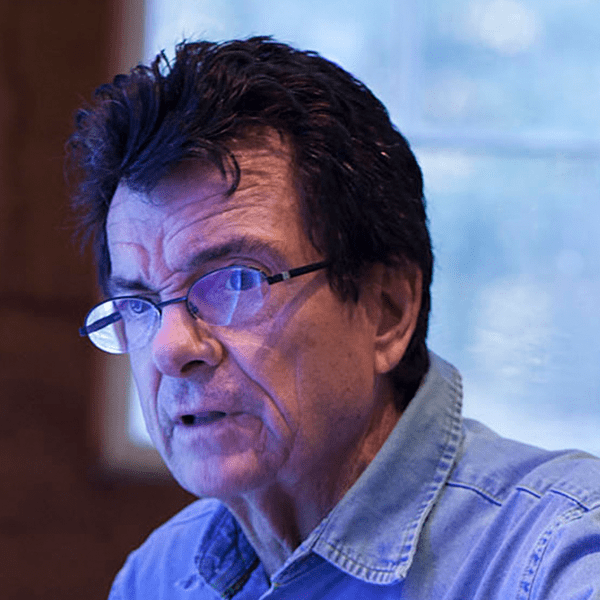

Dan Dailey talks about his time at Venini and his tripod-form works in a recording for Paul Hollister (c. 1989–1990).

.

07:40Dan Dailey talks about his time at Venini and his tripod-form works in a recording for Paul Hollister (c. 1989–1990). Dan Dailey Interview for Paul Hollister, c. 1989-1990 (Rakow title: Dan Dailey self-interview [sound recording] / for Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168376) Clip length: 07:40.

Time stamp: 00:00

Clip 1: Dan Dailey talks about Dale Chihuly’s visits to Italy as inspiration for work at Venini and reminisces about Ludovico Diaz di Santillana. Clip length: 03:39.

Dan Dailey: I’ve been thinking about it, the subject of my work at Venini and those times for me and other people, and what got me to go to Italy in the first place was on one hand a suggestion from [Dale] Chihuly, who was my teacher at RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] when I was a graduate student. I was his first graduate student—so when I was in school, Chihuly told me that he had gone to Italy and worked, I don’t know how much work he did there, but he really enjoyed his time there, and it made a lasting impression on him. He’s been going back and forth to Venice ever since. But the idea intrigued me, and I had already been entertaining a notion of moving to Europe for a period before I ever went to graduate school, so it just sort of fell in with my thinking, and I applied for a Fulbright grant through RISD and eventually I got the award, and then time came and I moved over there. When I went to Venini, Mr. Santillana [Ludovico Diaz di Santillana] was extremely receptive, he really was a very hospitable man—he died recently. I don’t know if you knew him or not. He was quite a person. I’ll tell you a couple interesting things about Santillana. I remember one night we were walking on the street, it was about one o’clock in the morning in Venice, and it was a winter night, not too cold, but a rainy sort of dreary night, very, very dark. And we were standing on this bridge or standing on some balcony or something and sort of looking at this cityscape, and there was a man sort of passing by in the shadows a little distance away. You could see him but you couldn’t hear him, and Ludovigo said, ‘Here’s the mark of a true gentleman, he’s got rubber soled shoes.’ Now I’m not saying that was a profound remark, that’s just a characteristic remark of Ludovigo Diaz di Santillana. And another thing I remember, he’s a hell of a driver, a hell of a driver, he had this Citroen—the DX, or DS, it wasn’t a Maserati, it was just DS. And we went on this business trip one day, and Santillana was speeding along, came to a rotary in the highway, and as we went around the rotary, this woman in some little Italian hotrod cut us off, passed on the inside of the curve. He started swearing in I don’t know what languages, and he was absolutely furious. He stepped on the gas and we chased that lady [background noise (gear shift) audible] maybe half an hour out of our way [DD’s car likely stopped at this point] to catch up with her. I don’t remember if he ever did, but he was an interesting character. I was sorry to hear that he died.

Time stamp: 03:42

Clip 2: Dan Dailey relays a story about Ludovico Diaz di Santillana of Venini reacting to the lamps he designed for them. Clip length: 01:56.

Dan Dailey: I had a nice group of lamps, and they actually in a funny way looked like Venini product because it was their colors, their materials, but the style was really my own. And I remember Santillana came in for a critique one day, near the end of the time that I was staying there, and I had this room all set up with the lights on and everything, and it looked pretty good. He walked around the room for a while, and he obviously was amused by it, he was smiling and he liked the pieces and he turned them off and on and he was playing with them and then he started smacking his forehead just, ‘These are mad, these are mad pieces,’ and he had these English expressions, I think he learned his English in England. But he just kept on saying, ‘These are mad pieces, it’ll never work for Venini,’ and it’s right, it never worked for Venini. So, in a way, without realizing it, I didn’t pay enough attention to Venini’s style and try to incorporate myself in that sense. All I did was I went there and I went to Italian showrooms and looked at fantastic contemporary Italian design in the time I was there, which was 1972. And I was highly influenced by the playful, energetic quality of Italian design. And all my pieces were a response to it, and they were lamps that worked. So I thought, ‘Well, Venini might be able to do this.’ But as it turned out, it wasn’t Venini, it didn’t look like Venini. And despite the diversity of all the efforts of artists who worked with Venini, there is a Venini look. A very definite Venini look. And my look was not the Venini look.

Time stamp: 05:41

Clip 3: Dan Dailey talks about his tripod forms being inspired by Shang bronzes. Clip length: 01:59.

Dan Dailey: The work at Venini—I made a lot of things with tripod and odd symmetry. The tripods came out of an interest in Shang bronzes because of those very interesting forms, you know, like they used the gourd shape or other natural forms as a basis for their bronze forms. And maybe they even used actual fruits to cast the bronze with that method of casting that they had, a little bit like a ceramic shell casting, really interesting technology that was developed in the most crude ways, but very sophisticated results. But I always liked those shapes, especially that tripod form, and, of course, it became very popular with a lot of ceramicists during the seventies. And they’re still making kind of pseudo-oriental work, a lot of American crafts people. But the tripod form, to me, was interesting because of the way it affected the symmetry of the object. Because many times when you view a vase, especially a Greek vase, it’s bi-symmetrical, even though it’s a piece in the round it’s kind of a bi-symmetrical object. And the bronze—the tripod form comes from—it really does make you view it in the round, it makes you aware of the other side of the piece in a different way.