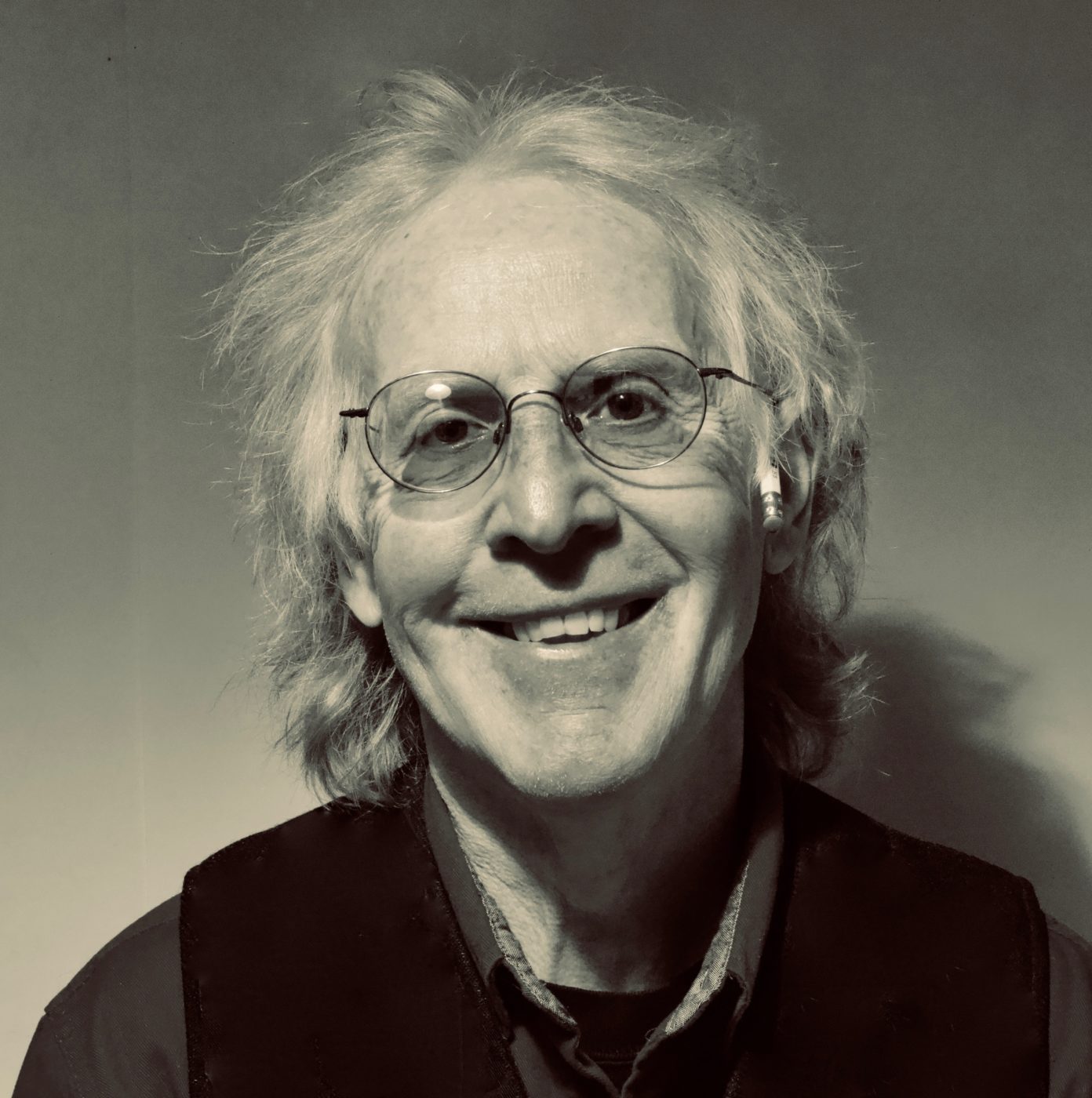

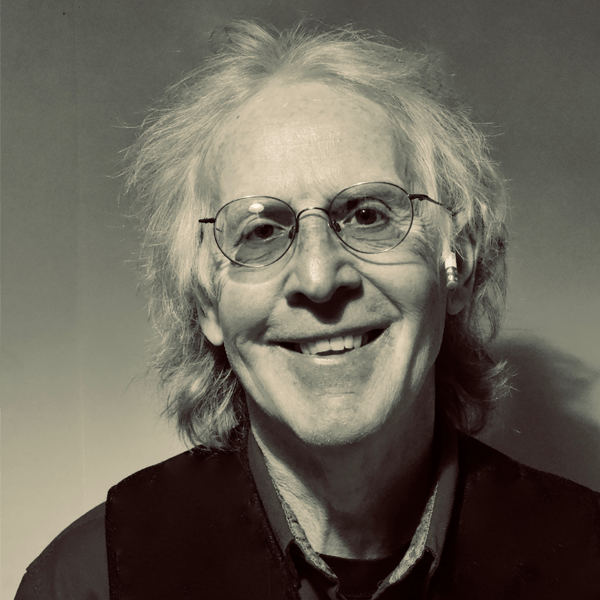

Image courtesy of Ken Carder.

Ken Carder

North Carolina–based artist Ken Carder (1955– ) studied art at Bowling Green State University before relocating to North Carolina to focus on glass in 1981. After working as an assistant to Harvey Littleton for three years, Carder was an artist-in-residence at the Penland School of Craft from 1984 to 1988, a position that helped launch his career as a full-time studio artist.

Works

Black and Blue Clown, 2016. Glass. H: 23.5 in, W:10 in, D: 6.5 in. Image courtesy of Ken Carder.

New Taboo Front View, 2012. Glass. H: 23.0 in, W: 11.5 in, D: 9 in. Image courtesy of Ken Carder.

New Taboo Back View, 2012. Glass. H: 23 in, W: 11.5 in, D: 9 in. Image courtesy of Ken Carder.

Ken Carder discusses the high concentration of glass artists at Penland and in the surrounding area.

01:00 TranscriptKen Carder talks about William and Sally Worcester’s role in Penland’s flameworking workshop.

00:37 TranscriptKen Carder talks about the paperweight set-up Stankard demonstrated in his flameworking workshop.

01:30 TranscriptKen Carder discusses the image [above] showing a cylinder that came out of a paperweight mold during the flameworking workshop.

00:30 TranscriptGlass artist Ken Carder discusses the importance of the Penland School of Craft as an “environmental utopia.”

01:55 TranscriptKen Carder discusses the importance of Bill Brown’s artists’ residency program at Penland.

02:36 Transcript