*Tablescapes*

*Tablescapes*

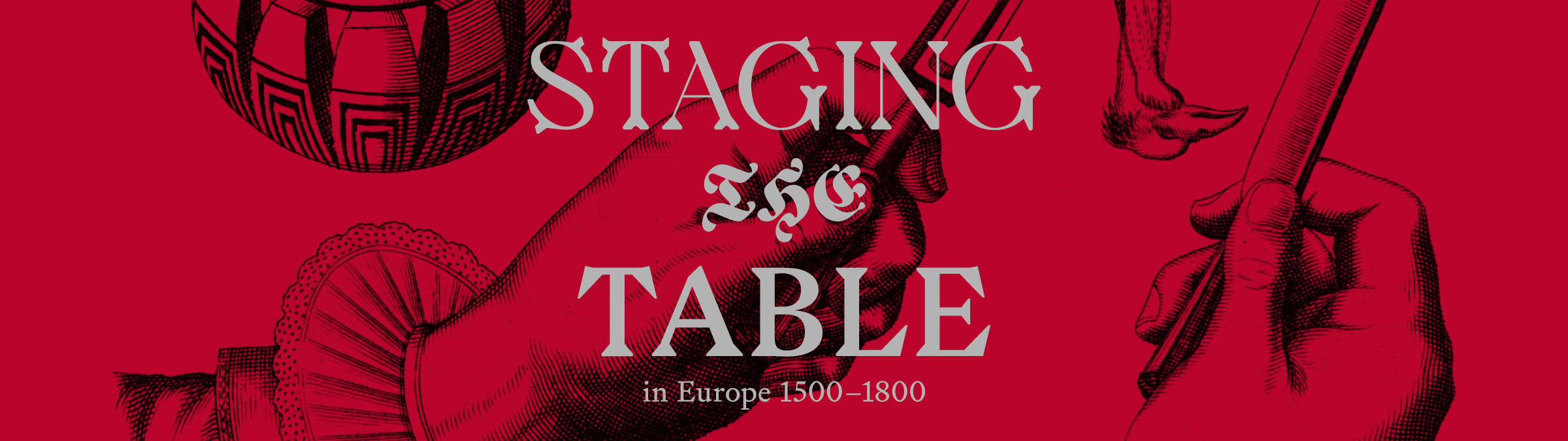

he creation of elaborate, ephemeral sculpture for display on the festive table was, by the early seventeenth century, an entrenched practice at most European courts, both secular and ecclesiastical. In his treatise called Lo Scalco (The Steward), Mattia Giegher instructs that one should place some figures “made of wax, sugar paste, or folded napkins” (cera, o di pasta, o di tovagliuoli), both to ornament the table and mark the importance of the banquet, but also to articulate the spacing of the plates. These sculptural forms were not generally edible even if they were made of foodstuffs like sugar paste, a medium that dried hard and white, resembling porcelain. Although no table sculptures made of ephemeral materials survive, they can be glimpsed through different kinds of documentation, including verbal testimony, receipts, table plans, prints or drawings, paintings, and other visual materials. From a second edition of Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante, the image below shows “how to make a very beautiful apparatus for a women’s table . . . at a wedding, with a very beautiful garden, fishpond, fountains, and statues at very little expense.” For sugar paste sculpture, there are wooden molds dating back to the early modern period that have been used by contemporary historians such as Ivan Day to reconstruct historical tablescapes.

he creation of elaborate, ephemeral sculpture for display on the festive table was, by the early seventeenth century, an entrenched practice at most European courts, both secular and ecclesiastical. In his treatise called Lo Scalco (The Steward), Mattia Giegher instructs that one should place some figures “made of wax, sugar paste, or folded napkins” (cera, o di pasta, o di tovagliuoli), both to ornament the table and mark the importance of the banquet, but also to articulate the spacing of the plates. These sculptural forms were not generally edible even if they were made of foodstuffs like sugar paste, a medium that dried hard and white, resembling porcelain. Although no table sculptures made of ephemeral materials survive, they can be glimpsed through different kinds of documentation, including verbal testimony, receipts, table plans, prints or drawings, paintings, and other visual materials. From a second edition of Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante, the image below shows “how to make a very beautiful apparatus for a women’s table . . . at a wedding, with a very beautiful garden, fishpond, fountains, and statues at very little expense.” For sugar paste sculpture, there are wooden molds dating back to the early modern period that have been used by contemporary historians such as Ivan Day to reconstruct historical tablescapes.

he creation of elaborate, ephemeral sculpture for display on the festive table was, by the early seventeenth century, an entrenched practice at most European courts, both secular and ecclesiastical. In his treatise called Lo Scalco (The Steward), Mattia Giegher instructs that one should place some figures “made of wax, sugar paste, or folded napkins” (cera, o di pasta, o di tovagliuoli), both to ornament the table and mark the importance of the banquet, but also to articulate the spacing of the plates. These sculptural forms were not generally edible even if they were made of foodstuffs like sugar paste, a medium that dried hard and white, resembling porcelain. Although no table sculptures made of ephemeral materials survive, they can be glimpsed through different kinds of documentation, including verbal testimony, receipts, table plans, prints or drawings, paintings, and other visual materials. From a second edition of Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante, the image below shows “how to make a very beautiful apparatus for a women’s table . . . at a wedding, with a very beautiful garden, fishpond, fountains, and statues at very little expense.” For sugar paste sculpture, there are wooden molds dating back to the early modern period that have been used by contemporary historians such as Ivan Day to reconstruct historical tablescapes.

he creation of elaborate, ephemeral sculpture for display on the festive table was, by the early seventeenth century, an entrenched practice at most European courts, both secular and ecclesiastical. In his treatise called Lo Scalco (The Steward), Mattia Giegher instructs that one should place some figures “made of wax, sugar paste, or folded napkins” (cera, o di pasta, o di tovagliuoli), both to ornament the table and mark the importance of the banquet, but also to articulate the spacing of the plates. These sculptural forms were not generally edible even if they were made of foodstuffs like sugar paste, a medium that dried hard and white, resembling porcelain. Although no table sculptures made of ephemeral materials survive, they can be glimpsed through different kinds of documentation, including verbal testimony, receipts, table plans, prints or drawings, paintings, and other visual materials. From a second edition of Vincenzo Cervio’s Il Trinciante, the image below shows “how to make a very beautiful apparatus for a women’s table . . . at a wedding, with a very beautiful garden, fishpond, fountains, and statues at very little expense.” For sugar paste sculpture, there are wooden molds dating back to the early modern period that have been used by contemporary historians such as Ivan Day to reconstruct historical tablescapes.

Above: Vincenzo Cervio, table setting with fishpond, from Il Trinciante . . . (Venice: The Heirs of Giovanni Varisco, 1593). Woodcut. Courtesy the New York Academy of Medicine Library, RB.

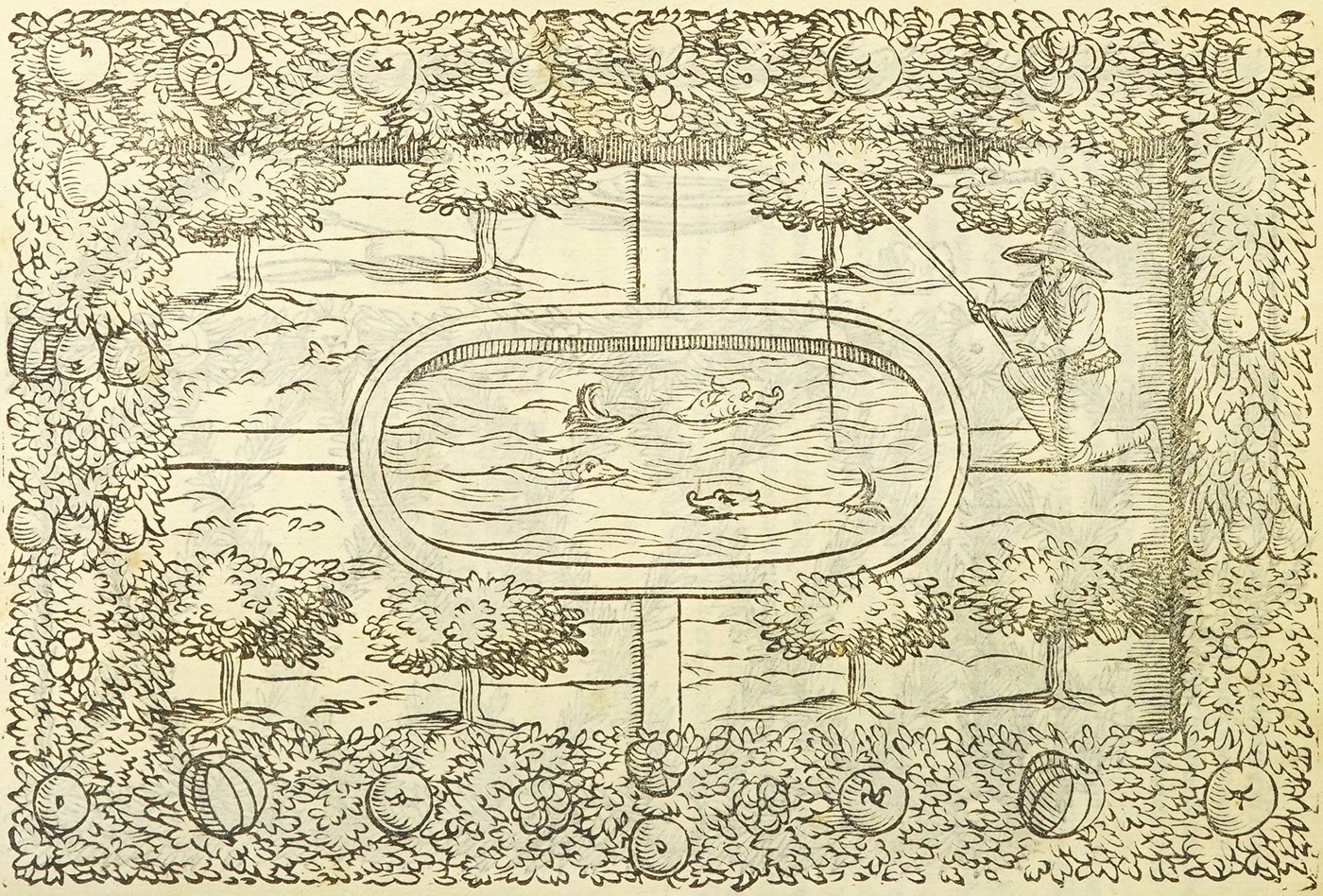

*Festive Events* Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, or at least his publishers, combined material from the Italian carving and folding manuals with more topical description of the celebrations in Nuremberg of the Peace of Westphalia, which marked the end of the Thirty Years War, in 1649. Harsdörffer and his literary and musical collaborators choreographed the events, which included musical, dramatic, military, and gastronomic spectacles. This print depicts a phalanx of servants entering the town hall where the banquet took place, carrying what looks like an entire aviary of exotic birds such as swans and peacocks, stuffed and placed as decorative flourishes on the tops of pies. Musicians located in four raised galleries in the corners of the hall suggest that the banquet was a feast for the ears as well as for the palate.

*Festive Events* Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, or at least his publishers, combined material from the Italian carving and folding manuals with more topical description of the celebrations in Nuremberg of the Peace of Westphalia, which marked the end of the Thirty Years War, in 1649. Harsdörffer and his literary and musical collaborators choreographed the events, which included musical, dramatic, military, and gastronomic spectacles. This print depicts a phalanx of servants entering the town hall where the banquet took place, carrying what looks like an entire aviary of exotic birds such as swans and peacocks, stuffed and placed as decorative flourishes on the tops of pies. Musicians located in four raised galleries in the corners of the hall suggest that the banquet was a feast for the ears as well as for the palate.

From an album depicting various events celebrating the wedding of Alessandro Farnese to Maria of Portugal in Brussels in 1565, this drawing closely follows an account published in Bologna in 1566 that details the multi-day extravaganza. On the right, a cupbearer, dressed in black, hands a goblet to another servant across a barrier enclosing the stepped credenza laden with precious golden plate. A procession of servers enters from offstage like a cavalcade of triumphal soldiers bearing trophies of sugar sculptures in the forms of unicorns and stags, swan and peacock pies, and a boar’s head.

Above: Anonymous, Circle Of Frans Floris, “Banquet at the Brussels Town Hall on 4 December 1565,” from Album Brukselki, ca. 1565. Pen, iron-gall ink, brush, wash, watercolor, gouache, tempera, and deerskin parchment primed with chalk and gum arabic. The Print Room of the University of Warsaw Library, inw.zb.d.10258.

From an album depicting various events celebrating the wedding of Alessandro Farnese to Maria of Portugal in Brussels in 1565, this drawing closely follows an account published in Bologna in 1566 that details the multi-day extravaganza. On the right, a cupbearer, dressed in black, hands a goblet to another servant across a barrier enclosing the stepped credenza laden with precious golden plate. A procession of servers enters from offstage like a cavalcade of triumphal soldiers bearing trophies of sugar sculptures in the forms of unicorns and stags, swan and peacock pies, and a boar’s head.

Left: Anonymous, Circle Of Frans Floris, “Banquet at the Brussels Town Hall on 4 December 1565,” from Album Brukselki, ca. 1565. Pen, iron-gall ink, brush, wash, watercolor, gouache, tempera, and deerskin parchment primed with chalk and gum arabic. The Print Room of the University of Warsaw Library, inw.zb.d.10258.

The theme of the five senses comes from ancient philosophy and was a popular subject in the early modern period. Abraham Bosse’s allegory of taste (Gustus/Le Goût) presents a variety of animal and vegetable symbols: the single artichoke, reputed to be an aphrodisiac, eaten by hand and shared between the couple; the melon, its rounded form suggestive of fertility; and the small lion-trimmed dog in the foreground, avidly enjoying its repast. Inscriptions in Latin and French, likely written by Bosse himself, celebrate taste as “the king of the senses,” but also recommend resistance to excess in favor of moderation. The crisply starched, folded, andpressed tablecloth signals the labor needed to produce it, a marker of status and refinement.

The theme of the five senses comes from ancient philosophy and was a popular subject in the early modern period. Abraham Bosse’s allegory of taste (Gustus/Le Goût) presents a variety of animal and vegetable symbols: the single artichoke, reputed to be an aphrodisiac, eaten by hand and shared between the couple; the melon, its rounded form suggestive of fertility; and the small lion-trimmed dog in the foreground, avidly enjoying its repast. Inscriptions in Latin and French, likely written by Bosse himself, celebrate taste as “the king of the senses,” but also recommend resistance to excess in favor of moderation. The crisply starched, folded, andpressed tablecloth signals the labor needed to produce it, a marker of status and refinement.

Right: Abraham Bosse, Taste (The Five Senses), published by Melchior Tavernier, 1635–38. Etching. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926, 26.49.25.

This print was very likely the source for the Georg Philipp Harsdörffer title page displayed below. A woman sits at the head of a table with friends, next to a blazing hearth. The verse below expresses the women’s pleasure at indulging themselves in food and drink, behavior that was evidently not possible with their husbands around. The windows are thrown open to reveal an elaborate garden as they indulge in wine and feast on turkey, sausage, and other delicacies. Pets and children romp playfully, giving this print a subversive quality that Harsdörffer’s adaptation lacks. It is impossible to know whether any German readers of Harsdörffer’s books were aware of the Bosse quotation, but it is a useful reminder of the mobility of print culture.

Above: Abraham Bosse, Wives at the Table during the Absence of their Husbands, published by Jean I Leblond, ca. 1636. Etching. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926, 26.49.63.

This print was very likely the source for the Georg Philipp Harsdörffer title page displayed below. A woman sits at the head of a table with friends, next to a blazing hearth. The verse below expresses the women’s pleasure at indulging themselves in food and drink, behavior that was evidently not possible with their husbands around. The windows are thrown open to reveal an elaborate garden as they indulge in wine and feast on turkey, sausage, and other delicacies. Pets and children romp playfully, giving this print a subversive quality that Harsdörffer’s adaptation lacks. It is impossible to know whether any German readers of Harsdörffer’s books were aware of the Bosse quotation, but it is a useful reminder of the mobility of print culture.

A dozen well-dressed people are in the midst of a festive meal. A woman occupies the head of the table, wearing a large lace collar and an elaborate coiffure. In her right hand, she holds a two-tined fork. To her right stands a carver holding more carving tools, a cloth draped over his left arm. He looks expectantly at the woman holding the fork, as if he is politely requesting that she return the fork so that he can proceed with the task at hand. Just behind him stands a page, who holds a stack of plates awaiting their charge. The table is set with a linen tablecloth that bears crisp folds, signaling the back-of-house attention to the care of fine linens—a mark of status. The image bears a remarkable similarity to Abraham Bosse’s print, clearly its inspiration, shown above. The crucifixion over the mantel in the Bosse print is replaced here by a more generic scene, not surprising for a Protestant audience, and the pets and children appropriate to a gathering of women have been banished.

A dozen well-dressed people are in the midst of a festive meal. A woman occupies the head of the table, wearing a large lace collar and an elaborate coiffure. In her right hand, she holds a two-tined fork. To her right stands a carver holding more carving tools, a cloth draped over his left arm. He looks expectantly at the woman holding the fork, as if he is politely requesting that she return the fork so that he can proceed with the task at hand. Just behind him stands a page, who holds a stack of plates awaiting their charge. The table is set with a linen tablecloth that bears crisp folds, signaling the back-of-house attention to the care of fine linens—a mark of status. The image bears a remarkable similarity to Abraham Bosse’s print, clearly its inspiration, shown above. The crucifixion over the mantel in the Bosse print is replaced here by a more generic scene, not surprising for a Protestant audience, and the pets and children appropriate to a gathering of women have been banished.

Diners are seated at a table in the garden of an Italianate villa before a credenza laden with gold and silver vessels. The stepped structure is framed by an arbor festooned with flowers and greenery, atop which musicians play. A steward or carver stands in front of the table with his back to the viewer, a white cloth draped over his shoulder. He is pulling back the tablecloth to reveal the board beneath, perhaps signaling that this is the final course. To the right, large flasks stand cooling in a basin very similar to that in the frontispiece from Andreas Klett’s book, shown below. Musicians serenade the feast, while a servant at the fishpond supervises the catch.

Diners are seated at a table in the garden of an Italianate villa before a credenza laden with gold and silver vessels. The stepped structure is framed by an arbor festooned with flowers and greenery, atop which musicians play. A steward or carver stands in front of the table with his back to the viewer, a white cloth draped over his shoulder. He is pulling back the tablecloth to reveal the board beneath, perhaps signaling that this is the final course. To the right, large flasks stand cooling in a basin very similar to that in the frontispiece from Andreas Klett’s book, shown below. Musicians serenade the feast, while a servant at the fishpond supervises the catch.

Above: Hans Mielich, Outdoor Banquet, 1548. Oil on panel. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Caitlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1949.199.

An edition published in 1724 reflects contemporary trends in architecture and landscape design. A party of six is seated around a table in front of a classicizing pavilion in a formal garden with a damask-patterned parterre. The trinciante stands at one end of the table, holding a fowl on a fork. To the right, a drinks cooler sits on an elaborate table.

Right: Andreas Klett, frontispiece, from Wohl-informirter Tafel-Decker und Trenchant . . . (Nuremberg: Buggel und Seitz, 1724). Engraving. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 50 MA 10701.

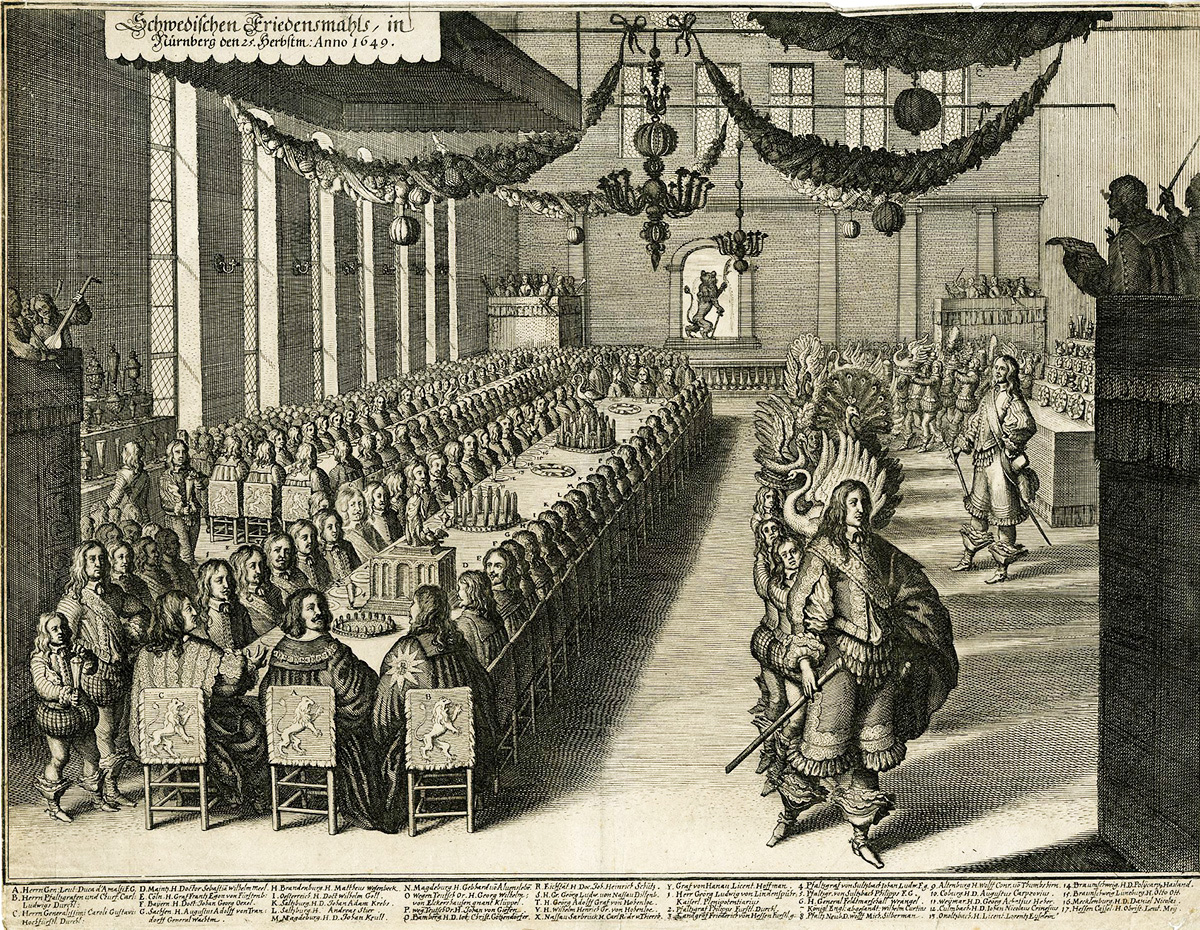

*Mapping the Table* Table maps such as this appear for the first time in Mattia Giegher’s Lo Scalco. This one depicts a specific dish. An oglia putrida, literally “rotten pot,” was a fashionable Spanish stew made with a variety of meats, fowl, and vegetables cooked together and placed in the middle of the table on a large plate, a kind of extravaganza that apparently required its own choreography. The various kinds of meats are indicated in a numbered list that is keyed to an octagonal table: fegato (liver), salsiccione (sausage), prosciutto, carne lessa (boiled meat), and trippe (tripe).

*Mapping the Table* Table maps such as this appear for the first time in Mattia Giegher’s Lo Scalco. This one depicts a specific dish. An oglia putrida, literally “rotten pot,” was a fashionable Spanish stew made with a variety of meats, fowl, and vegetables cooked together and placed in the middle of the table on a large plate, a kind of extravaganza that apparently required its own choreography. The various kinds of meats are indicated in a numbered list that is keyed to an octagonal table: fegato (liver), salsiccione (sausage), prosciutto, carne lessa (boiled meat), and trippe (tripe).

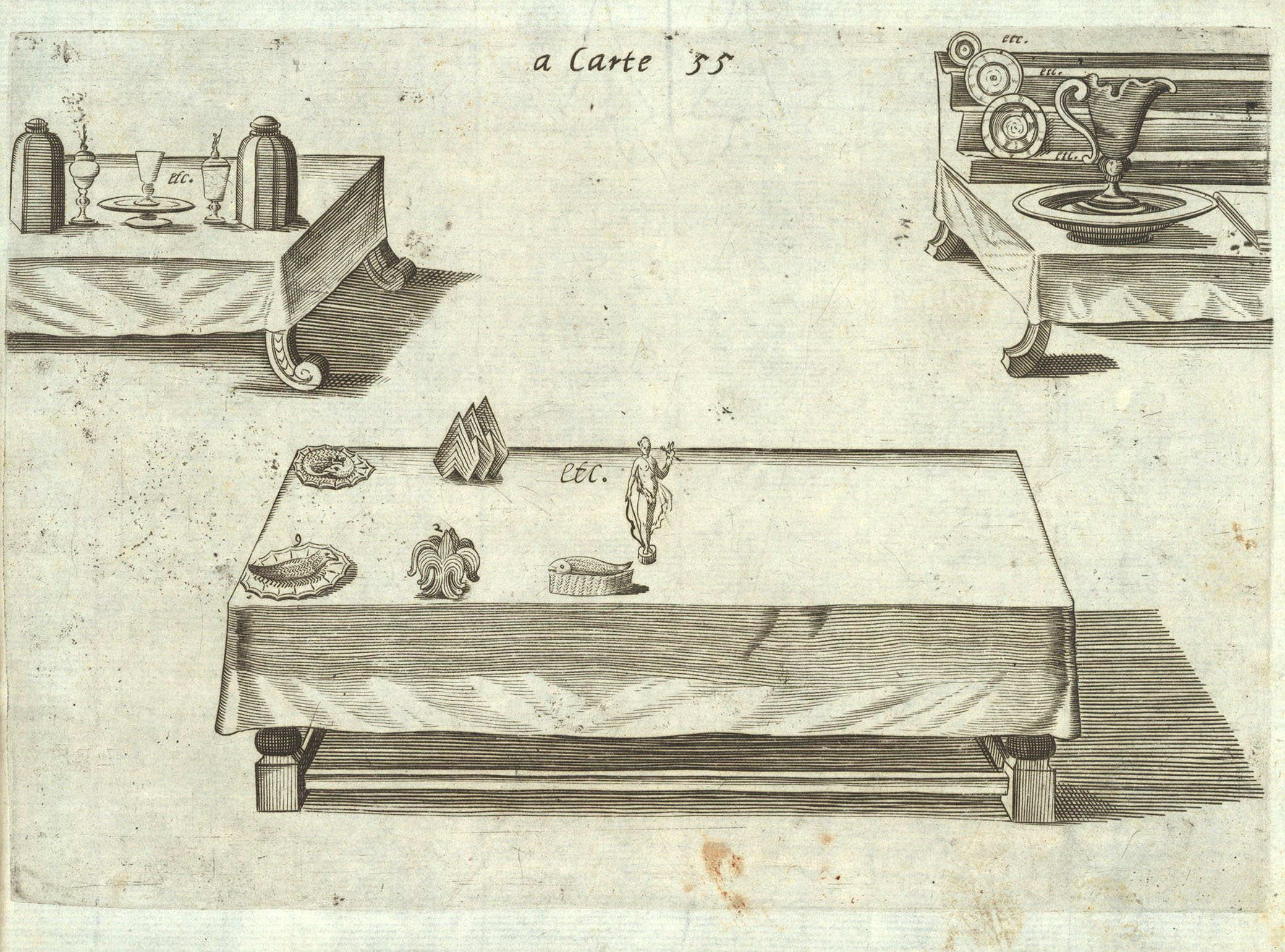

Under the heading “A reminder of how to decorate the table with various figures,” Giegher lists forms that might be made of sugar paste or wax: pyramids, castles, eagles, lions, stags, dragons, a Satyr, a Mars, a Hercules, a Europa on the bull with her hands on its horns, a clothed Trojan Helen with golden hair, and various nudes: Venus, Pallas, and Juno. Folded napkins and sculptural forms are represented on the central table. The credenza, to the right, features a ewer and basin, and plates.

Above: Mattia Giegher, “A carte 55,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

Under the heading “A reminder of how to decorate the table with various figures,” Giegher lists forms that might be made of sugar paste or wax: pyramids, castles, eagles, lions, stags, dragons, a Satyr, a Mars, a Hercules, a Europa on the bull with her hands on its horns, a clothed Trojan Helen with golden hair, and various nudes: Venus, Pallas, and Juno. Folded napkins and sculptural forms are represented on the central table. The credenza, to the right, features a ewer and basin, and plates.

Left: Mattia Giegher, “A carte 55,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

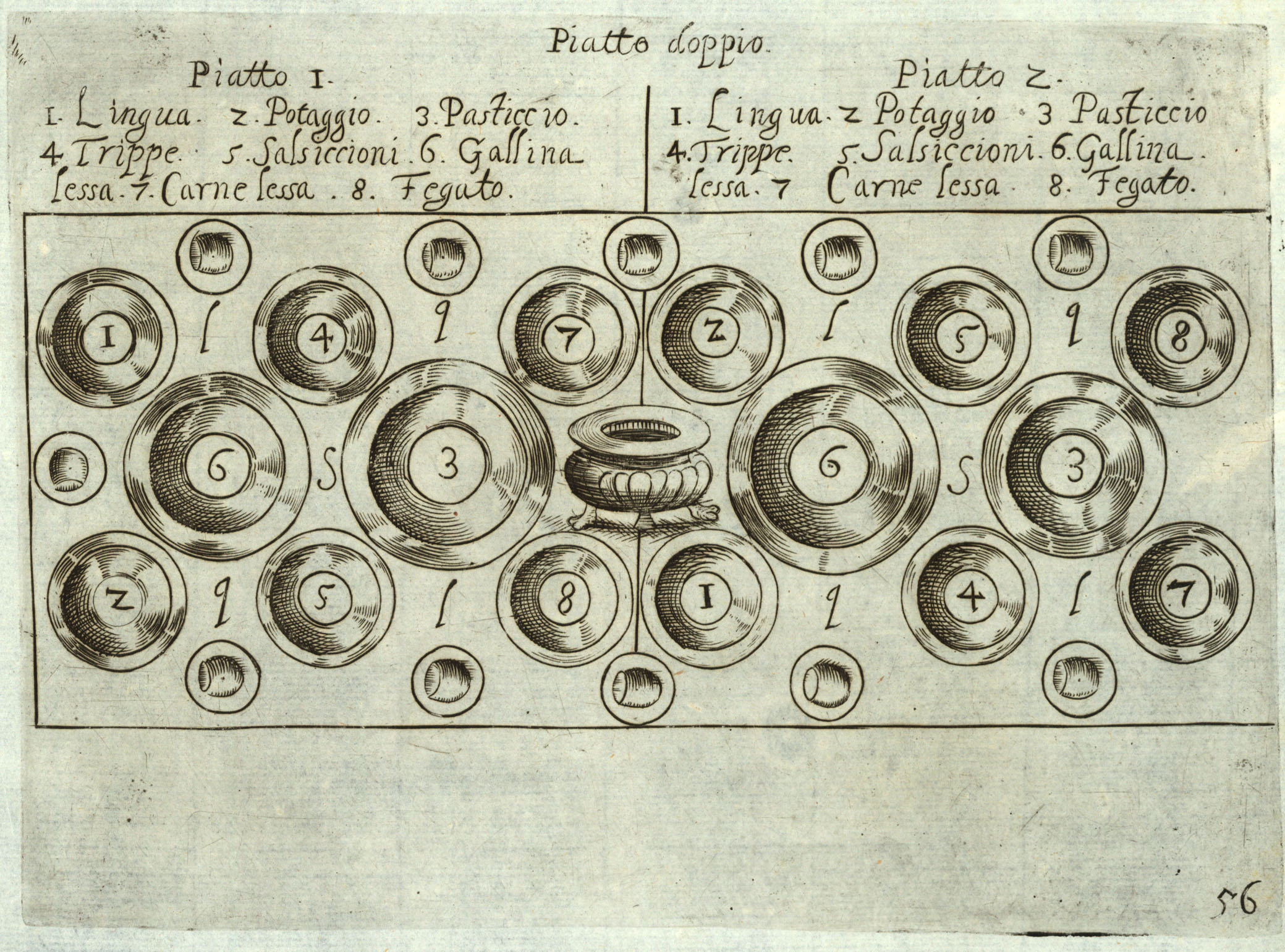

As this table plan indicates, each course of a meal, or “piatto,” consisted of several dishes set out at the same time. The combination and choice of placement fell to the steward. Diners would probably partake of the dishes closest to them, though they may also have asked to taste dishes that were out of reach. One piatto would serve four to six people, so the size of the table would be adjusted according to the number of diners. For eight people, a piatto doppio was required, etc. Proper placement of the saltcellars is indicated by the letter S for saliera in two locations on the table, while the Q and L stand for qua and la, here and there, for other dishes based on personal choice.

As this table plan indicates, each course of a meal, or “piatto,” consisted of several dishes set out at the same time. The combination and choice of placement fell to the steward. Diners would probably partake of the dishes closest to them, though they may also have asked to taste dishes that were out of reach. One piatto would serve four to six people, so the size of the table would be adjusted according to the number of diners. For eight people, a piatto doppio was required, etc. Proper placement of the saltcellars is indicated by the letter S for saliera in two locations on the table, while the Q and L stand for qua and la, here and there, for other dishes based on personal choice.

Right: Mattia Giegher, “Piatto doppio,” from Li Tre Trattati . . . (Padua: Guaresco Guareschi al Pozzo dipinto, 1629). Engraving. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, AP V 31a.

*Table Service* One of the earliest illustrated recipe books in Europe, Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera features twenty-seven engravings that depict kitchens, cooking implements such as pots and pans, and other objects associated with preparing and serving food. This double-page illustration of food service for the papal conclave of 1549 provides unique visual documentation of how food moved from the kitchen to the table in a large household.

Elaborate efforts were enacted to prevent contact between the cardinals, who were sequestered while they elected the next pope, and the outside world. Baskets with drawstring covers emblazoned with coats-of-arms, locked hampers, and bottle carriers are transported by a battalion of servants. Other items with locks reinforce the aura of secrecy and security that pervaded the conclave, with assayers poised to examine each and every morsel of food and drink before it passed through the revolving compartments to the hungry cardinals. In the detailed description that accompanies the image, Scappi, one of the personal chefs of the pope, reports that closed pies or whole chickens were not allowed because they would be inspected—and presumably ruined—by the tasters. One of the longest on record, the conclave lasted for seventy-two days and was, according to one papal historian, “unusual for the blatant disregard of the rules.”

Elaborate efforts were enacted to prevent contact between the cardinals, who were sequestered while they elected the next pope, and the outside world. Baskets with drawstring covers emblazoned with coats-of-arms, locked hampers, and bottle carriers are transported by a battalion of servants. Other items with locks reinforce the aura of secrecy and security that pervaded the conclave, with assayers poised to examine each and every morsel of food and drink before it passed through the revolving compartments to the hungry cardinals. In the detailed description that accompanies the image, Scappi, one of the personal chefs of the pope, reports that closed pies or whole chickens were not allowed because they would be inspected—and presumably ruined—by the tasters. One of the longest on record, the conclave lasted for seventy-two days and was, according to one papal historian, “unusual for the blatant disregard of the rules.”

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, Order and procedures for serving cardinals food and beverages, from Opera . . . (Venice or Rome: Michele Tramezzino, 1570). Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1952, 52.595.2.

Above: Bartolomeo Scappi, Order and procedures for serving cardinals food and beverages, from Opera . . . (Venice or Rome: Michele Tramezzino, 1570). Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1952, 52.595.2.

*Tabletop Menagerie* Vessels that embodied the food they might serve brought humor and playfulness to the table and are found in a variety of materials, including silver, porcelain, and earthenware. A standard offering at celebratory feasts from antiquity to the present, wild boar was valued for the difficulty of its capture—it is a powerful animal with large, sharp teeth—and the tastiness of its flesh. Recipes for wild boar appear in most early modern cookbooks in many different preparations. Instructions for carving up boar’s heads are standard fare in the carving manuals.

Right: Delft boar’s head tureen and stand, ca. 1750–60. Faience. Courtesy Michele Beiny Harkins.

Turkeys arrived in Seville in the early sixteenth century under the auspices of King Ferdinand of Spain and were immediately celebrated for their tasty meat. They appear in Italian, German, French, and English recipe books and menus from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as in many depictions of festive meals. The upper section of the bird may be lifted to reveal a capacious basin. Trompe l’oeil tureens such as the boar and turkey were likely used to serve stews or soups with ingredients signaled by their form.

Above: Turkey tureen, Brussels (Rue de Laeken Factory), Philippe Mombaers period, ca. 1760. Faience. Courtesy Michele Beiny Harkins.

Turkeys arrived in Seville in the early sixteenth century under the auspices of King Ferdinand of Spain and were immediately celebrated for their tasty meat. They appear in Italian, German, French, and English recipe books and menus from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as in many depictions of festive meals. The upper section of the bird may be lifted to reveal a capacious basin. Trompe l’oeil tureens such as the boar and turkey were likely used to serve stews or soups with ingredients signaled by their form.

Left: Turkey tureen, Brussels (Rue de Laeken Factory), Philippe Mombaers period, ca. 1760. Faience. Courtesy Michele Beiny Harkins.

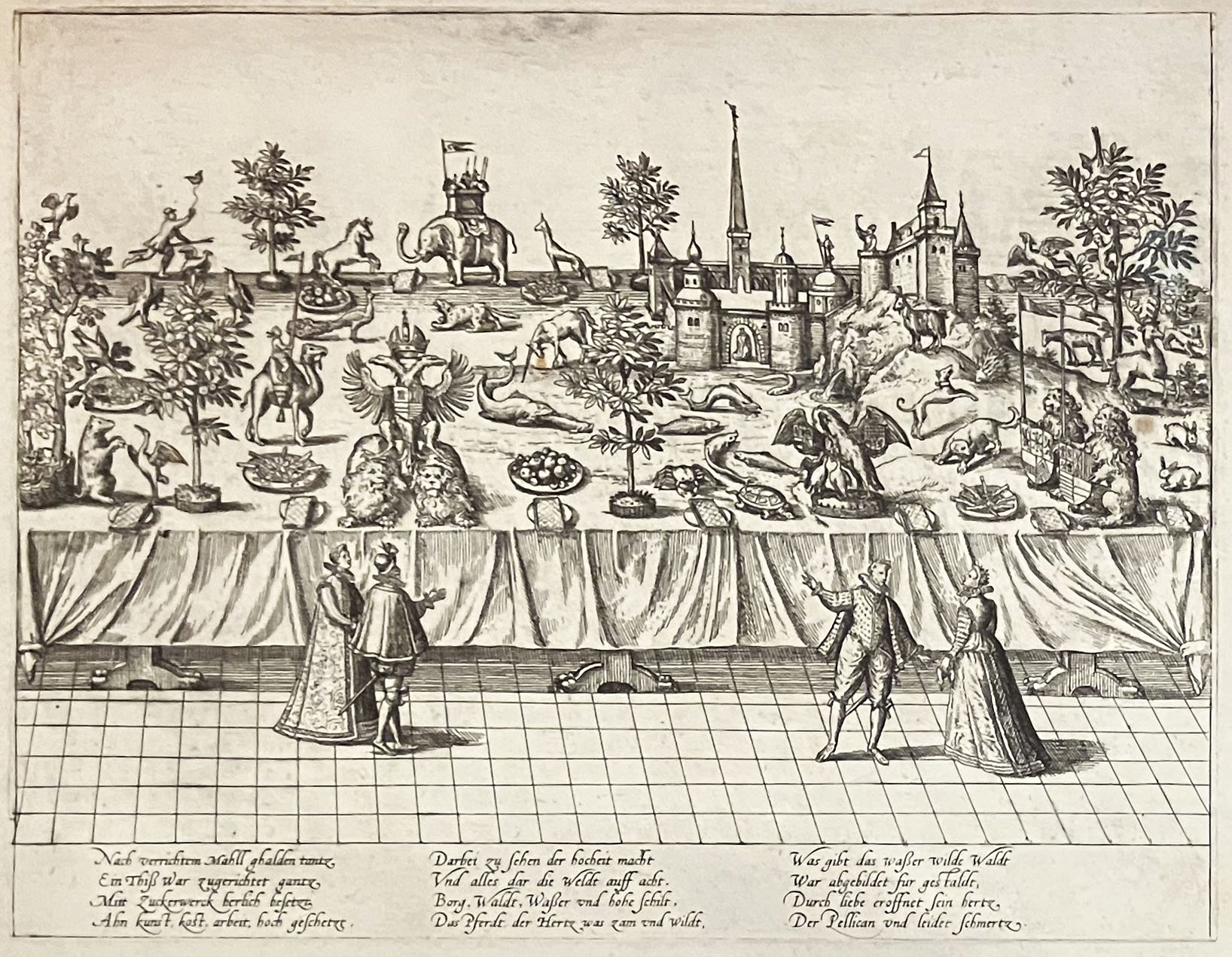

This rare proof of a print, published in an illustrated book commemorating the marriage of Johann Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, and Jacoba, Margravine of Baden, which took place in Düsseldorf on June 16, 1585, depicts a table laden with a menagerie of sugar sculpture. Wedding guests, dwarfed by the fantastic beasts and elaborate structures that fill the surface of the enormous draped table, can almost be heard exclaiming at the wondrous display. The front row includes a double-headed eagle, supported by two recumbent lions, and the Pelican of Piety. Potted plants, horses, fish, rabbits, turtles, a bear, a peacock, and even an elephant populate the table. Verses below explain that the display was prepared of sugarwork with skill, expense, labor, and care.

This rare proof of a print, published in an illustrated book commemorating the marriage of Johann Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, and Jacoba, Margravine of Baden, which took place in Düsseldorf on June 16, 1585, depicts a table laden with a menagerie of sugar sculpture. Wedding guests, dwarfed by the fantastic beasts and elaborate structures that fill the surface of the enormous draped table, can almost be heard exclaiming at the wondrous display. The front row includes a double-headed eagle, supported by two recumbent lions, and the Pelican of Piety. Potted plants, horses, fish, rabbits, turtles, a bear, a peacock, and even an elephant populate the table. Verses below explain that the display was prepared of sugarwork with skill, expense, labor, and care.

Above: Attributed To Frans Hogenberg, table setting of sugar paste sculptures of animals, birds, fish and trees for the wedding of Johann Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg and Jacoba, Margravine of Baden, published, presumably later, in Diederich Graminaeus, Beschreibung derer Fürstlicher Güligscher ec. Hochzeit (Cologne 1587) Etching. Collection of Thomas Heneage.

Above: Attributed To Frans Hogenberg, table setting of sugar paste sculptures of animals, birds, fish and trees for the wedding of Johann Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg and Jacoba, Margravine of Baden, published, presumably later, in Diederich Graminaeus, Beschreibung derer Fürstlicher Güligscher ec. Hochzeit (Cologne 1587) Etching. Collection of Thomas Heneage.

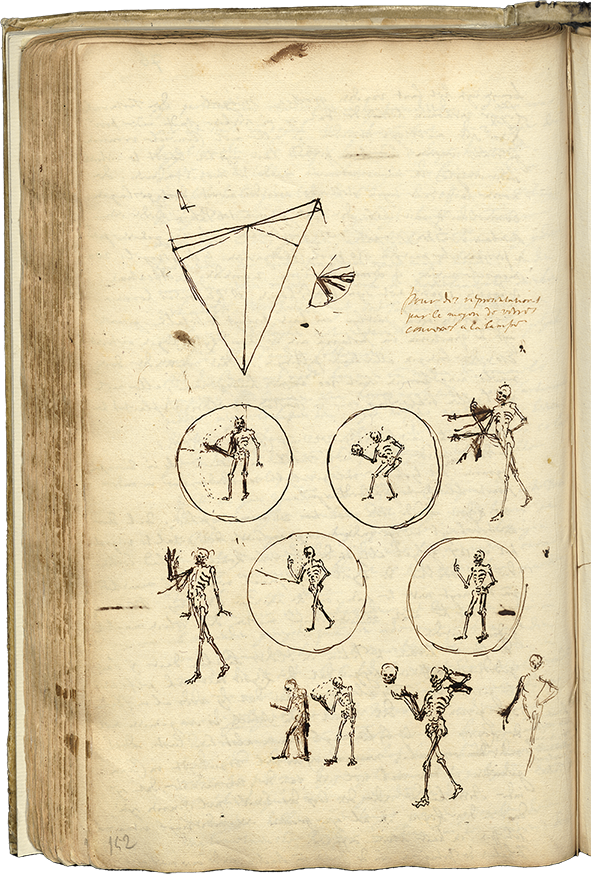

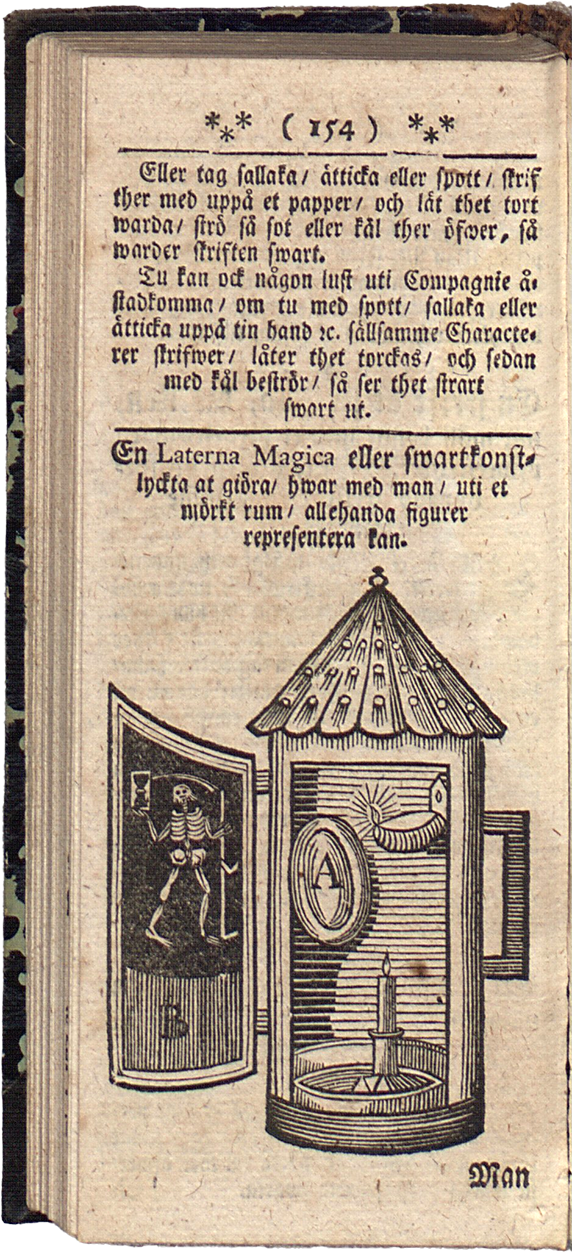

*Table Magic* The caption on this sketch from the notebooks of Christiaan Huygens, a noted Dutch mathematician, physicist, and astronomer, reads: “For representations by means of convex glasses before a lamp.” The magic lantern, clearly referenced here, is ultimately considered the ancestor of film and is just one of many inventions ascribed to Huygens. The figures are drawn in a variety of poses, some with an arc implying range of movement, as might be achieved through projection. The depiction of the skeleton in some of the later carving and folding books is similar to Huygens’s sketches.

*Table Magic* The caption on this sketch from the notebooks of Christiaan Huygens, a noted Dutch mathematician, physicist, and astronomer, reads: “For representations by means of convex glasses before a lamp.” The magic lantern, clearly referenced here, is ultimately considered the ancestor of film and is just one of many inventions ascribed to Huygens. The figures are drawn in a variety of poses, some with an arc implying range of movement, as might be achieved through projection. The depiction of the skeleton in some of the later carving and folding books is similar to Huygens’s sketches.

Right: Christiaan Huygens, “Pour des représentations par le moyen de verres convexes à la lampe,” 1658–60. Ink on paper. Leiden University Library, Special collections (HUG 10) MS. HUG 10, folio 76v.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, carving manuals were being brought out all over Northern Europe, such as this one from Sweden. Along with carving, this book contains poems to be recited at the table, recipes for invisible inks, and a chapter with ninety-seven magic tricks: how to make a candle that lights itself; how to make a playing card move around the table using a hair attached with wax; and how to make a roast chicken jump off a dish and run around when someone begins to carve it, among others. Several related books feature a magic lantern accompanied by the caption “a magic lantern, or black art.” The device functioned by means of a concave mirror behind a candle that would direct the light through a small sheet of glass with the image painted on it. The resulting projection would be magically enlarged and the flickering candle would make it appear to be moving, inspiring wonder and awe in the diners.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, carving manuals were being brought out all over Northern Europe, such as this one from Sweden. Along with carving, this book contains poems to be recited at the table, recipes for invisible inks, and a chapter with ninety-seven magic tricks: how to make a candle that lights itself; how to make a playing card move around the table using a hair attached with wax; and how to make a roast chicken jump off a dish and run around when someone begins to carve it, among others. Several related books feature a magic lantern accompanied by the caption “a magic lantern, or black art.” The device functioned by means of a concave mirror behind a candle that would direct the light through a small sheet of glass with the image painted on it. The resulting projection would be magically enlarged and the flickering candle would make it appear to be moving, inspiring wonder and awe in the diners.

Left: Magic lantern, from En mycket nyttig och förbättrad trenchier-bok . . . , page 154 (Västerås: Johann Laurens Horrn, 1766). Engraving. Conjuring Arts Research Center, New York.