*Folding by the Book*

*Folding by the Book*

he craft of pleating and folding starched linen napkins to adorn a festive table dates back at least to the sixteenth century. Stewards, who prepared the linens and set the tables, played an important role in these live performances alongside the carvers, who were responsible for slicing and dicing before diners at the table, and the chefs, who prepared the food itself.

he craft of pleating and folding starched linen napkins to adorn a festive table dates back at least to the sixteenth century. Stewards, who prepared the linens and set the tables, played an important role in these live performances alongside the carvers, who were responsible for slicing and dicing before diners at the table, and the chefs, who prepared the food itself.

Although illustrated instructions for napkin-folding emerged only in the early seventeenth century, folding and pleating techniques have a long history. In antiquity and the Middle Ages, folding papyrus, parchment, or paper was a means to conceal or protect information written thereon. Pleating fabric enabled clothing to take on the shape of the body that it was covering. One of the earliest texts to describe the layering and folding of linen coverings for the table, for bread, and for cutlery is John Russell’s early fifteenth-century Boke of Nurture. In the course of the sixteenth century, the artful folding of table linens became de rigueur at courts across the continent, stimulating the publication of the illustrated manuals on view in this exhibition.

Above: Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, Padua, 1639), plate 2. Engraving. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1639.

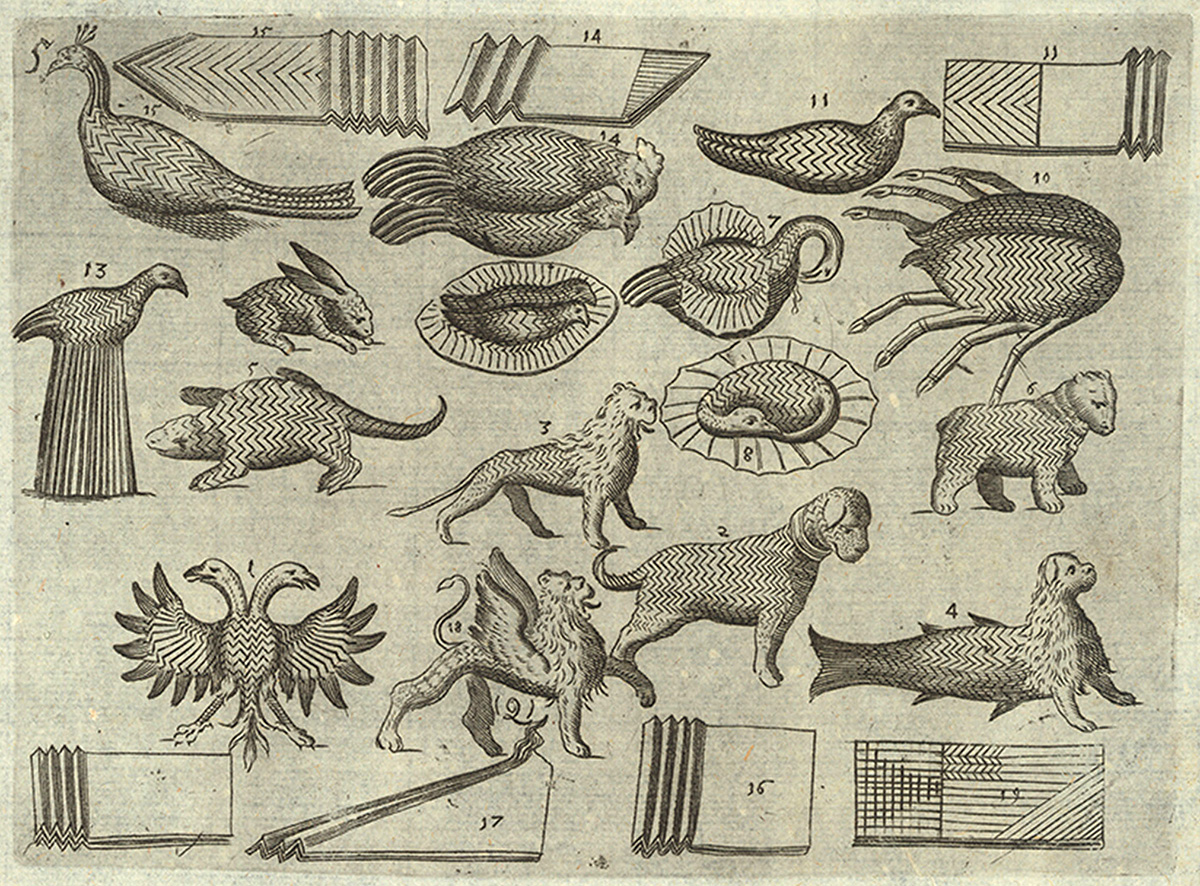

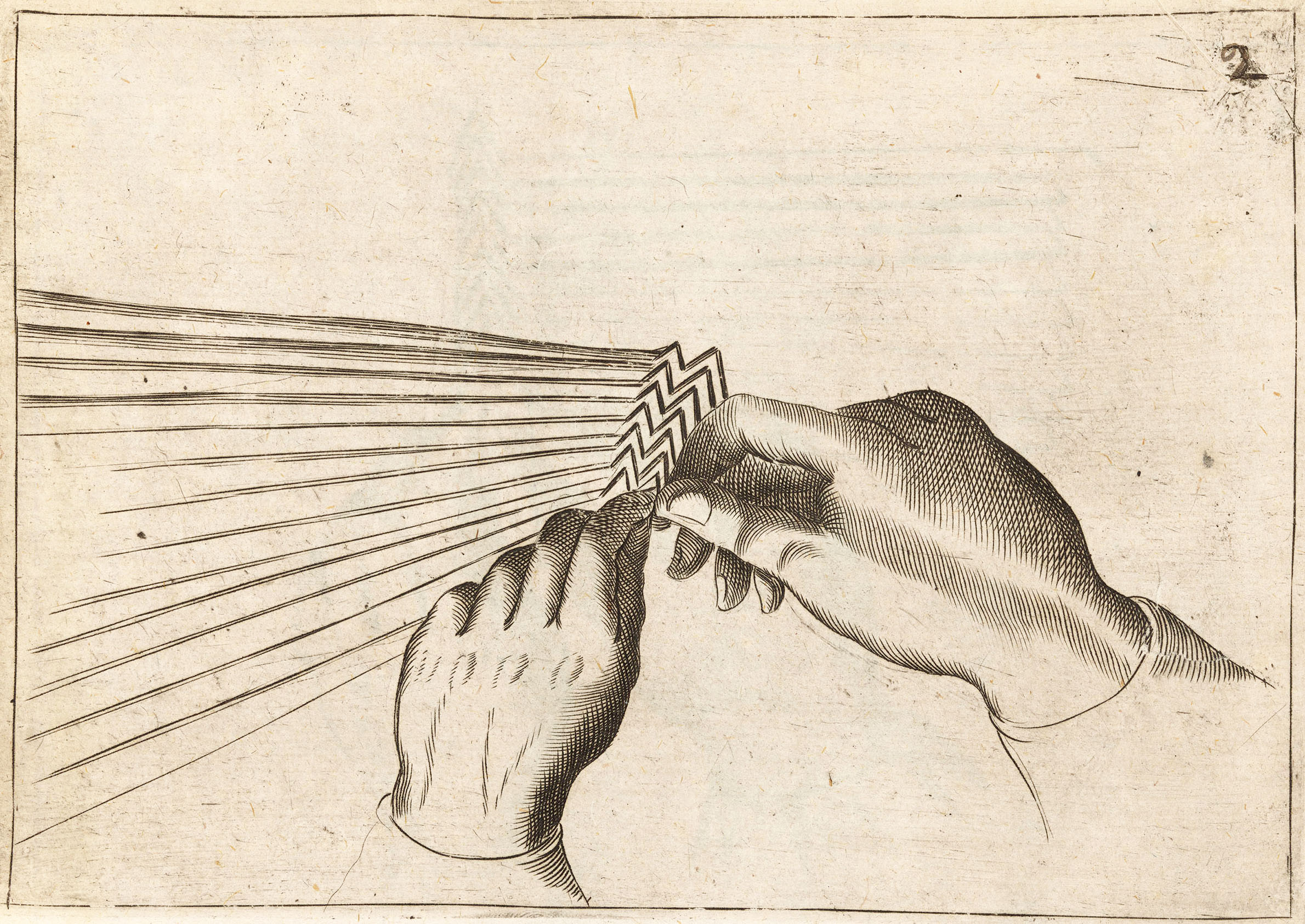

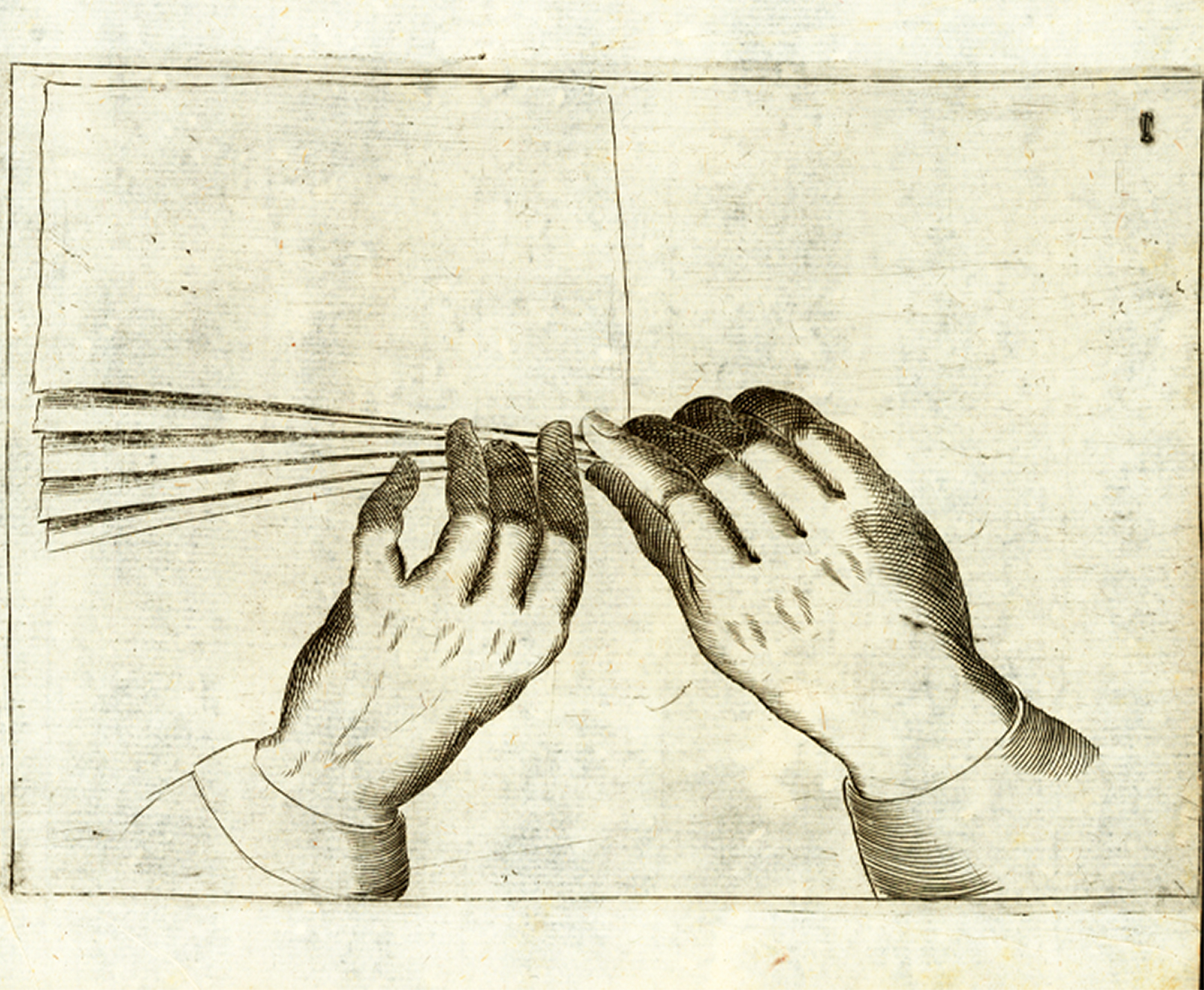

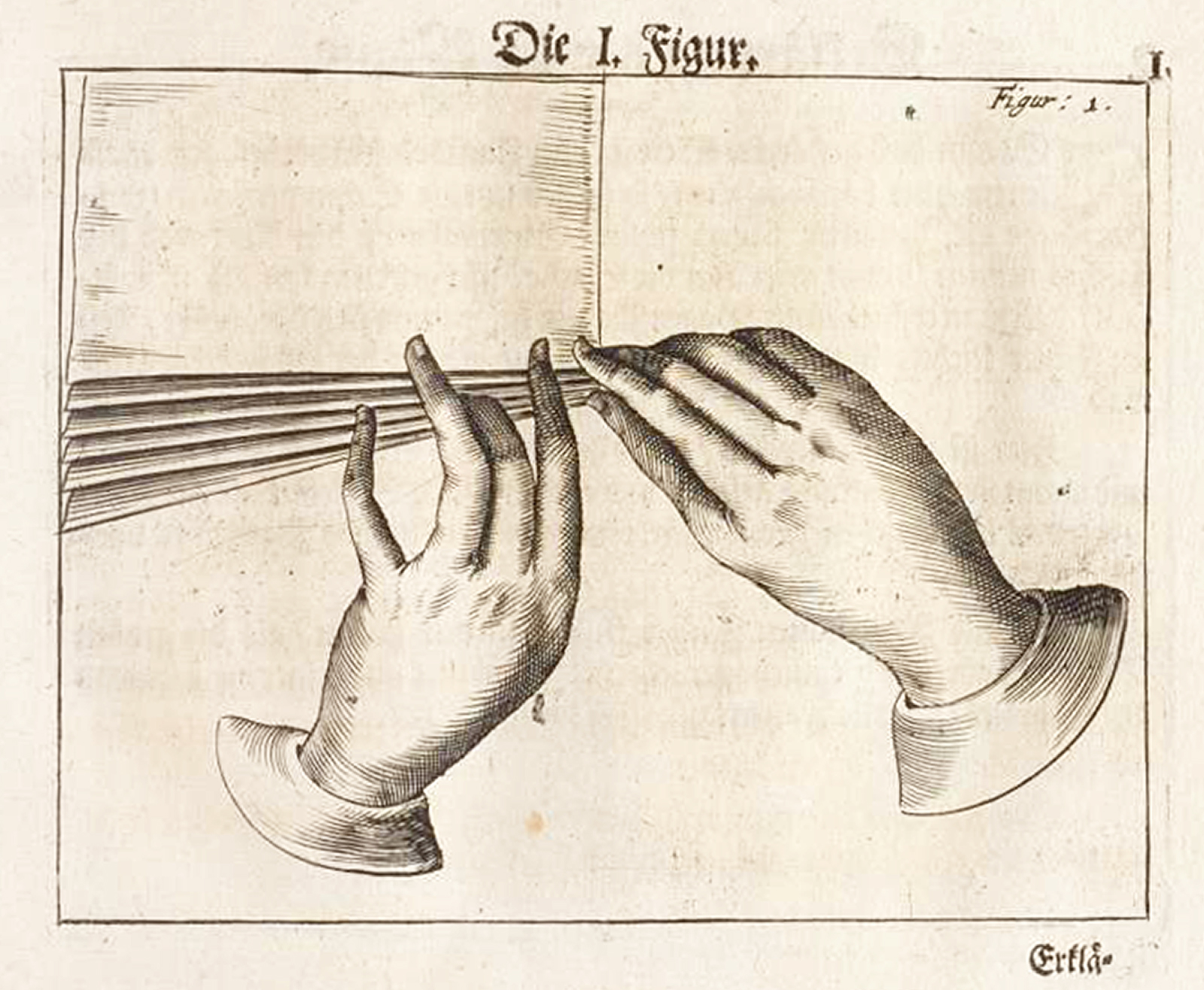

*Diagrams & Demonstrations* Sixteenth-century carving manuals such those of Giovanni Francesco Colle and Vincenzo Cervio depict the carver’s utensils: forks, knives, steels, scoops, and so on. Mattia Giegher pushes the genre of illustrated technical manual to a new level by activating the tools in the hands of the artisan wielding them. These eerily disembodied hands are among the first to appear in the carving and folding books. On the left below is the first of three diagrams in Giegher’s treatise on folding, first published in 1629, demonstrating the first step to creating the elaborate centerpieces on display here. The caption for this image, included on another page, reads, “Il secondo disegno delle dette mani aditta il modo di cominciar lo spinapesce” (the second drawing of the said hands instructs how to begin the fish scales). He claims that the book will “show with great ease the way to fold any kind of linen fabrics, that is, napkins and tablecloths” and that they are “a totally new invention by the author, never seen before.” Georg Philipp Harsdörffer reproduced the three basic folding diagrams from Giegher. On the right below is Harsdörffer’s first folding diagram, labeled clearly as such. These are the basic “long folds,” translated as Langfalten in German.

*Diagrams and Demonstrations* Sixteenth-century carving manuals such those of Giovanni Francesco Colle and Vincenzo Cervio depict the carver’s utensils: forks, knives, steels, scoops, and so on. Mattia Giegher pushes the genre of illustrated technical manual to a new level by activating the tools in the hands of the artisan wielding them. These eerily disembodied hands are among the first to appear in the carving and folding books. Below is the first of three diagrams in Giegher’s treatise on folding, first published in 1629, demonstrating the first step to creating the elaborate centerpieces on display here. The caption for this image, included on another page, reads, “Il secondo disegno delle dette mani aditta il modo di cominciar lo spinapesce” (the second drawing of the said hands instructs how to begin the fish scales). He claims that the book will “show with great ease the way to fold any kind of linen fabrics, that is, napkins and tablecloths” and that they are “a totally new invention by the author, never seen before.” Georg Philipp Harsdörffer reproduced the three basic folding diagrams from Giegher. The following image is Harsdörffer’s first folding diagram, labeled clearly as such. These are the basic “long folds,” translated as Langfalten in German.

Above: Mattia Giegher, “Plate 1,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

Above: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Die I Figur,” from Vollständiges vermehrtes Trincir-Buch (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1652). Engraving. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine Library.

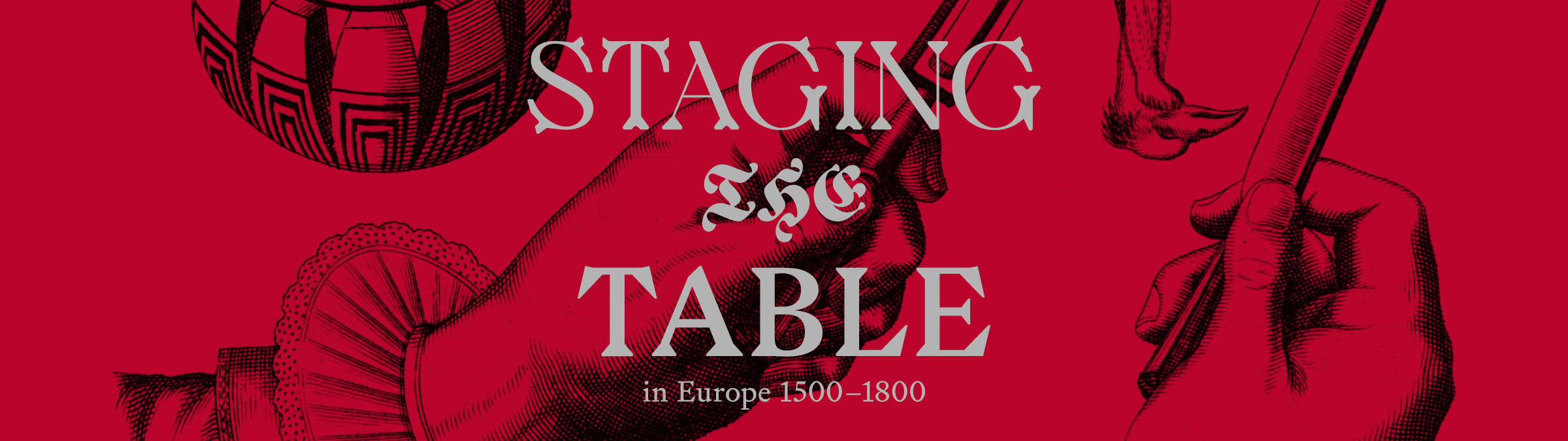

The long title of this small book describes instructions for a number of skills and techniques: how to speak courteously and pay compliments; how to make many kinds of invisible inks; how to carve meats, fowl, fish, and fruit; and how to fold napkins. Like so many volumes, it makes use of foldout pages to literally expand its impact. The leaf on view here shows the basic four folds used to create several sculpted napkins that are illustrated, including a mountain with two peaks and a sea crab.

Above: “Alls aus diese Viere” folding instructions, from Neu A la modisch Nach itziger gebräuchlichen Arth eingerichtetes Complementir-Frisier-Trenchier- und Kunst-Buch (Hamburg: Thomas von Wiering, ca. 1700). Engraving. Conjuring Arts Research Center.

The long title of this small book describes instructions for a number of skills and techniques: how to speak courteously and pay compliments; how to make many kinds of invisible inks; how to carve meats, fowl, fish, and fruit; and how to fold napkins. Like so many volumes, it makes use of foldout pages to literally expand its impact. The leaf on view here shows the basic four folds used to create several sculpted napkins that are illustrated, including a mountain with two peaks and a sea crab.

Left: “Alls aus diese Viere” folding instructions, from Neu A la modisch Nach itziger gebräuchlichen Arth eingerichtetes Complementir-Frisier-Trenchier- und Kunst-Buch (Hamburg: Thomas von Wiering, ca. 1700). Engraving. Conjuring Arts Research Center.

Follow along as contemporary folding artist Joan Sallas demonstrates techniques for creating a folded napkin shape based on a diagram from an early modern handbook.

Right: Joan Sallas, “Gezackter Fächer” (serrated fan), after Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambot- to, 1639). No audio.

From Tischlein deck dich: 11 Napkin Folding Tutorials

© 2008 Franz Große. All rights reserved.

Follow along as contemporary folding artist Joan Sallas demonstrates techniques for creating a folded napkin shape based on a diagram from an early modern handbook.

Above: Joan Sallas, “Gezackter Fächer” (serrated fan), after Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambot- to, 1639). No audio.

From Tischlein deck dich: 11 Napkin Folding Tutorials

© 2008 Franz Große. All rights reserved.

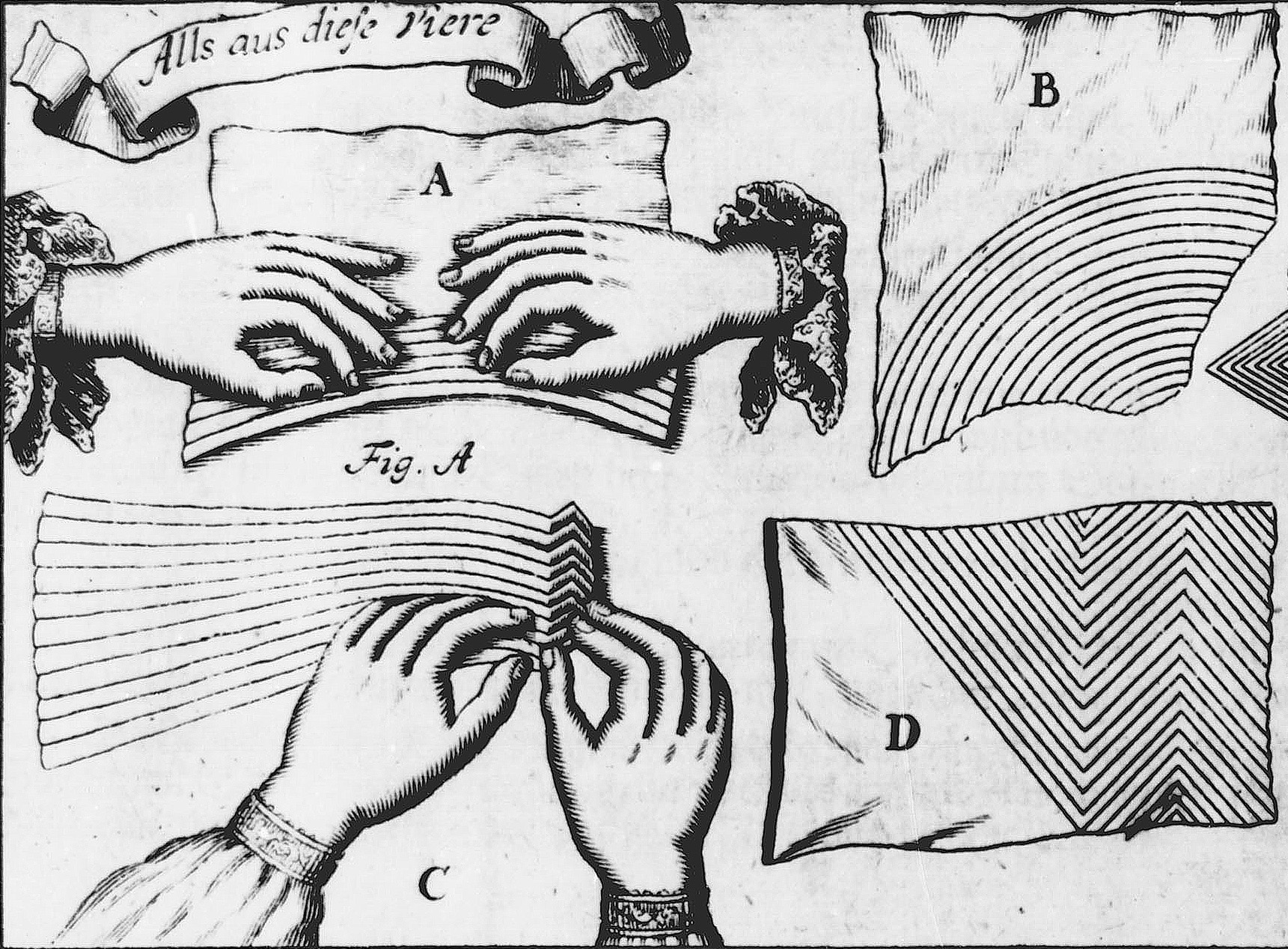

*Elaborate Shapes* Napkins were folded and pleated into elaborate shapes, such as large fowl, mythical beasts, architectural forms, or heraldic symbols. Some were unfurled to protect diners’ clothing; others were purely ornamental. These soft furnishings took their place beside sculptures of sugar paste, butter, or ice, as well as more durable materials such as ceramic, metal, or stone. They were known in Italian as Trionfi da Tavola and in German as Schauessen or Shaugericheten, depending on if they were intended to be eaten or simply admired.

No folded napkins or centerpieces have survived from the early modern period, but detailed manuals such as those written by Mattia Giegher and Andreas Klett have enabled contemporary folding artist Joan Sallas to reconstruct some of these objects.

As he discovered, the fabric was heavily starched and probably moistened to hold the shape. Thread and needle could have been used to hold a point, or a piece of bread used as a support, though these auxiliary materials are not mentioned in the treatises. To save the labor and expense involved in the preparation of linen, paper was used for practice. This connection brought the art of folding linen into conversation with the teaching of geometry and recreational mathematics, a popular form of entertainment in early modern Europe.

Above: Mattia Giegher, “Plate 5,” from Per fare animali di spinapesce (To make animals with herringbone pleats) (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

Above: Mattia Giegher, “Plate 5,” from Per fare animali di spinapesce (To make animals with herringbone pleats) (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

As he discovered, the fabric was heavily starched and probably moistened to hold the shape. Thread and needle could have been used to hold a point, or a piece of bread used as a support, though these auxiliary materials are not mentioned in the treatises. To save the labor and expense involved in the preparation of linen, paper was used for practice. This connection brought the art of folding linen into conversation with the teaching of geometry and recreational mathematics, a popular form of entertainment in early modern Europe.

* * *

* * *

*Eagle* The double-headed eagle was a potent symbol of empire from the Byzantine period and was one of several heraldic beasts in Mattia Giegher’s linen menagerie. In the seventeenth century, it was primarily associated with the Hapsburg family and might have been deployed at a function to honor a member of that far-ranging dynasty, or loyalties thereof. This work was folded in 2022 based on illustrations in Giegher’s 1629 Li Tre Trattati, the first text to print instructions for folding napkins and linen centerpieces, or trionfi.

Above: Joan Sallas, “Aquila” (Eagle), after Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . ., 2022. Starched linen napkin, cut, with herringbone and closed folds. PADORE – Archive for Documentation and Research of Historical Folding Art.

*Eagle* The double-headed eagle was a potent symbol of empire from the Byzantine period and was one of several heraldic beasts in Mattia Giegher’s linen menagerie. In the seventeenth century, it was primarily associated with the Hapsburg family and might have been deployed at a function to honor a member of that far-ranging dynasty, or loyalties thereof. This work was folded in 2022 based on illustrations in Giegher’s 1629 Li Tre Trattati, the first text to print instructions for folding napkins and linen centerpieces, or trionfi.

* * *

* * *

*Turkey* The strength to hold a turkey aloft while carving was a qualifying attribute of an ideal carver. Turkeys arrived in Seville in 1511 under the auspices of King Ferdinand of Spain and were immediately welcomed on tables across Europe. They appear in a number of recipe books from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

*Turkey* The strength to hold a turkey aloft while carving was a qualifying attribute of an ideal carver. Turkeys arrived in Seville in 1511 under the auspices of King Ferdinand of Spain and were immediately welcomed on tables across Europe. They appear in a number of recipe books from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Right: Joan Sallas, “Ein Welscher Han” (Turkey), after Andreas Klett, Neues Trenchir-und Plicatur-Büchlein . . ., 2010. Two starched linen napkins, herringbone and pleated folds. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

* * *

* * *

Above: Joan Sallas, “Fisch mit Floss-Federn” (Fish with rippling feathers, likely a pike), after Andreas Klett, Neues Trenchir-und Plicatur-Büchlein . . ., 2010. Starched linen napkin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

*Crab* Recipes for many kinds of crab are featured in Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera, and instructions for sectioning and serving can be found in Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante as well as Mattia Giegher’s Li Tre Trattati.

Above: Joan Sallas, “Il granciporo, e granchio di mare” (Crab, and sea crab), after Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . ., 2010. Starched linen napkin with herringbone folds, pleated, and cut legs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

*Crab* Recipes for many kinds of crab are featured in Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera, and instructions for sectioning and serving can be found in Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante as well as Mattia Giegher’s Li Tre Trattati.

Left: Joan Sallas, “Il granciporo, e granchio di mare” (Crab, and sea crab), after Mattia Giegher, Li Tre Trattati . . ., 2010. Starched linen napkin with herringbone folds, pleated, and cut legs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.