Lucia is a young nun living in a Venetian convent in the middle of the seventeenth century. In addition to her religious duties, she is engaged in making point de Venise needle lace, which at this time is the most luxurious and desirable type of lace throughout Europe. Lucia is the second daughter of a wealthy family who have consigned her to the convent rather than pay an expensive dowry to a potential husband.

Lacemaking is one of the skills expected of a daughter from an elite family like Lucia’s. She has been learning needlework techniques since she was very young, practicing her skills diligently, knowing that they would benefit her in her adult life. For Lucia, lacemaking demonstrates the industriousness and seriousness expected of a nun, and even though she cannot leave her convent, it means she can earn a small amount of her own money.

Click on the tabs to learn more about Lucia’s life.

Family Life

As the daughter of a wealthy and well-connected Venetian family, Lucia’s childhood was a privileged one. Her older sister, Lidia, was a beauty and a social butterfly. Her younger brother, Marco, constantly got into trouble and liked nothing more than to scare his sisters by releasing a mouse in their bedroom. They were a close family, but as the quiet younger sister, Lucia was often overlooked. The announcement of her sister’s engagement, when Lucia was fifteen years old, determined her future. Her parents informed her that she was to become a nun, regardless of her own inclinations towards the church.

Matthaeus Merian, Venetia. M. Merian, Franckfurt am Mayn, 1638. Copperplate engraving. Album / British Library / Alamy Stock Photo, R56YJ9 (RM).

In seventeenth-century Venice, it was common practice for daughters from upper-class families to be compelled by their parents to join convents. Providing an adequate dowry for a marriageable daughter was essential to establishing key familial alliances. Many families could afford this large expense only once, and they sent the other daughters to convents.

Although far less extravagant than the feasts and ceremonies that were obligatory for a wedding and dowry, the celebrations for committing a daughter to a convent were lavish, involving special attire, foods, and rituals. Once they had entered the convent, nuns were not permitted to leave. Family members were free to visit them, but nuns could only communicate with the outside world through written letters.

Lace Education

Although Lucia dislikes the restrictions imposed by religious life and misses her family and its privileges, the convent is a familiar place to her. Like many patrician families in Venice, her parents sent her and Lidia to be educated in a convent when they were ten years old. Here the girls were kept in a protected environment while they learned the skills appropriate for women of their class: singing, music, sewing, embroidery, and needle and bobbin lacemaking. These final skills became central to Lucia’s life when she entered the convent. Here, she is trained to produce point de Venise, the most desirable and expensive style of needle lace in mid-seventeenth century Europe. As a child she learned the techniques that are the basis of all needle lace: buttonhole stitch and its variations. Now she has mastered these skills, she creates a sampler to use as a point of reference.

Lacemaking and embroidery were deemed important skills for young girls of patrician families to learn, as they would continue to be useful whether they were married or joined a convent. Nuns who were particularly adept at needlework were valued by their convents not only because of the commercial work they could take on, but also because they could then play an important part in one of the convent’s other main duties, which was educating girls and young women in those same skills.

Learn about education by nuns in eighteenth-century Valenciennes here.

Local Industry

Surviving documents suggest that there were as many as 2,500 nuns in Venice’s convents, although we do not know how many of them were involved in lacemaking. Many different groups of women made lace: in addition to nuns in convents, there were workshops of professional lacemakers, including those located in the islands of Burano. Poor women also learned lacemaking as a part of their moral and professional education within charitable institutions such as the Casa delle Zittelle (Home for Unmarried Women), the Casa del Soccorso (Home for Repentant Sinners), and the Ospedale dei Derelitti (Asylum for Abandoned Women).

Jacopo Pontormo, Maria Salviati, 1537. Oil on panel. Uffizi, Florence. Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

Carlo Caliari, The Foundation of the Casa del Soccorso (altarpiece from the church of Santa Maria del Soccorso), 1595. Oil on canvas. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, 400. akg-images / Cameraphoto.

At these charitable institutions and among the professional lacemakers in Burano, there was usually a maestre (master) who communicated with the lace merchants who commissioned or purchased the finished lace. Lacemakers were forbidden from selling their own lace; typically they worked with intermediaries. In convents, it was often other nuns who supervised the making of lace and negotiated prices. Arcangela Tarabotti, a Venetian nun who criticized the church for its role in forcing women into convents, published accounts of her own work as an intermediary between clients and convent lacemakers. Her letters reveal that convent lacemakers worked on commission and, although the money they received would typically belong to the convent, it was also sometimes made available to the nuns for their personal expenses.

Techniques, Tools, and Materials

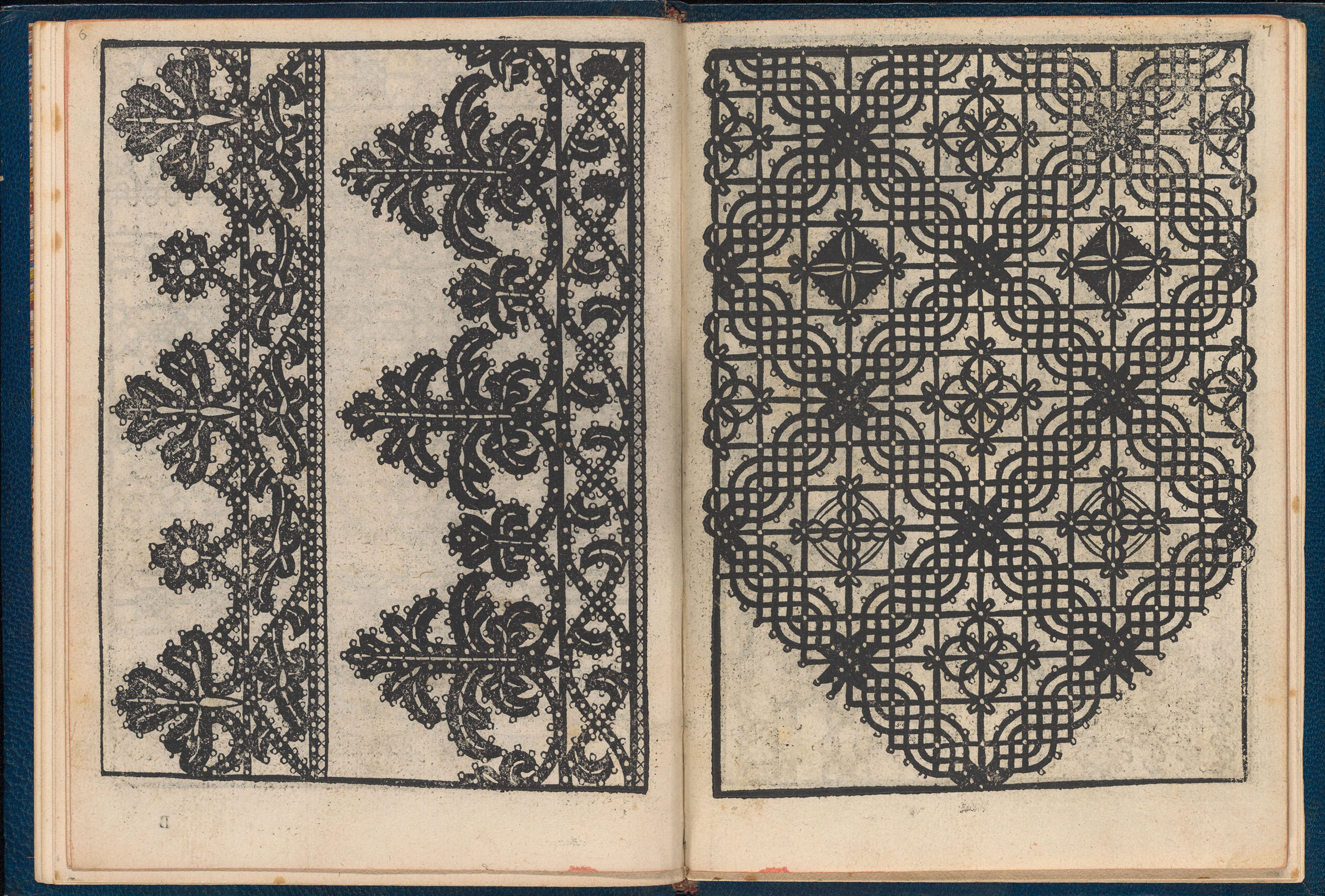

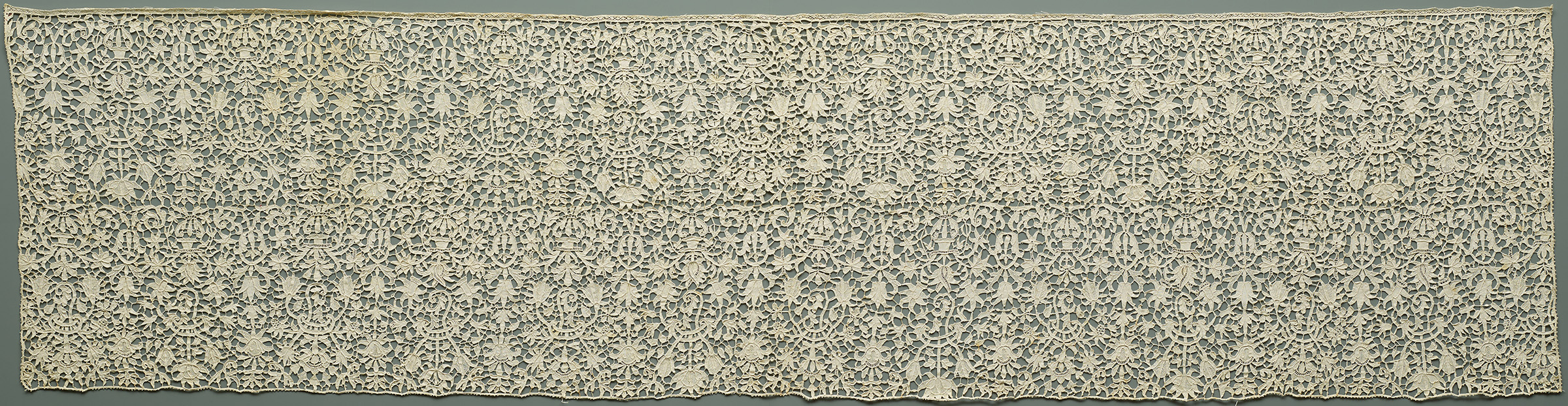

Both needle and bobbin lace were made in Venice in the seventeenth century. Needle lace, made using a single needle and thread, was known as punto in aria (point in the air). In the third quarter of the century, the luxuriant, sculptural, and extremely expensive point de Venise was sought after throughout Europe. Less renowned than this needle lace but still popular during the period was bobbin lace, called merletto, which was made by twisting pairs of threads wound around bobbins. Influential pattern books with designs for lace, such as the 1557 Le pompe, were published in Italy and central Europe from the mid-sixteenth to the early seventeenth century. Although not all surviving pattern books show signs of having been used, it is possible that nuns may have consulted them.

The Venetian mercers’ guild claimed the exclusive right to sell lace in the city. When the guild worked with institutional workshops or commercial lacemakers, they likely provided the raw materials, including linen, silver, or gold, on the condition that they would sell the finished lace. It is unclear how convent lacemakers, who operated outside of this system, obtained their materials, although they may have had to pay the mercers beforehand.

Punto in aria needle-lace border, Venice, 1630–50, reworked in the 19th century. Linen and cotton. Textilmuseum St. Gallen, Acquired from the Estate of John Jacoby, 1954, 00079.

Daily Life

Habit of Dominican Tertiary nun. S. J. Filippo Buonanni, Ordinum religiosorum in Ecclesiae Militantis catalogus/ Catalogo degli Ordini religiosi della Chiesa Militante, 2nd ed., 3 vols, vol. 2, no. 28. Published by Giorgio Placho, Rome, 1714. Engraving. Hathitrust.org, Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Life in a convent was strictly regulated. During their waking hours, nuns were not supposed to be idle and monastic rules governed the timing of prayers, meditation, and work. Lacemaking took place in either individual cells or communal workrooms. Seen as an economically productive activity, making lace was also deemed to be a virtuous way to occupy one’s mind and hands. While several nuns worked, another might read aloud from devotional literature. Meals were typically eaten collectively and the food was plain.

Follower of Alessandro Magnasco, Nuns at Work, first half of the 18th century. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982, 1982.60.13.

Click Image to Enlarge

Culture and Community

Lucia’s world is populated almost entirely by women. The community is close-knit, but isolated; Lucia is not allowed to leave the convent and any interaction with the outside world is tightly controlled. She may talk to female visitors through a grille, called a parlatorio, but only under the supervision of a chaperone. Gifts have to travel through a service wheel, called a ruota, to avoid physical contact. Letter-writing, even to her sister and mother, is discouraged.

However, because of the large number of nuns who had been confined against their will, Venetian convents were not always strict in enforcing their own rules. Some nuns wore lay clothing instead of habits and may have even worn lace themselves. Others performed in plays that gave the lay audience the opportunity to get a glimpse of the convent and allowed the nuns to temporarily inhabit lives and roles different from those that had been chosen for them.

Learn about the culture and community of lacemakers in Bedfordshire, England by clicking here.

Pietro Longhi, Il Parlatorio. The Visiting Parlor in the Convent. Oil on canvas. Ca’ Rezzonico, Museo del Settecento, Venice. Smith Archive / Alamy Stock Photo.

Although this painting is from the eighteenth century, it gives a sense of the convent parlatorio as a social space, with the lay visitors in the foreground and the nuns behind the metal grille.