*Books as Objects*

*Books as Objects*

s you peruse this site, you will see numerous editions or copies of closely related books, often bearing similar names. These multiples enable us to compare many pages with related content, demonstrating both the reproduction and dissemination of particular diagrams. Even very similar books take on individual identities as they move through time and space. Books convey meaning through their content, but also through their physical attributes such as dimensions, materials, typography, color, organization, and production techniques. Owners often personalize their books with stamps, inscriptions, marginalia, and repairs or new bindings, all of which contribute to a book’s unique biography.

s you peruse this site, you will see numerous editions or copies of closely related books, often bearing similar names. These multiples enable us to compare many pages with related content, demonstrating both the reproduction and dissemination of particular diagrams. Even very similar books take on individual identities as they move through time and space. Books convey meaning through their content, but also through their physical attributes such as dimensions, materials, typography, color, organization, and production techniques. Owners often personalize their books with stamps, inscriptions, marginalia, and repairs or new bindings, all of which contribute to a book’s unique biography.

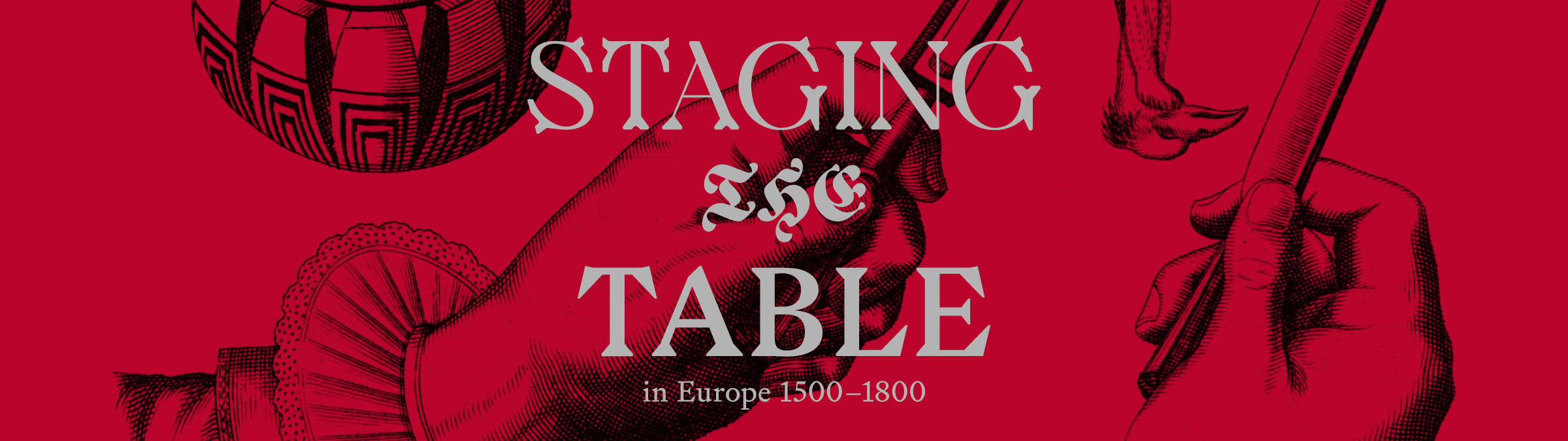

There are several physical features that distinguish one book from another. Many are printed in horizontal or landscape format and flexibly bound with paper or vellum, allowing them to lie open so that readers can view their contents while using both hands to carve or fold. Oblong quartos, as they are called, were also the preferred format for other instructional texts such as musical scores, calligraphy and penmanship manuals, and patterns for tailors. German printers employed a wide variety of fonts within a single publication, reserving black letter type for German words, while using roman or italic fonts for words with Latin origins. The use of mixed type in the graphic design of this website is inspired by this seventeenth-century phenomenon.

Above: Andreas Brettschneider, title page, from Giacomo Procacchi, Trincier Oder Vorlege-Buch (Leipzig: Henning Gross the Younger, 1624). Engraving. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX885.P96 1624.

Above: Andreas Brettschneider, title page, from Giacomo Procacchi, Trincier Oder Vorlege-Buch (Leipzig: Henning Gross the Younger, 1624). Engraving. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX885.P96 1624.

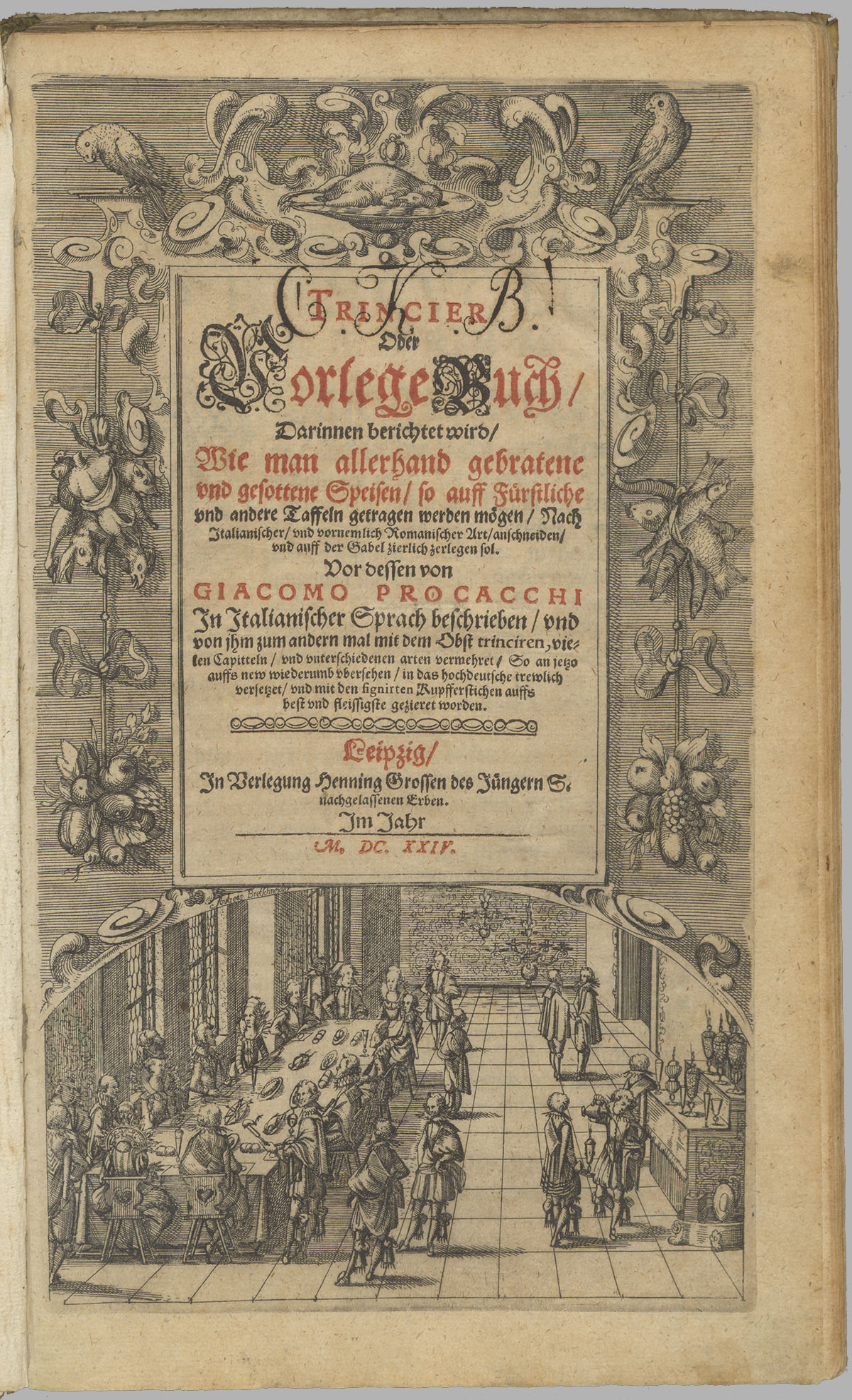

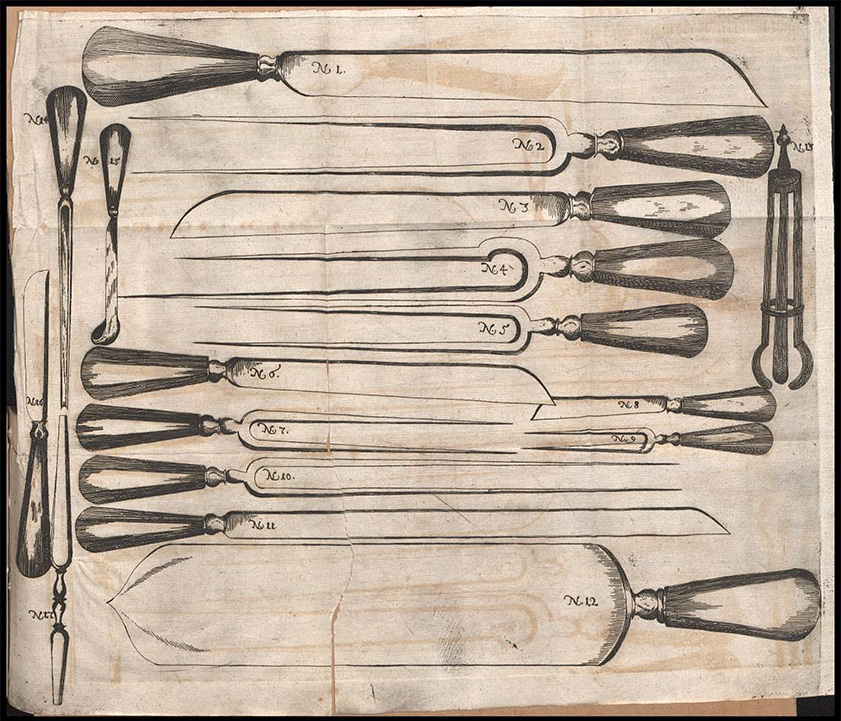

*Tools in Print* Complete sets of carver’s knives from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries are very rare, but prints and paintings show us what they looked like. Starting with Giovanni Francesco Colle’s Refugio del povero gentilhuomo in 1520, illustrated manuals for carvers depict an array of knives and forks in graduated proportions, clearly intended to represent the ideal arsenal for the well-endowed carver. Many of these images were printed on large sheets of paper and had to be tipped and folded into the books.

Right: Mattia Giegher, knives and forks, from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1639). Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1940, 40.84.

*Tools in Print* Complete sets of carver’s knives from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries are very rare, but prints and paintings show us what they looked like. Starting with Giovanni Francesco Colle’s Refugio del povero gentilhuomo in 1520, illustrated manuals for carvers depict an array of knives and forks in graduated proportions, clearly intended to represent the ideal arsenal for the well-endowed carver. Many of these images were printed on large sheets of paper and had to be tipped and folded into the books.

Above: Mattia Giegher, knives and forks, from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1639). Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1940, 40.84.

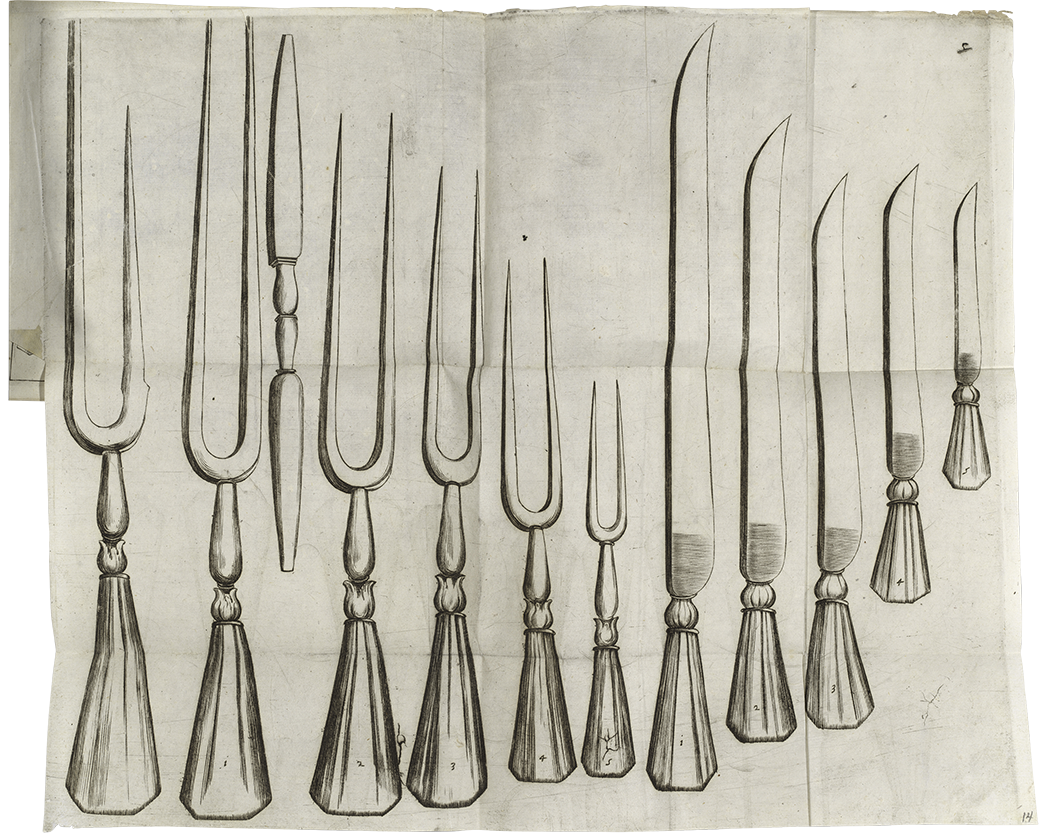

The Refugio features the first printed illustration of carving tools. In this book, written by a trinciante, the term “carving in the air’’ appears for the first time. In keeping with other instructional texts ostensibly authored by practitioners asked to record their knowledge, Giovanni Francesco Colle indicates that his employer, Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, requested that he write “this simple and incongruous little work” about “skillful and courtly carving.” The tools are labeled according to their function—fruit, meat, cake, and dismembering or boning. The reversed n in the word carne (meat) is a mistake that was evidently not worth a revision.

Above: Giovanni Francesco Colle, carving tools, from Refugio over ammonitorio de gentilhuomo (1532), A2v–3r. Woodcut. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX885 C650 1532.

The Refugio features the first printed illustration of carving tools. In this book, written by a trinciante, the term “carving in the air’’ appears for the first time. In keeping with other instructional texts ostensibly authored by practitioners asked to record their knowledge, Giovanni Francesco Colle indicates that his employer, Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, requested that he write “this simple and incongruous little work” about “skillful and courtly carving.” The tools are labeled according to their function—fruit, meat, cake, and dismembering or boning. The reversed n in the word carne (meat) is a mistake that was evidently not worth a revision.

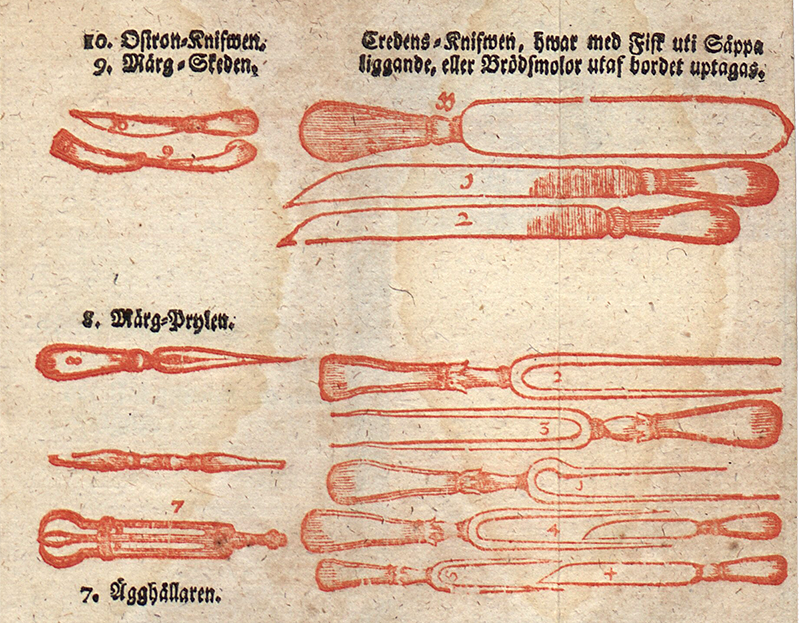

This small Swedish carving manual, probably adapted from German sources, includes diagrams related to many of the images that ultimately derive from Mattia Giegher’s Tre Trattati. A foldout depicts the carver’s arsenal in vivid red ink, showing the different-sized knives required to guarantee proper execution of the various techniques, including an egg holder, oyster knife, and marrow scoop.

Right: Knives and forks, from En mycket nyttig och förbättrad trenchier-bok . . . (Västerås: Johann Laurens Horrn, 1759). Conjuring Arts Research Center, New York.

This small Swedish carving manual, probably adapted from German sources, includes diagrams related to many of the images that ultimately derive from Mattia Giegher’s Tre Trattati. A foldout depicts the carver’s arsenal in vivid red ink, showing the different-sized knives required to guarantee proper execution of the various techniques, including an egg holder, oyster knife, and marrow scoop.

Above: Knives and forks, from En mycket nyttig och förbättrad trenchier-bok . . . (Västerås: Johann Laurens Horrn, 1759). Conjuring Arts Research Center, New York.

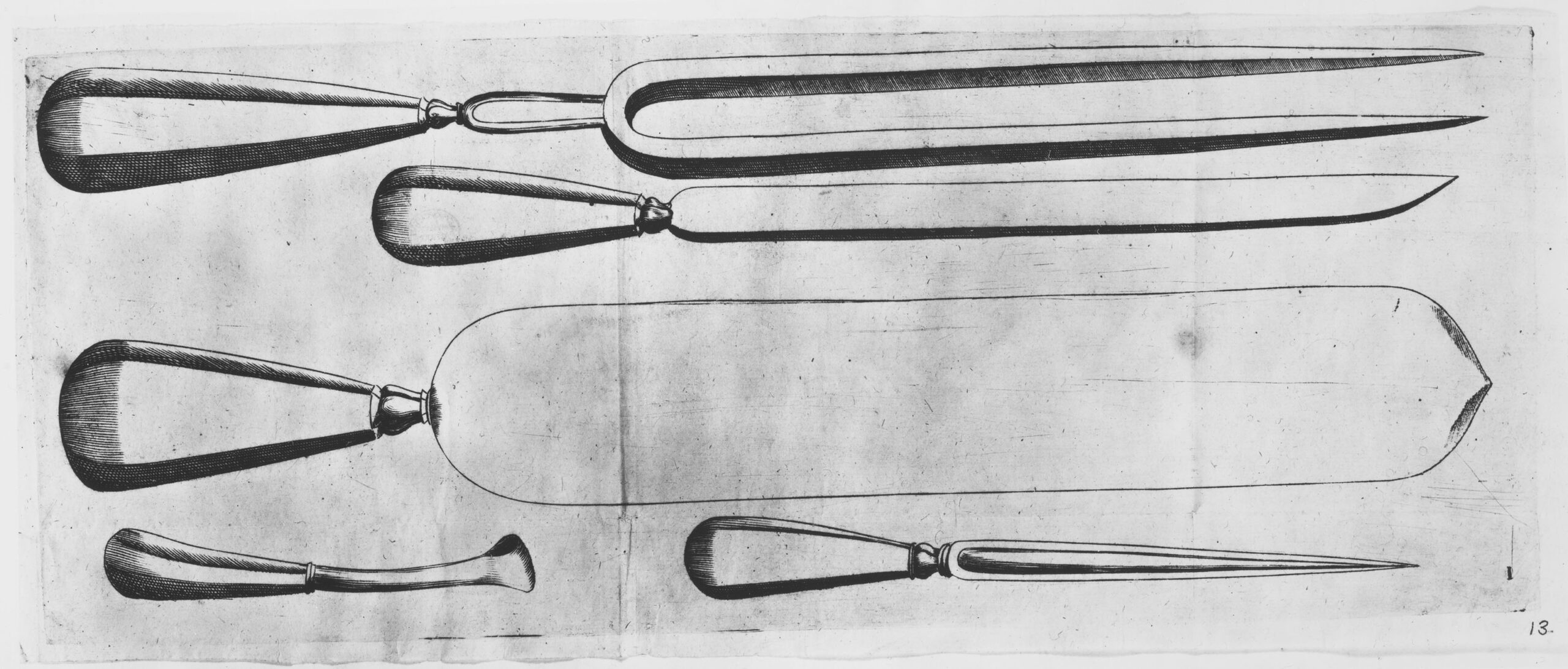

Mattia Giegher’s carving manual, Il Trattato del Trinciante (The Treatise of the Carver), one of three treatises published together in 1629, was first brought out in 1621 as a separate pamphlet. The images of sets of knives, published as foldouts to accommodate the form of the tools, indicate that a variety of sizes and blade shapes were desirable to carry out the instructions provided.

Above: Mattia Giegher, knives, presentation knife, fork, skewer, and scoop, from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1639). Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1940, 40.84.

Mattia Giegher’s carving manual, Il Trattato del Trinciante (The Treatise of the Carver), one of three treatises published together in 1629, was first brought out in 1621 as a separate pamphlet. The images of sets of knives, published as foldouts to accommodate the form of the tools, indicate that a variety of sizes and blade shapes were desirable to carry out the instructions provided.

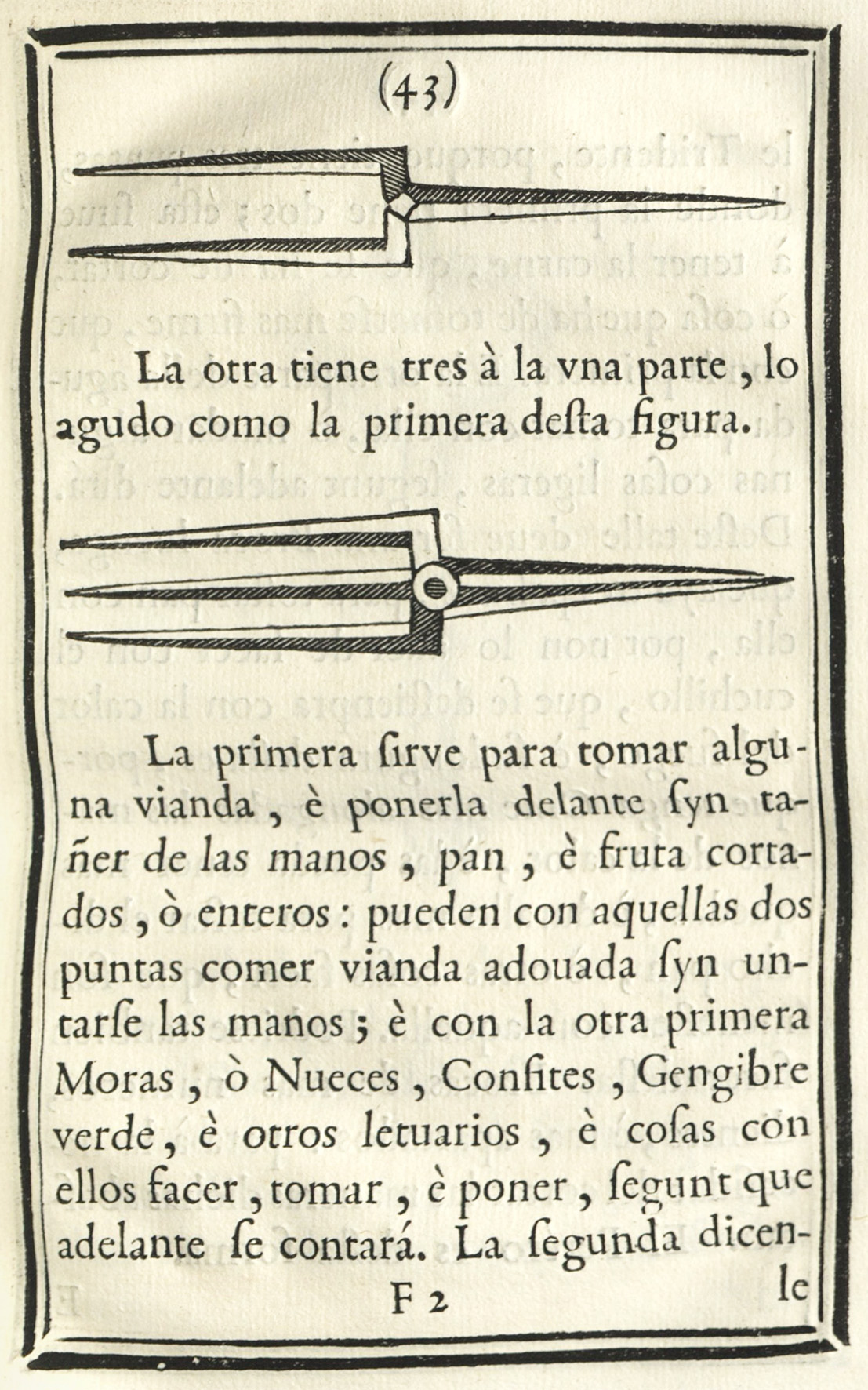

This illustration comes from the first printed version of the manuscript treatise known today as Arte Cisoria, written in 1423 but not printed until the eighteenth century. Enrique de Villena was carver at the court of Alfonso I of Aragon. The text details the variety of knives and forks the carver should have in his arsenal: five knives of iron and steel, each with specific dimensions and adapted for particular use, and two forks of gold and silver to spear the food and hold it in place while cutting. Villena reports that Italian, German, and English knife handles were often made of ivory inlaid with gold and silver, while the Moors used small knives since they ate stewed and boneless meats. In Castile, the knives were coarse and heavy, with gilded and fluted handles.

Right: Enrique De Aragón Villena, two forks, from Arte Cisoria . . . , page 43 (Madrid: A. Marin, 1766). Woodcut. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RBS21.

This illustration comes from the first printed version of the manuscript treatise known today as Arte Cisoria, written in 1423 but not printed until the eighteenth century. Enrique de Villena was carver at the court of Alfonso I of Aragon. The text details the variety of knives and forks the carver should have in his arsenal: five knives of iron and steel, each with specific dimensions and adapted for particular use, and two forks of gold and silver to spear the food and hold it in place while cutting. Villena reports that Italian, German, and English knife handles were often made of ivory inlaid with gold and silver, while the Moors used small knives since they ate stewed and boneless meats. In Castile, the knives were coarse and heavy, with gilded and fluted handles.

Above: Enrique De Aragón Villena, two forks, from Arte Cisoria . . . , page 43 (Madrid: A. Marin, 1766). Woodcut. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RBS21.

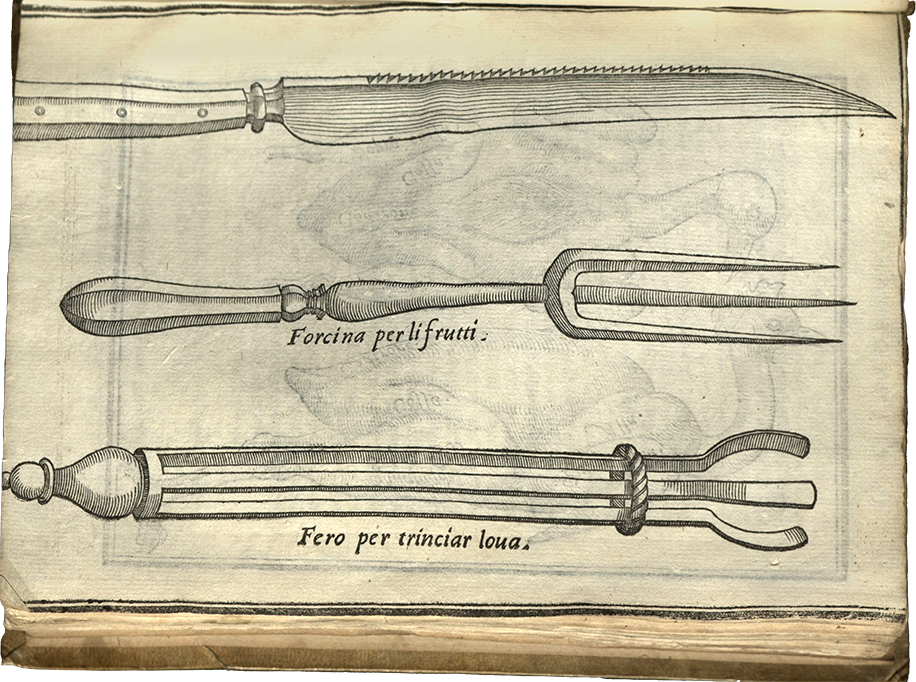

This book records the carving practices of Vincenzo Cervio, carver to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in Rome, a noted collector and patron of the arts. The fame of both Cervio and his patron led to the publication of Il Trinciante, which includes instructions on how to clean and sharpen knives, how the carver should dress and act, the characteristics of knives from different countries, and how to carve various meats, fowl, fish, and fruit.

Above: Vincenzo Cervio, “Knife, fruit fork, and egg holder,” from Il Trinciante . . . (Rome: Gabbia, 1593). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1593 (Cervio, V. Trinciante).

This book records the carving practices of Vincenzo Cervio, carver to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in Rome, a noted collector and patron of the arts. The fame of both Cervio and his patron led to the publication of Il Trinciante, which includes instructions on how to clean and sharpen knives, how the carver should dress and act, the characteristics of knives from different countries, and how to carve various meats, fowl, fish, and fruit.

Left: Vincenzo Cervio, “Knife, fruit fork, and egg holder,” from Il Trinciante . . . (Rome: Gabbia, 1593). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1593 (Cervio, V. Trinciante).

This foldout depicts a variety of blade shapes and sizes, as well as forks. Among the items included are broad, flat serving or presentation knives like the two Hans Sumersperger examples included in the section on Tools of the Trade, smaller fruit knives, a marrow scoop, and the three-pronged egg holder that appears first in Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante of 1581.

Right: Johann Georg Pasch, knives, from Neu vermehrtes vollständiges Trincier-Büch . . . (Naumburg: Martin Müller, 1665). Engraving. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB/265717.

This foldout depicts a variety of blade shapes and sizes, as well as forks. Among the items included are broad, flat serving or presentation knives like the two Hans Sumersperger examples included in the section on Tools of the Trade, smaller fruit knives, a marrow scoop, and the three-pronged egg holder that appears first in Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante of 1581.

*Browsing the Books* Click the image to explore selections from seventeenth-century Italian, German, and French illustrated books and get a taste of the rich visual world they evoke.

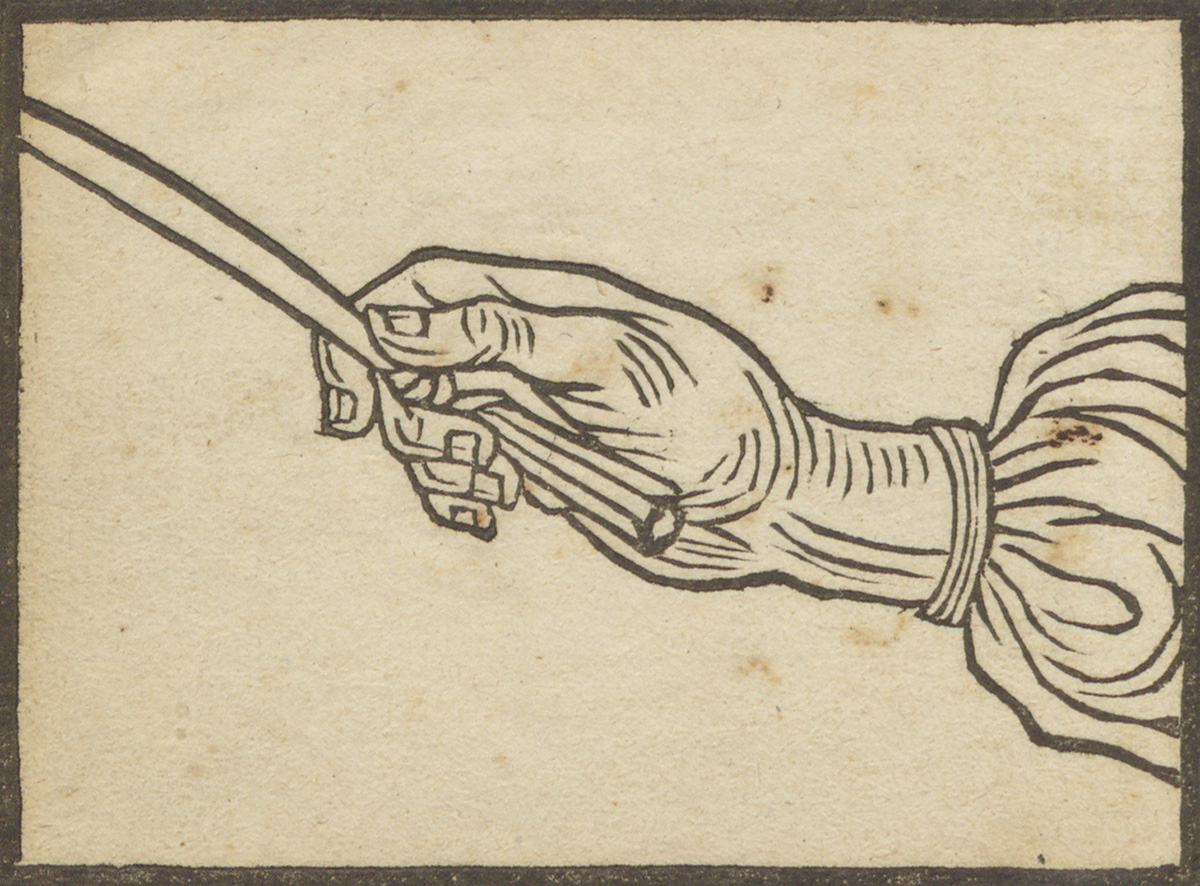

Above: From De Sectione Mensaria, 17th century. Woodcut. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX635.D4 1600z c.1.

*Browsing the Books* Click the image to explore selections from seventeenth-century Italian, German, and French illustrated books and get a taste of the rich visual world they evoke.

Left: From De Sectione Mensaria, 17th century. Woodcut. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX635.D4 1600z c.1.