Majolica was a common feature of Victorian homes in the second half of the nineteenth century. As the Pottery and Glass Trades’ Journal noted in June 1878:

Judging from our experience we should say that Majolica ware is now the most popular class of domestic pottery. The taste for this class of ware appears to be rapidly on the increase and is spreading itself throughout every branch. Designs to suit majolica are in demand and everything in the way of novelty stands the best chance on the market of ultimate success.

The ware proved popular in both English and American households of the era—for the table and as ornamental accessories to augment the home’s decor—and potteries on both sides of the Atlantic benefited greatly from society’s upward mobility and the growing consumer culture that developed alongside it.

Read More

Gaye Blake-Roberts and Susan Weber

Nature Comes Indoors

In the second half of the nineteenth century, majolica was commonly used for the display of houseplants. In many upper-middle-class residences and, in particular, the homes of the wealthiest, the ware was also employed in the conservatory—a room typically constructed with a glass ceiling and walls in which exotic botanical collections could be maintained and presented. The study and cultivation of plants were popular pursuits for both men and women, and looked upon as edifying. Many Victorians viewed the natural world as a manifestation of divine perfection, and its study, an act of faith.

Majolica vessels such as flowerpots, vases, and wall pockets were designed to frame plants in pleasing ways, and their decoration, like that of majolica garden seats and pedestals or stands, frequently incorporates natural motifs. Often these wares invoke the far-flung corners of the British Empire, where many nineteenth-century ornamental house and conservatory plants originated. At the same time, an underlying tension existed between the desire to have nature close at hand, even in an urban setting, and the fact that majolica was produced by a polluting industry reliant upon coal, lead, and clay. Victorians were aware of the environmental impact of industrialization, and were the first to promote land preservation and movements to curb pollution.

Garden Seats

Sturdy and impervious to water, majolica was considered an ideal material for garden seats, which were used as stools, side tables, or plant stands in both conservatories and outdoors. As the examples shown in the slideshow at right display, this form was produced in a wide range of designs and by a variety of English makers.

View Slideshow

Majolica in the Dining Room

In the nineteenth century, novel and previously unfamiliar foods—including those preserved and processed in new ways or imported as part of increased global trade—became available to large swaths of British and American consumers. Technological innovations such as canning, refrigerated train cars and ships, heated greenhouses, and the industrial manufacture of ice not only broadened access to a wide variety of foods, they also changed the way food was prepared, served, and consumed. Many of the new dishes, silverware, and serving implements introduced during the Victorian period were specifically designed to heighten and celebrate the experience of eating and entertaining—dining tables became places where wealth and sophistication were put on display. Etiquette manuals and domestic advice books helped both hosts and their guests to navigate what were increasingly complex social protocols surrounding food.

At the height of majolica mania, a selection of the colorful wares, interspersed with white earthenware or porcelain, was promoted by tastemakers as the ideal table setting. Notably, majolica, more than any other nineteenth-century ceramic, drew attention to the natural or raw state of a food and to the labor-intensive transformation it had undergone to reach the table in a clean, shelled, cooked, dressed, or otherwise altered state.

George Jones & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Design registered 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

George Jones & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Design registered 1875

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Majolica dessert plates, cake plates, comports, and other serving dishes were extraordinarily popular wares and thus produced by many potteries. The proliferation of designs for strawberry sets, in particular, reflects the overall increase in supply of the fruit in the second half of the nineteenth century as well as improvements in its distribution due to more efficient rail transport across Britain. This model, which features two birds perched on the twig handle of a garden basket, evokes the lush English countryside where strawberries were grown. Removable containers to hold cream and sugar as well as serving spoons complete the ensemble.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

designed ca. 1867, this example 1872

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

A richly laid table embellished with elaborate ceramic centerpieces set a festive tone for a formal dinner-and left a lasting impression on guests. This model was first shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867 and celebrated idyllic rural pursuits in a time of rapid urbanization.

Minton & Co., Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

designed ca. 1867, this example 1872

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower

A richly laid table embellished with elaborate ceramic centerpieces set a festive tone for a formal dinner-and left a lasting impression on guests. This model was first shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867 and celebrated idyllic rural pursuits in a time of rapid urbanization.

Oyster Plates

View Slideshow

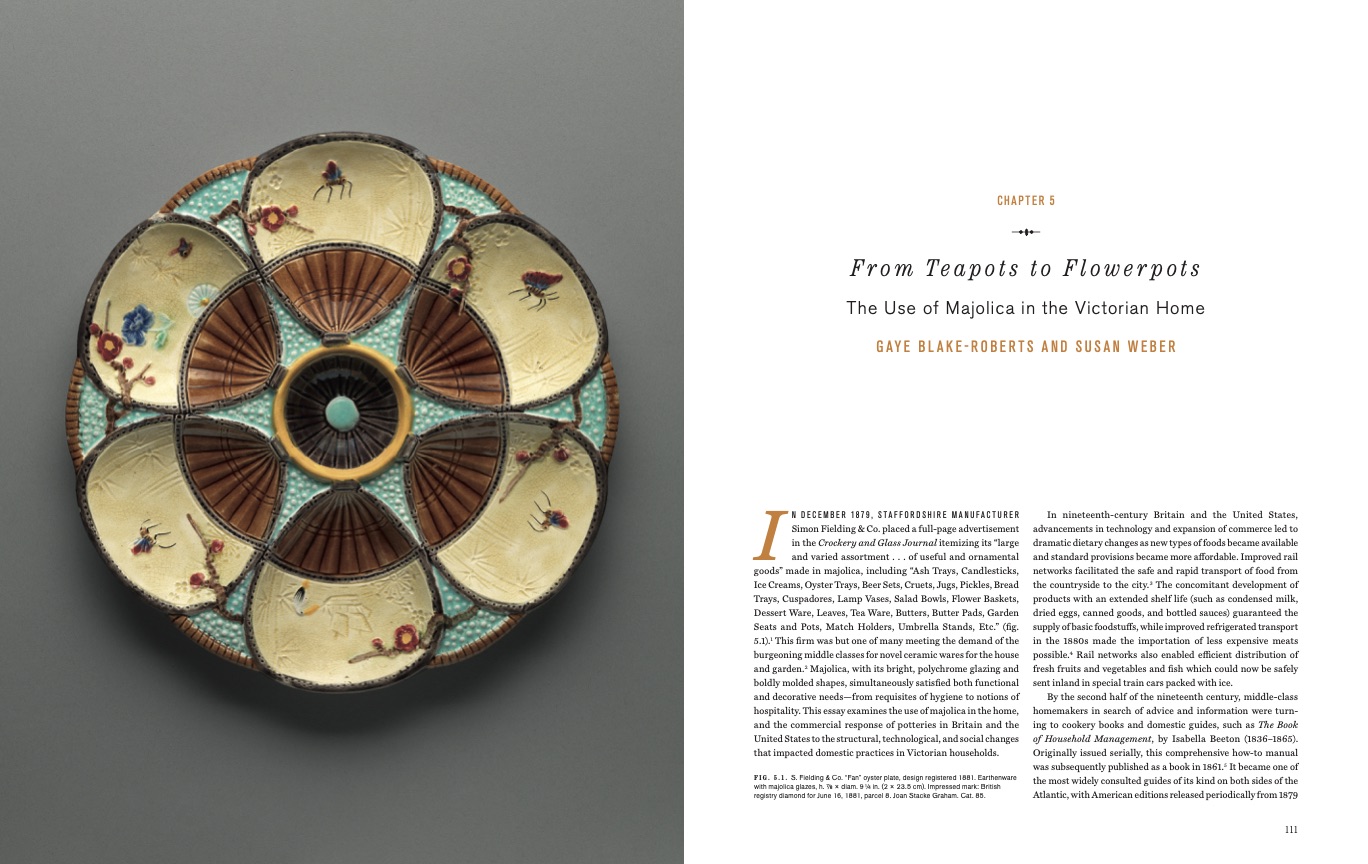

During the nineteenth century, oysters were abundant and inexpensive. They were eaten by rich and poor alike—consumed raw or pickled, baked into stews and savory pies, or prepared in myriad other ways. Formal dinners often began with raw oysters, which might be served on special, vibrantly colored majolica plates or presented on a tiered, rotating stand such as the one featured at the end of this slideshow.

Teawares

Tea was introduced in Britain in the mid-seventeenth century—imported from China by the East India Company. By the Victorian period, the beverage was universally enjoyed for its stimulant effect, and consumed by all classes of society throughout the day. Afternoon and high teas became meals, each with its own etiquette, social rituals, and apparatus. In the United States, afternoon tea was associated with gentility, and a decorative tea set was among the most frequently purchased household luxuries. It is thus perhaps no surprise that teawares were among the objects most frequently made in majolica as can be seen in the adjacent slideshow.

View Slideshow

Tobacco Accessories

In the nineteenth century, after a formal meal, it was customary for women to retire to the drawing room or parlor for tea or coffee, and for men to remain in the dining room to drink port and smoke cigars. Indeed, from the mid-1800s onward, the smoking of pipes, cigars, and cigarettes evolved from a marginally acceptable practice into a widely enjoyed leisure pursuit. Most majolica manufacturers produced accessories for smoking, including tobacco jars, ashtrays, matchboxes, and cigar holders.

View Slideshow

Chewing tobacco was so ubiquitous in the United States that it was a featured American display at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Cuspidors, or spittoons, were genteel receptacles for spit and chewed tobacco. These vessels were fixtures in public spaces such as bars and rail stations as well as in domestic settings, where they were usually placed in dining rooms and parlors. Designs ranged from the more common form with a flat bottom, narrow neck, and flared opening, such as the Arsenal Pottery model shown in the slideshow, to those that purposely disguise the vessel’s use, such as the tortoise, also shown here, in which the repository is hidden under the reptile’s shell.