Blenko Glass Company

Milton, WV

Cullet Bins, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Introduction

Blenko Glass Company, located in Milton, West Virginia, is a family-owned glass factory specializing in hand-blown sheet glass, architectural glass, and tableware. The firm dates back to 1893, when founder William J. Blenko began making colored plate glass for use in stained glass windows. The company added decorative objects and tableware to its line during the economic depression of the 1930s, hiring European craftsmen to design new products and teach Blenko’s skilled glassblowers how to make them by hand in quantity. The company’s origins in stained glass underlay its successful pivot toward making tableware, which it produced in a wide range of vibrant colors. By the 1950s and 1960s, tastemakers and consumers regarded Blenko’s elegant pieces in bold, single hues as desirable objects of modern design. Blenko glass was featured in major museum exhibitions and entered public and private collections. Later, the company fostered the development of American studio glass by hiring artists to serve as designers, thus helping sustain or launch their careers; at times outside artists also used its facilities. Additionally, Blenko gave large quantities of cullet (scrap glass) to artists and academic programs for free—an important source of raw material at a time when affordable, high-quality glass was hard to find outside of industry.

This section takes a close look at Blenko’s distinctive place in American glass history. It discusses Blenko’s location in West Virginia’s once-thriving glass industry; its craftsmen, manufacturing processes, the designers who attracted critical attention; its engagement with studio glass artists; and the legacy of color and design preserved in its catalogs. The section features interviews and correspondence with Hank Murta Adams, Matt Carter, Dan Dailey, Randall Grubb, Joel Philip Myers, Flo Perkins, Richard Ritter, Dean Six, and Toots Zynsky conducted between 2018 and 2020. It also includes excerpts from a 1981 conversation between Don Shepherd and Paul Hollister, clips from a 1994 video documenting a visit to Blenko by Henry Halem and his Kent State University students, archival material from Blenko and other West Virginia glass companies, and images from the Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Additionally, the section highlights Hollister’s writings on studio glass exhibitions in West Virginia and artists with Blenko connections.

Glassworkers, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1950s or 1960s. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

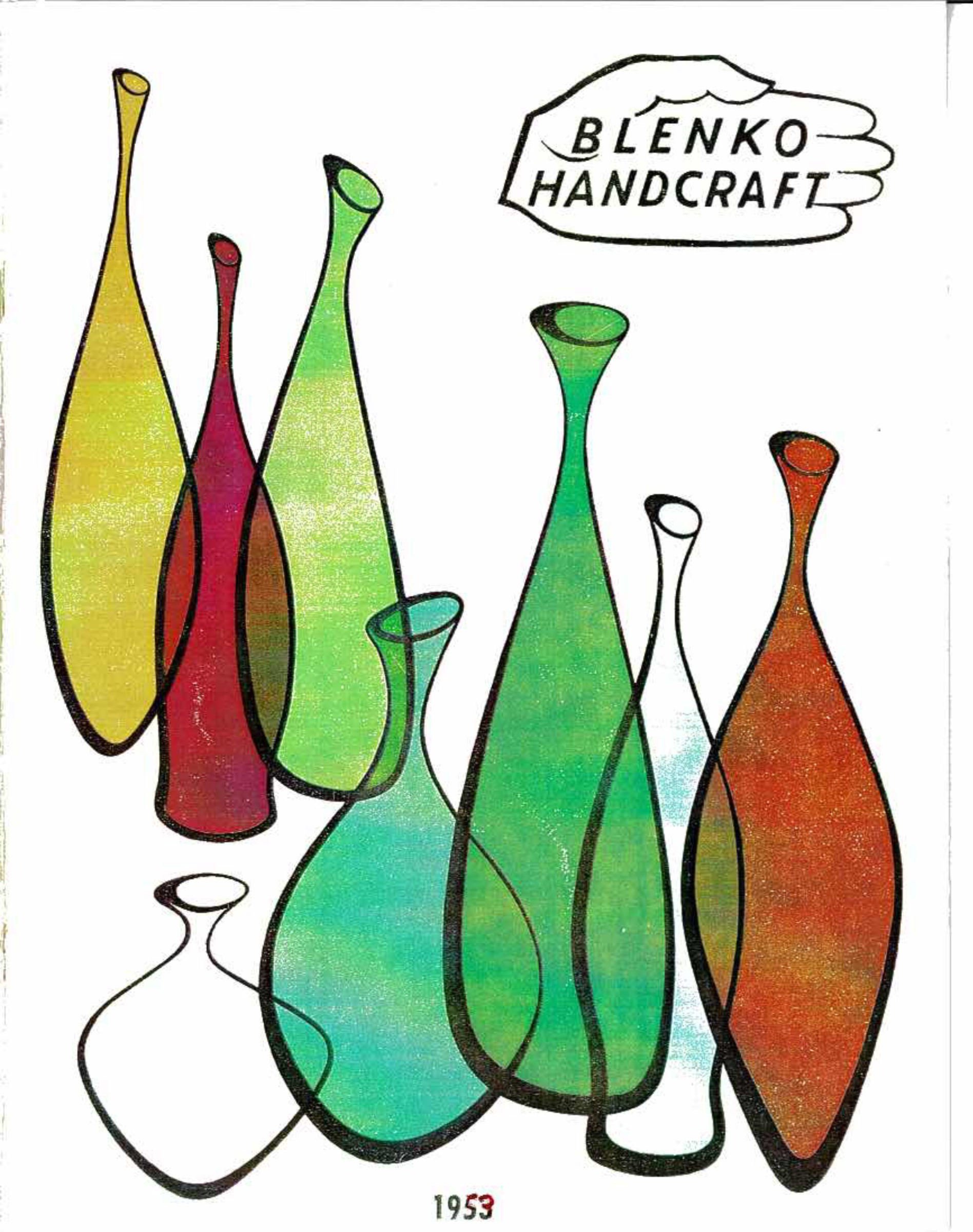

Cover, Blenko Catalog, 1953. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

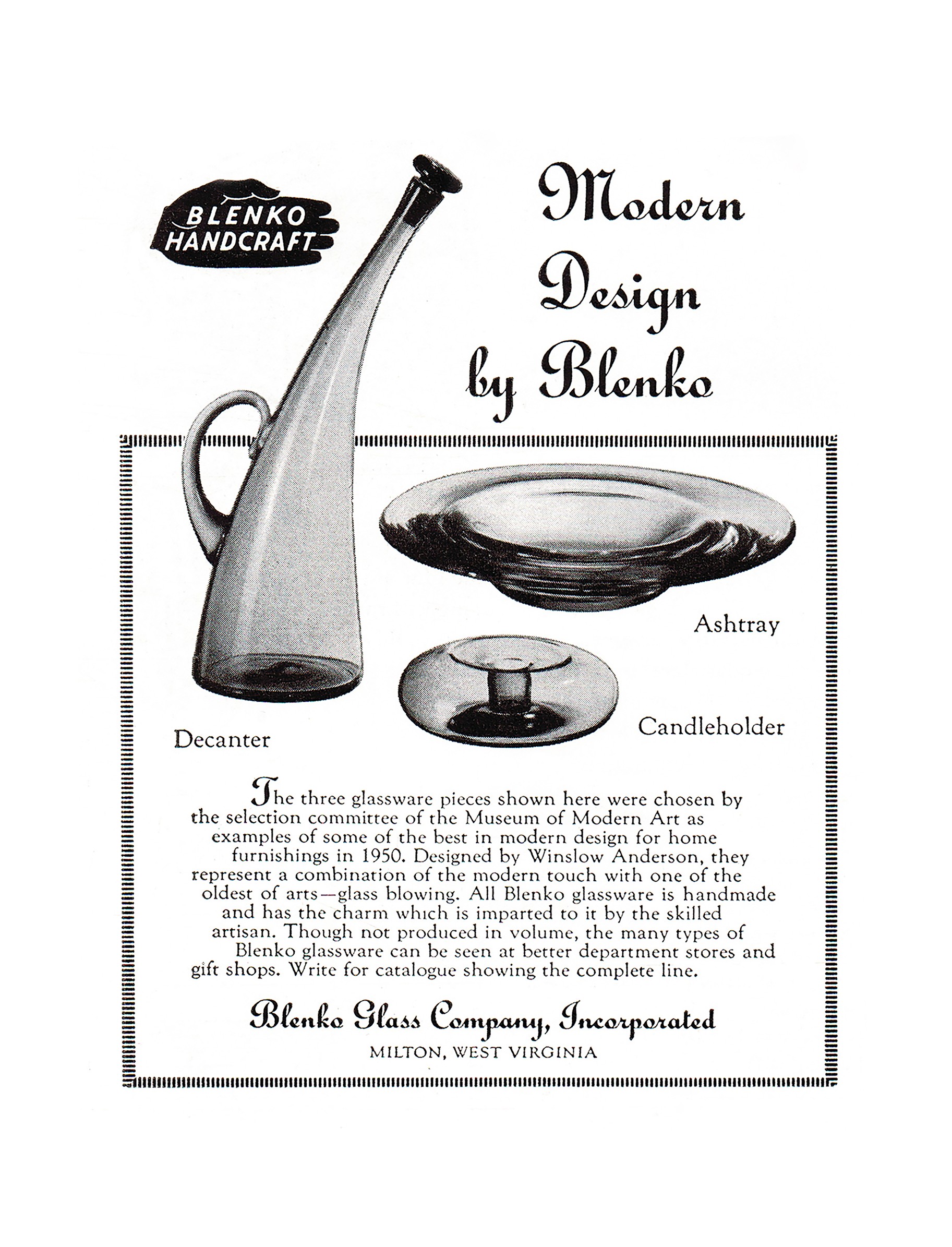

“Modern Design by Blenko” advertisement for Blenko Glass Company featuring three objects selected by the Museum of Modern Art in 1950 as examples of good design for the home. Collection of the American Museum of Glass in West Virginia.(2016.3.103).

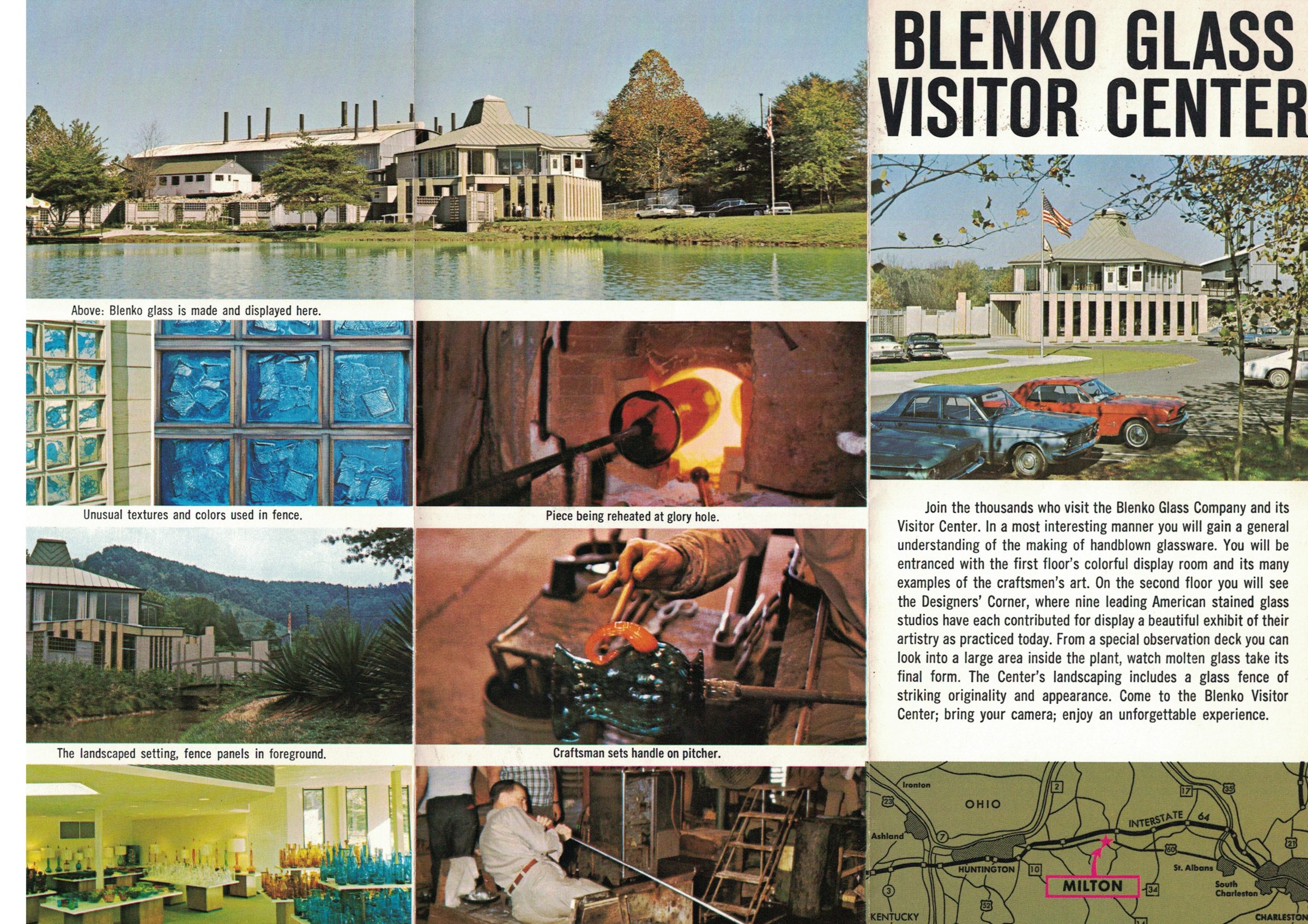

Visitor Center brochure, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1950s or 1960s. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Visitor Center, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 2020. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blenko tableware. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“Blenko was the only U.S. manufacturer of dalle de verre slab glass for years. There are others now, but Blenko was the source for all the mid-century into even current ecclesiastical dalle de verre windows.”

Batch room looking onto silica sand, a main ingredient in glass, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dalle de verre, slab glass used for making stained glass windows, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Shipping area showing windows made with Blenko sheet glass, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Factory exterior, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

The Handmade Industry

Rich deposits of natural gas and silica and access to river and railroad transportation helped make West Virginia a locus of glass manufacturing after the Civil War. By the early 1900s, nearly five hundred glass factories were operating in the tristate region, which encompassed neighboring parts of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Major suppliers of handmade art glass included Pilgrim, Fostoria, Fenton, and Rainbow Art Glass. By 2009, fewer than a dozen companies were still producing, and as of 2020 Blenko is one of the last remaining.

“I have a pretty unique history with the company, and I feel really lucky to have kind of a last hurrah of what it was, and I just feel really like I caught something so special with the American handmade industry and Blenko really was a leader…I think I knew every designer.”

Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

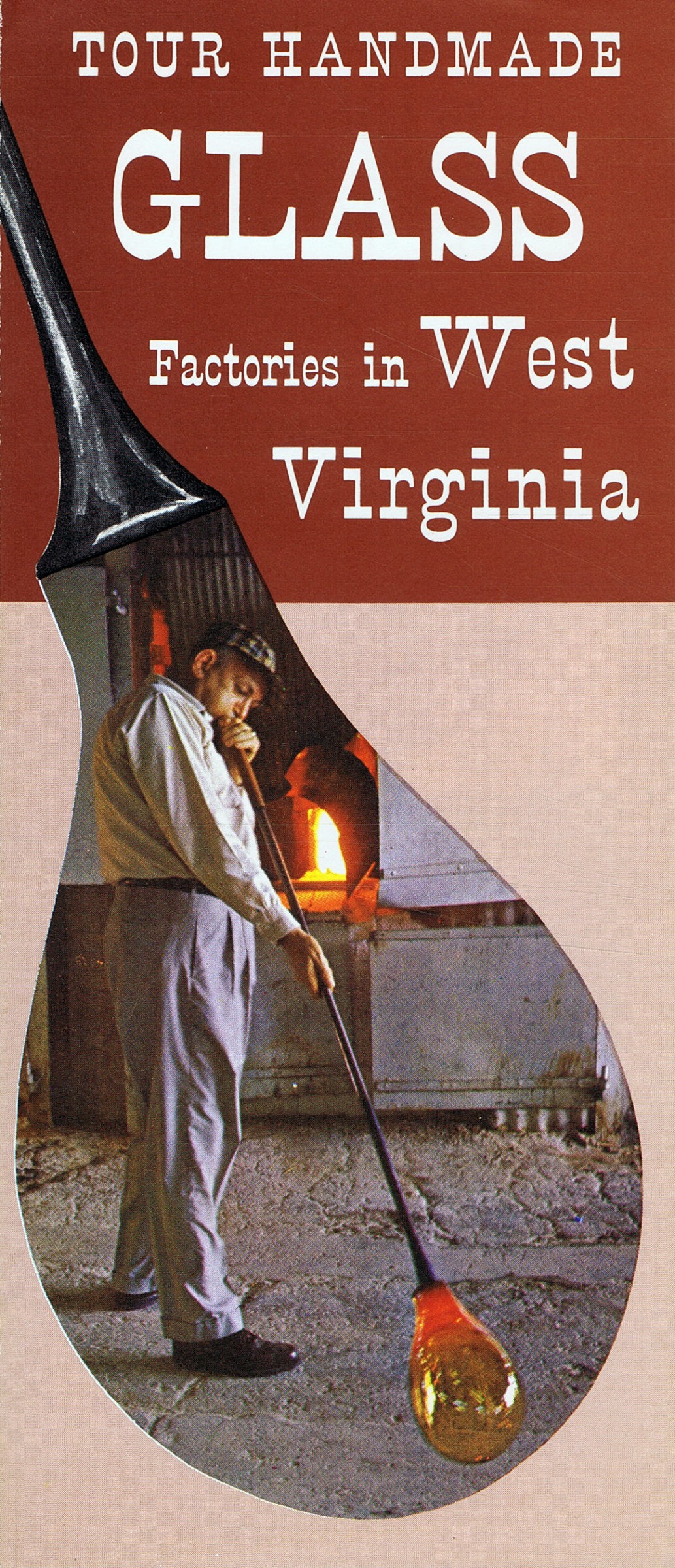

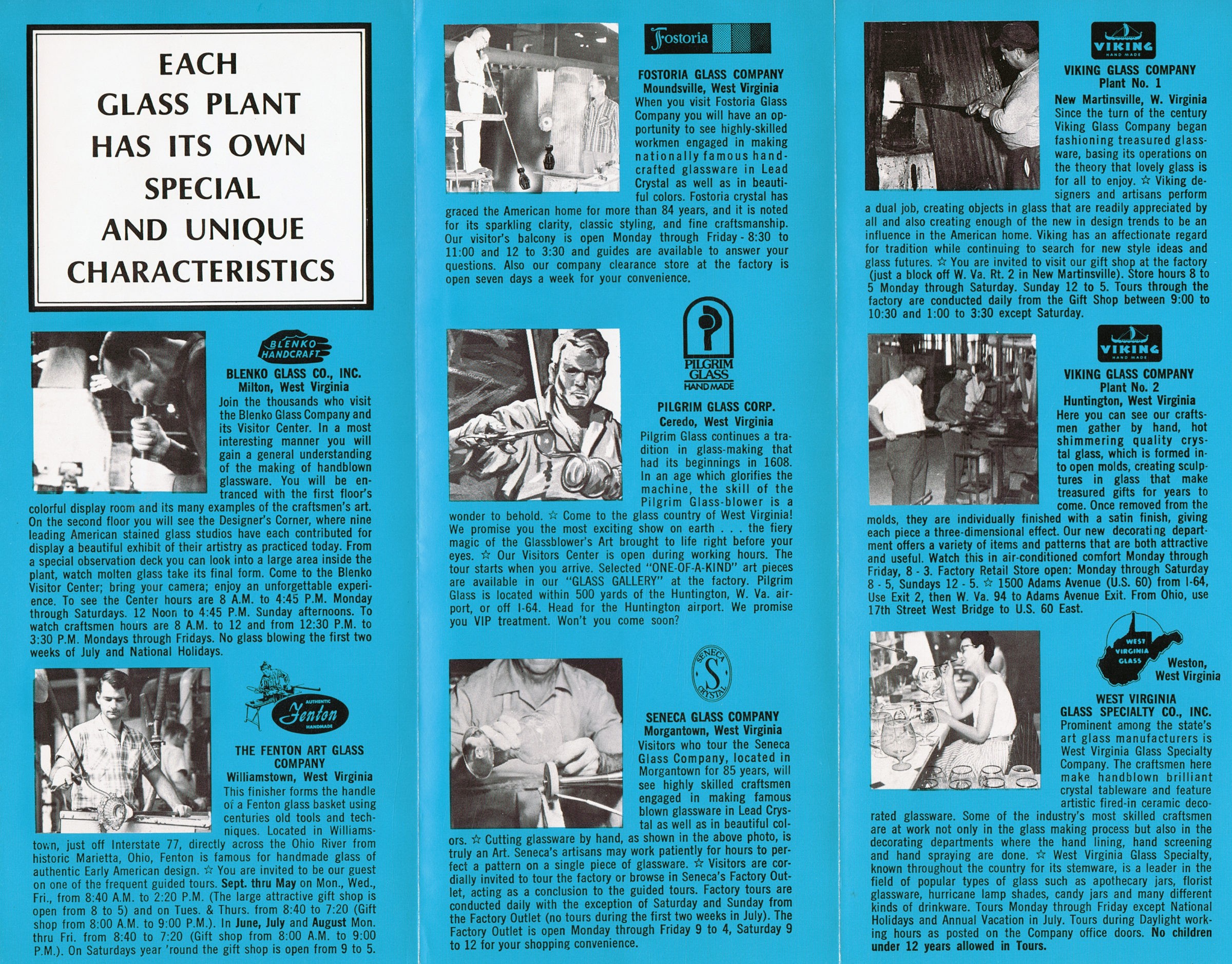

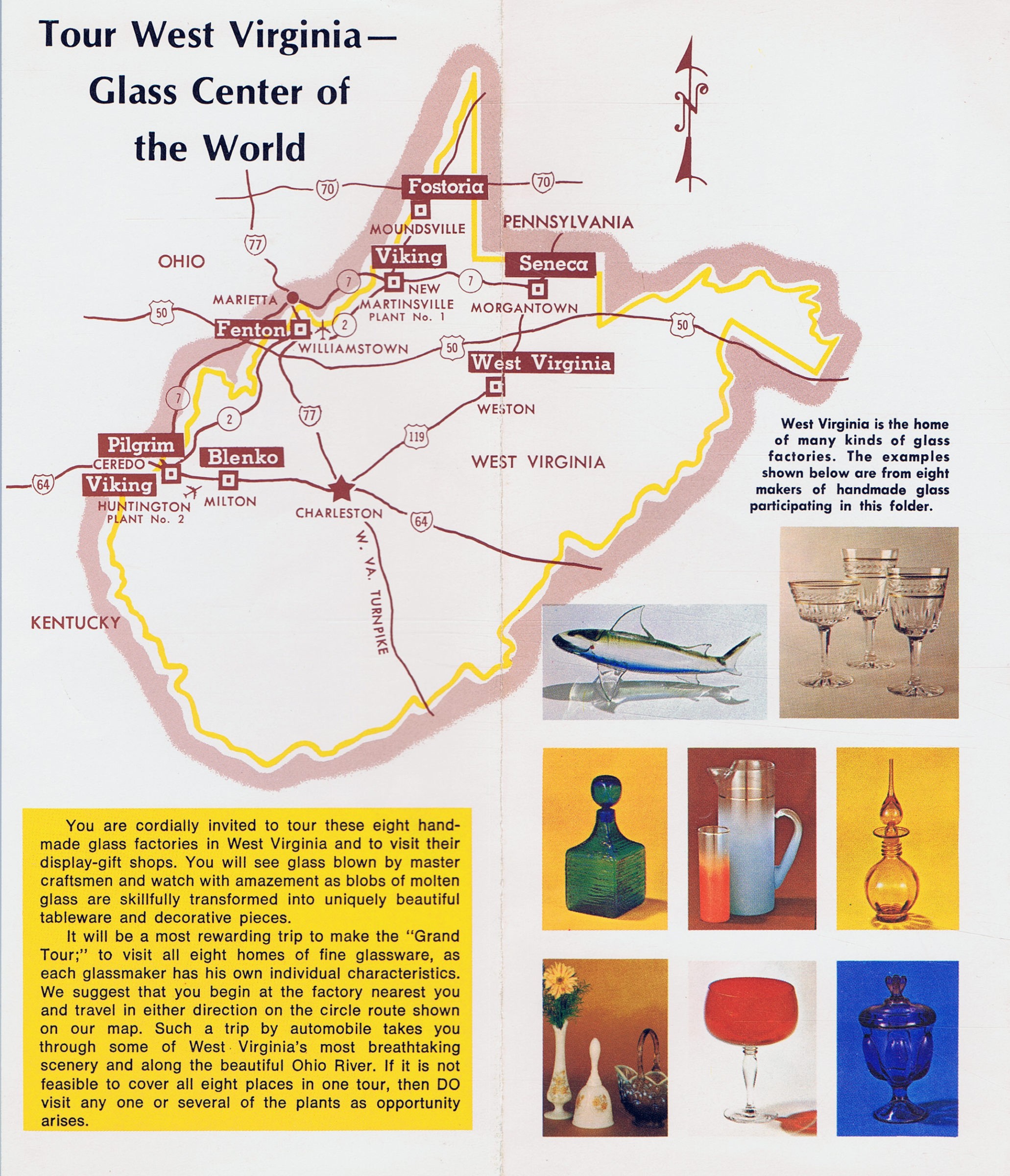

Tour Handmade Glass Factories in West Virginia brochure, c. 1974-1979. Includes Blenko, Fenton, Fostoria, Pilgrim, Seneca, Viking, West Virginia and Glass Specialty. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2017.3.57).

Tour Handmade Glass Factories in West Virginia brochure, c. 1974-1979. Includes Blenko, Fenton, Fostoria, Pilgrim, Seneca, Viking, West Virginia and Glass Specialty. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2017.3.57).

Tour Handmade Glass Factories in West Virginia brochure, c. 1974-1979. Includes Blenko, Fenton, Fostoria, Pilgrim, Seneca, Viking, West Virginia and Glass Specialty. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2017.3.57).

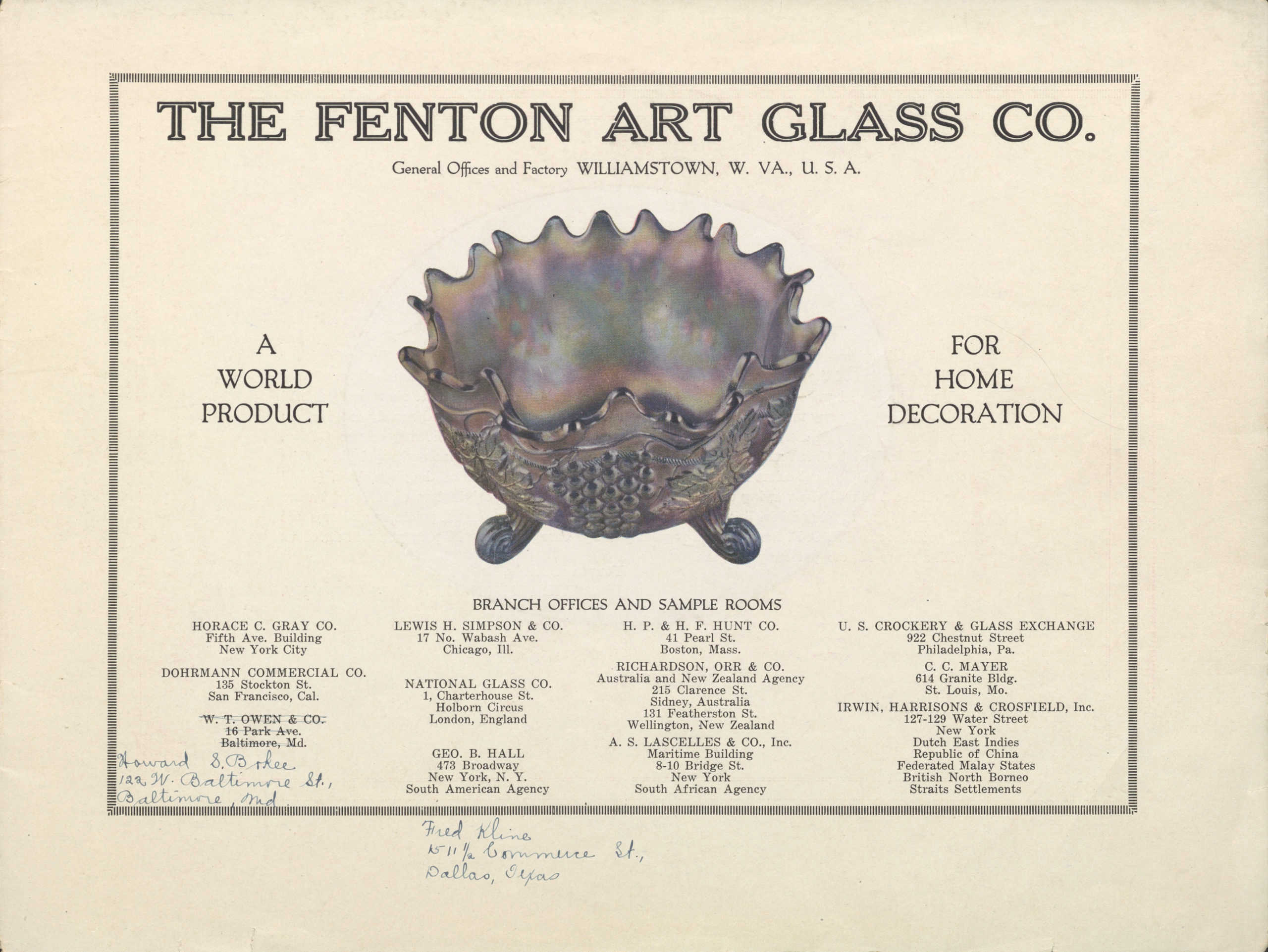

Fenton Art Glass Company trade catalog, title page, 1928. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 87542).

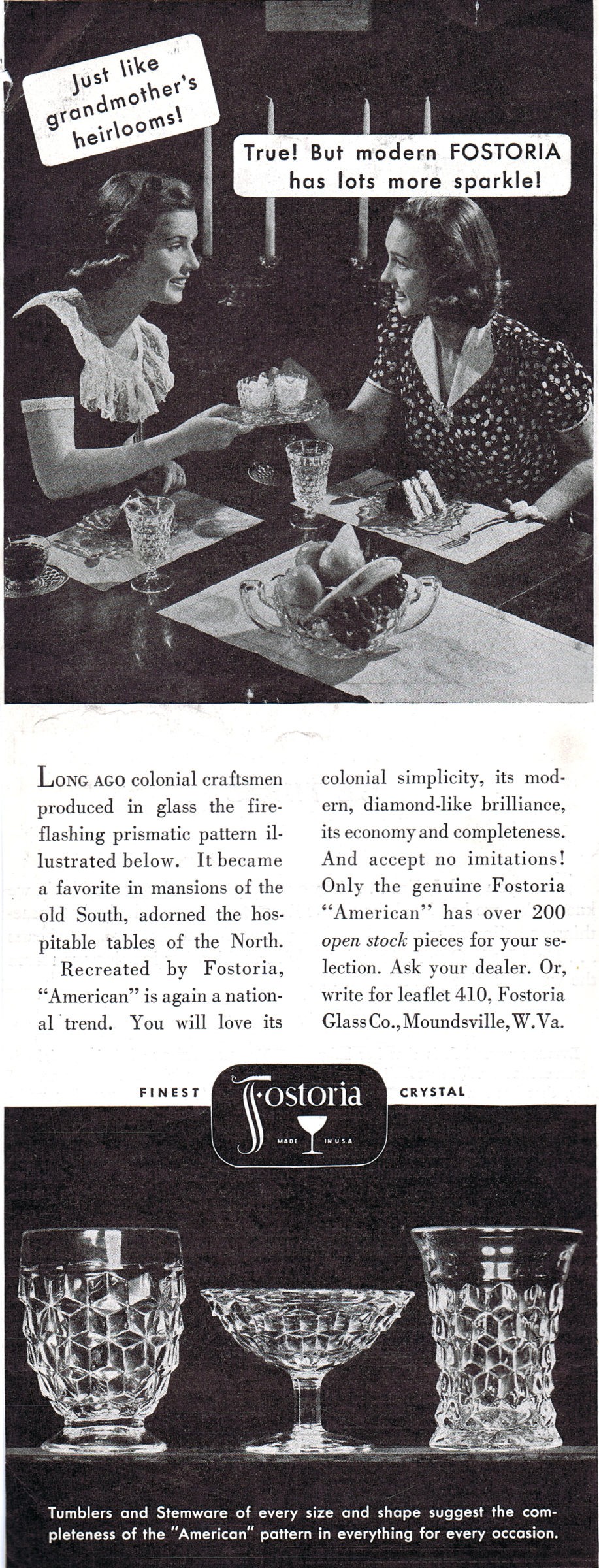

Fostoria Glass Company advertisement, Ladies Home Journal, April 1940. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2020.3.262).

Unidentified West Virginia glassworker (possibly one of the Moretti Brothers), undated. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Glassware, labeled Pilgrim Glass Company, Ceredo, West Virginia, November, 1994. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Mini Pitcher, Pilgrim Glass Corporation, early 1980s. Cranberry and clear glass, Overall H: 4.75 in. Collection of the American Museum of Glass in West Virginia. (2016.76.1).

Glassworker, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, undated. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“That’s the story of our America and our existence and, I’m telling you that most of the information of these factories, I mean, it’s gone. It’s gone.”

Hank Murta Adams discusses the dissolution of the handmade industry in the Ohio Valley.

01:36 TranscriptDesigners

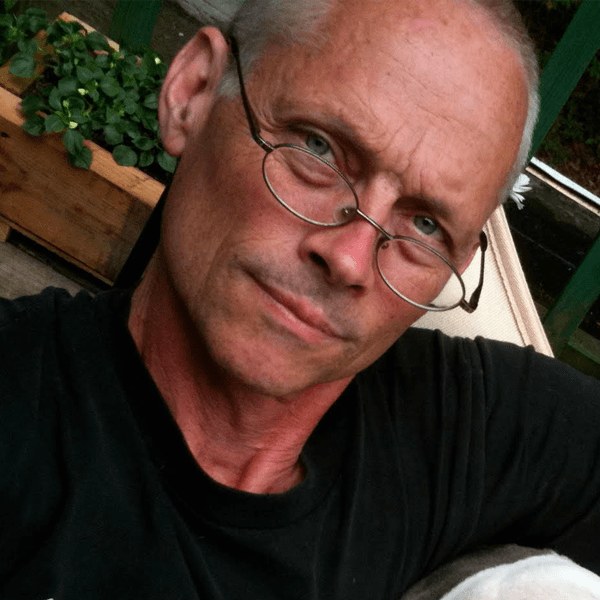

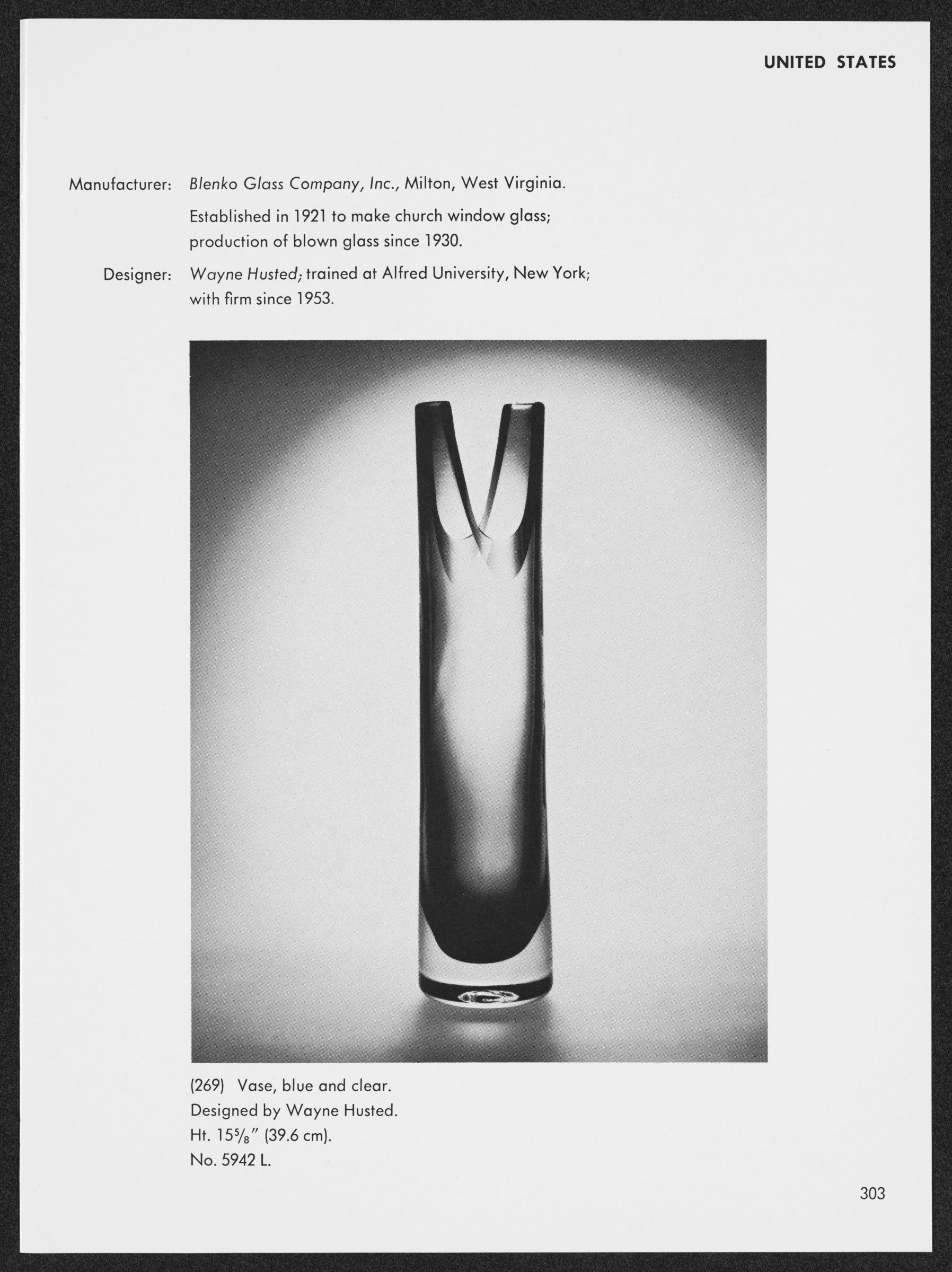

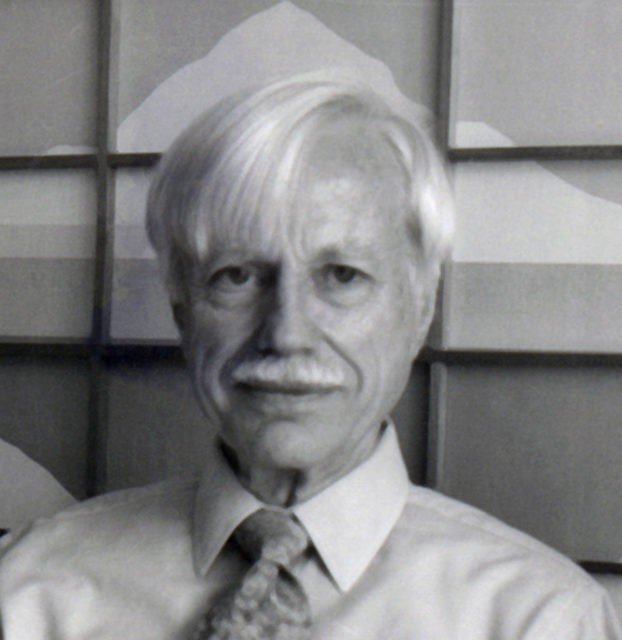

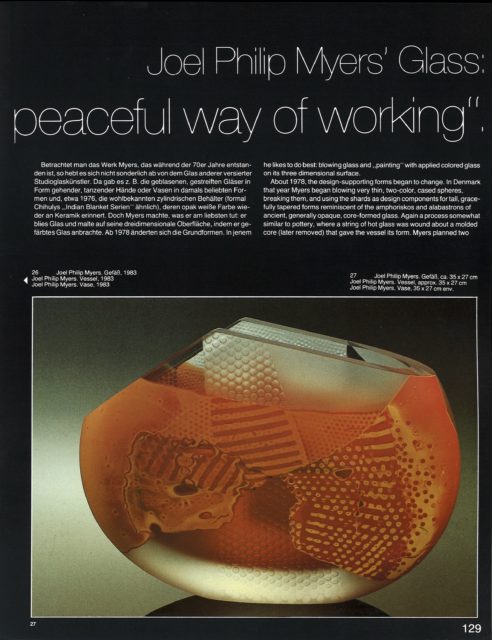

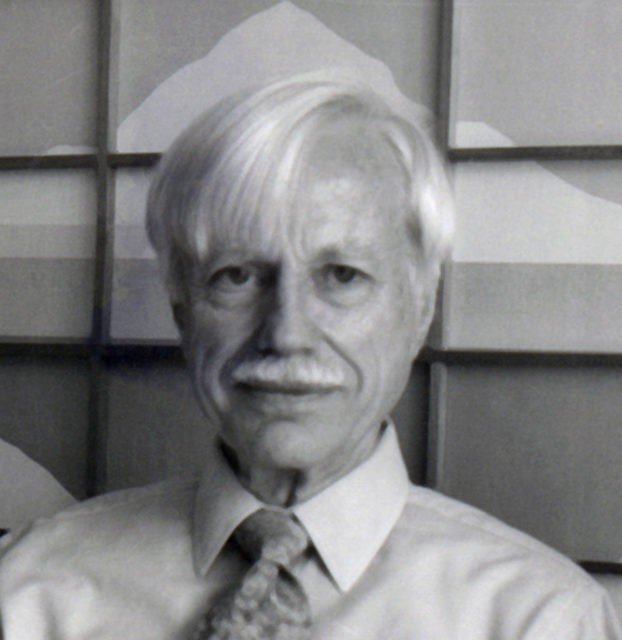

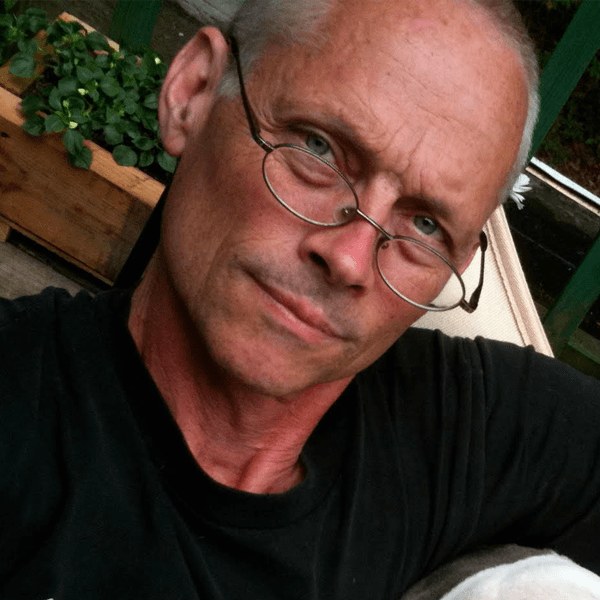

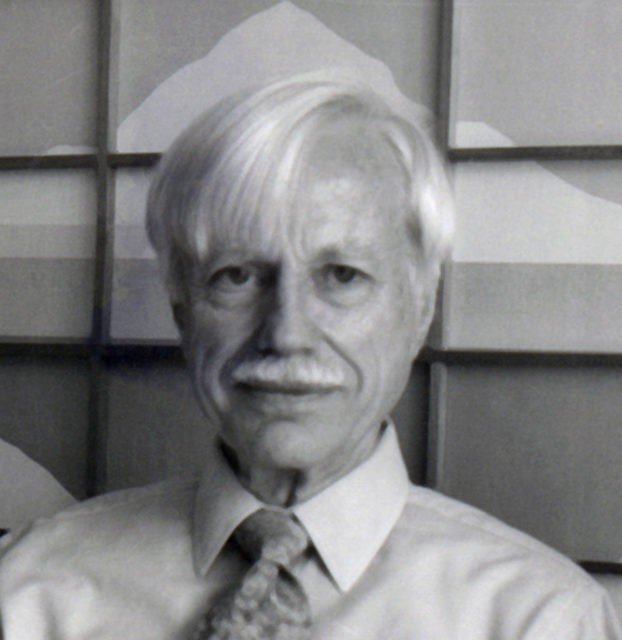

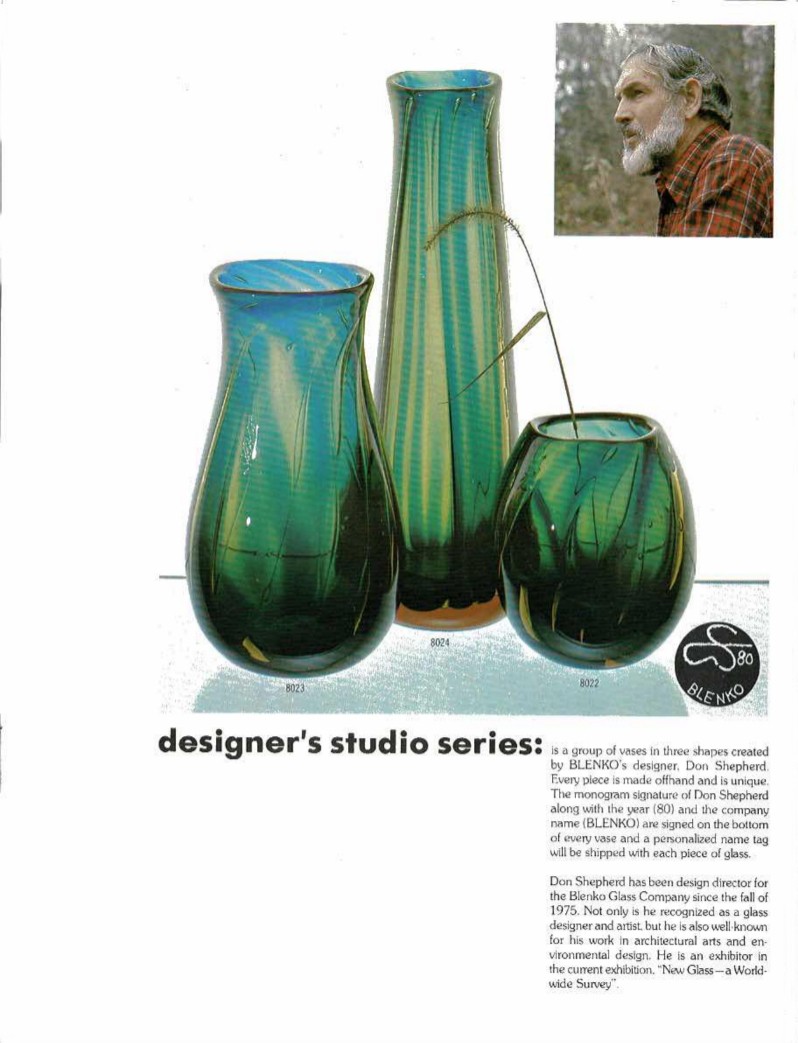

Blenko’s designers have been vital to the company. The first, Winslow Anderson, was hired in 1947. Blenko’s employment of in-house design directors resulted in modern product lines that often featured lively and unusual shapes that attracted critical attention. Several of Anderson’s designs, such as his bent-necked No. 948 Decanter, were showcased in Good Design exhibitions organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art between 1950 and 1955. Anderson’s successor, Wayne Husted (director 1953–1963), created some of Blenko’s most celebrated and recognized items; the influential survey Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass, organized by The Corning Museum of Glass, included a Husted-designed bud vase with a distinctive bifurcated top. Joel Philip Myers (dir. 1963–1970) was the first in a succession of studio glass artists to become a designer director, followed by John Nickerson (dir. 1970–1974), Don Shepherd (dir. 1974–1988), and Hank Murta Adams (dir. 1988–1994). Myers learned the intricacies of glassblowing while working at Blenko, while Adams was one of the last students at RISD to train under Dale Chihuly. Later design directors included Matt Carter and Arlon Bayliss.

No. 948 Decanter in emerald green with bent neck and button stopper, designed by Winslow Anderson, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1950. The decanter was recognized with a Good Design Award by the Museum of Modern Art. Rough pontil. Overall H: 13 in. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2010.186.5a-b).

Vase, blue and clear, designed by Wayne Husted, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1959, Overall H: 15.625 in. In Glass 1959: A Special Exhibition of International Contemporary Glass, The Corning Museum of Glass, p. 303.

Image Courtesy of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

No. 6516 Decanter with elaborate stopper in turquoise, designed by Joel Philip Myers c. 1965, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1965-1977, Overall H: 14.5 in. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2011.57.4a-b).

No. 6511 Pitcher in tangerine, designed by Joel Philip Myers c. 1965, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1965-1978. Optic, hand applied handle, pontil, Overall H: 9.25 in. Collection of the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia. (2011.117.13).

1965 Blenko catalog featuring glassware designed by Joel Philip Myers (far left and far right) and Wayne Husted (four in center). In Leslie Peña, Blenko Glass 1962-1971 Catalogs, p. 12 (Schiffer Books Publishing Ltd., © 2000), p. 58.

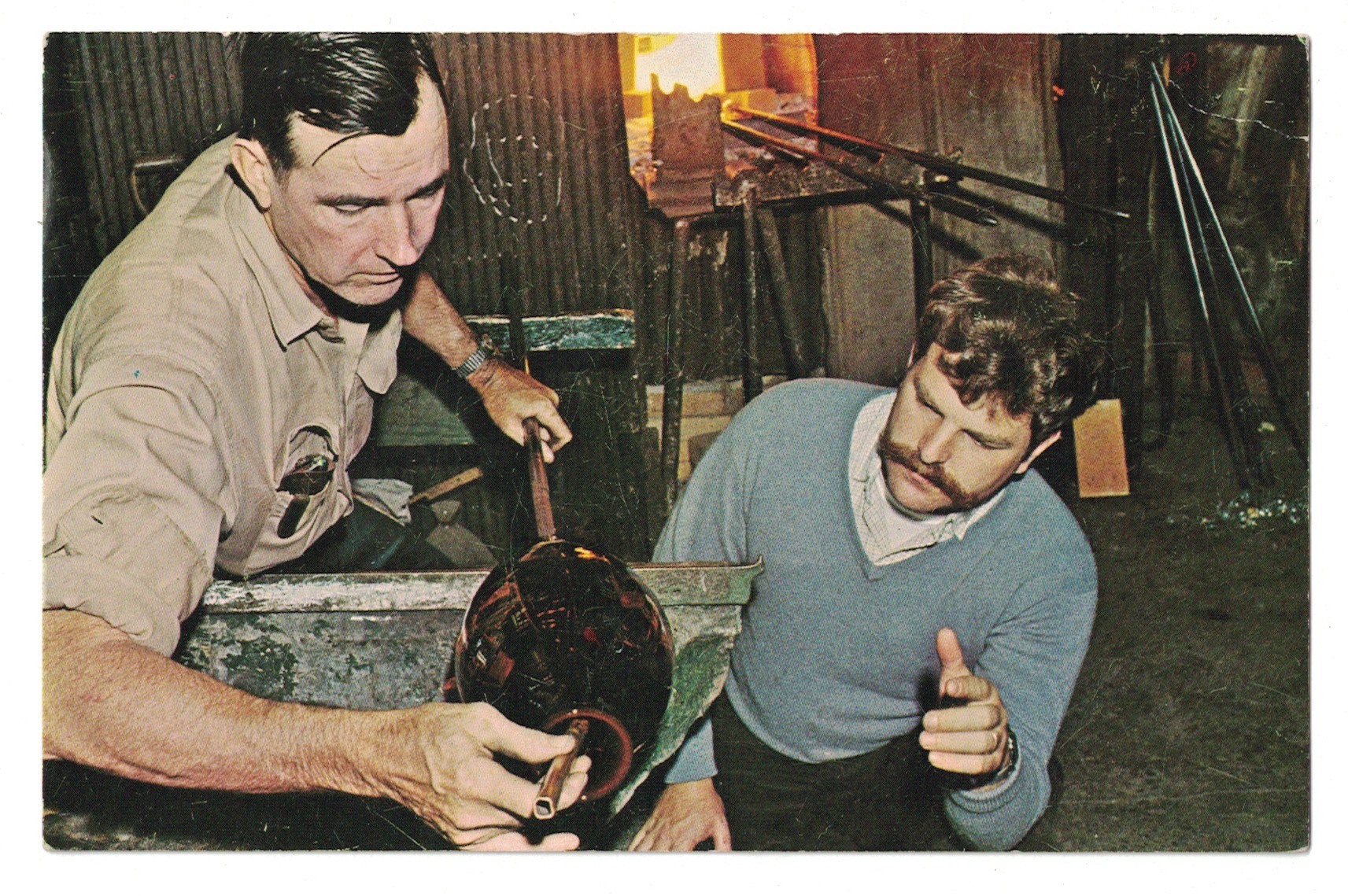

Finisher Connie Blake (left) with Joel Philip Myers. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“I was offered the position of design director at Blenko Glass in 1963 just as Littleton was trying to sell the idea of individual artists working with glass creatively, and as a start, within the confines of the university art department. I signed on with Blenko with the absolute intention of learning how to blow glass, although I was hired to design the Blenko line of glassware….I had a fantastic position with great creative freedom and an open door to pursue my self development in the technique of glassblowing; Mr. Blenko Sr. and Jr. generously supported me throughout my seven-year tenure….since the movement was in its infancy they—and I myself—could never have foreseen the global spread of the movement.”

“First time I saw [Joel Philip Myers’s] work was at the Philadelphia Convention Center at some kind of an exhibition, and I was astonished that he could have those colors available to him. And Blenko had a great range of colors, and he could just go out and blow glass with seven different colors—all on the same day and stick them all together on one piece. I mean, his pieces were very colorful and compelling to me because of that.”

In a 1983 interview with Paul Hollister Joel Philip Myers discusses the use of glue in his pieces, being of the older generation of glass artists, preconceived notions in glassmaking and positivity in his work.

“Joel Philip Myers’ Glas: Eine ruhige, friedvolle Art zu arbeiten / Joel Philip Myers’ Glass: ‘A Quiet, Peaceful Way of Working’.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (July/September 1983): 128–133.

Hank Murta Adams talks about Blenko’s lamps and stoppered bottles and their popularity in the 1950s.

Display of Blenko glassware, c. 1950s or 1960s. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Artists at Blenko

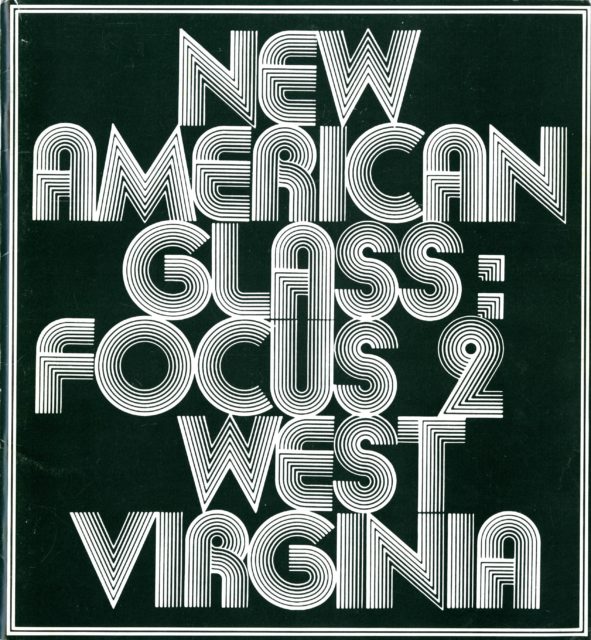

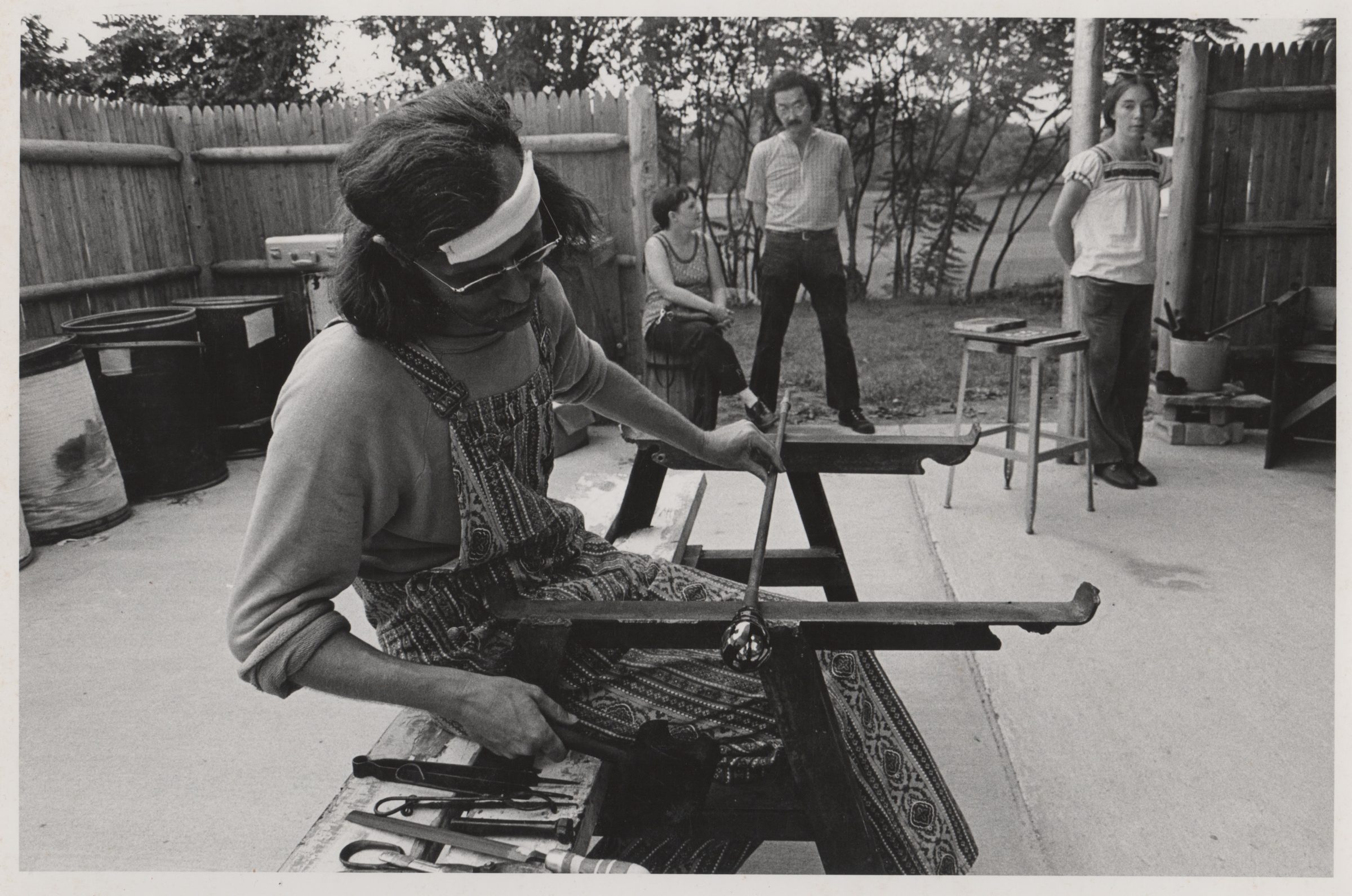

Blenko has a long history of allowing artists to use its facilities. Prior to the early 1970s, many studio glass artists had never been inside a factory. In 1973 and 1974, however, the Glass Art Society (GAS) held its annual conference in Williamstown, West Virginia. Through these conferences, organized by Henry Halem and hosted by Frank Fenton of Fenton Glass Works, attendees became aware of local glass firms. Two years later, the Huntington Galleries (later the Huntington Museum of Art) took part in New American Glass: Focus West Virginia, a project funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which brought six glass artists to West Virginia to create prototype designs in local factories. Resulting pieces became part of the Huntington’s permanent collection. Joel Philip Myers nominated glass artist Fritz Dreisbach to work at Blenko for the project. A decade later, Paul Hollister wrote the catalogue essay for the Huntington’s follow-up national invitational survey, New American Glass: Focus 2 West Virginia (1986), plus a stand-alone critique of the exhibition.

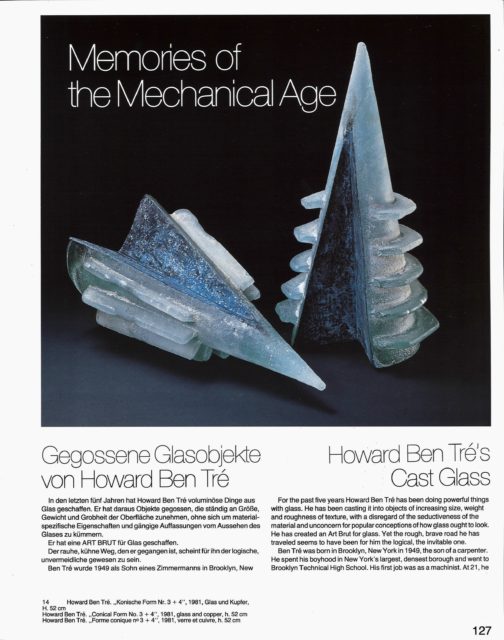

Other glass artists who came to Blenko included Howard Ben Tré, Marvin Lipofsky, and Jim Harmon; Hollister wrote about the cast pieces that Ben Tré made in articles for the New York Times and Neues Glas. Blenko’s designers also created their own work at the factory. Hank Murta Adams, through former Blenko designer Don Shepherd, became part-owner of an annealing oven set up by Ben Tré, enabling Adams to produce cast objects before, during, and after his tenure.

Oven set up by Howard Ben Tré at Blenko, 1981. Image courtesy Wendy MacGaw.

Howard Ben Tré using his specially-made oven at Blenko, 1981. Image courtesy of Wendy MacGaw.

Don Shepherd discusses Howard Ben Tré setting up an annealing oven at Blenko in a 1981 interview.

New American Glass: Focus 2 West Virginia. Huntington, WV: Huntington Galleries, 1986. Includes Hollister’s marginalia and the insert “Critique.”

“Memories of the Mechanical Age: Gegossene Glasobjekte von Howard Ben Tré / Howard Ben Tré’s Cast Glass.” Neues Glas, no. 3 (1982): 127–33.

Producing Glass

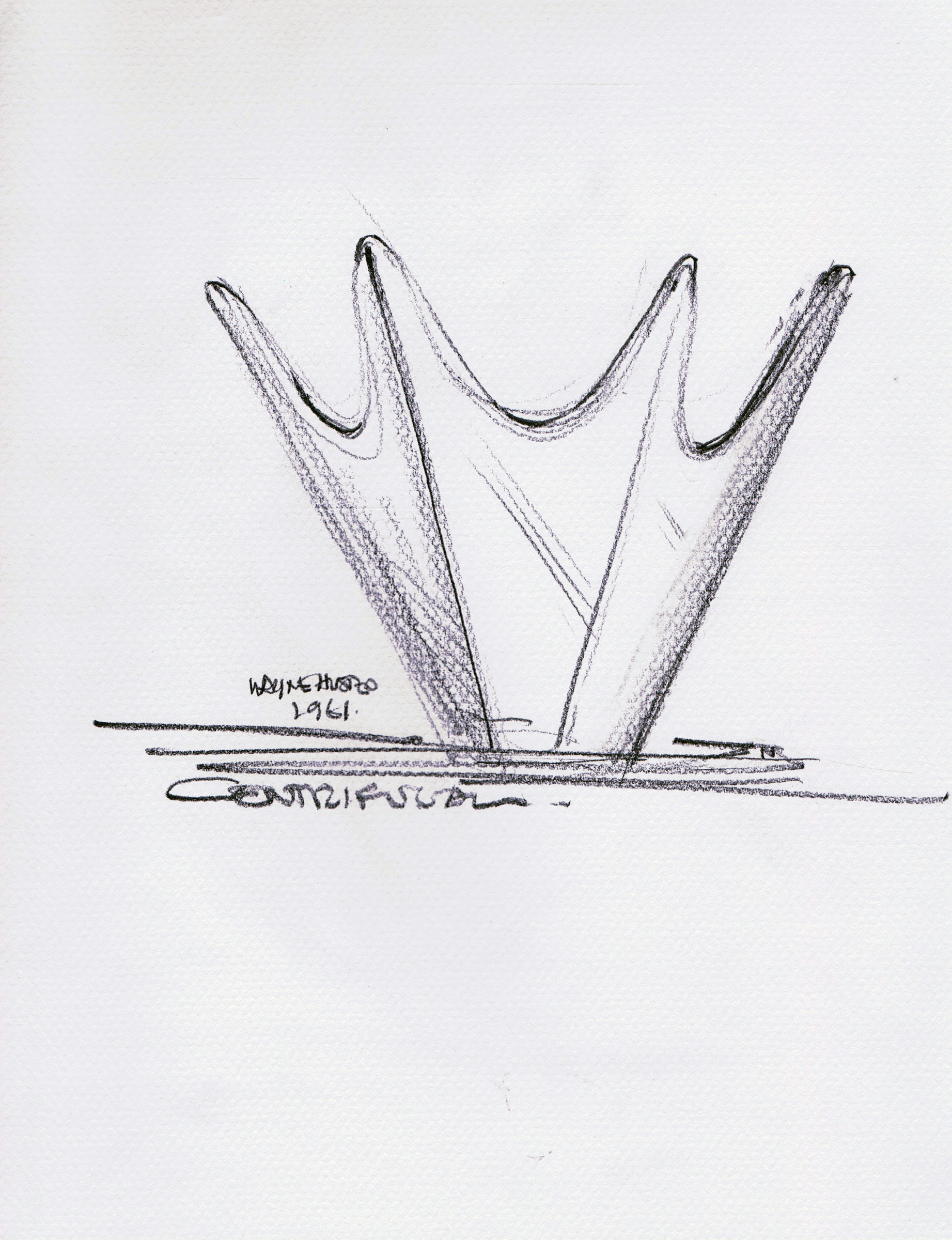

While many different techniques have been employed at Blenko, the company is particularly well known for the use of molds in its production process. Hand-carved cherrywood molds, for example, are employed to shape its blown tableware. About 80 percent of Blenko’s production has utilized wooden turn molds. These molds enable makers to rotate the blowpipe so that the glass does not stick to the sides of the wood, which can mark it. Wooden molds, while considerably less expensive to create than metal ones, wear out after fifty to a hundred uses. More durable, cast iron molds are used for objects made in large quantities, such as Blenko’s signature water bottle, in continuous production since 1938. “Dump” molds—into which hot glass is literally dumped and allowed to solidify before being removed—are ideal for smaller items that can be made quickly, such as paperweights, bookends, and animal figurines. Centrifugal “spin” molds, invented by Husted in 1961, are for objects like flower petal bowls and ashtrays. Based on a potter’s wheel, these open-faced molds sit on a fast-moving turntable; centrifugal force pushes the glass up the side of the mold to form the object.

Original drawing of a Blenko vase, entitled “Centrifugal” and signed “Wayne Husted 1961.” Collection of the American Museum of Glass, Weston, West Virginia. (2017.2.61).

No. 6143S Salad Bowl in Kiwi, designed by Wayne Husted c. 1961, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, c. 1998-2004. H: 3 in, Diam: 5.375 in. Collection of the American Museum of Glass, Weston, West Virginia. (2012.84.1).

“I’ve spent an immense amount of time in all kinds of American glass factories. And I don’t know anybody else that has their main line of product produced in hand-carved molds.”

Daniel Chapman chiseling a cherrywood mold. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blowing into a mold. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“The reason wood molds are used comes down to cost. You can prototype designs a lot faster and cheaper by using a wood mold. If that design proves to be a success, then you invest in a metal mold….while Blenko does use some metal molds, graphite, and aluminum, historically Blenko have used wood. And I think that is one reason why they still do it. It is true to the process and while not unique to Blenko it is part of what makes Blenko, Blenko.”

Don Shepherd talks about being a designer for Blenko and making a mold made out of coat hangers in a 1981 interview with Paul Hollister.

“Water bottle molds are iron. We’d have to have a new hand-carved mold every two days because of the volume we’ve produced in that item.”

384 Water Bottle, Blenko Glass Company, 2019. In limited edition “gold rush” color, Overall H: 8 in. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“Usually one piece at Blenko takes—depending on how complicated—maybe five to eight minutes per piece. You know, certain designs, you can get a lot more, cause there’s less bit work, or additions, certain designs you can do faster or take longer, because of the additional work. But they can make between 20 to 30 pieces an hour, depending on the design. A water bottle is different because it’s a pretty straightforward piece, you know, they just blow it. Then there’s a process where they do an overblow, or it gets really, really thin. They put it in a clamp instead of a punty. They roll it, melt the lip and then finish the spouts and then you’re done. So it’s maybe a minute per bottle versus six minutes.”

Blenko Tableware. Shipping Building, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Bin with soaking wooden molds, featuring glassblowers Everett “Shorty” Finley (in white) Dave Osburn (red t-shirt), Blenko designer Matt Carter (plaid shirt), and Kent State student (in purple). Excerpt from “Kent State University Students at Blenko Glass, Milton, West Virginia, 1994,” video by Henry Halem. Courtesy of Henry Halem.

“Blenko tends to get cherrywood/fruit wood from local farmers that are around Milton—or it did when I was there. It is a soft wood which is good for carving the initial design. But it also will soak up the water better than other woods. The water is key for a couple of reasons: one it keeps the mold from burning up faster, and second, it creates a layer of steam that is formed between the glass and the wood. This helps shape the piece as well as helps give it a nice smooth finish….when done they place it back into water until the next piece. Wood molds do burn out over time and they will need to be replaced…over time you will see the shape change. If you compare a piece that was made in a new mold versus an older one, you can definitely see the difference between the two.”

Blenko’s Glassmakers

Glassblower Everett “Shorty” Finley in an undated photo at Blenko. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

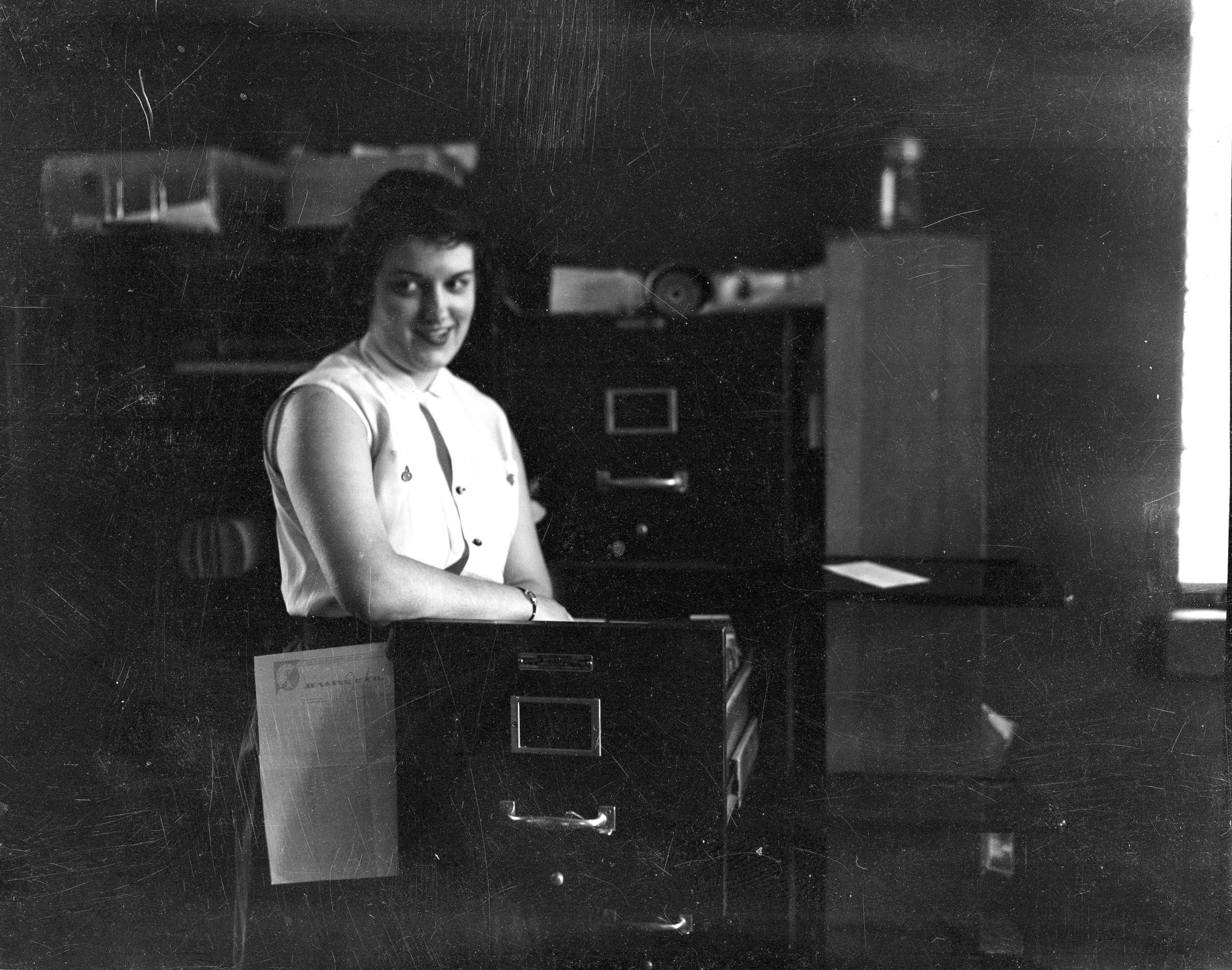

Office worker at Blenko, c. 1950s or 1960s. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Glassmaking at a factory is difficult work with long hours. At Blenko, days typically start at six in the morning, with shifts split between tableware—the main product line—and “antique,” which includes handblown and flattened sheet glass known as “dalle de verre” as well as dump-molded pieces and spinware. As of 2020, all of Blenko’s glassworkers have been men, although women have been employed for other jobs, often as packers or administrators. Glassmakers go through an extended apprentice system and then choose whether they would like to be blowers or finishers. Many have had nicknames. The late Everrett “Shorty” Finley was an expert blower who was photographed repeatedly by the company. Hinton “Jarfly” Richmond (1926–2004) was a greatly respected foreman who worked at Blenko for almost fifty years before retiring.

As design director, Hank Murta Adams pushed for glassworkers’ benefits, including holiday bonuses. He also strove to improve company morale so that workers felt valued, appreciated, and motivated.

“I had to make them appreciate what they had, and the results came back. But it wasn’t money that I was solely interested in, I was interested in the work….I actually grew to love the work and the results, and I was doing all of this while I was still having three one-man shows of my own sculpture a year, so I was—in retrospect, I don’t know how the hell I did it, but I did it.”

Antique Office, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 2020. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Everett “Shorty” Finley (in white) blowing glass at Blenko with Dave Osburn (red t-shirt). Excerpt from “Kent State University Students at Blenko Glass, Milton, West Virginia, 1994,” video by Henry Halem. Courtesy of Henry Halem.

Blenko Glassworkers. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“When I was there, there were seven ‘shops’ and each shop is a team of usually five to six workers. And they’re responsible for making the glass. So there’s a finisher, there’s a blower. There’s a gatherer. There’s a ‘bit boy’. And there’s a ‘carry-in boy’. That’s five. And sometimes there’s a mold guy who opens and closes the molds and sometimes they overlap duties, the finisher and the blower are the main guys of the crew and everyone else serves them.”

Glass Recycling

Cullet Bins, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Cullet Bins, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

In a glass factory, flawed or damaged products as well as waste glass from cooled melts are often broken or crushed into small pieces of scrap called cullet, which can then be recycled as an ingredient in new batches of molten glass. Paul Hollister took many photographs of Blenko’s cullet.

Cullet must be carefully sorted to ensure compatibility of the materials combined in the glassmaking process; eventually, most companies accumulate a surplus. American manufacturers have sometimes given their unused material to schools and universities, a welcome replacement for the low-quality bottle or green glass that many programs have relied upon. Artists who worked in factories also facilitated donations. Blenko designer Joel Philip Myers, for example, sent barrels of cullet to studio glass artist Richard Ritter for his classes at the Bloomfield Art Association in Michigan. Paperweight maker Randall Grubb, an equipment builder for Correia Art Glass in the early 1980s, donated high-quality colored cullet from the company to the University of Southern California, where he was enrolled.

As the glass industry has declined, obtaining cullet has become more difficult. One important resource has been Gabbert Cullet, a small company founded in Williamstown, West Virginia, by O. J. Gabbert, who gathered material from various factories and resold it. Many studio glass artists, including Henry Halem, Fritz Dreisbach, and Blenko designers Myers and Adams, purchased from the company. Southwestern glass artist Flo Perkins also used cullet from Gabbert, which she learned about from Richard Marquis, her instructor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Joel Philip Myers talks about O. J. Gabbert’s cullet in a 1983 interview with Paul Hollister.

01:19 Transcript

Richard Ritter glassblowing at Bloomfield Art Association, with barrels of Blenko’s cullet (left background) from Joel Philip Myers, 1971. Image courtesy of Richard Ritter. Photo by Robert Vigiletti.

“In 1971, the Bloomfield Art Association established a National Glass Show, one of the first nationwide glass exhibitions in the United States. We invited Harvey Littleton to come to the BAA and jury the show with me. During his visit, we discussed options for a better source for glass to melt in our furnace, and he suggested I call Joel Myers, who had been a designer at Blenko for several years….[Myers] was extremely helpful and told me that he would ship up some glass for us to try. A few weeks later…a huge semi-truck pulled up that was full of barrels of glass cullet from Blenko, all different colors. It was just fantastic….what a difference the glass from Blenko made in my work, and in the work of my students! Blenko’s colors were beautiful, and the glass much more suited to blowing than our bottle glass.”

Toots Zynsky talks about Blenko donating cullet and allowing artists to use their facilities.

0:19 Transcript

Randall Grubb describes providing the University of Southern California with high-quality glass from Correa.

02:16 Transcript

Cullet Bins, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Cullet Bins, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“But the point is that color being given to universities from factories like Blenko was a great gift because you weren’t going to get color. It was a real treat.”

Cullet Heaps, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Slag Heap, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Cullet Heaps, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Detail of Cullet, Blenko Glass Company, Milton, West Virginia, 1986. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

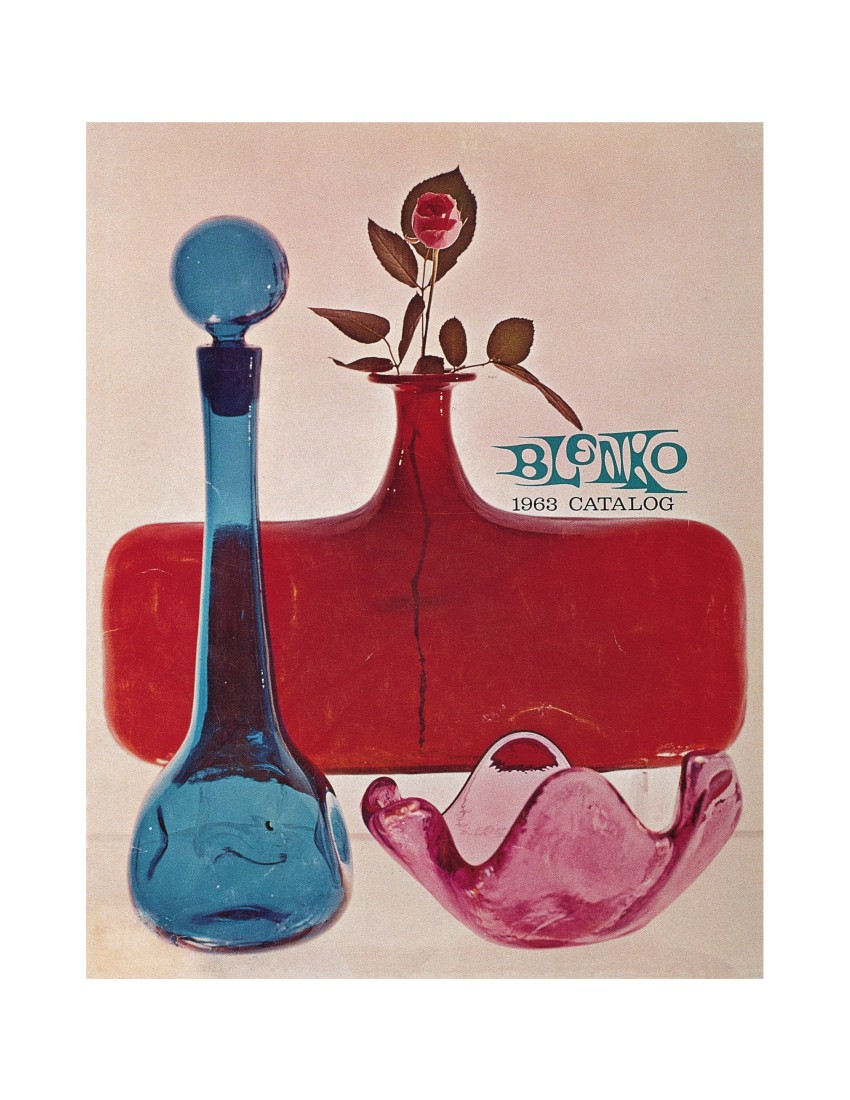

The Blenko Catalog

Cover. Blenko Catalog, 1963. In Leslie Peña, Blenko Glass 1962-1971 Catalogs (Schiffer Books Publishing Ltd., © 2000), p. 18.

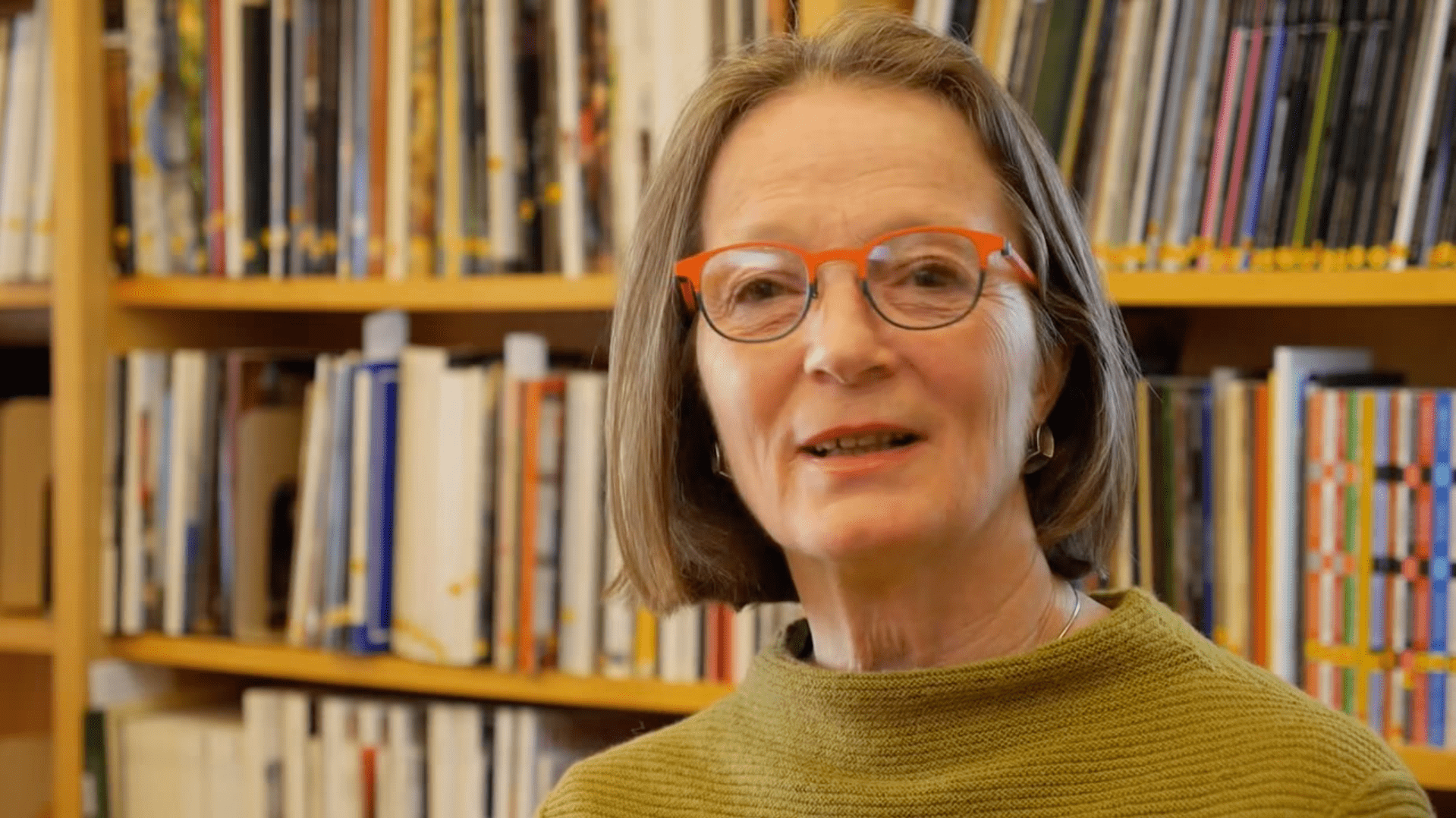

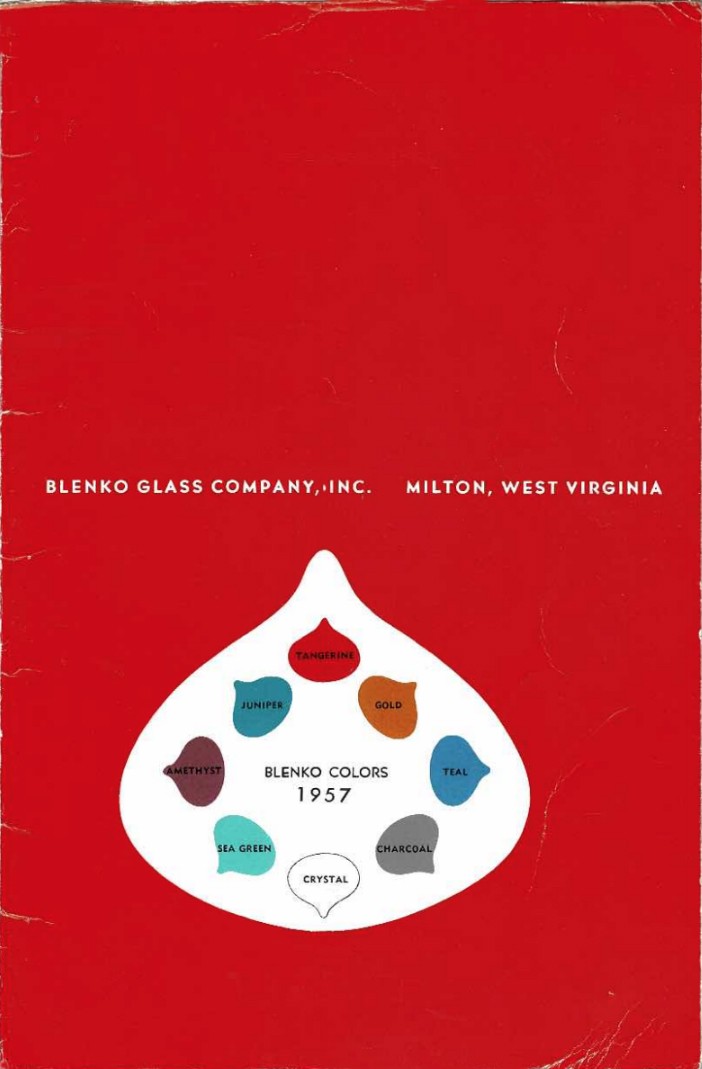

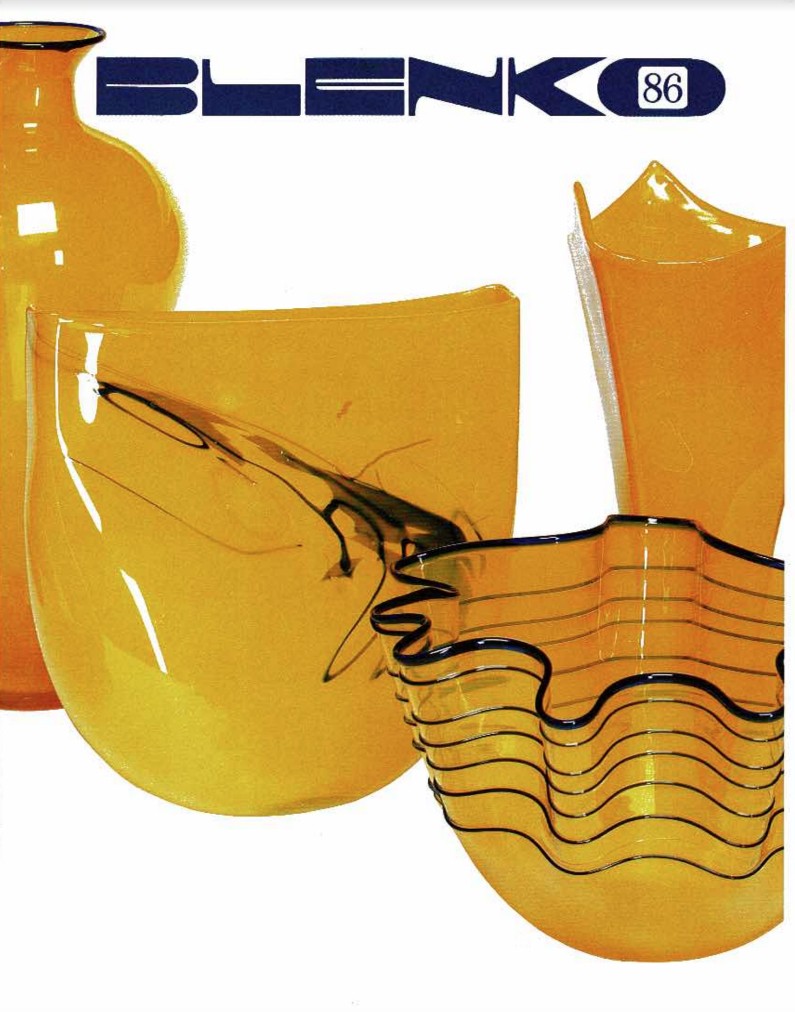

Since the mid-1930s, Blenko has showcased its product line in an annual catalog. As the company has introduced new hues and phased out others, each publication has featured a page showing available colors, often evocatively named. During the early 1960s, palettes included turquoise, amethyst, tangerine, sea green, jonquil, crystal, and rosé. Later in the decade, chestnut, honey, peacock, plum, lemon, and wheat appeared. Collectors, dealers, and curators alike have sought out past catalogs to help identify and authenticate Blenko glass objects. Early examples were printed in black and white, but in 1959, under the direction of Wayne Husted, Blenko issued its first color catalog. Until the advent of digital technology, photographers shot the necessary images on film using long exposures. Color mistakes due to off-shade samples would warrant trips back and forth to the plant. Although catalogs typically have not highlighted designers beyond mentioning their names, the 1980 issue featured a full page on Don Shepherd, noting his inclusion in the prestigious 1979 exhibition New Glass: A Worldwide Survey, organized by The Corning Museum of Glass. During the tenure of design director Hank Murta Adams, a vocal advocate for worker recognition, catalogs began including glassmakers’ names and often their roles.

Available colors in 1957, Blenko Catalog, 1957. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“I have, I think, every catalog from the forties up in my office in New York…I was so smitten, and so engaged…I wasn’t a design major. I was horrible at graphics. I mean I’m [laughs] kind of an expressionistic painter, but I was responsible for all aspects of that in the company. So I spent every Thanksgiving up in Marietta, Ohio, and Williamstown [West Virginia] where their publisher was—they’d used the same publisher for 30 years, and I’d spend every Thanksgiving up there with the line…and if you have seen a Blenko catalog you know that the first page is the color page and every year they’d present the new color. And that was fun because I would get to design the color and get to utilize it.”

Cover. Blenko Catalog, 1986. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blenko Catalog, 1980 issue featuring Don Shepherd. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Cover. Blenko Catalog, 1960. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Cover. Blenko Catalog, 1960. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blenko: 21st Century

In its fourth generation of family leadership, Blenko has continued to produce new forms and roll out new hues. In 2017, the company hired its first woman designer, Emma Walters, as codirector of design with Andrew Shaffer. Contemporary collectors, prizing historic designs and colors, have fostered an active secondary market for Blenko glass. As other West Virginia glass factories have closed, the company has continued its participation in heritage tourism to raise its visibility and promote sales. It offers factory tours and has an observation area for watching craftspeople at work, a Visitor Center with historical exhibits and a shop, and an outdoor garden decorated with Blenko-produced objects and glass panels made by Joel Philip Myers.

Grinding shop, Blenko. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

“Not only is the design world changing, and the products changing, and the sales mechanisms changing, but guess what? What we keep going back to is the human element—the people that are actually doing the work—and it’s not robot work. It’s not mechanization. It’s variability and it’s striving and the reason that handcraft is so important is because it’s imperfection. It’s striving that comes through it. It’s the striving that makes it human, that makes it creative, and makes it valuable. And that’s what people don’t understand about digital work.”

Emma Walters designing for Blenko. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blenko 384 water bottles. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Glassblowing classes, Blenko. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.

Blenko’s Visitor Center. Image courtesy of Blenko Glass Company.