About this guide

The Majolica Mania Educator Guide features six lesson plans that highlight themes presented in the exhibition. Our object-based approach and educational framework engages young learners to see deeply, think critically, and build freely. We invite you to use and adapt the lesson plans and activities with your students in your physical or virtual classroom. We hope this guide will deepen your students’ appreciation and investigation of objects.

Please share your experiences with us! Send your feedback and photos of your students and their work to public.programs@bgc.bard.edu.

Mission

Bard Graduate Center is a catalyst for deep reflection with objects; we build dialogue and imagine new ways of seeing.

Vision

Bard Graduate Center is committed to forming the next generation of museum educators, curators, and historians, who see deeply, think critically, and build freely.

Values

See Deeply – We believe in the power of careful observation, deduction, and research. We also acknowledge that audiences bring a wealth of personal knowledge, history, and insight to their relationship to objects.

Think Critically – We value serious, disciplined thinking that is clear, open-minded, and informed by evidence. We want audiences to feel confident about drawing meaning from objects, familiar and unfamiliar. We believe in open dialogue and big questions.

Build Freely – We provide opportunities for people to build relationships and share insights. We hope to build an intergenerational movement of curators, scholars, historians, and visitors, in order to create democratic museums. We believe by reimagining the past we can build an equitable future.

Grades 1-3: Identity, Conformity, and Personal Objects

The expansion of the middle class during the Victorian period (1830s–1901) gave many British families greater access to disposable income and purchasing power. Majolica captured the imagination of middle-class families; it was a whimsical, colorful, and relatively inexpensive home adornment. Though decorative, many majolica wares were also useful, and their form or subject matter often hinted at their intended purpose. By choosing these objects, an individual could show they were aware of the latest fashions, yet had the sophisticated taste to choose the right majolica objects. The power of popular trends continues today, influencing our personal tastes, our ability to show off, and our choice to either stand out or fit in.

Paul Comoléra (1818–1897), designer

Minton & Co., manufacturer

Jug, shape no. 1924, design registered 1874; this example 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

9 ⅞ × 8 ¼ × 4 ⅜ in. (25 × 21 × 11.1 cm)

Impressed marks: MINTONS // 1924 // cipher for 1875 // two illegible marks; molded mark: illegible British registry diamond [for October 10, 1874, parcel 4]

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Joseph Holdcroft

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

11 × 8 × 5 ⅜ in. (28 × 20.1 × 13.6 cm)

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Joseph Holdcroft

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

11 × 8 × 5 ⅜ in. (28 × 20.1 × 13.6 cm)

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Essential Question

How do we use objects to express our identities?

See Deeply

- Look closely at both the pug dog figure and the cat jug. What do you notice? What details can you see?

- Imagine touching or holding these objects. What do you think they would feel like in your hand? How might they compare to touching a real dog or cat?

- How are the two objects similar? How are they different?

Think Critically

- Where in someone’s house do you think they might keep these objects?

- How might they use them?

- Why might someone buy objects like these?

- The designer of the jug modeled it from his own cat! What pet or possession might you make into a sculpture to display? Why?

Build Freely

- Think about your favorite objects at home. How do you choose which objects decorate your room?

- Objects made from majolica, the type of pottery used to make the cat and pug, were very popular in nineteenth-century Britain and America. A lot of people wanted to buy them. Have you ever wanted to buy something that was very popular? What made you want to own it? If not, did you buy something else instead? What was it?

- Do you own anything that is unique to you? How does it make you feel to own it?

Activity

A Sculpture About You

By looking at the pug figure and the cat jug, we have talked about how we can use objects to show who we are. How might you make an object—functional or decorative—that tells others something about you? What is something about you that you would like to display?

Materials

- Wooden, cardboard, or styrofoam squares to use as a base or pedestal

- Model Magic, air-dry clay, or homemade play dough

- Markers

- Decorative materials such as feathers, pipe cleaners, or beads

Instructions

- Think about yourself – your favorite hobbies, something you are proud of doing, or an aspect of your personality. Choose one as the subject of your sculpture. Discuss with a classmate or an adult near you: How can you represent that part of yourself? For instance, I love to look at birds in the park! I might make a sculpture that looks like my favorite bird, or the binoculars I use to watch birds.

- Shape your modeling material into the form you chose, and press it to your sculpture base. Use decorative materials to enhance your sculpture and make it unique to you. Color, texture, and shape can help share your feelings about your sculpture. You might want to decorate your pedestal, too!

Reflection

Share your sculpture with your classmates.

- What did you choose to sculpt?

- How did your materials help share your feelings about your subject?

- Where in your house would you display your sculpture and why?

Grades 4-5 (ELL): Journeys of Objects and People

Immigration and Majolica

This pedestal demonstrates the extent to which majolica was an international phenomenon in the late nineteenth century. Created in the New York City factory of James Carr, an immigrant from England, this object uses the majolica medium, first developed in Britain, and applies it to an iconic American subject, George Washington. The imagery on this object mimics that of the Revolutionary War-inspired painting Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze, himself a German immigrant to the United States. As such, this object raises timely questions about immigration and American identity, and serves as an example of the power of cultural hybridity.

W. H. Edge (1835–1890), modeler (attributed); James Carr’s New York City Pottery, manufacturer

1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

24 × diam. 14 1/2 in (61 × 36.8 cm)

Unmarked

Bryce Smith

W. H. Edge (1835–1890), modeler (attributed); James Carr’s New York City Pottery, manufacturer

1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

24 × diam. 14 1/2 in (61 × 36.8 cm)

Unmarked

Bryce Smith

Essential Question

How do immigrants blend their old and new cultures?

See Deeply

- Look closely at this object’s shape, colors, and design. What stands out to you?

- If you could touch this object, what do you think it would feel like? Would it be soft or rough? Cool or warm? What do you see that makes you say that?

- Describe the figures shown in the detail image. Where could they be? What are they doing? What might they be feeling?

Think Critically

- Looking at the scene of George Washington and his soldiers, what do you think happened right before this moment? What might happen next?

- What are some reasons why the artist, as an English immigrant, might have chosen to include this moment in American history on his artwork?

Build Freely

- Imagine you are on the boat in this image. Which figure would you most like to be and why? Try taking this figure’s pose.

- This object is called a pedestal, or an object that usually holds up a sculpture. Think about the kinds of objects that you have in your home or community. Which of these objects would you choose to place on top of this pedestal, and why?

Printed inscription: Centennial Photographic Co. Philad’a. / International Exhibition, 1876

Stereograph

Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 93516795

Activity

Journeys: Past, Present, and Future

Choose an option from each of the two following steps to create a thoughtful and nuanced creative writing activity for your class.

Step 1

- Option 1: Think of a time when you have gone on a journey or begun something new. This might be a time when you moved to a new place or school, or started something else that was new to you. Write out responses to the following questions:

- How did you prepare for the change?

- What did you bring from the old place to the new place? This could be objects, hobbies, information that you knew, or anything else!

- What changed in your life after the journey?

- Option 2 (recommended for older students): Identify an immigrant in your own life, and interview them about the journey they took. Ask them the following questions and write down their responses:

- How did you prepare to move?

- Can you show me an object that you brought with you on your journey?

- Why did you choose to take it with you?

- Where did you keep it in your old space, and where do you keep it now?

- How do you keep in touch with your former culture while living in a new culture?

- What has changed in your life since you emigrated?

Step 2

- Option 1 (recommended for English Language Learners): Based on the details of your own story or the story of an immigrant that you interviewed, create a comic strip depicting three scenes of the journey: (1) before the journey, (2) during the journey, and (3) after the journey.

- Option 2: Think about a journey that you will take in the future (for example, starting middle school). Based on the lessons learned from your own story or the story of an immigrant that you interviewed, write a letter of advice about this journey to your future self. Include suggestions about how you should prepare, what to take with you, and what kinds of changes to expect. After you’ve finished, ask a teacher or family member to hold onto the letter and give it back to you when your journey is about to begin!

Resources

- Painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware (Emanuel Leutze, 1851) and a New York Times article about a contemporary reinterpretation by Cree artist Kent Monkman

- “Important to Emigrants” (figure 6) from The Potters’ Examiner and Workman’s Advocate, November 2, 1844

Grades 6-8: Advocacy for All Ages

Majolica pottery production flourished in late nineteenth-century Britain and the United States due to mass-manufacturing processes introduced during the Industrial Revolution. In order to meet growing consumer demand, British factories that made majolica employed children to fill a number of roles involved in manufacturing the whimsical ceramics. Unfortunately, long hours, unsafe conditions, and a lack of access to regular schooling characterized child laborers’ experiences. In addition, the materials and by-products used to produce majolica ware, including lead, which was a key ingredient in majolica’s characteristically brightly colored glazes, clay dust, and fumes from the kilns, endangered the health of all workers. Many children suffered from lead poisoning and lung-related illnesses from these materials, and many risked injury in the factory. While the British House of Commons commissioned Dr. Samuel Scriven to investigate child labor in the pottery industry in 1842, these young workers only began to receive partial protections under new laws beginning in 1862.

While children in many countries today are legally protected from mistreatment, advocacy is still needed to promote healthy and safe living environments. Advocacy is activity that supports a cause, usually one a person is passionate about. Today, not only adults but young people are advocates for important issues. What causes are important to you?

Pierre-Émile Jeannest (1813–1857), designer;

Minton & Co., manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1851, this example ca. 1855–60

Earthenware with majolica glazes

24 5/8 × diam. 16 3/8 in (62.5 × 41.6 cm)

Unmarked

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn Karmason

Pierre-Émile Jeannest (1813–1857), designer;

Minton & Co., manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1851, this example ca. 1855–60

Earthenware with majolica glazes

24 5/8 × diam. 16 3/8 in (62.5 × 41.6 cm)

Unmarked

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn Karmason

Essential Question

What is the role of children in a complex society?

See Deeply

- Look closely at this object. What colors, textures, and details stand out to you?

- How would you describe the scene depicted here?

- What feelings do you associate with this scene?

- This object can potentially hold something. What would you place inside?

- Where might you put this object in a home? What does that room look like? Smell like? What activities would take place in that space?

Think Critically

- How do you think this object was made?

- Who do you think made it?

- Given the playful roles children play in this object’s imagery, how might the idea that a child worker could have helped create it, under potentially dangerous working conditions, affect the way you see it?

Build Freely

- At this time, child laborers had very little power to change their working conditions or contribute in a meaningful way to the design of majolica objects. If a child laborer could have designed this object, what might be different about its appearance?

- Imagine you are a worker in a busy factory, where you work 12 hours a day, six days a week. How might your life be different than it is today?

- Where do we see child labor today? Is it directly connected to our lives?

View Slide Show

Activity

Speak Out! Design a Protest Poster

How can you use art to advocate for an issue that affects children? Lead continues to endanger children and their families in America. Watch this video about 13-year-old Mari Copeny, aka “Little Miss Flint,” and her advocacy for protections from lead poisoning in her hometown of Flint, Michigan. As a class, discuss: What is activism and why is it important?

- Paper and/or poster board

- Pencils and markers

- Paint and brushes

- Magazines and newspapers

- Glue

- Scissors

You Can Be an Advocate Too!

Create a Protest Poster Using Symbols and Imagery.

- What are you passionate about? Why is it important to you? What do you think people need to know about it?

- What do you envision when you think of your issue? Sketch symbols and imagery related to it.

- Draw a sketch of your protest poster. How can you arrange symbols and images, and words, to convey your message effectively? Paint or collage your protest sign.

- Stage a peaceful protest in your school or neighborhood and advocate for the issues that are important to you and your community!

Writing Supplements

- Write a letter to a local politician about your issue. Why is it important to you? How should the government help its constituents?

- Write a description of the protest sign you designed and how it represents the issue you chose. Why did you choose those symbols? What does it mean to you?

Additional Resources

Flint: Everything You Need to Know

Vox Three-Minute Explanation

Flint Protests and Timeline

Ten Ways Youth Can Engage in Activism

Scriven’s Report on Child Labour in the Pottery Industry in 1840

Children’s books about activism

-

- Click, Clack, Moo, Doreen Cronin Read Aloud

- A is for Activist, Innosanto Nagara Read Aloud

- What a Citizen Can Do, Dave Eggers Animated Trailer

Grades 7-8: Inspiration and Appropriation

Cultural Influence Across the Globe

Majolica captures the human imagination with its wild designs, but what are their origins? While some majolica designs were fresh and new, many drew inspiration from the past or other cultures. In these cases, designers appropriated patterns, symbols, and imagery from objects made in other countries. Cultural appropriation takes place when designers borrow forms, symbols, and images from cultures other than their own without understanding and respecting their origins or sharing credit or profits with the original creators. This lesson uses majolica ceramics to dive into questions of cultural appropriation: what it looks like and why it’s important to call it out.

China, 1662–1722

Porcelain with overglaze enamel decoration

4 5/16 x 5 3/4 x 3 1/4 in (11 x 14.6 x 8.3 cm)

Unmarked

Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Alfred and Margaret Caspary Memorial Gift, 1955-50-134a,b

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

5 ¾ × 8 ⅛ × 4 in (14.7 × 20.5 × 10.2 cm)

Impressed marks: MINTON // 2268 // cipher for 1880

The English Collection

China, 1662–1722

Porcelain with overglaze enamel decoration

4 5/16 x 5 3/4 x 3 1/4 in (11 x 14.6 x 8.3 cm)

Unmarked

Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Alfred and Margaret Caspary Memorial Gift, 1955-50-134a,b

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

5 ¾ × 8 ⅛ × 4 in (14.7 × 20.5 × 10.2 cm)

Impressed marks: MINTON // 2268 // cipher for 1880

The English Collection

Essential Question

What is cultural appropriation? Why is it important to identify it?

See Deeply

- Look closely at the two ceramic teapots in this lesson. What do you notice? What similarities and differences can you spot?

- Imagine using these teapots. Where are you? What are the sounds, tastes, and scents around you?

- The teapot with the brown handle and spout was made in Britain more than 100 years after the green teapot was made in China. Which details indicate how the British teapot could have been inspired by the Chinese one?

- Why is it important to know where and when these objects came from?

- Does knowing the origins of each teapot change your impression of either? How?

Think Critically

In an effort to improve British industrial design, forums like the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum) displayed countless objects from foreign countries, including China. Although this Chinese teapot was likely crafted to be sold to European consumers, many other exhibited Chinese objects had been looted from Chinese imperial palaces during the Second Opium War (1860–62), which resulted in British and French colonial gains in China. Displays of Chinese objects in European gallery settings, whether they were meant for export or stolen, broadened European interest in Chinese ceramics and motifs.

- Compare this photograph from the Forbidden City in Beijing with this painting of the Chinese galleries of London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. What do you notice about each space?

- How are Chinese objects displayed in the London exhibition? How does the way they are arranged affect the way European or Western viewers might understand the objects? What could make this display more informative for viewers?

- Imagine you are a majolica pottery designer attending one of these displays, and look at the two teapots again. How might you characterize the commonalities and differences between the two objects? Based on the explanation of cultural appropriation in the introduction to this lesson, can you decide whether this is a case of appropriation or inspiration? What other information do you need to make this determination?

- Where do we draw the line for who can and cannot use art and designs of other cultures? What needs to be done to make this kind of inspiration or borrowing fair?

Build Freely

- Read this article on the colonial pavilions at the Great Exhibition and other world’s fairs and recall that Britain and China’s relationship was rooted in imperial pursuits and defense. Why might colonizers appropriate designs and symbols from the peoples they colonized? How do the colonizers benefit? What are the costs to the colonized?

- Cultural appropriation continues today. Identify some examples of contemporary cultural appropriation. Who is involved? Who benefits and who suffers in these examples?

- Where do we draw the line for who can and cannot use other cultures?

- What role does power have in appropriation?

Activity

Cultural Appropriation Today: Discuss and Debate

How can we navigate, define, and push back on cultural appropriation and discuss complicated issues in a respectful manner?

Large Group Discussion:

- Why do people misunderstand and misuse ideas and objects from other cultures?

- What are some consequences of cultural appropriation?

- Who benefits from cultural appropriation and who is hurt?

In small groups, select one image set (see links below), and respond to the following prompts:

- Is this cultural appropriation? Why?

- Who is appropriating which culture? How are they benefitting from it?

- Whose culture has power in this situation?

- How can people from dominant cultures be inspired by other cultures without disrespectfully appropriating them?

After discussing these questions, each group presents arguments and opinions to the class using evidence based on the written and visual information in the image sets below. Make time for rebuttals and questions.

#1 Set of Images

- Image #1: Dia de los Muertos Halloween Costume

- Image #2: People in Merida, Yucatán representing souls before Dia de los Muertos

- Supporting Texts:

#2 Set of Images

- Image#1: Beyoncé in Indian Attire in Coldplay Music Video

- Image #2: Women in Traditional Indian Attire

- Supporting Texts:

Additional Resources

Grades 9-12: Identity and Complexity

Cultural Appropriation in Majolica

T. C. Brown-Westhead

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

21 1/2 × 16 1/4 × 11 3/4 in (54.6 × 41.3 × 29.9 cm)

Unmarked

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

T. C. Brown-Westhead

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

21 1/2 × 16 1/4 × 11 3/4 in (54.6 × 41.3 × 29.9 cm)

Unmarked

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Majolica ware takes myriad forms, from cats and monkeys to bamboo and beehives. While some imagery was familiar to nineteenth-century consumers, producers sometimes drew on motifs from colonized cultures for their wares. Cultural appropriation occurs when someone takes intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. [note]Adapted from From, Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law, by Susan Scafidi, 2005.[/note] By appropriating symbols, figures, and forms from foreign civilizations and placing them in new contexts, some majolica normalized and perpetuated misinformed stereotypes of cultures outside of western Europe for British and American consumers. However, not all intercultural borrowing is disrespectful and damaging. This lesson considers the effects of cultural appropriation and offers students the opportunity to reflect on their own complex identities through a reflective artwork.

Essential Question

How can we responsibly borrow imagery from another culture?

See Deeply

- Look closely at this ceramic garden stool. What do you notice? Pay careful attention to the details that indicate the culture it references. List the details you and your classmates find.

- At the time this stool was made, idealized images of ancient Egypt had been part of the British imagination for nearly a century and had become especially popular due to recent British imperialism in the Middle East. As a result, ancient Egyptian imagery was often appropriated for British companies’ profit, without regard for its original meaning. Compare the garden stool’s symbols and figure to images of original ancient Egyptian artwork linked below. What similarities and differences can you identify?

View Slide Show

Think Critically

- This garden stool might have been used in a greenhouse in which a middle-class British family could enjoy plants imported from warmer, foreign climates. Imagine it in one such Victorian greenhouse. What is its purpose in this context? How does it relate to its environment?

- Now look at the seated sculptures of the Pharaoh Ramses II at the Great Temple at Abu Simbel, Egypt. How do the Egyptian temple statues interact with the temple? How does their purpose compare with that of the majolica garden stool?

- How does removing the Egyptian imagery from its original environment, in the form of this garden stool, change its meaning, power, or value?

- Does this stool give you an accurate understanding of Egyptian life – in the nineteenth century or today? What information would help you learn about contemporary Egyptian culture?

Build Freely

While cultural appropriation continues today, many contemporary artists also use it to complicate a narrative that might essentialize or stereotype their culture. Look carefully at Revolucionarios y Guadalupanos, a collage by Mexican artist Ernesto Muñiz.

- Which cultural references does Muñiz include?

- Who is in control of the story this artwork tells? Why is that important?

- How is this work different from the majolica garden stool?

- What does appropriation accomplish in this context?

T. C. Brown-Westhead

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

21 1/2 × 16 1/4 × 11 3/4 in (54.6 × 41.3 × 29.9 cm)

Unmarked

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

T. C. Brown-Westhead

ca. 1880

Earthenware with majolica glazes

21 1/2 × 16 1/4 × 11 3/4 in (54.6 × 41.3 × 29.9 cm)

Unmarked

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Activity

Collaging Your Identity

For centuries, artists and artisans have been inspired by and incorporated motifs from other cultures to respond to changing circumstances. Appropriating cultural motifs can be a tool of resilience, an instrument for criticism, and an expression of complex identities. In our globalized world, where media and the internet provide content so readily, students will repeatedly encounter the choice of if and how to engage with other cultures in their own creative and academic work. This activity offers a framework with which they can make conscientious decisions about engaging with other cultures in their work.

Materials

- Printed images

- Scissors

- Paper

- Glue

- Colored pencils

Watch this short video on distinguishing between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation.

What images and traditions make you, you? Browse the selection of images and motifs below, which are meaningful in their own cultures. Do any reflect your identity? Search here and on the internet for motifs that you identify with and design a collage that shares an aspect of your identity (for instance, your cultural heritage, your dreams and aspirations for the future, a historical event you find inspiring, etc.). You can choose to borrow motifs from another culture if you consider them relevant to the expression of your identity.

If you decide to borrow motifs from another culture, consider these two questions:

- Do you understand the cultural significance of this motif, and its role and importance in its original context? If you don’t, spend some time learning about it. Write down three facts you learned about its use and meaning in its own culture. Remember, when a motif is sacred, or has a spiritual meaning, it’s especially important that you understand its significance.

- What is your motivation to use it? Identify it in a sentence or two and be prepared to share. Remember, if the only reason you are interested in a motif is because it’s different from your own culture, go back to your research and re-think whether it really connects with your identity.

Share your process and final result with your class. Explain the motifs from your own background that you included, and also credit any motifs you borrowed from other cultures. If you had intended to incorporate a motif but in the end decided not to, explain why.

Examples of Meaningful Cultural Motifs

Mexican effigies of La Calavera Catrina

Japanese Ukiyo-e wood engravings

Broadway, New York

Venice festival masks

Egyptian faience

Polynesian Tapa Cloth

Germantown revival Navajo weaving

Mosaics of Islamic Mosques

Resource for Teaching about Cultural Appropriation

Anti-Racist Art Teachers – Cultural Appropriation

Grades 9-12: Majolica & Kitsch

Imitation, Excess, and Irony

Kitsch is an adjective that describes art and design objects that are considered to be in poor taste because they exhibit an excessive melodrama or sentimentality. Sometimes we can appreciate kitsch objects in an ironic or knowing way. Kitsch objects also tend to appeal to a wide audience. This lesson re-examines the aesthetic qualities of majolica ceramics, which were particularly popular for Great Britain’s expanding middle class in the nineteenth century, and invites students to consider ideas of taste and excess.

Paul Comoléra (1818–1897), designer;

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1875; this example 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

59 ⅞ × 27 ½ × 17 ¼ in (152 × 70 × 43.8 cm)

Molded on base: P. COMOLÉRA; impressed marks: MINTON // 2045 // cipher for 1876 // other ciphers

The English Collection

Griffen, Smith & Co.

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

7 ⅜ × 9 × 5 ½ in (18.7 × 22.9 × 14 cm)

Molded mark: GSH monogram

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Paul Comoléra (1818–1897), designer;

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1875; this example 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

59 ⅞ × 27 ½ × 17 ¼ in (152 × 70 × 43.8 cm)

Molded on base: P. COMOLÉRA; impressed marks: MINTON // 2045 // cipher for 1876 // other ciphers

The English Collection

Griffen, Smith & Co.

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

7 ⅜ × 9 × 5 ½ in (18.7 × 22.9 × 14 cm)

Molded mark: GSH monogram

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Essential Question

How might form, color, and material express an attitude?

See Deeply

- What textures do you notice in the peacock sculpture? What textures do you notice in the corn teapot? Imagine you are able to touch these objects. What do they feel like? Do they share any textures?

- Look closely at the peacock; how might you describe the animal’s pose? What words would you use? Try standing like the peacock. How does it feel? What else do you notice about the attitude of this stance?

- Look closely at the corn teapot. Which elements look natural? What looks unnatural?

Think Critically

- What aspects (form, color, texture) of the peacock and corn teapot are appealing to you? Why are they appealing? What aspects are not appealing to you? Why?

- Imagine living with one of these objects. Where would you place it in your home? How would you use it or interact with it? What would owning one of these objects say about you or your mindset?

- Based on the explanation in the introduction to this lesson, what elements of kitsch are present in these objects?

Build Freely

- Are the peacock and the corn teapot representative of good taste or bad taste? What do you see that makes you say that? How do you know what good or bad taste is?

- Do these objects seem to know that they are good taste or bad taste? What do you see that makes you say that?

- Is an excessive aesthetic a bad thing? Why or why not?

- Do you own or like a kitschy object? What do you like about it? What do you think it says about your identity?

Activity

Excessive Containers

How might an object show excess? What does excess look like? A kitsch aesthetic can express many things including sincerity, irony, and enthusiasm. Using the peacock and corn teapot as points of reference, design an excessive container (a cup, bowl, teapot, pitcher, etc.) that you would want to live with.

Materials

- Model Magic or play dough (here’s a homemade recipe) for 3-D models

- Bristol board or cardboard for 2-D models

- Fabric

- Thread or yarn

- Markers

- Construction paper

- Scissors

Reflection

In a written paragraph or class conversation answer the following questions:

- Looking at the object you have created as a whole, which aspects of your design might appeal to a wider audience?

- Does your object qualify as kitschy? Why or why not?

Object Chat: A Creative Writing Exercise

Twentieth-century examples of kitsch in art include Jeff Koons’s 1988 sculpture of Michael Jackson and Bubbles or Cassius Marcellus Coolidge’s 1903 painting, A Friend in Need. Both art objects are recognized for their bad taste, as well as the mass appeal of their subject matter. Imagine one of these objects is in conversation with the majolica corn teapot or the peacock. What attitudes might they try to express to each other? Is their style of kitsch similar or different? Support your interpretations with material details such as form, color, and texture.

Additional Resources

Grades 11-12 (AP): The World in Your Living Room

Globalization, Exploitation, and Fantasy

Majolica provided opportunities for British and American middle-class consumers to beautify their homes and engage in visual fantasies. The three objects in this lesson evoke cultures and places that were foreign to the British and American consumer, and exoticised through their forms and iconography. Owning such objects expressed their owners’ awareness or knowledge of the wider world. However, these objects also reflect the uneven and often tense relationships between one culture and another. In our globalized contemporary society, many of our personal items also connect us to networks of trade, exploitation, and cultural interactions. We can, therefore, use majolica to think about the ways in which many of the issues involving globalization and consumerism today have long existed.

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company

Shape designed ca. 1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes

9 1/4 × 6 5/8 × 6 in (23.4 × 16.8 × 15 cm)

Impressed mark: 51 surrounded by four linked W’s within a circle surmounted by a crown [Royal Worcester maker’s mark]

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1867–68; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

9 7/8 × 4 1/2 in (25 × 11.5 cm)

Impressed marks: MINTONS // 1379 // 3 // cipher for 1873

Rena and Sheldon Rice

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company

Shape designed ca. 1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes

9 1/4 × 6 5/8 × 6 in (23.4 × 16.8 × 15 cm)

Impressed mark: 51 surrounded by four linked W’s within a circle surmounted by a crown [Royal Worcester maker’s mark]

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1867–68; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

9 7/8 × 4 1/2 in (25 × 11.5 cm)

Impressed marks: MINTONS // 1379 // 3 // cipher for 1873

Rena and Sheldon Rice

George Jones & Sons

Design registered 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

8 × 12 ⅜ × 3 ⅝ in (20.4 × 31.4 × 9.2 cm)

Molded mark: British registry diamond for March 30, 1876, parcel 4; painted mark: 3520 / 30

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

George Jones & Sons

Design registered 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

8 × 12 ⅜ × 3 ⅝ in (20.4 × 31.4 × 9.2 cm)

Molded mark: British registry diamond for March 30, 1876, parcel 4; painted mark: 3520 / 30

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Essential Question

How do the objects we use to enrich and beautify our lives reflect our relation to an interconnected world?

See Deeply

- Look closely at each object. What motifs and narratives can you identify?

- Which one of these objects do you think has the most visual impact? Why?

- Each of these objects can potentially hold something. What would you place in each one?

- What kinds of interiors do you imagine these objects in? What do they look, smell, and sound like? Where are they? Who inhabits them?

Think Critically

Each of these objects reference some sort of object that would have been considered “exotic” to a nineteenth-century British consumer. The teapot is in the shape of a Chinese junk sailing ship loaded with crates that may hold tea, porcelain, or other goods. The yellow vase imitates a particular kind of monochrome porcelain produced for the Chinese emperor that began to appear in European collections following the looting and destruction of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing during the Second Opium War (1856-1860).[note]Stacey Pierson, “‘True Beauty of Form and Chaste Embellishment’: Summer Palace Loot and Chinese Porcelain Collecting in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” in Collecting and Displaying China’s Summer Palace in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France, ed. Louise Tythacott (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 72-86.[/note] Indicative of the loose understanding of Asian cultures at this time, the vase was part of a line of objects marketed with “Persian” glazes, referencing the intense appealing colors of Middle Eastern wares. The vase reproduces a nautilus shell, a good imported to Europe from the Indian Ocean since the Renaissance and used to fashion many marvelous princely vessels. It also suggests the blossoming trade for exotic flora and fauna and new fashions in Europe for greenhouses, terraria, and aquaria to keep them in.

- In what way do these objects highlight or obscure intercultural relationships?

- What do these objects say about:

-

- the exploitation of people and things?

- interest in other cultures?

- economic connections?

- To what extent do you think these are objects for display or private use? How would this use affect their meaning?

- What image of oneself do you think the owners of these objects could create with them? How could the owners use them to make a personalized space?

Build Freely

- What is the connection between the owner of these objects and the global relationships that they represent? How might possessing one of these objects implicate the owner in these relationships?

- Which of your possessions reminds you of a place that is far away from where you normally live? What about the object stimulates that connection? Do you think its appeal relates to how you perceive or engage with that place or the culture there? In what ways?

- Think about a lifestyle that you find aspirational or desirable. How much does this lifestyle feature objects from around the world?

Activity

Objects’ Journeys: A Creative Writing Exercise

This creative writing exercise invites students to see objects as part of larger systems of moving things and people. It draws on the haptic learning lesson created by poet and educator Ama Codjoe and should take about 35–40 minutes.

Writing Prompt:

Write a personalized narrative from an object’s perspective of its travel from Asia to Europe.

Step One:

Choose one of the objects referenced by these ceramics: a Qing-era vase, a Chinese junk, or a nautilus shell. Look carefully at images of your chosen object. Imagine it as clearly as possible visually, but also imagine touching or holding it, smelling it, and perhaps hearing it.

Step Two:

For five minutes, using your observations from the previous step, write a faux product description on a shopping website for the object. How does the seller present it?

Step Three:

Now write a description of the object as if the object itself were speaking to the potential buyer. What would the object say differently from its seller? What knowledge might the object have that the seller could not know?

Step Four:

Imagine you are the object traveling from Asia to Britain or the US. Write one or two diary entries describing moments in its journey.

Questions to Consider

- Would it be better to choose moments at the beginning, middle, or end of the voyage?

- Does the object experience this journey with fear, excitement, anxiety, or wonder?

- Does it take this journey willingly?

- What is its opinion of the places and people it encounters?

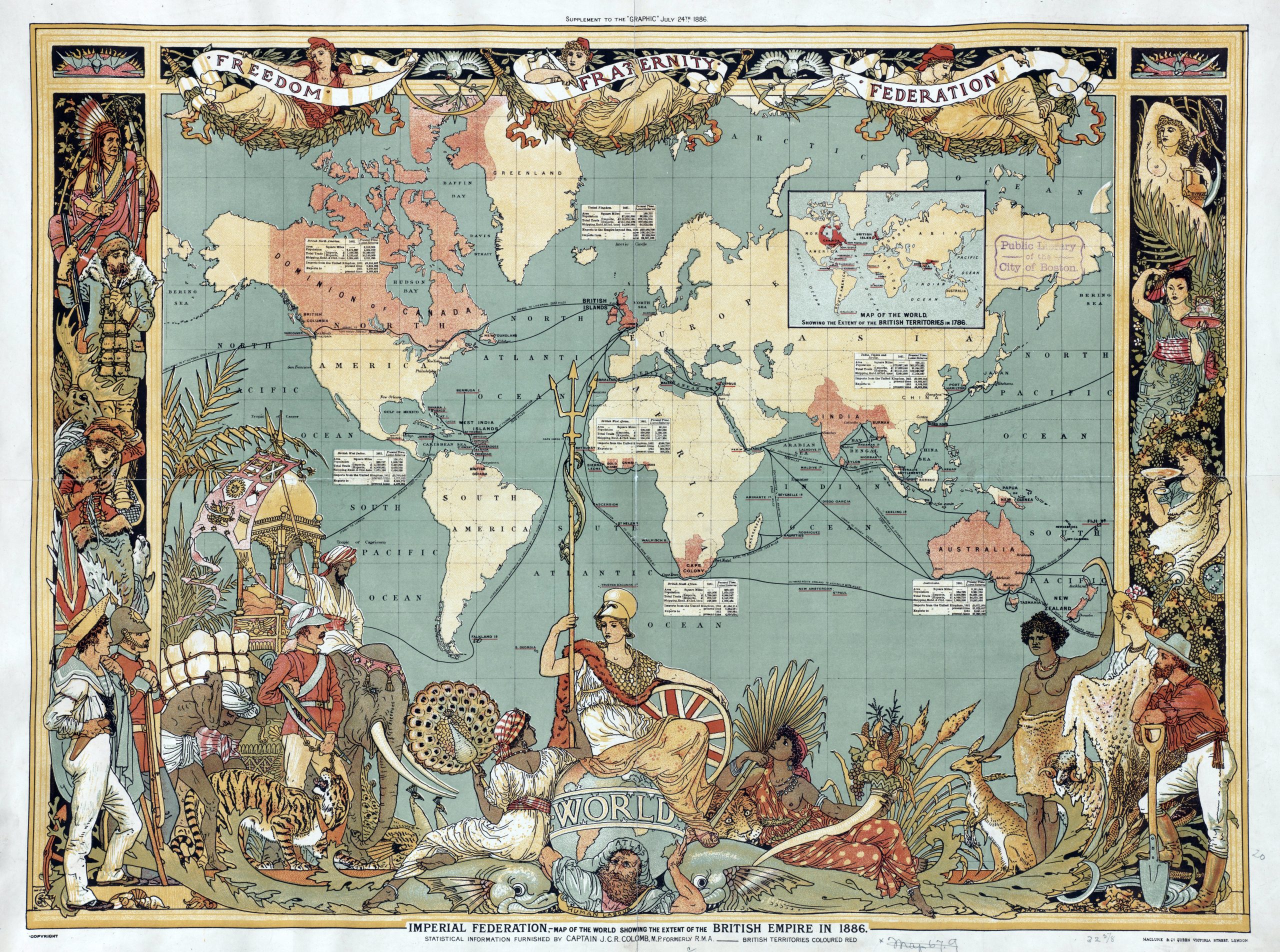

Use the image below of a world map with nineteenth-century trade routes to better imagine what distances these objects are traveling.

Step Five:

Share or describe your story. Discuss similarities and differences in your classmates’ perspectives.

‘Imperial Federation, Map of the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886,’ By Walter Crane (1845-1915).