CHAPTER IX: COMMUNITY REPRODUCTIONS

Rattle

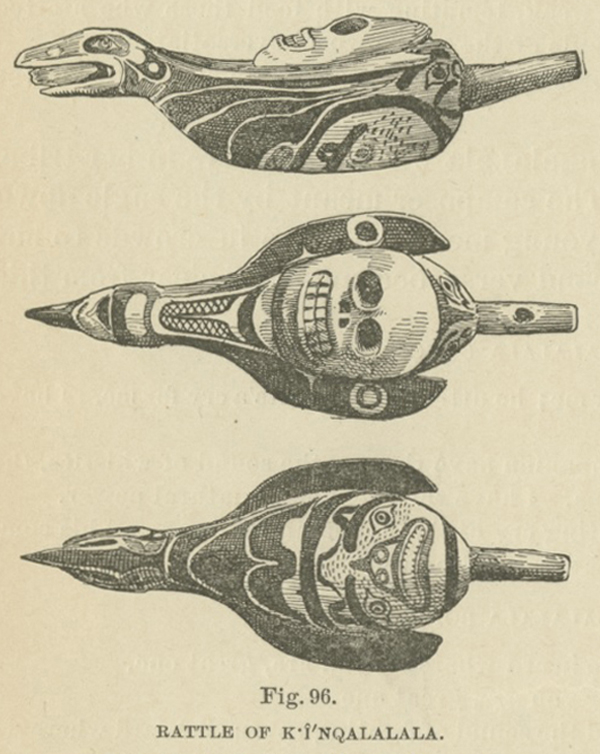

Figure 96 from Boas’s 1897 book.

Hunt’s 1920s notes on figure 96:

Hāᵋyā´tālāł yādᴇn

Rattle Dancer Rattle. these Rattles there

should Be twenty four of them in a set

I cant find out the story the. Rattle

Dancer Rattles. which is Rattled By

twenty attandent of the Rattle Dancer

or Hayatalał. these Rattle Belong to the

ts!ē´gᴇłᵋedox tribe. and came in marriage

to the g̣osgeᵋmox. and from them it

was given to the senʟ!ᴇm Brother

tribe of the kwā´goł in marriage

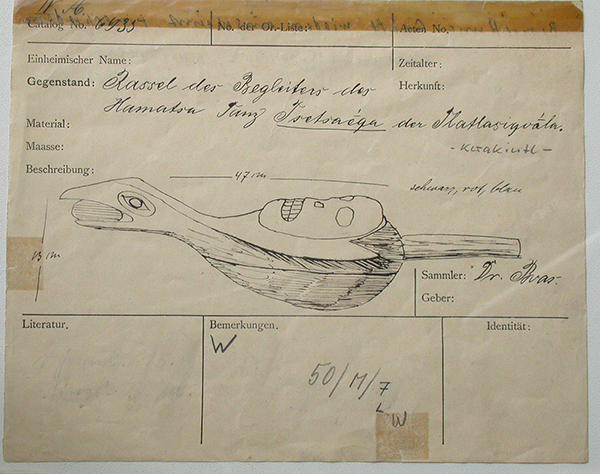

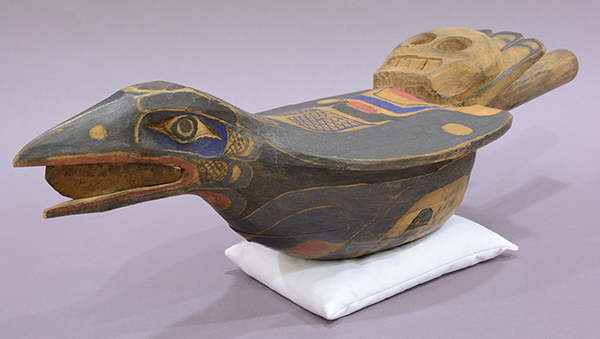

This rattle, a contemporary version of one collected by Franz Boas (Fig. 1), represents one of the interpretive complexities of Kwakwaka’wakw art. Boas and Hunt’s collection, publication, and revision records do not always agree as to its significance, and such rattles are no longer in ceremonial use. Stylistically, it seems to be a unique variation on the canonical and regionally widespread raven rattles, which often feature a reclining humanoid figure sharing a tongue with another creature (Fig. 2).1 Instead, this distinctive rattle has a human skull carved on its back and an iconographically ambiguous face painted on its belly. An oval piece of copper (now missing) was once clearly visible in the raven’s mouth, as indicated by the rattle’s illustration in Boas’s 1897 book as well as a drawing on its extant catalog card (Fig. 3).2 Boas also illustrated a very similar rattle collected in 1881 by Johan Adrian Jacobsen, which still retains its copper mouthpiece (Fig. 4). Since some raven rattles from the northern coast are thought to depict the widespread story of Raven stealing the sun, perhaps the copper disk was derived from this narrative element.

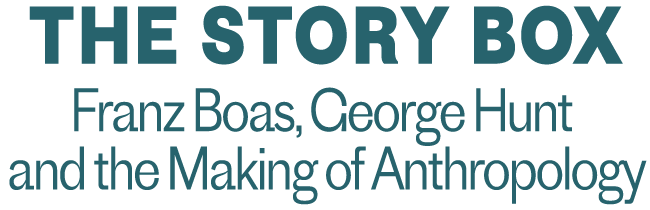

Fig. 1. Rattle, Kwakwaka’wakw, collected by Franz Boas in 1886. Painted wood. Courtesy of U’mista Cultural Centre and bpk Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Art Resource, NY.

Fig. 2. A “classic” Tsimshian Raven Rattle. Collected by Israel Powell, 1880–85. Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, 16/292.

Fig. 3. The original rattle’s historic catalog card in the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, IVA 6935. Research photograph by Aaron Glass.

Fig. 4 Rattle, Kwakwaka’wakw, collected by Johan Adrian Jacobsen in 1881. Painted wood and copper. Note the piece of copper in the raven’s mouth, which the rattle in figure 1 featured at the time of collection. Courtesy of U’mista Cultural Centre and bpk Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin /Lars Malareck / Art Resource, NY.

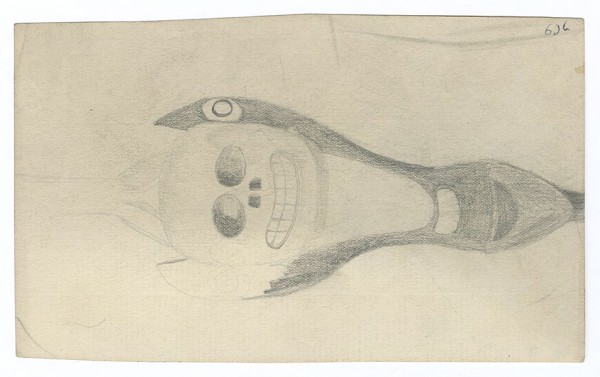

Boas likely purchased his rattle in Alert Bay in 1886, during his first coastal fieldwork, and then sold it to Berlin’s Royal Ethnographical Museum.3 Regarding the distinctive imagery of both his and Jacobsen’s rattles, Boas wrote that “the skull indicates that the hamats’a is filled with the desire of eating skulls,” and he asserted that they were used by the Kankalatłala, a female attendant of the Hamat̕sa (Cannibal Dancer) who helps to tame him out of his wild state. Based on consultations at the World’s Columbian Exposition, when Boas likely showed troupe members his own drawing of the rattle (Fig. 5), he also connected it with a particular Kankalatłala song belonging to the ’Namgis of Alert Bay.4 Although historic and contemporary Hamat̕sa attendants typically shake round rattles decorated with painted or carved skulls, Kwakwaka’wakw consultants today report no known use of raven rattles in this context.

Fig. 5. Undated drawing by Franz Boas of the rattle he collected in 1886. Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, Z/ 44 U.

In fact, George Hunt’s revisions to the 1897 text contradict Boas’s attribution, declaring that these rattles (yadan in Kwak̓wala) were used—in sets of 12 or 24—in a completely separate prerogative known as “The Rattle Dance” (Hayatalał). In his notes written in the 1920s (featured above), Hunt detailed how this dance was transferred in marriage from the Gusgimaxw people of Quatsino Sound to the Kwagu’ł of Fort Rupert; a decade later, Hunt suggested that the dance originated among the Nuu-chah-nulth neighbors of the Gusgimaxw, and he revealed the marriage in question to have been that of Xwani and Malidi—two of the troupe members who went to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.5 What is so striking in both generations of Hunt’s notes is the consistency and expanding detail of his information, although it is not easy to harmonize with Boas and Jacobsen’s (internally confusing) collection data or Boas’s published account. Because skull imagery is common on masks and other regalia used in the Hamat̕sa, Boas may have assumed rather than documented this connection. Or perhaps we have another case where similar material forms spread between villages but were adapted to different, local prerogatives.6

Because the use and knowledge of these distinctive rattles ceased in the twentieth century, people today debate its identity and the archival records in order to enable a revival. The Boas 1897 Critical Edition project team is working with Indigenous community members to disentangle the material and textual record. In the meantime, Kwakwaka’wakw carver Wayne Alfred created the version featured here based on photographs of the original. He also worked with young apprentices in Alert Bay to produce additional rattles for the “set” as identified by Hunt. These will enter U’mista Cultural Centre’s Loan Collection for the use of families that can demonstrate historic ties to the Rattle Dance as its history comes into clearer view.

By Avery Schroeder and Aaron Glass

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Gould, Iconography of the Northwest Coast Raven Rattle, ii; Glass, Objects of Exchange, 108-112.

- Staff at the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin (personal correspondence) were not able to determine when the piece of copper was dislodged or removed, or whether it still exists. Also noteworthy is the piece of cedar bark currently wrapped around the rattle’s neck (as visible in Fig. 1), which does not appear to be original to the piece (evidenced by its absence in historic drawings). The cedar-bark ring is not mentioned in a conservation report of this object conducted in 1970, and first appears in a photograph published in a 1990 exhibition catalog (Kasten, Maskentanze der Kwakiutl, 140). Our thanks to Peter Bolz, Erich Kasten, and Monika Zessnik in Berlin for helping sort through these material quandaries.

- Boas, The Social Organization, 461, 695. Scholars debate the collection site of these two distinctive rattles. The Berlin museum’s catalog card for Boas’s rattle suggests Hope Island as its purchase location, but Boas clearly includes it on his original collection list with other items acquired in Alert Bay (Hatoum, The Berlin Boas Northwest Coast Collection, 64). Jacobsen’s collection data in the Berlin museum suggest he acquired his similar rattle in Fort Rupert, but original diaries and shipping records (in a Hamburg archive) also indicate Alert Bay as its purchase location, lending credence to Boas’s association of the rattles with that village (Hatoum, personal correspondence; see also Glass and Hatoum, “From British Columbia to Berlin and Back Again.”). To compound the mystery, current Kwakwaka’wakw consultants report that the rattles show stylistic hallmarks of the northern Heiltsuk people, from whom they received numerous prerogatives in the nineteenth century.

- Boas, The Social Organization, 461-62. In Boas’s original 1886 collection notes, he called the object a “Tsesemkila” rattle (a term not recognized by consultants today), and implied that it was used by male attendants to the Hamat̕sa. In his 1893 notebook from Chicago, Boas jotted “Berlin rattle. Raven(,) copper in Mouth. Dead head [skull] on back” next to lyrics of the Kankalatłala song he later published in the 1897 book (Rainer Hatoum, personal correspondence).

- Hunt, “Kwakiutl Materials,” 5559-5564. When asked about the potential connection to the Nuu-chah-nulth (“Nootka”), historian Haa’yuups (Ron Hamilton, personal communication) said that some versions of the Tluukwaana (Winter Wolf Ceremonial) feature a series of crawling wolf dancers (perhaps up to twenty four, and always in an even number), each accompanied by an attendant shaking a bird-shaped rattle. He added that both copper and skull imagery are consistent with Tluukwaana regalia. While he did not recognize these distinctive rattles per se, this does suggest a potential Nuu-chah-nulth prototype for the Kwakwaka’wakw adaptations, as Hunt recorded.

- Some corroborating evidence for this latter scenario is provided by Boas himself, who writes in passing that among the T’lat’lasikwala of Hope Island, the term “yiai´atalaʟ” (which Boas translated, like the related term Hayatalał, as “Rattle Dance”) was used to describe the K’uminoga Dance, in which a woman is possessed by the man-eating spirit, adorns herself with skulls, and carries a rattle (Boas, The Social Organization, 463; Judith Berman, personal communication). In this scenario, there may have been up to three paths of diffusion (perhaps originating with the Nuu-chah-nulth) for the skull-adorned rattle and/or the “Rattle Dance” among the Kwakwaka’wakw: one path from Quatsino Sound to Fort Rupert, where the dance name and unique rattles were used as a stand-alone prerogative; one to Alert Bay, where the rattle (but not the dance name) was used by at least one particular female attendant to the Hamat̕sa; and one to Hope Island, where the dance name (and possibly the distinctive rattle) was applied to the K’uminoga.