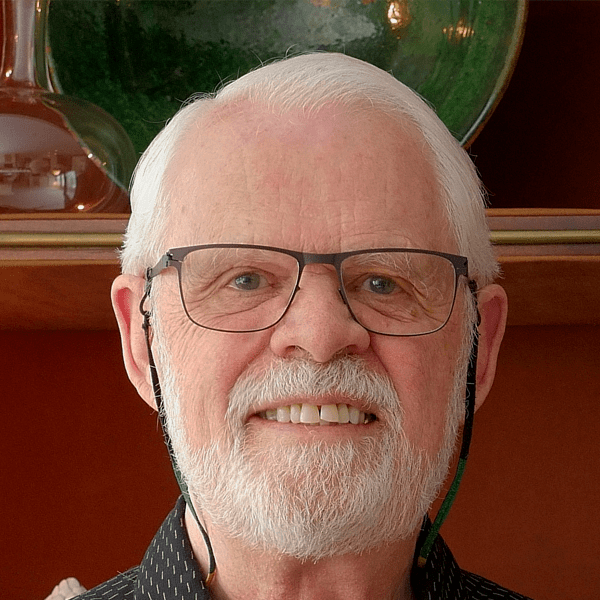

Dwight Lanmon discusses his and Paul Hollister’s work on selecting paperweights for The Great Paperweight Show, contemporary weights in the exhibition, and the accompanying Corning Seminar.

Rethinking Paperweights

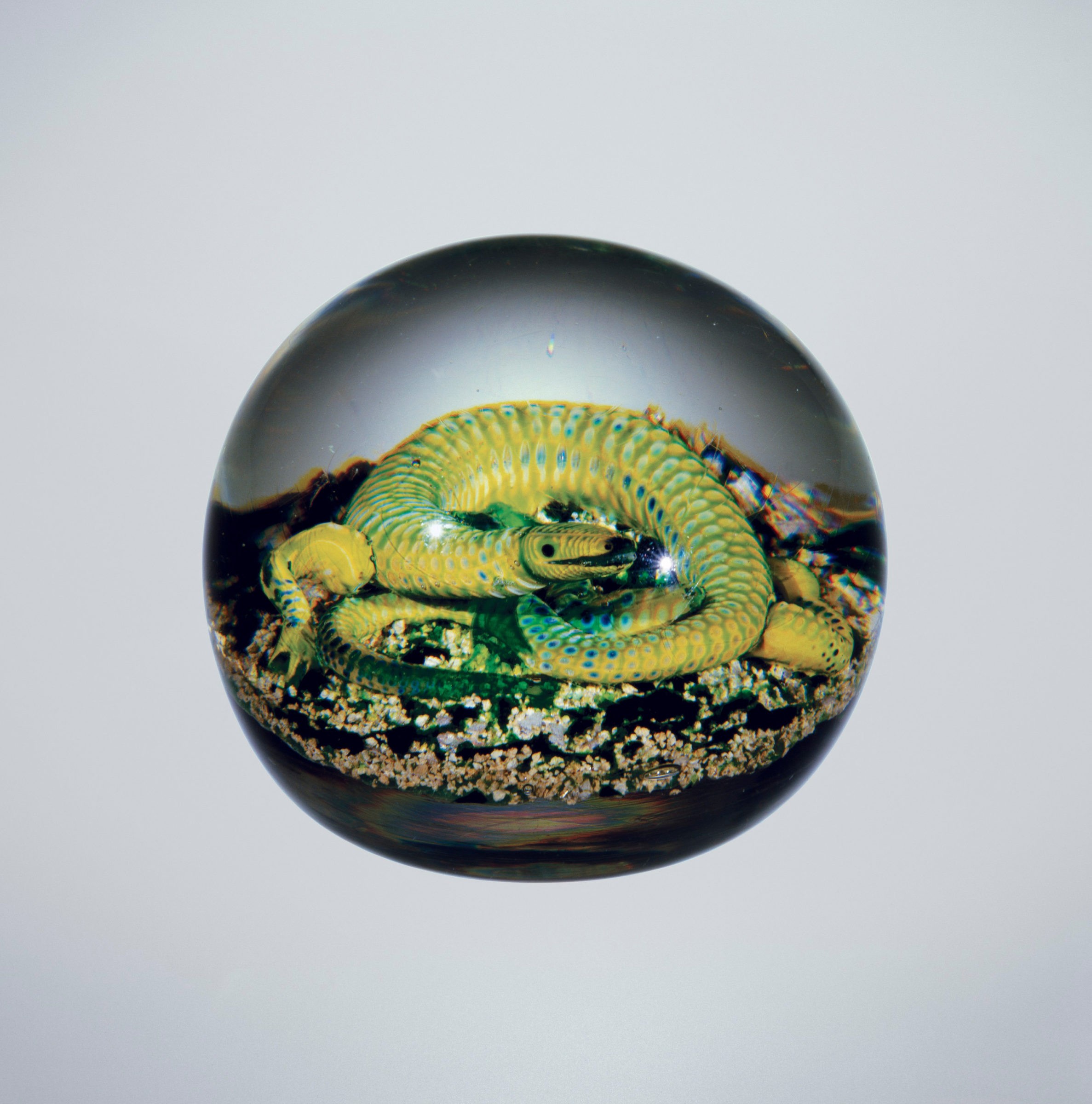

The Great Paperweight Show generated new scholarship and methods of documenting weights. Lanmon, with a background in physics, used ultraviolet light to determine the density of the paperweights in the exhibition—something never before done with weights. After the catalogue was published, Lanmon, on a trip to Paris to return objects borrowed for the exhibition, discovered that the lifelike lizard paperweights featured in the show had been made at the Cristallerie de Pantin. Paperweight maker Victor Trabucco, a consultant to Lanmon, later created his own versions of these mysterious weights.

The Houghton Salamander, probably Cristallerie de Pantin; manufacturer, 1878. Glass paperweight. Overall H: 8.8 cm, Diam (max): 11.5 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of the Honorable and Mrs. Amory Houghton. (55.3.79).

Victor Trabucco, Super Magnum Lizard, 2001. Glass paperweight. Diam: 5 in. Image courtesy of Victor Trabucco.

“And then in 1990, I was the first one to make the lizard. And that was one of the mysteries of lampworking. The two big mysteries for lampworkers were the Pantin lizard and the Blaschka flowers [Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, Harvard University]. Actually, I kind of picked up where they left off because I’ve improved some of the techniques that they use in making that lizard weight. And that was in 1990, and then just recently I just started making those Blaschka-type flowers, and I think I’ve discovered the technique that they really used to create those.”

Victor Trabucco speaks about Dwight Lanmon consulting with him on antique paperweight-making techniques and Lanmon’s discovery of Pantin as the maker of lizard paperweights.

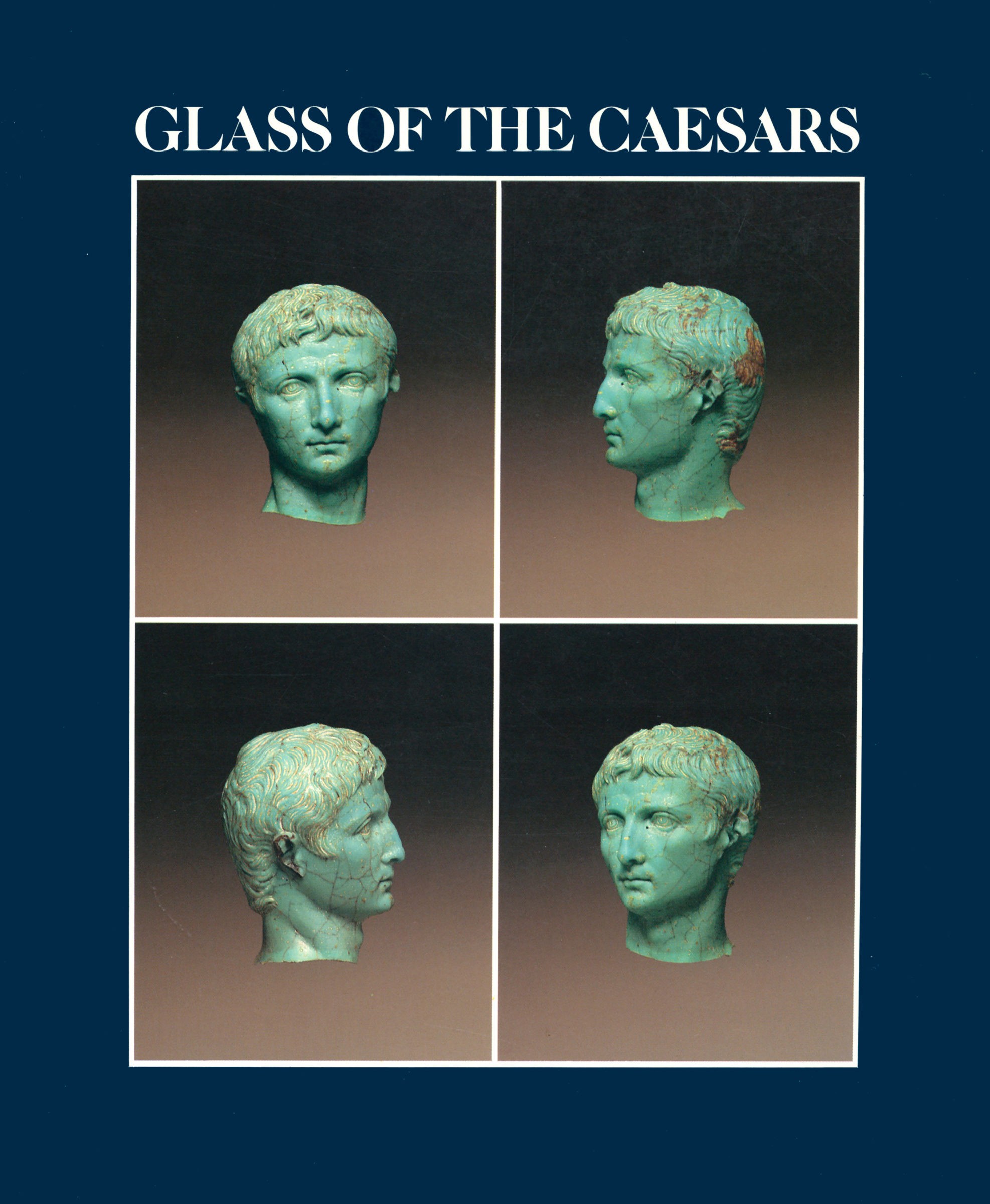

02:41 TranscriptGlass of the Caesars

Cover. Glass of the Caesars (1987) exhibition catalogue. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 31831).

In April 1987, The Corning Museum of Glass debuted Glass of the Caesars, an exhibition of 161 objects—from cups and bowls to lamps and figures—representing the primary types of glass and glassworking techniques used in the Roman Empire between about 100 BC and AD 500. Accompanied by a 340-page catalogue of the same name, the show was jointly organized by The Corning Museum, the British Museum in London, and the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Cologne, Germany. It traveled to London, Cologne, and the Museo Capitolino in Rome after closing at Corning in October 1987. Glass of the Caesars was a landmark exhibition that influenced artists, curators, and researchers for years to come; a two-day symposium at the British Museum in 2017 marked the show’s thirtieth anniversary.

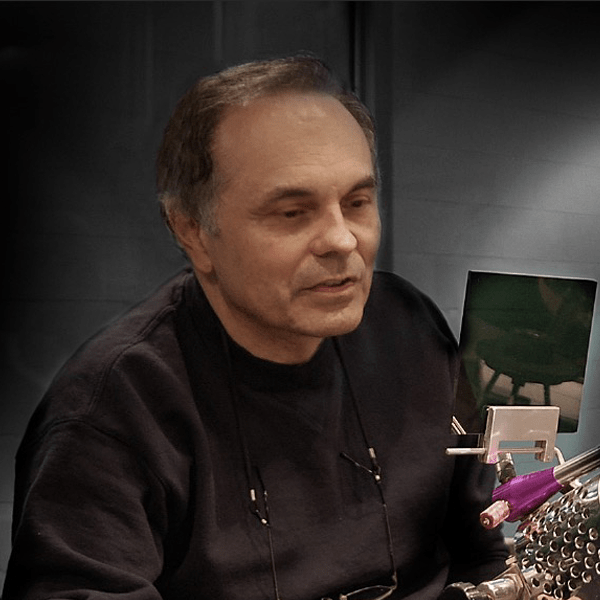

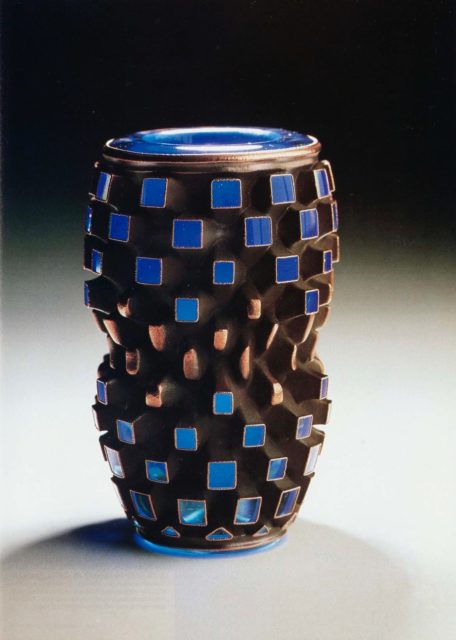

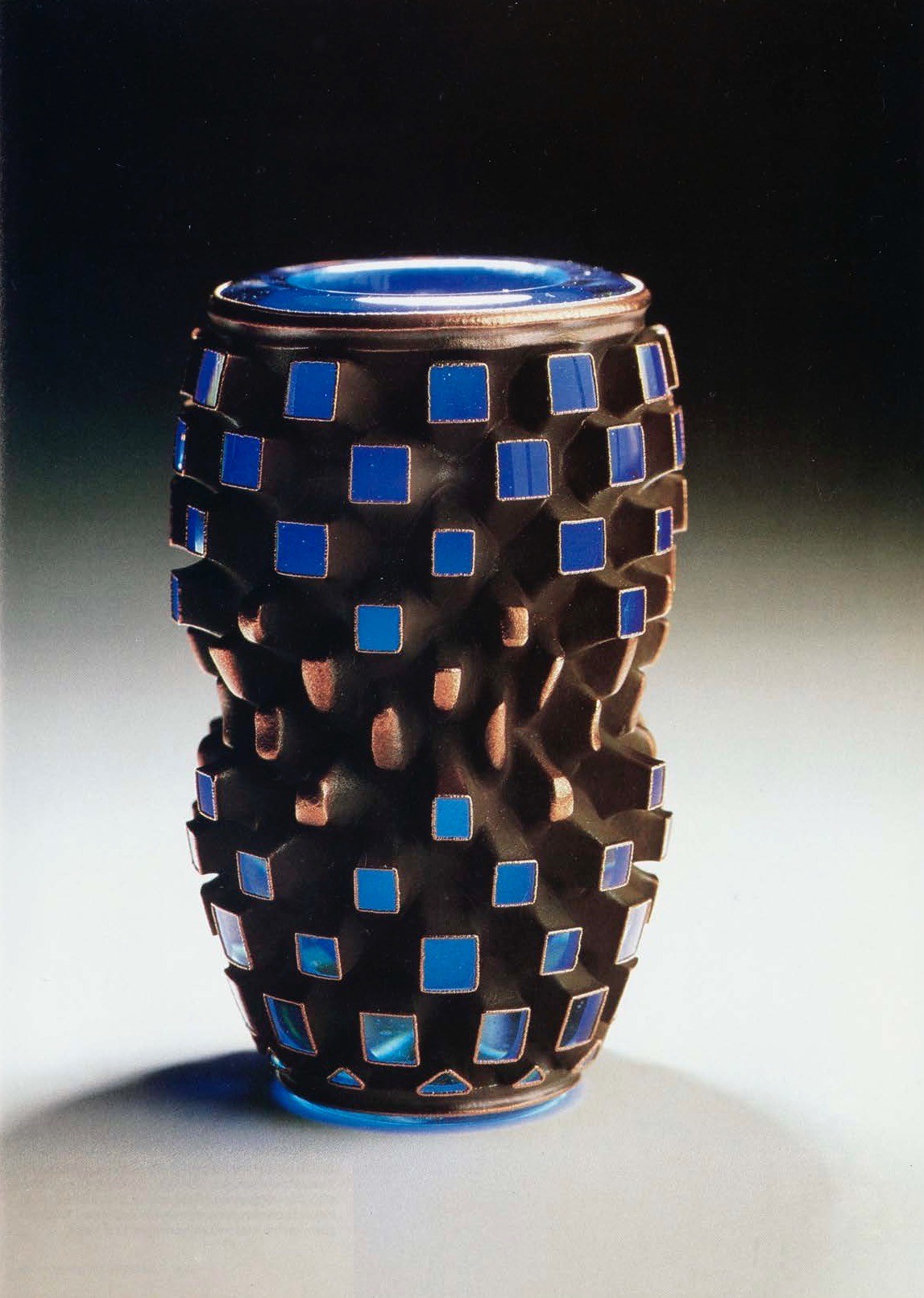

Several studio glass artists found the exhibition especially influential. Dan Dailey and Lino Tagliapietra’s collaborative series Dailey/Tagliapietra was directly inspired by the show. Dailey found the spontaneity and looseness of the objects fascinating, and he recalls poring over the exhibition catalogue with Tagliapietra. Michael Glancy was similarly taken with Glass of the Caesars and remembers Paul Hollister introducing him to ancient glass in Hollister’s home library five years before the show opened. Hollister wrote several feature articles on Glancy and compared the artist’s glass forms to Sasanian and Persian vessels.

“The Sasanian pieces were just a gong, you know, and Paul shared that with me. That was terrific.”

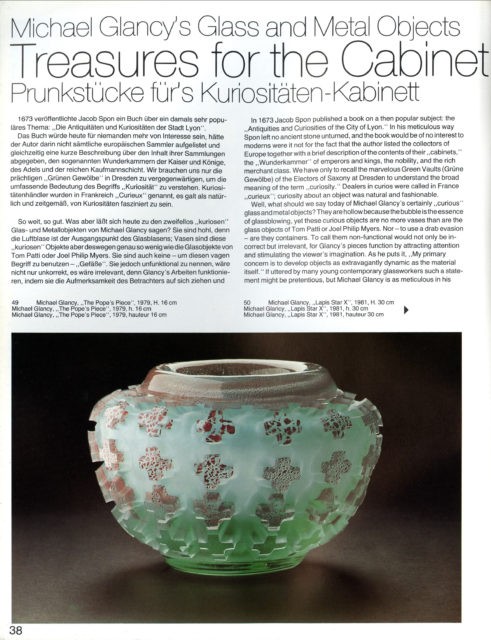

“Michael Glancy’s Glass and Metal Objects: Prunkstücke fürs Kuriositäten-Kabinett / Treasures for the Cabinet of Curiosities.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1982): 38–44.

“The Matrix Transformed.” American Craft 42, no. 4 (August/September 1982): 24–27.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/16745/rec/223

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol42No04_Aug1982

Michael Glancy’s Glass and Metal Objects: Treasures for the Cabinet of Curiosities/Prunkstücke für’s Kuriositäten-Kabinett.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1982): p 38.

“The Matrix Transformed.” American Craft 42, no. 4 (August/September 1982): p. 26.

Glass of the Caesars (April 24-October 15, 1987), Installation view, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

“…five years later, in 1987, was the Glass of the Caesars show at The Corning Museum. I was enamored with diatreta vases, Roman cage cup pieces, and this show, Glass of the Caesars, brought together, I think 13 of these pieces from all over the world. And these pieces had never been seen together–ever–until this exhibition, and that motivated me to spend countless hours working on a single piece. I mean, there are times when I think–you have to be very careful not to work just to work; you have to work towards a goal. And you can always overwork a piece, and it goes from getting better and better and better to a certain point, and then it’ll get worse, and so you have to stop at some point. But the diatreta and the cage cup pieces really inspired me. And then I saw this piece from Pompeii, a faceted beaker that I consider to be proportionally one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen, and to this day remains a reference for me for perfection and for my own goal of trying to reach a certain level of perfection, which is unattainable. Therefore we go for it, you know?”

Glass of the Caesars (April 24-October 15, 1987), Installation view, Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Michael Glancy discusses Paul Hollister’s article on Glancy in which he compares Glancy’s work to “Sasanian and Islamic wheel-cut Persian vessels.”

02:01 TranscriptMichael Glancy talks about Paul Hollister teaching him to make connections to his own work through ancient glass.

01:00 TranscriptThe Corning Museum of Glass: 21st Century

The Corning Museum of Glass has continued to thrive and expand over the last two decades. Renovation projects in 2001 and 2015 added more space for research, exhibitions, public programs, and retail. The expanded facilities include an award-winning Innovation Center, where hands-on interactive displays focus on glass science and technology, and a 26,000-square-foot Contemporary Art + Design Wing dedicated to presenting contemporary art in glass. The museum has created new artist residencies as well, with programs that support increasing diversity among glass artists and encourage the use of Corning’s historical research collections and specialty glass materials. A trailer truck outfitted as a mobile hot shop has enabled the museum to take glassmaking to parks and museums around the country, engaging new audiences in the art of glass.

Glassblowing Demonstration, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Vessels Gallery in The Innovation Center, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Contemporary Art + Design Galleries, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Mobile Hot Shop, The Corning Museum of Glass. Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.