The Emergence of Lace in Early Modern Europe

Lace refers to many forms of nonwoven textiles with designs characterized by open spaces. European needle and bobbin laces developed in the mid- to late sixteenth century from existing decorative techniques: embroidery and braiding, respectively. Using these two basic tools, needles and bobbins, to manipulate thread, female lacemakers created a wide range of trimmings and accessories from simple narrow edgings to wide, densely patterned collars.

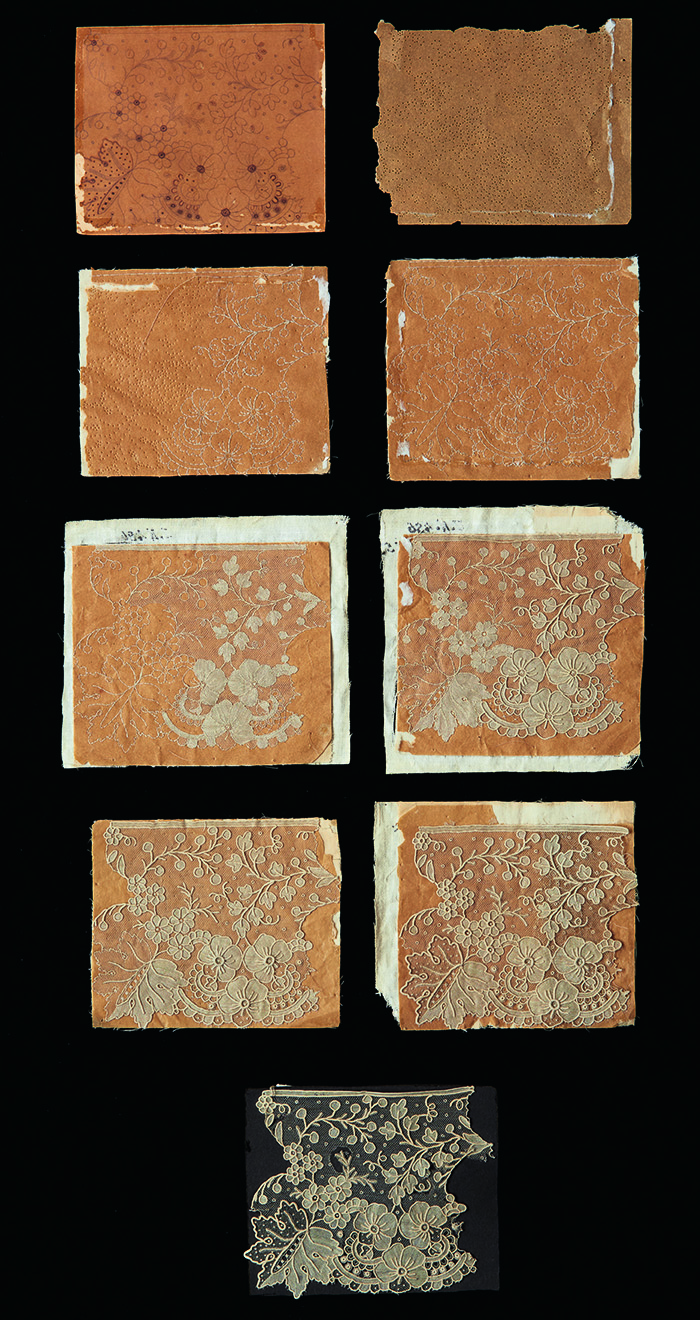

Both needle and bobbin lacemakers began with a design drawn in ink on parchment that served as a guide. The needle lacemaker traced the design’s outlines with loosely worked stitches that pierced the parchment base to form a scaffold for the lace. She deftly built up the main motifs over these threads, gradually filling in the connecting mesh and additional details primarily using buttonhole stitches. Once she had completed the piece, the lacemaker cut the outlining threads from the back of the parchment, releasing the finished lace.

The bobbin lacemaker began by attaching the parchment pattern to a sturdy, curved pillow and placing pins along a section of the design. By twisting and braiding individual threads—both ends of which were wound onto a pair of bobbins and looped over these pins—she produced a variety of stitches, inserting additional pins to secure her progress as she worked. The complexity of the design determined the number of bobbins required.

1897

Cotton, paper, metal, and wood

Textilmuseum St. Gallen, 40017

Photo: Michael Rast

Before 1882

Paper, cotton, and linen

Textilmuseum St. Gallen, 00077.1–9

Photo: Michael Rast

Early Lace

The forerunner of “true” needle lace was openwork—various types of embroidery on white linen in which threads are manipulated or removed from the woven fabric and the resulting angular openings are decorated with needlework. Bobbin lace developed from a convergence of increasingly elaborate multistrand braiding techniques and is made by winding individual threads around cylindrical bobbins and interlacing them to create an endless variety of patterns. Needle and bobbin laces of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries adopted the geometric shapes of openwork embroidery and, like openwork, often embellished household and personal linens in the form of inserts or edgings.

1630–70

Linen

Textilmuseum St. Gallen, Gift of Leopold Iklé, 1908, 20135

From lacemaking cities on the Italian peninsula including Venice, Milan, and Genoa, needle- and bobbin-lace techniques spread throughout Europe. These were further developed by upper-class women, who had the time and money to devote to making their own lace. Increasing demand led to the gradual development of a cottage industry employing thousands of women from Europe’s lower classes. The Southern Netherlands was a particularly important region for lace production and Antwerp was the main trading center where male and female merchants sold Flemish lace on an international market.

Operating outside the guild system, lacemakers often toiled long hours under difficult conditions, working under supervisors who could be either men or women. These intermediaries provided the lacemakers with materials and negotiated their (generally low) wages that represented a fraction of the cost of the time-consuming final piece. Nonetheless, lacemaking offered laboring-class women the opportunity to earn money.

Lace and Printed Textile Pattern Books

Printed textile pattern books emerged in central Europe in the early sixteenth century, with one of the first examples published by Johannes Schönsperger the Younger in 1524 in Zwickau, Germany. From the 1540s on, books containing designs for openwork and needle and bobbin laces proliferated across Europe, particularly on the Italian peninsula. Over one hundred of these books were published between 1524 and 1600.

Pattern books usually comprised a frontispiece, a preface, and a series of plates. Many included dedications to wealthy female patronesses, thereby aligning lacemaking with virtue and nobility. We know the names of many individuals who designed and printed lace pattern books. On the Italian peninsula, Isabella Catanea Parasole (ca. 1565/1570–ca. 1625) was one of the first female printmakers to publish lace designs under her own name, and the five pattern books published by Bartolomeo Danieli (active 1610–1643) show his knowledge of book printing and lace design, gained from working in both industries.

Lacemakers used these books directly. It is possible to match surviving pieces of lace and openwork to specific designs. Some publications explain how to transfer patterns to other surfaces for use, such as by tracing or removing the pages and pricking them with pins. A lack of instructions alongside the pattern plates suggests that authors knew their audiences were familiar with lacemaking techniques.

Click Image to Enlarge

Published by Agostino Parisini (Italian, active 1625–1637) and Giovanni Battista Negroponte (Italian, active ca. 1633– ), Bologna

1639

Etching

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1937, 37.47.2 (1–13)