CHAPTER X: REPATRIATION

Power Board

Power Board

Unknown maker, Kwakwaka’wakw

Cedar, spruce root, paint, iron, mica, steel

21.7 x 177 in. (55.1 x 449.6 cm)

Collected by Franz Boas in 1889

U’mista Cultural Centre 80.02.001

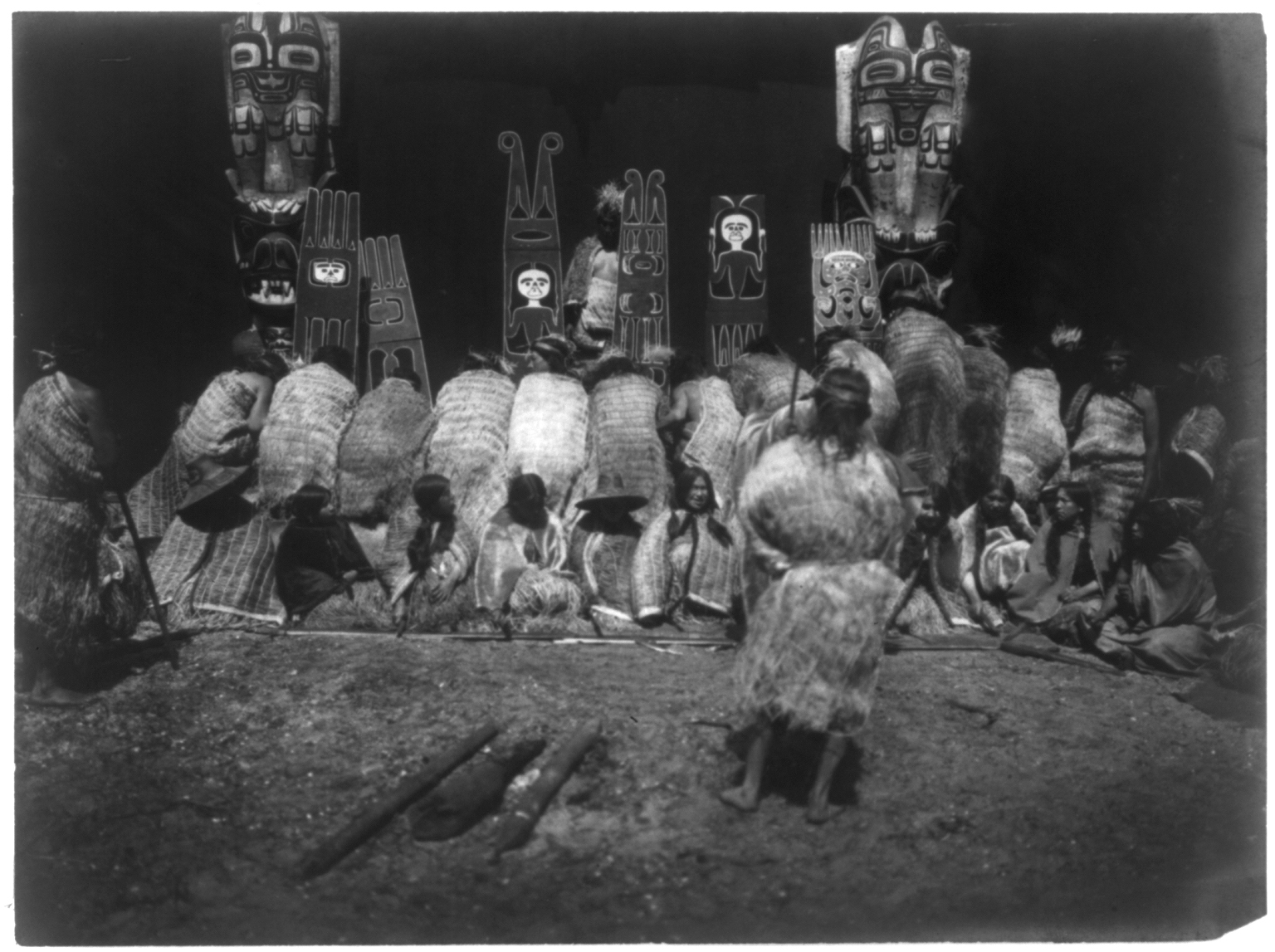

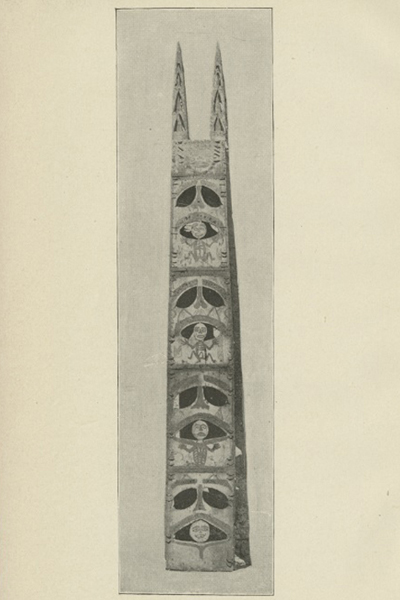

Plate 39 from Boas’s 1897 book.

Hunt’s 1920s notes on plate 39:

yᴇxts!aᵋyo ˰ or

Dᴇnts!ekw ˎ

Danger to Be seen ˰ or ˎ carryed from

wenalā´gᴇᵋles By the toxᵋwet Dancer

Among the Kwakwaka’wakw, power boards (da̱nt̕sikw) appear with some stylistic variation as dance props in both Tuxw’id and Nunłam (or Nułam) performances. Dant̕sikw consist of multiple carved wooden boards hinged together so they undulate, with a snakelike movement, when held up in the air by dancers or when raised by cords suspended over roof beams.1 They are frequently painted and decorated with reflective mica that catches firelight and reinforces their animated appearance.

Ethnographers have provided various explanations for such power boards. In his 1897 text, Boas identifies dant̕sikw in general as theatrical props used during a female Tuxw’id dancer’s performance in the Winter Ceremonials (T’seka). In his 1920s annotation to Plate 39, Hunt notes that dant̕sikw represent powers granted to the Tuxw’id by Winalagalis (the Warrior Spirit).2 Hunt associates the term ya̱x̱t’sa’yu (“danger to be seen”) with the boards, likely because individual Tuxw’id dancers embody various forms of supernatural powers. The dancer might demonstrate her powers by raising her hands, palms facing upward, conjuring spirits or animals—materialized in dant̕sikw or mechanical puppets—from the ground, from behind a dance screen, or from the house rafters.3 In other instances, she might heal herself after grievous injury inflicted by fellow dancers and simulated through the use of fake blood and carved prop heads.4 In the context of the Tuxw’id dance, many power boards feature highly abstracted representations of the Sisiyutł, the two-headed serpent, which is often associated with the power to cause death but also to protect warriors or to revive the dead.5

Other dant̕sikw, typically used in the Nunłam dance, depict ghost-like Nunłamgila spirits as small, white, skeletal figures. Boas suggested that among some families or bands, specific Tuxw’id dancers invoke the Nunłamgila spirits (although he failed to identify them in this particular dant̕sikw, where they are clearly visible).6 Edward Curtis, in his 1914 silent melodrama, In the Land of the Head Hunters, filmed the use of dant̕sikw boards featuring Nunłamgila during a dance sequence that seems to blend aspects of both the Tuxw’id and Nunłam.7 Curtis later described this scene’s subject matter as illustrated in a photographic plate (Fig. 1); he maintains that the boards represent a Tuxw’id’s protective spirits, in this case the “yulhfsáyo” (or “yᴇxts!aᵋyo” as Hunt rendered the word), an underground spirit that kills those who see it.8 However, Curtis also mentions that Quatsino Sound and ’Nak’waxda’xw people (the latter of whom are depicted in his photo plate) perform this as part of their Nunłam dance independent of the Winter Ceremonials—and consequently the Tuxw’id. Today, dant̕sikw are still used in both the Tuxw’id and the Nunłam, which Kwakwaka’wakw consultants describe as two separate dances.9

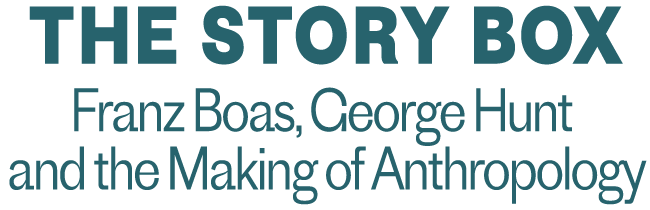

Fig. 1. “An Incident of the Winter Dance – Nakoaktok,” by Edward Curtis. From The North American Indian, Vol. 10: The Kwakiutl (1915), facing page 210. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Edward S. Curtis Collection, LC-USZ62-52222.

It is likely that Boas purchased this particular dant̕sikw —which is unusual in its height—in Alert Bay on his 1889 fieldtrip, and he mentions such boards in general in his field notes from that year.10 Boas then sold it to the Museum of the Geological Survey of Canada, in Ottawa (now the Canadian Museum of History). The power board remained there until 1980 when the museum returned it, on long-term loan, to the U’mista Cultural Centre at Alert Bay in the context of the repatriation of the Potlatch Collection.11 In 2019, just days before the opening of The Story Box at U’mista, the Canadian Museum of History formally transferred ownership of the power board to the U’mista Cultural Centre.

By Leonie Treier

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Boas, The Social Organization, 487, 491-92.

- See also Suttles, “Streams of Property, Armor of Wealth,” 100.

- Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 66.

- Boas, The Social Organization, 491; Suttles, “Streams of Property, Armor of Wealth,” 100.

- Hawthorn, Kwakiutl Art, 29.

- Boas, The Social Organization, 492. It is unclear why Hunt likewise failed to identify the visible Nunłamgila figures in his 1920s notes.

- Holm and Quimby, Edward Curtis in the Land of the War Canoes, 84. See also Evans and Glass, Return to the Land of the Head Hunters, 328.

- Curtis, The Kwakiutl, 210.

- William Wasden Jr. and Trevor Isaac, personal correspondence. Thanks also to Judith Berman for linguistic insight into the various Kwak̓wala terms discussed here. It seems likely that the recorded discrepancies in dant̕sikw use are another example of historic variation in cultural practice across different villages and bands, as well as potential change over the past century.

- Boas Professional Papers, 1889 Notebook #8, 158. Thanks to Rainer Hatoum for translations of the relevant passages.

- National Museum of Man, “Kwakiutl Treasures Returned to Alert Bay, B.C.” (May 18, 1981), accessed through U’mista Cultural Centre Gift Files; see also Knight, “Unpacking the Museum Register,” 43.