CHAPTER III: EARLY FIELDWORK AND COLLECTIONS

Fool or Sunbeam? The Problem of Typology

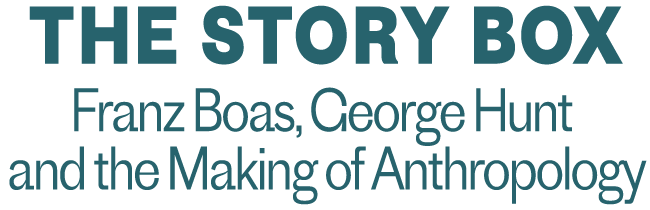

Lion-type Mask

Unknown maker, Kwakwaka’wakw

Wood, pigment, twine

10 3/4 x 7 3/4 x 5 1/2 in. (27.5 x 19.5 x 14 cm)

Owned by R. G. Whitfield and purchased by Augustus Franks in 1877

British Museum, Am +.436

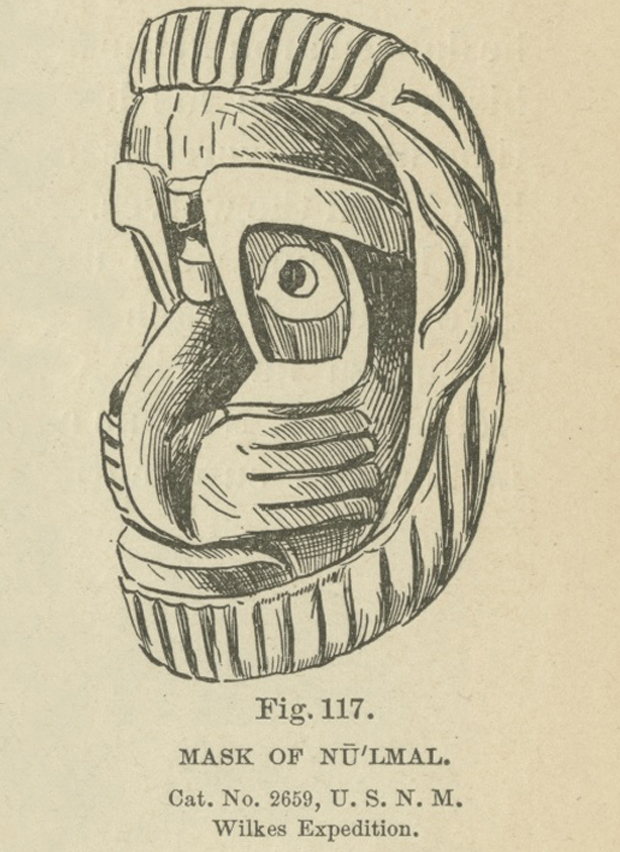

Lion-type Mask

Unknown maker, Kwakwaka’wakw

Wood, pigment, spruce root, traces of mica or shell

10 1/2 x 8 1/4 x 4 in. (27 x 21 x 10 cm)

Collected by James Scarborough of the United States Exploring Expedition in 1841 and accessioned in 1858

National Museum of Natural History, 2659

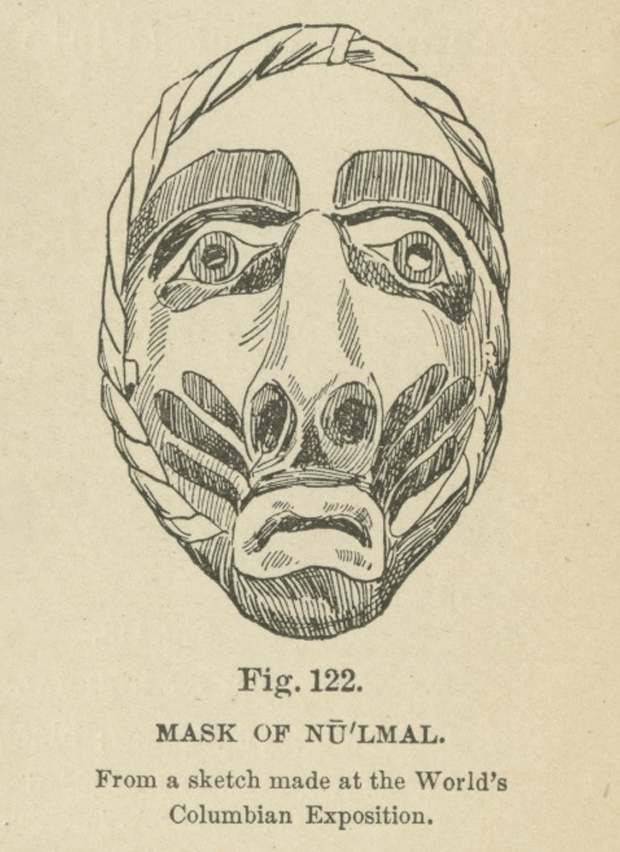

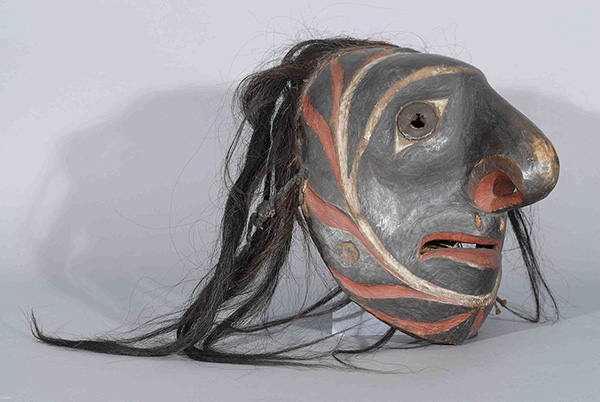

Mask

Unknown maker, Kwakwaka’wakw

Wood, paint, textile, iron alloy

11 3/4 x 8 x 6 3/4 in. (30 x 20.3 x 17.1 cm)

Collected by George Hunt around 1891 for display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and accessioned in 1897

Field Museum, 19219

Plate 34 from Boas’s 1897 book.

Hunt’s 1920s notes on plate 34:

sē´pāxāᵋēs ᴇmł

sun Beam shining Down mask. this

mask Belong to the gop!enox tribe

Possibly the oldest of the three masks, this one is most stylistically similar to the “cathead” carvings on European ships, with its mane, whiskers, furrowed brow, and downturned mouth. A twine cord runs through to the back and was held in the dancer’s teeth.

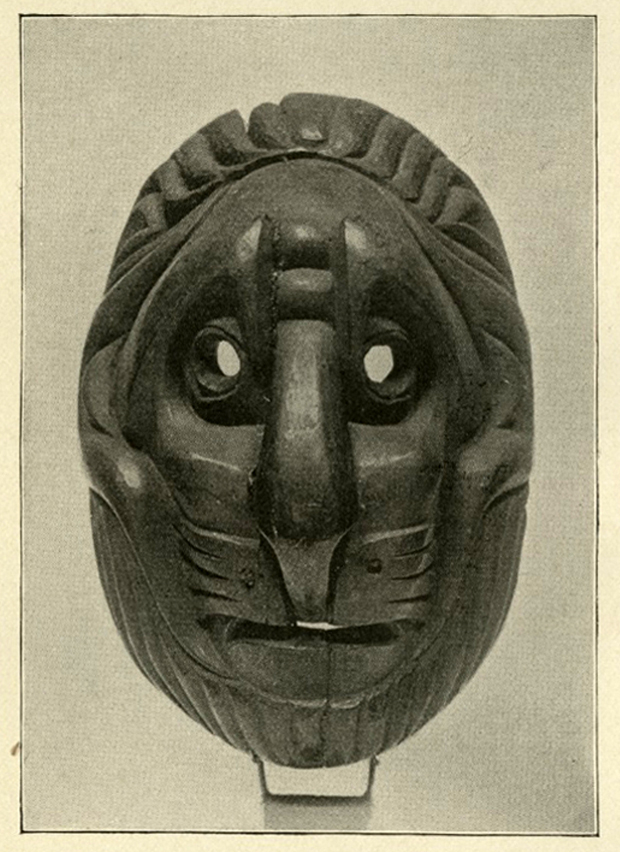

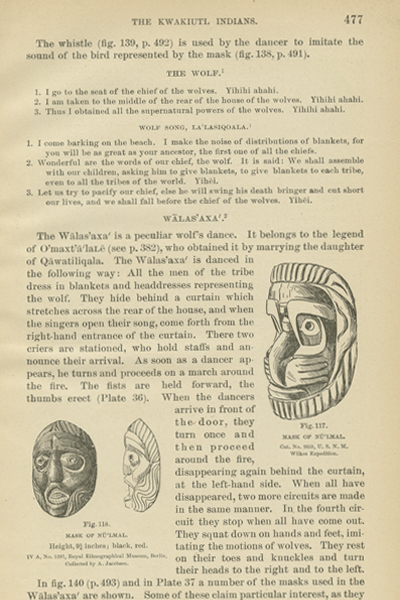

Figure 117 from Boas’s 1897 book.

Hunt’s 1920s notes on figure 117:

sē´pā´xāᵋēs ᴇmł

shineing Down sun Beam. this Belong

to the Pepᴇᵋweʟ!enox nᴇmemot of the

ʟ!āsq!enox tribe this Belong to the

Baxwes Dance

This example is a stylistic intermediary, with the leonine features (plus reflective mica or shell) mapped onto a more humanoid form. The upper rim features multiple holes that once held strands of inlaid hair, as on other extant masks of this type.

During the first decade of his research on the Northwest Coast, Boas was dedicated to sorting Indigenous material culture into discrete classifications generated by local, as opposed to European, cultural forms and terms. In his 1897 book, Boas categorized these three masks as Nulamal (“Fool Dancer”) because of their pronounced noses and the twisted rings encircling their faces.1 The Nulamal is an aggressive figure in the Winter Ceremonial who enforces proper cultural protocols by punishing those who behave poorly, and is commonly recognized by his high-pitched cries and unpleasant appearance (for instance, masked dancers sometimes have simulated mucous streaming from their nose).

Building on Boas, art historians commonly identify two styles of Nulamal mask: a human-type (Fig. 1) and a lion-type. The latter masks are thought to have been derived from lion figures seen on European ships or maritime material culture in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In particular, “catheads” constructed of wood, iron, or bronze were positioned on the outboard end of some ships’ anchor-bearing beams (Fig. 2).2 Given its prominence on Royal Navy flags, figureheads, and carved plaques, it is possible that First Nations understood the lion as a kind of “crest” of the English (whom they called “King George’s men”) as a way to distinguish them from Americans (“Boston men”).3 Typical lion-type masks exhibit a twisted, leonine mane with rounded projections (possibly representing ears) on either side; prominent ridges in between thick, up-raised eyebrows; rounded, elongated noses with the septum attached to the upper lip (rather than protruding from the face, as seen on humanoid masks); radiating whiskers; and a downturned scowl (sometimes with carved or inlaid teeth).

Fig. 1. Kwakwaka’wakw mask collected by Johan Adrian Jacobsen, ca. 1882. This is a typical humanoid Nulamal mask, with its pronounced nose and rim design invoking twisted cedar-bark rings. Wood, hair, paint. Courtesy of U’mista Cultural Centre and bpk Bildagentur / Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 2. USS Constitution port bow cathead carving. Late 20th century reconstruction. Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment, Boston.

In 1899, Hunt collected a lion-type mask, now at the American Museum of Natural History, along with a Gusgimaxw charter narrative about “Chief-Destroyer” that identifies such masks as representing Sepa’xais (“Shining Down Sun Beam”), a sky-dwelling spirit being.4 Boas initially dismissed this re-classification, suspecting Hunt’s suppliers of relating the masks to stories in order to increase their monetary value.5 However, in his subsequent revisions to the 1897 volume, Hunt associated four other Sepa’xais masks (including two of those pictured here) with specific Kwakwaka’wakw bands from around Quatsino Sound.6 Due to their location on the outer coast, Quatsino communities were some of the first Kwakwaka’wakw to have sustained interaction with—and collections made by—European explorers and merchants. By the time he published Primitive Art in the late 1920s, Boas acknowledged that Hunt’s alternative reading might be correct for at least some users of the lion-type masks.7

Based on the available material, textual, and oral history evidence, it seems that Kwakwaka’wakw carvers around Quatsino Sound first adapted European leonine imagery to masked representations of Sepa’xais in the early nineteenth century.8 This perhaps resulted from a visual association between sunbeams and the radiating hair of an exotic lion’s mane. Like some gilded catheads, these masks often feature reflective materials such as mica or copper, a trait they share with other Kwakwaka’wakw carvings depicting celestial beings. In subsequent decades, the innovative motif may have diffused to neighboring coastal groups that lacked Sepa’xais stories and prerogatives. In these villages, it appears that some of the leonine imagery was absorbed into the more widespread Nulamal tradition, as illustrated by the latest and most humanoid mask featured here (where the mane of hair now mimics twisted cedar-bark fringe, and the former whiskers have become painted lines that invoke streaming mucous).

In any case, the lion-type masks have not been carved or used ceremonially in Kwakwaka’wakw communities for the past century, making their definitive identification very difficult. With the loss of the Sepa’xais association and the absorption of leonine imagery into the more common Nulamal masks, many speculate as to why this figure was depicted in this distinctive style. Contemporary artist and hereditary chief Beau Dick once pointedly noted that the choice to use Euro-American imagery to represent the boorish and authoritarian Nulamal was “not without significance.”9

By Lillia McEnaney and Aaron Glass

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Boas, The Social Organization, 468-479.

- Bill Holm, in a 1975 conference paper (“Some More Conundrums…”), first suggested the influence of cathead carvings; see also Holm, The Box of Daylight, 36; Brown in Abbott, The Spirit Within, 234; Fognell and Marr, Art of the North American Indians, 339. Special thanks to Bill Holm, Steve Brown, and Mary Malloy for input into this aspect of the research for this essay.

- Collison and Bunn-Marcuse, “Gud Gii AanaaGung: Look at One Another.”

- The mask collected by Hunt is AMNH 16/6887; see Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 174. The related Gusgimaxw narrative is in Boas and Hunt, Kwakiutl Texts, 382-390. At different times, Hunt used the spellings Sepa’xais and Sepa’xalis.

- After receiving the AMNH mask, Boas wrote to Hunt: “First of all, I find that one of the masks, which is undoubtedly a fool-dancer’s mask, is described by you as that of Sepa’xalis who came down from heaven, one of the Koskimo ancestors. I mean that one which I described in the book on social organization of the Kwakiutl Indians. Besides this one, there are a few other which make me suspect that the Indians may try to impose upon you a certain extent in giving explanations of masks and connecting them with the stories that you are writing down.” Boas to Hunt, 3 January 1900, Boas Professional Papers, APS.

- Hunt, “Kwakiutl Materials,” 1909, 1911.

- See Boas, Primitive Art, 279, and Kwakiutl Ethnography, 337.

- Glass, Objects of Exchange, 149-52; https://www.bgc.bard.edu/objects-exchange-mask-18.

- Abbott, The Spirit Within, 234.