CHAPTER I: FRANZ BOAS AND GEORGE HUNT

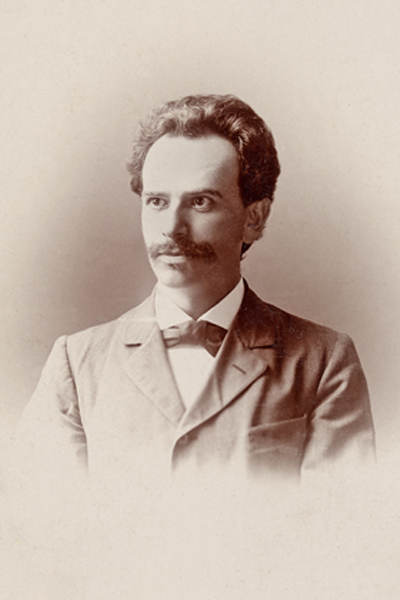

Franz Boas

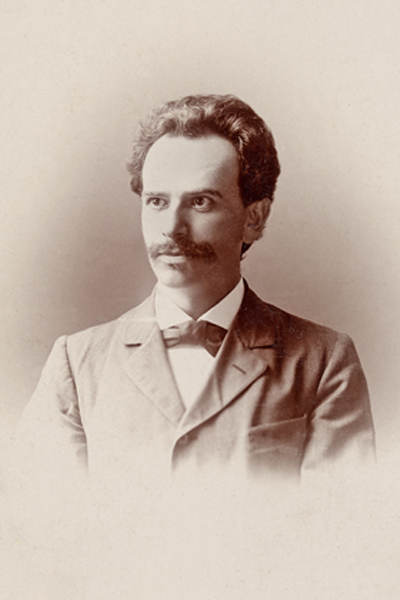

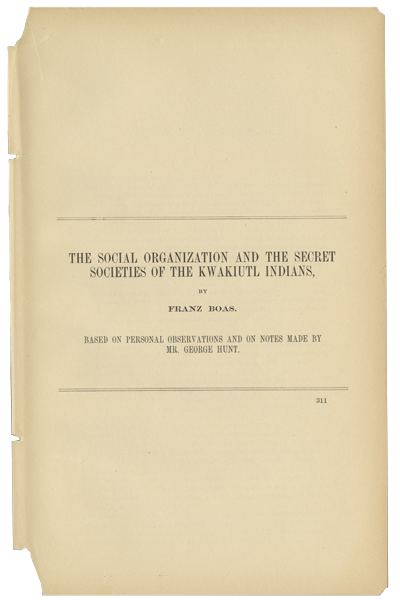

Franz Boas (1858-1942) was among the most important founders of professional anthropology in North America and a vocal opponent of scientific racism. His detailed ethnographic research among the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of British Columbia—first summarized in his 1897 monograph—provided evidence for his influential critique of social evolutionary thought and his concept of culture as learned, locally situated, and divorced from human biology.

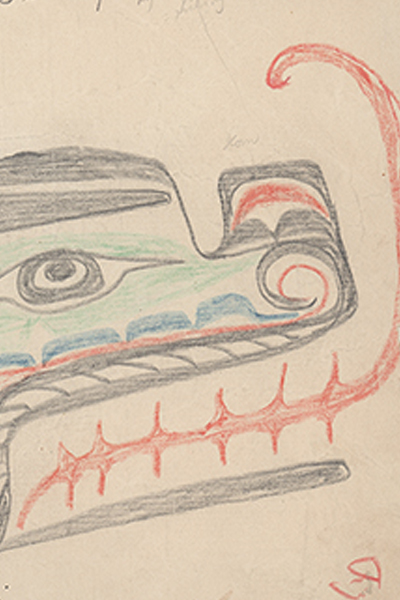

Born in Minden, Germany, in 1858, Boas entered German intellectual life at a moment in which scholars were looking for ways to quantify the human experience and questioning received ideas about cultural progress and racial difference.1 Boas first studied physics at Heidelberg and Bonn, then psychophysics at Kiel, and eventually geography at Minden.2 This final choice led him to the science of human interaction and development and the theories of geographers such as Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter, whose student Theobald Fischer was Boas’s thesis advisor at Kiel. Ritter considered ethnography to be a part of geographic inquiry, especially as a means to redefine racial groups in terms of their language, culture, and physical attributes.3 Those ideas spurred Boas to conduct fieldwork between 1883 and1884 among the Inuit on Baffin Island in the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Afterward, in Berlin, he applied his insights to a job helping to catalog the Jacobsen collection at the Royal Ethnography Museum, which included hundreds of items from the Kwakwaka’wakw. Although fascinated by the ceremonial masks and regalia, Boas found that their cultural context had not been adequately documented, which made their interpretation difficult. Hoping to reconnect the objects with their original narratives and ritual practices, Boas left Berlin for British Columbia in 1886 armed with photographs and drawings of the Jacobsen collection.4 As a Jew, Boas was concerned about his limited professional prospects in Germany and he soon decided to emigrate to North America, where he settled down in New York City.

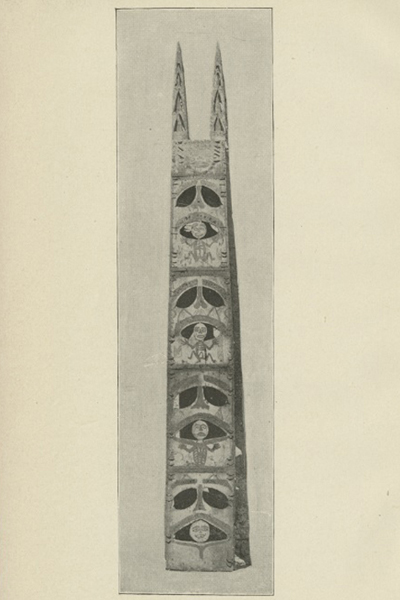

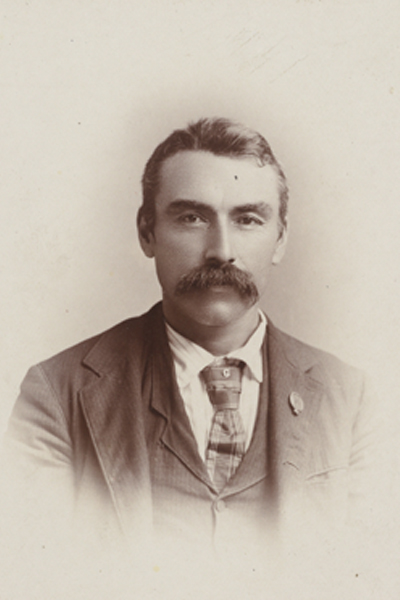

While working in British Columbia over the next decade, Boas concentrated on the Kwakwaka’wakw, recording information about their communities, social organization, and ceremonial life. He also collected objects to sell to museums in order to help fund his independent research. Boas offered his first, small, 1886 collection and its accompanying cultural documentation to the American Museum of Natural History, where he hoped to secure a curatorial position. When they refused both his objects and his job prospects, he sold the bulk of the collection to the Berlin museum.5 In 1893, he helped organize the Anthropology Department at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which also failed to result in a permanent post. Boas returned to British Columbia in 1894 to join George Hunt’s family during the Winter Ceremonials at Fort Rupert. Between 1895 and 1896, Boas and Hunt clarified the notes from Chicago and Fort Rupert, with Hunt fleshing out the context for Boas’s observations, and together they produced the 1897 monograph.

In 1896, Boas was finally appointed as an Assistant Curator at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), where he revolutionized ethnographic exhibition practice by organizing the display of Northwest Coast objects by tribal context rather than their place in assumed evolutionary stages of development.6 By considering the conditions of an object’s use and symbolic meaning, rather than merely focusing on its formal or physical characteristics, Boas presented each tribal group as a coherent cultural whole—an idea that had its genesis in his education in Germany. During his decade at AMNH, Boas also directed the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, whose team of fieldworkers collected and documented thousands of objects, conducted detailed ethnographic research, and published extensive reports on the Indigenous peoples of the North Pacific Coast, Alaska, and Siberia.7

Upon leaving AMNH in 1905, Boas moved to a full-time faculty position at Columbia University, where he had been lecturing for a few years. There, he influenced the next generation of American anthropologists, including Alfred Kroeber, Ruth Benedict, Edward Sapir, and Margaret Mead, in whom he inculcated the ideals of careful fieldwork, cultural relativism, and holistic documentation that exemplify his transformation to anthropology. In addition to his voluminous ethnographic publications, Boas also wrote books, such as The Mind of Primitive Man (1911), Primitive Art (1927), Anthropology and Modern Life (1928), and Race, Language, and Culture (1940), which carried his vision for anthropology to a wider public. Ultimately, Boas’s work revolutionized many fields, including comparative ethnology, folklore, linguistics, art history, and museology, and changed our notion about what it means to be human.8

By Tobah Aukland-Peck

Objects Collected by Boas

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Bunzl, “Franz Boas and the Humboldtian Tradition,” 17-78.

- For more on Boas’s academic training in Germany, see Chapter 3 of Cole, Franz Boas.

- Stocking, A Franz Boas Reader, 84.

- Glass, “Drawing on Museums,” 3.

- Cole, Franz Boas, 108; Hatoum, “The Berlin Boas Northwest Coast Collection.”

- Jacknis, “Franz Boas and Exhibits,” 77-80.

- Jonaitis, From the Land of the Totem Poles, 154-212; Krupnik and Fitzhugh, Gateways; Kendall and Krupnik, Constructing Cultures Then and Now; see also Chapter 11 of Cole, Franz Boas.

- Darnell, “Who was Franz Boas?”