*Linens*

*Linens*

inen had many uses in the early modern period: bedding; clothing, including undergarments; and the dressing of the table. Made from flax, which was cultivated all over Europe from the Middle Ages onward, its processing was labor intensive, from plant to fiber to yarn to finished textile. Fine linens were generally woven with either a small geometric repeated pattern or figurative patterns known as damasks, with larger repeats that often told stories or featured naturalistic motifs.

inen had many uses in the early modern period: bedding; clothing, including undergarments; and the dressing of the table. Made from flax, which was cultivated all over Europe from the Middle Ages onward, its processing was labor intensive, from plant to fiber to yarn to finished textile. Fine linens were generally woven with either a small geometric repeated pattern or figurative patterns known as damasks, with larger repeats that often told stories or featured naturalistic motifs.

Perhaps inspired by damask-patterned silks, which originated in Asia and were named after inlaid metalwork from Damascus, white linen table damasks were first produced by weavers in the Southern Netherlands. Many skilled artisans left Flanders in 1585 with the fall of Antwerp and moved to Holland, where the linen trade flourished. The linen that Mattia Giegher, Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, and their readers desired for their tables would likely have been imported, woven, and bleached in present-day Belgium or the Netherlands. Some of the folded napkins may even have been created using white linen damasks such as those on view here. As inventories from the period document, affluent families may have owned hundreds of pieces of fine linen, some with family crests or other personal markers, commissioned to commemorate marriages or other alliances.

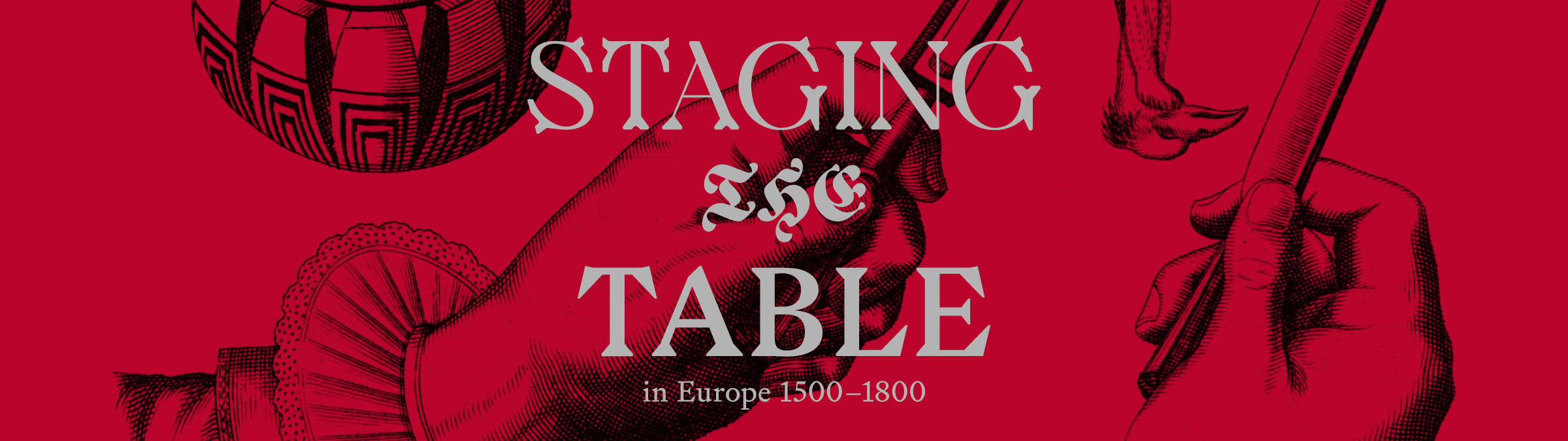

Above: Joan Sallas, “Funff Berge” (Five Mountains), after Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, Vollständig vermerhtes Trincir-Buch (Nuremberg, 1652), 2010. Saxon starched linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

*Elegant Figures* The guests are just arriving, perhaps waiting to greet the host or hostess. Most wear crisply pleated starched linen ruffs, symbols of wealth and status. On the balcony, an ensemble plays music, while the “credenziere” folds a napkin at the credenza, which is loaded with silver, gold, and glass vessels. A man enters from the adjacent kitchen, bearing a pie crowned by a peacock, and several more pies topped by swans or peacocks punctuate the center of the U-shaped table. Napkins folded into peaks stand at attention. Once the diners take their places, the napkins will be unfurled, their crisp folds dissolving into square footage to protect the guests’ finery.

*Elegant Figures* The guests are just arriving, perhaps waiting to greet the host or hostess. Most wear crisply pleated starched linen ruffs, symbols of wealth and status. On the balcony, an ensemble plays music, while the “credenziere” folds a napkin at the credenza, which is loaded with silver, gold, and glass vessels. A man enters from the adjacent kitchen, bearing a pie crowned by a peacock, and several more pies topped by swans or peacocks punctuate the center of the U-shaped table. Napkins folded into peaks stand at attention. Once the diners take their places, the napkins will be unfurled, their crisp folds dissolving into square footage to protect the guests’ finery.

Above: Louis de Caullery, Elegant Figures Congregating in a Banqueting Hall, before 1621. Oil on panel. Private collection, Rafael Valls Gallery London, Bridgeman Images.

Above: Louis de Caullery, Elegant Figures Congregating in a Banqueting Hall, before 1621. Oil on panel. Private collection, Rafael Valls Gallery London, Bridgeman Images.

Sculpted linens can be seen in visual records of banquets such the well-known drawings by Pierre Paul Sevin, a French artist who spent time at the French Academy in Rome in the 1660s. Sevin recorded long tables laden with characteristic Baroque pyramids of fruit, vases of cut flowers, folded linens, and a great variety of sculptural forms that may have been made of sugar paste, possibly gilded or bronzed, or more permanent materials.

Sculpted linens can be seen in visual records of banquets such the well-known drawings by Pierre Paul Sevin, a French artist who spent time at the French Academy in Rome in the 1660s. Sevin recorded long tables laden with characteristic Baroque pyramids of fruit, vases of cut flowers, folded linens, and a great variety of sculptural forms that may have been made of sugar paste, possibly gilded or bronzed, or more permanent materials. This drawing of what was probably a banquet celebrating Leopoldo de’ Medici’s investiture as cardinal in December of 1667 depicts an elaborate tabletop display with a marine theme, including Neptune and his horses, tritons blowing horns and riding fish, and what appears to be a terrine surrounded by nereids and mermaids, which suggests that the banquet was held on a fish day, when the Catholic calendar forbade the eating of meat. All the figure groups stand on dishes, suggesting that they are fashioned of edible media. Sevin might have had a chance to sketch these festive displays before the event, since laid tables would be made accessible to visitors for a few days before the actual banquet.

Above: Pierre Paul Sevin, Banquet Table with Trionfi for Cardinal Leopoldo de’Medici’s Investiture, 1667?. Pencil and brown ink, layering in gray, on paper. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMH THC 3612.

Above: Pierre Paul Sevin, Banquet Table with Trionfi for Cardinal Leopoldo de’Medici’s Investiture, 1667?. Pencil and brown ink, layering in gray, on paper. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMH THC 3612.

This drawing of what was probably a banquet celebrating Leopoldo de’ Medici’s investiture as cardinal in December of 1667 depicts an elaborate tabletop display with a marine theme, including Neptune and his horses, tritons blowing horns and riding fish, and what appears to be a terrine surrounded by nereids and mermaids, which suggests that the banquet was held on a fish day, when the Catholic calendar forbade the eating of meat. All the figure groups stand on dishes, suggesting that they are fashioned of edible media. Sevin might have had a chance to sketch these festive displays before the event, since laid tables would be made accessible to visitors for a few days before the actual banquet.

In the text that accompanies the image, Georg Philipp Harsdörffer describes the effect of this tablescape as “flamed” and “wave-like.” Once the food was served, the weight of bowls, plates, and candelabra would flatten the peaks as the next act of the meal was played out.

Right: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Rund Tafel,” from Vollständig vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . , page 325 (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1657). Engraving. Courtesy the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

In the text that accompanies the image, Georg Philipp Harsdörffer describes the effect of this tablescape as “flamed” and “wave-like.” Once the food was served, the weight of bowls, plates, and candelabra would flatten the peaks as the next act of the meal was played out.

Above: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Rund Tafel,” from Vollständig vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . , page 325 (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1657). Engraving. Courtesy the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

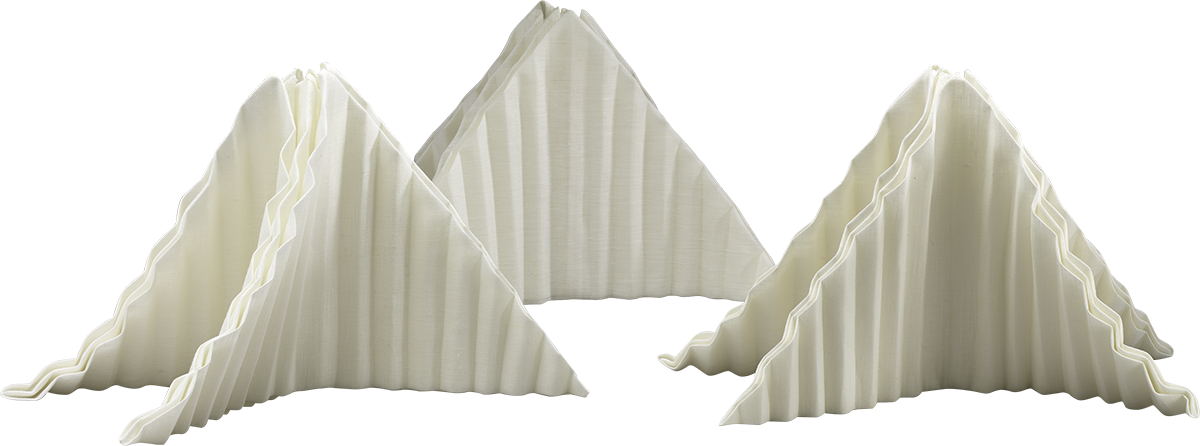

*Dressing the Table* This white linen damask napkin was likely made in Haarlem, Holland, in 1663. It commemorates the wedding, sixteen years earlier, of Jonkheer Doecke Martena van Burmania, a wealthy mayor from a venerable family, to Edwarda Lucia Van Juckema. Their names and the date of the napkin’s production are woven into the fabric, with the appellation in Dutch: “Lord of the manor, and keeper of the dikes, 1663.” An elaborate floral border with the Van Burmania crest in the corners frames two scenes from the story of Abraham, Sarah, and Isaac. Above, Abraham sits on a stool while two angels announce that he will father a son. His wife Sarah is visible in the background. In the lower zone, Abraham kneels before an altar swinging an incense burner. The smoke rises to frame the tetragrammaton. A ram in a thicket, offered in thanks, can be seen above. Embroidered numerals in the upper right corner indicate that it was part of a set of twenty-four.

*Dressing the Table* This white linen damask napkin was likely made in Haarlem, Holland, in 1663. It commemorates the wedding, sixteen years earlier, of Jonkheer Doecke Martena van Burmania, a wealthy mayor from a venerable family, to Edwarda Lucia Van Juckema. Their names and the date of the napkin’s production are woven into the fabric, with the appellation in Dutch: “Lord of the manor, and keeper of the dikes, 1663.” An elaborate floral border with the Van Burmania crest in the corners frames two scenes from the story of Abraham, Sarah, and Isaac. Above, Abraham sits on a stool while two angels announce that he will father a son. His wife Sarah is visible in the background. In the lower zone, Abraham kneels before an altar swinging an incense burner. The smoke rises to frame the tetragrammaton. A ram in a thicket, offered in thanks, can be seen above. Embroidered numerals in the upper right corner indicate that it was part of a set of twenty-four.

Right: Napkin with the story of Abraham and Isaac, [Haarlem?], 1663. Linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. A. P. A. Vorenkamp, 1944, 44.115.

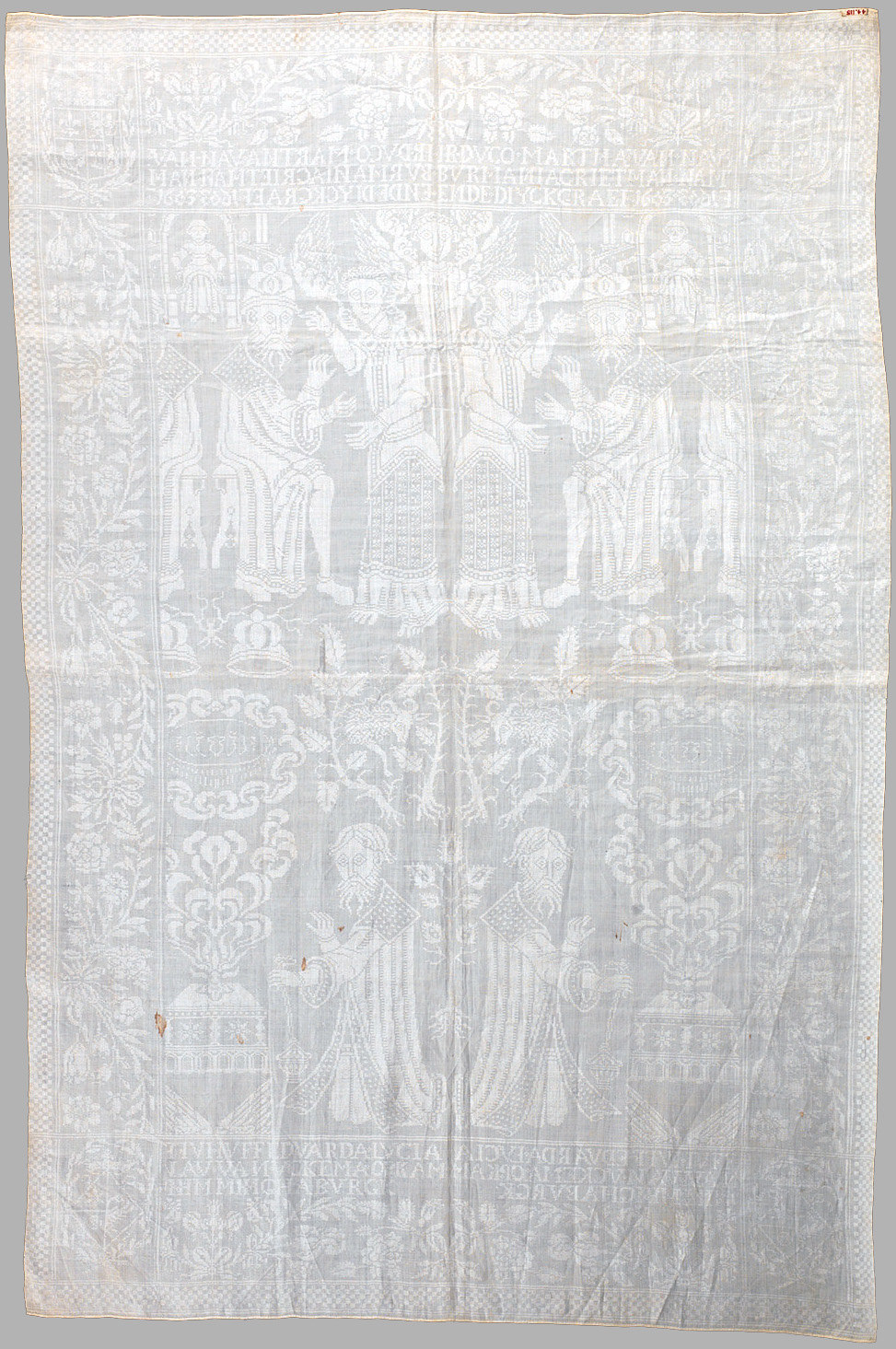

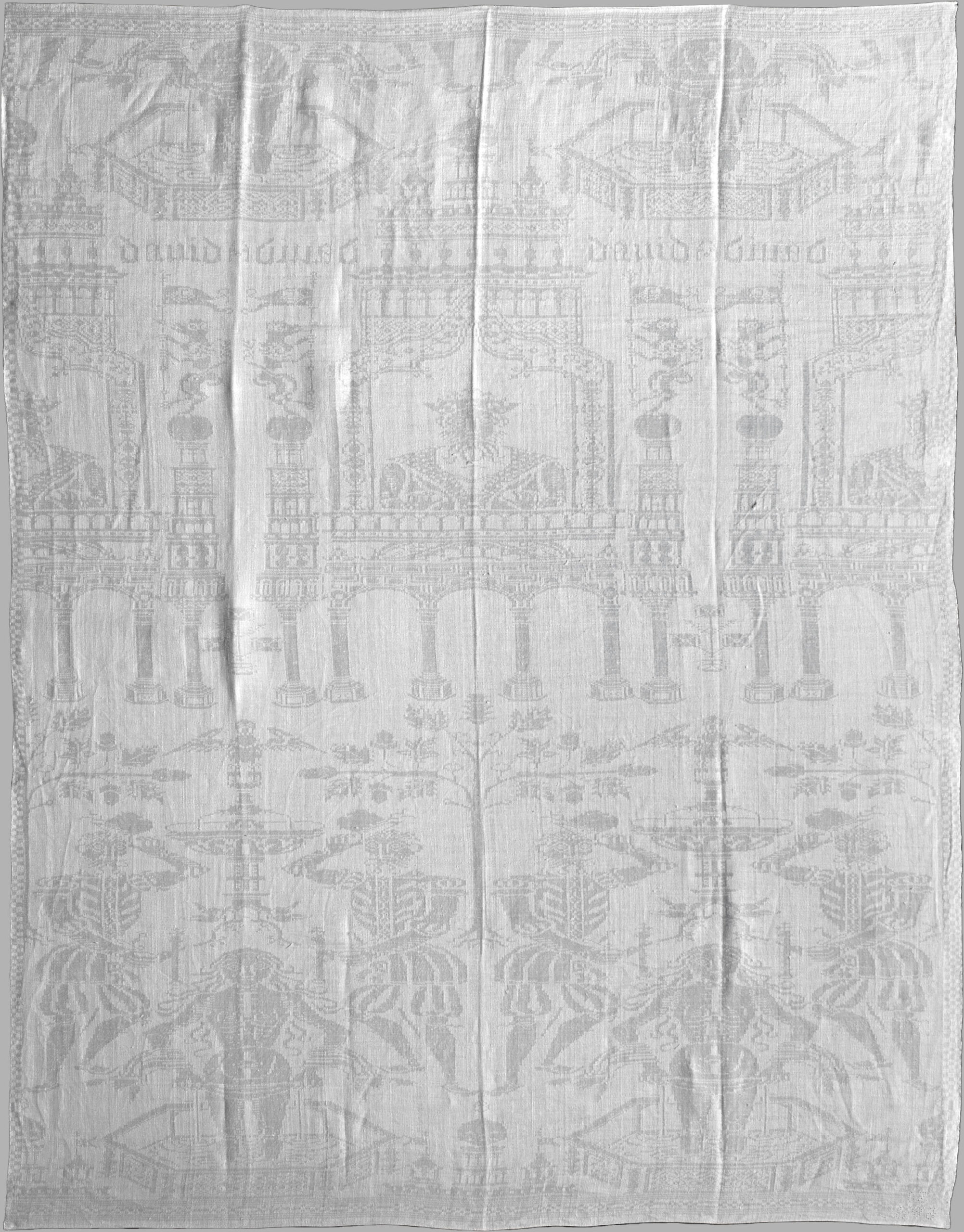

The imagery on linen damask napkins and tablecloths often drew inspiration from the bible, as in this example. King David, looking out from a turreted palace at the center of the napkin, is labeled in gothic script, “Davidt.” Below, Bathsheba bathes naked in a hexagonal fountain. David, aroused by this sight, has sent his men to bring her to him. A frequently illustrated story in this period, Bathsheba is generally represented with female attendants who try to shield her from prying eyes, emphasizing her modesty. In this more economical rendition, David’s henchmen are standing by the fountain, about to carry her off, suggesting David’s coercion and removing any suspicion of Bathsheba’s own role in her seduction and subsequent elevation to queen. The vertical repeat of the weave has left a small amount of Bathsheba’s fountain visible at the top of the object. The napkin is bordered by a pattern of small checkerboard. An inscription in white drawn work, PAV 20, may indicate the total number of napkins in the set.

Above: Napkin with David and Bathsheba, Netherlands, ca. 1590–1600. Linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sperone Westwater Inc. and The James Parker Charitable Foundation Gifts, 2010, 2010.19.

The imagery on linen damask napkins and tablecloths often drew inspiration from the bible, as in this example. King David, looking out from a turreted palace at the center of the napkin, is labeled in gothic script, “Davidt.” Below, Bathsheba bathes naked in a hexagonal fountain. David, aroused by this sight, has sent his men to bring her to him. A frequently illustrated story in this period, Bathsheba is generally represented with female attendants who try to shield her from prying eyes, emphasizing her modesty. In this more economical rendition, David’s henchmen are standing by the fountain, about to carry her off, suggesting David’s coercion and removing any suspicion of Bathsheba’s own role in her seduction and subsequent elevation to queen. The vertical repeat of the weave has left a small amount of Bathsheba’s fountain visible at the top of the object. The napkin is bordered by a pattern of small checkerboard. An inscription in white drawn work, PAV 20, may indicate the total number of napkins in the set.

Left: Napkin with David and Bathsheba, Netherlands, ca. 1590–1600. Linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sperone Westwater Inc. and The James Parker Charitable Foundation Gifts, 2010, 2010.19.

This white linen damask napkin depicts a forest scene in which unicorns and peacocks gather around a fountain beneath the image of a woman on horseback, holding a bird of prey on her wrist. Although it was made in Europe, the label affixed to the back bears names and dates that indicate it was passed down through several generations of the American Van Horne and Jay families, starting with Anna M. Jay; her daughter, Judith Jay, born in 1698; her son Augustus Van Horne, born in 1736; his daughter Anna Mary Van Horne, bornin 1778; then Elizabeth Clarkson in 1810; and finally her daughter, Ann Mary Clarkson, in 1831. A family like this would have owned hundreds of table linens, but this one must have had special meaning, enabling it to bear witness to the passage of time much like the flyleaf of a family bible that records the birth and death dates of families over many generations.

This white linen damask napkin depicts a forest scene in which unicorns and peacocks gather around a fountain beneath the image of a woman on horseback, holding a bird of prey on her wrist. Although it was made in Europe, the label affixed to the back bears names and dates that indicate it was passed down through several generations of the American Van Horne and Jay families, starting with Anna M. Jay; her daughter, Judith Jay, born in 1698; her son Augustus Van Horne, born in 1736; his daughter Anna Mary Van Horne, bornin 1778; then Elizabeth Clarkson in 1810; and finally her daughter, Ann Mary Clarkson, in 1831. A family like this would have owned hundreds of table linens, but this one must have had special meaning, enabling it to bear witness to the passage of time much like the flyleaf of a family bible that records the birth and death dates of families over many generations.

Right: Napkin, Netherlands or Germany, ca. 1600, with later inscriptions and labels. Linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William A. Moore, 1923, 23.80.74a.

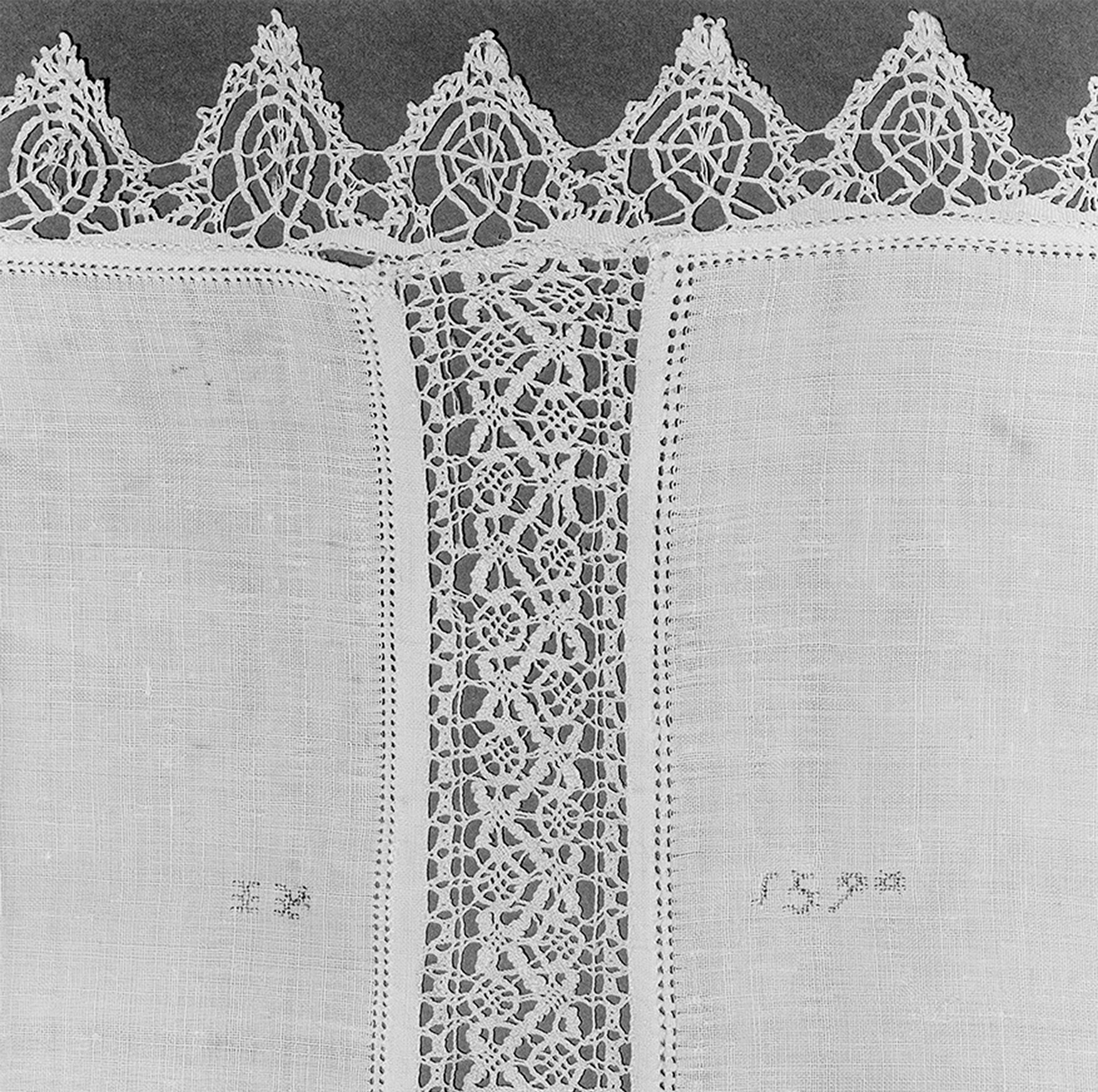

This large tablecloth is made of two lengths of plain or “tabby” weave linen joined by a panel of bobbin lace in reticella style. The ends are edged with bobbin lace inspired by punto in aria designs. The date 1590, embroidered onto the linen in pale blue silk, together with the letters “I P,” possibly initials of the maker or owner of the tablecloth, suggest that it was created to mark a special event such as a wedding.

This large tablecloth is made of two lengths of plain or “tabby” weave linen joined by a panel of bobbin lace in reticella style. The ends are edged with bobbin lace inspired by punto in aria designs. The date 1590, embroidered onto the linen in pale blue silk, together with the letters “I P,” possibly initials of the maker or owner of the tablecloth, suggest that it was created to mark a special event such as a wedding.

Left: Tablecloth, Italy, 1590. Linen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Helena Woolworth McCann Collection, Purchase, Winfield Foundation Gift, by exchange, 1975, 1975.151.

*Bleaching Fields* By the early seventeenth century, Haarlem, Holland—favored due to its plentiful water sources, grassy fields for drying the linens, and an ample supply of buttermilk from local dairies—had become the European hub for the bleaching of linens. The labor-intensive process involved soaking and washing the linen with soap and water, then boiling it in an alkaline substance for two days. Following this, it was spread on fields in the sun for up to two days, after which the process was repeated, but with an added step—that of soaking the linen in buttermilk, which enhanced the bleaching through its acidity.

*Bleaching Fields* By the early seventeenth century, Haarlem, Holland—favored due to its plentiful water sources, grassy fields for drying the linens, and an ample supply of buttermilk from local dairies—had become the European hub for the bleaching of linens. The labor-intensive process involved soaking and washing the linen with soap and water, then boiling it in an alkaline substance for two days. Following this, it was spread on fields in the sun for up to two days, after which the process was repeated, but with an added step—that of soaking the linen in buttermilk, which enhanced the bleaching through its acidity.

Right: Jacob van Ruisdael, View of the Dunes Near Bloemandael with Bleaching Fields, ca. 1670–75. Oil on canvas. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1950.498.