Lace in American Portrait Photography, 1850–1900

Berthe Honoré Palmer

Left: Matthew J. Steffens, Portrait of Mrs. Bertha Honoré Palmer wearing the official gown, made by Worth of Paris, for the Paris Exposition, 1900. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-053133, Mathew J. Steffens photographer, 2374.

Right: House of Worth, Dress, Paris, 1900. Silk satin with cut velvet pattern, lace, ribbon, rhinestone. Chicago History Museum, Loan. Gift of Mrs. Potter Palmer II, 194.247. Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago. © Chicago Historical Society, published on or before 2017, all rights reserved.

Bertha Palmer, née Honoré (1849–1918), also known by her married name of Mrs. Potter Palmer, was a wealthy socialite and philanthropist. As the president of the Board of Lady Managers for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Palmer and her colleagues worked to showcase the achievements of American women on a world stage. With her husband, prominent Chicago businessman and real estate developer Mr. Potter Palmer (1826–1902), whom she married in 1871, Palmer amassed a legendary art collection including paintings by Mary Cassatt, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and others. These artworks now constitute the core of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Impressionist collection. Through this work, Palmer gained a reputation as a cultural leader and tastemaker. She cultivated a circle of politically powerful friends that included King Edward VII.

For the opening of the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900, Palmer commissioned a gown from the House of Worth. The combination of dramatic Art Nouveau flourishes and prominently featured handmade antique lace trimmings created a distinctly modern gown, which is preserved in the collection of the Chicago History Museum. Jean-Philippe Worth (1856–1926), founder of the House of Worth, was known for using only the finest materials in his couture creations. However, he also relied heavily on machine-made, chemical, and appliquéd lace, which during the period was inexpensive and therefore widely regarded as being of lesser quality. Despite the widespread popularity of these more affordable products, wealthy American consumers like Palmer insisted on wearing antique lace (often modified to correspond to contemporary fashions) to reinforce their identification with elite European women and to distinguish themselves from their middle-class counterparts, who relied on machine-made lace.

Well-Dressed Couple

The woman pictured on the right of this daguerreotype wears a black lace veil draped from the sides and back of her bonnet, a fashionable accessory throughout the nineteenth century in Europe and the United States. While the type of lace worn here is unidentifiable, machine-made lace was popular at this time, and could be easily purchased in a department store or, later in the century, from a mail-order catalogue. Lace veils were usually purchased as large squares and would be pinned either to the bonnet or into the wearer's hair. Nineteenth-century veil etiquette was strictly prescribed, with different styles purported to convey different information about the wearer’s age and social status. For example, the length of the veil typically corresponded to age; the longer the veil, the older the woman. In this photograph, the young woman’s veil—if pulled over her face—likely would have extended below her chin to her shoulders.

The nineteenth-century American fashion press urged women to wear lace veils as protection from air pollution and dust that might adversely affect their complexions. In a French health guide from 1855, doctors recommended women wear veils all year round, especially in the winter months, and asserted that white lace veils shielded the wearer not only from the sun but also from street dirt and dust. Fashionable women in both Europe and America followed this guidance to ensure that they remained looking youthful while navigating the harsh conditions of the outside world.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (American, 1862–1931) was one of the nation's most prominent civil rights advocates in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She spoke out and fought against sexism, racism, and, after several of her friends were murdered, lynching. She created several civil rights organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women.

During the last twenty years of her life, Wells dedicated much of her time to the women’s suffrage movement, advocating for the rights of African American women in particular, and paving the way for their future fight for civil rights. Wells received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 2020 for her brave reporting during the era of lynching.

Although by the late nineteenth century machine-made lace was widely available to middle-class consumers, it was still associated with status that derived from its historical connection with the wealth and privilege of white elites. Wells-Barnett’s frequent depiction wearing lace in photographs and drawings is a deliberate sartorial choice; in these two photographs, she demonstrates the same access and right to this luxury textile as her white peers. Here Wells-Barnett is wearing a collar of black Chantilly-style lace. This style of lace, which was at the height of its fashionability from about 1840 to 1870, could be either handmade or machine-made during this period and was available at various price points. By the mid-nineteenth century, lace machines were able to faithfully imitate complex handmade techniques, and it can be almost impossible to distinguish one from the other, particularly in a photograph. The volume and detail of Wells-Barnett’s collar suggest, however, that it may well have been quite expensive.

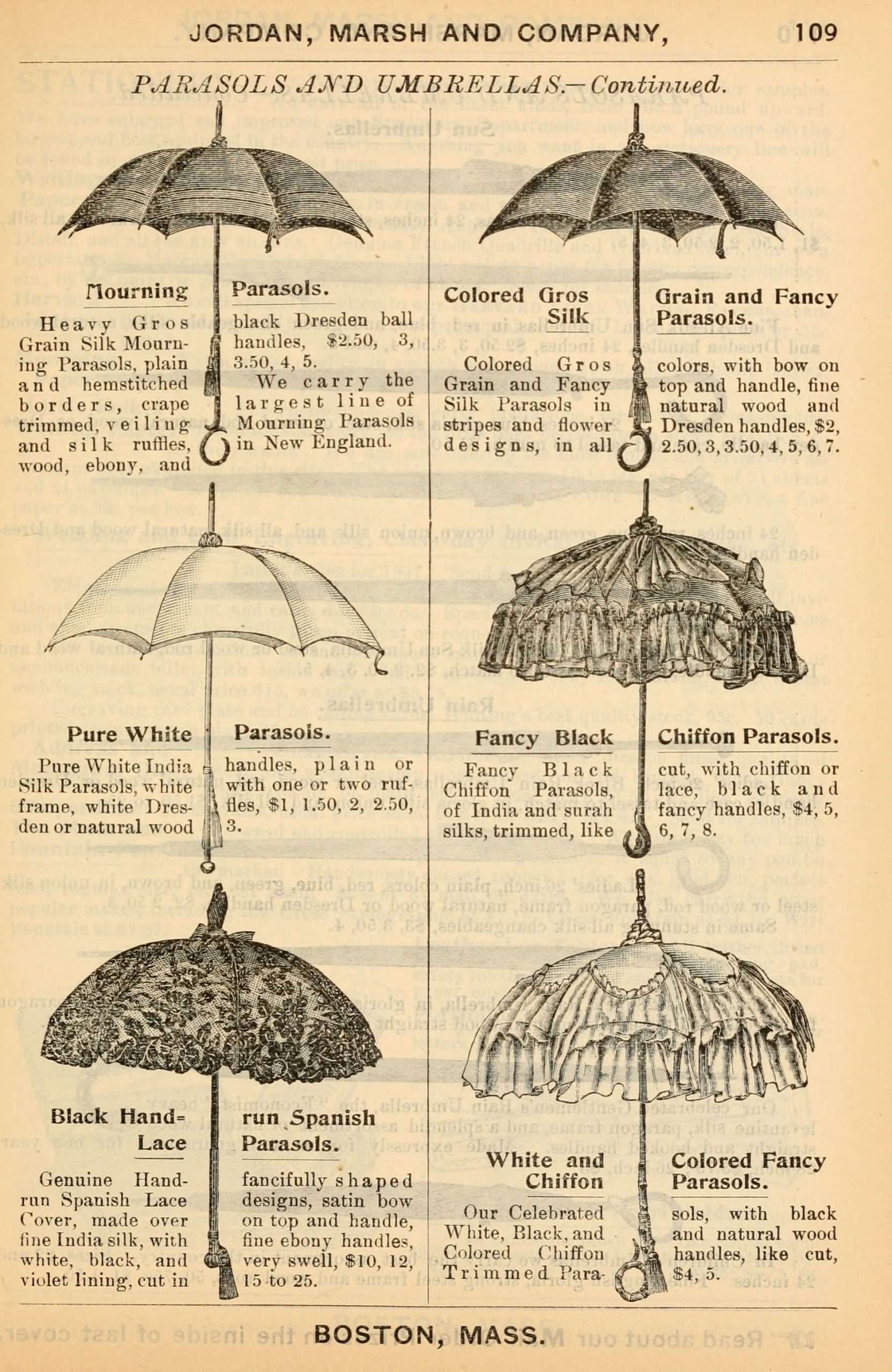

Lace Parasol

Against a studio backdrop, a young, unidentified African American woman poses with a parasol trimmed with a deep black lace border to have her photo taken by Orlando Scott Goff (American, 1843–1916) in Dickinson, North Dakota. Goff was a well-known photographer who established a studio in Bismarck, ND in 1873, and one in Dickinson between approximately 1891 and 1894.

In an 1897 price list from the Boston-based department store Jordan Marsh & Company, a “Black, Hand-run Spanish Lace Parasol” ranged in price from $10 to $25, while simpler models could be purchased for $2 to $5. For reference, a sewing machine set into an oak or walnut table cost $19 in the same catalog, while lengths of black lace range from 6 cents to $3 per yard. Dickinson is approximately 100 miles west of Bismarck, and at the end of the nineteenth century, would likely have been receiving most of its goods from East-coast-based companies like Jordan Marsh & Co. or Sears, Roebuck & Co.

C.C.P

The unidentified African American woman in this carte de visite, or photographic calling card, wears a bodice trimmed with what may be a reproduction of antique bobbin lace. Scalloped edges outline several areas of dense patterning, but no clear motif is discernible from the photograph. The last four decades of the nineteenth century saw a rise in re-creating and imitating popular sixteenth- and seventeenth-century styles of lace, including needle laces like point de Venise and bobbin laces made in England and Bohemia. Throughout the century, both the hand- and machine-lace industries experienced periods of volatility, which encouraged the use of valuable, status-affirming antique lace, retrieved from the family attic or purchased from lace dealers, and often refashioned to current taste. Although only affluent female consumers could afford the highly desirable antique laces, the mechanization of lace production allowed women of all but the poorest classes to wear lace of varying qualities.This was also a period when newly made fakes were flooding the market, and women had to carefully consider what they bought and and from whom they acquired their antique lace.

Actress Holding a Large Fan

During the nineteenth century, fans were fashionable feminine accessories meant to attract and arouse the opposite sex. Manipulation and movement of the fan was said to amplify desire by directing the gaze to a woman’s eyes, neck, chest and hands. Moreover, fans were believed to offer a secret means of communication between the sexes, with specific gestures associated with particular messages or sentiments. For example, touching the handle of the fan to one’s lips was an invitation to kiss while opening the fan wide meant “wait for me.” The subtlety of such movements created a shared intimacy and romance between lovers. When made of lace, fans were especially seductive: the textile simultaneously concealed and revealed the flirtatious figure behind the fan.

In the cigarette card pictured here, an actress poses with a large, black lace fan. Cigarette, or tobacco, cards first appeared in the 1870s as a means of stiffening the flimsy paper cigarette packages in order to protect their contents. Manufacturers quickly realized the marketing potential of these cards and began adding imagery and text to them. By issuing the cards in series of 25 to 50 different cards related to a common cultural theme, such as baseball players, tropical flowers, national flags, and stage actresses, manufacturers encouraged customers to buy more of the product to complete their collection. Cigarette cards thus became a clever way to boost sales and build brand loyalty.

The cigarette card featured here was distributed by the Baltimore-based Gale & Ax Tobacco Company in the late 1880s as part of the Actresses series. Holding a lace fan wide open behind her head, the actress draws on a variety of rich visual references. One wonders if the fan is meant to recall a halo, which frames her angelic face as her eyes gaze upwards to heaven. Alternatively, she may use the fan to emulate the flirtatious feathers of a peacock, inviting the viewer to participate in the game of courtship. Or perhaps the fan is intended to evoke the standing lace collars worn by monarchs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, thus communicating status and majesty. While we can only speculate about the model’s motivation for posing in such a way, any one of these interpretations is fitting given the context. Intended to be viewed by men whilst smoking, this photographic image draws on the close associations between lace fans and femininity to present the sitter as an object of desire.

Woman in Black-Silk Evening Dress

Photographers Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808–1901) catered to Boston’s elite. Their firm, Southworth & Hawes, was known for fine portrait daguerreotypes. This photographic process was quickly popularized after its introduction in the US in 1839. In 1846, the partners advertised “No CHEAP work done.” While other daguerreotype studios boasted the quantity of their products (sometimes hundreds of portraits daily for well under one dollar), Southworth & Hawes charged an average of $15 for one image. They referred to themselves as artists and claimed that their work allowed viewers to “see the [subject’s] inmost soul.”

Black lace was in vogue throughout the mid-nineteenth century. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ 1851 portrait of Madame Moitessier captures a similar black silhouette and lace shawl. Ingres’ precise brushwork captures a more elaborate eighteenth-century inspired lace pattern than the shawl captured in the daguerreotype.

Lady from Kent, Ohio

The identity of the woman in these two photographs is unknown, but her elegant lace-trimmed dress (especially visible in the first photograph) speaks to her comfortable social position, as does the fact that she had the means to be photographed numerous times. The invention of photography in 1839 allowed people to present themselves in new ways, including through through their clothing, bodily postures, and facial expressions. Around 1880, the photographic "cabinet card" became a popular way of creating and exchanging personal portraits, especially among the upper and middle classes in the United States. An increasing number of photography studios specialized in producing these cabinet cards that could be given or sent to family and friends, and were often collected in albums.

Photography sessions were expensive, and many participants could only afford one to take one portrait at a time. At the most exclusive studios, a dozen of these cards cost $6 around 1880, which is about $160 today. The woman in these photographs, however, not only purchased multiple cabinet cards, but she also wore a different dress accessorized with different lace for each sitting. In the first photograph, the deep lace border is an integral part of the large silk collar; in the second image, both the collar and sleeve caps are made entirely of lace. In addition to her wealth and social standing, these photographs reflect her individual taste; it is likely that she selected the garments and lace to present herself as she wished to be seen.

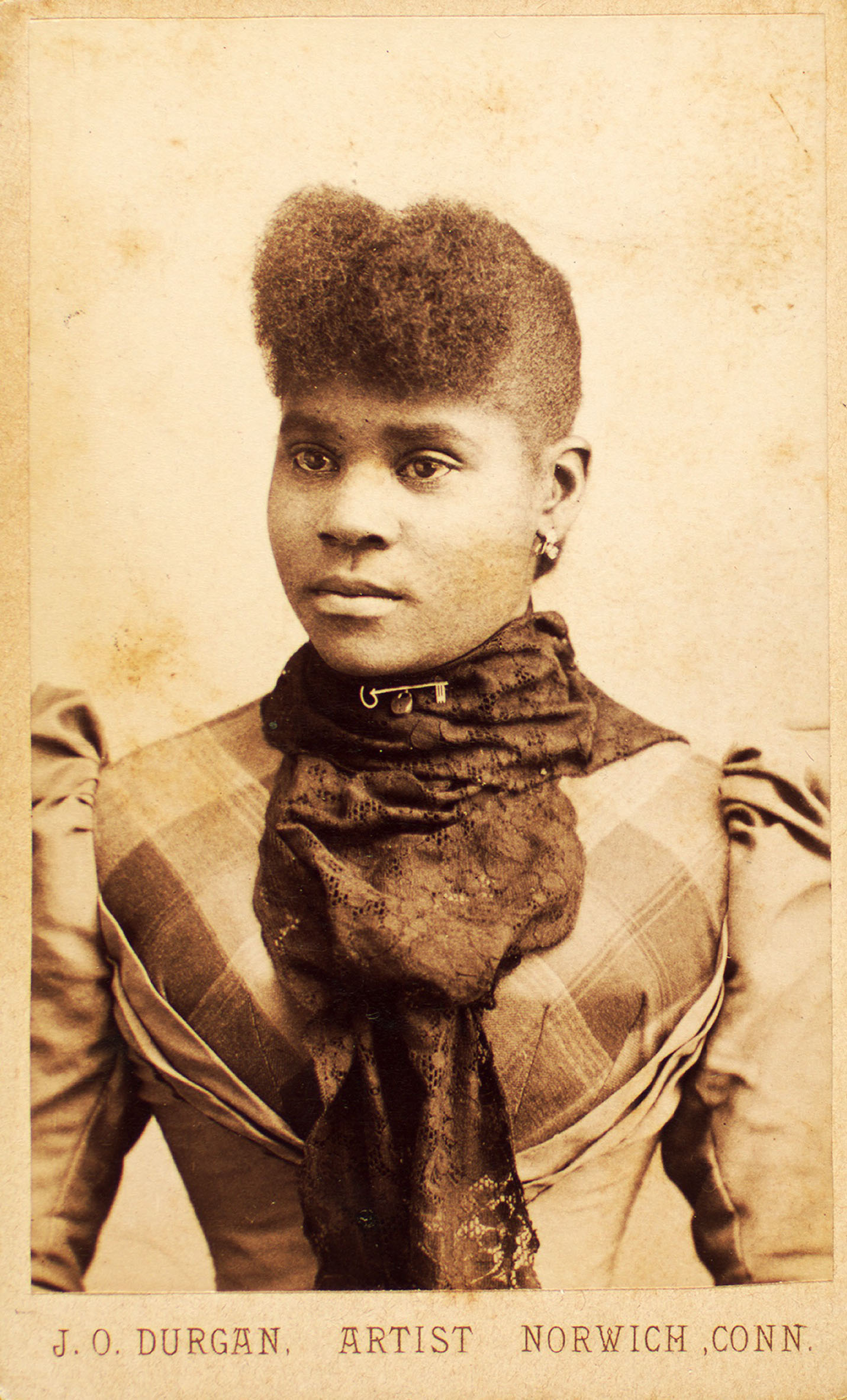

Half-Portrait of a Young Woman Wearing a Large Lace Scarf

In the years following the American Civil War, Black women and girls were particularly concerned with countering negative racial stereotypes that portrayed them as depraved prostitutes or asexual Mammies. To distance themselves from this demeaning imagery, they sought means of self-presentation that communicated their moral character, social status, and agency. Both dress and photography proved to be potent means for conveying these values. By adhering to Victorian standards of dress and femininity, characterized by style, cleanliness, and modesty, African American girls and women could demonstrate their inclusion within the respectable middle-class. Through the display and exchange of photographic portraits, they became both producers and consumers of this new medium, crafting stories and images of themselves and their families that better represented their communities. The photograph presented here, taken in the late 1880s by the firm J. O. Durgan of Norwich, Connecticut, is evidence of these values. Although the young woman's identity is unknown, her tasteful appearance distinguishes her as a member of the flourishing Black middle class that emerged in New England cities in the second half of the nineteenth century. Following the fashionable dress of the day, she wears an immaculately tailored plaid bodice with a narrow waist and puffed shoulders. Her hair is carefully arranged in a chignon that shows off her modest drop earrings, while a large, machine-made lace scarf is tied around her neck and adorned with a lace pin in the shape of a key.

According to cultural historian Deborah Willis, lace scarves, brooches, and drop earrings feature prominently in the portraits of Black women at the turn of the century. These accessories were intended to recast the Black woman as "a collector of fine clothing, preserver of ancestral mementoes and enthusiastic participant in creating the image of the 'New Woman.'" Probably carefully chosen for this photographic portrait, the sitter's lace scarf and highly tailored dress bodice contribute to her construction of a dignified identity by communicating quality and social position. In this way, clothing—and lace especially—was an important tool for challenging stereotypes, negotiating citizenship, and expressing one's sense of self-worth.

Martha Pickman Rogers in Her Wedding Gown

The development of photography offered the opportunity to capture and preserve memories of important events such as weddings. This daguerreotype, produced by the Boston-based photography firm Southworth & Hawes, shows Martha Pickman Rogers (1829–1905) on her wedding day, June 1, 1850. The daughter of John Wittingham Rogers and Anstiss Derby Pickman, Martha came from prominent Boston and Salem merchant families. At the age of twenty, she married John Amory Codman (1824–1886), a landscape painter who made his wealth from his family’s real estate business. During their marriage, Martha and John had two children, John Amory Codman Jr. and Martha Catherine Codman.

On her wedding day, Martha wore a white silk moiré gown. Following the fashionable silhouette of the day, the bodice fits closely over her torso and features a modest, off-the-shoulder neckline trimmed with a lace bertha collar. The fullness of her skirt, pleated at the waist and supported by multiple petticoats, accentuates her narrow waist. Martha’s accessories include short white gloves, a pearl necklace, a corsage of orange blossoms, and a long tulle veil. Perhaps inspired by the royal wedding that took place when Martha was a girl, her dress shows a striking resemblance to the white silk satin gown heavily trimmed with Honiton lace worn by Queen Victoria on the occasion of her marriage to Prince Albert on February 10, 1840. The Queen’s wedding was highly publicized and details of her appearance were disseminated in Britain and abroad through newspaper reports, prints, and souvenirs.

In a departure from the red ermine state robes worn by previous monarchs, Victoria’s radiant gown in white Spitalfields silk satin followed contemporary fashionable taste and communicated her desire to be seen as a wife, not a monarch, on her wedding day. Embellished with a rich flounce, bertha collar, and veil of Honiton lace, Victoria’s ensemble also demonstrated support for the flagging handmade lace industry in Devon, which had been in decline since the market embraced machine-made net. While the white wedding gown and alluring blonde lace veil had long been popular choices for aristocratic brides, Victoria’s decision to wear white on her wedding day reinforced its associations with love and purity and made such a gown desirable at all levels of society.

Still, in 1850, the high cost of textiles and labor meant that most brides could not afford a dress specially made for the occasion and they instead opted for smart day dresses that could be worn more than once. Thus, Martha Pickman Rogers’ white wedding gown, with its fine lace collar emulating the Queen’s, reflects her status as a woman of wealth as much as it connotes romance, innocence, and fashionable taste.

Woman with Black Lace Shawl and Stereoscope

The unidentified young woman in this portrait wears a black lace shawl draped around her skirt. She sits by a tabletop stereoscope, a new technology which appeared in the 1850s following the advent of photography. A stereoscope enabled its owner to view photographic slides at home. This portrait was mailed with an inscription on the back that reads, “Your Own Chicken,” perhaps referring to a pet name between intimates. The young woman was photographed in Janesville, Wisconsin around the end of the Civil War. Assuming she lived in this remote location, her shawl was probably machine-made. At the time, Chantilly lace shawls imitating handmade lace were made by machine in both England and France. The two examples illustrated here are from a lace-making center in Nottingham. High-quality machine-made lace was difficult to distinguish from its handmade counterpart and therefore conveyed the same elegance and fashionability that was previously reserved for the elite. With her lace and the stereoscope, this young woman demonstrates her access to newly available technologies and luxuries for the American middle classes.

Josephine A. Silone Yates

Educator and activist Josephine A. Silone Yates posed for this photograph in Washington D.C. around 1885. Her dress features lace trim that peeks out from pleated sleeve cuffs and the points of a fine net collar are visible around her neck. Over her bodice she wears a dark lace kerchief, probably secured with a pin. At the time, Yates was heading the Department of Natural Sciences and teaching chemistry at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. She was the first Black woman to hold a full professorship and the first woman to head a university department in America. She was born in Mattituck on Long Island, and perhaps traveled to Washington on one of her trips to the East coast to visit family. Also of note is that Yates’ older sister, Harriet Silone, was a talented dressmaker who worked in Newport, Rhode Island.

In addition to the success she achieved in her career, Yates was an activist for Black women’s rights and was a correspondent for several publications, including The Women's Era. This periodical was tied to the African American women's club movement that provided women of color with access to education, skills, and hobbies as well as tools for political activism. Although it is unlikely that Josephine wrote for The Women's Era fashion column, the above excerpt illuminates how women could utilize affordable, machine-made lace to spruce up simple wardrobes: "The possession of numerous bits of lace in the line of jabots, collarettes and fichus is the greatest aid a woman with a scanty wardrobe can have… The little collarettes of muslin and narrow lace which lie over stock collars in tabs or points are dainty affairs." Although Yates probably did not have a “scanty” wardrobe due to her position, her dress would still have been judged by the same feminine aesthetic criteria described by The Women's Era.

Edward Henry Little

The photograph of Edward Henry Little (1879–1919), taken in Newburyport, Massachusetts, tells a remarkable story of lineage, tradition, and local industry. The young Edward appears seated, wearing a striped silk dress with lace collar and cuffs. During the nineteenth century, it was quite common for young boys to wear dresses until the age of four or five, when they were given their first pair of trousers. While the photograph dates to the 1880s, the dress, which is now preserved in the Historical Society of Old Newbury, was made almost a century earlier between 1795 and 1798. The dress was originally won by Eleazer Johnson III (1790–1890), Edward’s great-grandfather. According to family accounts, wearing this dress became a tradition for the young males in the Johnson family. When Eleazer Johnson III married Fanny Toppan (1791–1870), the dress was passed down to their first born son, Eleazer Johnson IV (1813–1881), who later shared the dress with his son, Chas Johnson (1858–1932). Although Chas did not have children, he chose to continue the tradition, sharing the dress with his sole cousin's son Edward. In the photograph, Edward's dress communicates his strong family ties, placing him in a long line of Johnson men.

The lace trim on Edward Little’s dress features the Torchon-type ground and simple, free form motifs characteristic of Ipswich lace.

Just as fascinating as this garment's unique family history is what the lace trim reveals about the family's Massachusetts roots, their social standing, and even their political leanings. The lace that embellishes this dress is a product of the Ipswich, Massachusetts lace industry, the only handmade lace making center in America to achieve commercial success. Ipswich lace emerged during the second half of the eighteenth century in response to mounting frustration caused by English taxation. As taxes on luxury goods including lace, tea, and sugar surged, colonists increasingly felt the need to reject foreign goods. In Ipswich, needleworkers capitalized on anti-British sentiment and the growing demand for domestic goods, producing handmade bobbin lace that was far less expensive than costly imported lace. While the most affluent citizens continued to purchase fine imported laces from the illustrious lace centers in England and Europe, moderately priced Ipswich lace found an enthusiastic market amongst middle-class consumers, for whom lace consumption had previously been inaccessible.

That the dress made for Eleazer Johnson III features Ipswich lace, rather than imported lace, is therefore interesting, given the prominent socioeconomic status of its wearer. Eleazer Johnson's father, William Pierce Johnson was a shipmaster and owner of a large number of vessels engaged in the West India trade. In 1800, he was ranked the third wealthiest man in Newburyport. The family certainly could have afforded higher-quality, imported lace, so why opt for the less prestigious, locally-made lace? One might speculate that in the years following the American Revolution, the purchase of Ipswich lace was motivated by patriotism. If this was the case, then by dressing their son in Ipswich lace, the Johnsons not only made an investment in the newly-formed nation's economy, but also demonstrated their commitment to early American ideals of liberty, capitalism, and democracy.

Mary Ann Donaldson

Right: Portrait of Nancy Maria Donaldson Johnson, 1875. Albumen photograph, carte de visite format. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., LC-DIG-ppmsca-54216.

Sisters Mary Ann Donaldson (1798–1881) and Nancy Maria Donaldson Johnson (1794–1890), aged 77 and 81 respectively, are pictured here wearing different styles of lace lappets (decorative bands attached to a cap). Lappets have been worn in religious contexts since medieval times. As popular elements of women’s headdresses, they were most fashionable from the 1680s to the 1770s, although they came back into vogue in the early and mid-decades of the nineteenth-century. The hairstyles and caps of the two sisters are about 25 years out of date, reflecting the preference for earlier styles that were often maintained by older women and men. Each sister here wears a different type of lace, conveying their individuality and taste.

Both sisters were active in the American Missionary Association and from 1862-1865 taught previously enslaved people at Port Royal, South Carolina. The "Port Royal Experiment" (1862-1865) was the first major attempt by Northerners to reconstruct the Southern political and economic system. The Union Army’s occupation of South Carolina resulted in the emancipation of approximately 10,000 enslaved men, women, and children. These workers were paid $1 for every 400 pounds of harvested cotton. The Port Royal Experiment created schools and hospitals in hopes that former enslaved people would eventually be able to buy and run plantations. Mary Ann Donaldson and Nancy Johnson were among 53 missionaries-including skilled teachers, ministers, and doctors-who volunteered to promote this experiment.

With the death of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, interest and momentum of the experiment waned. Andrew Johnson worked to restore white ownership of the lands newly acquired by former slaves.

In addition to her teaching and missionary work, Nancy was an inventor. She patented the first hand-crank mechanism for ice cream freezers in 1843. Mary, who never married, lived most of her life with Nancy’s husband and two children in Washington, D.C.

Sallie

Sallie is identified only by her first name on the back of this carte de visite. This young African American woman is dressed in a light-colored day dress with contrasting black lace that was likely machine-made. The silhouette of Sallie’s dress is characteristic of early to mid-1860s fashion in the United States: the close-fitting bodice has a slightly raised waistline, the gored skirt is smooth through the hips, and the full-cut, curved sleeves that taper at the wrist and are set in below the natural shoulder line. Cuffs were often accented, either with a contrasting fabric or as seen here, with lace. A band of scallop-edged lace also decorates Sallie's bodice and upper sleeves, much like the lace berthas on evening wear at this time. A very similar American dress in green silk taffeta is in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. The high neckline of Sallie's dress is accentuated with a white lace collar and she wears delicate jewelry and a ringlet hairpiece over her natural hair. Based on her ability to dress fashionably in the 1860s and the fact that she had her photograph taken, Sallie may have been a free Black woman living in the Northeast.

Roxana Wentworth

Roxana Atwater Wentworth (1854–1935), daughter of Chicago mayor and prominent Illinois politician John Wentworth (1815–1888), married Clarence Winthrop Bowen (1852–1935) in January 1892. Wentworth chose a popular silhouette for her wedding dress: a tightly corseted waist dramatizes the fullness of the bust and hip. While only small amounts of point de gaze needle lace lace decorate the bust and the bouquet, adding interest to the plain white dress, it is the elaborate cap and veil in matching point de gaze that advertises Wentworth’s wealth and taste. Wenthworth’s 83-inch cathedral-length veil formed a train behind her as she walked, covering the hem of her dress and the aisle with hundreds of small floral garlands. Wentworth most likely met with the makers of the veil at least a year before her wedding to design this complex piece of lace.

Point de gaze is a Belgian needle lace that appeared in the early eighteenth century and continued to be produced until the middle of the twentieth century. The use of a gauze ground gave the decoration a light, floaty quality ideal for veils, parasols, and bridal accessories. Despite the introduction of machine-made lace in the nineteenth century, handmade point de gaze remained a popular accessory for upper class women in both the United States and Europe, although a large, high-quality piece might take a year to create.

Wentworth’s veil, cap, and trimmings likely cost a great deal of money and were most likely paid for by either her father or fiance. However, the ensemble was evidently regarded as an heirloom by Wentworth, and her daughter, Roxana Wentworth Bowen (1854–1935), would eventually wear the same veil and cap to her own wedding in 1917.

This interactive is best viewed on a large screen.