For British potters, the 1840s represented the first sustained period of immigration to the United States. This shift was due in part to a prolonged economic downturn in the English ceramic trade, which had resulted in a high level of unemployment among both skilled and unskilled workers. At the same time, potters in Britain were enticed by the potential for higher wages and improved working conditions, and by persuasive notions of America as a bountiful country, full of financial and material promise. Equipped with the necessary training and knowledge of production techniques, these immigrant potters were critical to building a successful ceramic manufacturing industry in the United States. Many of them were not master potters and worked as journeymen in established American potteries; others provided skills and know-how, partnering with investors who supplied the necessary financial resources to set up viable businesses. Those with adequate capital struck out on their own, several founding potteries that specialized in making majolica.

By the mid-1870s, the commercial success of imported majolica had captured the attention of US manufacturers and the many British potters who continued to immigrate to this country. Eager to profit from its popularity, American potteries began to produce majolica jugs, spittoons, tea sets and other tableware. Most did not create designs based on historical styles or ornament, nor did they engage named artists or sculptors. Instead, these US firms focused on producing designs that would enjoy wide appeal among consumers, typically with ornament inspired by nature. Many potteries replicated best-selling English models as is shown in the pairings displayed here. Copying popular designs was, in fact, a common practice across the industry on both sides of the Atlantic.

Left

Athletic Jug, pattern no. M2836

Charles Toft (1831–1909), designer

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

This example 1879

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Right

“Base Ball” Jug, shape no. E6

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection

Left

Athletic Jug, pattern no. M2836

Charles Toft (1831–1909), designer

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, manufacturer

This example 1879

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Joan Stacke Graham Collection

Right

“Base Ball” Jug, shape no. E6

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection

The Phoenixville, Pennsylvania–based firm of Griffen, Smith & Co. drew on many English sources for design inspiration. An Englishman with the last name Bourne, possibly Hamlet Bourne (1852–1899), an itinerant ceramic modeler and son of a chief designer at Wedgwood, worked at Griffen, Smith & Co. during the 1880s. Given this direct link to one of England’s main producers of majolica, it is not surprising that many of the Phoenixville firm’s designs are almost exact copies of Wedgwood models. The Griffen, Smith & Co. “Base Ball” Jug is an example of a near copy of a Wedgwood design—although in the American version, the cricketers have been replaced with baseball players, reflecting the popularity of “the national pastime” on this side of the Atlantic.

Left

“Bramble” teapot, pattern no. M2903

Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire

Designed ca. 1878; this example 1879

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Right

“Bramble” teapot

D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland

ca. 1882–86

Earthenware with majolica glazes

The English Collection

The “Bramble” pattern by Baltimore’s Chesapeake Pottery is a copy of a design by the same name introduced by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons a few years earlier. The Chesapeake and Wedgwood teapots shown here exhibit only slight differences in molding, size, and color. While both feature an ivory ground glaze, which originated in the English design, the Baltimore version’s colors are noticeably brighter, and its handle and spout are painted in a mottled combination of greens and browns.

Read More

The Migration of English Potters to the United States

Miranda Goodby

James Carr’s New York City Pottery

As majolica mania spread to the United States, several American potteries began making the ware in the mid-1870s. The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia gave the US ceramic industry the opportunity to showcase its progress in design and manufacturing. Among the varied products on view at this world’s fair were exhibits by more than sixty domestic potteries, three of which included majolica. The most extensive majolica display was presented by James Carr (1820–1904), proprietor of the New York City Pottery, which operated between 1855 and 1889 from West 13th Street, near the busy Hudson River piers in Manhattan. Carr’s 1876 presentation featured both original designs expressing a strong American identity and copies of popular English models. Indeed, most US makers attempted to strike a balance between innovation and imitation, as salability and profitability were key to sustaining their businesses.

Born and trained in England, Carr came to the United States in 1844 as part of the wave of British potters to immigrate here during the 1840s, a group that invigorated the country’s nascent ceramic industry. Carr’s life story, published three years before his death, offers a rare glimpse into the many struggles immigrant potters-turned-entrepreneurs faced as they established businesses in a new country—from shortages in skilled labor, capital, and materials, to the challenges of strikes, fire, and the influx of cheap imported wares.

Centennial Photographic Co.

James Carr’s New York City Pottery display, Main Building, Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition

1876

Stereograph

Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 93516795.

Majolica made at James Carr’s New York City Pottery set high standards in terms of quality and artistic merit. The firm had long excelled in manufacturing utilitarian ceramics, and combined its sturdy earthenware body with rich glaze colors such as the “Mazarine” blue on the covered jar seen here. The whimsical container hoisted by a trio of frogs promotes the “Vanity Fair” pipe tobacco produced by William S. Kimball & Co. of Rochester, New York. While not visible in the only known photograph of his stand, Carr displayed this piece among his other offerings at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, as is recorded in a chromolithograph published after the close of the fair.

Right

Centennial Photographic Co.

James Carr’s New York City Pottery display, Main Building, Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition

1876

Stereograph

Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 93516795.

Majolica made at James Carr’s New York City Pottery set high standards in terms of quality and artistic merit. The firm had long excelled in manufacturing utilitarian ceramics, and combined its sturdy earthenware body with rich glaze colors such as the “Mazarine” blue on the covered jar seen here. The whimsical container hoisted by a trio of frogs promotes the “Vanity Fair” pipe tobacco produced by William S. Kimball & Co. of Rochester, New York. While not visible in the only known photograph of his stand, Carr displayed this piece among his other offerings at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, as is recorded in a chromolithograph published after the close of the fair.

Griffen, Smith & Hill Company, Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

The firm founded as Griffen, Smith & Hill Company in 1879 and renamed Griffen, Smith & Co. in 1880, produced its high-quality “Etruscan Majolica” until the early 1890s in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, a town located about thirty miles northwest of Philadelphia. Under the management of Phoenixville natives George Griffen (1854–1893) and his brother Henry Griffen (1857–1907), and Staffordshire-trained potters David Smith (1839–1895) and William Hill (1837–1913), the firm’s range of majolica was the largest of any American ceramic manufacturer. Though many of its designs were derived from English models, the company’s distinctive glazes were formulated in-house and admired for their vibrancy and richness.

The firm actively marketed and promoted its wares. It advertised regularly in trade journals, issued illustrated catalogues, and participated in the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition of 1884–85 in New Orleans. Griffen, Smith & Co. exhibited more than 150 pieces of majolica as well as other types of earthenware at this world’s fair, including a faience garniture that was awarded a second-place medal. The pottery also engaged in premium programs with the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P) and the Edward Canby company, supplying both with majolica to be given away with the purchase of coffee, tea, or baking powder. While these associations substantially increased the firm’s revenue, they also may have led to the devaluation of Etruscan Majolica, which in turn, may have contributed to the demise of the business.

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection

Following the extensive display of Japanese fine and decorative arts at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia, American enthusiasm for the arts of Asia grew exponentially. It also flourished under the influence of the Aesthetic movement, which promoted Japanese and Chinese objects and motifs—or those inspired by them—as fundamental elements in the making of an artful home. Naturalistic bamboo decoration was popular and widely incorporated, including by Griffen, Smith & Co. in its majolica.

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, most ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Griffen, Smith & Co., Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

ca. 1879–90

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, most ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

Griffen, Smith & Co.’s “Shell” ware was relatively expensive, and yet it remained one of the firm’s most popular offerings. Likely inspired by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons’s “Ocean” and “Shell” majolica wares, as well as shell designs executed in porcelain by the Irish company Belleek, Griffen, Smith & Co.’s pattern features naturalistic scallop shells in various combinations accented with seaweed, coral, whelks, and other small shells. The line was the firm’s most extensive as is evidenced by the range of forms shown here.

The “Staffordshires” of America: East Liverpool, Ohio, and Trenton, New Jersey

In the decades preceding the Civil War (1861–65), between 40 and 50 percent of the ceramic ware exported from Staffordshire was sold to American consumers. Although there were earlier small-scale efforts made in the United States to capture some of this ever-growing domestic market, the first true emergence and consolidation of the American pottery industry occurred in the 1840s in East Liverpool, Ohio, a town forty miles west of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A confluence of natural resources made East Liverpool an ideal setting for ceramic production: large deposits of clay suitable for making pottery, especially yellow-bodied earthenware (yellowware); coal in close proximity that could be easily mined to fire the kilns; and its location on the Ohio River, a ready means to transport goods to market. The town became a magnet for North Staffordshire potters wanting to emigrate, and by 1850, more than 70 percent of the East Liverpool workforce was English-born and employed in ceramic manufacturing, the city’s dominant industry.

Trenton’s development as a pottery manufacturing center began about a decade later, in the 1850s, and was likewise reliant on immigrant labor and enterprise. White-bodied wares, or whiteware, dominated early ceramic production, which initially gave the New Jersey potteries a commercial advantage over East Liverpool. When the Ohio potteries undertook whiteware manufacture in the 1870s, an intense rivalry between the two centers was sparked. Indeed, both publicly claimed to be “the Staffordshire of America,” not only to establish their stature within the domestic industry, but also to reflect what was the dominant trade of both regions.

Although majolica was but a mere fraction of the goods made in either place, the legacy of its production demonstrates the successful integration of English processes and techniques within an American manufacturing context.

Read More

George Morley and the Potteries of East Liverpool, Ohio

Laura Microulis

Majolica Made in Trenton, New Jersey

Laura Microulis

Morley & Co., Wellsville and East Liverpool, Ohio

Born and trained in Stoke-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, George Morley (1829–1896) immigrated to the United States in 1848, and by about 1853, had settled in the burgeoning pottery manufacturing center of East Liverpool, Ohio. His most successful commercial venture was the Salamander Pottery, a partnership that was active from 1858 to 1878. Using local clay, Salamander produced utilitarian yellow-bodied earthenware, or yellowware—some of which was decorated in rich mottled-brown, or Rockingham, glazes. By the early 1870s, the firm had turned to the production of more refined white-bodied wares, also known as whiteware.

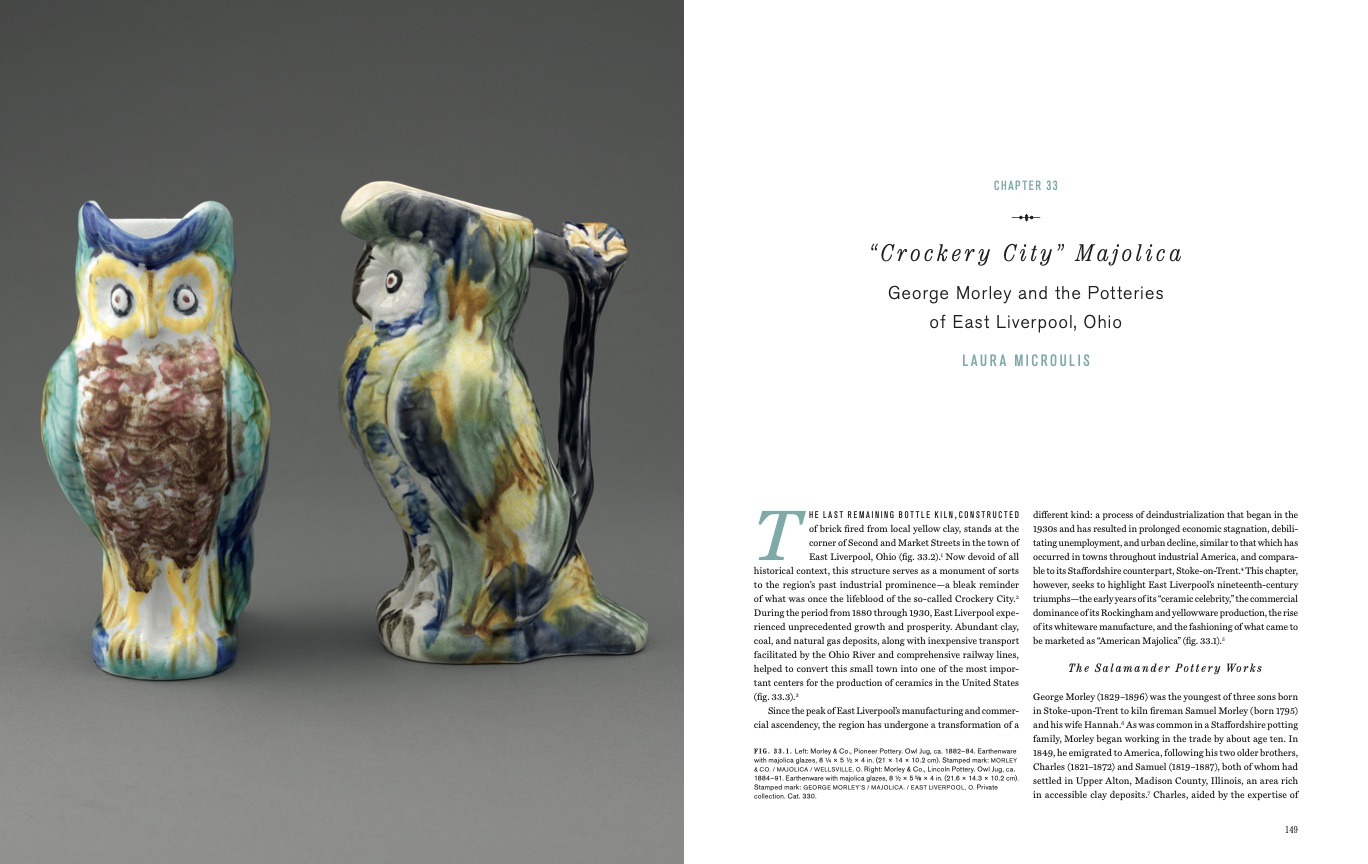

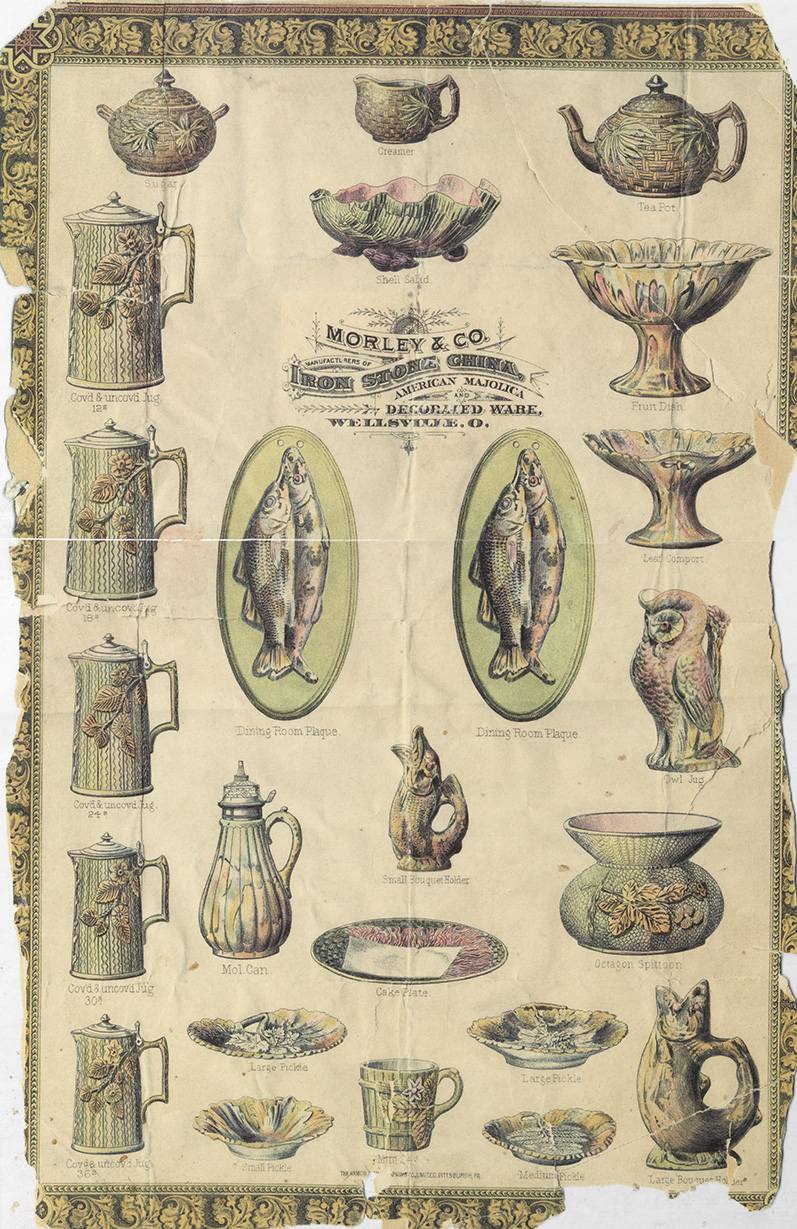

Morley established two successive firms that produced majolica: the Pioneer Pottery in Wellsville, Ohio, in 1879 and the Lincoln Pottery in East Liverpool in 1884. He marketed the wares produced by both as “American Majolica,” no doubt a sign of his patriotism, but perhaps also to differentiate his use of a white granite or ironstone body from the more typical buff-colored clays employed by most other majolica makers. The firm utilized this branding in its printed advertisements and in at least one illustrated pattern sheet, which is shown below.

Click the objects in the pattern sheet below to see examples of Morley & Co. majolica.

Armor Lithographing Co., Limited, printer

ca. 1882

Lithograph

William and Donna Gray

Click Objects Above to Explore

Armor Lithographing Co., Limited, printer

ca. 1882

Lithograph

William and Donna Gray

The Owl Jug introduced by Morley & Co. in the summer of 1882 is a close copy of a model produced by the Staffordshire firm of Thomas Forester, which in turn, was a modified version of a jug in the form of a cockatoo by Shorter & Boulton, another English pottery. This complex line of design transmission, while not officially sanctioned within the ceramic trade, was common practice in both Britain and the United States. Those Staffordshire firms, such as Forester and Shorter & Boulton, that specialized in the manufacture of lower-price wares, many of which were imported into the United States, were generally serving the same demographic as many American potteries. Protective tariffs raised the price of imported English majolica and rendered the cost of American copies competitive, making the replication of popular British designs a sound business practice for US manufacturers.

Eureka Pottery Co., Trenton, New Jersey

Philadelphian Leon Weil (1844–1907) started the short-lived Trenton firm Eureka Pottery Co. in early 1883. Despite his lack of previous experience in the ceramic industry, within a few months, he had hired twenty women decorators, or “paintresses.” The pottery copied fashionable English majolica models, particularly those employing the sort of Japanesque designs considered important expressions of Aesthetic movement taste. Despite the relatively high-quality execution of its majolica, the Eureka Pottery closed after one year of operation.

Eureka Pottery Co., Trenton, New Jersey

1883

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Donna and Mickey Louis

Despite efforts to expand design education, there was an acknowledged scarcity of trained modelers working in the American pottery industry in the 1870s and 1880s, one of several factors that led firms to copy one another’s designs. Eureka’s “signature” ware—plates, comports, and other forms embellished with a Japanesque bird in flight and plum blossom branch on a textured ground—were, in fact, derived from models introduced by the Staffordshire firm of Shorter & Boulton.

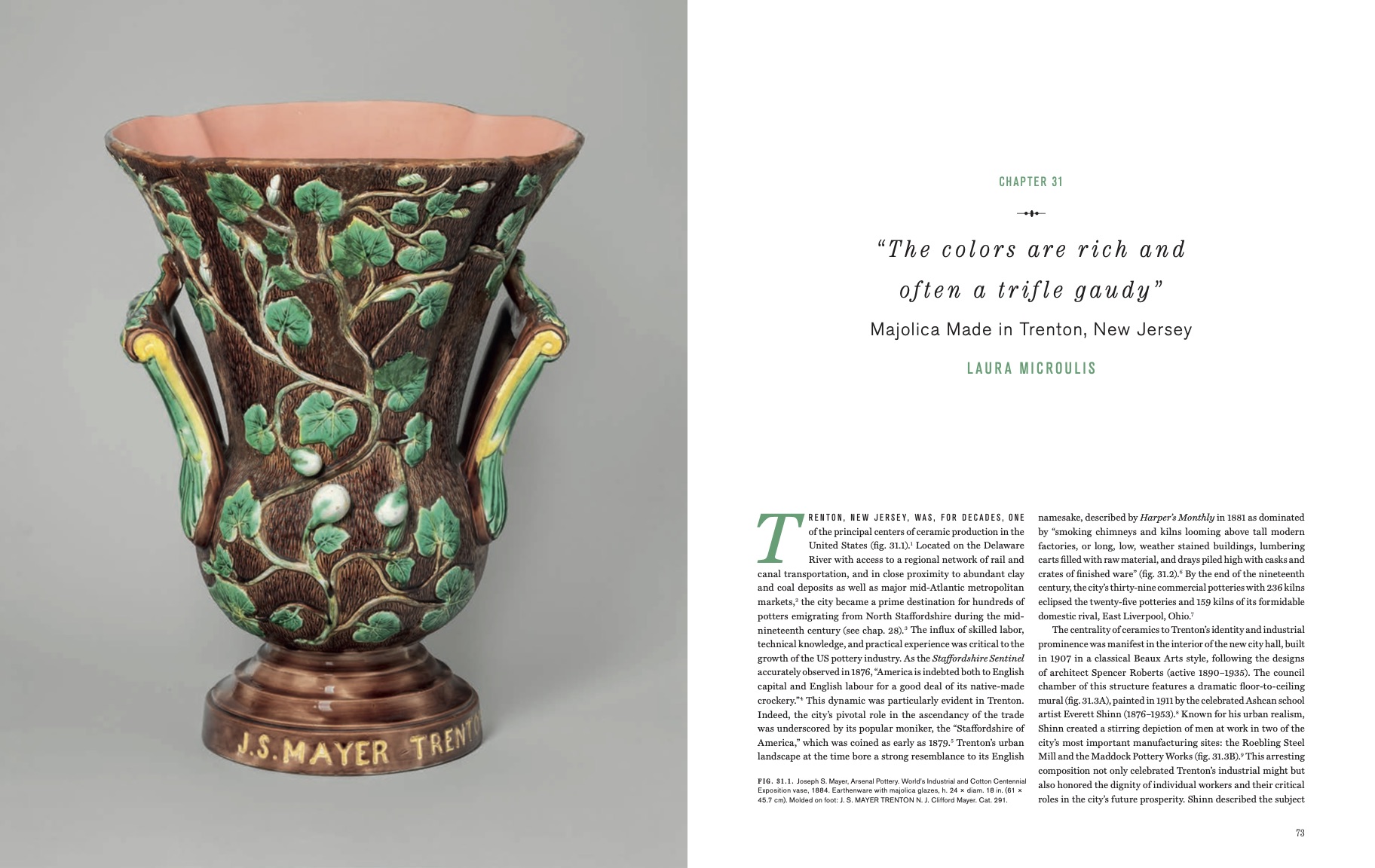

Joseph S. Mayer’s Arsenal Pottery, Trenton, New Jersey

The Arsenal Pottery was founded in 1876 by Joseph S. Mayer (1846–1907), an English-born-and-trained potter and inventor, as well as a consummate salesman. Initially, the firm produced other types of earthenware, specifically the mottled-brown ware known as Rockingham as well as yellow-bodied ware, or yellowware. By 1882, following the arrival of Mayer’s older brother James (1841–1883), who had a “chemical knowledge of colors” that he applied to the formulation of glazes, the pottery had begun to make majolica.

As a high-volume producer of low-cost wares, Mayer employed a strategy aimed at making majolica accessible to the masses—an approach that made him, at one time, a very wealthy man and an important figure in the ceramic history of Trenton. The plates and jugs that his firm produced are the kinds of decorative wares that adorned the parlors and dining tables of middle- and working-class Americans in the 1880s and 1890s. The plant and animal motifs are suggestive of the nineteenth-century notion that proximity to nature, whether real or manufactured, would make the home a healthy, nurturing environment. Most of these designs were available in a range of color combinations, further expanding Arsenal Pottery’s majolica offerings, which the firm produced well into the 1890s.

Click Objects Above to Explore

Joseph S. Mayer, Arsenal Pottery

1885

Colored woodcut and pencil mounted in bound album

Huston Bennett scrapbook and catalog, MS 3236, H. Furlong Baldwin Library, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore

Joseph S. Mayer’s motto “everybody wants a jug” reflects the Arsenal Pottery’s commercial strategy to satisfy market demand through the manufacture of low-cost goods at high volume. Many of the firm’s majolica wares were copies of models made by well-known English manufacturers, including its Tea Jug and Marine Jug, which were derived from prototypes introduced by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons and Wardle & Co., respectively.

Click the illustrations in the pattern sheet above to see examples of Arsenal Pottery’s jugs.

Majolica in Baltimore

Baltimore developed into an important commercial center and port over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Founded in 1729 on the Chesapeake Bay, the city was ideally situated for Atlantic maritime trade, and as manufacturing grew, its reach expanded westward with the opening in 1830 of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The surrounding region contained significant deposits of clay, flint, and other raw materials, as well as access to coal—resources essential to the development of a ceramic industry. As a major port of entry, second only to New York, Baltimore welcomed the many European migrants who ensured a steady supply of labor. All of these factors contributed to the success of Baltimore’s potteries in the late nineteenth century.

Majolica Made in Baltimore, Maryland

Earl Martin

D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore importer and wholesaler David Francis Haynes (1835–1908) purchased the Chesapeake Pottery in 1882. He hired seasoned Staffordshire potters to manage the works, including Frederick Hackney (1848–1892). Hackney had trained at Wedgwood, a leading English majolica manufacturer, and subsequently was a partner in Hackney, Kirkham & Co., the precursor to S. Fielding & Co., which specialized in making the colorful earthenware. Chesapeake Pottery made a variety of wares from 1882 until 1912, but majolica was a mainstay in the firm’s early years. Many of the Baltimore company’s patterns and decorations were adapted from English prototypes, especially those of Josiah Wedgwood & Sons.

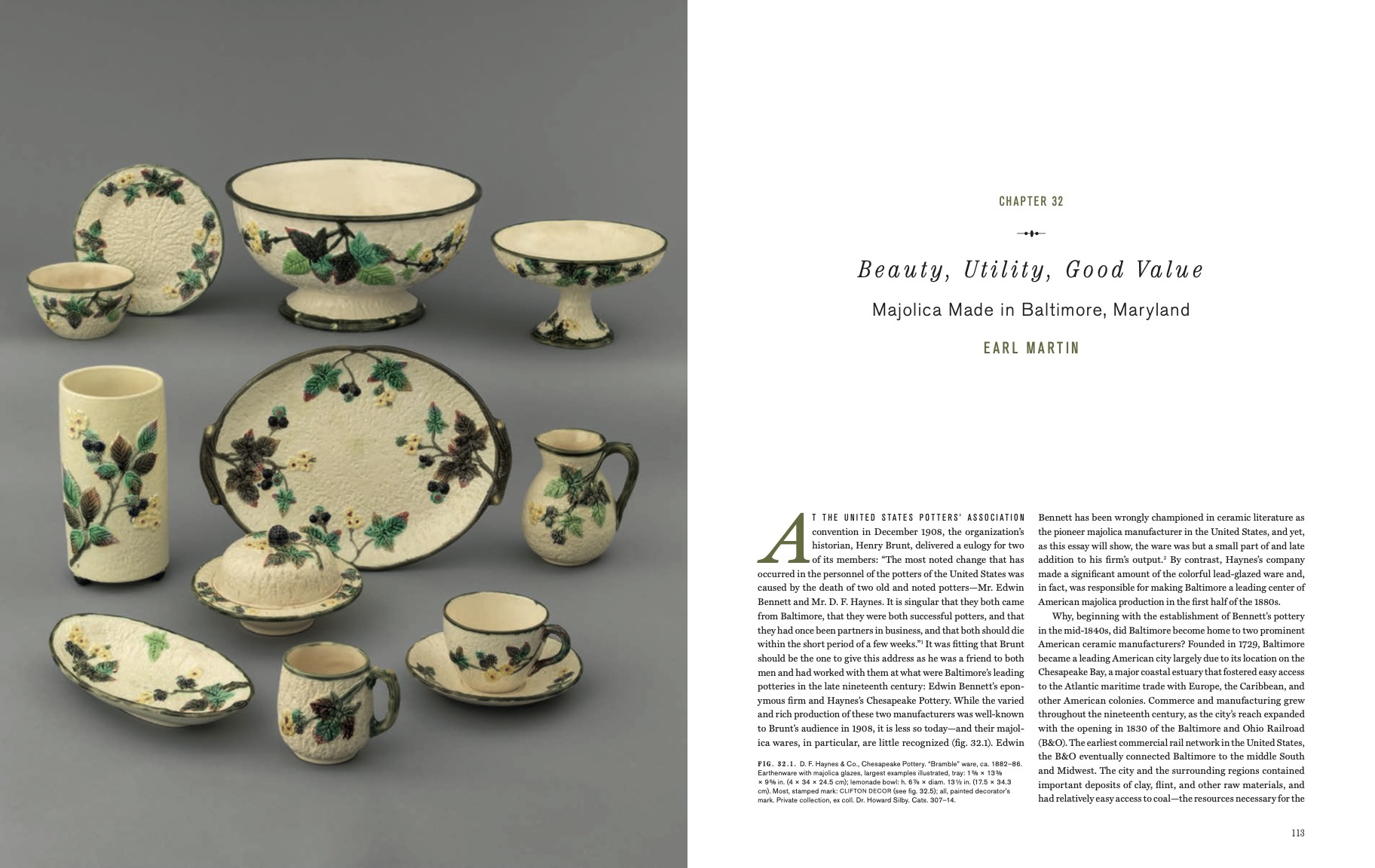

D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland

ca. 1882–86

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland

ca. 1882–86

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby

By February 1883, D. F. Haynes & Co. was advertising a new addition to its majolica line—a “Strawberry” jug. Chesapeake’s inspiration seems to have come from a Wedgwood prototype of the late 1870s. Many English and American manufacturers made patterns featuring strawberry motifs, as well as wares used to serve the spring fruit, in response to the popularity strawberries enjoyed during this time.

Case: D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland; mechanism: New Haven Clock Company, New Haven, Connecticut

ca. 1883–86

Earthenware with majolica glazes, brass, wood, and other materials

Private collection

In 1883, the Chesapeake Pottery introduced Calvert ware, a line of decorative objects including vases, jugs, and clocks like the one shown here. Finished in solid-color majolica glazes in response to the period fashion for monochromatic wares, the line was widely praised in the trade press and carried by exclusive retailers including Tiffany & Co. in New York City.

Case: D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland; mechanism: New Haven Clock Company, New Haven, Connecticut

ca. 1883–86

Earthenware with majolica glazes, brass, wood, and other materials

Private collection

In 1883, the Chesapeake Pottery introduced Calvert ware, a line of decorative objects including vases, jugs, and clocks like the one shown here. Finished in solid-color majolica glazes in response to the period fashion for monochromatic wares, the line was widely praised in the trade press and carried by exclusive retailers including Tiffany & Co. in New York City.

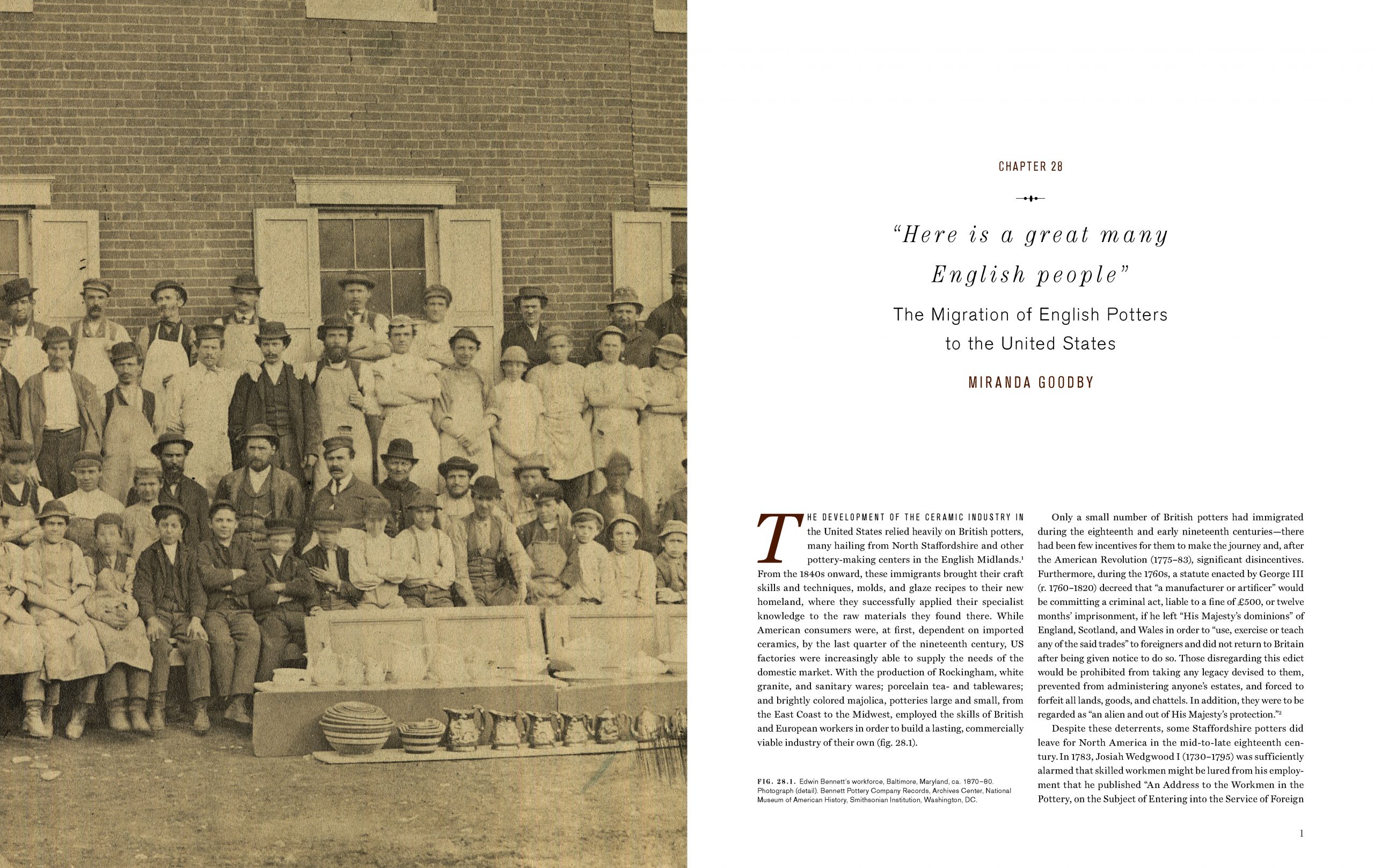

Edwin Bennett Pottery Company, Baltimore, Maryland

Edwin Bennett (1818–1908) was the oldest American pottery manufacturer at the time of his death and rightfully hailed as a pioneer of the industry. Following an apprenticeship, he worked for several years in the pottery industry in his native Derbyshire, England, before immigrating to the United States in 1841 with two of his brothers to join a pottery founded by a third brother in East Liverpool, Ohio. By 1846, Edwin Bennett had moved to Baltimore and started his own factory, where he built up a successful business that largely made utilitarian table- and kitchenwares. The firm introduced some decorated wares, including majolica, in the late 1870s or early 1880s. In 1890, Bennett hired Staffordshire native Henry Brunt (1852–1915) as manager. Brunt had worked at Minton and George Jones before coming to Baltimore in 1886 to work at Chesapeake Pottery. Under Brunt’s direction, the firm began to produce a small number of artistic wares, some of which were finished in monochrome majolica glazes.

Herbert W. Beattie (1863–1918), designer

Edwin Bennett Pottery, Baltimore, Maryland, manufacturer

ca. 1893

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Maryland Historical Society, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin Bennett Filbert, 1973.112.29

English-born-and-trained modeler Herbert W. Beattie was hired to create this impressive Neoclassical pedestal model for the Bennett display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Over the next few years, the firm featured the object in company literature, where it is described as a “Fern Stand” available in blue, yellow, and other colors—although it is unlikely that more than a few were made. A tour de force of ceramic art, this example was given by the Bennett family to the Maryland Historical Society in 1973.

Peekskill Pottery Works, Peekskill, New York

Richard Harrison (1819–1901), founder of the Peekskill Pottery Works, was born in Staffordshire, England, where he trained as a potter—as had his father and siblings, all of whom immigrated to the United States in 1844. A tireless entrepreneur, Harrison made his way through America’s major ceramic centers, founding and closing a series of potteries before finally settling in Peekskill, New York, a Hudson River town located fifty miles north of New York City.

By 1878, he was operating a single kiln and likely formulating glazes in-house. Moreover, given the consistency and originality of the designs, Harrison (or perhaps one of his two sons) was probably also modeling his firm’s ware. Peekskill majolica designs are refreshingly inventive and often aesthetically quirky. Most pieces are impressed with the enigmatic maker’s mark: TENUOUS MAJOLICA.

Peekskill Pottery Works, Peekskill, New York

1878–ca. 1894

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice

Peekskill Pottery Works, Peekskill, New York

1878–ca. 1894

Earthenware with majolica glazes

Rena and Sheldon Rice