Kate is a woman living with her two small children in a parish workhouse in Bedfordshire, England in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. At this time, Bedfordshire and other rural English counties in the Midlands were home to increasing numbers of underemployed men and women; for women, making lace in a workhouse provided a way to earn wages and afford rent. In this part of England, women primarily made bobbin lace, and often brought their own equipment into the workhouses. Their work would be sold anonymously by overseers at these lacemaking enterprises. Many young girls received instruction on lacemaking in workhouses, where, before the establishment of child labor laws in the late eighteenth and early decades of the nineteenth century, much of the lace was produced by children.

Click on the tabs to learn more about Kate’s life as a lacemaker.

Family Life

Kate is one of several siblings born into a community engaged in the stocking industry in Nottingham, which is located in England’s Midlands region. Here children helped their mothers produce hosiery, gloves, and other garments on a stocking frame, which was first developed in 1589 by William Lee in Calverton, near Nottingham. Kate grew up in this commercial environment, and also learned to make lace at the age of six. When they did not have any work to do, Kate and her siblings liked to play games in the street with the other children.

“The Art of Stocking-Frame-Work-Knitting,” The Universal Magazine, v. 7, p. 50, 1750. Engraving. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, This image is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.

Click Image to Enlarge

Carington Bowles, The Lace Wearer, Rewarding the Lace Maker, 1783. Hand-colored mezzotint. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1935,0522.1.60.

At age eighteen, Kate met her husband, John, who was employed at a printed cotton manufactory mill in Bedfordshire. She moved to Bedfordshire with him and continued to make lace to support her new family. When John became ill and died three years later, Kate contemplated her options. She could not go home because her ailing mother was barely able to feed her younger siblings. When Kate could no longer afford rent, like many other women in Bedfordshire, she moved into a parish workhouse under the agreement that all lace she made would be sold by an overseer.

Lace Education

Kate learned to make bobbin lace as a child in Nottingham, which, like Bedfordshire, was another prominent center for lace manufacturing. She was taught by her mother with help from other lacemaking women, as it was something that could easily be done in one’s spare time with relatively simple tools.

Other girls she knows acquired lacemaking skills while growing up in workhouses that frequently employed mistresses to teach female children how to make this luxury textile. Surrounded by lacemakers, the workhouse was the perfect environment to learn this trade—one which provided these girls and women with the means to support themselves once they left. As Kate became older, she often gave instruction to other girls living in the workhouse.

Sameul Okey after Giacomo Francesco Cipper, ca. 1760s. Mezzotint on paper. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 2010, 7081.2657.

The lacemaker, 1770-1800. Mezzotint with some etching. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 2010,7081.1214.

Local Industry

William Finden after Richard Westall, A woman seated on a chair outside a cottage, making bobbin lace, a little boy seated beside her on the left, reading a book; title-page to ‘Truth’ from ‘The Minor Poems of William Cowper of the Inner Temple’ in John Sharpe’s ‘British Classics’; after Westall, 1817. Etching and engraving. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1867,0713.467.

Many towns and areas of the Midlands—including Nottingham and Bedfordshire—boasted thriving lace industries in the late eighteenth century. Many women in the region relied upon the lace market to earn a living, either by working independently from their homes or in small workhouses or by selling the tools and materials required to make lace. Without this means to earn a living, these women may have faced starvation; without money for rent, a crowded workhouse with poor living and working conditions was the only option available to Kate. By the 1780s, machine-made lace became more common, and many factories opened in the area in the following decades.

Although the working conditions in workhouses stayed largely the same, the wages a lacemaker could earn increased during Kate’s lifetime.

Learn how this compares to the lacemaking industry in 17th century Venice by clicking here.

William Finden after Richard Westall, A woman seated on a chair outside a cottage, making bobbin lace, a little boy seated beside her on the left, reading a book; title-page to ‘Truth’ from ‘The Minor Poems of William Cowper of the Inner Temple’ in John Sharpe’s ‘British Classics’; after Westall, 1817. Etching and engraving. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1867,0713.467.

Techniques, Tools, and Materials

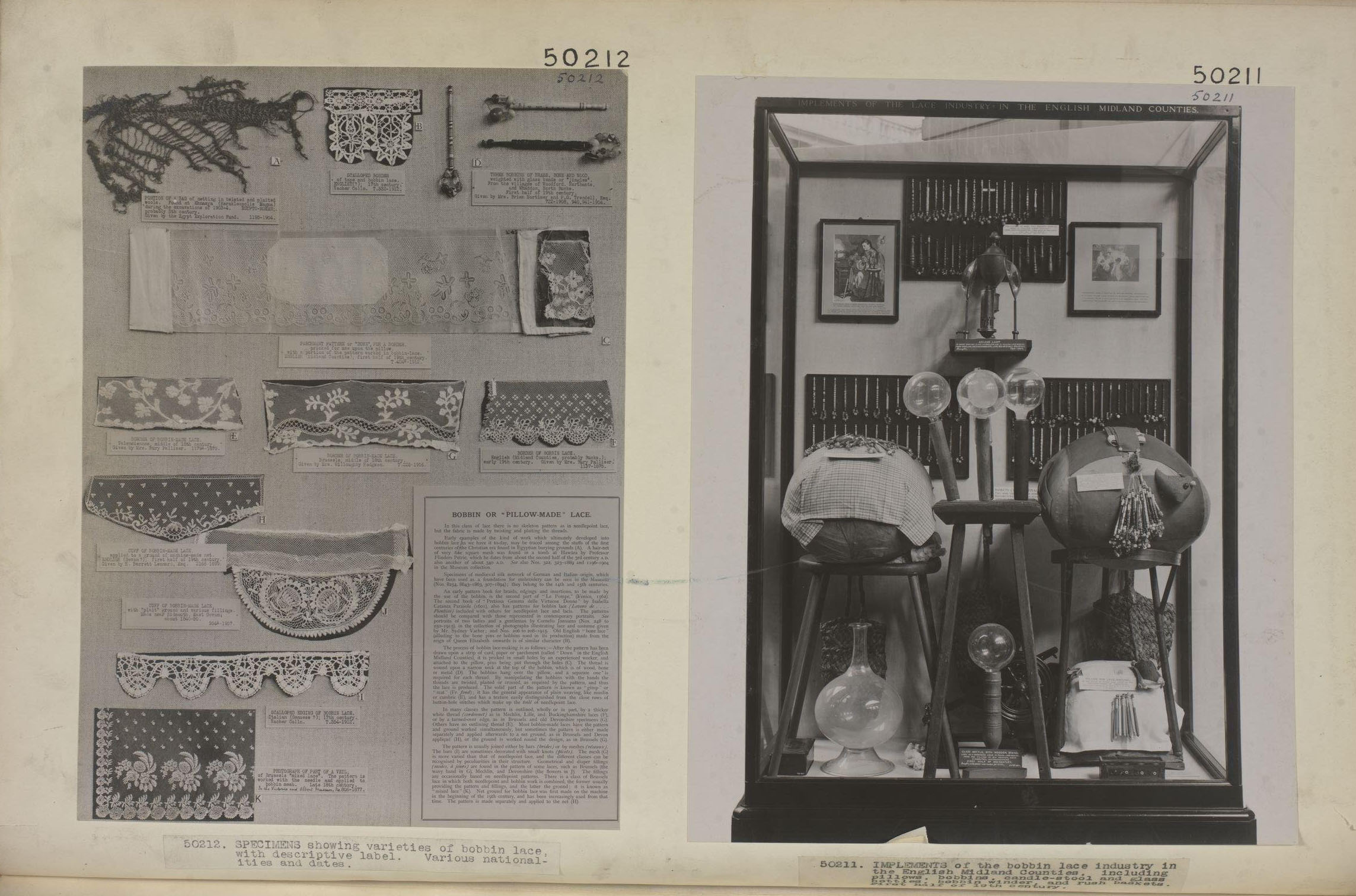

Archival photograph of a display at the Victoria and Albert Museum on bobbin-lace making in the Midlands featuring a pillow lace maker’s ‘candle stool’, British, about 1800-1850. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 855-1907.

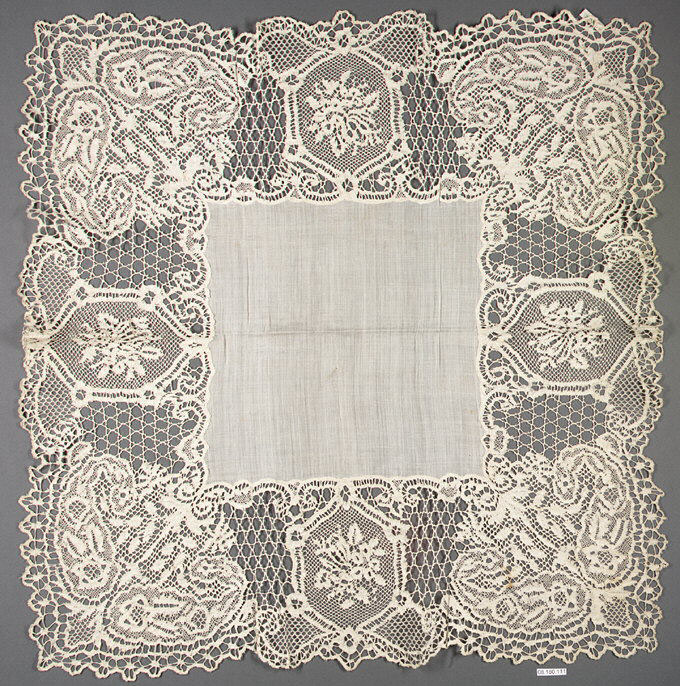

To make her lace, Kate uses a bolster pillow wrapped in cloth, wooden bobbins, steel pins, white linen thread, and a parchment pattern. Kate purchases the other necessary items from a local shop that sells lacemaking materials. Patterns were chosen and provided by her overseer, who kept abreast of which styles and motifs would sell. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Bedfordshire lacemakers made several different types of bobbin lace that were chiefly influenced by French lace.

To make her lace, Kate uses a bolster pillow wrapped in cloth, wooden bobbins, steel pins, white linen thread, and a parchment pattern. Kate purchases the other necessary items from a local shop that sells lacemaking materials. Patterns were chosen and provided by her overseer, who kept abreast of which styles and motifs would sell. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Bedfordshire lacemakers made several different types of bobbin lace that were chiefly influenced by French lace.

Daily Life

A girl seated to front on a rock in front of a cottage, with head tilted to left, making bobbin lace; proof before letters, ca. 1770-1830. Stipple. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1867,0309.1231.

On weekdays, Kate rises early to wash and dress her children. She feeds her baby, prepares a small breakfast for herself and her eldest child, and at eight o’clock begins her workday. Sometimes Kate works in the designated lacemaking room, but in the warmer months, she will take her work outside so that her son can play while she keeps watch. There, passersby or charitable patrons may stop to talk with her, either about commissions or to give her a shilling or two. Kate keeps at her lacemaking until five o’clock, when she stops for supper and to put her baby to sleep. Lacemaking occupies her well into the evening, when she may finally go to sleep herself. At the end of the week, she’ll receive her wages, which are calculated according to how much the overseers received for her lace that week. She hopes she will earn enough to feed and clothe her children.

A girl seated to front on a rock in front of a cottage, with head tilted to left, making bobbin lace; proof before letters, ca. 1770-1830. Stipple. © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1867,0309.1231.

On weekdays, Kate rises early to wash and dress her children. She feeds her baby, prepares a small breakfast for herself and her eldest child, and at eight o’clock begins her workday. Sometimes Kate works in the designated lacemaking room, but in the warmer months, she will take her work outside so that her son can play while she keeps watch. There, passersby or charitable patrons may stop to talk with her, either about commissions or to give her a shilling or two. Kate keeps at her lacemaking until five o’clock, when she stops for supper and to put her baby to sleep. Lacemaking occupies her well into the evening, when she may finally go to sleep herself. At the end of the week, she’ll receive her wages, which are calculated according to how much the overseers received for her lace that week. She hopes she will earn enough to feed and clothe her children.

Culture and Community

Kate is part of a community of lacemakers living in the workhouse. To quicken the pace of their work, they sing as they twist their bobbins, and their songs are often of lace and lacemakers like themselves. Despite these small joys, Kate’s daily toil feels endless; it may take up most of her waking hours for the rest of her life, and subsume her daughter’s life too.

Peter Kempson, Leighton Buzzard halfpenny issued by Chambers, Langston, Hall & Co.1794. Copper. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, 1977-381/1. This image is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License.

Although their wages could be meager, particularly in the workhouses, lace’s important role in the local economy was acknowledged, and lacemakers were respected within their communities. However, lacemakers were persistently stigmatized as simpleminded or immodest. A common trope about lacemakers was that they had fallen from grace and were being punished for their situation. Many of the songs about lacemakers from the eighteenth and nineteenth -centuries recount the hardships lacemakers endured and also reveal the effects of such moralizing assumptions on these female artisans.

Anne Sanders Wilson, Paper doll, 1832. Watercolor painted on card. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, T.361:16-1998.

These paper dolls were created to accompany the manuscript, “The History of Miss Wildfire,” which follows the story of a “fashion-stricken” young woman who is forced to become a lacemaker after the death of her father leaves her destitute.

Learn about Geneviève’s similar lacemaking community in eighteenth-century Valenciennes here.