British ascendancy was unchallenged in the second half of the nineteenth century. Imperial expansion had funneled the massive wealth of Britain’s colonies back to the United Kingdom, and enabled unprecedented access to raw materials and new markets worldwide. Meanwhile, increased domestic factory production, fueled by coal and steam, transformed the nation into the world’s leading industrial power. Consumer goods of all varieties were in great demand both at home and abroad, and British manufacturers were eager to supply them.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a focus on innovation and design became vital to remaining competitive in what was an increasingly global marketplace. At the leading English firm of Minton & Co., French-born-and-trained art director Léon Arnoux (1816–1902) developed a type of glazed earthenware that, from its launch at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, emerged as a particularly versatile medium. Majolica could be made to resemble the Renaissance ceramics increasingly admired for their polychrome decoration and sculpted surfaces—Italian maiolica and French Palissy ware.

In short order, majolica was also being realized in the many eclectic historicist styles of the Victorian period including the Neoclassical and the Gothic revival. From the 1860s through the 1880s, it frequently drew upon motifs and forms that originated in Asia, especially China and Japan, as well as in ancient Egypt. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, majolica designers also took direct inspiration from science and the natural world, in particular horticulture and zoology, which were subjects of great interest to Victorian consumers. These diverse sources are explored below.

Renaissance Revival

From the 1830s through the 1860s, renewed interest in and admiration for the artistry of the Renaissance blossomed across Europe. Ceramic manufacturers contributed extensively to this revival, often creating designs and decoration that either copied or were otherwise inspired by Renaissance prototypes. In England, Minton & Co. became a leading proponent, and the firm’s newest product, majolica, lent itself well to Renaissance-inspired designs. Indeed, the names under which Minton first marketed its new ware—“majolica,” “Palissy,” and “Della Robbia”—directly evoke historical ceramics. Minton was celebrated in the 1850s and 1860s for its revivalist wares, much of which were held up by critics and authorities in the world of art and design as exemplary of some of the best new manufactures. Renaissance revival designs became less prominent by the late 1860s, but they continued to be made by many majolica manufacturers through the 1880s.

View Slideshow

Alfred George Stevens (1817–1875), decoration designer; attributed to Thomas Kirkby (1824–1890), painter

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1855, decoration designed ca. 1862; this example 1864

Earthenware with majolica glazes painted with enamels

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 184-1864

The form of the Minton vase on the left is derived fairly directly from documented sixteenth-century Italian maiolica examples such as the vase executed by the Patanazzi family workshop also shown in this slideshow. The majolica glazing and detailed overglaze enamel embellishment of the Minton vase, however, cannot be so precisely linked to a historical prototype; instead, this surface ornamentation represents a sophisticated synthesis of motifs by its designer, Alfred Stevens, who had gained extensive knowledge of Renaissance art while studying in Italy. Minton showed ceramics with decoration designed by Stevens to acclaim at the London International Exhibition of 1862, and the South Kensington Museum (today’s Victoria and Albert Museum) acquired this example in 1864 as a specimen of superior modern manufacture.

Left

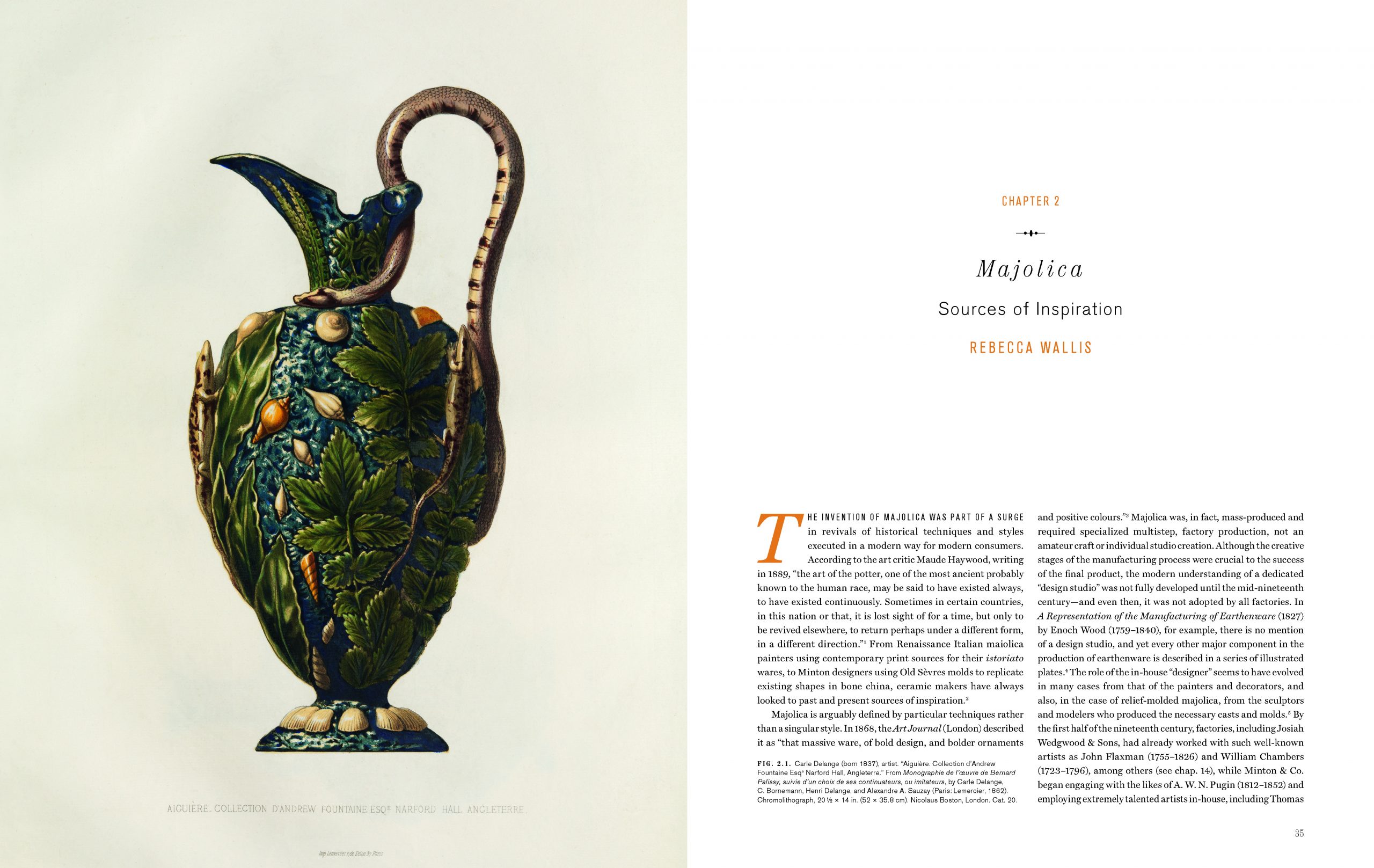

From Monographie de l’oeuvre de Bernard Palissy, suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs, ou imitateurs

Alexandre Sauzay (1804–1870) and Henri Delange (born 1804), authors; Carle Delange (born 1837) and C. Bornemann, artists

Paris: Lemercier, 1862

Book

Nicolaus Boston, London

Right

George Jones, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1867

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

Left

From Monographie de l’oeuvre de Bernard Palissy, suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs, ou imitateurs

Alexandre Sauzay (1804–1870) and Henri Delange (born 1804), authors; Carle Delange (born 1837) and C. Bornemann, artists

Paris: Lemercier, 1862

Book

Nicolaus Boston, London

Right

George Jones, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1867

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

Prints were an important design source in the Victorian period, just as they had been for potters in preceding centuries. To help educate and inspire their designers, ceramic factories often collected prints or books, as did municipal libraries in pottery-manufacturing towns.

The large-scale colored print, or chromolithograph, on the left is included in a book devoted to the work of Bernard Palissy (1510–1590) and his followers. The designer of the jug on the right clearly studied Palissy’s creations in order to produce this interpretation in majolica, which is a close copy of the original shown in the print. This nineteenth-century jug model manufactured from the late 1860s by the English firm of George Jones is decorated with aquatic plants and pond life: a snake flexes to form the handle of the vessel, while lizards perch among weeds and shells on its sides.

Eclecticism

The eclecticism that characterized nineteenth-century design is defined in part by a series of concurrent historical revival movements in which styles of the past were reinterpreted for contemporary application. In addition to reimagining Renaissance period source material, majolica manufacturers mined the art and design of ancient Greece and Rome as well as of medieval Europe for new forms and decoration. Leading potteries were thus able to offer consumers a wide range of ornamental goods with diverse aesthetic appeal.

Designed 1859; this example 1860

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Click Objects Above to Explore

Designed 1859; this example 1860

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

The rediscovery and revival of the art and design of ancient Greece and Rome strongly influenced the arts of Europe from the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries; and in turn, classicism, as interpreted through the lens of the Renaissance, was a hugely important source of inspiration for designers active during the Victorian period. The style lent itself to grandeur and bold decoration and was thus a mainstay of nineteenth-century design.

This ewer and stand in the manner of classically inspired Renaissance metalwork is decorated with portraits of three leading women of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries: Elizabeth I and Marie de’ Medici, queens of England and France, respectively, and Diane de Poitiers, mistress of Henri II of France. It was made for the Crystal Palace Art Union, a subscription-based society founded in 1859 and dedicated to “the diffusion of a love for the finer productions of art-manufacture, and an elevation of the standard of taste among the general public.” An annual subscription entitled members to select from a group of “art-manufactures,” which often included models made by leading British ceramic producers, such as this Minton & Co. ewer and stand offered in 1860.

Click the image above to see design drawings for the ewer and stand.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes and metal mounts

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

The earthenware and stoneware tankards common throughout Northern Europe in the Middle Ages and Renaissance also inspired majolica designers. Traditionally a utilitarian object for domestic or tavern use, the form takes on a more whimsical character in majolica, often featuring decorative scenes of figures picking grapes, harvesting, hunting, or reveling as in this model. By the Victorian period, tankards from past centuries were highly collectable and had themselves become display pieces.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes and metal mounts

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

The earthenware and stoneware tankards common throughout Northern Europe in the Middle Ages and Renaissance also inspired majolica designers. Traditionally a utilitarian object for domestic or tavern use, the form takes on a more whimsical character in majolica, often featuring decorative scenes of figures picking grapes, harvesting, hunting, or reveling as in this model. By the Victorian period, tankards from past centuries were highly collectable and had themselves become display pieces.

Natural Motifs

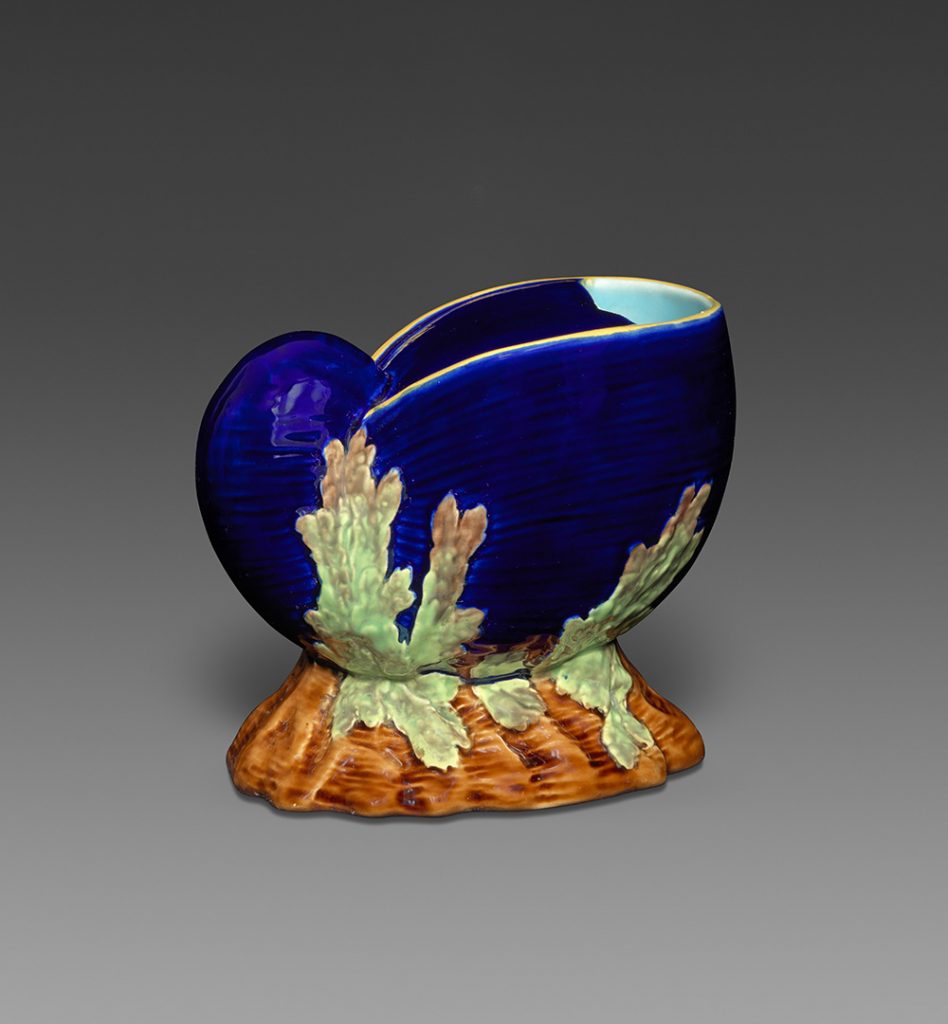

Shells

The nineteenth century was a time of burgeoning interest in the natural world. Scientists and amateur enthusiasts sought to document the earth’s plant and animal species, a practice that ultimately led to an abundance of books, printed indexes, catalogues, and papers supporting their discoveries. A popular subcategory of this pursuit was conchology, or the study and collection of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial shells.

Shell collecting reached its peak in England during the 1850s and 1860s, and was greatly enhanced by Britain’s expanding empire and trade in the Pacific. Exotic shells were imported as curiosities and valued collectibles—shell auctions were a common occurrence, with rare and perfect specimens fetching particularly high prices. Capitalizing on this interest, majolica manufacturers designed a wide range of wares incorporating shells in a seemingly endless variety of shapes and sizes.

Click Objects Above to Explore

Plate 3 from Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands and Parts of South America Visited during the Voyage of the H.M.S. “Beagle”

3rd edition

Charles Darwin

New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1897

Book

Private collection

English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) first published this book in 1844 as the second of three important geological works resulting from the five-year voyage of the HMS Beagle. In addition to geology, Darwin had knowledge of marine invertebrates and was charged with collecting specimens, fossils, and other natural history samples. He kept meticulous notes of his observations and theoretical speculations, which he would later develop into his theory of natural selection. Several plates from Darwin’s publication document that the interest in shells extended to the most important scientists of the nineteenth century.

Click on the shells in the image above to see examples of majolica in the exhibition that feature shell motifs.

Animals

From the menageries of ancient Rome to the royal zoos of the eighteenth-century courts, animals—both exotic and native species—have long been a source of fascination in Europe. The vast expansion of international travel and trade during the Victorian era coincided with a widespread interest among European and American scientists and amateur enthusiasts in the documentation and classification of the earth’s fauna. Opportunities for zoological inspiration grew markedly during the nineteenth century, reaching a much broader public. The Zoological Society of London, established in 1826, built the first animal houses in the capital city’s Regent’s Park and opened its gardens to members in 1828. There, exotic animals, including elephants, lions, and zebras, were displayed to an eager audience, who viewed them as both educational and entertaining. For those unable to venture into the bigger cities or abroad, the animal kingdom was brought to them by traveling circuses, menageries, exhibitions, and an extensive range of books and other printed matter. Animals have been a subject of European ceramics throughout history, but their popularity reached a high point in the second half of the nineteenth century in majolica.

Thomas Forester, Longton, Staffordshire

ca. 1882

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Aviva and Gerald Leberfeld

The Jumbo teapot was highlighted in the trade press in 1882 and may have reflected Thomas Forester’s effort to appeal to consumers on both sides of the Atlantic. A large elephant named Jumbo was a beloved attraction at the London Zoological Society from 1865 until 1882, when he was sold to American circus showman P. T. Barnum (1810–1891), who for the next several years, featured the animal in what was billed “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

Thomas Forester, Longton, Staffordshire

ca. 1882

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Aviva and Gerald Leberfeld

The Jumbo teapot was highlighted in the trade press in 1882 and may have reflected Thomas Forester’s effort to appeal to consumers on both sides of the Atlantic. A large elephant named Jumbo was a beloved attraction at the London Zoological Society from 1865 until 1882, when he was sold to American circus showman P. T. Barnum (1810–1891), who for the next several years, featured the animal in what was billed “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

The Influence of China and Japan

Foreign cultures have long held allure for artists and designers, and in Europe, Chinese and Japanese art in particular has exerted a strong influence, resulting in countless examples of interpretations ranging from direct copies to fantastical re-imaginings. During the nineteenth century, museums and exhibitions provided the public with greater opportunities to see a variety objects from Asia, especially China and Japan.

China had a long history of trade with Europe, and Chinese objects, notably ceramics, became sought after, and had significant influence on European ceramic production from the seventeenth century onward. British museums voraciously collected Chinese art and artifacts, while Britain’s interventions in China, including the two Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860), cultivated further English awareness of the country and its arts. Chinese sources inspired majolica designers from the early 1850s onward.

Japan’s more than two-hundred-year isolation from trade and cultural exchange had ended by the late 1850s, after the forceful intervention by American and European powers. It was not until the London International Exhibition of 1862, however, that Japanese objects were seen in large quantities by a wide audience. The display was popular with the public and enormously influential on British designers. Critics advocating for design reform in Britain urged manufacturers and designers to look to Japanese objects to improve their own work. The Japanese government organized important displays at subsequent world’s fairs in the 1860s and 1870s, and these, along with a large increase in trade, resulted in wide awareness of Japanese art, which inspired art and design in both Europe and America. Japanesque designs began to be seen in majolica by the late 1860s, and were common by the 1880s.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1867–68; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice

Minton art director Léon Arnoux (1816–1902) developed a range of rich, saturated glaze colors in the early 1870s. The firm dubbed them “Persian,” and indeed, they may have been inspired by colors associated with Middle Eastern ceramics. Equally, another source may have been the monochrome glazes used on Chinese ceramics, which became fashionable in Europe after the Second Opium War (1856–1860) and the sacking of the Summer Palace (1860), when many ceramics from the Chinese imperial collection were brought to Europe. Minton initially applied these vibrant new glazes, usually singly or two at a time, to shapes that were modeled after Chinese prototypes, as seen here.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1867–68; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice

Minton art director Léon Arnoux (1816–1902) developed a range of rich, saturated glaze colors in the early 1870s. The firm dubbed them “Persian,” and indeed, they may have been inspired by colors associated with Middle Eastern ceramics. Equally, another source may have been the monochrome glazes used on Chinese ceramics, which became fashionable in Europe after the Second Opium War (1856–1860) and the sacking of the Summer Palace (1860), when many ceramics from the Chinese imperial collection were brought to Europe. Minton initially applied these vibrant new glazes, usually singly or two at a time, to shapes that were modeled after Chinese prototypes, as seen here.

Johann Hasselmann (John) Hénk (1847–1921), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

ca. 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

John Hénk, an important designer for Minton in the 1870s, likely drew upon Japanese prints to realize the model shown here. Such images were widely circulated in Europe by the 1870s and influential in European art of the late nineteenth century. In this example, Hénk has translated what would have been a flat picture into three dimensions and added additional markers of Japanesque design, including the stylized flowering plum and pine trees that frame the figure group.

Egyptian Revival Style

Following Napoleon’s campaign in the Middle East (1798–1801), which included excavations of ancient Egyptian cultural sites and subsequent publication of the campaign’s findings, Egyptian decorative motifs began to be used by many European and American designers. By the mid-nineteenth century, the development of modern Egyptology, increased trade with Europe, and private travel to the region spurred further awareness and appreciation of Egypt’s rich culture. Interest spread through the fine arts and literature as scholars, writers, and artists attempted to record their experiences of the region’s people, landscape, and architecture. English majolica manufacturers began making Egyptian-inspired designs in about 1870, likely stimulated by European interventions in the Middle East, including the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Victoria and Albert Museum, Wedgwood Collection at World of Wedgwood, Barlaston, UK, acc. no. 9002. Presented by the Art Fund with major support from the Heritage Lottery Fund, private donations, and a public appeal.

This inkstand and well in the form of a Nile barge and canopic jar reflect the Victorian enthusiasm for Egyptian forms and ornament. Though Wedgwood introduced this desk set in black stoneware in the early nineteenth century, the model found new life and commercial appeal when it was reintroduced in majolica in the mid-1870s.

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Victoria and Albert Museum, Wedgwood Collection at World of Wedgwood, Barlaston, UK, acc. no. 9002. Presented by the Art Fund with major support from the Heritage Lottery Fund, private donations, and a public appeal.

This inkstand and well in the form of a Nile barge and canopic jar reflect the Victorian enthusiasm for Egyptian forms and ornament. Though Wedgwood introduced this desk set in black stoneware in the early nineteenth century, the model found new life and commercial appeal when it was reintroduced in majolica in the mid-1870s.