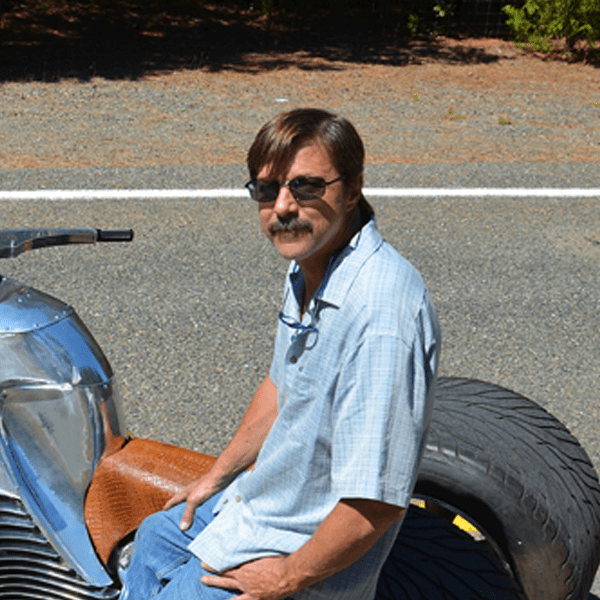

Image courtesy of Randall Grubb.

Randall Grubb

Artist Randall Grubb (1961– ) discovered glassblowing while an undergraduate at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He became interested in paperweights and flameworking techniques while working with paperweight maker Chris Buzzini at Correia Art Glass in nearby Santa Monica, California, where Grubb was employed as an equipment builder while still in college. In the mid-1980s, Grubb moved to Oregon and began making glass paperweights in his own studio. After twenty successful years as a paperweight artist, Grubb began to combine his artistic experience with his lifelong interest in metalworking and love of hot rods. He currently designs and builds specialty collector cars from the ground up.

Works

Octopuses Garden, 1997. Glass. Image courtesy of Randall Grubb.

Daisy, 1997. Glass. Image courtesy of Randall Grubb.

Falconer Dodici, 2016. Image courtesy of Randall Grubb.

Randall Grubb talks about the importance of industry supplying glass formulated for glassblowing to universities.

1:06 TranscriptRandall Grubb talks about how he and Chris Buzzini had been attempting to make paperweights on their own.

02:06 TranscriptRandall Grubb talks about how tiny Paul Stankard’s flameworked elements actually are.

00:54 TranscriptRandall Grubb describes providing the University of Southern California with high-quality glass from Correa.

02:16 Transcript