Richard Ritter discusses experimentation with color mixing and progression in his work in a 1979 interview with Paul Hollister. Interview with Richard Ritter by Paul Hollister, June 9, 1979. (Rakow title: Richard Ritter interview [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168413). Clip length: 07:52. [note: June 9 date stated by Paul Hollister and Richard Ritter at beginning of recording]

Time stamp: 00:00

Clip 1: Paul Hollister asks Richard Ritter about his inspirations. Clip length: 02:31.

Paul Hollister (PH): Talking with Richard Ritter about God knows what. What is today? June— 9th—

Richard Ritter (RR): 9th. Right.

PH: —1979. Shall I ask you a question?

RR: I think that would probably be a good beginning—

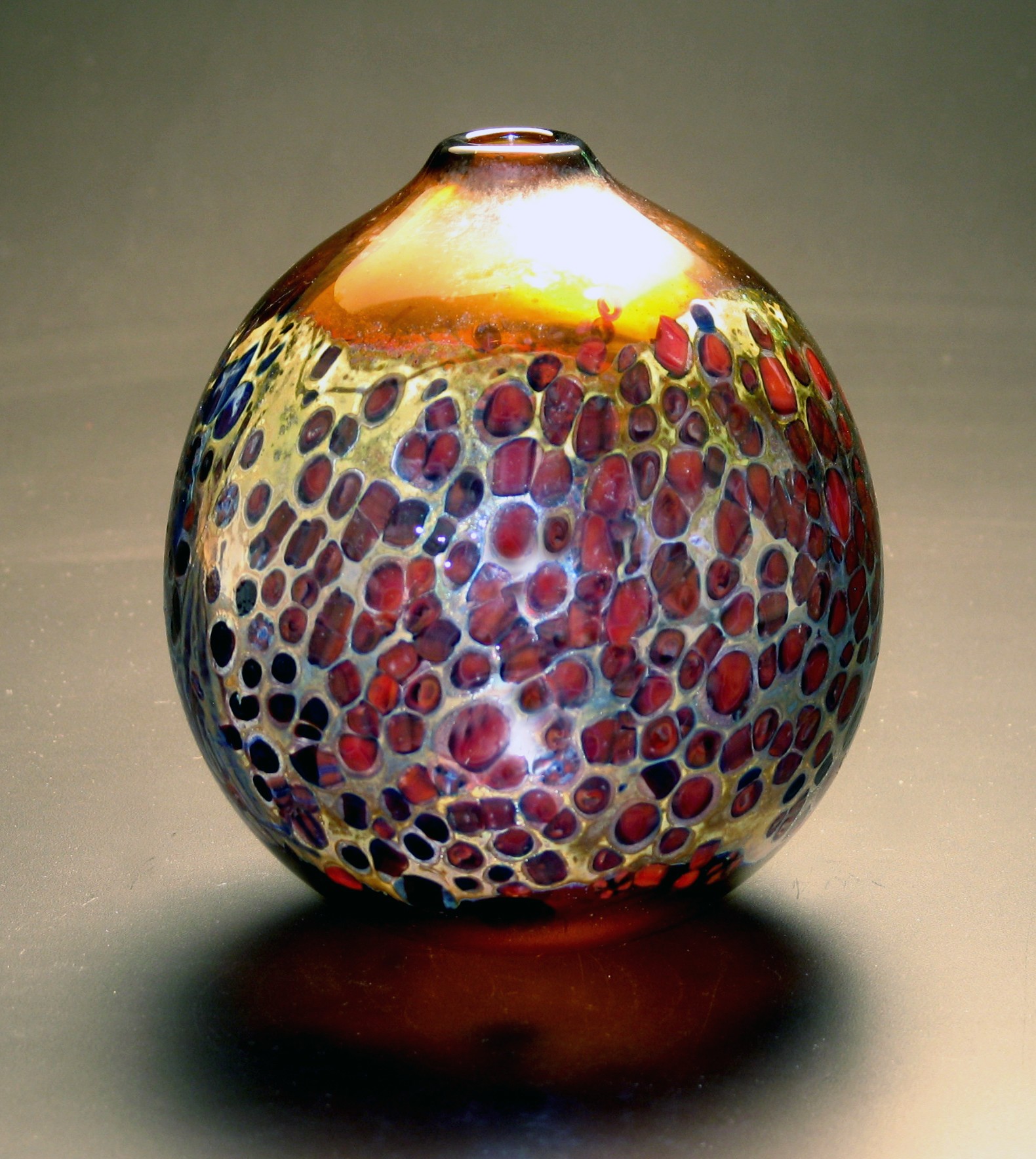

PH: Those squid-like, oyster-like, undersea octopus-like motifs inside your thick vases, are they inspired by anything in nature or are they just part of the process of moving the glass around and—?

RR: I think they’re more part of the process than, you know, taken literally anyway from anything.

PH: Hmm. Because they were—

RR: I like things that are organic, you know, and fluid and—but, in that—I mean it’s, you know, with glass, its fluidity is real important and I think that this carries it through. But they’re not inspired by the sea.

PH: But they have a very strong personality of—something of you in them, I mean, they don’t look like the next person’s at all.

RR: I hope not. [sound as of fingers drumming]

PH: But there’s a sort of a felt quality as if they were made of pieces of felt, in some of them, particularly the pearly gray ones I’m thinking of. And the off-whites, that is, it’s an almost matte finish feeling that you get. I know near where my studio used to be, out in the street there were all sorts of small manufacturers and they would throw out the, what was left after fabrics and things and leather and so forth were stamped out, what remained was thrown out and what remained was much more interesting than what they made because it was all these marvelous shapes and strips where, well, let’s say the tongue of a shoe, for example, got stamped out—

RR: Mm-hmm.

PH: —what was left was a wonderful pattern—

RR: Right.

PH: —of leather. What they couldn’t use. And your stuff reminds me of those remnants of what’s left from industrial stampings—

Time stamp: 02:32

Clip 2: Ritter Ritter talks with Paul Hollister about experimenting with color. Clip length: 01:49.

Paul Hollister (PH): Yeah. Where do you get a gray like that? I mean, that’s a very unusual gray.

Richard Ritter (RR): [laughs] I think, well, something I would have liked to have stressed in my talk is that by experimentation and trying lots of different things you come across a lot more than you’re looking for.

PH: Mm-hmm.

RR: And, you know, in other words, that gray came from trying to make a green.

PH: Hmm.

RR: If I had read enough, which a lot of people do, I probably wouldn’t have made that green, or that gray. ‘Cause that gray came by mixing two colors that glass people don’t put together. And that’s taking a cadmium and a copper—

PH: A cadmium red—

RR: Right, take a cadmium or selenium—

PH: Mm-hmm.

RR: Cadmium yellow. Taking cadmium, just a basic—the oxide of cadmium, and the oxide of copper, or carbonate. And I mixed the two together thinking I would get a green, and I got a gray because, now that I know, the metals interact. If you put two side by side, a blue, and a yellow, you’ll get a nice brown-gray line. If you mix the two together to start with you’ll get a gray to start with.

PH: Hmm, you won’t get mix—get a green by mixing those things?

RR: No.

PH: In other words, the green comes from something that’s going to be green like copper—

RR: Well, if you want a green, the way—and the way I do get my greens, is—I don’t use the chrome that most people use. My greens are different because, and Mark [Peiser] uses the same green, and that’s to mix cobalt with a cadmium; there isn’t that problem.

PH: Hmm.

RR: That you have with the copper.

Time stamp: 04:25

Clip 3: Paul Holliser comments on Richard Ritter’s strong color sense. Clip length: 03:27.

Paul Hollister (PH): As long as we don’t just make the mistakes—continue making the mistakes—

Richard Ritter (RR): Mm-hmm.

PH: —but use them, turn them to our own use. But then you will come out with a beautiful egg yolk yellow, or a brilliant vermilion. Looking almost like flayed flesh, or a wonderful soft robin’s egg blue. Almost, God forbid, baby blue [RR laughs], but you have an excellent color sense because you—you put ‘em together and yet you keep them—you keep control of them. They don’t—they don’t just run riot around there. Even the ones where you have a lot of—if you’ll pardon the expression—millefiori canes in them, they still—that little one that you had, that little vase you had, while back at Habatat on the National. [possibly Habatat Gallery’s annual national (now international) invitational glass exhibition], There were a lot of colors in there and yet they all harmonize; they all fit together. And you somehow manage to either keep the thing in the same key where you’ll have a white and a yellow and a blue together and maybe a little red. They’ll fit, but if you added a green it would be a mess, and you don’t. Apparently you understand where the, how far you can go and—in high-key colors, or when you have to keep it all muted and so forth. And I find that fascinating about your vases and also that layering, that wanting to get inside. It’s like a relief map, where the contours are—

RR: Mm-hmm.

PH: —are drawn on the top of the hill and then the next layer down and then ten feet below that and so forth. And they’re these pockets, and you want to sort of slide in underneath. It’s almost like underwater coral formations where you want to dive down, and it’s very [Jacques] Cousteau, your things.

RR: One of the things I would—do, too, and drives some people—some of the people that work with me just—apprentices wonder what I’m doing. I’ll do a lot of work on the first layer and then cover it—

PH: Hmm.

RR: —only leaving you a little bit to see.

PH: Mm-hmm.

RR: And really there’s a tremendous amount of work in it, but, as you say, peeking into it is—it’s half of a—half of the piece.

PH: Yeah.

RR: And—I really work—it’s very hard for me to get into explaining to people why or what for, or—because I really function for myself or an intellectual vein or whatever you want to call it because I’m not—on instinct.

PH: Hmm.

RR: I’m sure it’s all come from training along the way, and exposure—

PH: And you can’t worry about it while you’re doing it or—

RR: No.

PH: —you wouldn’t be doing it. You wouldn’t have time to worry about it.

RR: And I love to change, and I’m always thinking about what the next things I want to get into. And sometimes it gets me into trouble because [laughs], you know, it—it can be too far ahead of what I’m working at. And I can always tell when I’m done with it that I was thinking about the next piece and not the piece that I was involved with.

PH: Yeah, yeah.RR: And that means it’s time for a change.

Permalink