CHAPTER II: CULTURAL BACKGROUND

Kwakwaka’wakw Social and Ceremonial Organization

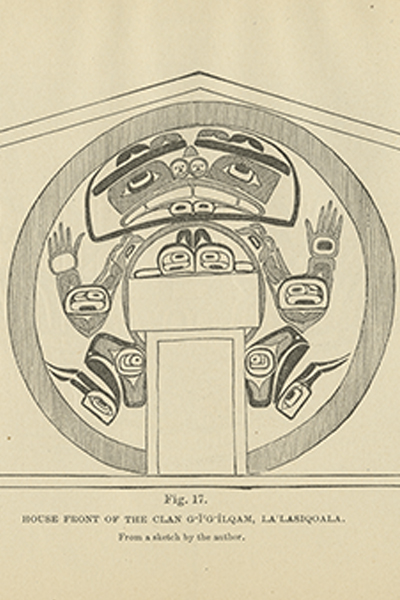

Figure 17 from Boas’s 1897 book, depicting a house in X̱wa̱mdasbe’.

Kwakwaka’wakw means “The people who speak Kwak̓wala.” The term refers to more than 18 First Nations residing on the central coast of British Columbia. The word Kwakiutl, popularized by Franz Boas and others, is an Anglicized form of Kwagu’l, the band at Fort Rupert. Each band is divided into extended kin units called ’na’mima (loosely, “clans”) that share a common name, ancestor, charter stories, territories, and tangible and intangible properties. Both ’na’mima and families are identified by heraldic crests, typically in the form of animals or supernatural beings, which adorn house fronts, totem poles, furnishings, storage boxes, and clothing.

Through masked dance and song, people accrue social prestige and maintain reciprocal relations with the various beings that animate the world. Ceremonial life is structured around two ritual cycles. The more secular Tla’sala or Dła̱wa̱lax̱a (Peace or Chief’s Dances) are governed by ’na’mima membership and are used to display the dlugwe’ (hereditary treasures) that are part of a family’s gildas (box of treasures). These are contrasted with the sacred T̕seka or T̕sit̕seka (Red Cedar Bark Dances or Winter Ceremonials), which are used to initiate members into ranked dance guilds that Boas called “secret societies.” Each T̕seka society is distinguished by the use of specific masks, cedar-bark regalia, and songs, and is linked to a particular initiating spirit. Rights to these are inherited or passed along in marriage.

At potlatches, host families mark important events by displaying hereditary wealth and validating claims through oratory, dance, and gifts to witnesses. During the 19th century, political, legal, spiritual, and economic order was maintained through the potlatch. In 1884, pressure from colonial agents in British Columbia led the Canadian government to ban the potlatch and its dances in an effort to assimilate and convert First Nations. The Kwakwaka’wakw resisted the ban, but increasing pressure, arrests, and regalia confiscations sent the potlatch underground. All of Boas’s research occurred during the potlatch prohibition, which underpinned his 1897 concern that the “laws and stories” might be forgotten. Although he advocated on their behalf to Canadian authorities, Boas rarely mentioned the law in his ethnographic texts. Since the ban was dropped in 1951, Kwakwaka’wakw families have returned to public potlatching as an expression of their enduring sovereignty.