*The Carver*

*The Carver*

ho were the trincianti (carvers)? As courtly servants, always male, they were considered “officers of the mouth,” who worked in close proximity to their patrons. Since most diners did not have personal forks until at least the early seventeenth century, it was the job of the carver to cut food into small enough pieces to be eaten with fingers or speared on the point of a knife. The carver was also tasked with adding the proper condiments to the cooked meat as it was served.

ho were the trincianti (carvers)? As courtly servants, always male, they were considered “officers of the mouth,” who worked in close proximity to their patrons. Since most diners did not have personal forks until at least the early seventeenth century, it was the job of the carver to cut food into small enough pieces to be eaten with fingers or speared on the point of a knife. The carver was also tasked with adding the proper condiments to the cooked meat as it was served.

Many manuals include detailed instructions on the personal comportment of the carver, including his clothing, the way his nails were to be cut, and the length of his beard. He was advised to maintain olfactory discipline by avoiding onions, garlic, leeks, and cilantro, and keeping clear of smoke, horses, and foundries. The ideal carver was young, between twenty and forty years old, and strong enough to hold a turkey aloft while carving. As the first line of defense against the poisoning of his master, he was tasked with keeping his tools locked away to prevent impregnation with poison and wore rings with stones—including rubies, emeralds, and diamonds—that were believed to protect against the evil eye.

By the seventeenth century, some carvers were entrepreneurial, teaching classes and publishing their curricula. They were more than likely educated and literate. Professionals such as Mattia Giegher, Andreas Klett, and Jacques Vontet disseminated diagrams that may have originated as handouts for carving meats and fruits. They borrowed freely from one another, engaging in a broad conversation in print across Europe.

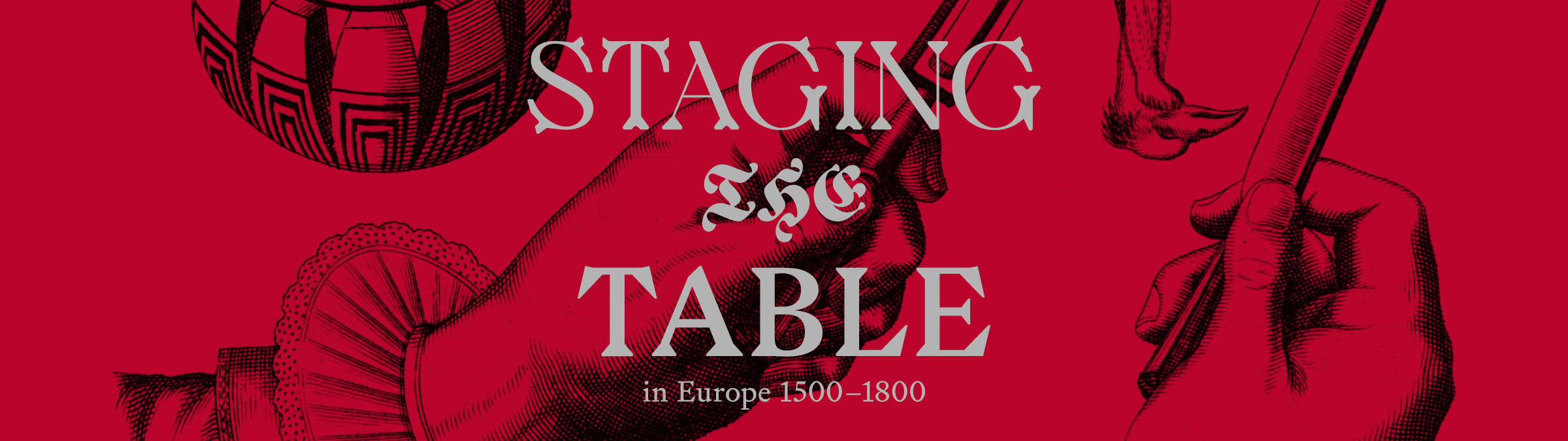

Above: Andreas Klett, frontispiece, from New Erfundenes und vollständiges Trenchir-Büchlein (Munich: Lucas Straub, 1671). Engraving. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Oecon. 986/ BV001500323.

*Carvers in Action* A tall, smiling, well-groomed carver dressed in livery brandishes a specimen aloft on a fork in his right hand, with his left holding a long knife poised to slice. He stands before a draped table with exaggerated curlicue feet, upon which rest several other dishes waiting to be carved. The scene possibly depicts wooden demonstration models.

Right: George Philipp Harsdörffer, carver, from Trincir oder Vorleg-Büchlein . . . , folio 3r. (Lepizig: Leipnitz, ca. 1635). Engraving. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Oecon, 1722 p.

*Carvers in Action* A tall, smiling, well-groomed carver dressed in livery brandishes a specimen aloft on a fork in his right hand, with his left holding a long knife poised to slice. He stands before a draped table with exaggerated curlicue feet, upon which rest several other dishes waiting to be carved. The scene possibly depicts wooden demonstration models.

Above: George Philipp Harsdörffer, carver, from Trincir oder Vorleg-Büchlein . . . , folio 3r. (Lepizig: Leipnitz, ca. 1635). Engraving. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Oecon, 1722 p.

Courtiers crowd around a table groaning with gold and silver vessels in this miniature from a Book of Hours, a Christian devotional text. The duc de Berry, wearing a voluminous cloak of royal blue patterned with stylized pomegranates and sunbursts, sits behind the table, in conversation with a courtier to his right. In the foreground, a man dressed in green stands facing the duke. With his right hand, he suspends a knife over a platter of small fowl. A white cloth drapes over his left shoulder, while a black bag slung from his waist carries another knife and other tools. He is most likely the écuyer tranchant, or squire-carver, a highly trained servant responsible for carving and serving at a banquet.

Above: Limbourg brothers (Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg), January, from Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, 1413–89. Ink on vellum. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Courtiers crowd around a table groaning with gold and silver vessels in this miniature from a Book of Hours, a Christian devotional text. The duc de Berry, wearing a voluminous cloak of royal blue patterned with stylized pomegranates and sunbursts, sits behind the table, in conversation with a courtier to his right. In the foreground, a man dressed in green stands facing the duke. With his right hand, he suspends a knife over a platter of small fowl. A white cloth drapes over his left shoulder, while a black bag slung from his waist carries another knife and other tools. He is most likely the écuyer tranchant, or squire-carver, a highly trained servant responsible for carving and serving at a banquet.

Left: Limbourg brothers (Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg), January, from Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, 1413–89. Ink on vellum. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

An intimate supper for four is taking place in an airy hall. The carver stands at the front of the round table, holding a knife and fork, poised for action, about to cut into the turkey pie at the center of the table—or perhaps there are more dishes arriving from the kitchen, just visible in the upper right corner. A drinks cooler in the left foreground holds bottles and an extra glass.

Right: Johann Georg Pasch, frontispiece, from Neu vermehrtes vollständiges Trincier-Büch (Naumburg: Martin Müller, 1665). Engraving. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB/265717.

An intimate supper for four is taking place in an airy hall. The carver stands at the front of the round table, holding a knife and fork, poised for action, about to cut into the turkey pie at the center of the table—or perhaps there are more dishes arriving from the kitchen, just visible in the upper right corner. A drinks cooler in the left foreground holds bottles and an extra glass.

Above: Johann Georg Pasch, frontispiece, from Neu vermehrtes vollständiges Trincier-Büch (Naumburg: Martin Müller, 1665). Engraving. Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB/265717.

The 1665 Neu-Erfundenes Trenchir-Buch depicts two couples seated at a table in a pastoral landscape. A trinciante stands before the table holding a joint of beef or a fowl aloft on a fork, his knife poised to slice in aria. A shepherd can be seen in the background, his sheep grazing placidly despite the rather formal picnic.

Above: Andreas Klett, frontispiece, from Neu-Erfundenes Trenchir-Buch ([Leipzig], 1665). Engraving. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

The 1665 Neu-Erfundenes Trenchir-Buch depicts two couples seated at a table in a pastoral landscape. A trinciante stands before the table holding a joint of beef or a fowl aloft on a fork, his knife poised to slice in aria. A shepherd can be seen in the background, his sheep grazing placidly despite the rather formal picnic.

Left: Andreas Klett, frontispiece, from Neu-Erfundenes Trenchir-Buch ([Leipzig], 1665). Engraving. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Above: Andreas Klett, frontispiece, from Neues Trenchir-und Plicatur Büchlein, page 5 (Nuremberg: Leonhard Loschge, 1677). Engraving. Staats- und Univeritätsbibliothek Dresden, 2007 8 037757.

*A Carver in his Wunderkammer* In the frontispiece for this manual, a man—presumably the author and carver Andreas Klett—stands before a table covered with spiral-carved fruits. Animal carcasses, including fowl and quadrupeds, hang on either side from a pole that traverses the room, while fish and eels lie on a shelf to the left. The scene is reminiscent of catalogue frontispieces for cabinets of curiosities (Kunst- und Wunderkammern), which depict collectors surrounded by the rare and precious objects they have amassed. This clever evocation of the carver is also humorous—the book this image introduces will instruct the reader in the butchery of his collection.

This maiolica plate features a central section depicting a large cleaver marked with the initial “F.” Might this have belonged to a trinciante or a butcher? Who else would want their initial depicted on the blade of a knife? The utensil is held by a hand dressed with three distinct layers of clothing: a tight-fitting shirt in yellow, a looser white linen shift, and a frilled ruff-like top layer, which suggests that the person to whom the hand (and therefore the knife) belongs is of high status. On the reverse, a blue-and-orange pattern in “petal-back” style links it with related plates from Deruta. An initial “C” painted on the foot is similar to works painted by the same hand with different initials, suggesting that it is not the mark of a painter or workshop. The shape of the knife is similar to one of the knives portrayed by Bartolomeo Scappi in his 1570 cookbook.

This maiolica plate features a central section depicting a large cleaver marked with the initial “F.” Might this have belonged to a trinciante or a butcher? Who else would want their initial depicted on the blade of a knife? The utensil is held by a hand dressed with three distinct layers of clothing: a tight-fitting shirt in yellow, a looser white linen shift, and a frilled ruff-like top layer, which suggests that the person to whom the hand (and therefore the knife) belongs is of high status. On the reverse, a blue-and-orange pattern in “petal-back” style links it with related plates from Deruta. An initial “C” painted on the foot is similar to works painted by the same hand with different initials, suggesting that it is not the mark of a painter or workshop. The shape of the knife is similar to one of the knives portrayed by Bartolomeo Scappi in his 1570 cookbook.

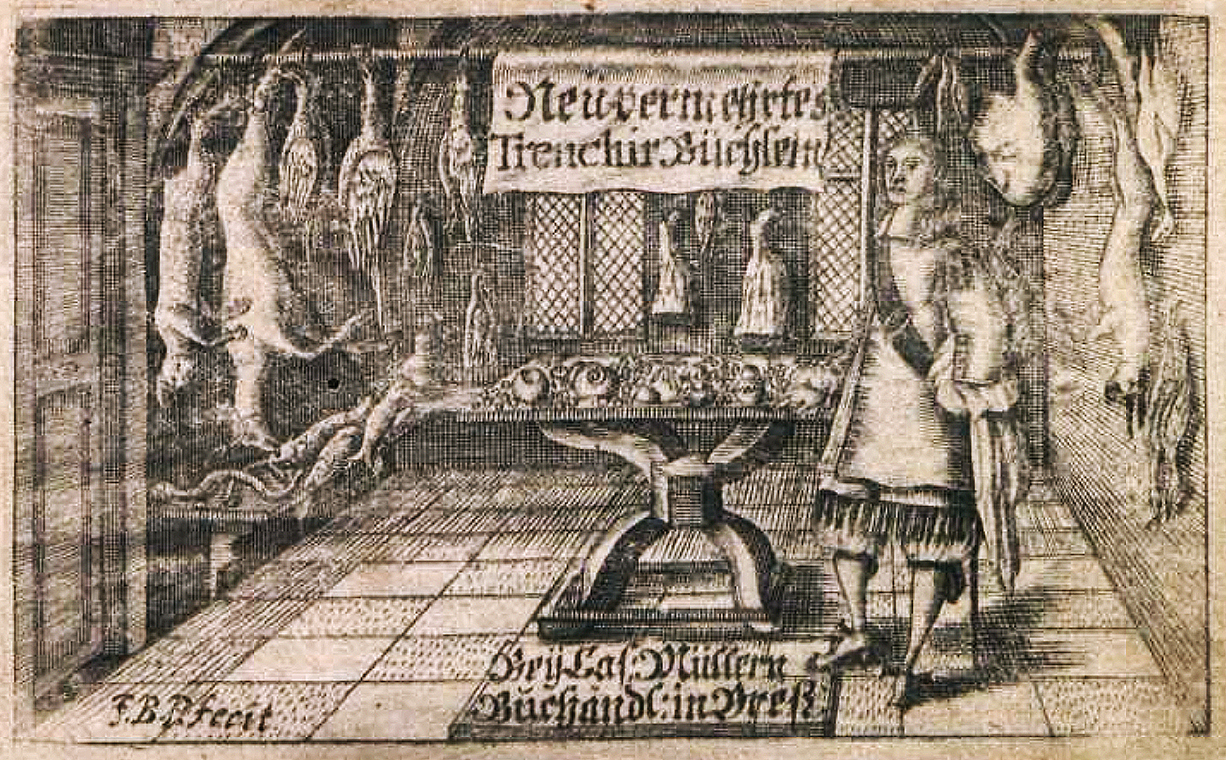

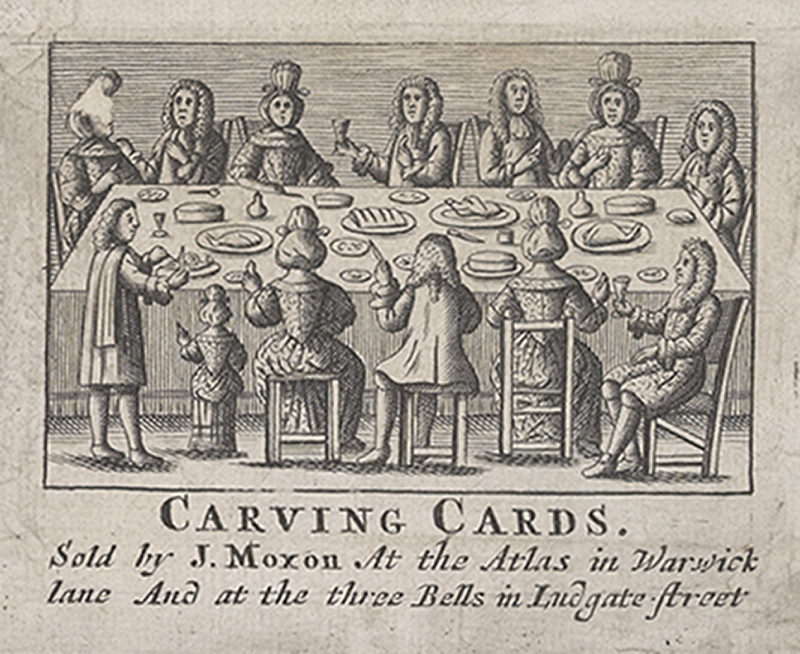

*Carving Cards* This image is found on the wrapper for a deck of fifty-three playing cards brought out in London, likely in 1677, by James Moxon, member of the Royal Society. Moxon was also a purveyor of globes, maps, scientific and mathematical instruments, books, and other decks of cards. Each of the four suits comprises a kind of food: The spades are “baked meats,” architecturally shaped meat pies with fillings such as goose, tongue, potato or hare; the hearts are “beasts,” such as loin of veal or shoulder of mutton; the diamonds are “fowl” such as goose, woodcock and duck; and the clubs are fish such as trout and mackerel. The images are diagrams derived from the carving manuals by Giegher, Harsdörffer, and others visible in the exhibition. The cards show the viewer where to make the cuts on the meats, fowl, and fish, and how to shape the pies. By the end of the seventeenth century, carving skills were included in the growing number of cookbooks and related household manuals explicitly addressed to women such as the “genteel house-keeper” named in the title.

A short pamphlet published with the cards provided verbal instructions on how to carve and serve meats, including the sauces to offer with them (although without recipes) similar to those found in contemporary cookbooks. Good carving, the narrator argues, teaches its practitioners anatomy and math: “the Dissection of Parts, the Scituation of Joynts and Ligaments, and the true position of the (at least) eminent Muscles. Nor does it shut out the most excellent Sciences of Arithmetick and Geometry.” If good carving improves a dish, its opposite, the “disorderly mangling a Joynt or Dish of good meat, is not only an unthrifty wasting of it, but sometimes the cause of loathing, to a curious Observers or a weak stomack.” Though the title spells out the audience for the cards, it is not clear exactly how–or if–they would have been used in an instructional capacity. A hint is provided in the text. The narrator explains that the book will demonstrate carving “on curious engraven Cuts, accommodated to Playing Cards, since they are full as intelligible as if they were Printed in the Book, and more easie to peruse when you read upon each Card: because you may hold the Card in your hand while you are reading the Rules relating to it, though it may be for many leaves, without being troubled to turn backward or forward to the Figure.”

Above: Wrapper, from The Genteel House-Keepers Pastime, Or, The Mode of Carving at the Table Represented in a Pack of Playing Cards. Printed and sold by J. Moxon, London, 1693. Engraving. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, UvL50 693G.

Above: Wrapper, from The Genteel House-Keepers Pastime, Or, The Mode of Carving at the Table Represented in a Pack of Playing Cards. Printed and sold by J. Moxon, London, 1693. Engraving. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, UvL50 693G.

A short pamphlet published with the cards provided verbal instructions on how to carve and serve meats, including the sauces to offer with them (although without recipes) similar to those found in contemporary cookbooks. Good carving, the narrator argues, teaches its practitioners anatomy and math: “the Dissection of Parts, the Scituation of Joynts and Ligaments, and the true position of the (at least) eminent Muscles. Nor does it shut out the most excellent Sciences of Arithmetick and Geometry.” If good carving improves a dish, its opposite, the “disorderly mangling a Joynt or Dish of good meat, is not only an unthrifty wasting of it, but sometimes the cause of loathing, to a curious Observers or a weak stomack.” Though the title spells out the audience for the cards, it is not clear exactly how–or if–they would have been used in an instructional capacity. A hint is provided in the text. The narrator explains that the book will demonstrate carving “on curious engraven Cuts, accommodated to Playing Cards, since they are full as intelligible as if they were Printed in the Book, and more easie to peruse when you read upon each Card: because you may hold the Card in your hand while you are reading the Rules relating to it, though it may be for many leaves, without being troubled to turn backward or forward to the Figure.”

* * *

* * *

*The Carving Table* This interactive feature explores Moxon’s deck of cards, inviting visitors to learn about early modern European foodways and their illuminating, often surprising and far-flung, connections to dining practices in our own time. This interactive is best viewed on desktop.

Click image to view the interactive

Click image to view the interactive