CHAPTER IV: 1893 CHICAGO WORLD'S FAIR

At the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

“I am Expecting little trouble from the Missionary here every day for his trying to find out what I have been Doing in the Fair. For he came to me and said that I show some Dance against the Law and that I will Get my self into trouble.”

—George Hunt to Franz Boas, 15 January 1894

Most representatives of the Kwakwaka'wakw delegation at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. They stand before the painted façade of a Hope Island house in which Boas first stayed in 1886 and from which the settee in this exhibition came.

Left to right: Exu'las̱ [?], K'idiłame', John Drabble, Rachel Drabble, Iwanuxwdzi, Yekuk'walaga, Dukwayis, John Wanukw, Chicago Jim [?], George Hunt (in cap), G̱wayułalas, Xwani, Lucy Hunt, Tom Hemasi’lakw, David Hunt, Hixhaisagami. [Not pictured: Will Hunt, Malidi, T'łi'linuxw, Kostesalas (young son of Wanukw)]. Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, PM #93-1-10/100266.1.30.

Organized as a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, the World’s Columbian Exposition was a demonstration of progress, technology, and culture. In addition to exhibiting foreign societies and commodities for the American fairgoers, the exposition displayed and characterized America for both itself and the world at the close of the nineteenth century. The fair also introduced the newly defined field of anthropology to the American public.1

Frederic Ward Putnam, Harvard professor and curator of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnography, was appointed director of anthropology for the exposition. He hoped to present the Native peoples of the Americas “living as in olden times,” in contrast to the Indian Bureau’s exhibition of Native American children enrolled in boarding schools.2 Additional venues of Indigenous display included the Smithsonian’s exhibition (which combined efforts of the Bureau of American Ethnology and the U.S. National Museum), and the Midway Plaisance (whose commercial nature conflicted with Putnam’s desire for purely educational exhibitions).3 These diverse venues illustrated the breadth of motivations behind ethnographic displays, including scientific-based education, spectacle and entertainment, and nationalistic ideals.

In 1891, Putnam hired Franz Boas to lead the fair’s physical anthropology department and to supervise the Northwest Coast displays. While Boas dispatched collectors from Alaska to Washington State, he chose to center the exhibit around the Fort Rupert Kwagu’l with the assistance of George Hunt. In addition to collecting ceremonial and everyday objects, canoes, and even a house, Hunt coordinated a Kwakwaka'wakw delegation for the fair’s “ethnographic village.” Hunt recruited 20 individuals, including his wife, oldest son, and additional relatives, to live on the fairgrounds for seven months, where they danced, performed songs, and demonstrated craft-making.

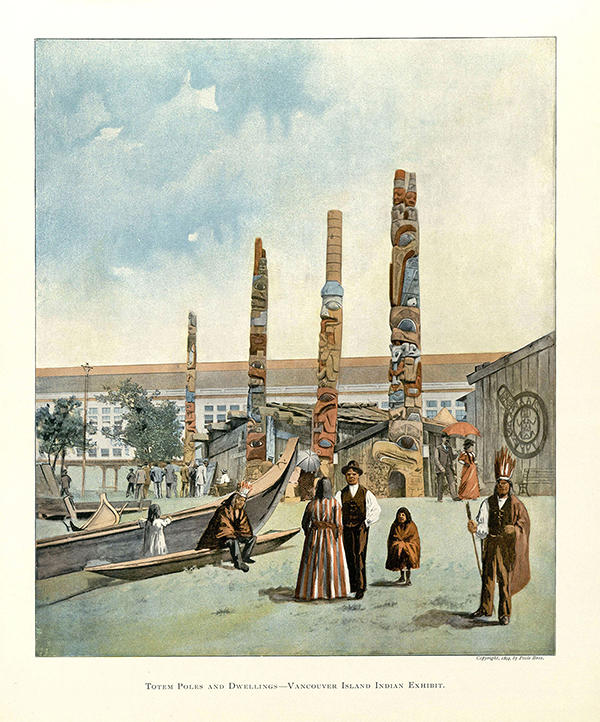

The ethnographic village was meant to provide fairgoers with a sense of Indigenous peoples from across the Americas and the world in their “normal conditions in their natural habitations,” as described in the fair’s official history.4 However the habitations, environment, and modes in which the Indigenous groups were paid to perform their culture were often a constructed display that differed greatly from the groups’ “normal” lives.5 When they arrived at the fair, the Kwakwaka'wakw troupe reassembled the house brought from Hope Island, which they spiritually prepared with a blessing ceremony before moving into both this house and the neighboring Haida one.6 It is unclear whether this house-opening was initiated by the delegation to culturally validate their activities in this unusual situation, was a cultural performance for the benefit of anthropologists and fairgoers, or was a combination of the two, as many such activities likely were. Visually, these re-constructed cedar plank houses would have contrasted strikingly with the new white-washed buildings that comprised the majority of the fair’s architectural landscape, paralleling how the displays of Indigenous peoples often diverged from the ideas of modern progress that were at the fair’s center (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Painted image of the “ethnographic village,” from Moses P. Handy, Vistas of the Fair in Color: A Portfolio of the Familiar Views of the World's Columbian Exposition, Part 16. Chicago: Poole Bros., ca. 1894 (unnumbered color plate).

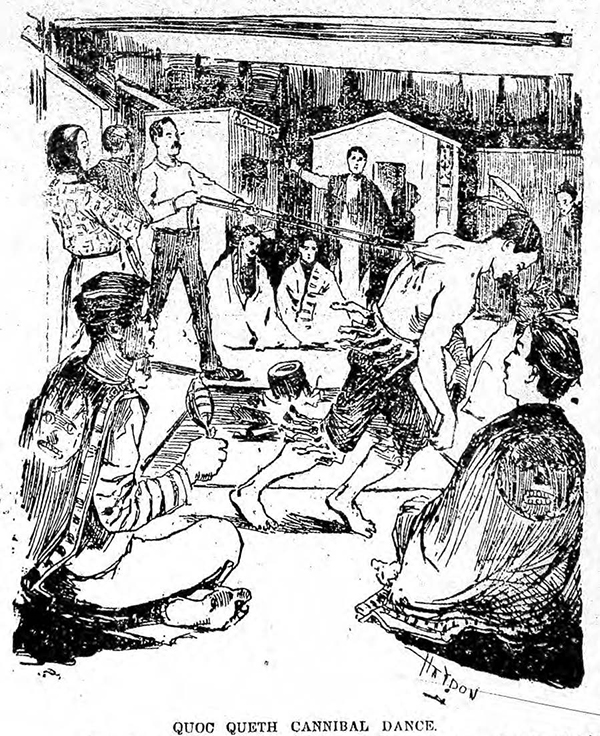

At the exposition, ideas of progress were closely tied to nationalistic aims. Similar to the U.S. Indian Bureau, the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs displayed residential school children with whom the young Canadian nation hoped to show the effects of their “liberal and paternal policy,” in contrast to the “wild” Kwakwaka'wakw in Boas’s exhibition.7 While the framing of the fair’s disparate displays provided some variable context for audience reactions, visitors’ pre-conceived notions seemed to guide their perceptions, as seen in first-hand accounts and newspaper reports of those who witnessed the Kwakwaka'wakw performances. Reports often focused on the “cannibal rites” (the dramatically staged Hamaťsa) and a dance that was labeled by onlookers as a “sun dance” (the Hawinalal or Warrior Dance), the latter of which featured a body piercing episode that was described in graphic and sensational language by many newspapers (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Drawing of the Hawinalal (Warrior Dance), mistakenly labeled “Cannibal Dance.” The Chicago Times, June 6, 1893, page 1.

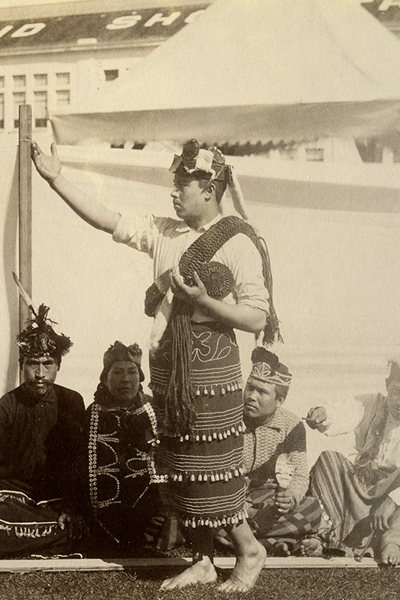

While fairgoers’ views on Indigenous peoples might have remained fairly static, the fair itself was a dynamic site of ethnographic knowledge production. Boas observed many Winter Ceremonial dances for the first time, and organized photography of the delegation in their regalia. He also recorded ethnographic notes with George Hunt, whom he taught to transcribe the Kwak̓wala language with a phonetically detailed script. Lastly, Boas hired musicologist John Fillmore to record Kwak̓wala songs on wax cylinders.

The exposition also provided an opportunity for the delegation to enact cultural continuity. The potlatch ban had been passed eight years prior in Canada, and the American fair context allowed the Kwakwaka'wakw to conduct some of their outlawed winter dances, albeit in a non-ceremonial context and season. Even in this foreign location, the hereditary nature of the dance societies seemed to be honored—with delegates performing dances to which they had personal rights—demonstrating agency to adapt the ceremonies as appropriate. The troupe also consumed eulachon oil, exchanged gifts with other Indigenous people, and performed the house-opening ceremony.8 All of these activities exemplify ways in which the Kwakwaka'wakw worked to subvert colonial authority and ensure cultural survival through both resistance and compromise.9

By Emily Hayflick

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Dexter, “Putnam’s Problems Popularizing Anthropology,” 315.

- Hinsley, “Anthropology as Education and Entertainment,” 25, 29-31.

- Even Putnam’s exhibitions were not able to avoid commercialism, as the Indigenous delegations and their sponsors wanted to sell crafts to earn extra money. Hinsley, “Anthropology as Education and Entertainment,” 29.

- Johnson, A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 315; Jacknis, “Northwest Coast Indian Culture and the World's Columbian Exposition,” 97. In the end, Putnam only managed to coordinate six or seven delegations from Canada, the U.S., and British Guiana, which was not the breadth of examples that he had originally hoped for.

- These abnormalities included concessionaries forcing Inuit individuals to wear fur clothing in 70-degree weather and the exclusion of European-American produced items, such as Hudson Bay Company blankets. Hinsley, “Anthropology as Education and Entertainment,” 42; Raibmon, "Theatres of Contact,” 159.

- For a map of the fairgrounds see: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104c.ct002834/?r=-0.502,0,2.004,0.976,0. The “ethnographic village” is at the bottom right, just east of the South Pond. The “Indian school” is located just north of the village.

- Saunders, Report on the World's Columbian Exposition, 19.

- The Haudenosaunee headpiece worn by Chicago Jim in photographs from the fair was likely received in a gift exchange with a member of the Haudenosaunee delegation.

- Raibmon, "Theatres of Contact," 186; Glass, “Conspicuous Consumption” and “‘The Thin Edge of the Wedge:’ Dancing Around the Potlatch Ban.”