CHAPTER VII: POST 1897 AFTERLIVES

Settee Backrest

Settee Backrest

Unknown maker, Kwakwaka’wakw

Wood, pigment, metal

118 x 40 x 5 in. (299.7 x 101.6 x 12.7 cm)

Collected by George Hunt in 1898-1899

American Museum of Natural History, 16/7964

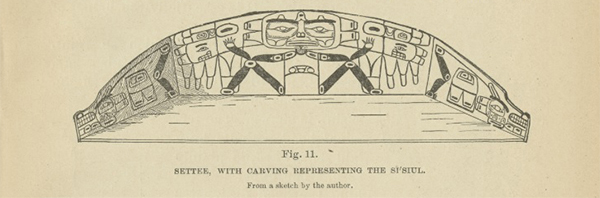

Figure 11 from Boas’s 1897 book.

Hunt’s 1920s notes on figure 11:

sēᵋsᴇᵋyoł´ ts!ᴇᵋwākw te!gāts!ē

Double Headed snake

inside of to lay Down on Back in

this also used By q!alîde family

In the nineteenth century, only wealthy chiefs possessed elaborate settees carved and painted with their hereditary crests, and the sheer scale of this one would have boasted the wealth of its owner when he used or displayed it during potlatches. The backrest displays the prestigious crest of the Sisiyutł, a supernatural double-headed serpent, whose heads were depicted on the seat’s original side panels (as seen in Boas’s book figure). The human face is masterfully carved in relief, and traces of red vermillion trade paint are visible in a hatching pattern along the eyes, on the cheeks, and under the mouth. The thin formlines delineating the body of the Sisiyutł are painted in an Indigenous black pigment derived from magnetite. The backrest shows general signs of wear, indicating that it was frequently used. George Hunt, who purchased this piece for Franz Boas, did not collect the sides as they were made from commercially milled lumber and Hunt knew that Boas only wanted “authentic,” hand-crafted materials.1 The floor plank is also missing, likely for the same reason.2

In Boas’s 1897 book, his own drawing of the settee was used to illustrate the conventions of the Sisiyutł crest motif without any discussion of the object itself. This drawing had been previously published in Boas’s 1888 article, “The Houses of the Kwakiutl Indians,” which suggests that Boas made it in situ on his first 1886 trip to X̱wa̱mdasbe’ (Newitti), on Hope Island.3 His drawing shows the whole settee, including the sides and the floor plank, but Boas missed a few pictorial details in the painted crest motif. In this earlier article, Boas records that the settee was in the house of Chief “Komena’kulu” (K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la), who went by the English name “Cheap” (a derivation of the word “chief”). The front of his house was reportedly painted with a Sisiyutł motif until K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la whitewashed it in order to comply with colonial authorities (Fig. 1).4 In a letter to his parents written from X̱wa̱mdasbe’ after a dance presentation, Boas describes sitting in such a settee—perhaps this very one—with his host family.5

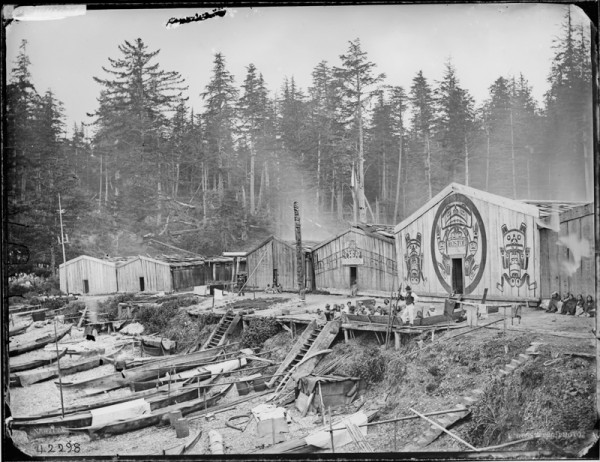

Fig. 1. The Village of X̱wa̱mdasbe’ (Newitti), Hope Island, British Columbia, photograph by Edward Dossetter, 1881. The Sisiyutł crest motif on K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la’s house front, second from the right, is still visible. American Museum of Natural History Library, Image 42298.

As the book was being published in 1897, Boas launched the Jesup North Pacific Expedition from his new curatorial post at the American Museum of Natural History. In January 1898, Boas wrote to Hunt asking him to go to X̱wa̱mdasbe’ in order to acquire the settee and some associated house posts.6 Hunt spent the next two years using his insider position as a cultural broker to facilitate the transaction. From this moment through the 1930s, Hunt consistently reported that the settee belonged to Chief K’alidi, of the Naḵa̱mga̱lisa̱la Band of X̱wa̱mdasbe’, and was used by his family. Yet when Hunt tried to purchase the settee in March 1898, he stated the owner at the time was a man named Ts’ax’id, and that another man named Hamdzid (the grandson and heir of K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la) was actively using K’alidi’s house in X̱wa̱mdasbe’ for the purpose of holding a Winter Ceremonial.7 (It is interesting to note that an earlier house front belonging to K’alidi travelled to Chicago for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.)

Boas’s primary host in X̱wa̱mdasbe’ in 1886 was in fact K’alidi, which raises a number of possible explanations for his placement of the settee in K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la’s house in the 1888 article: K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la owned the settee at the time and transferred it to K’alidi within the next decade before Hunt tried to acquire it; K’alidi already owned it but placed it in K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la’s house for ceremonial purposes, despite the fact that the two men had different primary ’na’mima affiliations; or Boas was simply mistaken in initially associating it with K̠’uma̠’nakwa̠la. Judith Berman, who helped us interpret the archival documentation, suggests that much of the confusion over prerogative ownership in the late nineteenth century stems from the fact that massive population loss from introduced diseases left many hereditary ’na’mima positions empty, resulting in frequent transfer and consolidation of previously discrete chiefly titles and prerogatives across individual, lineage, band, and village lines.

Whoever the actual owner was, Hunt was able to pay for three posts in early 1898, but he could not take possession until the winter season was over. Moreover, the family asked for 50 dollars for the settee, which Hunt felt was too high.8 On March 14, Hunt wrote to Boas that he managed to get the settee’s price down to $8.75 by asking a creditor to call in the owner’s debt so that Hunt could seal the deal.9 Even so, the owner did not deliver the objects for another year, until Hunt increased the pressure in July, 1899.10 The settee and house posts finally arrived at AMNH in January 1900.11

By Shuning Wang and Aaron Glass

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- Hunt to Boas, 24 February 1900, APS; Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 214.

- When Hunt later collected another settee (AMNH 16/8432) for Boas, he again chose not to collect the original floor plank (Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 74).

- Boas, “Houses of the Kwakiutl,” 200, fig. 5.

- Boas, “Houses of the Kwakiutl,” 206; Glass, Objects of Exchange, 198.

- Rohner, The Ethnography of Franz Boas, 40.

- Boas to Hunt, 4 January 1898, APS.

- “Accession File 1900-14.” Archives, Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY; Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 214. It is possible that Ts’ax’id had inherited some of K’alidi’s prerogatives, or that Ts’ax’id was actually a name used by K’alidi himself at the time Hunt inquired about the sale, but this is not clear; we also don’t know the relationship of Hamdzid to K’alidi, such that the former would be using the latter’s house (Judith Berman, personal communication).

- “Accession File 1900-14.” Archives, Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.

- Hunt to Boas, 14 March 1898, APS.

- Hunt to Boas, 4 July 1899, APS.

- Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts, 214.