CHAPTER I: FRANZ BOAS AND GEORGE HUNT

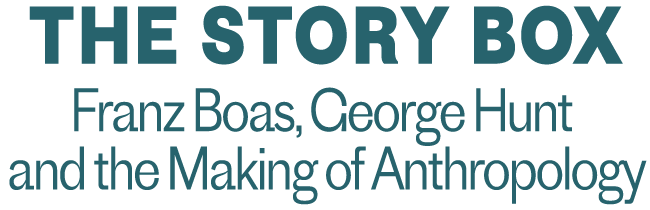

George Hunt

One of the most influential figures in Northwest Coast ethnography, George Hunt (Kixitasu’) (1854-1933) is critical to the material and ethnological legacy of Indigenous peoples from this region. Born in 1854 to Robert Hunt, a British fur trader, and Mary Ebbets (Anisalaga), a Tongass Tlingit noblewoman from Southeast Alaska, George Hunt spent most of his life in Fort Rupert, British Columbia. There, he learned to speak Kwak̓wala and was incorporated into the community through his marriages to two Kwakwaka’wakw women, which granted him local hereditary rights and privileges that supplemented the Tlingit customs and prerogatives he passed to his descendants.1

After a stint in 1879 as an interpreter for Israel Powell, British Columbia’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Hunt worked as a field guide and collector for a number of people, including Johan Adrian Jacobsen in 1881-82.2 In this capacity, Hunt supplemented Jacobsen’s minimal knowledge about the language and geography of the region, provided introductions to many local communities, and brokered some sales.3 In 1888, Hunt met Franz Boas, who would become his most significant employer and research partner. Hunt’s first major museum collecting effort for Boas was a commission to assemble displays for the Anthropology Department at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Later serving as a field worker on the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897-1902), Hunt was crucial in helping Boas to establish a large and well-documented Kwakwaka’wakw collection at the American Museum of Natural History.4 Hunt also assisted other collectors and ethnographers (such as Edward S. Curtis and George Gustav Heye), and made significant contributions to numerous institutions, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the Milwaukee Public Museum, and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin.5

From the time he began assisting Boas in 1889 until his death in 1933, Hunt compiled and edited thousands of pages of notes, translations, and annotations for and in response to Boas’s publications, thereby contributing to the first major wave of professional ethnographic writing to focus on Indigenous cultures of the Northwest Coast.6 As an ethnographer, Hunt utilized photography, oral history, object collection, and participant observation to document and analyze Kwakwaka’wakw culture, especially as he was becoming more intimately familiar with it as an adult participant in the potlatch and ceremonial system. Based on the access he enjoyed as a local resident and an affinal member of multiple ’na’mima over his life, Hunt’s own research was essential to the success of much of Boas’s work.7 While Boas credits Hunt’s “notes” on the title page and in the preface of his pivotal 1897 monograph, The Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians, Hunt is not sufficiently acknowledged as its co-author.

Hunt participated in other kinds of ethnographic work as well, traveling to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago with Boas to coordinate and perform with a visiting group of Kwakwaka’wakw. From 1911 to 1914, he assisted Edward S. Curtis with his photography of Kwakwaka’wakw life and with the feature film, In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914).8 Boas preferred that Hunt not work for rival collectors and ethnographers, and Hunt often reassured Boas of his loyalty; for instance, Hunt was critical of Curtis’s work in letters to Boas, decrying the photographer’s inaccuracies and lack of interest in recording detailed cultural context.9 Hunt went on to facilitate other film projects among the Kwakwaka’wakw, from short newsreels to Boas’s own 1930 experiments in filmic documentation.10

Hunt passed away in 1933 in Fort Rupert after more than fifty years of ethnographic work. Few of his most valuable contributions to Northwest Coast anthropological texts and museum collections appeared under his name. Only three publications, “The Rival Chiefs: a Kwakiutl Story,” “Kwakiutl Texts,” and “Kwakiutl Texts–Second Series,” explicitly credited him as an author or co-author. However, scholars and Hunt’s many descendants have been active in rectifying his absence from the historical record.11 They continue his legacy of advancing ethnographic, material, and linguistic research, and advocating for the preservation and sovereignty of Kwakwaka’wakw communities. Exhibition artist Corrine Hunt speaks of the contemporary resonance of her great-grandfather’s work with Boas, especially when kept in relation to oral history and ceremonial transmission: “The book itself is adjunct to the heritage that has continued through the potlatch ban. Maybe the documentation has helped along the way, but paired together they’re a powerful unit… We have revived many names and songs, as a kind of reinforcement of the things we know and the knowledge that has been shared by different people in various villages.”

By Tessa Goldsher and Aaron Glass

Objects Collected by Hunt

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Glass, Berman, and Hatoum, “Reassembling The Social Organization;” Cannizzo, “George Hunt and the Invention of Kwakiutl Culture.”

- Jacknis, “George Hunt, Kwakiutl Photographer,” 181.

- Bolz and Sanner, Native American Art, 168-82; Glass & Hatoum, “From British Columbia to Berlin and Back Again,” 5.

- Jonaitis, From the Land of the Totem Poles, 163, 171-173; Jacknis, “George Hunt, Collector of Indian Specimens,” 190.

- Jacknis, “George Hunt, Collector of Indian Specimens,” 201; Gidley, “Three Cultural Brokers.”

- Berman, “Hunt, George (Maxwalagalis, Q’ixitasu’),” 522.

- Berman, “‘The Culture as it Appears to the Indian Himself’,” “Unpublished Materials of Franz Boas and George Hunt,” and “Hunt, George (Xawe,’ ’Maxwalagalis, K’ixitasu, Nołq’ołala).”

- Glass, “A Cannibal in the Archive;” Evans and Glass, Return to the Land of the Head Hunters, 16 and passim.

- Jacknis “George Hunt, Kwakiutl Photographer,” 144-45.

- Morris, New Worlds from Fragments; Bunn-Marcuse, “Kwakwaka’wakw on Film.”

- See Webster, “Contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatches” and “Consumers, Then and Now”; Nicolson, “Starting from the Beginning.”