The rise of majolica corresponded with the development of broad-based consumerism, driven by large-scale manufacturing coupled with new marketing initiatives—including retail sales through department stores, along with illustrated trade catalogues and print advertisements. In addition, expansion of rail systems and steamship transport led to greater availability of consumer goods throughout Great Britain and the United States. By this time, a chain of trade had developed to connect manufacturers with the expanding global markets. Many firms had agents in major cities that acted as wholesale sales representatives for their associated factories. Retail relationships had also been established to deal directly with clients. Some, such as the high-end London outlets of Thomas Goode & Co. of South Audley Street and John Mortlock of Oxford Street, insisted on restrictive agreements with factories and, in some cases, held exclusive rights to specific designs.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, international exhibitions were important marketing opportunities for the firms that mounted displays, which typically generated media coverage. The already substantial majolica trade in the United States was given additional stimulus by Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition of 1876, at which large displays of British majolica were on view for the fair’s nearly ten million visitors. American enthusiasm for majolica was built on an existing taste for the ware, which had been fostered during the late 1860s and early 1870s by prominent retailers and wholesalers located in the major metropolitan centers along the East Coast.

International Exhibitions

Minton & Co. introduced majolica in an elaborate display at the Great Exhibition of 1851, a grand spectacle held in London that brought together an array of art, design, industrial products, machines, and raw materials from around the globe. This was the first in a succession of international exhibitions held in cities worldwide. Attracting millions of visitors, these prodigious fairs lasted between three and six months, and served as critical venues for the debut and promotion of new goods. Majolica made by Minton and other manufacturers would be featured in international exhibition displays for the remainder of the nineteenth century.

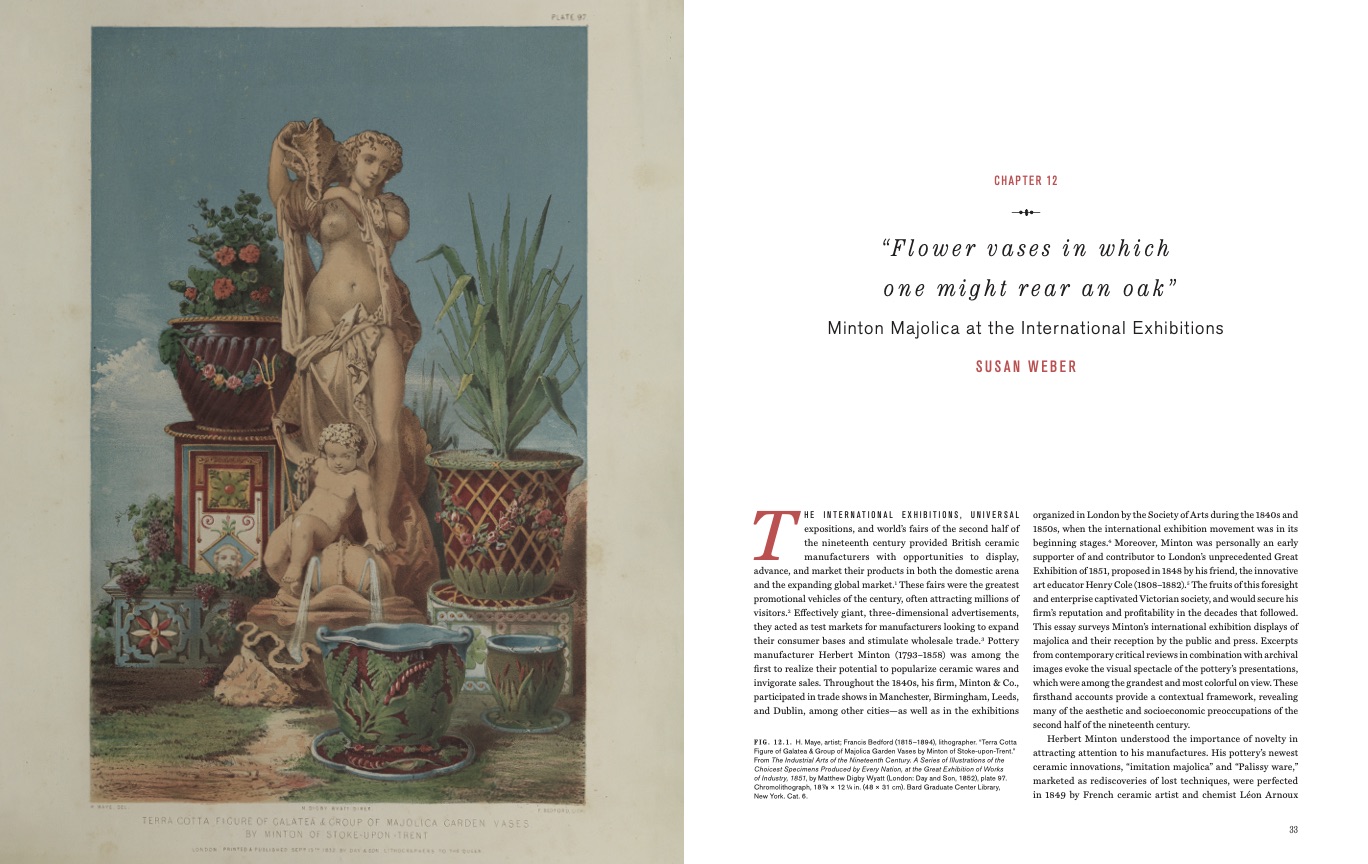

Plate 97 from The Industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century: A Series of Illustrations of the Choicest Specimens Produced by Every Nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry, 1851, by Matthew Digby Wyatt

H. Maye, artist; Francis Bedford (1815–1894), lithographer

London: Day & Son, 1852

Chromolithograph

Bard Graduate Center Library

This print records some of the objects shown by Minton & Co. at the Great Exhibition: a terra-cotta fountain as well as a selection of colorful majolica garden pots. The firm’s majolica was met with immediate public approval, captivating visitors and critics alike with its bright glazes and boldly modeled forms. At the close of the exhibition, Minton received the fair’s highest honor, the coveted Council Medal, for its innovation in ceramics.

Click the garden pots illustrated here to see examples of the models shown at the Great Exhibition.

Carlo Marochetti (1805–1867), designer; Minton & Co., manufacturer. Ramshead and Festoon Garden Pot and Stand, shape no. 727, designed ca. 1851; this example 1878. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 13 ⅞ × 16 ¼ × 13 ¾ in. (35.6 × 41.5 × 35 cm). Joan Stacke Graham Collection. Photo: Bruce White.

Click Objects Above to Explore

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1851; this example 1866

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

This exuberant model was among a group of Minton’s earliest majolica designs, several of which take their inspiration from the natural world—in this case, English woodland or garden flora. Only two years after examples of this garden pot and stand were shown at the Great Exhibition, the model was displayed in the first American world’s fair, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, held in 1853–54 in New York City. Minton manufactured this particular design for more than thirty years.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1851; this example 1866

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

This exuberant model was among a group of Minton’s earliest majolica designs, several of which take their inspiration from the natural world—in this case, English woodland or garden flora. Only two years after examples of this garden pot and stand were shown at the Great Exhibition, the model was displayed in the first American world’s fair, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, held in 1853–54 in New York City. Minton manufactured this particular design for more than thirty years.

Plate 97 from The Industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century: A Series of Illustrations of the Choicest Specimens Produced by Every Nation, at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry, 1851, by Matthew Digby Wyatt

H. Maye, artist; Francis Bedford (1815–1894), lithographer

London: Day & Son, 1852

Chromolithograph

Bard Graduate Center Library

This print records some of the objects shown by Minton & Co. at the Great Exhibition: a terra-cotta fountain as well as a selection of colorful majolica garden pots. The firm’s majolica was met with immediate public approval, captivating visitors and critics alike with its bright glazes and boldly modeled forms. At the close of the exhibition, Minton received the fair’s highest honor, the coveted Council Medal, for its innovation in ceramics.

Click the garden pots illustrated here to see examples of the models shown at the Great Exhibition.

Robert Dudley, lithographer; Illustrated London News, publisher

Supplement to the Illustrated London News, August 30, 1862

Chromolithograph

Private collection

Minton’s magnificent St. George Fountain was a chief attraction of the London International Exhibition of 1862. Intended to highlight the firm’s technical mastery and manufacturing prowess, the thirty-six-foot-tall triumph of art and industry was designed by English architect and sculptor John Thomas (1813–1862), who had previously worked with Minton to create the Royal Dairy at Windsor (learn more in the film Majolica in Architecture). The fountain’s overall design celebrated English national identity. Crowned by St. George, the patron saint of England, killing the dragon, it was inscribed, “For England and for Victory.” Minton presented the stone and majolica edifice to the nation following the exhibition, and it remained on display in London until 1926, when it was dismantled and likely destroyed.

Read More

Susan Weber

Print Advertising

Manufacturers and retailers alike were keen to promote fashionable majolica in print. Advertisements in newspapers and popular magazines appealed to the general public, while those in trade journals targeted a more specialized audience.

Publications such as The Pottery and Glass Trades’ Review (later the Pottery Gazette) and the Crockery and Glass Journal were valuable resources for manufacturers and retailers, providing coverage on innovations and the state of the market, as well as intra-trade editorial promotion and advertising. Many majolica makers ran simple text advertisements while others promoted their wares with more elaborate, illustrated announcements. Firms advertising in trade journals were frequently treated to more editorial coverage than those opting not to advertise. These write-ups often include detailed reviews of new products and designs as well as trade reports, and would have provided critical exposure to highlighted businesses. Printed catalogues (with and without images) and illustrated pattern sheets were also important promotional tools used by potteries on both sides of the Atlantic.

Color supplement to the Pottery Gazette, April 2, 1883, between pages 364 and 365. The British Library, London, LOU.LD162.

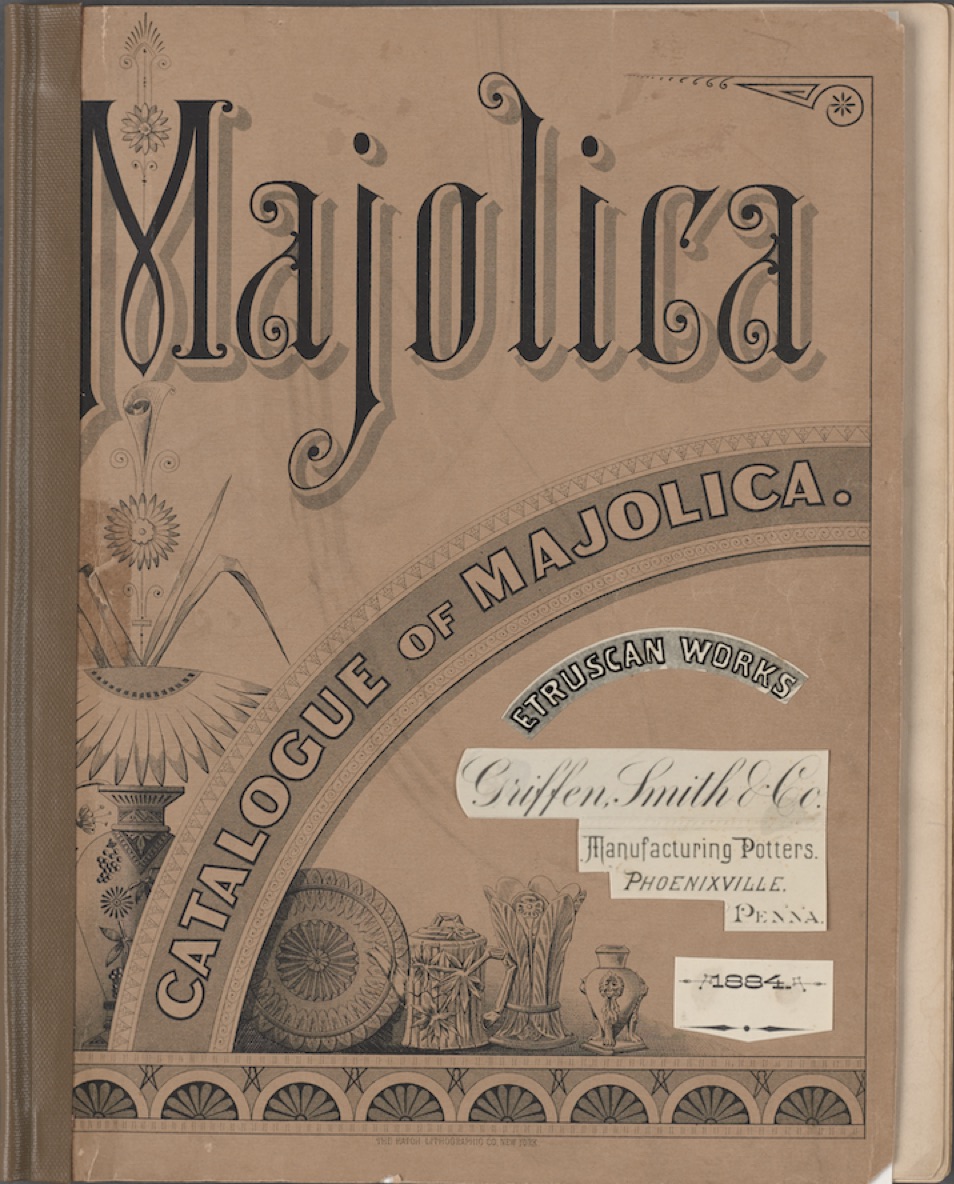

Hatch Lithographic Co., New York, New York

Before 1884

Printed pamphlet

Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area, Pennsylvania

This publication is one of the few illustrated catalogues of majolica ever released by any manufacturer—British or American. Its eleven pages feature color images of 136 majolica models, each with its own individual letter-and-number shape designation. These identifiers can be cross-referenced with a wholesale price list that includes the corresponding pattern and shape names. The catalogue, produced by Hatch Lithographic Co., a renowned New York printer of the period, is lavishly illustrated, thoughtfully designed, and testament to Griffen, Smith & Co.’s ambition within the US ceramic trade.

Flip Through the Catalogue

Hatch Lithographic Co., New York, New York

Before 1884

Printed pamphlet

Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area, Pennsylvania

This publication is one of the few illustrated catalogues of majolica ever released by any manufacturer—British or American. Its eleven pages feature color images of 136 majolica models, each with its own individual letter-and-number shape designation. These identifiers can be cross-referenced with a wholesale price list that includes the corresponding pattern and shape names. The catalogue, produced by Hatch Lithographic Co., a renowned New York printer of the period, is lavishly illustrated, thoughtfully designed, and testament to Griffen, Smith & Co.’s ambition within the US ceramic trade.

D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland

ca. 1882–86

Glazed earthenware painted in enamels and gilding

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Chesapeake Pottery manufactured a number of promotional models for other companies to use as giveaways. Spaulding & Merrick of Chicago offered this covered jar made by Chesapeake to customers who bought its Sunny Bank brand tobacco. While not technically majolica—the colored decoration here was applied with overglaze enamels—these jars were advertised as “beautiful Majolica Vases” and “A THING OF BEAUTY” on Spaulding & Merrick’s trade card promoting what was a “limited time” offer.

Retailers

As populations grew and middle-class wealth increased, manufacturers benefited from new markets. Luxury shops, general retailers, and department stores all played their parts as intermediaries between majolica makers and customers. Retailers enriched manufacturers, while offering symbols of status to their own clienteles. Beyond serving the upper classes, leading London ceramic and glass sellers played a significant role in the early promotion and sale of majolica to the middle classes, as this large consumer group continued to gain both wealth and prestige during the period. While the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 led to widespread awareness of English majolica in the United States, the ware was already available from retailers in major East Coast cities in the preceding decade.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1862; this example 1865

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

View Slideshow

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1862; this example 1865

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

One significant American outlet for Minton majolica and European ceramics more generally was the enterprising retailer Tiffany & Co. (founded 1837), which built a prestigious new store in 1870 at the corner of 15th Street and Union Square West in New York City. An 1875 report in Appletons’ Journal notes:

There are few more varied and attractive places in New York for the art-lover than Tiffany’s store on Union Square. . . . Here are the choicest selections of porcelain from every manufactory in Europe. Here are the most lovely Sèvres and specimens of the finest Dresden ware. Wedgwood vases of dark and light blue. . . . Vases, jugs, pitchers, and other household utensils, appear grouped by themselves, and there is a large and very varied collection of the most interesting kind of new English pottery, the Minton ware. Chinese, Japanese, and majolica, besides other varieties, are arranged separately; and in the new patterns, as well as in the modern reproductions of antique forms.

The Appletons’ Journal account and the photograph of the Tiffany & Co. showroom in the slideshow above demonstrate how majolica was incorporated into a vast and diverse array of novel ceramics and glass from Europe and the United States. This “interesting kind of new English pottery” had to fight for attention on overstacked tables and shelves, in what was literally and figuratively a crowded marketplace. The 1889 photograph of the Minton showroom also shown in the slideshow reveals a comparable, if slightly more orderly arrangement, which features the firm’s majolica masterworks, including the life-size peacock, along with tea sets, vases, and other domestic wares.