Geneviève is a young lacemaker from the Valenciennes region of France. Born in the mid-eighteenth century into an impoverished family, she was sent at the age of seven to a charitable religious institution to learn how to make bobbin lace. Under constant supervision in a highly regulated environment, Geneviève learned lacemaking techniques alongside other girls, eventually becoming proficient enough to gain a place at a lace workhouse. Here, she makes a modest, although unreliable, income working long hours under harsh conditions.

Lacemaking, one of the few trades available to women in the eighteenth century, enables Geneviève to avoid abject poverty. Her hard-won skill also widens the range of options available to her. With the measure of financial independence lacemaking offers, Geneviève can choose whether to marry and perhaps have children, or to ascend to the ranks of her industry as a teacher. Either way, her early education at the lace school has improved her life.

Click on the tabs to learn more about Geneviève’s life.

Family Life

Poverty touched every aspect of Geneviève’s childhood. Her mother worked as a spinner and her father as a laborer—both lines of work that were often dependent on the needs of local markets and did not offer a stable income. Geneviève and her many siblings lived in a simple cottage with just a few pieces of furniture and little of anything else. They ate bread purchased at the market or soups that Geneviève’s mother made as she worked at her spinning. With many mouths to feed, Geneviève’s family elected to send her to a charitable religious institution to learn lacemaking. This may have been one of the best options for Geneviève’s family and for Geneviève herself, who would learn a marketable trade.

Lace Education

Geneviève learned lacemaking at a charitable religious institution in Valenciennes. Her parents sent her to the school at age seven because they could not afford to raise a large family. In the extremely strict environment of the school, Geneviève learned the complex techniques required to make Valenciennes bobbin lace, how to read and write, and also received religious education. Girls followed rigid daily schedules of instruction and were not permitted to leave, even to visit their families. Once, Geneviève tried to run away, but she was caught, imprisoned for 15 days, and whipped in front of the other girls at the school. By the end of her time at the school, Geneviève was very proficient at making Valenciennes lace, and, when she was fifteen years old, she transitioned into an affiliated workhouse where she resides now. Here, she will continue her lacemaking education as an apprentice to more senior lacemakers. One possibility for Geneviève’s future is to become a mistress, and instruct young women like herself.

Learn about the similarities to lacemaking education in Venice in the seventeenth century by clicking here.

Joannes de Maré, Orphans in the Maidens’ House, 1676. Oil on canvas. MAAGDENHUIS/Stad Antwerp, A178. Photo: Pat Verbruggen.

Local Industry

In the eighteenth century, Valenciennes was known throughout Europe for its high quality lace that depended, in part, on the fineness of the locally grown and processed linen thread. Established in the seventeenth century, the industry experienced a decline in the early eighteenth century, but then flourished again during the final decades of Louis XV’s reign (1715–74). From the 1740s through the 1760s, demand from the French aristocracy and the wealthy upper classes for Valenciennes lace was high, and numerous lacemakers like Geneviève were employed to produce a constant supply of trimmings and accessories for this discerning clientele. The Tribout family of lace merchants presided over this boom. They commissioned work from individual lacemakers, families of lacemakers, and charitable institutions; they distributed patterns created by local artists or those from beyond Valenciennes to workshops; and they sold the finished lace to Parisian lace purveyors or to clients directly.

The successful business activities of François-Joseph and Anne Cécile Tribout, and later their daughter Claire, supported the training of girls like Geneviève and their subsequent employment in a workhouse. In the 1740s, Geneviève made 250 livres each year—a better income than her mother could earn as a spinner. But despite the fact that the Valenciennes lace industry grew over the next three decades, wages remained stagnant, and by 1770 lacemakers like Geneviève were barely able to support themselves and their families. After its peak in the 1770s, the lace industry in France—including Valenciennes—went into a decline and did not revive. Lacemakers’ wages and jobs decreased in tandem with this downturn.

The successful business activities of François-Joseph and Anne Cécile Tribout, and later their daughter Claire, supported the training of girls like Geneviève and their subsequent employment in a workhouse. In the 1740s, Geneviève made 250 livres each year—a better income than her mother could earn as a spinner. But despite the fact that the Valenciennes lace industry grew over the next three decades, wages remained stagnant, and by 1770 lacemakers like Geneviève were barely able to support themselves and their families. After its peak in the 1770s, the lace industry in France—including Valenciennes—went into a decline and did not revive. Lacemakers’ wages and jobs decreased in tandem with this downturn.

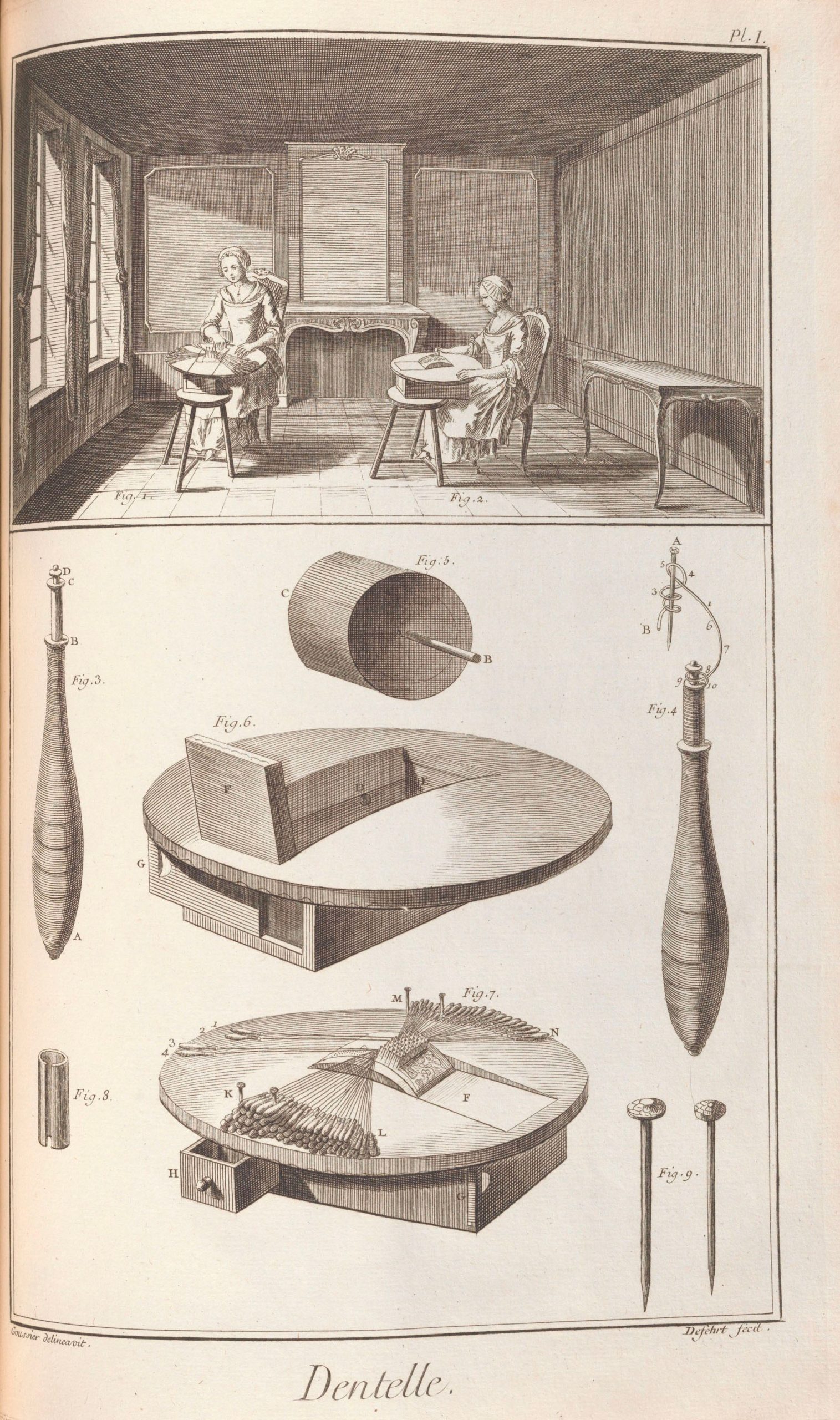

Techniques, Tools, and Materials

To create Valenciennes lace, Geneviève needs a pattern, pillow, bobbins, pins, and thread. These few tools allow her to make everything from the simple designs she learned as a young girl to the highly complex laces she executed as she became more technically proficient. While in school, Geneviève was provided with thread that the religious institution purchased from the Tribout family lace merchants. Now she has transitioned to the workhouse, Geneviève is responsible for buying her own thread from the Tribouts or other thread manufacturers. This is a substantial financial risk, but Geneviève has no option but to accept it.

Valenciennes bobbin lace differs from other types in that the diamond-shaped net ground is created at the same time as the pattern. It is also distinctive for not having an outlining thread around the decorative motifs. These characteristics mean it would have been slightly simpler and faster for Geneviève to produce than other types of lace popular in the mid-eighteenth century. However, it is still immensely labor-intensive work that requires Geneviève to bend over a lace pillow in concentration for twelve hours each day in poorly lit rooms. To create a light suitable to her task, she places a glass globe of water near a candle, which has the effect of magnifying the flame.

Pair of bobbin-lace lappets, Valenciennes, ca. 1730s. Linen. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, T.52&A-1949.

Two lacemakers, the first making lace and the second pricking a pattern on green vellum, “Dentelle et façon du point,” from Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, eds., Recueil de Planches, sur les Sciences, Les Arts Libéraux, et Les Arts Méchaniques, avec leur explication: Troisième Livraison, Briasson, Paris, 1765, vol. 3, plate 1. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933, 33.23(3).

“The Pillow-lace Maker” from a picture by James Lobley, The Graphic, March 11, 1871. Newspapers.com.

Elena Kanagy-Loux, Valenciennes lace in process, Bruges 2018. Courtesy of Elena Kanagy-Loux.

Daily Life

At the charitable religious institution where she learned lacemaking as a child, Geneviève had no personal liberty, and every part of her day was structured. She woke at five o’clock in the morning to participate in communal prayer; and when she was older attended mass. Next, Geneviève had an hour of reading and writing lessons followed by a quick breakfast. In the winter, Geneviève’s workday began at a quarter to eight in the morning and, in the summer, at a quarter to seven. She toiled at her lace pillow until noon and was then allowed lunch and a half hour of recreation time. After this brief break, Geneviève returned to making lace until half past seven in the evening in the winter and summer. At the end of this nearly fifteen-hour day, Geneviève had dinner, took part in evening prayers, and went to sleep, exhausted, in her dormitory. Geneviève rarely dared to disobey the directions of the mistresses or stray from the schedule. Punishments such as confinement or whippings were doled out to even the youngest girls, and she experienced them herself.

Joannes de Maré, Orphans in the Maidens’ House, 1676. Oil on canvas. MAAGDENHUIS/Stad Antwerp, A178. Photo: Pat Verbruggen.

Click Images to Enlarge

Geneviève’s daily life at the workhouse after leaving the school is almost as rigid. Under constant supervision by senior and assistant mistresses, Geneviève is expected to perform her work in the silent company of other lacemakers. If the senior mistress is pleased with the girls’ work, she might relax the rules a little, or even permit them to sing suitable songs.

Culture and Community

Geneviève expects to live nearly her whole life in the company of girls and women just like her who have come from poor families in the Valenciennes region. Even once she leaves the workhouse, the women with whom she works in close proximity will likely have come from the same school or from similar ones in the area. Despite the strict mistresses who control nearly every aspect of Geneviève’s life, she forms meaningful connections with the women toiling by her side. She sees young homesick girls enter the school and adjust to their new lives as she once did, and notices what happens to the older women who lose their eyesight and can no longer work. Perhaps she registers the injustice of the system that governs her life and attempts to change it. In fact, she was one of a larger group of lacemakers who wrote to the Tribout lace merchant family demanding unpaid wages and attempting to negotiate better prices for their work.

At around the age of 25, once she had saved enough money to afford to leave the workhouse, Geneviève will marry a carpenter and have children of her own. To facilitate the additional work of raising a family, she will take in piecework at home rather than make lace at the workhouse. Leaving this environment, despite its unyielding rigidity and harsh work conditions, will be bittersweet. Working alone, Geneviève will miss the company of the other women, especially the rare moments in which she and her friends were allowed to sing suitable songs or chat together. She wonders what her life would have been like if she had remained unmarried, and chosen instead to ascend the lacemaking ranks, perhaps one day to become a senior mistress herself.

Giacomo Ceruti, Women making Lace (The Sewing School), 1720-30. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Brescia, Italy. Sergio Anelli / Mondadori Portfolio / Art Resource, NY.

![Anna Beeck and Gaspar De Baillieu. “Plan de la ville et cittadelle de Valenciennes” from A collection of plans of fortifications and battles, 1684-1709 : [Europe], 1709. . Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C., G1793 .B4 1709.](https://exhibitions.bgc.bard.edu/threadsofpower/files/cache/2022/09/LA-1045-master-gmd-gmd5m-g5700m-g5700m-gct00127c-ca000021copy/2335949377.jpg)