CHAPTER VIII: POST 1897 COMMERCIAL REPLICAS

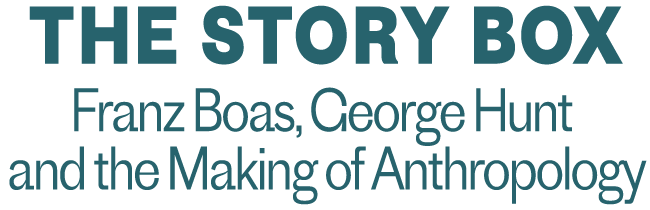

Coppers

Copper

Unknown maker, Tlingit

Copper, pigment

37 x 22 in. (94 x 55.9 cm)

Collected by James Swan in 1875

National Museum of Natural History, E20778

Copper

Unknown maker

Copper, pigment

30 x 21 5/8 in. (76.2 x 54.9 cm)

Collected by George Emmons in 1909

American Museum of Natural History 16.1/404

Figure 3 from Boas’s 1897 book.

No Boas image or Hunt Notes

In 1907, shortly after Franz Boas left the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), collector George Emmons warned the museum’s director, H.C. Bumpus, of a “manufactury” [sic] of prematurely aged replica objects in Skagway, Alaska.1 It is likely that many similar workshops existed but the best documented is Alaskan Indian Curios, owned by Bernard A. Whalen, which produced multiple copies of Tlingit-style masks, rattles, and daggers in copper and other materials.2 Emmons described these as “very beautiful and interesting pieces… wholly of native design, conception & work [which] through a simple process can be aged.”3 Presumably he was warning the museum director about the circulation of such modern replicas, yet two years later Emmons sold just such an object to the museum—a Copper he attributed to the Haida (on the right), which museum records link to an unspecified Alaskan source.4

Correspondence files reveal that Emmons purchased the Copper in the spring of 1909 in Seattle, where he was exhibiting his own Northwest Coast collection in the Alaska Building of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Emmons initially offered to purchase three old Haida pieces for AMNH, but in the time it took for Bumpus to reply only a single Copper was left available.5 Tellingly, perhaps, Emmons did not reveal the specific source of his purchase. Upon close inspection, this Copper is revealed to have been derived from Figure 3 in Boas’s 1897 book, which pictures a Tlingit Copper from the U.S. National Museum collected in 1875 by James Swan in Sitka, Alaska (here on the left).6

Although the specific manufacturing context of the AMNH Copper is still a mystery, there are a number of notable stylistic discrepancies between the earlier Copper and its derivative at AMNH, all of which corroborate the role of Boas’s illustration as the mechanism of replication: two “U-forms” over the large eyes of the earlier Copper have inner, green shapes, which Boas’s sketch and the AMNH Copper lack; the main beak form on the prior example is split into two discrete outlined units, whereas Boas’s sketch and the AMNH Copper feature a single outlined beak form; and although the space between the earlier Copper’s beak and the oval humanoid face below it has painted, diagonal stripes, the equivalent spaces on Boas’s sketch and the AMNH example lack stripes. Curiously, the tonal values of the replica Copper are reversed: whereas the earlier Copper features black formlines on an unpigmented copper field, the designer of the AMNH Copper used black to designate the negative space around copper formlines.

Material evidence further suggests the likelihood that the AMNH Copper was fabricated in the context of commercial production, as Emmons had reported. Portable X-ray florescence revealed its black pigment to be comprised of ferric chloride and selenium, a common European medium of black pigmentation in the nineteenth century, rather than the customary carbon-based agents (such as pitch) used by most Native craftsmen at the time.7 Based on the uniformity of its outline and the precision of its internal, raised “T” structure, the manufacturer of the Copper plaque itself was highly skilled and almost certainly Indigenous.8 However, the engraved motif is quite loose and departs from conventionalized formline designs of the northern Northwest Coast, suggesting that it may have been applied by a different person than had fabricated the form—someone with access to Boas’s 1897 book.

Two other comparative examples clearly derived from Boas’s illustrations indicate a previously unidentified context for Copper replication on the Coast. Between 1910 and 1911, an English antiques dealer named Robert G.R. Piper sold two Coppers to museums in Germany as part of Northwest Coast collections with unknown provenience.9 Like the AMNH example, the Copper now in Munich (Fig. 1) is based solely on Boas’s Figure 3; the one in Frankfurt (Fig. 2) is a composite, with a bottom (spine/rib) field derived from Figure 3 and a top (face) field copied from the Haida Copper pictured in Boas’s Plate 4. Also like the AMNH example, both Coppers in Germany feature copper formlines on a black field and are 75cm. tall, suggesting a common fabrication setting. However, they appear to have been manufactured and engraved by the same (relatively unskilled) person or team as one another, and their irregular outlines and proportions contrast with the skillfully executed form of the AMNH example.10 They are both attributed to the Heiltsuk in museum records, although the basis for that attribution is not clear.

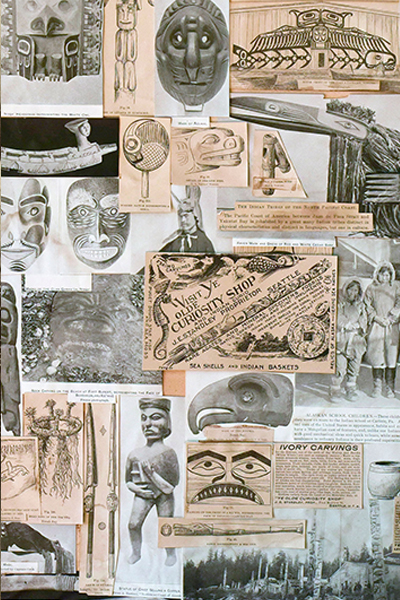

The original sources for both Emmons’ and Piper’s replica Coppers may be unknown, but the historical coincidence of their sales to museums between 1909 and 1911 is noteworthy and might suggest a common point of origin. Since Emmons was in Seattle in 1909, it is possible that he acquired his Copper from Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, which is known to have sold replica objects copied from Boas’s book, in some cases to European collectors. While it is also possible that Joseph Standley had replica Coppers manufactured in Seattle, it is more likely that he would have acquired them from Alaskan sources such as Alaskan Indian Curios, although scholars have not yet traced such Coppers back to any particular “manufactury” per se.11 In any case, the presence of multiple Coppers derived from Boas’s book demonstrates its rapid integration into the world of commercial retail activity on the Northwest Coast, and its lasting—if largely unrecognized—mediation of global ethnographic collections.

By Aaron Glass

PAGES IN THIS CHAPTER

- George Emmons to Hermon Carey Bumpus, 21 July 1907, Folder 59 (1907-08), Central Archives, American Museum of Natural History Library.

- Lenz, “No Tourist Material.”

- Cole, Captured Heritage, 294.

- Jonaitis, From the Land of the Totem Poles, 37.

- Emmons to Bumpus, 11 May and 1 June 1909, Folder 59 (1909), Central Archives, American Museum of Natural History Library. Curiously, Emmons initially sketched and described the available Copper as depicting a bear crest, which is not apparent in the one he eventually sold to the museum. Perhaps he lost out on that sale and substituted another without telling Bumpus. The Copper is the only item in this particular Emmons accession, the records for which contain no additional documentation (Accession #1909-52, Anthropology Division, American Museum of Natural History).

- Swan was commissioned to assemble a large Northwest Coast collection for exhibition by the U.S. National Museum at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, but it is not clear whether this Copper was featured (Cole, Captured Heritage, 19-33). It seems to have been purchased by Swan from Captain Amos T. Whitford, a merchant resident in Sitka, although its origin location is unrecorded (Accession #4730, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History).

- Portable XRF testing conducted by Professor Jennifer Mass, Bard Graduate Center, on February 15, 2018. See also Ancheta, “A Thin Red Line: Pigments and Paint Technology of the Northwest Coast.”

- Bill Holm and Haa’yuups (Ron Hamilton), personal communications.

- Robert Garnet Rayment Piper (1883-1956) was a farmer and antiques dealer in Bishop’s Stortford, UK, although little is known about him. He was not a major supplier to European ethnographic museums, and we have been unable to identify the source of his Northwest Coast collections. It is doubtful that he travelled to the Coast himself, but rather assembled his eclectic and poorly documented collections from other collectors, dealers, or auction houses in the UK. Both Munich (# = ca. 35) and Frankfurt (# = ca. 48) collections feature a combination of ceremonial and quotidian objects, some labelled with specific tribes (primarily from British Columbia) but most simply attributed to “Northwest Coast.” Piper was a lifelong bachelor and left the bulk of his estate to his maid, thereby leaving no direct heirs or traces of what may have been his personal collection or business records. My thanks to Christian Feest for identifying the Piper pieces in Frankfurt, and to Suzanne Nicholls (Hertfordshire Archives) and Leonie Treier for genealogical research on Piper.

- Jopling (“The Coppers of the Northwest Coast Indians,” 108 and Figs. 4, 7, and 10) is the only source I found to have included the NMNH, AMNH, and Munich Coppers in the same publication. Although she acknowledges that the Munich one “imitates” the other two, Jopling erroneously concludes that they might together be among the earliest extant, post-contact Coppers. The Munich Copper was also published in Haberland, Donnervögel und Raubwal, 80.

- We do not know if Standley ever purchased directly from Whalen of Alaskan Indian Curios, but there is evidence that he bought and sold items—including objects made from copper—from other curio stories in Skagway, such as those owned by the Kirmse family and P.E. Kern (Christopher Smith, personal communication).