*Carving by the Book*

*Carving by the Book*

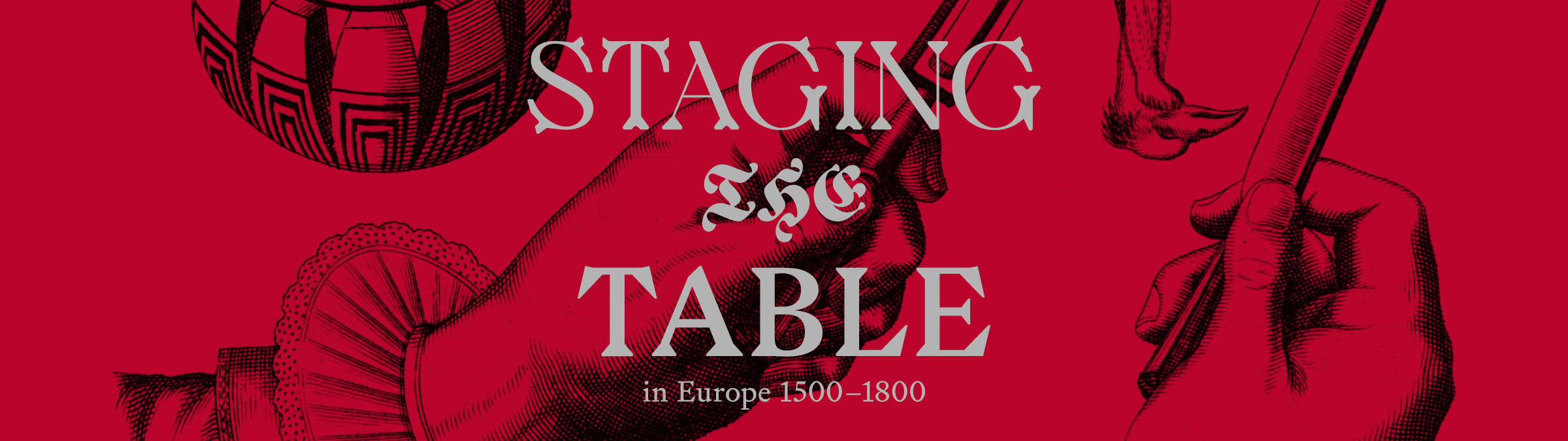

he carver’s art has been recognized since antiquity, as documented in the passage on the homepage from first-century CE Roman author Juvenal, but texts demonstrating how to carve survive only from the late Middle Ages. For example, Wynkyn de Worde’s Boke of Keruynge from 1508 provides detailed instructions for dissecting and serving a variety of animals from field, forest, stream, and pasture. Each dish demanded a particular verb for its undoing: the carver must break a deer, rear a goose, lift a swan, spoil a hen, fruche a chicken, unbrace a mallard, unlace a coney, display a crane, disfigure a peacock, allay a pheasant, wing a partridge, mince a plover, thigh a pigeon, tyre an egg, splat a pike, splay a bream, and so on.

he carver’s art has been recognized since antiquity, as documented in the passage on the homepage from first-century CE Roman author Juvenal, but texts demonstrating how to carve survive only from the late Middle Ages. For example, Wynkyn de Worde’s Boke of Keruynge from 1508 provides detailed instructions for dissecting and serving a variety of animals from field, forest, stream, and pasture. Each dish demanded a particular verb for its undoing: the carver must break a deer, rear a goose, lift a swan, spoil a hen, fruche a chicken, unbrace a mallard, unlace a coney, display a crane, disfigure a peacock, allay a pheasant, wing a partridge, mince a plover, thigh a pigeon, tyre an egg, splat a pike, splay a bream, and so on.

Above: Wynkyn de Worde, title page, from Here begynneth the boke of keruynge . . . (London: Wynkyn de Worde, 1508). Woodcut. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library, Sel.5.19.

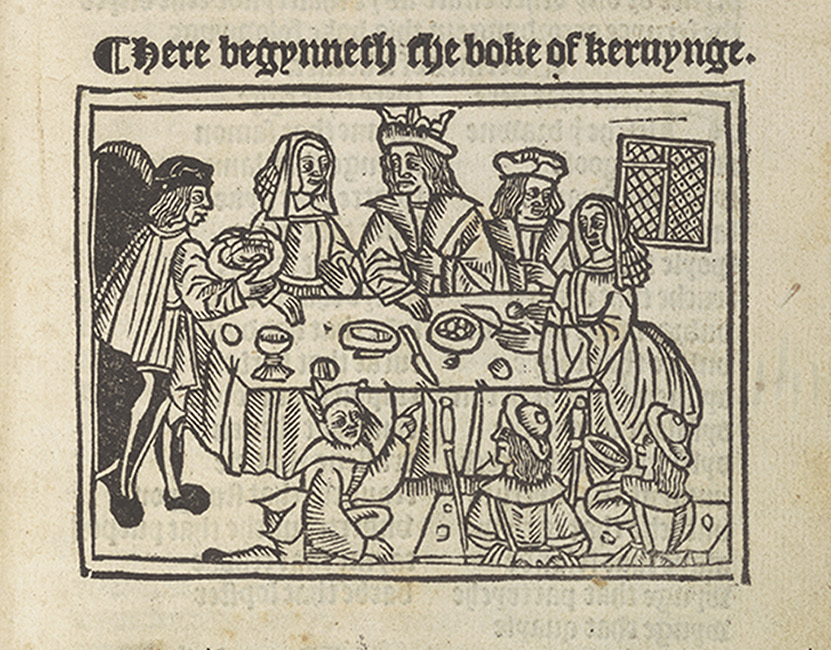

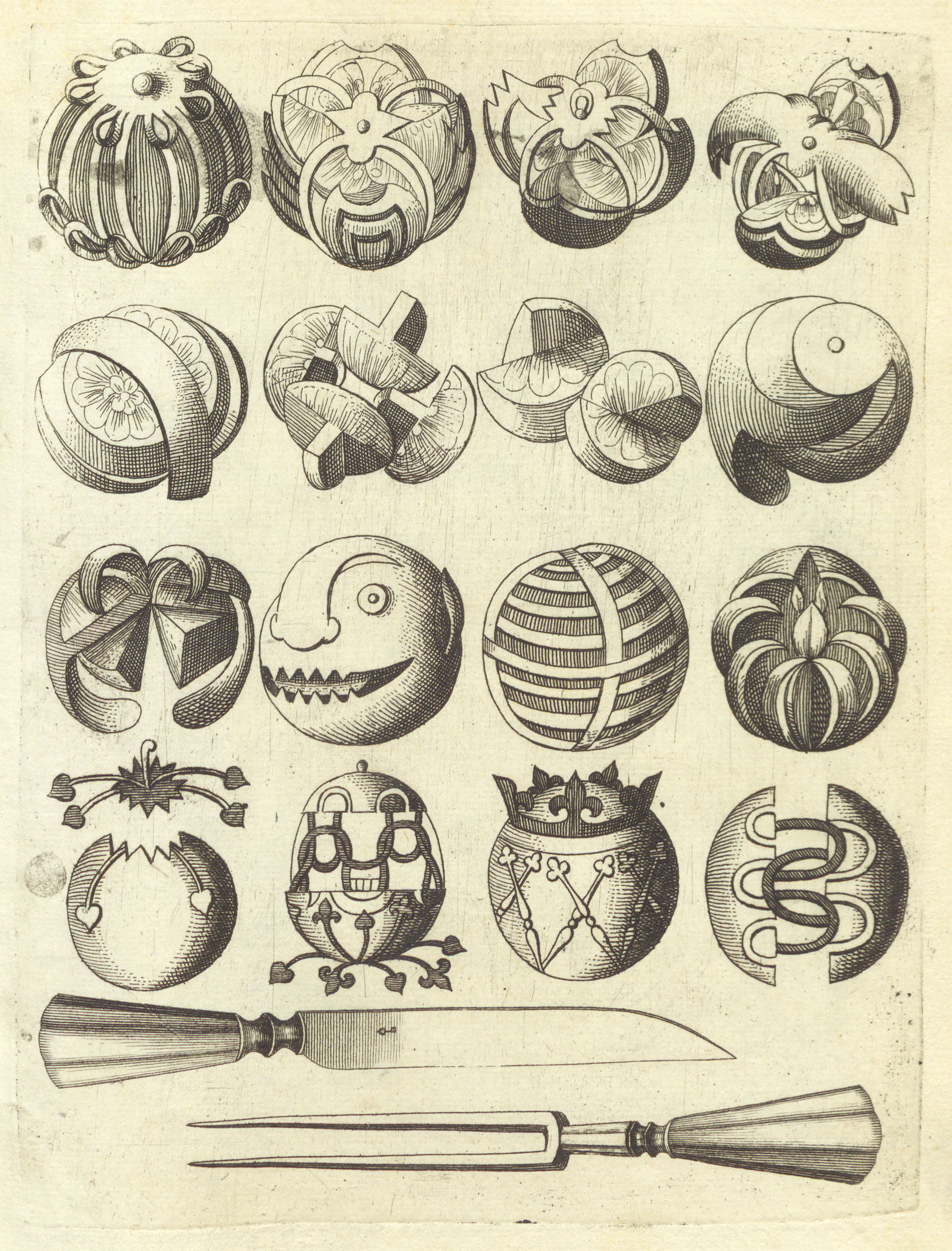

*Carving Methods* Starting in the sixteenth century, illustrated books provided pictures and diagrams explaining the methods of carving. The pages on view share a similar approach to the representation of these skills which were both technical and performative. Woodcuts and copperplate engravings instructed readers and users without limitations of language and were reproduced freely since copyright or other intellectual property laws were difficult to enforce, if they existed at all. Topics for illustration included carving tools, techniques for carving different cuts of meat, whole fowl, and fish; and methods for peeling fruit and fashioning it into animals and geometric forms.

Left: Vincenzo Cervio, from Il Trinciante . . . ampliato et a perfettione ridotto dal Cavalier Reale Fusoritto da Narni (Rome: Gabbia, 1593). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1593 (Cervio, V. Trinciante).

*Carving Methods* Starting in the sixteenth century, illustrated books provided pictures and diagrams explaining the methods of carving. The pages on view share a similar approach to the representation of these skills which were both technical and performative. Woodcuts and copperplate engravings instructed readers and users without limitations of language and were reproduced freely since copyright or other intellectual property laws were difficult to enforce, if they existed at all. Topics for illustration included carving tools, techniques for carving different cuts of meat, whole fowl, and fish; and methods for peeling fruit and fashioning it into animals and geometric forms.

Above: Vincenzo Cervio, from Il Trinciante . . . ampliato et a perfettione ridotto dal Cavalier Reale Fusoritto da Narni (Rome: Gabbia, 1593). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1593 (Cervio, V. Trinciante).

* * *

* * *

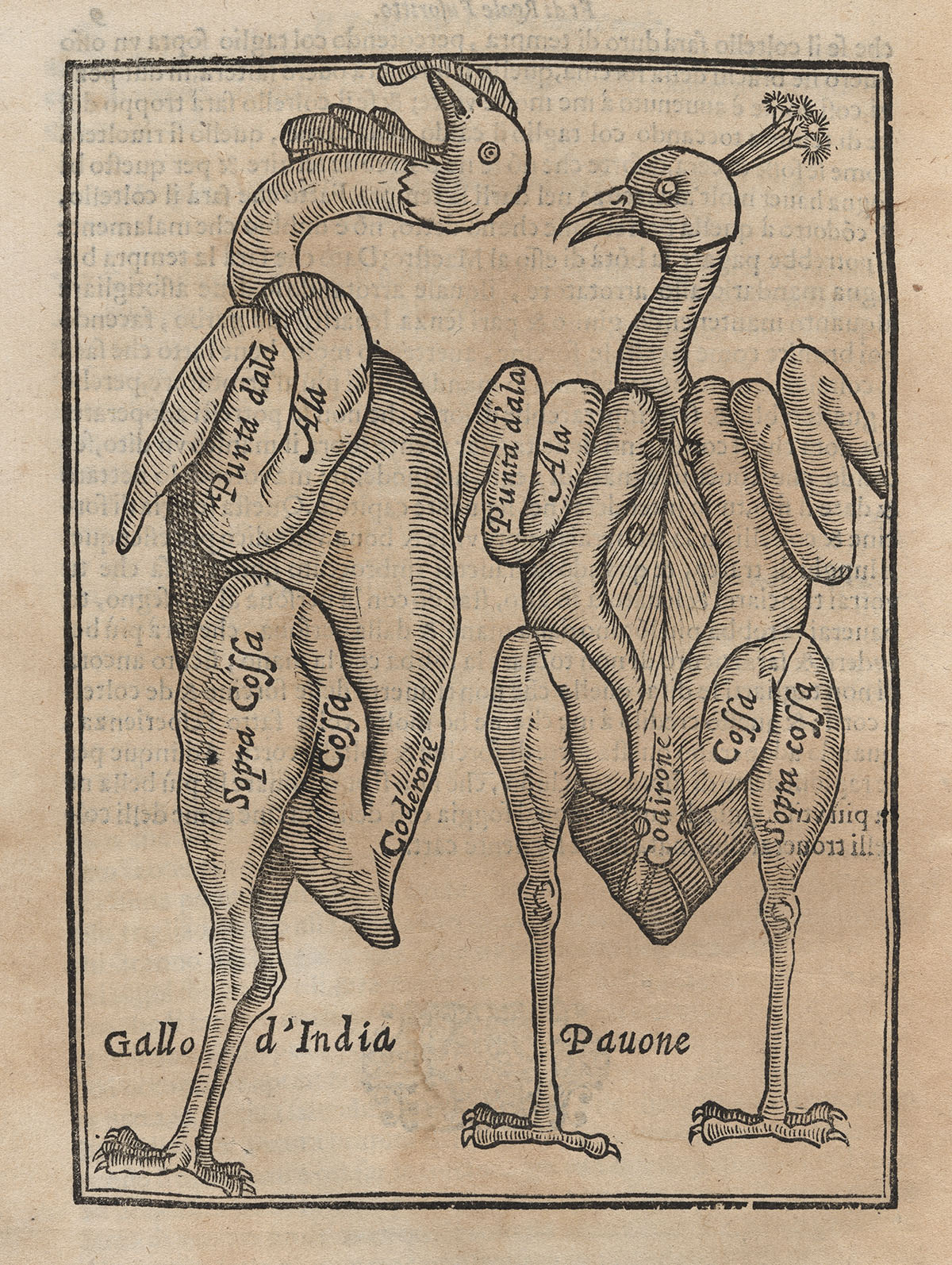

*Capon* This diminutive book with woodcut images of carving meats, fowl, and fruits is unsigned and undated. An introductory chapter, written in French “for the benefit of the traveler,” outlines the methods for carving and serving the foods illustrated, with detailed instructions for each. The capon is the first of the birds, shown together with the hand of the carver holding the knife. Some of the numbers indicating the order of attack have been added by hand, evidence that the book was used.

*Capon* This diminutive book with woodcut images of carving meats, fowl, and fruits is unsigned and undated. An introductory chapter, written in French “for the benefit of the traveler,” outlines the methods for carving and serving the foods illustrated, with detailed instructions for each. The capon is the first of the birds, shown together with the hand of the carver holding the knife. Some of the numbers indicating the order of attack have been added by hand, evidence that the book was used.

Above: Le chapon, from De Sectione Mensaria (17th century). Woodcut. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX635.D4 1600z c.1.

This Dutch carving manual, “The graceful carving of all dishes for the table,” follows the oblong format established by Mattia Giegher. The title page shows a diner sitting at a square table covered with various small dishes and one large pie garnished with a flower. To his left, a carver holds some kind of winged roast, poised to slice it in aria.

Above: Title page, from De Cierlijcke Voorsnydinge Aller Tafel Gerechten . . . (Amsterdam: Hieronymous Sweerts, ca. 1660). Engraving. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB.

This Dutch carving manual, “The graceful carving of all dishes for the table,” follows the oblong format established by Mattia Giegher. The title page shows a diner sitting at a square table covered with various small dishes and one large pie garnished with a flower. To his left, a carver holds some kind of winged roast, poised to slice it in aria.

Left: Title page, from De Cierlijcke Voorsnydinge Aller Tafel Gerechten . . . (Amsterdam: Hieronymous Sweerts, ca. 1660). Engraving. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB.

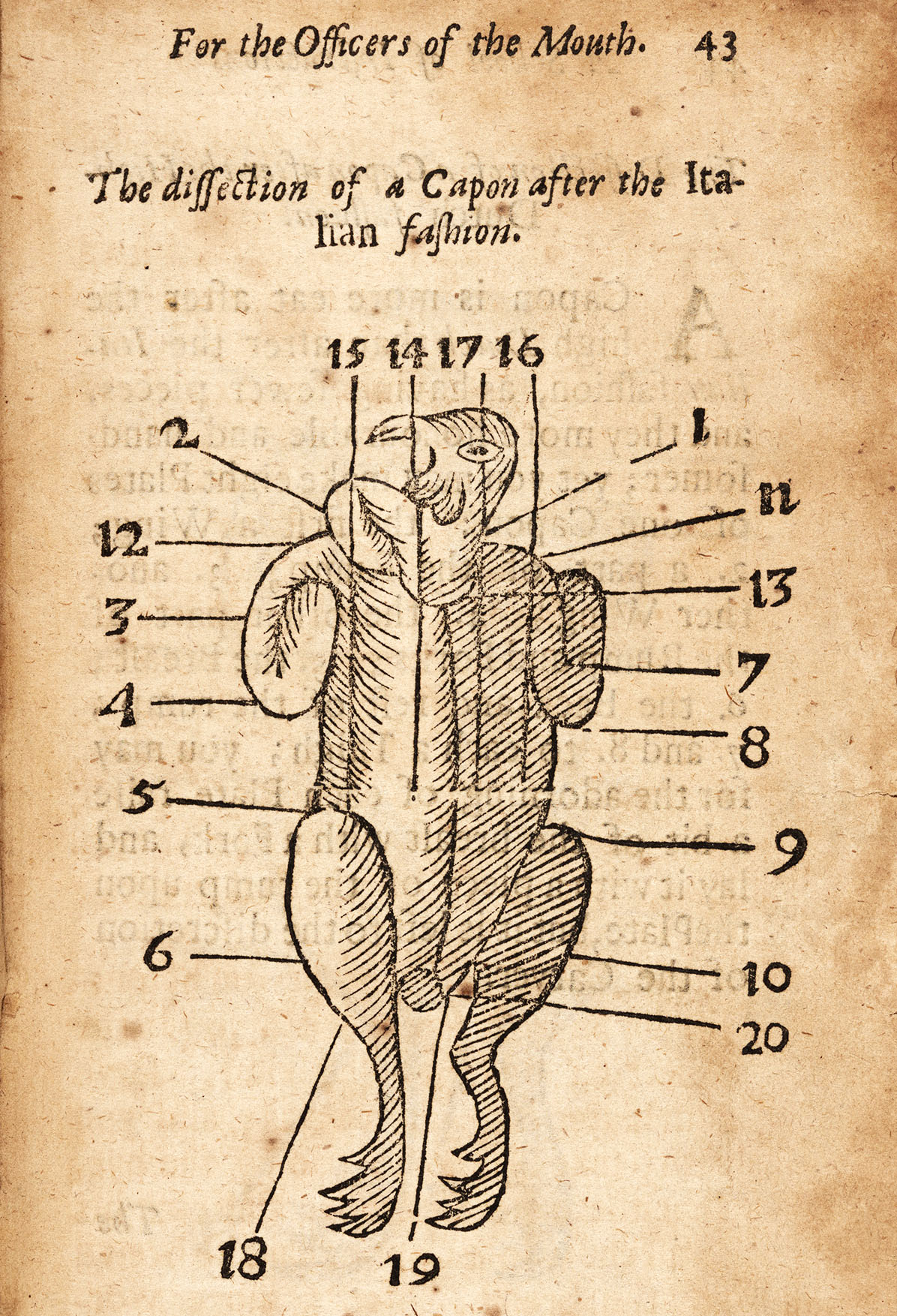

Italian carving techniques made their way to England by way of Giles Rose’s book, a translation of a 1662 French book with the same name. The page illustrating “the dissection of a Capon after the Italian fashion” presents a schematic diagram with a series of numbers corresponding to cuts. The text explains, “the Italians cut a Capon into a great many pieces; and those pieces are very small.”

Right: Anonymous, translated from French by Giles Rose, Capon, from A Perfect School of Instructions for the Officers of the Mouth . . . , page 43 (London: R. Bentley and M. Magnes, 1682). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, TX705.R79.

Italian carving techniques made their way to England by way of Giles Rose’s book, a translation of a 1662 French book with the same name. The page illustrating “the dissection of a Capon after the Italian fashion” presents a schematic diagram with a series of numbers corresponding to cuts. The text explains, “the Italians cut a Capon into a great many pieces; and those pieces are very small.”

Above: Anonymous, translated from French by Giles Rose, Capon, from A Perfect School of Instructions for the Officers of the Mouth . . . , page 43 (London: R. Bentley and M. Magnes, 1682). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, TX705.R79.

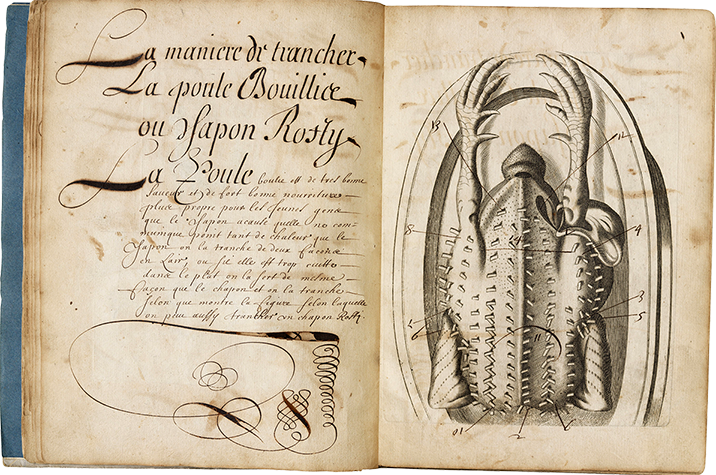

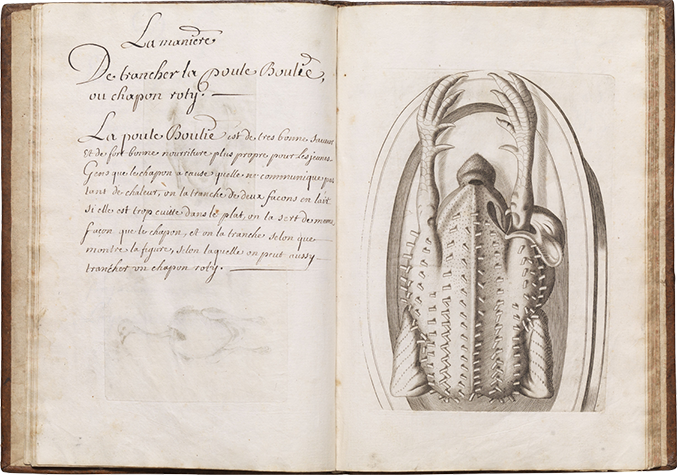

These two related books are hybrids, containing both printed images and handwritten text. They feature very similar engravings of cooked meats and fowl on platters, ready to be carved, along with diagrams of how to slice fruits. The text was copied onto loose sheets, while images were distributed as handouts and bound at a later date. Perhaps Jacques Vontet, a Swiss carving teacher, provided the master copy, while his pupils made notes on the engraved images and copied the explanations.

Each opening consists of a text page, with small variations in spelling and word choice, and a corresponding engraving. Under the heading “La maniere de trancher la poule Bouillie ou chapon rosty” (the manner of carving a boiled chicken or a roast capon), the following instructions are provided: “The boiled chicken has a very good taste and provides excellent nourishment more suited to young people than the capon due to the fact that it does not transmit as much heat as the capon. One carves it in two ways: in the air, or if it is too well-done, on the plate. It is done in the same way as the capon and it is carved according to the figure, according to which one may also carve the roast capon.” The mention of the relative heat of boiled and roasted chicken echoes regimen literature that credits foods with inherent qualities that make them more or less desirable based on the way they interact with an individual’s humoral constitution.

These two related books are hybrids, containing both printed images and handwritten text. They feature very similar engravings of cooked meats and fowl on platters, ready to be carved, along with diagrams of how to slice fruits. The text was copied onto loose sheets, while images were distributed as handouts and bound at a later date. Perhaps Jacques Vontet, a Swiss carving teacher, provided the master copy, while his pupils made notes on the engraved images and copied the explanations.

Each opening consists of a text page, with small variations in spelling and word choice, and a corresponding engraving. Under the heading “La maniere de trancher la poule Bouillie ou chapon rosty” (the manner of carving a boiled chicken or a roast capon), the following instructions are provided: “The boiled chicken has a very good taste and provides excellent nourishment more suited to young people than the capon due to the fact that it does not transmit as much heat as the capon. One carves it in two ways: in the air, or if it is too well-done, on the plate. It is done in the same way as the capon and it is carved according to the figure, according to which one may also carve the roast capon.” The mention of the relative heat of boiled and roasted chicken echoes regimen literature that credits foods with inherent qualities that make them more or less desirable based on the way they interact with an individual’s humoral constitution.

Above Top: Jacques Vontet, La Methode de trancher aloüetes Beqeufis, et ortolans avec toute sorte d’autres petits oyseaux (Lyon or Paris, ca. 1647–50). Iron-gall ink on paper. PY Rare Books. / Bottom: Jacques Vontet, No. 1 Au Lecteur Ce n’est pas sans Raison que les plus grands personnages de L’Europe se servent d’Escuyer tranchant (Lyon or Paris, ca. 1647–50). Manuscript. Ben Kinmont Bookseller.

* * *

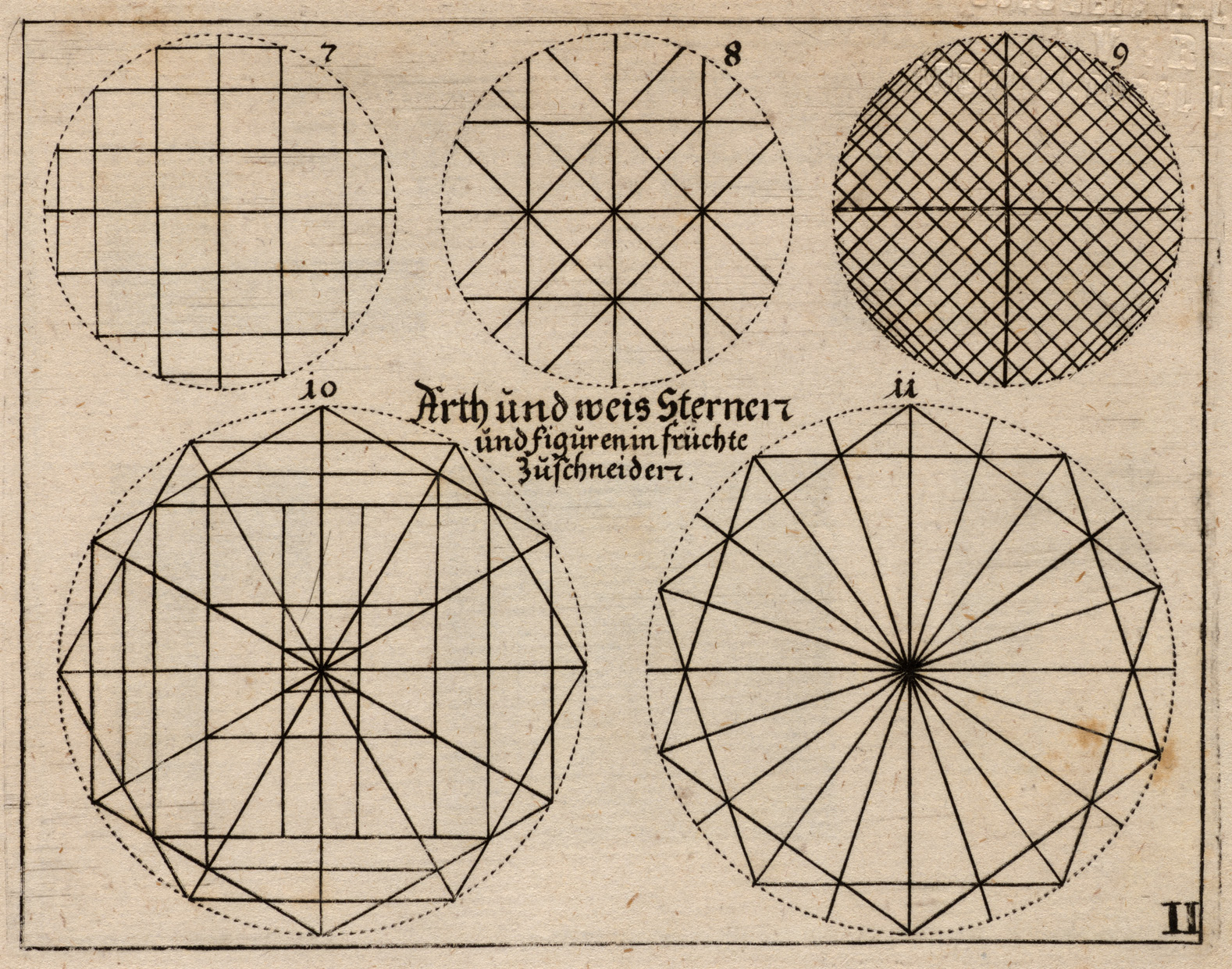

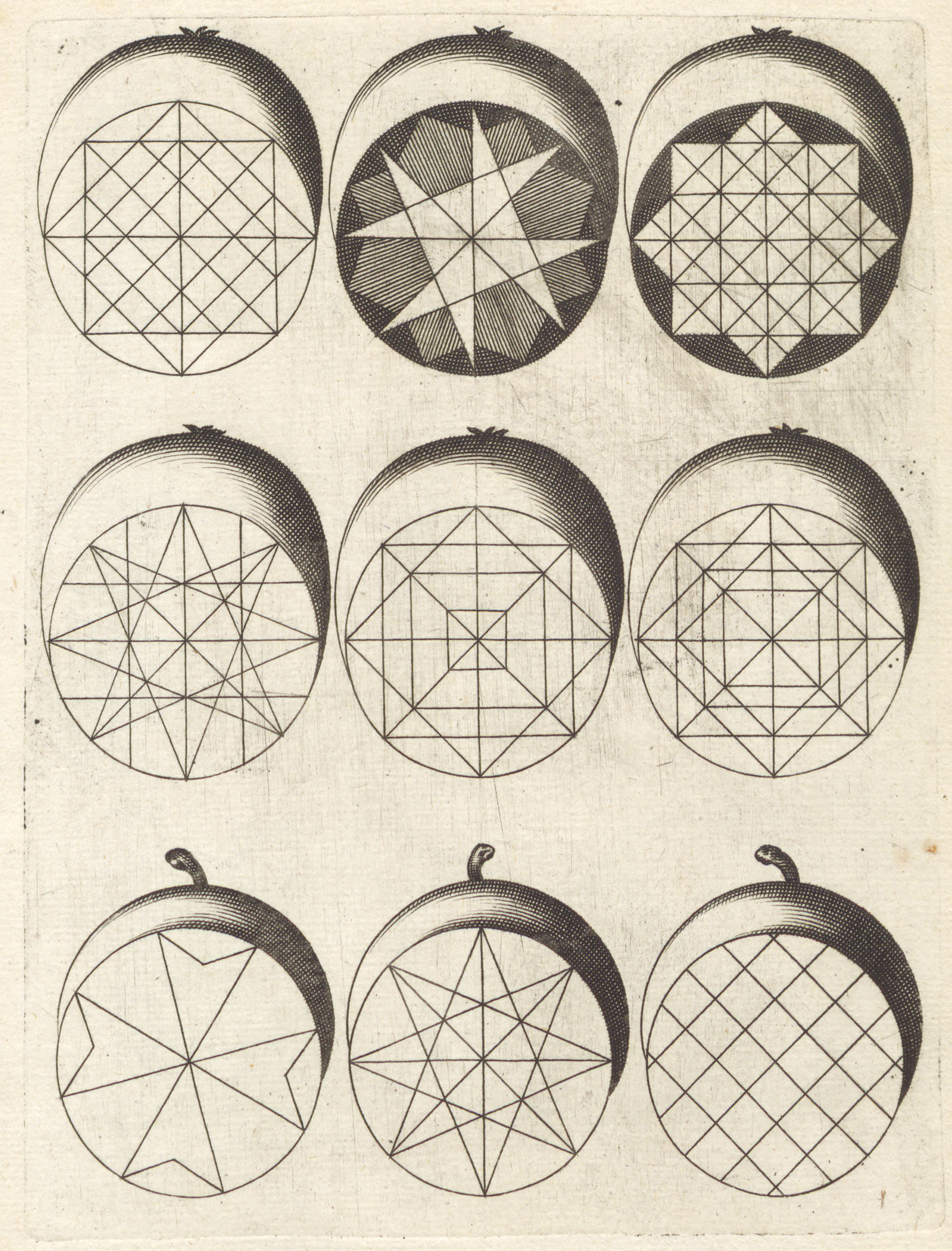

*Fruits* Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, a seventeenth-century literary figure, adapted Italian carving manuals for his learned German audience, among many other projects. These images introduce a subsection on the carving of fruit. Shown on top, a dais of solid rectangular blocks anchors a stout column draped with swags of skillfully carved fruits. Atop the column rest carving tools, a book, and two matched pairs of apples and pears. The meaning of this puzzling illustration is revealed by a rhyming verse on the following page: the knife is there to slice the fruit, not the hand nor the truth, since lies should melt into the air without effect and would not therefore need a knife. Several pages of introductory text follow, in which the author gives credit to “Mathematischer Wissenschaften” (mathematical sciences) as the wellspring of knowledge on how to slice and present fruits. Displayed below, a page from this section of the book demonstrates “the way to carve stars and figures of fruits,” inscribing geometric forms onto the abstracted fruit.

Right Top: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Anhang zu dem Andern theil, von früchten schneiden,” em>Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1665). Engraving. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, B641 H25. / Bottom: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Arth und weis sternen und figuren in früchte zuschneiden,” Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1665). Engraving. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, B641 H25.

*Fruits* Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, a seventeenth-century literary figure, adapted Italian carving manuals for his learned German audience, among many other projects. These images introduce a subsection on the carving of fruit. Shown on top, a dais of solid rectangular blocks anchors a stout column draped with swags of skillfully carved fruits. Atop the column rest carving tools, a book, and two matched pairs of apples and pears. The meaning of this puzzling illustration is revealed by a rhyming verse on the following page: the knife is there to slice the fruit, not the hand nor the truth, since lies should melt into the air without effect and would not therefore need a knife. Several pages of introductory text follow, in which the author gives credit to “Mathematischer Wissenschaften” (mathematical sciences) as the wellspring of knowledge on how to slice and present fruits. Displayed below, a page from this section of the book demonstrates “the way to carve stars and figures of fruits,” inscribing geometric forms onto the abstracted fruit.

Above Top: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Anhang zu dem Andern theil, von früchten schneiden,” em>Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1665). Engraving. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, B641 H25. / Bottom: Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, “Arth und weis sternen und figuren in früchte zuschneiden,” Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch . . . (Nuremberg: Paul Fürst, 1665). Engraving. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, B641 H25.

Mattia Giegher was a Bavarian carver who worked for the German community at the law school of the University of Padua, according to his own preface. Giegher’s carving manual, the first to be profusely illustrated, contains a number of engravings that suggest how to serve fruit as well as meats, fish, and fowl. Here, the skin of the oranges has been skillfully peeled back, leaving flourishes and curlicues of flesh, partially revealing the underlying pith to create a color contrast.

Above: Mattia Giegher, “Melarance,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . , plate 24 (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1639). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Mattia Giegher was a Bavarian carver who worked for the German community at the law school of the University of Padua, according to his own preface. Giegher’s carving manual, the first to be profusely illustrated, contains a number of engravings that suggest how to serve fruit as well as meats, fish, and fowl. Here, the skin of the oranges has been skillfully peeled back, leaving flourishes and curlicues of flesh, partially revealing the underlying pith to create a color contrast.

Left: Mattia Giegher, “Melarance,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . , plate 24 (Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1639). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

L’Art de trancher is undated and contains only engraved images, without text other than the title page. The frontispiece, variations of which appear in other French manuals, displays the hands of the carver demonstrating the Italian method of carving with a small larded bird held on a fork by the left hand and a knife at the ready in the right. His wrists are framed by cuffs of pleated linen trimmed with lace. In the upper-left corner, a pierced sphere with a crown of fleurs-de-lis hints at another skill covered in the books: it is a finished version of one of the geometrically sliced fruits, depicted in both cross section and frontal view in the book, shown below.

L’Art de trancher is undated and contains only engraved images, without text other than the title page. The frontispiece, variations of which appear in other French manuals, displays the hands of the carver demonstrating the Italian method of carving with a small larded bird held on a fork by the left hand and a knife at the ready in the right. His wrists are framed by cuffs of pleated linen trimmed with lace. In the upper-left corner, a pierced sphere with a crown of fleurs-de-lis hints at another skill covered in the books: it is a finished version of one of the geometrically sliced fruits, depicted in both cross section and frontal view in the book, shown below.

Above: Pierre Petit, Frontispiece, from L’Art de trancher . . . (Lyon?, 1647?). Engraving. Special Collections, Regenstein Library, University of Chicago, TX885.P480 1600z c.1.

Fruits, like flesh and fowl, might be sliced in real time in front of the diners. In this late seventeenth-century treatise, “The Modern Steward or the Art of Preparing Banquets Well,” the fruits are labeled with letters that correspond to a legend inserted into a cartouche at the bottom of the page. The fruit labeled “I” depicts “the last cut that one gives for fruit that is carved ‘in aria.’” According to another treatise, the fruit must be sliced quickly without falling from the fork, with the hands barely touching it, making the carver more like a “giocatore di mano” (conjurer) than a carver. With their spiraling peels, these fruits are reminiscent of Dutch still life paintings in which twisting rinds dangle from gleaming platters, symbols of the inexorable passage of time.

Right: Antonio Latini (author) / Francisco De Grado (engraver), Fruits, from Lo Scalco alla Moderna (Naples: Domenico Antonio Parrino and Michele Luigi Mutti, 1694). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Fruits, like flesh and fowl, might be sliced in real time in front of the diners. In this late seventeenth-century treatise, “The Modern Steward or the Art of Preparing Banquets Well,” the fruits are labeled with letters that correspond to a legend inserted into a cartouche at the bottom of the page. The fruit labeled “I” depicts “the last cut that one gives for fruit that is carved ‘in aria.’” According to another treatise, the fruit must be sliced quickly without falling from the fork, with the hands barely touching it, making the carver more like a “giocatore di mano” (conjurer) than a carver. With their spiraling peels, these fruits are reminiscent of Dutch still life paintings in which twisting rinds dangle from gleaming platters, symbols of the inexorable passage of time.

Above: Antonio Latini (author) / Francisco De Grado (engraver), Fruits, from Lo Scalco alla Moderna (Naples: Domenico Antonio Parrino and Michele Luigi Mutti, 1694). Engraving. The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

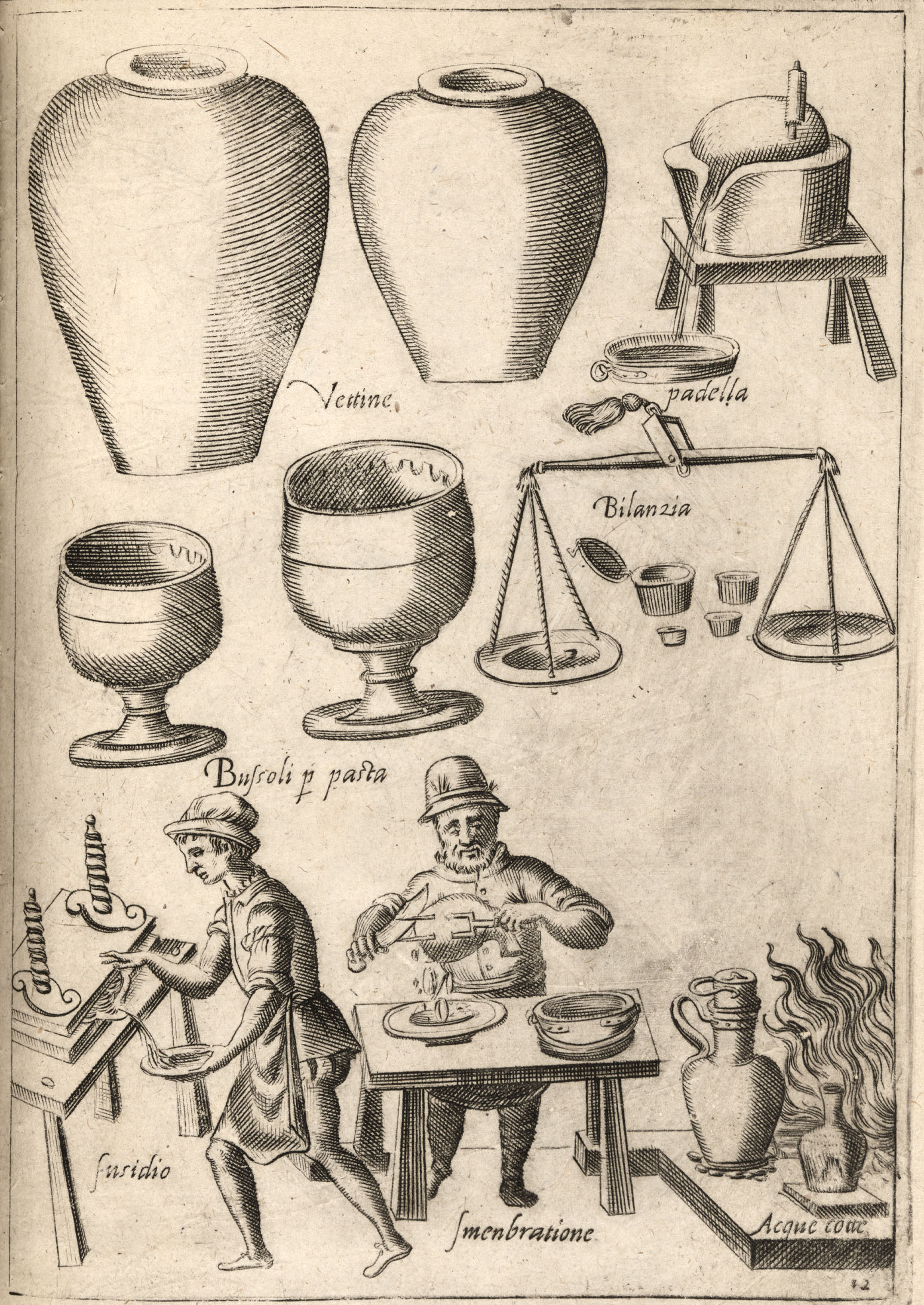

*Carvers in the Kitchen* This engraving from Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera depicts a carver in a kitchen holding a piece of meat with a large, two-tined fork in his left hand, carving it with his right. The caption reads, “smembratione” (dismembering or carving), echoing the caption on one of the knives in Giovanni Francesco Colle’s treatise on view on the landing. Though Scappi’s book does not contain a chapter devoted to carving, this is the earliest representation of carving on the fork. Once the flesh was deposited into the charger waiting below, the remains might have been pressed in the machine to the left in order to release the remaining juices. A reproduction of the same page from a unique hand-colored copy is shown alongside below.

Left: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Vettine,” from Opera . . . , plate 12 (Venice: Michele Tramezzino, 1570). Hand-colored engraving. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Manuscripts and Rare Prints / University Archives 8 OEC I, 3660 RARA. / Right: Bartolomeo Scappi, “Vettine,” from Dell arte de cvcinare, plate 12 (Venice: Combi, 1643). Engraving. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1643 (Scappi, B. M. Bortolomeo [sic] Scappi dell arte del cvcinare) c.2.

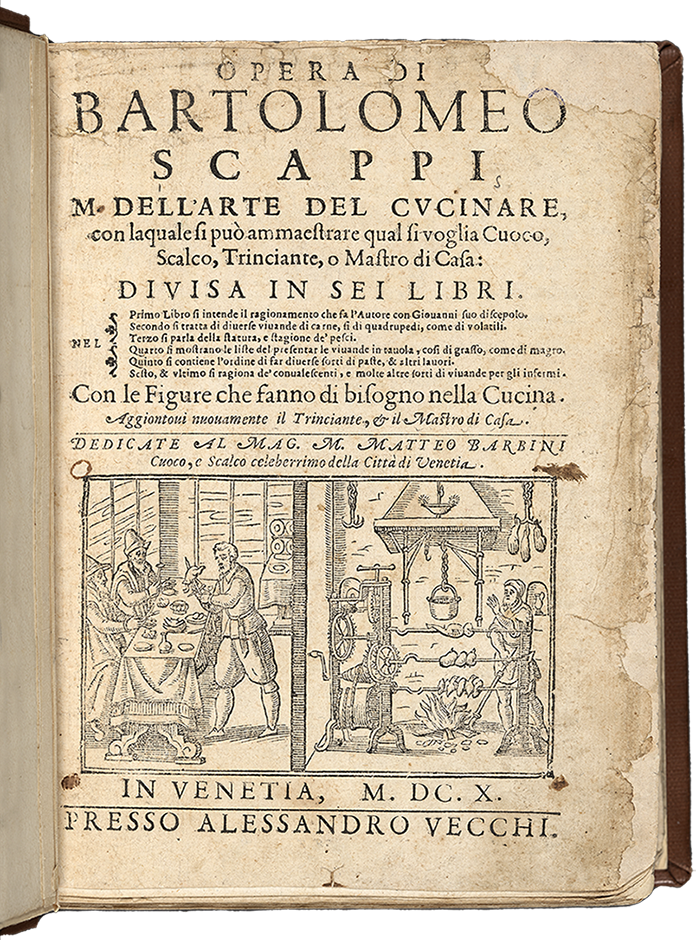

This early seventeenth-century edition of Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera is bound together with Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante. The printer’s device that appeared on earlier editions is replaced with this more marketable title page, giving potential buyers a taste of the book’s contents. The right-hand panel depicts a kitchen with an elaborate clockwork rotisserie on which three spits turn, laden with roasting viands. In the left panel, a carver stands before a table laid for a meal. Demonstrating his skill, he proffers a bird on a fork in aria with his left hand, holding a knife in his right, as instructed in the manuals. The bundling of texts addressing various aspects of food service seems to have been a successful strategy among publishers of manuals or handbooks for both Italian and German markets.

Above / Right: Bartolomeo Scappi, title page with detail, from Opera . . . (Venice: Alessandro Vecchi, 1610). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1610.

This early seventeenth-century edition of Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera is bound together with Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante. The printer’s device that appeared on earlier editions is replaced with this more marketable title page, giving potential buyers a taste of the book’s contents. The right-hand panel depicts a kitchen with an elaborate clockwork rotisserie on which three spits turn, laden with roasting viands. In the left panel, a carver stands before a table laid for a meal. Demonstrating his skill, he proffers a bird on a fork in aria with his left hand, holding a knife in his right, as instructed in the manuals. The bundling of texts addressing various aspects of food service seems to have been a successful strategy among publishers of manuals or handbooks for both Italian and German markets.

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, title page with detail, from Opera . . . (Venice: Alessandro Vecchi, 1610). Woodcut. Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, *KB 1610.