Lace and the Seventeenth-Century French Economy

In 1665 Louis XIV (1638–1715) and his ambitious finance minister Jean- Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) established the French lace industry. Determined to curtail the enormous expenditures by French elites on Flemish and Italian laces that had dominated the European market since the early seventeenth century, Colbert founded manufactories in existing lacemaking centers such as Alençon and Sedan. There, lacemakers produced high-quality needle and bobbin laces known as points de France, which would soon rival foreign products. In addition to luring mistresses and their workers from the Southern Netherlands and the Italian peninsula to teach their techniques to French lacemakers, Colbert commissioned designs from leading artists like Jean Bérain (1640–1711).

Left:

Claude Lefèbvre, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1666. Oil on canvas. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, MV 2185. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Christophe Fouin.

Right:

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XIV (1638–1715), King of France, 1701. Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris, INV7492. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Stéphane Maréchalle.

Top:

Claude Lefèbvre, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1666. Oil on canvas. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, MV 2185. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Christophe Fouin.

Bottom:

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XIV (1638–1715), King of France, 1701. Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris, INV7492. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Stéphane Maréchalle.

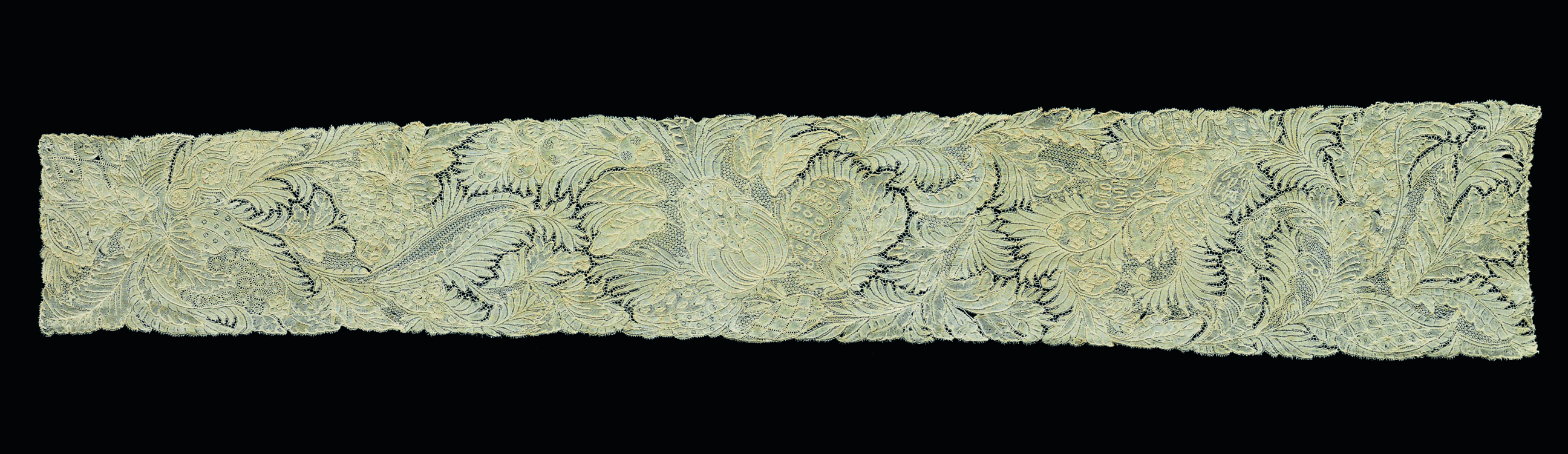

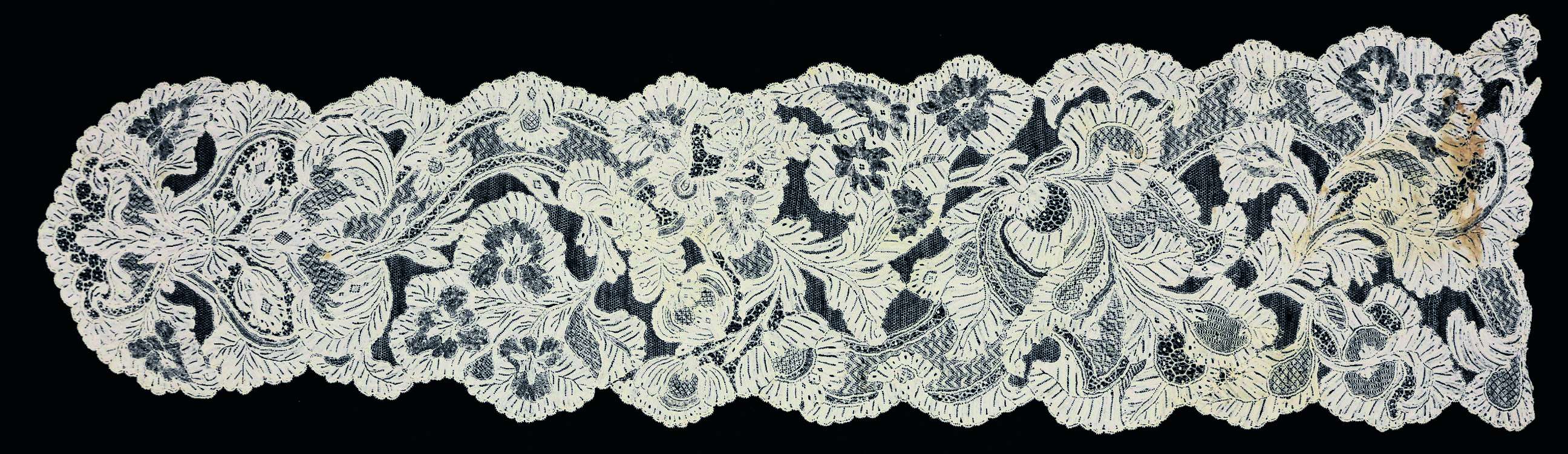

Initially, French laces imitated the much more robust and three-dimensional points qui se font à Venise (laces made in Venice) with large scrolling florals and foliage. By the end of the century, however, point de France had transformed into a light needle lace with small-scale symmetrical designs that superseded its earlier Venetian competitor as the most fashionable type of lace in France and throughout Europe.

Fashions in Lace Accessories

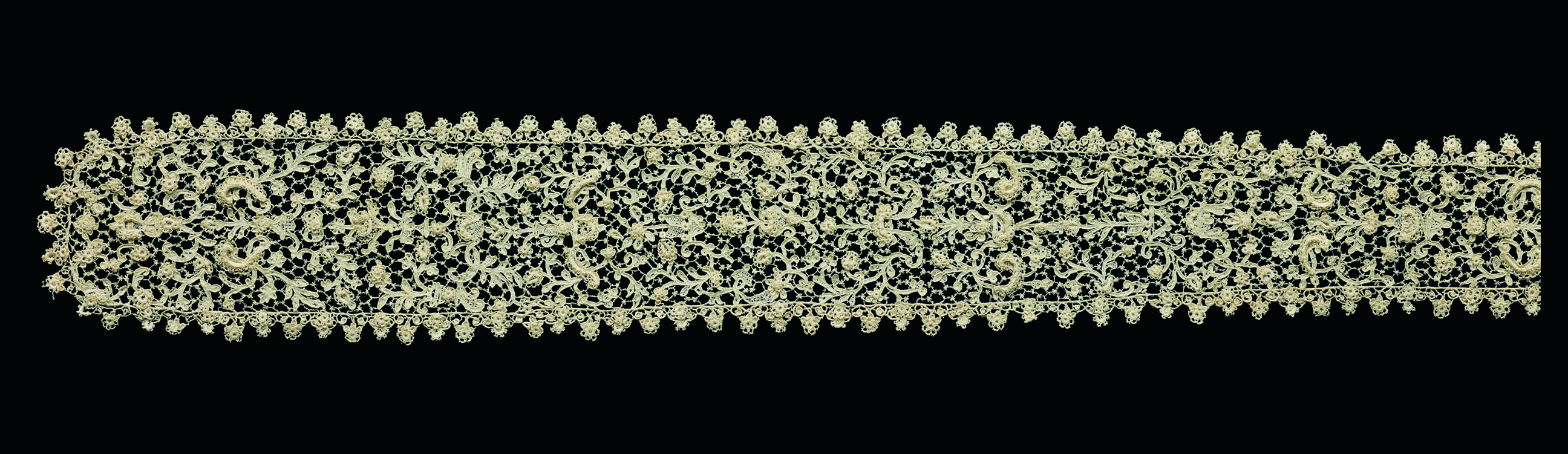

Throughout the eighteenth century, lace accessories including caps, lappets, sleeve ruffles, cravat ends, and jabots provided an elegant finishing touch to women’s gowns and men’s suits and displayed the wearer’s taste and purchasing power. The cost of a piece of lace was determined by the length of time it took to make, which, in turn, depended on its size, the quality of the thread, and the complexity of the design. A lacemaker in France, who earned between two and thirteen sols (pennies) a day, could spend up to a year producing a set of sleeve ruffles of the finest point d’Alençon, point d’Argentan, or Valenciennes to be sold by a merchant at a significant markup.

Click Image to View Slideshow

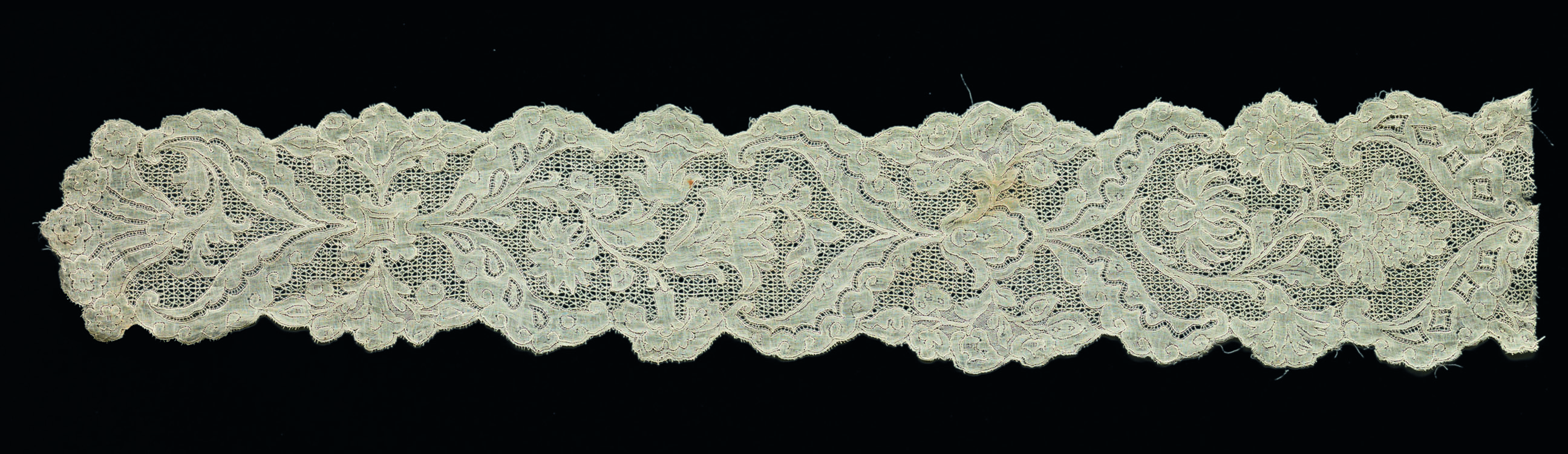

ca. 1700

Linen

Textilmuseum St. Gallen,

Acquired from the Estate of John Jacoby, 1954, 01203

Photo: Michael Rast

ca. 1695

Linen

Textilmuseum St. Gallen, Acquired from the Estate of John Jacoby, 1954, 01246

Photo: Michael Rast

Although fashions in lace changed over the course of the century, this luxury textile was often passed down from one generation to another and could be restyled into more up-to-date forms. Its economic worth is reflected by its inclusion in contemporary probate inventories that listed the possessions of deceased individuals. At the time of her death in 1764, the lace accessories owned by Madame de Pompadour (b. 1721), official mistress to Louis XV (1715–1774), constituted nearly half of the substantial value of her wardrobe and likely represented many years of accumulation.

ca. 1755–60

Chinese export brocaded silk satin, trimmed with silk chenille looped fringe

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the John D. McIlhenny Fund, the John T. Morris Fund, the Elizabeth Wandell Smith Fund, and with funds contributed by Mrs. Howard H. Lewis and Marion Boulton Stroud, 1988, 1988-83-1a–c

The Lives of Lacemakers

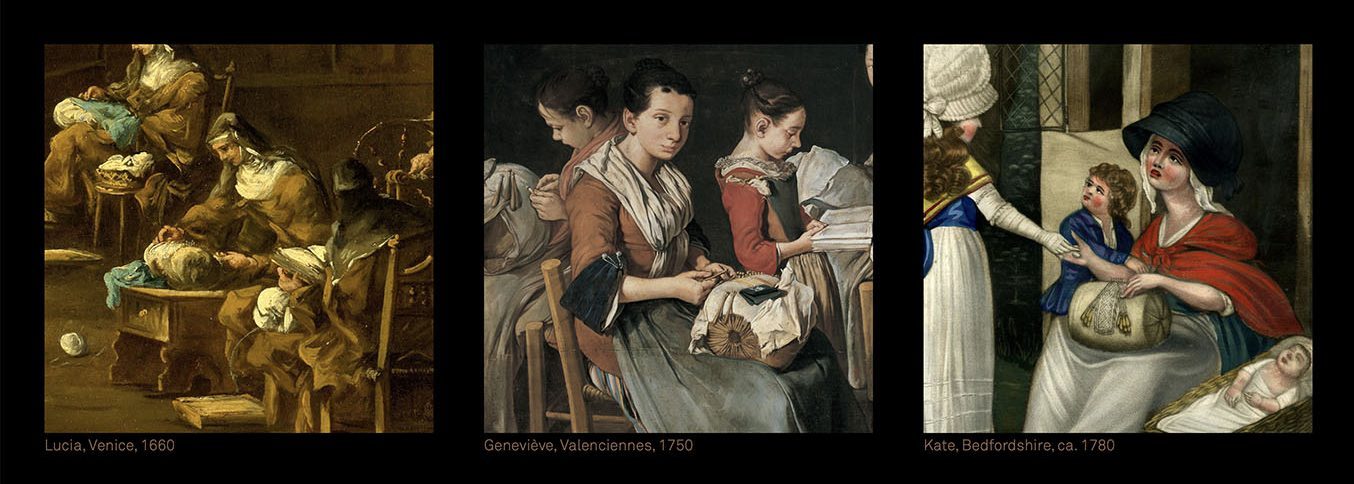

Students at Bard Graduate Center developed this interactive on display in the exhibition to offer a window into the lives of women and girls who created lace during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and whose names are no longer known to us. Informed by the surviving records related to lacemaking during this period, this exploration imagines the circumstances of three fictional young lacemakers: Lucia, who lives in Venice in 1660; Geneviève, who lives in Valenciennes, France, in 1750; and Kate, who lives in Bedfordshire, England, around 1780.

Click through to learn details about their families, lace education, local industries, tools and materials, daily lives, and cultures and communities.

Developed by Grace Billingslea, Caroline Elenowitz-Hess, and Isabella Margi.