SIGHTLINES presents new modes of displaying and viewing African art and material culture. At the heart of the presentation are a group of historical metalworks from sub-Saharan Africa, drawn from the traveling exhibition Peace, Power & Prestige: Metal Arts in Africa, organized by Susan Cooksey, formerly of the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art in Gainesville, Florida. We are honored to host these emissaries from the past, appreciate the responses of visitors who have encountered them in this and other institutions, and recognize the scholarship that has accompanied them.

In order to contribute to ongoing conversations about how museums exhibit African art, we must do more than celebrate the beauty of these metalworks and share their rich histories. We also need to consider the ethics of how we view and care for these works and our obligations toward the communities connected to them. For this reason, we have chosen to center the profound and generative relationship between historical African arts and material culture and the work of contemporary artists. Rather than exhibit these two realms separately, we embrace their connections and the dynamic kinship between past and present.

Here, we offer pairings of historical objects with art by thirteen contemporary makers working in relation to the African continent or Black Diaspora. We have introduced these pairings with seven themes to reflect the diverse material worlds that the artworks inhabit: EXTRACTION, SPECULATIVE ARCHITECTURE, CURRENCY, DEVOTION, EMBODYING POWER, DOMESTICITY, and PROTECTION. Please treat these connections as invitations to envision your own sightlines through the exhibition.

SIGHTLINES presents new modes of displaying and viewing African art and material culture. At the heart of the presentation are a group of historical metalworks from sub-Saharan Africa, drawn from the traveling exhibition Peace, Power & Prestige: Metal Arts in Africa, organized by Susan Cooksey, formerly of the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art in Gainesville, Florida. We are honored to host these emissaries from the past, appreciate the responses of visitors who have encountered them in this and other institutions, and recognize the scholarship that has accompanied them.

In order to contribute to ongoing conversations about how museums exhibit African art, we must do more than celebrate the beauty of these metalworks and share their rich histories. We also need to consider the ethics of how we view and care for these works and our obligations toward the communities connected to them. For this reason, we have chosen to center the profound and generative relationship between historical African arts and material culture and the work of contemporary artists. Rather than exhibit these two realms separately, we embrace their connections and the dynamic kinship between past and present.

Here, we offer pairings of historical objects with art by thirteen contemporary makers working in relation to the African continent or Black Diaspora. We have introduced these pairings with seven themes to reflect the diverse material worlds that the artworks inhabit: EXTRACTION, SPECULATIVE ARCHITECTURE, CURRENCY, DEVOTION, EMBODYING POWER, DOMESTICITY, and PROTECTION. Please treat these connections as invitations to envision your own sightlines through the exhibition.

COLONIAL

NARRATIVES

Histories of extraction materialize in people’s lives in ways that are great and small. Otobong Nkanga’s monumental tapestry tells a story of how violent colonial histories of mineral extraction scarred African landscapes. Who will control and benefit from these resources in the future? This textile is marked with lines that resemble a map’s topographic contours or constellations on a star chart. Our extractive desires stretch not just across landscapes, but extend beyond the earth itself.

Brass mrammuo (gold weights, plural form of abrammuo), used by Akan peoples to measure gold dust, often took forms that served storytelling traditions. Their designs integrated materials and iconography associated with historical events, including colonialism and mineral extraction. This tiny gold weight, from the period of British colonization of what is now Ghana, resembles a folding chair used by settlers, right down to the chair’s characteristic brass tacks. Imbued with such resonances, this metalwork tells a story that was passed on through generations.

Histories of extraction materialize in people’s lives in ways that are great and small. Otobong Nkanga’s monumental tapestry tells a story of how violent colonial histories of mineral extraction scarred African landscapes. Who will control and benefit from these resources in the future? This textile is marked with lines that resemble a map’s topographic contours or constellations on a star chart. Our extractive desires stretch not just across landscapes, but extend beyond the earth itself.

Brass mrammuo (gold weights, plural form of abrammuo), used by Akan peoples to measure gold dust, often took forms that served storytelling traditions. Their designs integrated materials and iconography associated with historical events, including colonialism and mineral extraction. This tiny gold weight, from the period of British colonization of what is now Ghana, resembles a folding chair used by settlers, right down to the chair’s characteristic brass tacks. Imbued with such resonances, this metalwork tells a story that was passed on through generations.

INTERCULTURAL

JOURNEYS

The sixteen hand-painted wooden planks by Lubaina Himid function like a stage design, evoking a ship’s hull to convey the experience of a journey between continents. Decorating the planks are an intercultural array of sea shells, plants, marine animals, and vessels that symbolize the movement of people, materials, and ideas across oceans. African metalworks and their iconography also made such journeys: in the form of their skilled makers, often enslaved; as treasured reminders of home and family; and in the possession of collectors.

Tacks made from brass, a metal imported to Africa from Europe, adorn the elongated wooden handle of this iron axe and associate it with colonial-era trade. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Teke rulers of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo incorporated imported and native metals as well as intercultural symbols into their regalia to signal their political influence and economic networks. Although made of metal from afar, this ceremonial axe, which likely functioned as the ruler’s insignia, was made by a metalsmith who lived in close proximity to his king, perhaps even participating in his investiture rites.

The sixteen hand-painted wooden planks by Lubaina Himid function like a stage design, evoking a ship’s hull to convey the experience of a journey between continents. Decorating the planks are an intercultural array of sea shells, plants, marine animals, and vessels that symbolize the movement of people, materials, and ideas across oceans. African metalworks and their iconography also made such journeys: in the form of their skilled makers, often enslaved; as treasured reminders of home and family; and in the possession of collectors.

Tacks made from brass, a metal imported to Africa from Europe, adorn the elongated wooden handle of this iron axe and associate it with colonial-era trade. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Teke rulers of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo incorporated imported and native metals as well as intercultural symbols into their regalia to signal their political influence and economic networks. Although made of metal from afar, this ceremonial axe, which likely functioned as the ruler’s insignia, was made by a metalsmith who lived in close proximity to his king, perhaps even participating in his investiture rites.

CONCEALED

WORLDS

What might a material tell us about people’s experience of colonialism and independence in Africa? When the plant Agave sisalana (sisal) was introduced to Tanzania in 1893, its cultivation sparked European settlement. In the mid-twentieth century, the production and export of this crop underwrote Tanzania’s independence from Europe. Sisal is a robust fiber used in carpets and twine, but here it is a cloudlike fleece, soft to the touch. Kapwani Kiwanga’s installation presents the plant in its raw state, as laborers would have encountered it, adding an experiential dimension to this complex history.

The gold from which this xirsi (porte Qur’an bracelet) is made arrived in what is now Somalia via international trade routes across the Indian Ocean in the nineteenth century. Given to a woman at the time of marriage, it was a portable form of wealth and a display of status. Concealed within the capsule, however, was something that offered a different kind of protection: a sacred text from the Qur’an. Porte Qur’an bracelets were occasionally embellished with bells that added another sensory element.

What might a material tell us about people’s experience of colonialism and independence in Africa? When the plant Agave sisalana (sisal) was introduced to Tanzania in 1893, its cultivation sparked European settlement. In the mid-twentieth century, the production and export of this crop underwrote Tanzania’s independence from Europe. Sisal is a robust fiber used in carpets and twine, but here it is a cloudlike fleece, soft to the touch. Kapwani Kiwanga’s installation presents the plant in its raw state, as laborers would have encountered it, adding an experiential dimension to this complex history.

The gold from which this xirsi (porte Qur’an bracelet) is made arrived in what is now Somalia via international trade routes across the Indian Ocean in the nineteenth century. Given to a woman at the time of marriage, it was a portable form of wealth and a display of status. Concealed within the capsule, however, was something that offered a different kind of protection: a sacred text from the Qur’an. Porte Qur’an bracelets were occasionally embellished with bells that added another sensory element.

SILENCE AND

ERASURE

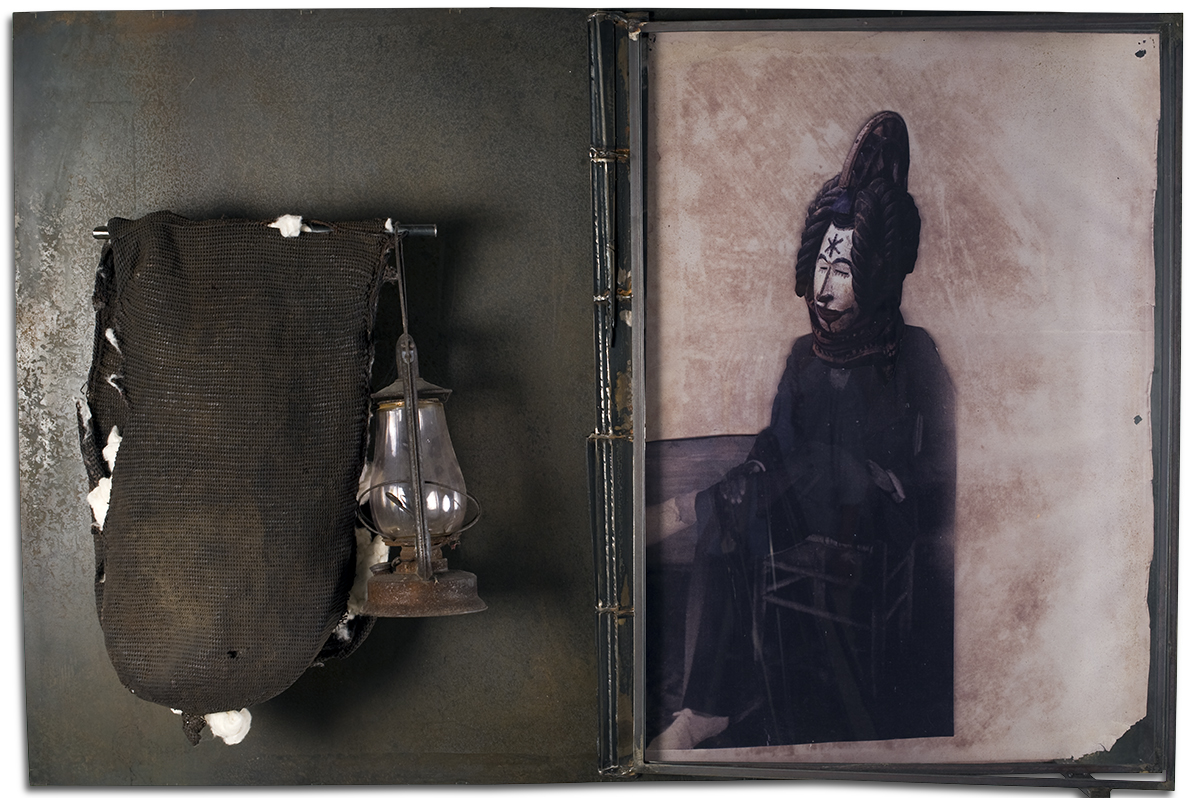

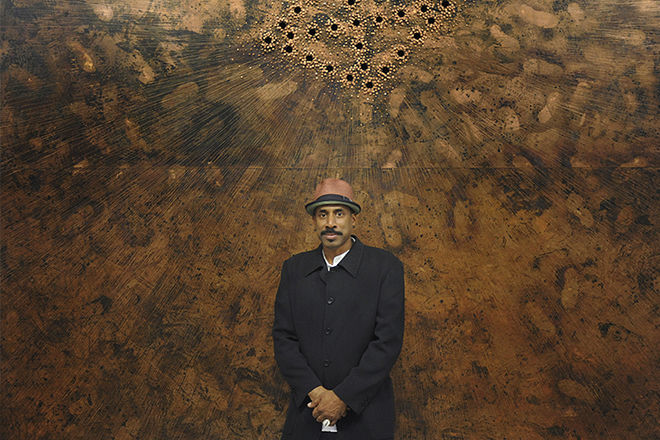

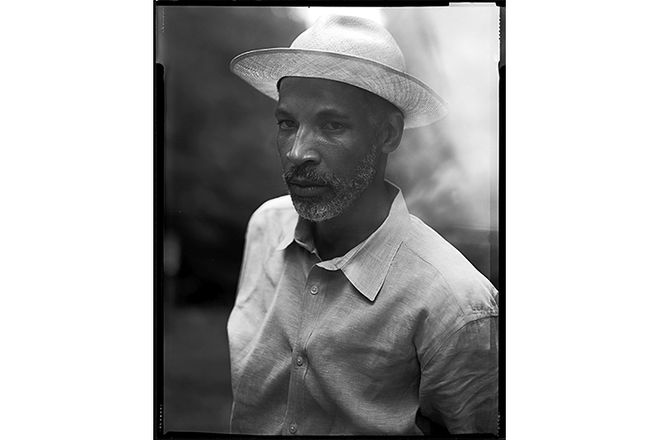

Objects, like oral traditions of storytelling, are portals for voices silenced in other kinds of historical evidence. In this assemblage, Radcliffe Bailey presents artifacts speaking to his own family’s stories of their enslaved ancestors’ journeys to freedom: a lantern, a bag of cotton, and a photograph inherited from his grandmother. Together, these objects form a storybook that honors the artist’s family and opens up a space for other families and communities to remember their own journeys.

This bronze bell has an elaborately cast human face but no voice—without a clapper, it cannot ring. The chemical composition of the metal, facial features and markings, hairstyle, and other decorative elements indicate that it was made in what is now Nigeria sometime before the sixteenth century. The many other bells that survive from this time and place suggest that their makers and owners inhabited a rich and varied soundscape, but such experiences elude historical documentation.

Objects, like oral traditions of storytelling, are portals for voices silenced in other kinds of historical evidence. In this assemblage, Radcliffe Bailey presents artifacts speaking to his own family’s stories of their enslaved ancestors’ journeys to freedom: a lantern, a bag of cotton, and a photograph inherited from his grandmother. Together, these objects form a storybook that honors the artist’s family and opens up a space for other families and communities to remember their own journeys.

This bronze bell has an elaborately cast human face but no voice—without a clapper, it cannot ring. The chemical composition of the metal, facial features and markings, hairstyle, and other decorative elements indicate that it was made in what is now Nigeria sometime before the sixteenth century. The many other bells that survive from this time and place suggest that their makers and owners inhabited a rich and varied soundscape, but such experiences elude historical documentation.

ENVISIONING

VALUE

Since the seventeenth century, tulips have symbolized speculative bubbles, the excessive economic valuation of certain commodities. Amanda Williams’s tulip bulbs— cast in cement and coated with imitation gold leaf—are positioned on the floor of the gallery, creating a barrier that the visitor must navigate. This work extends from her larger body of public art installations, highlighting the ways in which people move through racialized spaces such as redlined neighborhoods.

Spirals and twists are a common aesthetic feature of historical currencies in West and Central Africa. This technically difficult, delicate, double-spiral form was clearly made by a highly skilled blacksmith who twisted the metal while forging it to create a wrapping effect. While this object had commercial exchange value, the visual form of the double spiral also circulated on metalworks that were not considered currency.

Since the seventeenth century, tulips have symbolized speculative bubbles, the excessive economic valuation of certain commodities. Amanda Williams’s tulip bulbs— cast in cement and coated with imitation gold leaf—are positioned on the floor of the gallery, creating a barrier that the visitor must navigate. This work extends from her larger body of public art installations, highlighting the ways in which people move through racialized spaces such as redlined neighborhoods.

Spirals and twists are a common aesthetic feature of historical currencies in West and Central Africa. This technically difficult, delicate, double-spiral form was clearly made by a highly skilled blacksmith who twisted the metal while forging it to create a wrapping effect. While this object had commercial exchange value, the visual form of the double spiral also circulated on metalworks that were not considered currency.

HONORING

THE BODY

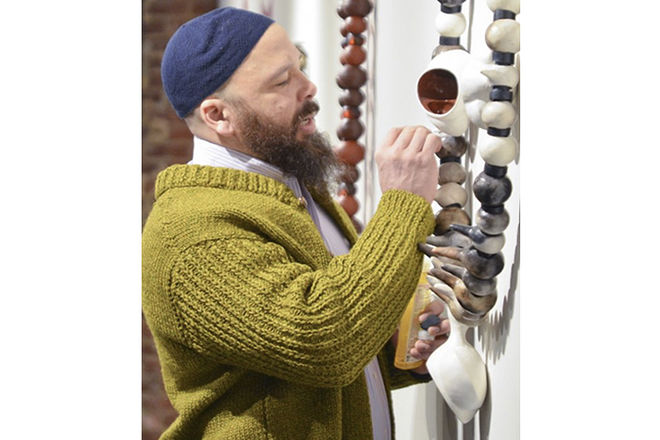

Sharif Bey creates each of the ceramic beads of this huge, necklace-shaped sculpture by hand, employing the ancient pinch technique that was typically used in the making of pots. As a form, the beaded necklace has rich cultural associations, including African and African American ritual and political practices of adornment and devotion. Yet, because this piece is so large, it exceeds its ornamental function, acting as an elaborate frame—perhaps even a halo—for its viewer.

The figure depicted on this copper alloy bracelet represents a setõn, a spirit “other” who guides humans through life. Healers would wear such bracelets to visually communicate their divine status and power. They also encouraged their spiritual followers to wear similar forms of jewelry. Artisans played their part in such devotional practices by designing ornate and lifelike objects to appease the spirits.

Sharif Bey creates each of the ceramic beads of this huge, necklace-shaped sculpture by hand, employing the ancient pinch technique that was typically used in the making of pots. As a form, the beaded necklace has rich cultural associations, including African and African American ritual and political practices of adornment and devotion. Yet, because this piece is so large, it exceeds its ornamental function, acting as an elaborate frame—perhaps even a halo—for its viewer.

The figure depicted on this copper alloy bracelet represents a setõn, a spirit “other” who guides humans through life. Healers would wear such bracelets to visually communicate their divine status and power. They also encouraged their spiritual followers to wear similar forms of jewelry. Artisans played their part in such devotional practices by designing ornate and lifelike objects to appease the spirits.

RELICS AND

MEMORY

By encasing found objects in bronze, including a tire and tennis shoes, Nari Ward crafts a tire swing, memorializing one of the joys of childhood. This rendering also carries histories of suffering and violence: the rope from which the swing hangs is tied in a noose; tires were used in retributive “necklacings” during South Africa’s apartheid era. Like the African American slave hymn with which it shares its name, Swing Low materializes a life condition whereby one is constantly surrounded by the threat of death while holding fast to the promise of heaven and salvation.

This brass figure would have guarded the bones of an ancestor. The preservation of these relics, which were encased in copper wire and placed within a basket, served to protect the power of the deceased and ensure the success of their living family. It was especially important to honor ancestors in times of crisis. The figure’s gleaming red-and-yellow surfaces cast their own reflective light, which can be both blinding and revelatory for an observer.

By encasing found objects in bronze, including a tire and tennis shoes, Nari Ward crafts a tire swing, memorializing one of the joys of childhood. This rendering also carries histories of suffering and violence: the rope from which the swing hangs is tied in a noose; tires were used in retributive “necklacings” during South Africa’s apartheid era. Like the African American slave hymn with which it shares its name, Swing Low materializes a life condition whereby one is constantly surrounded by the threat of death while holding fast to the promise of heaven and salvation.

This brass figure would have guarded the bones of an ancestor. The preservation of these relics, which were encased in copper wire and placed within a basket, served to protect the power of the deceased and ensure the success of their living family. It was especially important to honor ancestors in times of crisis. The figure’s gleaming red-and-yellow surfaces cast their own reflective light, which can be both blinding and revelatory for an observer.

Curator Drew Thompson discusses Nari Ward’s “Swing Low.”

ANCESTRAL

CONNECTIONS

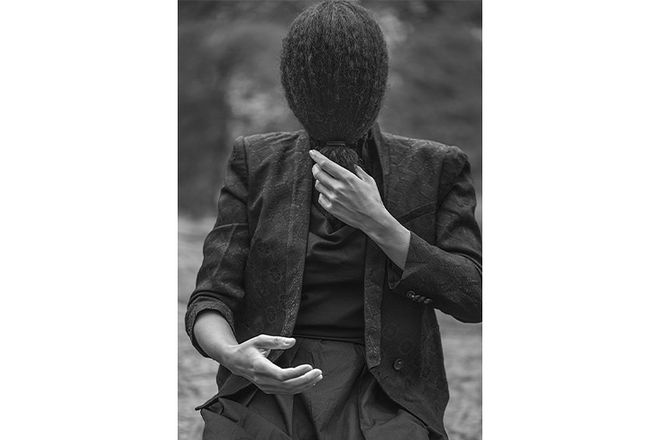

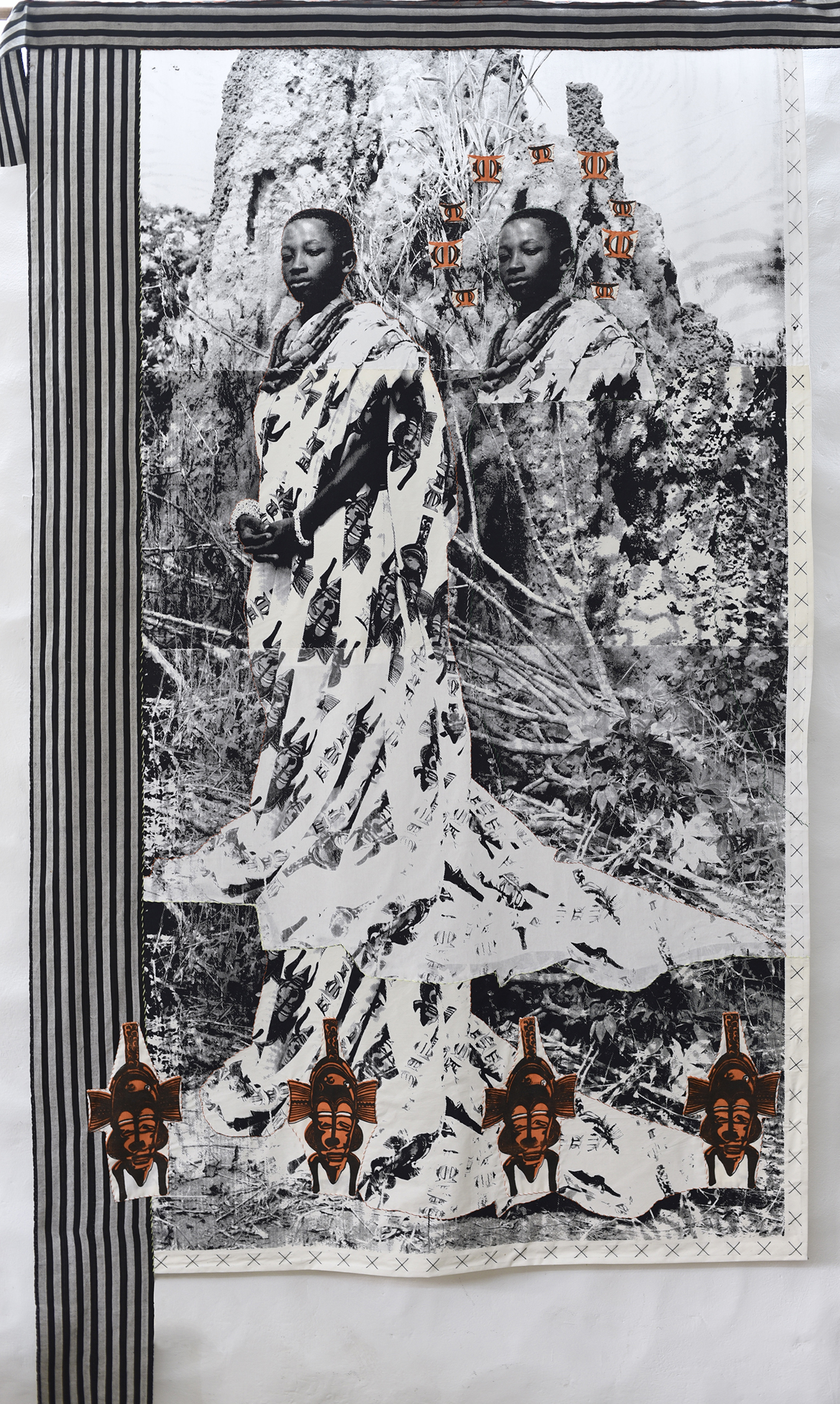

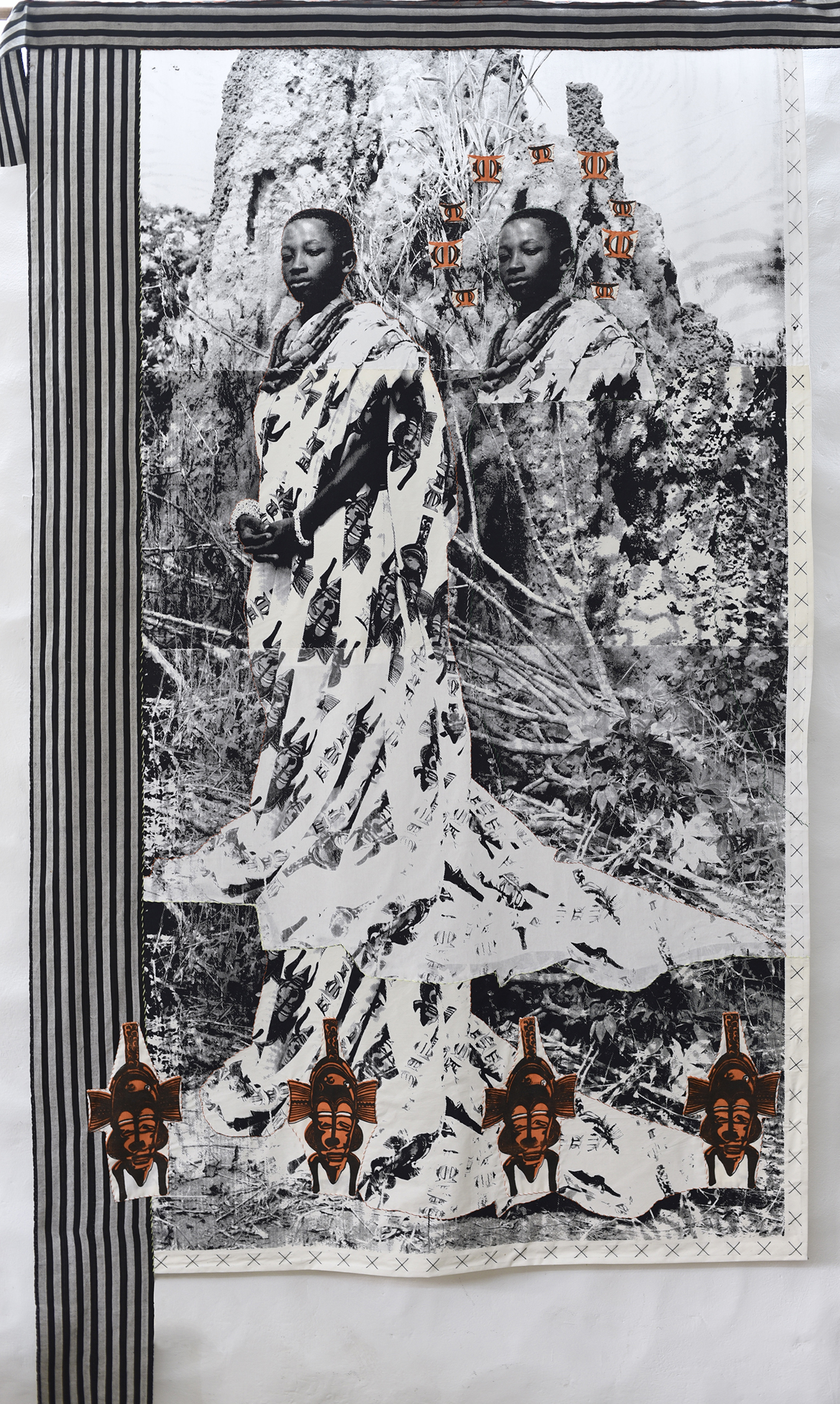

In Ghanaian culture, kente cloth denotes chiefly status and is produced in a vast array of colors and patterns. Zohra Opoku inherited a kente cloth from her father, whom she met only later in his life, along with many family photographs after his death. In Bob’s Cloth, she uses these materials to forge a connection with her ancestors and family in Ghana. This textile illustrates the powerful way that historical objects and images circulate and travel to represent Africa for those in the Black Diaspora.

The Lobi peoples, who have lived in Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire since the late eighteenth century, commissioned brass figures like this one to honor deceased family members and seek good fortune from their ancestors. Gestures are an important part of Lobi spiritual ceremonies, and these objects are likewise highly expressive. The seated posture of this particular figure indicates that it was intended to keep reverent vigil over a shrine or house.

In Ghanaian culture, kente cloth denotes chiefly status and is produced in a vast array of colors and patterns. Zohra Opoku inherited a kente cloth from her father, whom she met only later in his life, along with many family photographs after his death. In Bob’s Cloth, she uses these materials to forge a connection with her ancestors and family in Ghana. This textile illustrates the powerful way that historical objects and images circulate and travel to represent Africa for those in the Black Diaspora.

The Lobi peoples, who have lived in Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire since the late eighteenth century, commissioned brass figures like this one to honor deceased family members and seek good fortune from their ancestors. Gestures are an important part of Lobi spiritual ceremonies, and these objects are likewise highly expressive. The seated posture of this particular figure indicates that it was intended to keep reverent vigil over a shrine or house.

Zohra Opoku (b. 1976, Germany), Bob’s Cloth, 2017. Screenprint on canvas, thread, acrylic, elements from an original print from the 1970s, and Kente cloth, with photograph and photographic film. Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, courtesy of Mariane Ibrahaim.

VISION AND

MOBILITY

Julia Phillips’s binoculars resemble those used on observation decks to view distant landscapes. The fleshy quality of the eye piece reminds us that looking is an embodied action. Placed against the gallery wall, the work frustrates our desire to be unobserved observers of the other artworks on display. Viewers are asked to acknowledge the historical metalworks as having their own vantage points on history.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, unmarried girls and women of Igbo culture (in present-day Nigeria) wore these elaborate brass anklets, called adalà or ogba, to convey their status and the wealth of their families. From the moment that they were fitted, these ornaments immobilized their wearers and could permanently affect how their bodies developed. If we exhibit such objects for their aesthetics alone, then we neglect the experience of their wearers, effectively making their bodies invisible.

Julia Phillips’s binoculars resemble those used on observation decks to view distant landscapes. The fleshy quality of the eye piece reminds us that looking is an embodied action. Placed against the gallery wall, the work frustrates our desire to be unobserved observers of the other artworks on display. Viewers are asked to acknowledge the historical metalworks as having their own vantage points on history.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, unmarried girls and women of Igbo culture (in present-day Nigeria) wore these elaborate brass anklets, called adalà or ogba, to convey their status and the wealth of their families. From the moment that they were fitted, these ornaments immobilized their wearers and could permanently affect how their bodies developed. If we exhibit such objects for their aesthetics alone, then we neglect the experience of their wearers, effectively making their bodies invisible.

CARING

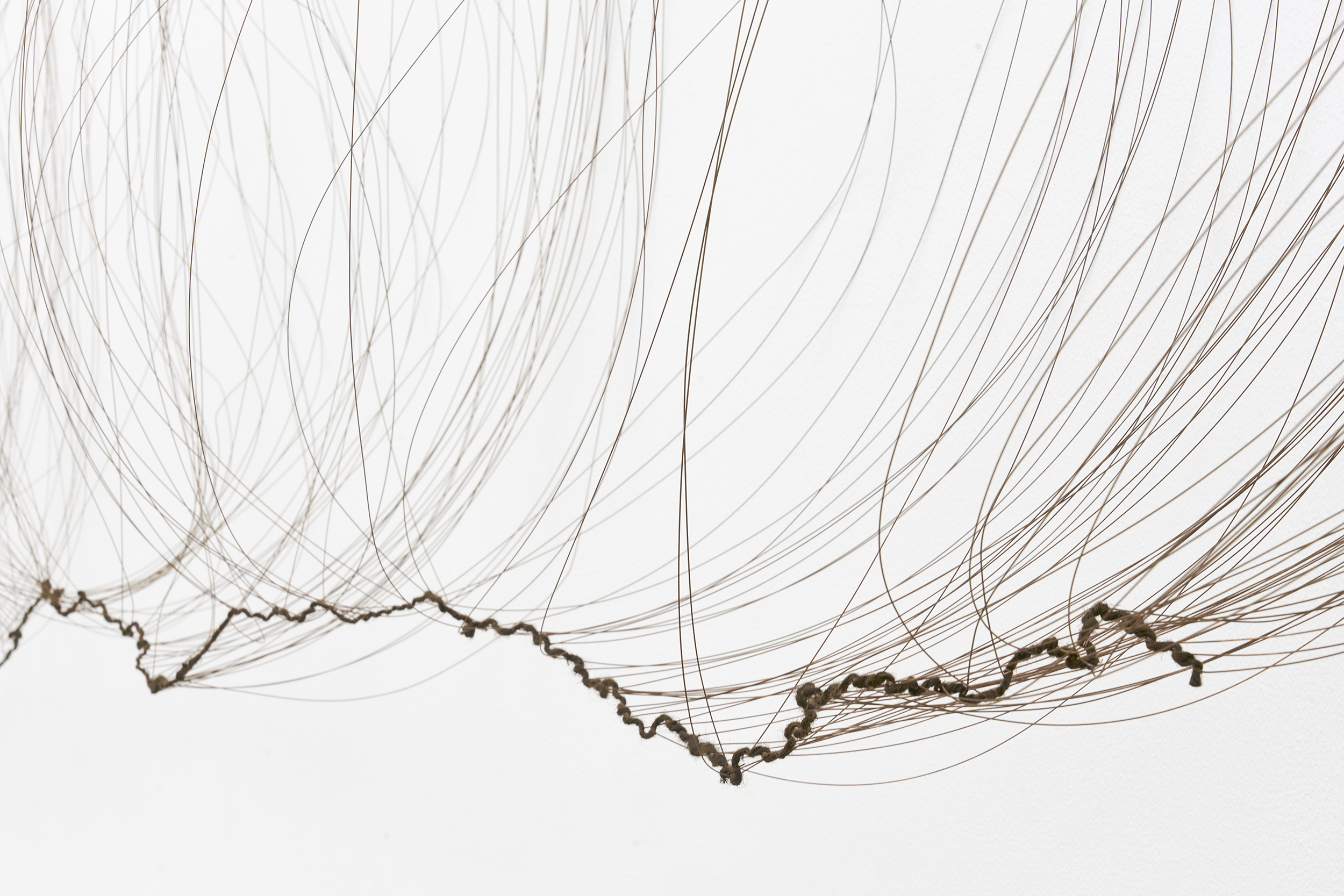

Using hemp twine and copper-coated wire, Bronwyn Katz creates the appearance of a veil of water cascading down the wall. Within the domestic space of our homes, water seems an unremarkable, ever-present substance. But represented on the gallery wall, it becomes something more elusive and vital: a repository of memory, an exercise in care for ourselves and the earth, and an element of Indigenous systems of knowledge.

Objects housed in domestic spaces can shape our lives in significant ways. This brass pendant, seemingly an object of adornment, is actually a locus of power. It is a part of the Indigenous knowledge of the Jula or Gouin people of present-day Burkina Faso. Inhabiting both land and water, the turtle is considered a swift messenger to the spiritual world. Diviners advised people to display such objects to appease the spirits and create safe, orderly spaces for living.

Using hemp twine and copper-coated wire, Bronwyn Katz creates the appearance of a veil of water cascading down the wall. Within the domestic space of our homes, water seems an unremarkable, ever-present substance. But represented on the gallery wall, it becomes something more elusive and vital: a repository of memory, an exercise in care for ourselves and the earth, and an element of Indigenous systems of knowledge.

Objects housed in domestic spaces can shape our lives in significant ways. This brass pendant, seemingly an object of adornment, is actually a locus of power. It is a part of the Indigenous knowledge of the Jula or Gouin people of present-day Burkina Faso. Inhabiting both land and water, the turtle is considered a swift messenger to the spiritual world. Diviners advised people to display such objects to appease the spirits and create safe, orderly spaces for living.

LIVING WITH

BEAUTY

A “slow burn” is a lasting love, a sensation of home. Abigail Lucien creates sculptural works inspired by the domestic architectures of Cap-Haïten, where she grew up. This elegant, twisted-metal handrailing, embellished with flames and stars, signals social mobility within a context of ancestral traditions. Lucien’s work draws from and harks back to the practices of enslaved African metalsmiths, who used their knowledge of complex forging and casting techniques to create monuments on the lands of their displacement across the Americas.

There are few silver mines in Africa. The metal used to make this container was likely sourced from merchants in what are now Ethiopia and Somalia, or from melted-down coins known as Maria Theresa thaler, minted in Austria. Throughout East Africa, opulent silver adornments and personal objects were given to brides by their mothers and grandmothers as a form of financial protection. This container held kohl, a pigment for the eyes that served to beautify the wearer and ward off evil spirits.

A “slow burn” is a lasting love, a sensation of home. Abigail Lucien creates sculptural works inspired by the domestic architectures of Cap-Haïten, where she grew up. This elegant, twisted-metal handrailing, embellished with flames and stars, signals social mobility within a context of ancestral traditions. Lucien’s work draws from and harks back to the practices of enslaved African metalsmiths, who used their knowledge of complex forging and casting techniques to create monuments on the lands of their displacement across the Americas.

There are few silver mines in Africa. The metal used to make this container was likely sourced from merchants in what are now Ethiopia and Somalia, or from melted-down coins known as Maria Theresa thaler, minted in Austria. Throughout East Africa, opulent silver adornments and personal objects were given to brides by their mothers and grandmothers as a form of financial protection. This container held kohl, a pigment for the eyes that served to beautify the wearer and ward off evil spirits.

TRANSNATIONAL

SOLIDARITIES

The mirrored embellishments on Tsedaye Makonnen’s Astral Sea series of cloth works are remnants cut from her light boxes, which are also on display in this exhibition. The blue-black textiles symbolize the journeys that African populations made across the Mediterranean. This particular cloth’s design resembles that of the tafà gašša (Amharic for “shield”). Historical and contemporary travelers alike, Makonnen suggests, experience and require protection from violence.

Changes in the way that shields are used over time reflect transformations in the nature of threats that necessitate protection. This ornate Abyssinian brass-and-hide shield originated as a marker of a boy’s transition to adulthood. In the late nineteenth century, Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia, armed war captives with a less-ornate version of this circular decorated shield. The use of guns in Ethiopia’s war with Italy quickly made such shields ineffective. Rather than disappear, tafà gašša became a prestigious form of regalia and Menelik II gifted one to King George V of Britain on the occasion of his 1911 coronation.

The mirrored embellishments on Tsedaye Makonnen’s Astral Sea series of cloth works are remnants cut from her light boxes, which are also on display in this exhibition. The blue-black textiles symbolize the journeys that African populations made across the Mediterranean. This particular cloth’s design resembles that of the tafà gašša (Amharic for “shield”). Historical and contemporary travelers alike, Makonnen suggests, experience and require protection from violence.

Changes in the way that shields are used over time reflect transformations in the nature of threats that necessitate protection. This ornate Abyssinian brass-and-hide shield originated as a marker of a boy’s transition to adulthood. In the late nineteenth century, Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia, armed war captives with a less-ornate version of this circular decorated shield. The use of guns in Ethiopia’s war with Italy quickly made such shields ineffective. Rather than disappear, tafà gašša became a prestigious form of regalia and Menelik II gifted one to King George V of Britain on the occasion of his 1911 coronation.

COLONIAL

NARRATIVES

Histories of extraction materialize in people’s lives in ways that are great and small. Otobong Nkanga’s monumental tapestry tells a story of how violent colonial histories of mineral extraction scarred African landscapes. Who will control and benefit from these resources in the future? This textile is marked with lines that resemble a map’s topographic contours or constellations on a star chart. Our extractive desires stretch not just across landscapes, but extend beyond the earth itself.

Brass mrammuo (gold weights, plural form of abrammuo), used by Akan peoples to measure gold dust, often took forms that served storytelling traditions. Their designs integrated materials and iconography associated with historical events, including colonialism and mineral extraction. This tiny gold weight, from the period of British colonization of what is now Ghana, resembles a folding chair used by settlers, right down to the chair’s characteristic brass tacks. Imbued with such resonances, this metalwork tells a story that was passed on through generations.

Histories of extraction materialize in people’s lives in ways that are great and small. Otobong Nkanga’s monumental tapestry tells a story of how violent colonial histories of mineral extraction scarred African landscapes. Who will control and benefit from these resources in the future? This textile is marked with lines that resemble a map’s topographic contours or constellations on a star chart. Our extractive desires stretch not just across landscapes, but extend beyond the earth itself.

Brass mrammuo (gold weights, plural form of abrammuo), used by Akan peoples to measure gold dust, often took forms that served storytelling traditions. Their designs integrated materials and iconography associated with historical events, including colonialism and mineral extraction. This tiny gold weight, from the period of British colonization of what is now Ghana, resembles a folding chair used by settlers, right down to the chair’s characteristic brass tacks. Imbued with such resonances, this metalwork tells a story that was passed on through generations.

INTERCULTURAL

JOURNEYS

The sixteen hand-painted wooden planks by Lubaina Himid function like a stage design, evoking a ship’s hull to convey the experience of a journey between continents. Decorating the planks are an intercultural array of sea shells, plants, marine animals, and vessels that symbolize the movement of people, materials, and ideas across oceans. African metalworks and their iconography also made such journeys: in the form of their skilled makers, often enslaved; as treasured reminders of home and family; and in the possession of collectors.

Tacks made from brass, a metal imported to Africa from Europe, adorn the elongated wooden handle of this iron axe and associate it with colonial-era trade. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Teke rulers of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo incorporated imported and native metals as well as intercultural symbols into their regalia to signal their political influence and economic networks. Although made of metal from afar, this ceremonial axe, which likely functioned as the ruler’s insignia, was made by a metalsmith who lived in close proximity to his king, perhaps even participating in his investiture rites.

The sixteen hand-painted wooden planks by Lubaina Himid function like a stage design, evoking a ship’s hull to convey the experience of a journey between continents. Decorating the planks are an intercultural array of sea shells, plants, marine animals, and vessels that symbolize the movement of people, materials, and ideas across oceans. African metalworks and their iconography also made such journeys: in the form of their skilled makers, often enslaved; as treasured reminders of home and family; and in the possession of collectors.

Tacks made from brass, a metal imported to Africa from Europe, adorn the elongated wooden handle of this iron axe and associate it with colonial-era trade. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Teke rulers of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo incorporated imported and native metals as well as intercultural symbols into their regalia to signal their political influence and economic networks. Although made of metal from afar, this ceremonial axe, which likely functioned as the ruler’s insignia, was made by a metalsmith who lived in close proximity to his king, perhaps even participating in his investiture rites.

CONCEALED

WORLDS

What might a material tell us about people’s experience of colonialism and independence in Africa? When the plant Agave sisalana (sisal) was introduced to Tanzania in 1893, its cultivation sparked European settlement. In the mid-twentieth century, the production and export of this crop underwrote Tanzania’s independence from Europe. Sisal is a robust fiber used in carpets and twine, but here it is a cloudlike fleece, soft to the touch. Kapwani Kiwanga’s installation presents the plant in its raw state, as laborers would have encountered it, adding an experiential dimension to this complex history.

The gold from which this xirsi (porte Qur’an bracelet) is made arrived in what is now Somalia via international trade routes across the Indian Ocean in the nineteenth century. Given to a woman at the time of marriage, it was a portable form of wealth and a display of status. Concealed within the capsule, however, was something that offered a different kind of protection: a sacred text from the Qur’an. Porte Qur’an bracelets were occasionally embellished with bells that added another sensory element.

What might a material tell us about people’s experience of colonialism and independence in Africa? When the plant Agave sisalana (sisal) was introduced to Tanzania in 1893, its cultivation sparked European settlement. In the mid-twentieth century, the production and export of this crop underwrote Tanzania’s independence from Europe. Sisal is a robust fiber used in carpets and twine, but here it is a cloudlike fleece, soft to the touch. Kapwani Kiwanga’s installation presents the plant in its raw state, as laborers would have encountered it, adding an experiential dimension to this complex history.

The gold from which this xirsi (porte Qur’an bracelet) is made arrived in what is now Somalia via international trade routes across the Indian Ocean in the nineteenth century. Given to a woman at the time of marriage, it was a portable form of wealth and a display of status. Concealed within the capsule, however, was something that offered a different kind of protection: a sacred text from the Qur’an. Porte Qur’an bracelets were occasionally embellished with bells that added another sensory element.

SILENCE AND

ERASURE

Objects, like oral traditions of storytelling, are portals for voices silenced in other kinds of historical evidence. In this assemblage, Radcliffe Bailey presents artifacts speaking to his own family’s stories of their enslaved ancestors’ journeys to freedom: a lantern, a bag of cotton, and a photograph inherited from his grandmother. Together, these objects form a storybook that honors the artist’s family and opens up a space for other families and communities to remember their own journeys.

This bronze bell has an elaborately cast human face but no voice—without a clapper, it cannot ring. The chemical composition of the metal, facial features and markings, hairstyle, and other decorative elements indicate that it was made in what is now Nigeria sometime before the sixteenth century. The many other bells that survive from this time and place suggest that their makers and owners inhabited a rich and varied soundscape, but such experiences elude historical documentation.

Objects, like oral traditions of storytelling, are portals for voices silenced in other kinds of historical evidence. In this assemblage, Radcliffe Bailey presents artifacts speaking to his own family’s stories of their enslaved ancestors’ journeys to freedom: a lantern, a bag of cotton, and a photograph inherited from his grandmother. Together, these objects form a storybook that honors the artist’s family and opens up a space for other families and communities to remember their own journeys.

This bronze bell has an elaborately cast human face but no voice—without a clapper, it cannot ring. The chemical composition of the metal, facial features and markings, hairstyle, and other decorative elements indicate that it was made in what is now Nigeria sometime before the sixteenth century. The many other bells that survive from this time and place suggest that their makers and owners inhabited a rich and varied soundscape, but such experiences elude historical documentation.

ENVISIONING

VALUE

Since the seventeenth century, tulips have symbolized speculative bubbles, the excessive economic valuation of certain commodities. Amanda Williams’s tulip bulbs— cast in cement and coated with imitation gold leaf—are positioned on the floor of the gallery, creating a barrier that the visitor must navigate. This work extends from her larger body of public art installations, highlighting the ways in which people move through racialized spaces such as redlined neighborhoods.

Spirals and twists are a common aesthetic feature of historical currencies in West and Central Africa. This technically difficult, delicate, double-spiral form was clearly made by a highly skilled blacksmith who twisted the metal while forging it to create a wrapping effect. While this object had commercial exchange value, the visual form of the double spiral also circulated on metalworks that were not considered currency.

Since the seventeenth century, tulips have symbolized speculative bubbles, the excessive economic valuation of certain commodities. Amanda Williams’s tulip bulbs— cast in cement and coated with imitation gold leaf—are positioned on the floor of the gallery, creating a barrier that the visitor must navigate. This work extends from her larger body of public art installations, highlighting the ways in which people move through racialized spaces such as redlined neighborhoods.

Spirals and twists are a common aesthetic feature of historical currencies in West and Central Africa. This technically difficult, delicate, double-spiral form was clearly made by a highly skilled blacksmith who twisted the metal while forging it to create a wrapping effect. While this object had commercial exchange value, the visual form of the double spiral also circulated on metalworks that were not considered currency.

HONORING

THE BODY

Sharif Bey creates each of the ceramic beads of this huge, necklace-shaped sculpture by hand, employing the ancient pinch technique that was typically used in the making of pots. As a form, the beaded necklace has rich cultural associations, including African and African American ritual and political practices of adornment and devotion. Yet, because this piece is so large, it exceeds its ornamental function, acting as an elaborate frame—perhaps even a halo—for its viewer.

The figure depicted on this copper alloy bracelet represents a setõn, a spirit “other” who guides humans through life. Healers would wear such bracelets to visually communicate their divine status and power. They also encouraged their spiritual followers to wear similar forms of jewelry. Artisans played their part in such devotional practices by designing ornate and lifelike objects to appease the spirits.

Sharif Bey creates each of the ceramic beads of this huge, necklace-shaped sculpture by hand, employing the ancient pinch technique that was typically used in the making of pots. As a form, the beaded necklace has rich cultural associations, including African and African American ritual and political practices of adornment and devotion. Yet, because this piece is so large, it exceeds its ornamental function, acting as an elaborate frame—perhaps even a halo—for its viewer.

The figure depicted on this copper alloy bracelet represents a setõn, a spirit “other” who guides humans through life. Healers would wear such bracelets to visually communicate their divine status and power. They also encouraged their spiritual followers to wear similar forms of jewelry. Artisans played their part in such devotional practices by designing ornate and lifelike objects to appease the spirits.

RELICS AND

MEMORY

By encasing found objects in bronze, including a tire and tennis shoes, Nari Ward crafts a tire swing, memorializing one of the joys of childhood. This rendering also carries histories of suffering and violence: the rope from which the swing hangs is tied in a noose; tires were used in retributive “necklacings” during South Africa’s apartheid era. Like the African American slave hymn with which it shares its name, Swing Low materializes a life condition whereby one is constantly surrounded by the threat of death while holding fast to the promise of heaven and salvation.

This brass figure would have guarded the bones of an ancestor. The preservation of these relics, which were encased in copper wire and placed within a basket, served to protect the power of the deceased and ensure the success of their living family. It was especially important to honor ancestors in times of crisis. The figure’s gleaming red-and-yellow surfaces cast their own reflective light, which can be both blinding and revelatory for an observer.

By encasing found objects in bronze, including a tire and tennis shoes, Nari Ward crafts a tire swing, memorializing one of the joys of childhood. This rendering also carries histories of suffering and violence: the rope from which the swing hangs is tied in a noose; tires were used in retributive “necklacings” during South Africa’s apartheid era. Like the African American slave hymn with which it shares its name, Swing Low materializes a life condition whereby one is constantly surrounded by the threat of death while holding fast to the promise of heaven and salvation.

This brass figure would have guarded the bones of an ancestor. The preservation of these relics, which were encased in copper wire and placed within a basket, served to protect the power of the deceased and ensure the success of their living family. It was especially important to honor ancestors in times of crisis. The figure’s gleaming red-and-yellow surfaces cast their own reflective light, which can be both blinding and revelatory for an observer.

Curator Drew Thompson discusses Nari Ward’s “Swing Low.”

ANCESTRAL

CONNECTIONS

In Ghanaian culture, kente cloth denotes chiefly status and is produced in a vast array of colors and patterns. Zohra Opoku inherited a kente cloth from her father, whom she met only later in his life, along with many family photographs after his death. In Bob’s Cloth, she uses these materials to forge a connection with her ancestors and family in Ghana. This textile illustrates the powerful way that historical objects and images circulate and travel to represent Africa for those in the Black Diaspora.

The Lobi peoples, who have lived in Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire since the late eighteenth century, commissioned brass figures like this one to honor deceased family members and seek good fortune from their ancestors. Gestures are an important part of Lobi spiritual ceremonies, and these objects are likewise highly expressive. The seated posture of this particular figure indicates that it was intended to keep reverent vigil over a shrine or house.

In Ghanaian culture, kente cloth denotes chiefly status and is produced in a vast array of colors and patterns. Zohra Opoku inherited a kente cloth from her father, whom she met only later in his life, along with many family photographs after his death. In Bob’s Cloth, she uses these materials to forge a connection with her ancestors and family in Ghana. This textile illustrates the powerful way that historical objects and images circulate and travel to represent Africa for those in the Black Diaspora.

The Lobi peoples, who have lived in Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire since the late eighteenth century, commissioned brass figures like this one to honor deceased family members and seek good fortune from their ancestors. Gestures are an important part of Lobi spiritual ceremonies, and these objects are likewise highly expressive. The seated posture of this particular figure indicates that it was intended to keep reverent vigil over a shrine or house.

Zohra Opoku (b. 1976, Germany), Bob’s Cloth, 2017. Screenprint on canvas, thread, acrylic, elements from an original print from the 1970s, and Kente cloth, with photograph and photographic film. Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, courtesy of Mariane Ibrahaim.

VISION AND

MOBILITY

Julia Phillips’s binoculars resemble those used on observation decks to view distant landscapes. The fleshy quality of the eye piece reminds us that looking is an embodied action. Placed against the gallery wall, the work frustrates our desire to be unobserved observers of the other artworks on display. Viewers are asked to acknowledge the historical metalworks as having their own vantage points on history.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, unmarried girls and women of Igbo culture (in present-day Nigeria) wore these elaborate brass anklets, called adalà or ogba, to convey their status and the wealth of their families. From the moment that they were fitted, these ornaments immobilized their wearers and could permanently affect how their bodies developed. If we exhibit such objects for their aesthetics alone, then we neglect the experience of their wearers, effectively making their bodies invisible.

Julia Phillips’s binoculars resemble those used on observation decks to view distant landscapes. The fleshy quality of the eye piece reminds us that looking is an embodied action. Placed against the gallery wall, the work frustrates our desire to be unobserved observers of the other artworks on display. Viewers are asked to acknowledge the historical metalworks as having their own vantage points on history.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, unmarried girls and women of Igbo culture (in present-day Nigeria) wore these elaborate brass anklets, called adalà or ogba, to convey their status and the wealth of their families. From the moment that they were fitted, these ornaments immobilized their wearers and could permanently affect how their bodies developed. If we exhibit such objects for their aesthetics alone, then we neglect the experience of their wearers, effectively making their bodies invisible.

CARING

Using hemp twine and copper-coated wire, Bronwyn Katz creates the appearance of a veil of water cascading down the wall. Within the domestic space of our homes, water seems an unremarkable, ever-present substance. But represented on the gallery wall, it becomes something more elusive and vital: a repository of memory, an exercise in care for ourselves and the earth, and an element of Indigenous systems of knowledge.

Objects housed in domestic spaces can shape our lives in significant ways. This brass pendant, seemingly an object of adornment, is actually a locus of power. It is a part of the Indigenous knowledge of the Jula or Gouin people of present-day Burkina Faso. Inhabiting both land and water, the turtle is considered a swift messenger to the spiritual world. Diviners advised people to display such objects to appease the spirits and create safe, orderly spaces for living.

Using hemp twine and copper-coated wire, Bronwyn Katz creates the appearance of a veil of water cascading down the wall. Within the domestic space of our homes, water seems an unremarkable, ever-present substance. But represented on the gallery wall, it becomes something more elusive and vital: a repository of memory, an exercise in care for ourselves and the earth, and an element of Indigenous systems of knowledge.

Objects housed in domestic spaces can shape our lives in significant ways. This brass pendant, seemingly an object of adornment, is actually a locus of power. It is a part of the Indigenous knowledge of the Jula or Gouin people of present-day Burkina Faso. Inhabiting both land and water, the turtle is considered a swift messenger to the spiritual world. Diviners advised people to display such objects to appease the spirits and create safe, orderly spaces for living.

LIVING WITH

BEAUTY

A “slow burn” is a lasting love, a sensation of home. Abigail Lucien creates sculptural works inspired by the domestic architectures of Cap-Haïten, where she grew up. This elegant, twisted-metal handrailing, embellished with flames and stars, signals social mobility within a context of ancestral traditions. Lucien’s work draws from and harks back to the practices of enslaved African metalsmiths, who used their knowledge of complex forging and casting techniques to create monuments on the lands of their displacement across the Americas.

There are few silver mines in Africa. The metal used to make this container was likely sourced from merchants in what are now Ethiopia and Somalia, or from melted-down coins known as Maria Theresa thaler, minted in Austria. Throughout East Africa, opulent silver adornments and personal objects were given to brides by their mothers and grandmothers as a form of financial protection. This container held kohl, a pigment for the eyes that served to beautify the wearer and ward off evil spirits.

A “slow burn” is a lasting love, a sensation of home. Abigail Lucien creates sculptural works inspired by the domestic architectures of Cap-Haïten, where she grew up. This elegant, twisted-metal handrailing, embellished with flames and stars, signals social mobility within a context of ancestral traditions. Lucien’s work draws from and harks back to the practices of enslaved African metalsmiths, who used their knowledge of complex forging and casting techniques to create monuments on the lands of their displacement across the Americas.

There are few silver mines in Africa. The metal used to make this container was likely sourced from merchants in what are now Ethiopia and Somalia, or from melted-down coins known as Maria Theresa thaler, minted in Austria. Throughout East Africa, opulent silver adornments and personal objects were given to brides by their mothers and grandmothers as a form of financial protection. This container held kohl, a pigment for the eyes that served to beautify the wearer and ward off evil spirits.

TRANSNATIONAL

SOLIDARITIES

The mirrored embellishments on Tsedaye Makonnen’s Astral Sea series of cloth works are remnants cut from her light boxes, which are also on display in this exhibition. The blue-black textiles symbolize the journeys that African populations made across the Mediterranean. This particular cloth’s design resembles that of the tafà gašša (Amharic for “shield”). Historical and contemporary travelers alike, Makonnen suggests, experience and require protection from violence.

Changes in the way that shields are used over time reflect transformations in the nature of threats that necessitate protection. This ornate Abyssinian brass-and-hide shield originated as a marker of a boy’s transition to adulthood. In the late nineteenth century, Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia, armed war captives with a less-ornate version of this circular decorated shield. The use of guns in Ethiopia’s war with Italy quickly made such shields ineffective. Rather than disappear, tafà gašša became a prestigious form of regalia and Menelik II gifted one to King George V of Britain on the occasion of his 1911 coronation.

The mirrored embellishments on Tsedaye Makonnen’s Astral Sea series of cloth works are remnants cut from her light boxes, which are also on display in this exhibition. The blue-black textiles symbolize the journeys that African populations made across the Mediterranean. This particular cloth’s design resembles that of the tafà gašša (Amharic for “shield”). Historical and contemporary travelers alike, Makonnen suggests, experience and require protection from violence.

Changes in the way that shields are used over time reflect transformations in the nature of threats that necessitate protection. This ornate Abyssinian brass-and-hide shield originated as a marker of a boy’s transition to adulthood. In the late nineteenth century, Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia, armed war captives with a less-ornate version of this circular decorated shield. The use of guns in Ethiopia’s war with Italy quickly made such shields ineffective. Rather than disappear, tafà gašša became a prestigious form of regalia and Menelik II gifted one to King George V of Britain on the occasion of his 1911 coronation.