Ceramic manufacturing in the nineteenth century was labor-intensive and involved many workers with different skills. A completed piece may have passed through as many as twenty processes, each one carried out by a different person or team. The machinery that was used was often powered by hand or foot rather than by steam. Pottery factories, rarely purpose-built, were usually arranged to form one or more courtyards with the ovens or kilns in the middle. Even if water was accessible, sanitary facilities were rarely provided for the workers. Coal for firing would be stored in the yards, alongside the defective wares for disposal, and crates of finished goods for dispatch. The result was usually an inefficient layout with cramped, hot, airless, and dirty working conditions.

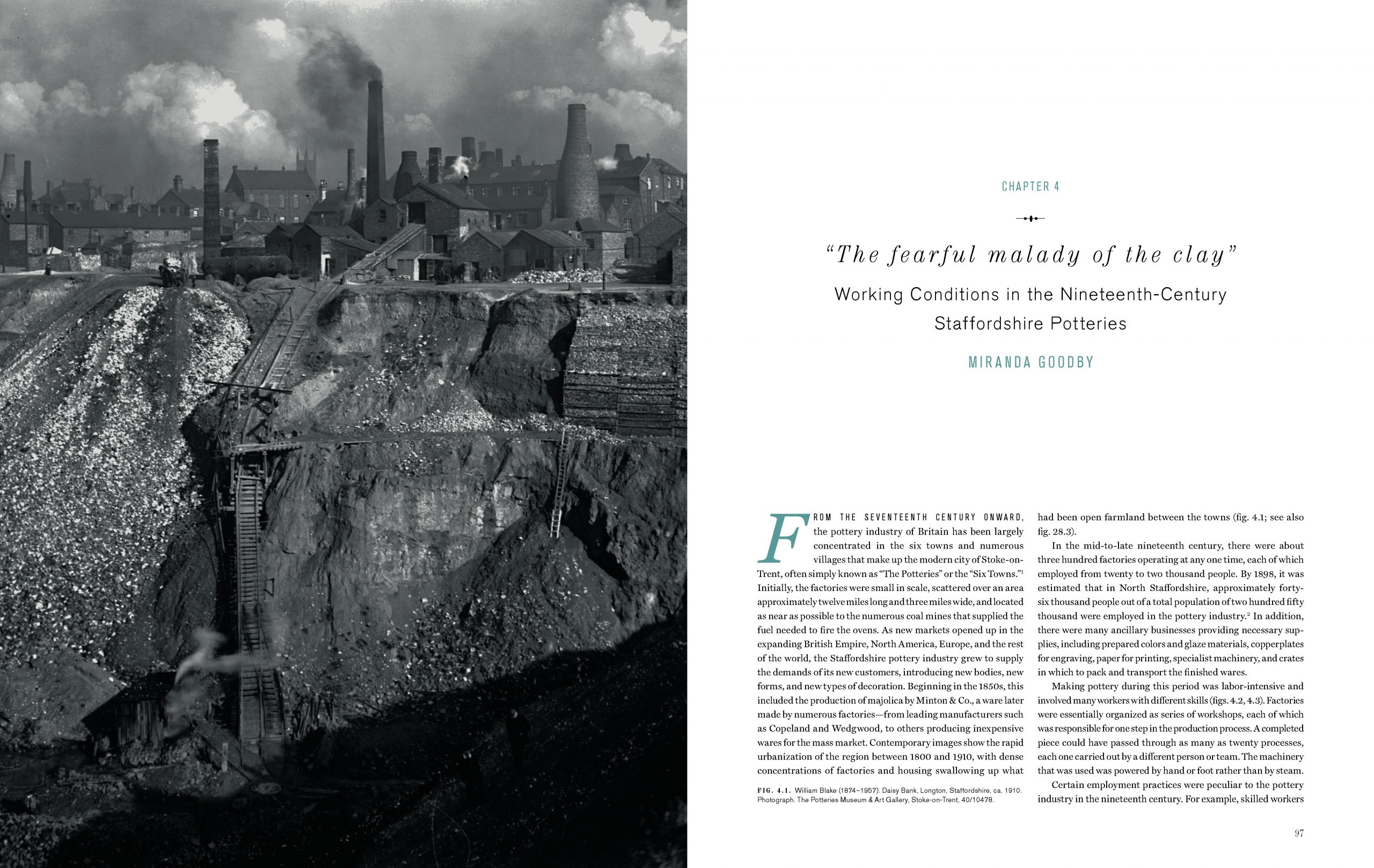

Pottery in this period was fired with coal. There were almost one thousand ovens or kilns firing on a weekly basis in “The Potteries,” the six towns and numerous villages that make up the modern city of Stoke-on-Trent, the main center for ceramic production in nineteenth-century Britain. Like most industrial centers of the Victorian period, the area was permanently wreathed in smoke, which filled the air as well as the lungs of its residents. For the pottery workers, however, dust was an additional and even worse hazard—cited as “the greatest enemy to the health of the operative.”

Production Process

Majolica was made from an earthenware body and finished with colorful lead-based glazes. The ceramic was relatively inexpensive to manufacture given that it could be mass-produced in a factory setting, decorated by relatively unskilled painters, and typically required only two firings. Most majolica was produced using molds—the earthenware body, while somewhat porous and less glasslike than other clay bodies, is quite robust and thus was suitable for making sculptural forms. Once the molded clay dried, any flaws or seams were removed. The object was then fired in a ceramic oven or kiln. After the first firing, the resulting “biscuit” ware was hard but still porous. Workers, often female “paintresses,” applied the glazes, which were liquid mixtures of high amounts of lead and other minerals. When fully dry, the ware would be fired a second time, chemically transforming the glaze into a colorful, glossy surface that is both permanent and water-resistant.

John Thomas Grice (ca. 1872–1946), maker

ca. 1890–1910

Fire clay, metal, wood, textile, and glass

The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, 1979P34

Ovens or kilns such as the one depicted in this model, known as “bottle” ovens for their distinctive shape, were the primary type used in pottery manufacture during the nineteenth century. Ceramic wares, usually placed in protective fireclay boxes called saggars, were loaded into the upper part. Once the kiln was sealed, coal was burned in the furnace at the base, and the resulting heat transformed the clay bodies and glazes into their final forms.

In the early 1870s, Léon Arnoux (1816–1902), art director at Minton & Co., designed a new type of oven that used less fuel and held a more consistent temperature than traditional models. His innovation gave the firm a significant advantage over its competitors.

John Thomas Grice (ca. 1872–1946), maker

ca. 1890–1910

Fire clay, metal, wood, textile, and glass

The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, 1979P34

Ovens or kilns such as the one depicted in this model, known as “bottle” ovens for their distinctive shape, were the primary type used in pottery manufacture during the nineteenth century. Ceramic wares, usually placed in protective fireclay boxes called saggars, were loaded into the upper part. Once the kiln was sealed, coal was burned in the furnace at the base, and the resulting heat transformed the clay bodies and glazes into their final forms.

In the early 1870s, Léon Arnoux (1816–1902), art director at Minton & Co., designed a new type of oven that used less fuel and held a more consistent temperature than traditional models. His innovation gave the firm a significant advantage over its competitors.

Left

Shell, shape no. 1182

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1862–65; this example 1868

Glazed porcelain

Nicolaus Boston, London

Right

Shell, shape no. 1182

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1862–65; this example 1865

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Right

Shell, shape no. 1182

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1862–65; this example 1865

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Joseph Holdcroft, Longton, Staffordshire

ca. 1880s

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Aviva and Gerald Leberfeld

Pottery manufacturers in the second half of the nineteenth century often produced more than one ceramic type, such as earthenware and porcelain, and then used various finishes and embellishments to further diversify their products. Indeed, Minton, offered many of the models it manufactured in majolica, such as the polychrome-glazed centerpiece shown above, in other ceramic bodies—including a version that features a white-and-green porcelain body beneath a clear glaze. The Joseph Holdcroft dessert plates on the left highlight the options that could be realized through varying the combinations of majolica glazes applied to an earthenware body.

Léon Arnoux (1816–1902) and others for Minton & Co.

ca. 1850–1906

Pen-and-ink on paper in bound volume

Minton Archive, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1705/MS1430

Léon Arnoux (1816–1902) and others for Minton & Co.

ca. 1850–1906

Pen-and-ink on paper in bound volume

Minton Archive, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1705/MS1430

The formulation of a successful glaze required the skill of a trained chemist to correctly balance the various components—silica (a form of glass), metal oxides for color, flux, and other ingredients—in order to produce the intended finish. Experimentation was critical to the process, as was consistency. Majolica glaze recipes, recorded in notebooks such as this one from the Minton company archive, were part of the intellectual property of the manufacturer and highly prized throughout the trade. Léon Arnoux, the firm’s longtime art director, had a particular gift for glaze creation and formulated many of its most distinctive finishes. Most of the recipes in this notebook are in his hand, recorded in French, and often in a shorthand peculiar to the pottery industry. The recipes on the pages shown here include several for “Palissy” ware, an early Minton trade name for majolica.

The Potteries: Workers and Working Conditions

Ceramic manufacture in the nineteenth century was labor-intensive and involved many workers with differing skills. A pottery factory was essentially organized as a series of workshops, each responsible for one step in the production process—from preparing the clay and molding the shapes to glazing the wares and loading the kilns. Much of the work was done by hand, and most trained potters relied on teams of assistants to carry out tasks that did not require expertise. Until the introduction of compulsory education in the 1870s, children were a source of cheap labor. Most entered the trade by age eight—sometimes even younger—and they typically toiled between twelve and fourteen hours a day. Children were expected to fetch and carry, prepare raw materials, and to power the limited machinery used by the potters. These were physically exhausting tasks and typically exposed the children, like many pottery workers, to toxic levels of dust and smoke, and to extreme temperatures.

By far the most harmful substance found in the potteries of this period was the raw lead in glazes. Majolica glazes, in particular, were typically 40 to 60 percent lead. When ingested, absorbed through the skin, or breathed in as a dust, this heavy metal accumulated in the body, where it caused lead poisoning and an associated range of ill effects, including death. Majolica glazes were usually painted on rather than dipped, and this work was invariably done by women and girls known as “paintresses.” As the colorful earthenware gained in popularity and thus was made by more factories, the number of paintresses exposed to the high concentrations of lead increased accordingly. Reforms and regulations imposed by the British government beginning in the 1890s gradually improved conditions for pottery workers, including limiting the use of lead in manufacture.

From Cup and Saucer Land, by Malcolm Graham (London: Madgwick, Houlston and Co., Ltd., 1908). Bard Graduate Center Library, New York.

From Cup and Saucer Land, by Malcolm Graham (London: Madgwick, Houlston and Co., Ltd., 1908). Bard Graduate Center Library, New York.

Thomas Aidney, color manufacturer, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

1883

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Gladstone Pottery Museum, Stoke-on-Trent, STKGP.1980.755B

This plate shows a range of glaze colors produced by a specialist color maker—one of the many ancillary trades that supported majolica manufacturing. The lead content of majolica glazes was typically 40 to 60 percent as compared to other types of earthenware glazes, in which it was 14 to 33 percent. The thick, highly glossy, rich polychrome finish produced by this high concentration came at great cost: lead exposure posed serious health risks to those who worked with the unfired glazes at the decorating end of the manufacturing process.

Read More

Working Conditions in the Nineteenth-Century Staffordshire Potteries

Miranda Goodby

Miranda Goodby

Makers’ Marks

Marking the underside of a piece of pottery or porcelain with the name, initials, or symbol of its maker or manufacturer is a centuries-old practice. The American firm of Griffen, Smith & Hill Co. began majolica production in 1879, and its workers often impressed the wares with stamps such as the ones below. The mark most frequently used by the pottery bears the trade name “ETRUSCAN MAJOLICA” encircling a monogram of the interlaced letters “GSH”—the initials of the last names of the firm’s original partners: Henry and George Griffen, David Smith, and William Hill. The firm also used a less elaborate stamp, which rendered the impression of the monogram alone, an example of which is visible on the Covered Cheese below.

View Slideshow

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby