During the nineteenth century, the British pottery industry was largely concentrated in the central English county of Staffordshire, in the six towns and numerous villages that make up the modern city of Stoke-on-Trent, often simply called the “Six Towns” or “The Potteries.” This region possessed an abundance of the basic raw materials necessary for ceramic production—deposits of clay, to form the wares, and coal, to fire the kilns. No other part of England had a manufacturing district so utterly associated with one trade. This section features wares made by English firms, from the large, well-established concerns that produced a wide range of ceramics—including porcelain, parian, stoneware, and a variety of earthenwares—and that added majolica to their production lines from the 1850s through the 1870s, to the smaller ones founded in the second half of 1860s, the 1870s, and the the early 1880s that specialized in majolica manufacture.

These British manufacturers competed for expanding markets both at home and abroad, using a variety of tactics to promote and sell their wares. Many participated in the international exhibitions that punctuated the second half of the nineteenth century. Still more engaged with specialized retail outlets and large department stores, circulated illustrated catalogues of their wares, and purchased print advertisements in trade journals and newspapers. Moreover, many also invested in design, hiring both well-known sculptors and anonymous modelers to create novel products. For protection against piracy in Britain, many firms submitted their new models or patterns to the British Designs Registry, which was in itself a mark of distinction and therefore useful as a promotional tool.

Minton: Britain’s Preeminent Manufacturer

Minton & Co. (after 1883, Mintons Ltd.) was the largest and most important British ceramic manufacturer of the nineteenth century, even rivaling state-supported European factories such as Sèvres in France. Founded in 1793 in the Staffordshire town of Stoke-upon-Trent, the firm flourished under the leadership of Herbert Minton (1793–1858) and his nephew Colin Minton Campbell (1827–1885) who, with French-born art director Léon Arnoux (1816–1902), oversaw the company’s aesthetic and commercial dominance from the 1840s through the 1880s. A large part of Minton’s success was due to its commitment to innovation, including the pivotal development by Arnoux of majolica. The firm debuted this new ware at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, and it would remain among the company’s principal product lines for the next fifty years. An emphasis on the importance of good design was another key factor in Minton’s success. The firm not only employed many well-known European artists and designers, it also supported design education on both national and local levels, and subsidized the education of many of its own employees.

Minton’s clientele was international, ranging from a vast swath of the middle classes to the most elite, including the British royal family. To attract this broad range of consumers, the company invested in mutually beneficial relationships with leading retailers, among them Thomas Goode & Co. in London and Tiffany & Co. in New York. Minton also made a strong commitment to marketing its wares worldwide, most significantly through its prominent displays in the international exhibitions held across the globe in the second half of the nineteenth century. These elaborate presentations featured many of the majolica models included in this section.

Left

Figure of Herbert Minton

Hugues Protât (born 1816; active 1835–1890), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

1860

Parian porcelain

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by M. Protât, 7126-1860

Right

Figure of Colin Minton Campbell, after a bronze statue by Sir Thomas Brock (1847–1922), figure shape no. 501

Thomas Longmore (1846–1901), modeler

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed 1887; this example 1889

Parian porcelain

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Figure of Herbert Minton

Hugues Protât (born 1816; active 1835–1890), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

1860

Parian porcelain

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Given by M. Protât, 7126-1860

Figure of Colin Minton Campbell, after a bronze statue by Sir Thomas Brock (1847–1922), figure shape no. 501

Thomas Longmore (1846–1901), modeler

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed 1887; this example 1889

Parian porcelain

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

These figures made of parian, an unglazed porcelain that resembles marble, portray the two men who led Minton & Co. between 1836 and 1885: Herbert Minton (1793–1858) and his nephew Colin Minton Campbell (1827–1885). The firm became enormously successful under their leadership, gaining a worldwide reputation for innovation and artistry. In this likeness commissioned to commemorate his death in 1858, Herbert Minton is depicted holding a dish and leaning on a pedestal, both of which his firm made in majolica—suggesting, only a few years after its introduction, the importance of the ware to his legacy. The representation of Colin Minton Campbell, copied from a full-size bronze statue that stood outside the Minton factory from 1887, also features a majolica prop, this one in the form of an elaborately modeled stand.

Victor Étienne Simyan (1826–1886), designer

Minton & Co., manufacturer, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1867; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

Minton debuted this impressive vase model at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1867 and went on to feature it at several subsequent world’s fairs, including the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, where the firm showed an example with the rich turquoise blue ground seen here. Designed by French-born sculptor Victor Étienne Simyan, this vase takes its name from the Titan god Prometheus, who is represented on its lid. In Greek mythology, Zeus condemned the immortal to eternal torment for stealing the god’s sacred fire and taking it to Earth. As punishment, Prometheus is chained to a rock; every day, his liver is eaten by an eagle, only to regrow in the night, ensuring the torture is repeated.

Victor Étienne Simyan (1826–1886), designer

Minton & Co., manufacturer, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1867; this example 1873

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

Minton debuted this impressive vase model at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1867 and went on to feature it at several subsequent world’s fairs, including the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, where the firm showed an example with the rich turquoise blue ground seen here. Designed by French-born sculptor Victor Étienne Simyan, this vase takes its name from the Titan god Prometheus, who is represented on its lid. In Greek mythology, Zeus condemned the immortal to eternal torment for stealing the god’s sacred fire and taking it to Earth. As punishment, Prometheus is chained to a rock; every day, his liver is eaten by an eagle, only to regrow in the night, ensuring the torture is repeated.

Pierre-Émile Jeannest (1813-1857), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed ca. 1851, this example ca. 1855–60

Earthenware with majolica glazes

H. 24 5/8 x diam. 16 3/8 in. (62.5 x 41.6 cm)

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn Karmason

This model, designed to hold the icy water in which bottles of wine would be chilled, was originally made in porcelain and part of an extensive and acclaimed dessert service that Minton exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The service was purchased by Queen Victoria when she previewed Minton’s display, and the firm named it after her. French designer Pierre-Émile Jeannest was Minton’s chief modeler in the years around 1850, when he also served as a modeling instructor at the Potteries School of Design. The firm began producing this model in majolica about 1855.

Pierre-Émile Jeannest (1813-1857), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed ca. 1851, this example ca. 1855–60

Earthenware with majolica glazes

H. 24 5/8 x diam. 16 3/8 in. (62.5 x 41.6 cm)

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn Karmason

This model, designed to hold the icy water in which bottles of wine would be chilled, was originally made in porcelain and part of an extensive and acclaimed dessert service that Minton exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The service was purchased by Queen Victoria when she previewed Minton’s display, and the firm named it after her. French designer Pierre-Émile Jeannest was Minton’s chief modeler in the years around 1850, when he also served as a modeling instructor at the Potteries School of Design. The firm began producing this model in majolica about 1855.

Henry Hope Crealock (1831–1891)

1873

Pen-and-ink, watercolor, pencil, and retailer’s printed paper label on paper

The Minton Archive, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives,

SD 1705/MS1787

Henry Hope Crealock (1831–1891), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Thomas Goode & Co., London, retailer

Designed 1873; this example 1874

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Minton & Co. would occasionally supply models to one retailer exclusively. Thomas Goode & Co., a leading London purveyor of ceramics, glass, and silver, and Minton’s main retail outlet in the British capital for many years, enjoyed such commercial advantage. This teapot was designed by English artist and author Henry Hope Crealock, who was known for his illustrations of animals and sporting subjects. Crealock served in the British Army for much of his life, spending several years in India, where he likely witnessed this model’s subject—a vulture preying on a snake.

Paul Comoléra (1818–1897), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed ca. 1873–74; this example 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

39 1/2 x 21 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (100.3 x 55.3 x 40 cm)

Joan Stacke Graham Collectio

Born in France, Paul Comoléra studied under Neoclassical sculptor François Rude (1784–1855) and first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1847. Between 1873 and 1876, he worked at Minton & Co., where he was best known for his animal models. His were some of the earliest examples of what would become a popular trend in the second half of the 1870s for animals realized in majolica. Comoléra worked from direct observation of the live subjects he kept in his studio—a methodology that, in combination with his artistic skill, resulted in highly lifelike forms.

Paul Comoléra (1818–1897), designer

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Designed ca. 1873–74; this example 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

39 1/2 x 21 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (100.3 x 55.3 x 40 cm)

Joan Stacke Graham Collectio

Born in France, Paul Comoléra studied under Neoclassical sculptor François Rude (1784–1855) and first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1847. Between 1873 and 1876, he worked at Minton & Co., where he was best known for his animal models. His were some of the earliest examples of what would become a popular trend in the second half of the 1870s for animals realized in majolica. Comoléra worked from direct observation of the live subjects he kept in his studio—a methodology that, in combination with his artistic skill, resulted in highly lifelike forms.

Expansion of British Majolica Manufacture

The growth of industrialization and trade during the nineteenth century in Britain and the United States transformed society, producing not only a new class of wealthy industrialists, bankers, and rail and shipping magnates, but also enlarged and increasingly prosperous middle classes. These consumers sought objects to adorn their homes and tables, and British manufacturers were eager to supply them.

In 1860, the venerable firm of Josiah Wedgwood & Sons began manufacturing majolica, effectively ending the near monopoly on the ware that Minton & Co. had held for almost a decade. Other Staffordshire manufacturers quickly followed suit. Some of these were established potteries with robust existing businesses, while others were more recently founded. Those firms with the means to do so hired in-house and freelance designers to ensure the originality and artistry of their output. Moreover, they submitted their designs to the British government’s Designs Registry, which granted copyright protection in the United Kingdom for a period of three years; they issued printed catalogues or pattern sheets; and they presented their wares in elaborate displays at the international exhibitions held in major cities throughout the world in the second half of the nineteenth century. Commercial success in this highly competitive market was derived from a coordination of design and manufacturing supported by effective promotion and distribution.

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons

Founded in 1759 by ceramic innovator and businessman Josiah Wedgwood I (1730–1795), the Wedgwood company enjoyed great success under his direction and into the early nineteenth century, but the venerable firm was struggling by the 1840s. The leadership of Francis Wedgwood (1800–1888) and his three sons, Godfrey (1833–1905), Clement (1840–1889), and Lawrence (1844–1913), gradually shifted the pottery’s fortunes in the decades that followed. One key advance was the development of a superior line of majolica, which Wedgwood introduced in about 1860 and continued to produce until 1918. During the peak years of its production, from 1865 to 1890, the ware formed a substantial percentage of the firm’s output, and by the 1870s, Wedgwood was manufacturing more majolica than any other kind of ornamental pottery.

Wedgwood engaged leading artists and designers of the day, both as company staff and on a freelance basis, to realize distinctive wares of the highest quality. Its brilliant glazes and the precision of its modeling were celebrated not only at home but also abroad—indeed, the firm enjoyed a substantial export market. Although Wedgwood produced a few grand exhibition pieces in the brightly glazed earthenware, it was first and foremost a pioneer in the manufacture of majolica tableware and other household items, which it sold at prices accessible to the growing middle classes.

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons made significant investments in design during the second half of the nineteenth century, realizing that a commitment to artistry was key to commercial success. Wedgwood, like other leading British firms including Minton & Co. and T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co., benefited from the influx of artists from France who migrated to England in the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1848—among them, prominent sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887), modeler Hugues Protât (born 1816; active 1835–90), and painter Émile-Aubert Lessore (1805–1876). These men contributed to the firm’s aesthetic development, especially in terms of its ornamental majolica.

Hugues Protât (born 1816; active 1835–90), designer

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

Shape designed ca. 1871

Earthenware with majolica glazes, metal, glass, and other materials

Aviva and Gerald Leberfeld

This model, first displayed at the London International Exhibition of 1871, highlights majolica’s malleable, sculptural qualities as well as the Wedgwood company’s ongoing effort to introduce novel shapes into its production. French-born Hugues Protât designed this clock vase along with many other majolica forms for Wedgwood during the 1870s.

By the late 1870s, the taste for brightly colored majolica was beginning to wane. Wedgwood responded in 1878–79 by introducing Argenta, a style of decoration characterized by pale, usually white or ivory grounds, and subdued colors, often in shades of gray and green. Argenta glazed wares were soon selling so well that other potteries in England and the United States adopted a similar palette for their majolica.

The Japanesque design of the cheese stand shown here is consistent with the Aesthetic movement mission to unite the beautiful with the useful through the application of Asian-inspired ornament. Similarly appealing to Aesthetic taste, the fruit tray and spoon employ an exotic peacock motif, a prominent symbol of the influential movement, which reached its height in the 1870s and 1880s. As ornamental as they are functional, the tray and spoon would have been used for berries served as a dessert course or with afternoon tea.

T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co.

In 1861, Thomas Chappell Brown-Westhead (1837–1882) and William Moore (1815–1866) formed a partnership to operate the Cauldon Works. This large porcelain and pottery factory was located in Hanley, one of the six Staffordshire towns comprising the Potteries, England’s principal ceramic-manufacturing district. From about 1865, T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. began producing majolica of excellent quality, which was met with great acclaim at the many international exhibitions in which the firm participated. Although majolica was not the primary focus of its large and diverse production, Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. engaged numerous freelance modelers, sculptors, and other artists to realize original wares, often noteworthy for their inventive design.

Mark Valsler Marshall (1842–1912), designer

T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire, manufacturer

ca. 1877

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

This dynamic rendering of an eagle in pursuit of its prey exudes vigor and intensity—characteristics often associated with the work of British designer Mark Valsler Marshall. Described in the 1871 English census as a sculptor, Marshall was a freelance artist for T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. He notably modeled a pair of life-size majolica tigers for the firm, which it displayed at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1878, as well as other sculptural majolica the company presented in 1889 at the subsequent international exhibition in Paris. Marshall’s models often bear his initials as part of the mold. Such public crediting of designers was relatively new at this time and demonstrates critical acknowledgment by Brown-Westhead, Moore of the artist’s vital role in industry and of the sales potential that such a “signature” might foster in a competitive market.

T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire

ca. 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

The celebrated display of Japanese objects at the London International Exhibition of 1862 and increasing exposure to the decorative and fine arts of Japan in subsequent years offered European artists, designers, and collectors a refreshingly novel and exotic sources of inspiration. Following two centuries of geopolitical isolation, Japanese art and culture was thought to have been spared the ravages of industrialization and was thus considered purer and more aligned with nature than that of developed European nations. This vase model, its shape likely inspired by late Edo period (1603–1868) Japanese bronzes, was one of several majolica designs produced by T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. that reference Asian ornament. It was featured in the firm’s display at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia.

T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire

ca. 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

The celebrated display of Japanese objects at the London International Exhibition of 1862 and increasing exposure to the decorative and fine arts of Japan in subsequent years offered European artists, designers, and collectors a refreshingly novel and exotic sources of inspiration. Following two centuries of geopolitical isolation, Japanese art and culture was thought to have been spared the ravages of industrialization and was thus considered purer and more aligned with nature than that of developed European nations. This vase model, its shape likely inspired by late Edo period (1603–1868) Japanese bronzes, was one of several majolica designs produced by T. C. Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. that reference Asian ornament. It was featured in the firm’s display at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia.

George Jones and George Jones & Sons

George Jones (1823–1893) served a seven-year apprenticeship at Minton & Co. beginning in 1837, and subsequently worked as a traveling salesman for Josiah Wedgwood & Co. and other firms before founding his own highly successful business as a wholesaler of china and earthenware in the early 1850s. The significant capital Jones built up during this time allowed him to embark on pottery manufacture in 1862. His eponymous firm in Stoke-upon-Trent began producing majolica in about 1865–66, and the ware soon became the pottery’s most important product line. Although the identity of the company’s principal designer is unknown, it is likely that George Jones himself or his son Frank Ralph Jones (1846–1911) played a significant role in the development of the firm’s strong aesthetic identity, which was dominated by lifelike relief-modeled animals and plants. The manufacturer enjoyed a strong export business, including to the important American market, and promoted its wares through displays at international exhibitions from the 1860s through the 1880s.

George Jones, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1871–72

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection and Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Intended for use as centerpieces on dining tables, these elaborate modeled comports are allegorical representations of Africa, America, and Europe, each of which is evoked by animals associated with the continent. Such symbolic depictions have a long history in European decorative arts, including ceramics. These particular examples may also have appealed to English pride in the British Empire, which was nearing its height in the second half of the nineteenth century. Material references to empire, from maps and imported plants to ceramics such as these, were common in British homes at this time.

View Slideshow

George Jones, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1871–72

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection and Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

Intended for use as centerpieces on dining tables, these elaborate modeled comports are allegorical representations of Africa, America, and Europe, each of which is evoked by animals associated with the continent. Such symbolic depictions have a long history in European decorative arts, including ceramics. These particular examples may also have appealed to English pride in the British Empire, which was nearing its height in the second half of the nineteenth century. Material references to empire, from maps and imported plants to ceramics such as these, were common in British homes at this time.

John Adams & Co. and Adams & Bromley

John Adams & Co., later Adams & Bromley, was one of the most commercially successful majolica manufacturers in Staffordshire. Beginning in 1864, and for nearly thirty years, it supplied a diverse range of high-quality, reasonably priced majolica tableware, flowerpots, and garden seats to the growing middle-class markets at home and abroad. Most of the company’s original partners, including John Adams (1827/8–1900) and John Bromley (1829–1915), began their careers at Josiah Wedgwood & Sons. This early experience impacted the course of their business, informing the design and decoration of the goods they manufactured. The company participated in several world’s fairs and exported its production widely, including to the vital American market.

John Adams & Co. or Adams & Bromley, Hanley, Staffordshire

ca. 1870s

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

This garden seat model decorated with molded corn and sheaves of wheat tied with ribbon was shown at the London International Exhibition of 1871. The example displayed here features what emerged as the firm’s signature majolica palette: bright green, yellow, brown, and lavender.

Wardle & Co.

Women comprised approximately 40 percent of the workforce in Staffordshire ceramic factories. Most were employed as decorators or “paintresses” or, on the so-called clay end, as attendants or assistants to the male potters. At Wardle & Co., however, there was an exception—the pottery was owned and managed for many years by Eliza Wardle (ca. 1827–1889), the widow of its founder, James Wardle (ca. 1823–1871). Known affectionately as “Mother Wardle,” she oversaw the firm’s growth from a small, struggling business into a successful ceramic manufacturer with a significant export trade. Wardle & Co. made majolica from about 1865, and from the mid-1870s, its production focus was on house- and tablewares, many of original design, finished in fine quality, colorful glazes.

James Wardle or Wardle & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire

Design registered 1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice

The novelty of the disembodied hand was a strangely popular motif used in jewelry, pressed glass, and ceramics of the late nineteenth century. This model of a female hand holding a pineapple may be symbolic of hospitality (the exotic fruit was prized in the nineteenth century) or simply an example of Victorian eccentricity. Majolica vases formed as hands clutching shells, corncobs, and even fish were made by a variety of Staffordshire manufacturers.

James Wardle or Wardle & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire

Design registered 1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice

The novelty of the disembodied hand was a strangely popular motif used in jewelry, pressed glass, and ceramics of the late nineteenth century. This model of a female hand holding a pineapple may be symbolic of hospitality (the exotic fruit was prized in the nineteenth century) or simply an example of Victorian eccentricity. Majolica vases formed as hands clutching shells, corncobs, and even fish were made by a variety of Staffordshire manufacturers.

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company, the only significant English majolica maker not situated in Staffordshire, was founded in 1751 in the city of Worcester in central England’s West Midlands region. The firm made its reputation in the production of high-quality porcelain, but by the middle of the nineteenth century, both its output and standing had declined. Under the leadership of a new owner, William Henry Kerr (1823–1879), and art director, Richard William Binns (1819–1900), the company embarked on a period of innovation in the second half of the nineteenth century. During this time, it introduced a variety of new ceramic bodies including majolica, which it began to manufacture in 1868. The firm was soon receiving critical acclaim and awards at international exhibitions for the sophisticated design of its brightly glazed earthenware, noteworthy for its fine, porcelain-like body.

Worcester Royal Porcelain Company, Worcester, Worcestershire

Designed ca. 1868

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

The general shape of this vase, in the form of a nautilus shell on a coral base, is reminiscent of Renaissance objects that featured in many princely European collections—natural specimens collected for their intrinsic beauty and then mounted in gold. The molded details of the shell, snails, and lizard also recall the lifelike creations of French potter Bernard Palissy (1510–1589). Worcester’s characteristic white porcelain-like body is particularly evident in this piece—in which the shell appears almost translucent.

W. T. Copeland & Sons

A giant of the pottery industry, W. T. Copeland & Sons (before 1868, W. T. Copeland) was comparable to Minton & Co. and Josiah Wedgwood & Sons in the exceptional quality and variety of its wares. Its vast output ranged from parian statuary, elegant hand-painted porcelain made for exhibition, and bone-china dinner sets to the humblest earthenware crockery and stoneware. The successor business to the firm founded in the Staffordshire town of Stoke-upon-Trent by Josiah Spode (1733–1797) in the eighteenth century, Copeland made superb majolica from the late 1860s through the early 1880s. While never its main focus, Copeland’s majolica was realized by a skilled staff and leading freelance designers under the supervision of one of the best artistic departments in the Potteries. The firm featured this ware at several international exhibitions in the 1870s.

Centennial Eagle Pitcher

W. T. Copeland & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

ca. 1876

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Copeland did not participate in the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. However, the importer, wholesaler, and retailer James M. Shaw & Co. of New York opened a temporary store adjacent to the exhibition grounds where it sold special commemorative items supplied by Copeland, including this pitcher with its patriotic imagery. Shaw offered this boldly modeled design in several different ceramic bodies and decorations, including the colorful majolica version shown here.

Joseph Holdcroft

Joseph Holdcroft (ca. 1832–1904) was trained and employed at Minton & Co. before establishing his own, eponymous firm in the early 1860s. His company began majolica production in about 1870 at a pottery factory in Daisy Bank, in the Staffordshire town of Longton. Holdcroft’s business strategy was anchored in manufacturing large quantities of mid-range majolica, supplemented by higher-quality pieces that garnered positive press reviews and upheld the company’s reputation. Although the firm was capable of manufacturing premium majolica in novel shapes, it was considered more of an imitator than an innovator, sometimes copying designs of rival potteries. The company continued to make majolica into the 1890s.

Left

Stamped ink and photograph

National Archives, Kew, BT 43/71/31465

Right

Joseph Holdcroft, Longton, Staffordshire

Design registered 1877

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

From the mid-1870s through the 1880s, Holdcroft manufactured a range of majolica inspired by Japanese art and design. This jug embellished with swimming carp is among the firm’s many Asian-inspired wares glazed in the brilliant, glossy cobalt blue and turquoise that were specialties of the pottery. Holdcroft registered this model with the British government for design protection on September 28, 1877.

William Brownfield & Son(s)

A large manufacturer of stoneware, earthenware, and porcelain based in the Staffordshire town of Burslem, William Brownfield & Son(s) produced majolica of outstanding quality through the 1870s and 1880s. In 1872, the firm hired Louis Jahn (1839–1911) as its first art director. The German-born Jahn, one of several skilled Continental artists who first came to England to work at Minton & Co., was instrumental in directing Brownfield’s product expansion. Like other well-capitalized Staffordshire firms, Brownfield employed celebrated freelance sculptor-modelers such as Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887) and Hugues Protât (born 1816; active 1835–90) to design objects for both general production and exhibition display, shifting the firm’s reputation from moderately priced, useful domestic wares (which were crucial to its success) to what one contemporary reviewer deemed “the highest region of fine art in ceramics.”

Brownfield further distinguished itself by making odd or unattractive, sometimes even disturbing models, tapping into Victorian dark humor and the macabre as a way to differentiate its output from that of the many other Staffordshire manufacturers competing in the same crowded market. The export trade was an important part of Brownfield & Sons’ sales strategy, and to that end, the firm engaged agents and wholesale outlets in large cities throughout Continental Europe, Australia, and the United States. It also advertised extensively in trade journals and newspapers, and built a name for itself in foreign markets through its participation in the international exhibitions of the period.

William Brownfield & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire

ca. 1874–80

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Brownfield’s majolica took inspiration from Renaissance and Asian designs, as well as from Victorian popular culture, including its darker and more grotesque strains. Indeed, the firm manufactured wares intended to provoke and disturb—and, explicitly, to generate commentary in both the popular and trade press. This jug in the shape of a graylag goose whose beak is being forcibly held open by a disproportionately small monkey is characteristic of this genre.

William Brownfield & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire

ca. 1874–80

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Brownfield’s majolica took inspiration from Renaissance and Asian designs, as well as from Victorian popular culture, including its darker and more grotesque strains. Indeed, the firm manufactured wares intended to provoke and disturb—and, explicitly, to generate commentary in both the popular and trade press. This jug in the shape of a graylag goose whose beak is being forcibly held open by a disproportionately small monkey is characteristic of this genre.

Thomas Forester

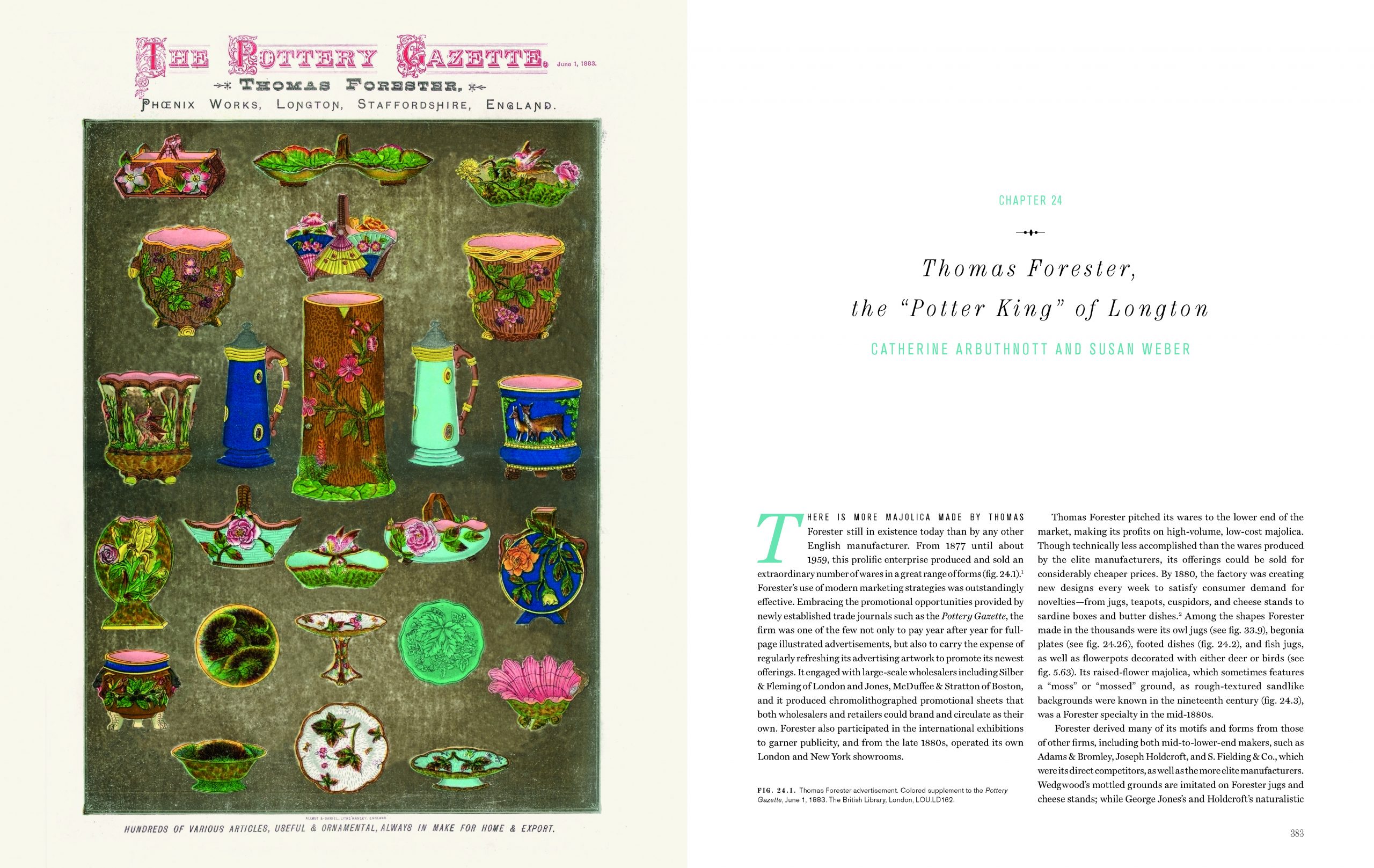

Thomas Forester (1832–1907), proprietor of the eponymous firm (after 1883, Thomas Forester & Sons), catered to the lower end of the market and became extremely successful through his high-volume production of inexpensive majolica. Founded in 1877 in the Staffordshire town of Longton, the company claimed by 1880 that it was introducing new designs every week to satisfy consumer demand for novelties—from jugs, teapots, cuspidors, and vases to cheese stands and flowerpots.

Forester was an astute businessman who embraced modern marketing strategies. Regularly running full page advertisements in trade publications throughout much of his long and successful career, he understood the value of a printed image to create interest in and demand for his firm’s ever-evolving lines of ornamental and useful majolica. Under Forester’s leadership, the firm developed strong relationships with retailers and wholesalers, both domestically and in key markets such as the United States; opened showrooms in London and New York, as well as in many Continental European cities; and featured its majolica as part of extensive displays in world’s fairs during the 1880s and 1890s.

To see examples of Thomas Forester majolica, click on objects depicted in the advertisement below.

Click Objects Above to Explore

Colored supplement to the Pottery Gazette, February 1, 1883. The British Library, London.

Read More

Catherine Arbuthnott and Susan Weber

S. Fielding & Co.

Among the most successful English majolica manufacturers and yet also one of the last firms to begin production of the ware, S. Fielding & Co. made a wide range of goods—from tableware to ornamental pieces for the conservatory and entrance hall. Crisp modeling of naturalistic embellishment, textured backgrounds, and superb coloring distinguish Fielding’s output from that of its competitors. Its namesake was Simon Fielding (1827–1905), one of five partners in the firm’s short-lived predecessor Hackney, Kirkham & Co., which was founded in 1878. Another partner was Frederick Hackney (1848–1892), who would later become manager of Chesapeake Pottery, a Baltimore-based manufacturer. By the end of 1879, Fielding was the sole remaining partner and had renamed the company S. Fielding & Co., although his son Albert (1855–1932), who had trained in the pottery industry as a glaze maker, was almost certainly integral to the firm’s success. S. Fielding & Co. enjoyed a strong domestic and export trade, including to the growing American market.

S. Fielding & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Design registered 1881

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn G. Karmason

S. Fielding & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Design registered 1881

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Marilyn G. Karmason

In the early 1880s, Fielding created a number of designs inspired by Japanese motifs, which enjoyed widespread popularity at the time in both Europe and America. The firm submitted its “Fan” pattern, one of its bestselling designs, to the British Designs Registry for protection against piracy in 1881. This tête-à-tête set, or tea service for two, exhibits some of the bright glazing, including the turquoise blue, that is characteristic of Fielding’s production.

This impressive stand in the form of a hare and duck hanging on a tree stump—seemingly a tribute to hunting and other rural pursuits—was designed to be placed in an entrance hall to hold umbrellas and walking sticks. In 1882, Fielding illustrated this design in an American trade periodical advertisement, promoting itself as “Manufacturers of High Class Majolica, Both Useful and Ornamental” to the lucrative US market.

Samuel Lear

Samuel Lear (ca. 1853–1888) founded his eponymous company in about 1874, developing it from a warehousing business into a successful ceramic factory. Based in the Staffordshire town of Hanley, his firm made majolica from 1881 to 1886, and its most popular designs employ the stylized, naturalistic decoration and motifs characteristic of Aesthetic taste. Rendered in pastel colors against a white or blue stippled background, his palette likewise reflects the Asian influence so integral to the Aesthetic movement. Lear aggressively pursued foreign markets for his wares and advertised frequently in the trade press.

By December 1886, the pottery’s financial difficulties prompted Lear to sell the entire business to Thomas Forester, a leading entrepreneur and majolica manufacturer. Upon receipt of the funds from the sale, Lear secretly fled Staffordshire and defaulted on all of his debts. In a karmic twist of fate, less than two years later, his body was found in a shipwreck off the coast of New Zealand.

In the early 1880s, “barbotine”—originally the French term for a form of slip decorated pottery—was used in England and the United States to refer to ware decorated with high-relief applied flowers and leaves. Lear’s wares in this newly fashionable style were based on pottery featuring applied floral decoration that was first made in Continental Europe and subsequently imported into Britain in large quantities. This type of decorated majolica was in high demand in the 1880s and made by several other Staffordshire manufacturers, including Thomas Forester.

![S. Feilding [sic] & Co. advertisement. From <i>Crockery and Glass Journal</i>, July 1882, page 35. Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, DC. S Feilding [sic] & Co. black-and-white newspaper advertisement with picture of "Hare" umbrella stand on left and "Stork" garden seat on right with text in center.](https://exhibitions.bgc.bard.edu/majolicamania/files/2020/09/MJ-1940-Fielding-advert-6-web.jpg)