*Tools of the Trade*

*Tools of the Trade*

arving tools were both functional and symbolic; their precious materials and iconography added drama and elegance to a meal. Surviving cutlery from the early modern period is challenging to assign to a particular country or region. Most collections skew toward objects of outstanding craftsmanship, selecting for items made of costly luxury materials such as gold, silver, ivory, or mother-of-pearl. Carving sets of companion knives and forks are sometimes difficult to distinguish from smaller personal utensils since sizing was not standardized. Personal forks were not routinely used until the seventeenth century in most of Europe, with Italians leading the trend.

arving tools were both functional and symbolic; their precious materials and iconography added drama and elegance to a meal. Surviving cutlery from the early modern period is challenging to assign to a particular country or region. Most collections skew toward objects of outstanding craftsmanship, selecting for items made of costly luxury materials such as gold, silver, ivory, or mother-of-pearl. Carving sets of companion knives and forks are sometimes difficult to distinguish from smaller personal utensils since sizing was not standardized. Personal forks were not routinely used until the seventeenth century in most of Europe, with Italians leading the trend.

Utensil sets designed specifically for carving often feature forks with two long tines, designed to spear the food securely so that it could be carved while held aloft for maximum theatrical effect. Knife blades, generally of steel, sometimes feature makers’ marks, but years of sharpening and polishing have worn these marks down and they are often hard to identify.

Above: Carving knife and fork, Southern Germany, 19th century. Steel and buckhorn. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of R. Stuyvesant, 1893, 93.13.5,6.

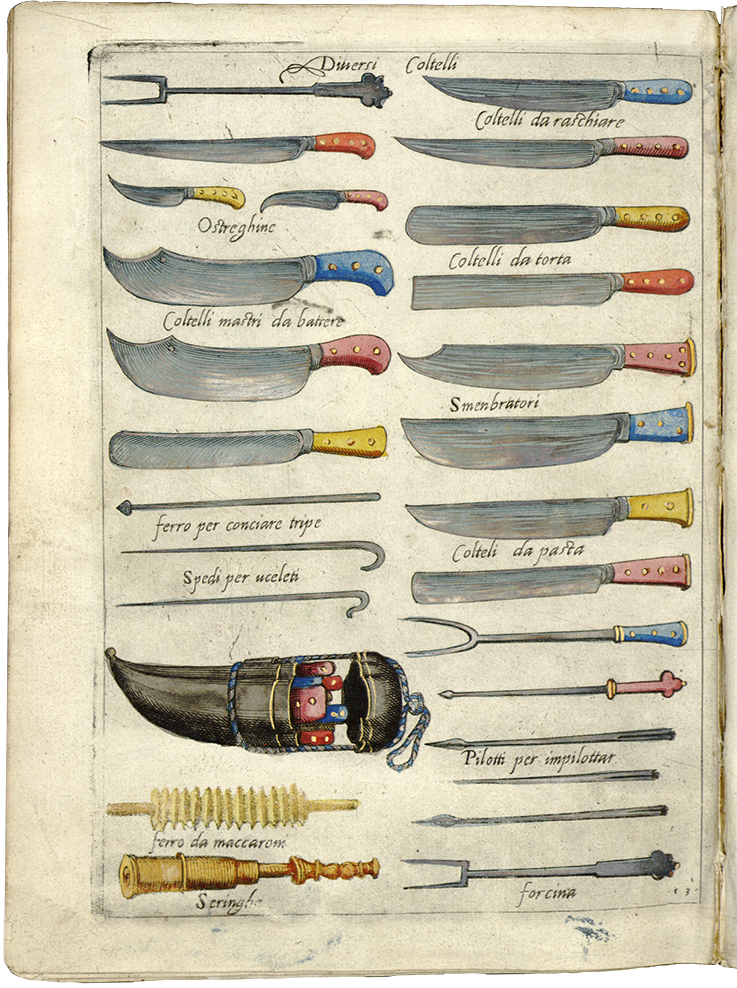

*A Sharper Edge* One of four illustrations of kitchen interiors in Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera, this woodcut depicts various functional elements, including a basin for dishes waiting to be washed, a large wooden tub for live fish, and a well. Against the back wall is a large foot-powered wheel for sharpening knives, labeled Rotatore. Knives of different sizes, perhaps awaiting their turn at the wheel, are laid out on a work table at the front of the room. Similar tools are also catalogued on the page titled “Diversi coltelli” from the same book, displayed together.

*A Sharper Edge* One of four illustrations of kitchen interiors in Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera, this woodcut depicts various functional elements, including a basin for dishes waiting to be washed, a large wooden tub for live fish, and a well. Against the back wall is a large foot-powered wheel for sharpening knives, labeled Rotatore. Knives of different sizes, perhaps awaiting their turn at the wheel, are laid out on a work table at the front of the room. Similar tools are also catalogued on the page titled “Diversi coltelli” from the same book, displayed together.

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Loggia,” from Opera . . . (Venice: V. Pelagalo, 1596). Woodcut. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB.

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Loggia” and “Diversi coltelli,” from Opera . . . (Venice: V. Pelagalo, 1596). Woodcut. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB.

The beautiful hand coloring in this unique copy of the first edition of Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera suggests that the illustrations were perceived as more than a visual shopping list for setting up a proper kitchen. They might be compared to still-life paintings depicting kitchen utensils that were popular in seventeenth-century Europe. Before printing in full color was widely available, many book illustrations were hand-colored by specially trained artists. This copy was colored sometime before it entered the Göttingen library in the eighteenth century.

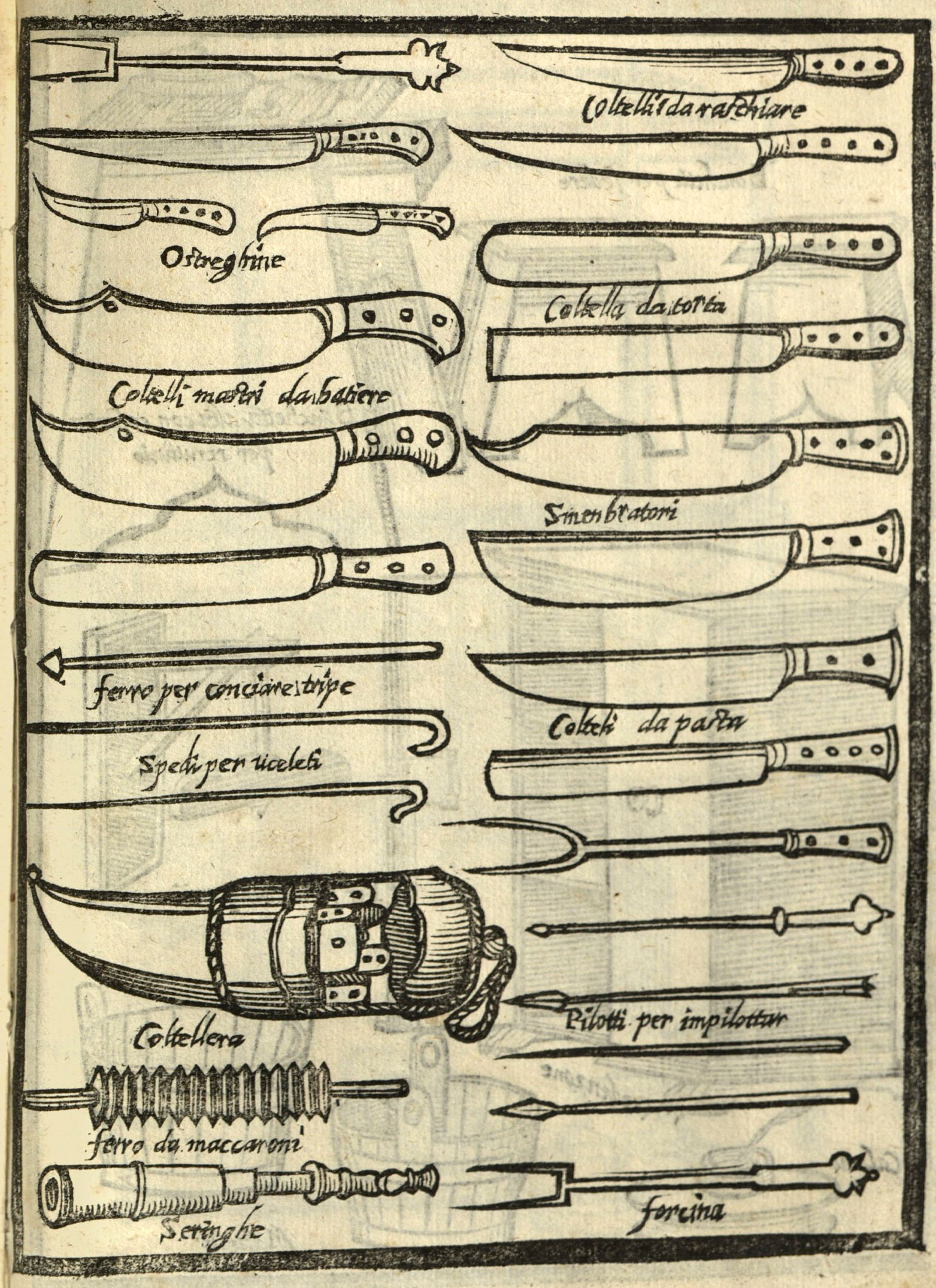

A later edition of Scappi’s cookbook replaced the original copper-plate engravings with woodcuts, which were cheaper to create, as seen above in the same image of knives and other sharp implements.

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Diversi Coltelli,” from Opera . . . , plate 13 (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1570). Hand-colored engraving. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Manuscripts and Rare Prints/University Archives 8 OEC I, 3660 RARA.

The beautiful hand coloring in this unique copy of the first edition of Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera suggests that the illustrations were perceived as more than a visual shopping list for setting up a proper kitchen. They might be compared to still-life paintings depicting kitchen utensils that were popular in seventeenth-century Europe. Before printing in full color was widely available, many book illustrations were hand-colored by specially trained artists. This copy was colored sometime before it entered the Göttingen library in the eighteenth century.

A later edition of Scappi’s cookbook replaced the original copper-plate engravings with woodcuts, which were cheaper to create, as seen above in the same image of knives and other sharp implements.

Left: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Diversi Coltelli,” from Opera . . . , plate 13 (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1570). Hand-colored engraving. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Manuscripts and Rare Prints/University Archives 8 OEC I, 3660 RARA.

These are modern replicas of the kitchen knives illustrated in Bartolomeo Scappi’s influential recipe book. Instructions found in many of the carving manuals recommend they be kept scrupulously clean and lethally sharpened. Each knife had different functions as the labels reveal: ostreghine for opening oysters; smembratori for dismembering; coltella da torta for cutting cakes; and coltelli da pasta for shaping pasta dough. Such advanced equipment required skilled artisans to make it and highly trained staff to use it.

These are modern replicas of the kitchen knives illustrated in Bartolomeo Scappi’s influential recipe book. Instructions found in many of the carving manuals recommend they be kept scrupulously clean and lethally sharpened. Each knife had different functions as the labels reveal: ostreghine for opening oysters; smembratori for dismembering; coltella da torta for cutting cakes; and coltelli da pasta for shaping pasta dough. Such advanced equipment required skilled artisans to make it and highly trained staff to use it.

*Carving Sets* Alternating bands of horn and bone form the lower portion of the handles of this imposing knife and fork, likely made for carving at the table or on the hunt. Broad brass bolsters border punched brass panels on the hilt. Steel rivets fasten the tang, which extends fully into the butt. The curved shape of the fork is very distinctive, recalling antlers or horns.

*Carving Sets* Alternating bands of horn and bone form the lower portion of the handles of this imposing knife and fork, likely made for carving at the table or on the hunt. Broad brass bolsters border punched brass panels on the hilt. Steel rivets fasten the tang, which extends fully into the butt. The curved shape of the fork is very distinctive, recalling antlers or horns.

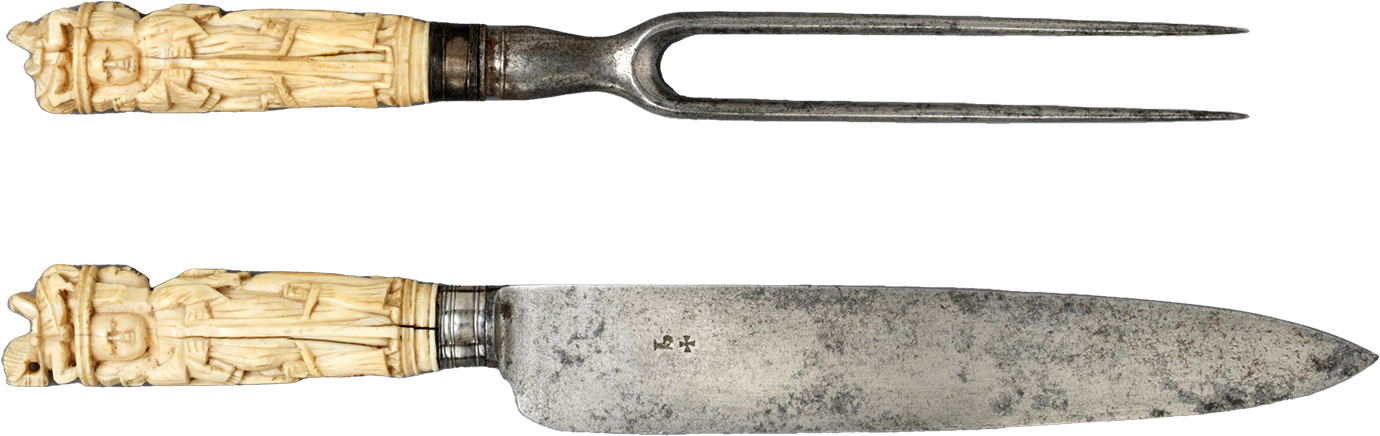

The handles on both fork and knife feature high relief figures of walrus ivory representing Faith, holding scales; Hope, with an anchor; and Charity, with a cross and children at her feet. Kneeling horses, their riders broken off, crown both implements, suggest- ing chivalric themes. Both fork and knife are forged of sturdy steel with a silver collar marking the transition from handle to blade. Related pairs have different top elements, with lions or human heads, suggesting a common workshop.

Above: Carving knife and fork, Netherlands, possibly Friesland, Late 17th–early 18th century. Steel, walrus ivory, and silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of R. Stuyvesant, 1893, 93.13.91, 92.

The handles on both fork and knife feature high relief figures of walrus ivory representing Faith, holding scales; Hope, with an anchor; and Charity, with a cross and children at her feet. Kneeling horses, their riders broken off, crown both implements, suggest- ing chivalric themes. Both fork and knife are forged of sturdy steel with a silver collar marking the transition from handle to blade. Related pairs have different top elements, with lions or human heads, suggesting a common workshop.

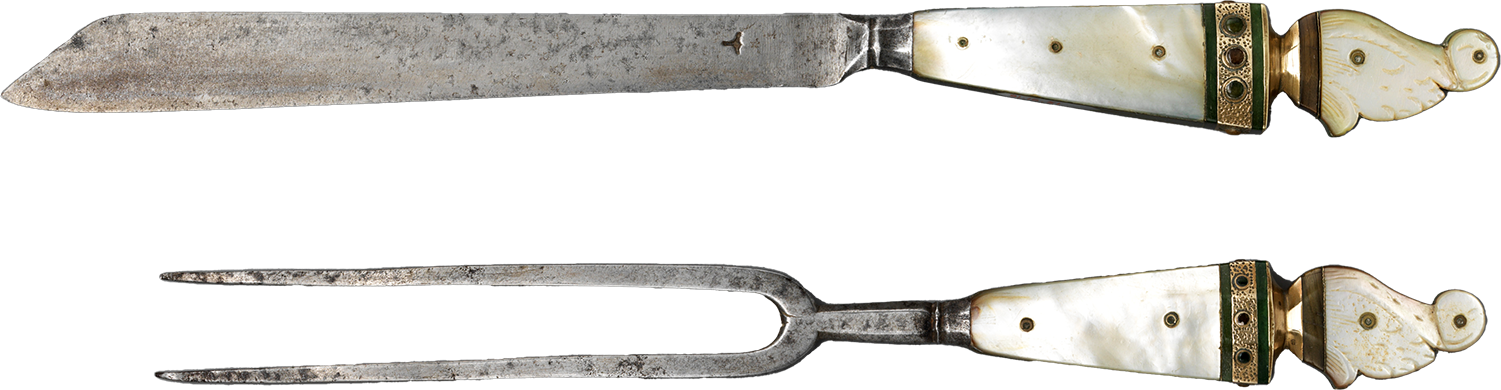

This knife and fork are probably examples of Haban wares, made by Hutterites, a sect of Anabaptists who moved as a group between Germany, Austria, and Moravia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Although they practiced an ascetic lifestyle, cutlery, ceramics, shoes, and clocks crafted by the Hutterites in collective settings were highly regarded for their skill and quality. The utensils’ handles are secured to the tang by pins visible against the mother-of-pearl. Punched brass bands inlaid with stained horn mark a transition to feather-like pommels.

This knife and fork are probably examples of Haban wares, made by Hutterites, a sect of Anabaptists who moved as a group between Germany, Austria, and Moravia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Although they practiced an ascetic lifestyle, cutlery, ceramics, shoes, and clocks crafted by the Hutterites in collective settings were highly regarded for their skill and quality. The utensils’ handles are secured to the tang by pins visible against the mother-of-pearl. Punched brass bands inlaid with stained horn mark a transition to feather-like pommels.

The design of these knife and fork handles has been attributed to the circle of Swiss goldsmith Hans Peter Oeri. The handles of twisted brass terminate in basilisk heads and were likely cast in two parts, then assembled and chased. The long twin prongs of the fork suggest that this set may have been used by a carver, perhaps for fruit or small birds. The saber-like steel blade, indented and waved, bears an inlaid maker’s mark.

Above: Knife and fork, Italy, 17th century. Steel and brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of R. Stuyvesant, 1893, 93.13.19, 20.

The design of these knife and fork handles has been attributed to the circle of Swiss goldsmith Hans Peter Oeri. The handles of twisted brass terminate in basilisk heads and were likely cast in two parts, then assembled and chased. The long twin prongs of the fork suggest that this set may have been used by a carver, perhaps for fruit or small birds. The saber-like steel blade, indented and waved, bears an inlaid maker’s mark.

*Knives and Forks* This double-edged steel blade is engraved with a decorative border that calls attention to the serrations on its spine, designed for sawing through foods with thick or resistant surfaces. The serrations mark off the part of the knife meant to be sharpened. A brass panel is inlaid on the bolster. The handle is fashioned from undulating gadrooned bulbous forms of horn alternating with horizontal stripes of brass. It terminates in a finial that anchors the tang, the part of the blade that extends into the handle.

*Knives and Forks* This double-edged steel blade is engraved with a decorative border that calls attention to the serrations on its spine, designed for sawing through foods with thick or resistant surfaces. The serrations mark off the part of the knife meant to be sharpened. A brass panel is inlaid on the bolster. The handle is fashioned from undulating gadrooned bulbous forms of horn alternating with horizontal stripes of brass. It terminates in a finial that anchors the tang, the part of the blade that extends into the handle.

A German inscription etched into the brass hilt of this two-tined fork may be a proverb or moralizing verse referring to the pleasures of roasted wild game. Additional motifs such as a deer and a female figure wearing a kerchief and an apron suggest it was used in a rustic context. The small size recalls the kinds of forks used by carvers in the illustrated manuals to spear roast fowl or fruit.

Above: Fork, possibly Switzerland, Late 17th century. Steel and brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of R. Stuyvesant, 1891, 91.16.96.

A German inscription etched into the brass hilt of this two-tined fork may be a proverb or moralizing verse referring to the pleasures of roasted wild game. Additional motifs such as a deer and a female figure wearing a kerchief and an apron suggest it was used in a rustic context. The small size recalls the kinds of forks used by carvers in the illustrated manuals to spear roast fowl or fruit.

Prints were an important source of motifs for a variety of objects in the early modern period. The ivory handle of this knife takes the form of a muscular male torso with an upturned face and foliate skirt, scrolls replacing his arms. The figure is reminiscent of architectural prints by the Flemish artist Hans Vredeman de Vries. A piece of ivory appears to have fallen off the front of the figure, while the back is intact. The double-edged blade has an elegant scroll-like detail on the spine.

Prints were an important source of motifs for a variety of objects in the early modern period. The ivory handle of this knife takes the form of a muscular male torso with an upturned face and foliate skirt, scrolls replacing his arms. The figure is reminiscent of architectural prints by the Flemish artist Hans Vredeman de Vries. A piece of ivory appears to have fallen off the front of the figure, while the back is intact. The double-edged blade has an elegant scroll-like detail on the spine.

Above / Right: Carving knife, possibly Flanders, first quarter of the 17th century. Ivory and steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Giles Whiting, 1962, 62.118.1.

Above: Carving knife, possibly Flanders, first quarter of the 17th century. Ivory and steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Giles Whiting, 1962, 62.118.1.

The handle of this long two-tined fork is made from the coronet of an antler where it was once attached to the skull of the deer. Its craggy channels form the beard and hair of a male face recalling those featured on Bartman or Bellarmine stoneware jugs. A banded silver guard anchors the fork’s tang. With its sylvan associations, antler was a desirable material for implements that might help carve or serve the spoils of the hunt.

Above: Fork, mid- to late 18th century. Antler, steel, and silver. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, The Robert L. Metzenberg Collection, Gift of Eleanor L. Metzenberg, 1985-103-155a.

The handle of this long two-tined fork is made from the coronet of an antler where it was once attached to the skull of the deer. Its craggy channels form the beard and hair of a male face recalling those featured on Bartman or Bellarmine stoneware jugs. A banded silver guard anchors the fork’s tang. With its sylvan associations, antler was a desirable material for implements that might help carve or serve the spoils of the hunt.

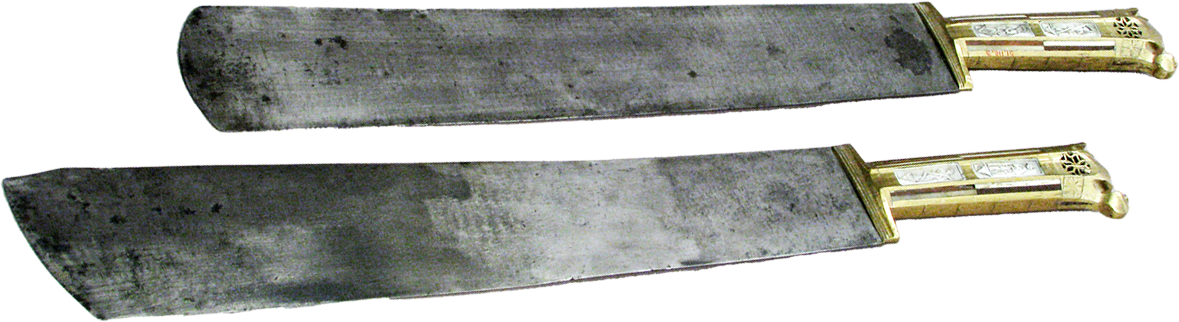

Broad, flat blades such as this are often called presentation or serving knives. Attributed to Hans Sumersperger, knifesmith of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, their brass handles are inlaid with strips of bone and walnut that frame central plaques of mother-of-pearl with incised images of the Virgin and Child, the Crucifixion, and various saints. They look similar to Burgundian knife sets that became popular after Maximilian’s marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477. Likely part of a set that included knives with sharper blades for slicing, they may have been used on the hunt or in the banquet hall to carve or convey meat to the plates of diners. One of the blades has been repaired.

Broad, flat blades such as this are often called presentation or serving knives. Attributed to Hans Sumersperger, knifesmith of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, their brass handles are inlaid with strips of bone and walnut that frame central plaques of mother-of-pearl with incised images of the Virgin and Child, the Crucifixion, and various saints. They look similar to Burgundian knife sets that became popular after Maximilian’s marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477. Likely part of a set that included knives with sharper blades for slicing, they may have been used on the hunt or in the banquet hall to carve or convey meat to the plates of diners. One of the blades has been repaired.

Above / Right: Attributed to Hans Sumersperger, two serving knives, Austria, 15th-16th century. Steel, brass, wood, bone, mother-of-pearl, and leather. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1951, 51.118.1–3.

Engraved brass bands alternate with inlaid mother-of-pearl notched wheels on the faceted horn handle of this fork. Its long tines suggest it may have been used for carving smaller birds or fruits in aria as in the illustrations from manuals by Mattia Giegher or Antonio Latini.

Above: Fork, possibly France, ca. 1650. Steel, horn, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and brass. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, The Robert L. Metzenberg Collection, Gift of Eleanor L. Metzenberg, 1985-103-59.

Engraved brass bands alternate with inlaid mother-of-pearl notched wheels on the faceted horn handle of this fork. Its long tines suggest it may have been used for carving smaller birds or fruits in aria as in the illustrations from manuals by Mattia Giegher or Antonio Latini.

Left: Fork, possibly France, ca. 1650. Steel, horn, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and brass. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, The Robert L. Metzenberg Collection, Gift of Eleanor L. Metzenberg, 1985-103-59.

Fashioned from a single piece of steel, the double-edged blade has serrations on the spine and engraved lozenge forms on the bolster. The deeply grooved spiral handle, large knob protruding from the bolster, and front quillon would have enabled a firm grip for the carving of greasy meats, anchoring thumb and forefinger.

Fashioned from a single piece of steel, the double-edged blade has serrations on the spine and engraved lozenge forms on the bolster. The deeply grooved spiral handle, large knob protruding from the bolster, and front quillon would have enabled a firm grip for the carving of greasy meats, anchoring thumb and forefinger.

The central roundel of the ivory hilt of this knife depicts a classicizing profile of a warrior, his corkscrew tendrils flowing out from a mask-like helmet. A putto stands above this, his outstretched arms grasping the legs of acrobats clinging to the backs of dragons, from whose gaping maws yet more figures emerge. A female profile on the other side features similar serpentine locks. On the lower section of the handle, another putto balances atop an ovoid form, against a patterned background formed of small oculi. The curved and notched blade is engraved with a foliate pattern.

The central roundel of the ivory hilt of this knife depicts a classicizing profile of a warrior, his corkscrew tendrils flowing out from a mask-like helmet. A putto stands above this, his outstretched arms grasping the legs of acrobats clinging to the backs of dragons, from whose gaping maws yet more figures emerge. A female profile on the other side features similar serpentine locks. On the lower section of the handle, another putto balances atop an ovoid form, against a patterned background formed of small oculi. The curved and notched blade is engraved with a foliate pattern.

Above: Knife, Portugal, 16th century. Ivory and steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, 64.101.1598.

Above: Knife, Portugal, 16th century. Ivory and steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, 64.101.1598.