Image courtesy of Douglas Heller.

Douglas Heller

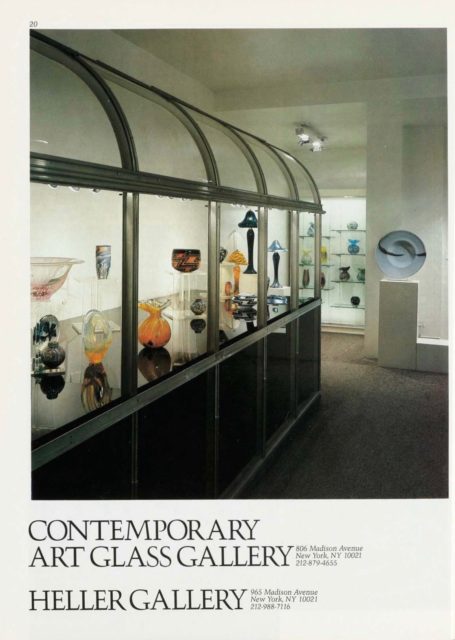

Douglas Heller (1946– ) is a co-owner of the Heller Gallery, a New York City art gallery focused on contemporary glass sculpture that he currently runs with his wife, Katya Heller, and his brother Michael Heller. Heller cofounded the gallery, originally named the Contemporary Art Glass Group, with Joshua Rosenblatt in 1973. Heller’s brother Michael replaced Rosenblatt as partner in 1979. Heller has organized hundreds of exhibitions and served as guest curator and juror for many other glass projects, including The Corning Museum of Glass’s New Glass Review. He is a founding board member of Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center’s Creative Glass Center of America (later Creative Glass Fellowship Program) and serves on UrbanGlass’s advisory board.

Media

Douglas Heller discusses the earliest days of his gallery.

1:35 TranscriptDouglas Heller discusses the earliest days of his gallery. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:34.

Douglas Heller: So I started with my first partner, regional partner, that was Joshua Rosenblatt, the son of Minna and Sidney Rosenblatt, great antique glass dealers. And they were actually the reason that I became involved in the field. They mentored me and inspired me. So we started in a shop, a tiny shop, that’s at the corner of 68th Street and Madison Avenue and that had been Minna Rosenblatt’s first permanent location and prior to that I think it was Leo Kaplan’s first location, so it had a history of glass specialists in there. The place was tiny. I mean the room we’re sitting in right now is the size of the entire shop, but it was a window in a great location, and part of this was a business strategy that focused on the idea of placement, you know, the old real estate location concept that that was considered the Carriage Trade finest neighborhood for fashion, for design, for most things. So if you were there, it meant in a sense that you were already vetted. So even if you were an unknown entity, as Joshua and I were at the time, we were in the right place at the right time and that helped and of course it helped enormously that Minna had vacated the shop that we took to move next door to a larger location and then there was this wonderful synergy.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about early artists at his gallery and the name “Contemporary Glass Group.”

1:47 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about early artists at his gallery and the name “Contemporary Glass Group.” Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:47.

Douglas Heller: We started to go around the country, going to street fairs and craft fairs. I mean there was a time, we went down to Florida when Mark Peiser was selling these exquisite little miniatures at a street fair, you know, and we would see people there. We would visit them in their studios and in their homes, and then we decided to put together this group of four that represented different styles. And that’s where the name came from Contemporary Art Glass Group. And it also somehow implied something greater than just the two of us. When Josh and I went down to the city to register the name and to create the business, we were told two people do not comprise a group and we couldn’t register the name, and we pulled out our dictionaries and said. ‘No, “group” according to this definition two people can be interpreted as a group,’ and they told us no. So Josh and I went back and we each took our middle name. We put it on the forms. And that was the third member of the group and that we then became the Contemporary Art Glass Group and that’s how we picked the people. So it was a combination of the work they were doing and the individuals, you know. We wanted people who felt it was compatibility with because this whole thing we wanted it to be cooperative and in the beginning we purchased every piece because we were unknown to everybody and the artists had very little money, not that we had a lot, but we had more than they did, and we felt that this again was about establishing credibility. So we would buy it we own it. We would then be committed and we would have to sell it.

Permalink

Douglas Heller discusses Paul Hollister’s interest in Paul Stankard’s work.

00:44 TranscriptDoug Heller discusses Paul Hollister’s interest in Paul Stankard’s work. Oral history interview with Doug Heller by Barb Elam and Jesse Merandy, September 27, 2018, Heller Gallery. Clip length: 00:44.

Doug Heller: So there was that thing. Then you had people like Paul Stankard. Paul comes from a very different background than the academic world. You know, he’s a brilliant technician and somebody as an individual who is so genuine and in touch with his own feelings and the kind of spiritual aspect of what religion has to offer that he brought something very real to a traditional craft form—paperweight making—which, for the most part, was quite sterile. But Paul revolutionized the whole thing, and I think that’s what attracted Paul Hollister to Paul’s work. It was truly, quietly revolutionary.

Permalink

Douglas Heller describes the synergy between himself and Paul Hollister.

1:41 TranscriptDouglas Heller describes the synergy between himself and Paul Hollister. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:40.

Douglas Heller: Paul was a character extraordinaire, you know. I mean, he was obviously extremely knowledgeable, but he was also very quirky and both myself and my partner were very quirky. We were not like the antique dealers that we would meet at the show, they were also idiosyncratic people, but different, you know. So Josh was six foot four with a big beard, he was—he had been an art director at Ted Bates art agency, he followed the dictum of Tim Leary, and tuned in and dropped out, you know. And we were involved in a lot of interesting explorations during that time. I had long hair—not as crazy as Josh, you know, and beard—but we were not your usual Madison Avenue dealers and I’m sure they were people, who opened the door, took a peek in, and said: ‘Whoop, wrong place,’ you know, and went out. But Paul Hollister, while he looked very mainstream, conservative, sort of Ivy League, you know—he was conservatively dressed in tweed, always proper and clean-shaven and short hair, you know, and extremely erudite and knowledgeable, but he was, as I said, an extreme character, and I think there was a synergy and an attraction in the personalities. Yes, he was interested in glass and that was unusual, too. And then, you know, he was interested in history. So that made it an enriched relationship, it was a lot of fun because of that.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about Paul Hollister giving lectures theatrically.

1:00 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about Paul Hollister giving lectures theatrically. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 00:59.

Douglas Heller: …we were both speaking to a Glass Club, I forget where it was, might have been Connecticut, and Paul presented his talk first, and he was behind the podium, he was very conservatively, properly attired, and read and spoke very seriously. And after he finished each page, he would take it and throw it up in the air like that, but never cracking a smile. So it was this really, you know, premeditated, outrageous humor to it, but the talk was deeply rooted in scholarship, you know, so he would do anything to be the opposite of the “nerdy collector” or the “nerdy scholar.” He didn’t want to be seen as just a dry professor. So he was the outrageous professor. and it didn’t make everybody comfortable. You know, I was very comfortable with it, and we had this rapport with that.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about Paul Hollister’s eccentricity.

1:40 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about Paul Hollister’s eccentricity. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:40.

Douglas Heller: …he brought a lot to the table, but he was clearly uncomfortable in being pigeon-holed as just a certain person, you know, he wasn’t going to be the dry professor. We were up in Corning once at a Glass Art Society Convention, at the end of the conference they had a party, they always did, and Paul decided to make a costume that night. And he just made a costume out of—he took a t-shirt, turned it inside out, wore over his head so it looked like a nun’s habit, you know, and I was with another person who was very important to me in a mentorship role, Tom Bueckner, who was director of the Corning Museum of Glass when he was young—I think he was the youngest museum director in United States. He was director of the Brooklyn Museum, also an extraordinarily erudite man and talented painter, graduated, I think, from the Sorbonne. Tom was horrified, you know, he goes—he turned to me and says ‘Keep him in his room,’ you know. So we went to the party and had a good time and a lot of people had a better time because Paul was there. But he reveled in that, in not allowing people to be too comfortable. I think that was part of it. He liked to get under the skin, now nothing could seem to me more dry and conventional than to be a paperweight expert, you know. So I think he, you know, embellished who he was a bit or just reveled in who he really was, you know, in contradiction to your expectations of that.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about building his gallery’s reputation and marketing studio glass.

1:27 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about building his gallery’s reputation and marketing studio glass. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:26.

Douglas Heller: …the truth was we were meeting experienced collectors who had the eye and the experience to recognize really good work, even though it didn’t have the cachet of being established yet. So the question often was, ‘What is that?’ You know, they’d look at the artists we were representing, and the four people we decided to focus on were Mark Peiser, James Lundberg, Rolin Jahn and John Nygren. Each with a distinctly different style. The objects were small. They ranged from Jim Lundberg doing Neo-Nouveau work that was very reminiscent of Tiffany—of the blown glass, the iridescent glass, Tiffany and Loetz—and to Mark Peiser, who is still working today and of the four I think is the only one still working today. But, so the first question would come from people is well, ‘What is that, who made that? I’ve never seen that before.’ Then after we’d explain a bit about the work, then they would turn to us and go, ‘And who are you?’ you know, so it was establishing credibility and we found that by doing the shows that we got this widespread exposure, but it also let us appear and disappear for a while and then reappear, and people had the sense after they would see us two, three, perhaps four times that we knew what we were talking about and we were credible.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about studio glass expanding through university programs and Heller Gallery’s decision to move to SoHo.

1:58 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about studio glass expanding through university programs and Heller Gallery’s decision to move to SoHo. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:58.

Douglas Heller: …but in the interim, the field was changing, the artists were evolving dramatically, the work was changing. The focus from people like Mark Peiser and the earliest practitioners who, I think, saw themselves more in a kind of counterculture vein started to change to where the art schools now had established programs and it was becoming something much more mainstream. Harvey Littleton, who we had been representing, you know, was a great advocate and went out and barnstormed the country. By the time he was done, several universities and colleges had instituted glass programs, which proved to be enormously popular within the schools. So suddenly the type of work was changing. People were no longer just rediscovering the wheel, building their own furnace, making their own batch, you know. They were doing something that was far more sophisticated, and we felt challenged by that, and the gallery had to respond. And the message in New York, the area that was happening in, was in SoHo. That was the dynamic neighborhood where new things were happening, and the spaces were amazing in terms of scale compared to the uptown spaces. Uptown we always had to have a buzzer on the door, there was a certain elite Carriage Trade aspect to it, but now we went from the idea of, ‘Okay, we are feeling more established. We’ve built some credibility.’ Pieces from the gallery have been going into museums, ranging from MoMA’s design department and Metropolitan Museum of Art, of course, the Corning Museum of Glass and other institutions, I mentioned Walter Chrysler earlier, you know, and we said we want to do something that’s younger, more responsive, and reflective of what’s going on.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about working more with European artists after seeing the Corning ‘79 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

01:37 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about working more with European artists after seeing the Corning ‘79 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Oral history interview with Doug Heller by Barb Elam and Jesse Merandy, September 27, 2018, Heller Gallery. Clip length: 01:36.

Doug Heller: So we looked down in SoHo, and we found wonderful classic cast-iron space on Green Street, that was a photographer’s flea market. And we met a very interesting landlord who was open to something new because we still were something odd and didn’t have the type of credentials he was used to. And he was Peter Max’s uncle, and he liked the idea of something quirky; and we were definitely quirky, you know. So we took this space and that changed things considerably, this was suddenly from these small boutique spaces of 900 to maybe 1200 feet. We were in 3000 square feet with a 2700 square foot downstairs, half of which was finished, and we were holding different types of exhibitions. The work changed dramatically and also the range of artists that we represented changed. We started to work more with the Europeans after being exposed to this great landmark show from the Metropolitan Museum of Art called New Glass: A Worldwide Survey 1979, and I believe there were glassmakers from 60 different countries there. I went up to the opening of that show and truly had an epiphany after seeing the work that I didn’t know existed, you know, a level of sophistication, a level of scale. And I drove back from up state just transfixed with what we could do next.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about moving Heller Gallery to the Meatpacking District and then to Chelsea.

3:35 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about moving Heller Gallery to the Meatpacking District and then to Chelsea. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 03:35.

Douglas Heller: And then after 18 years in SoHo, the neighborhood changed dramatically and started to echo what had happened on Madison Avenue. It was filled with, you know, the uptown Carriage Trade businesses and it was losing the gallery identification and the thing that gave it its particular personality and, like many of the people, we started looking elsewhere. I was on the Gallery Association in the neighborhood and at each meeting somebody would say ‘Well, you know, I have to resign. I’m moving to Chelsea.’ So we did a similar thing to what we had done up on Madison Avenue. We had had another couple of years left on our lease and we went to the landlord and said, you know, ‘This place seemingly is worth a lot more money than we’re paying for it, now you could get different types of tenant.’ And indeed they got Vivienne Westwood, the doyenne of punk. She took our space and the landlord bought us out and we used that money to establish ourselves in what was the Meatpacking District before it was the little black dress, fabulous restaurant Meatpacking District. It was the big fat butcher with a blood-stained apron district and the 24-hour sextrade going on. But it was a fabulous location, we had met this wonderful landlord and we got a great space that was again two levels, it was as big as the SoHo space, we had 6,000 usable square feet, and slowly the neighborhood started to change from Dizzy Izzys to Stella McCartneys—Dizzy Izzy being a 24-hour bagel restaurant—to the Stella McCartney store and the rest. And we stayed there, I guess, for about 17 years also, but that neighborhood again started to change dramatically, and we felt a little bit out of place. Even though we loved the location, it was no longer a destination for galleries, and it had become completely—what should I say?—“retail” again. So we started looking and again we had chosen wisely, getting in a bit ahead of the curve in the value of the neighborhood. And we made another deal just a short time before our lease expired. And we, with the help of our previous landlord, found this location, which is again a handsome space. It’s 3,000 square feet. We lost all of our storage space. So that is the saga of our moves and we feel very comfortable here. It is truly one of New York’s major gallery neighborhoods. You now have the Lower East Side and Chelsea and we found—while we looked in both locations—we found the physical layout here much more to our liking. Downtown for the most part, the spaces are in small tenement buildings with smaller footprints and the rest, and given that I’m a lot older now and business is a lot more established, this felt like the more logical place to be.

Permalink

Douglas Heller discusses learning about a Czech artist through the Corning ‘79 show, whom he later represented.

01:03 TranscriptDouglas Heller discusses learning about a Czech artist through the Corning ‘79 show, whom he later represented. Oral history interview with Doug Heller by Barb Elam and Jesse Merandy, September 27, 2018, Heller Gallery. Clip length: 01:02.

Doug Heller: When I went to that show at Corning that I called New Glass 1979, the one that was an epiphany for me. There were objects in that show by Czech glassmaker, named Frantisek Vizner, who I later represented—just several of them came up in auction at Rago—that were very physical, bowl-like forms carved out of blocks of glass, that if you went to pick up must have weighed 18, 20 pounds. I mean, they were hefty things, very tangible, and yet he did something with the edges and with the surface treatments that made them seem to dissolve and merge into the space around them. So it—you couldn’t quite decipher where the physical ended and just space began, and they were to me sublime objects, you know, transcendent objects. And yet big and heavy, you know, so I can see wonder in physical things.

Permalink

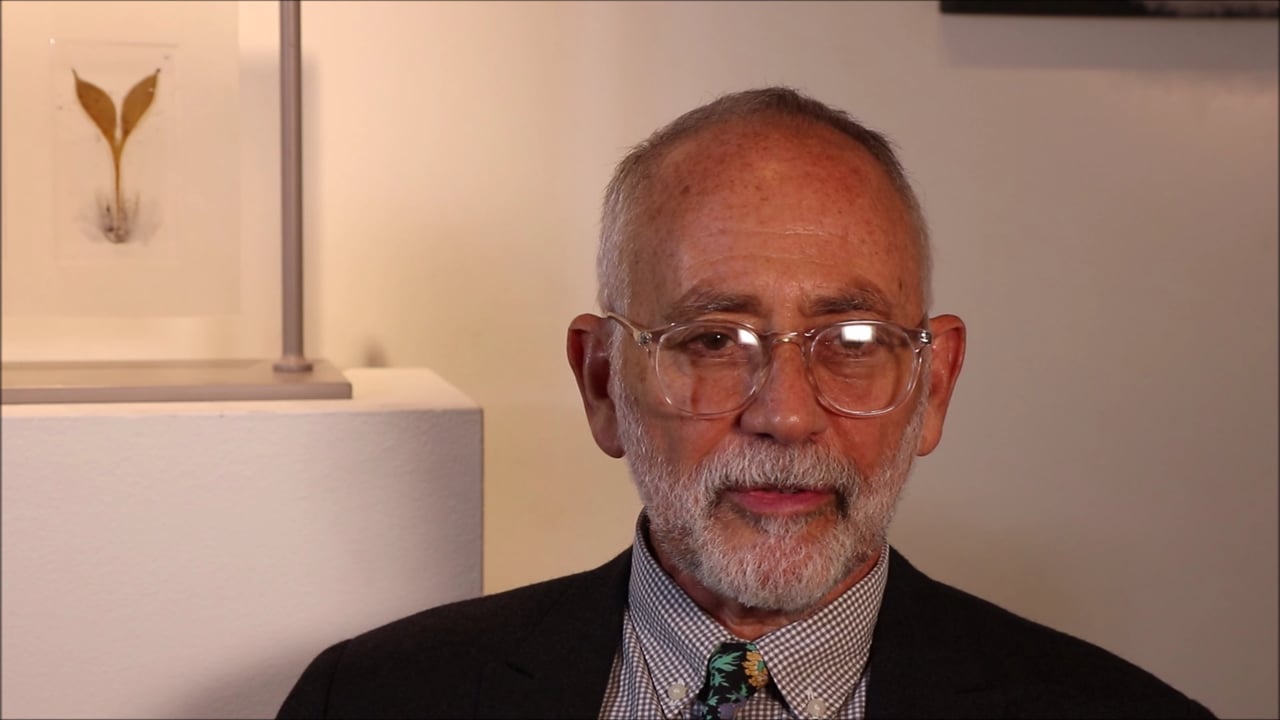

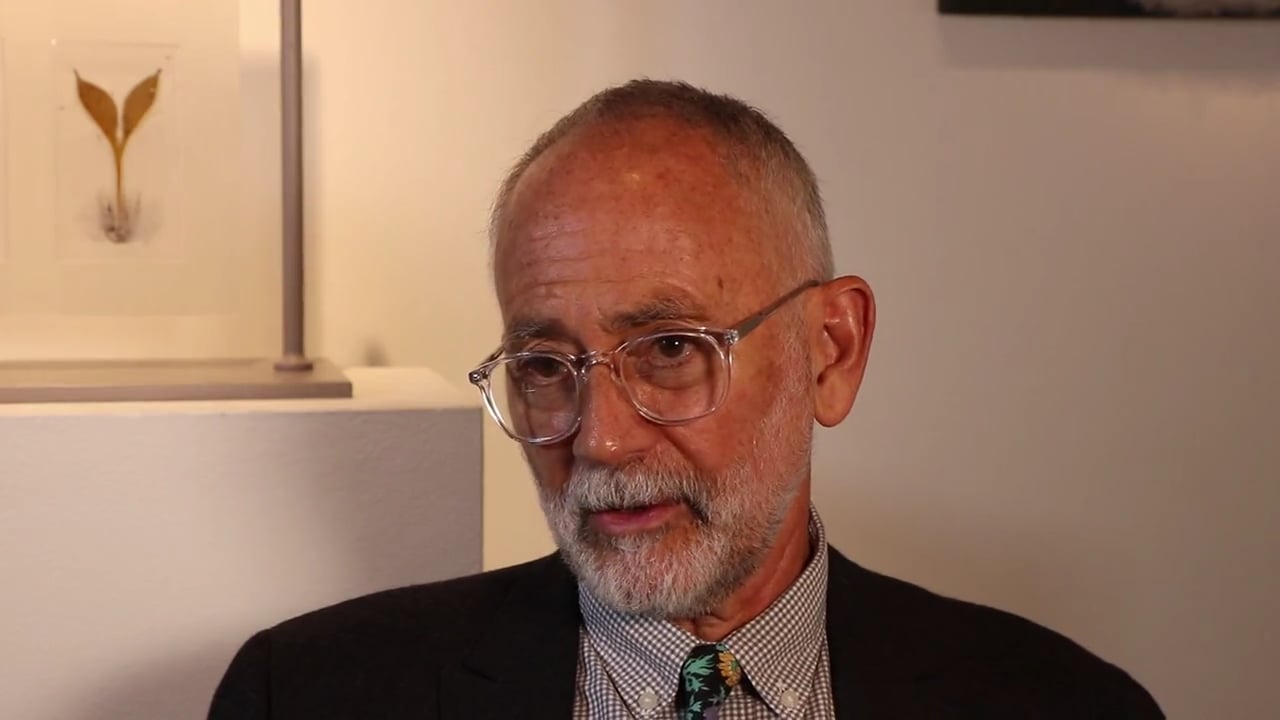

Douglas Heller discusses wearing Paul Hollister’s tie as a tribute to him.

0:56 TranscriptDouglas Heller discusses wearing Paul Hollister’s tie as a tribute to him. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 00:55.

Douglas Heller: The tie? The tie is a Liberty of London tie. This belonged to Paul Hollister and I always equate a Liberty tie or a pair of red socks or a very flashy lining of a conservative suit with a secret declaration by the person wearing it that there’s more than meets the eye here. I may be dressed in a very conservative manner, but something else is going on. So Paul had a collection of Liberty of London ties. And when he passed, Irene, very generously, went to friends and said, you know, ‘Paul would want you to have a tie, would you like to choose one?’ And when I go to certain events, I wear this tie, it’s a cherished possession of mine. Although, it’s completely antithetical to my usual style.

Jesse Marandy: Let’s zoom out, make sure we—

Mike Satalof: Great.

Barb Elam: Yeah, make sure we—

MS: Gotcha.

[inaudible, JM, BE, MS laugh]

JM: Gonna do a quick zoom out. There it is. That’s nice.

Permalink

Douglas Heller talks about Habatat Gallery.

2:46 TranscriptDouglas Heller talks about Habatat Gallery. Oral history interview with Douglas Heller, September 7, 2018, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 02:46.

Douglas Heller: we started independent of each other. Very different cities, very different places, and, I think, very different intents. I’ve always admired what they accomplished. Ferd Hampson was the founder along with Tom Boone, his brother-in-law at the time, and now his son Corey Hampson, who I must talk to every two weeks and we sometimes transact business together and I see them all the time. So it’s, it’s as different as—I’m Manhattan born and bred, you know, I’m a product of New York City, pure product of New York City. They’re from a very different environment, you know. We’ve both found the same thing, but I think in different ways, and they’re after 45, 46 years, they’re in business and we’re in business. A lot of other people have come and go. So they’re the other great experts in it, but, you know, as people as in what and how we do it, I think we’ve gone in different directions. And one of the things that they’ve like to do and it’s in most of their advertising, it’s always the biggest glass show in the world. And we were doing some of that for a long time when we had the Glass America shows—first one called Contemporary Art Glass 1976, then it morphed into a title called Glass America—that show would have 60 people or so. And we did that for a number of years and the idea was it was a crash course introductory survey in studio glass and you would be immersed in all the possibilities. But then at a certain point we said we’ve done that and now we want to zero in on certain channels, threads, trends that we find interesting, and our pursuit is what is interesting to us, not what can we sell—although, we have to sell to stay in business and if we can’t sell this work, these people can’t maintain their practice either—but we’ve taken a different approach. We represent far, far fewer—we see lists of—gallery lists of artists they represent. Sometimes we are befuddled by how many names there are compared to what we know it takes to represent somebody, you know, to understand the work, have a dialogue with the person, find the type of audiences, create the relationship I was talking about earlier, you know, seeking out proper venues for the work. But Habatat is, I think, flourishing and that is a great achievement in itself and its second generation.

Permalink

Susie Silbert discusses the importance of the Heller Gallery’s Glass America shows.

1:38 TranscriptSusie Silbert discusses the importance of the Heller Gallery’s Glass America shows. Oral history interview with Susie Silbert by Catherine Whalen, February 25, 2020, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:37.

Susie Silbert: The Glass America shows that Heller Gallery [New York, New York] did when it was still called the Contemporary Art Glass Group in 1976 and 1978, were really important national surveys of glass that tried to do what the 1979 show, or what New Glass Now did today, which is bringing contemporary glass to broader audiences. And the way that they did that was by renting out the first floor of Lever House [New York, New York], which Doug Heller talks about being able to—you know, the Brownies, the Girl Scouts would have an exhibition one week, you could rent it out for glass cause he’s self-deprecating. But these big, big displays that people could come into, and learn about this field. And those shows, I think, had an incredible impact. Their—the 1978 show had, for instance, Tom Patti on the cover, and I think that that piece went straight into a New York museum collection. And I think it’s not by coincidence that the New Glass Worldwide Survey cover—catalog cover—a year later, also had Tom Patti, which was a very fraught, fraught decision. Not fraught for the museum, I don’t think, but fraught for everybody else, including Paul Smith who [laughs] chose that piece by himself. So, I think that the—starting in that time the Heller Gallery really had a vision for what the field could be and how it could get there, and how it could get there was by framing the material for people, and I think that’s something that is still alive in the way the gallery approaches glass today.

Permalink

Susie Silbert talks about Habatat and Heller Galleries.

1:52 TranscriptSusie Silbert talks about Habatat and Heller Galleries. Oral history interview with Susie Silbert by Catherine Whalen, February 25, 2020, Bard Graduate Center. Clip length: 01:51.

Susie Silbert: It’s pretty interesting to have a market of contemporary glass that is in many ways dominated by two major galleries that have been there since the beginning, Heller and Habatat. And Habatat is interesting for a lot of different reasons, but even if you think about these two different—two different galleries, and the constraints put upon them. One, Heller Gallery in New York City with incredibly high rents and constrained space that that entails, and existing in a highly refined and variegated field of cultural production. Versus Habatat Gallery, which was founded in Michigan in—outside of Detroit, and maintains a very large footprint, and Habatat and over the years had spaces in Chicago, spaces in Massachusetts, and in Florida. It’s really sort of different, the kinds of approaches that enables, and the kinds of work that it can have. And I think Ferd—one of the things that Ferd and Habatat Gallery have done over the years is make glass very accessible to people, both in the way that they present the—they present glass, and the way that they talk about glass, and also in their forming, forming of glass as a social, as a really—as a social practice. So they have—they sponsor all kinds of different events. The Habatat Invitational, International Invitational, every year, now in its many—forty something year, and—or fiftieth, and they do a lot of international travel to introduce collectors to different regional markets. And I think that that packages glass in a way that makes it very approachable for very many people.

PermalinkBibliography

“Contemporary Art Glass Gallery and Heller Gallery.” American Craft 41, no. 2 (April/May 1981): 20–23.