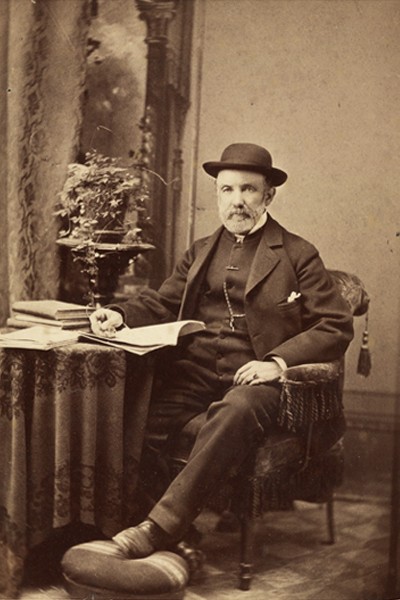

James G. Swan

James G. Swan (1818-1900), one of the first prolific collectors of Northwest Coast Indigenous objects, was born in Massachusetts in 1818. After the California Gold Rush began in 1848, Swan left Boston and his wife and children for the West Coast. As an oysterman in Washington Territory, Swan worked alongside the region’s Native people. He cultivated these relationships to secure a position as secretary to Isaac Stevens, the first governor of the territory. In 1857, Stevens introduced Swan to Spencer F. Baird, the Assistant Secretary in charge of publication and collections for the Smithsonian Institution, who was eager to expand the collection of the nascent U.S. National Museum.

In 1863, Baird began reimbursing Swan for the ethnographic material he collected, and a few years later Swan published a monograph on the Makah for the Smithsonian. Soon after, Swan requested that his position be made official. His local knowledge, he argued, meant that he had a superior understanding of the ethnographic context of the material the Smithsonian was interested in acquiring. With institutional planning underway for an Indian display at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Swan pleaded his case until, just a year before the fair’s opening, he was commissioned to assemble a collection for exhibition.

Swan commenced collecting for the fair with gusto; the first object he acquired was a majestic sixty-foot canoe from Nootka Sound. He then headed north to gather what he believed would be the most spectacular pieces—several large poles from Tsimshian communities where villagers had recently converted to Christianity. Swan’s respect for Native peoples and cultures is reflected in his writing and the breadth of his collecting activity. Unlike many other collectors, he held no prejudice against contemporary work, and he readily purchased silver jewelry, argillite boxes, and unused whaling harpoons.

After the fair closed, Baird scrambled for funds for additional Smithsonian collections. By the 1880s it was clear that the coastal market for Indigenous objects had changed: prices increased when tourist and foreign collectors entered the market. Swan, working for the U.S. Government, had to be creative to continue making meaningful acquisitions. He traveled to Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands) in 1882 as a collector for the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries, and again to gather regional material for the 1884 Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans. After Baird’s death in 1877, Swan found little work as a collector. His last effort was on behalf of Franz Boas for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Several objects collected by Swan for the U.S. National Museum appear in Boas’s 1897 book, including seal dishes, rattles, whistles, and headdresses from the Haida, and a head ring accompanied by Swan’s description of Nuu-chah-nulth ceremonies (in fact, Swan is one of the only authors directly cited by Boas). Swan’s encyclopedic collections provided a variety of comparative, non-Kwakwaka’wakw objects that Boas used to help illustrate his theories of regional variation and cultural diffusion.

By Leela Outcalt

Objects Collected by Swan

SOURCES:

Cole, Douglas. Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1985.

McDonald, Lucile. Swan Among the Indians: Life of James G. Swan, 1818-1900: Based upon Swan’s Hitherto Unpublished Diaries and Journals. Portland, Or.: Binfords & Mort, 1972.

Oldham, Kit. “Swan, James G.” Historylink.org, Essay 5029, 2003; updated 2015. https://historylink.org/File/5029 (Accessed April 27, 2019).