UrbanGlass (New York Experimental Glass Workshop)

New York, NY

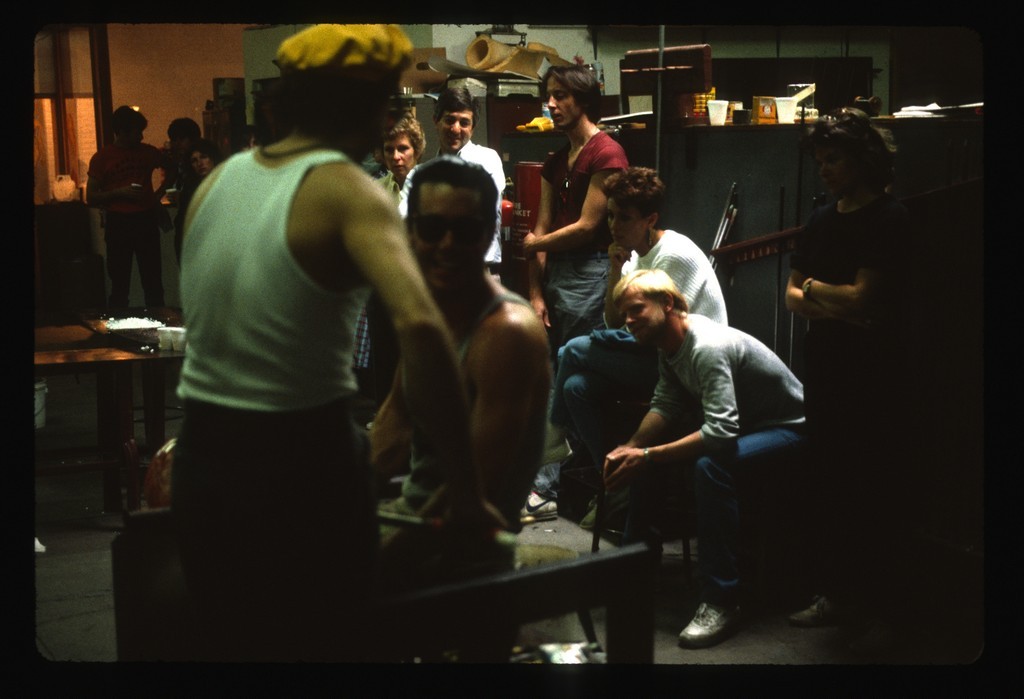

New York Experimental Glass Workshop, Mulberry Street location, New York, New York; left to right: Hans Frode, unidentified artist, Jane Bruce, Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir, Caroline Gangi, Terry Davidson, Barbara Stabin, Tina Yelle, James Horton, Fred Kahl. Copyright ©2017 Glass: The UrbanGlass Art Quarterly (www.glassquarterly.com). All rights reserved. This image originally appeared in the Summer 2017 edition of GLASS (#147). Permission to reprint, republish and/or distribute this material in whole or in part for any other purposes must be obtained from UrbanGlass (www.urbanglass.org).

“We thought of it as the laundromat approach. You don’t have a washing machine at home? You go to the laundromat [laughs.]—you use the washer-dryer and—and you’re good. And so it was that way with the equipment.”

Introduction

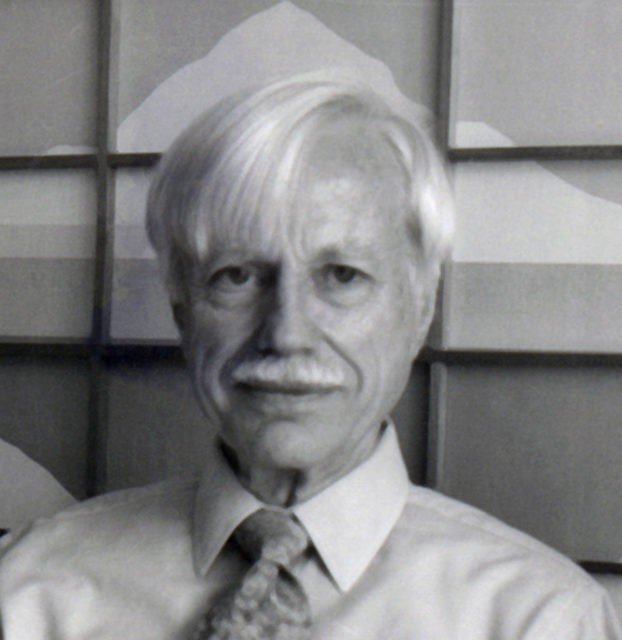

When the New York Experimental Glass Workshop (NYEGW), now UrbanGlass, opened its doors in Manhattan in 1978, it was the first public-access glass studio in the United States. Richard Yelle, frustrated by the lack of glassworking facilities in New York City, cofounded the Workshop as a communal space with fellow artists Joe Upham and Erik Erikson. Yelle had studied glass with Dale Chihuly at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and had built kilns with Upham at Massachusetts College of Art; Erikson taught stained glass at Parsons School of Design. Through NYEGW, they made glass furnaces and equipment available to any artist who wanted to rent studio time. The facility also became a center for glass education, offering formal and for-credit glassworking classes in addition to the shared expertise of an artistic community. NYEGW helped glass become an affordable medium for a wide range of artists, and its philosophy from the beginning was to include makers who don’t work exclusively in glass. Within just a few years, NYEGW was hosting Dale Chihuly, Toots Zynsky, and other innovators in the studio glass movement. As the studio’s size and range of activities grew steadily over the next three decades, it moved twice before settling in Brooklyn in 1991. In 1994, NYEGW changed its name to UrbanGlass.

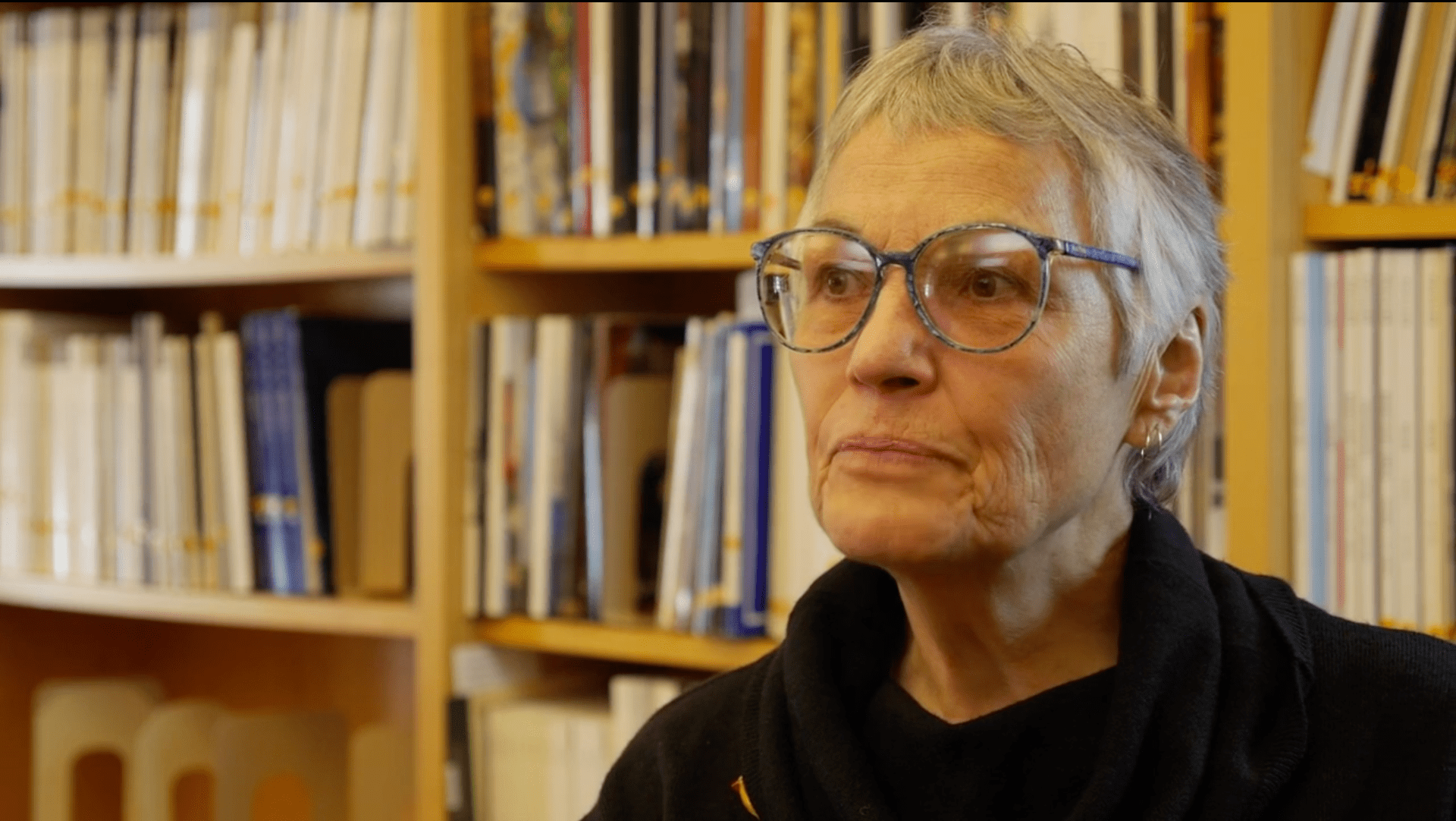

This section traces NYEGW’s growth and development from its first public space on Great Jones Street (1978–1981) to its second location on Mulberry Street (1981–1991), and on to its present home in Brooklyn. It highlights the role of the Workshop in bringing contemporary glass to wider audiences through its periodical, launched in 1979 as New Work and later renamed Glass, and through educational partnerships and public workshops. Paul Hollister attended and documented NYEGW workshops with Dale Chihuly in the 1980s and with Chihuly and Lino Tagliapietra in 1992. Also included here are excerpts from a 1982 conversation between William Morris and Paul Hollister; a Hollister recording made during a 1983 NYEGW workshop with Chihuly; videos documenting two Chihuly demonstrations from 1985 and 1992 created from Paul Hollister Slide Collection images; additional Hollister images; and several Hollister feature articles and reviews published by NYEGW. The section concludes with interviews conducted by Bard Graduate Center between 2018 and 2020 with Gary Beecham, Martin Blank, Jane Bruce, Sydney Cash, Karen Chambers, Paul DeSomma, William Gudenrath, James Harmon, Geoff Isles, Fred Kahl, Cybele Maylone, William Morris, Andrew Page, Lino Tagliapietra, Mary Shaffer, Richard Yelle, Tina Yelle, and Toots Zynsky.

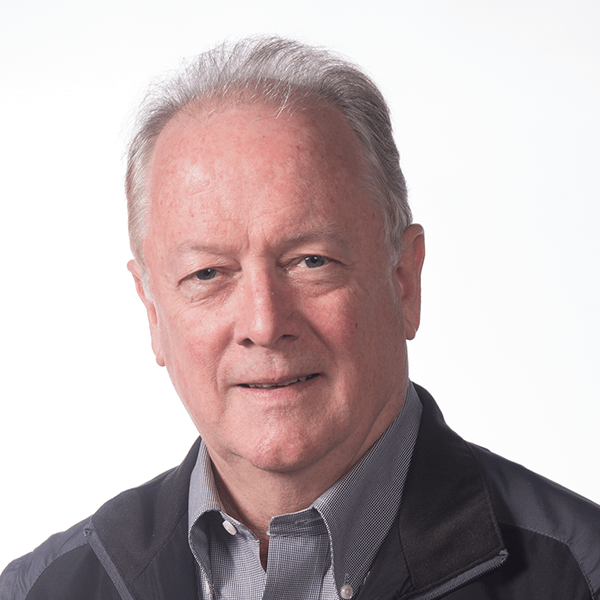

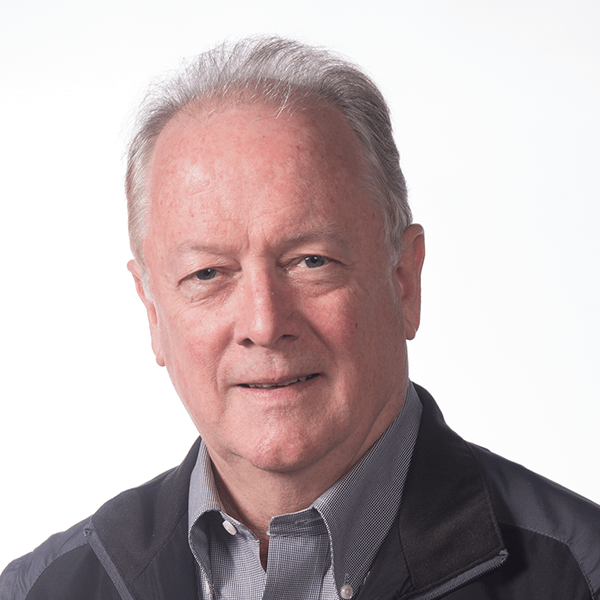

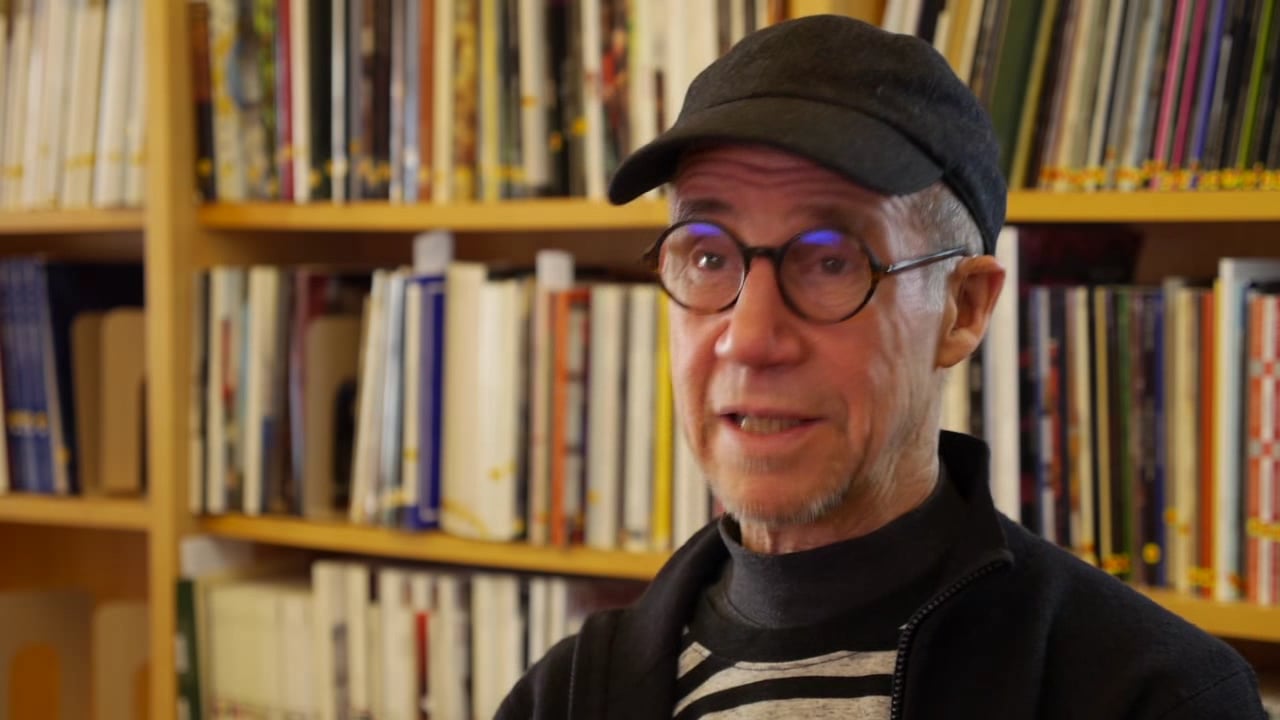

Andrew Page, Editor of Glass: The UrbanGlass Art Quarterly talks about Richard Yelle starting New York Experimental Glass Workshop rather than joining Dale Chihuly at Pilchuck.

00:55 Transcript

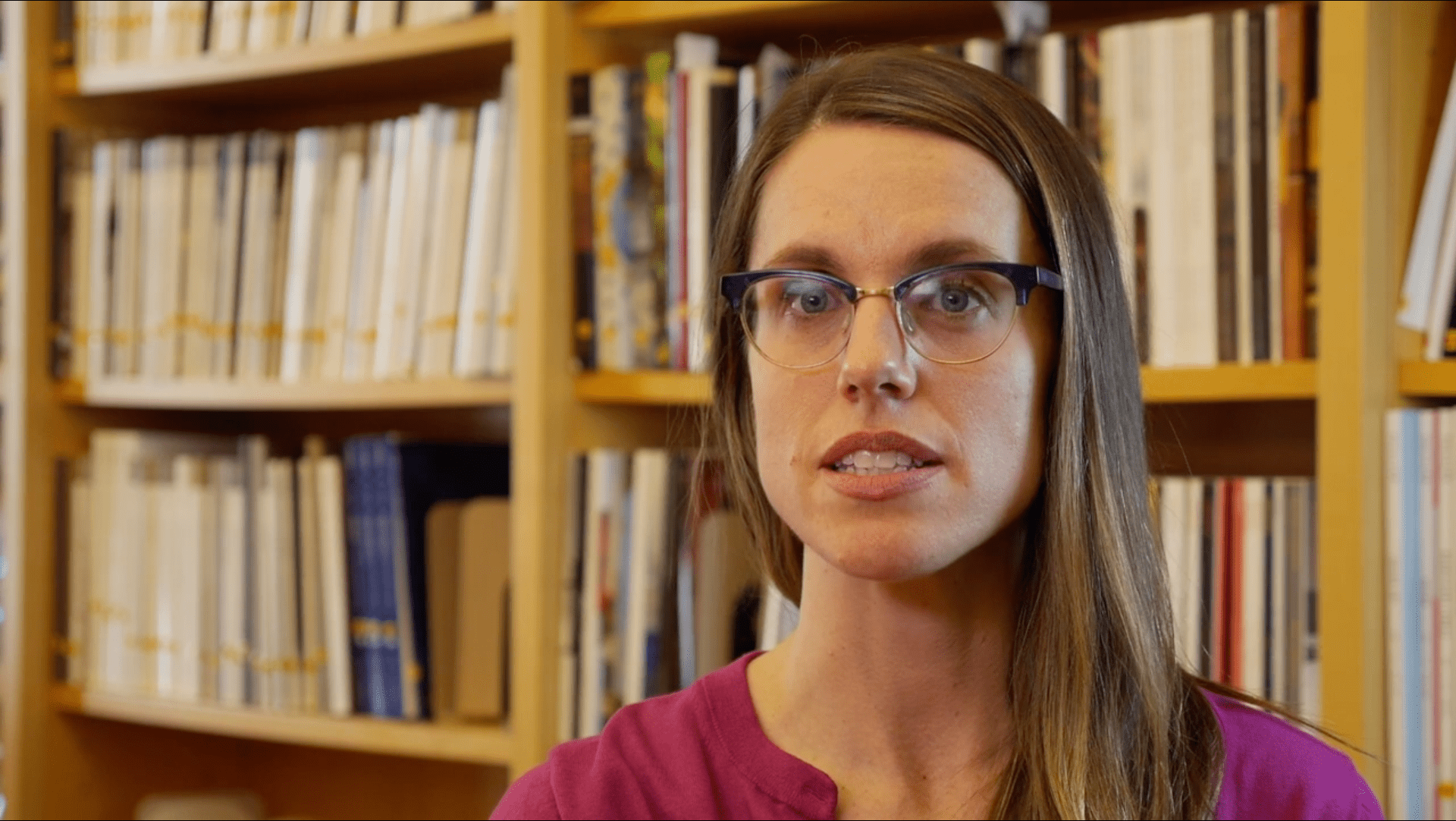

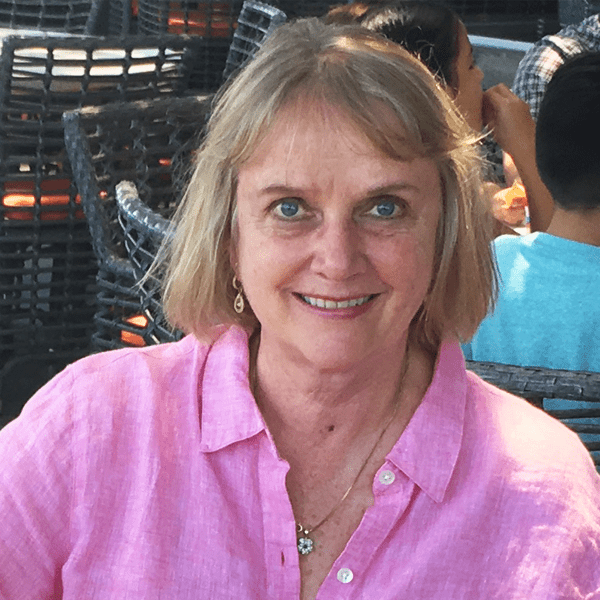

Former NYEGW Director Tina Yelle talks about why her brother, Richard Yelle, wanted to start a glass facility in New York.

01:05 Transcript

Early Years (1977–1981)

New York Experimental Glass Workshop began in 1977 in Richard Yelle’s loft at 54 Franklin Street, in SoHo. The following year NYEGW went public and moved into a basement facility at 4 Great Jones Street. The space was rented through Clayworks Studio Workshop, which occupied the first floor. The rental arrangement made sense for several reasons. Rose Slivka, then editor of Craft Horizons magazine, the first national craft magazine in the United States, and potter Susan Peterson had founded Clayworks specifically for artists who didn’t specialize in ceramics. NYEGW took a similar approach in welcoming glass novices. In addition, NYEGW’s glass furnace and annealer could share the gas lines Clayworks used for its kiln facilities.

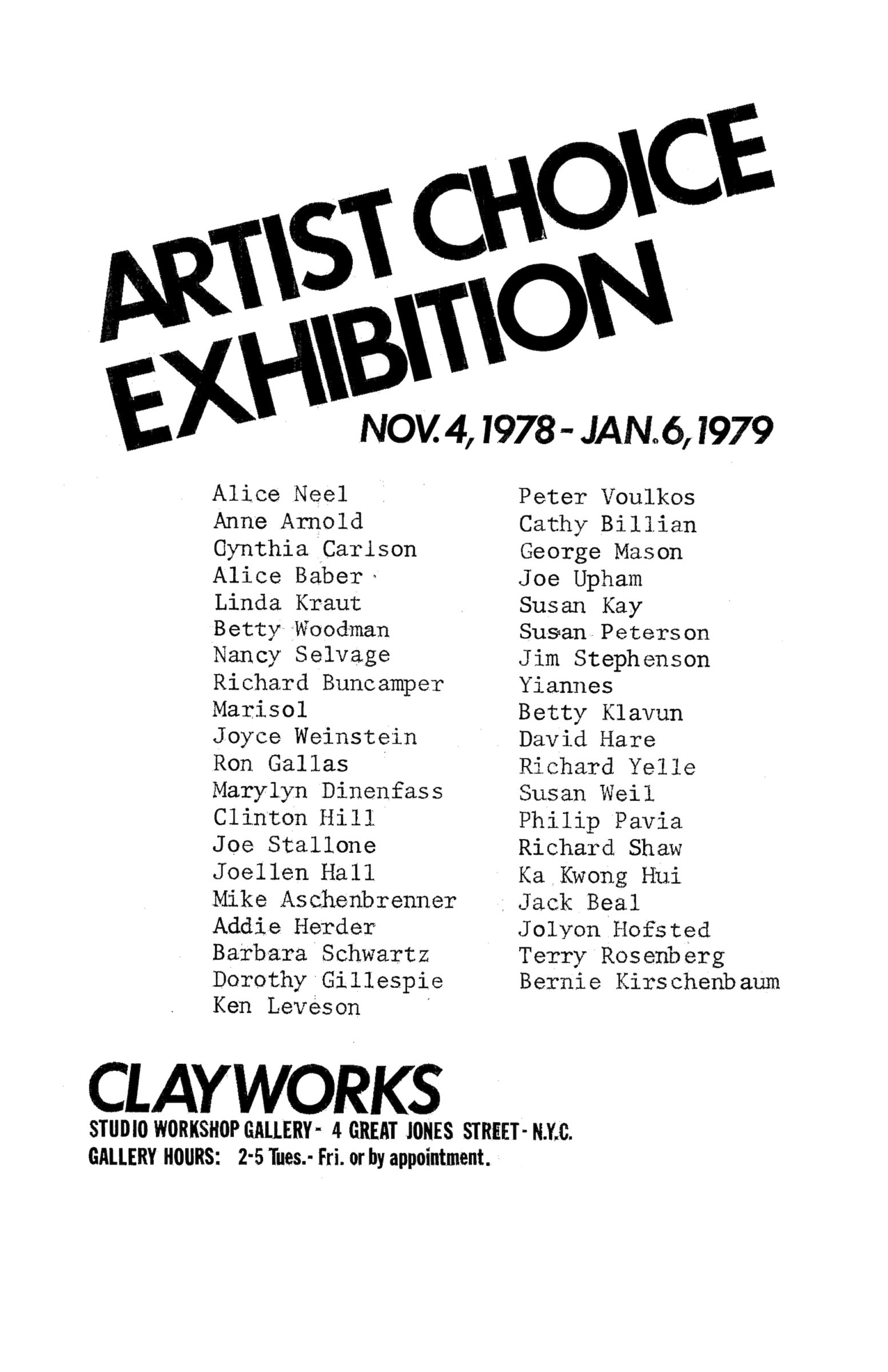

NYEGW and Clayworks enjoyed a close working relationship. Shortly after NYEGW moved in, Peterson asked Yelle to become director of Clayworks. Slivka and Yelle put on several joint exhibitions mixing studio craft makers working in clay and glass with artists from the contemporary art world, where Slivka had strong ties. Alice Neel, a frequent Clayworks visitor, and Willem de Kooning were among her friends. Glass artists such as Michael Aschenbrenner and Terry Rosenberg showed with artists like Neel, Marisol, and Hannah Wilke, and with ceramists Betty Woodman and Peter Voulkos. Glass artist Therman Statom and glass/light installation artist Ray King—who later designed NYEGW’s Mulberry Street gallery—also exhibited. Jun Kuneko, a clay artist and RISD graduate who lived at Great Jones Street with NYEGW cofounder Joe Upham, connected glass artist and fellow RISD graduate Toots Zynsky to the Workshop. In 1980, Upham hired Zynsky as executive director of NYEGW, and she began writing grant proposals for the organization.

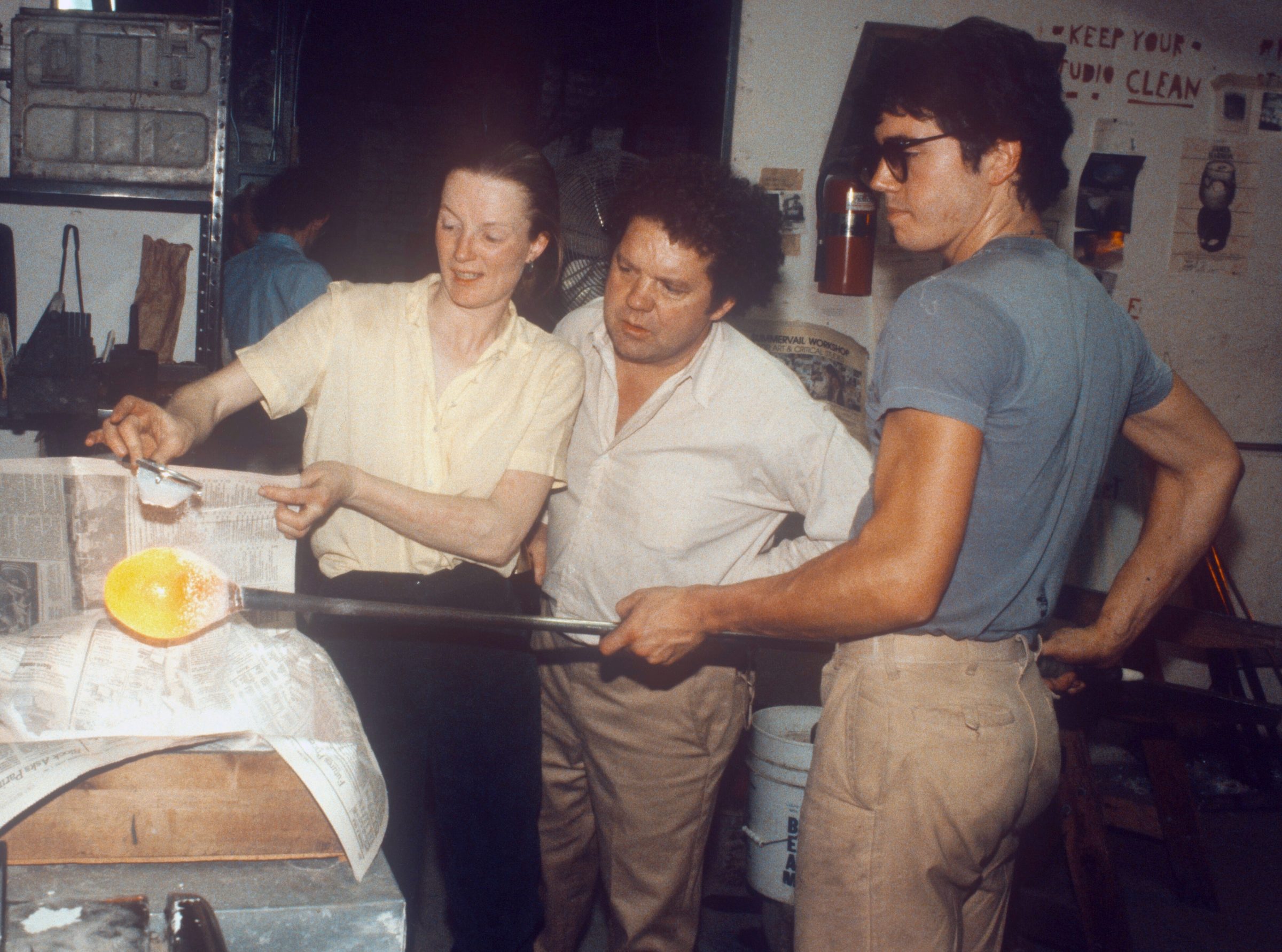

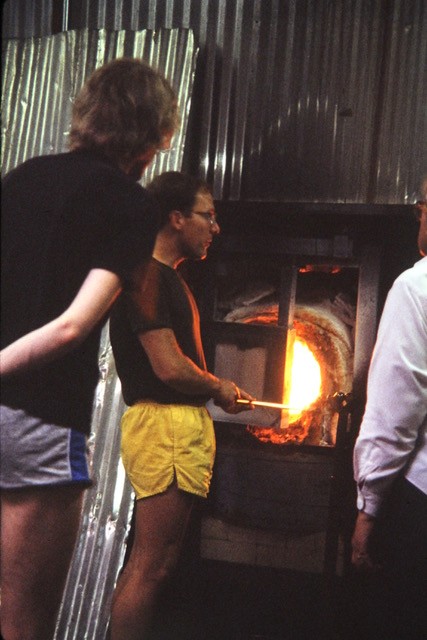

Joe Upham (left) and Richard Yelle at NYEGW, 1978. Image courtesy of Richard Yelle.

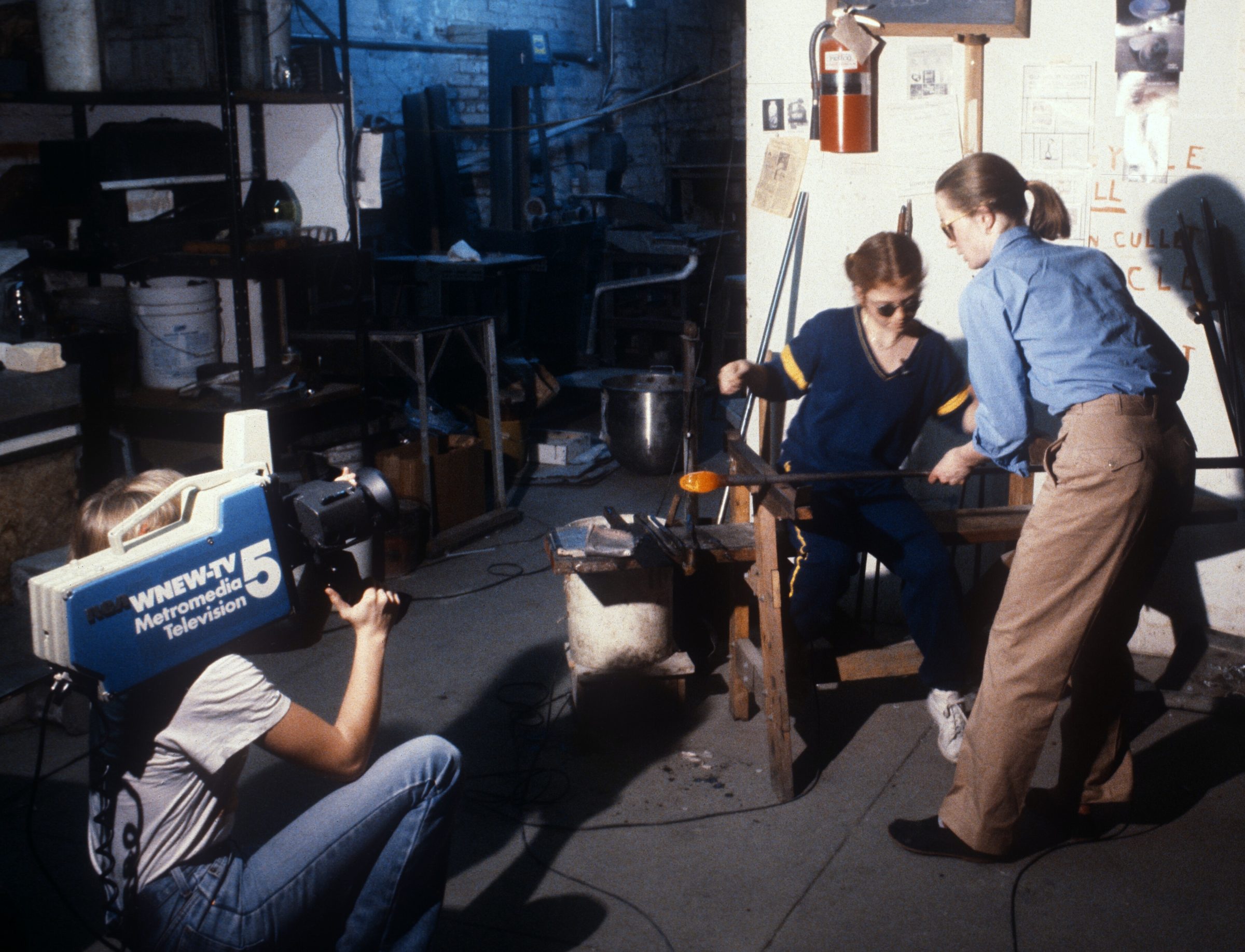

Joe Upham (left), “3, 2, 1 Contact” TV shoot at NYEGW, 1978 or 1979. Image courtesy of Joe Upham. Photo attributed to Marc Slivka.

Glassblowing class, NYWGW, 1978. Image courtesy of Joe Upham. Photo attributed to Marc Slivka.

Artist Eve Kaplan at NYEGW, 1978. Image courtesy of Joe Upham.

Toots Zynsky, Dale Chihuly and William Morris at NYEGW, 1979. Image courtesy of Joe Upham.

Toots Zynsky (standing), WNEW-Channel 5 news shoot at NYEGW, 1979. Image courtesy of Joe Upham.

Richard Yelle and Joe Upham, co-founders of New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), discuss their time together at MassArt, forming the Workshop at its first location on Great Jones Street in Manhattan, and their early public glassblowing demonstrations.

Former UrbanGlass Executive Director Cybele Maylone discusses NYEGW’s founding and early days.

02:01 Transcript

Hannah Wilke (left) with assistant Nancy Aleo at Clayworks/NYEGW, 1979. Image courtesy of Richard Yelle. Photo: Marc Slivka.

Therman Statom with Jun Kaneko’s work at Clayworks/NYEGW, 1979. Image courtesy of Richard Yelle. Photo: Marc Slivka.

“Artist Choice Exhibition” at Clayworks, Poster, 1979. Image courtesy of Richard Yelle.

Artist-in-residence Jun Kaneko (right) with Parson’s Professor Dennis Ashbaugh at Clayworks/NYEGW, 1979. Image courtesy of Richard Yelle. Photo: Marc Slivka.

“You mentioned UrbanGlass, which was actually started by Richard Yelle, who was a student at RISD…And so I was teaching…and he came to me then, he said, ‘Mary, I want to show you something.’ So I went to his apartment, and under his bed, he pulled out this little kiln, and he said, ‘I want to do a public glass place.’ And I said, ‘Wow,’ you know, ‘Fantastic.’ ‘You need some money. You need a space.’….And he is the one that really started it. It was fantastic.”

Richard Yelle discusses how he and Joe Upham put on public glass demonstrations in New York City.

02:37 TranscriptRichard Yelle discusses the history of NYEGW at Clayworks, including stories about Joe Upham, Bill Gudenrath, and Rose Slivka.

05:53 Transcript

Bill Gudenrath discusses how he first began blowing hot glass with Joe Upham at NYEGW.

02:23 Transcript

Richard Yelle talks about NYEGW’s first visiting glass artist, Patsy Novell, and first student, Bill Gudenrath.

02:31 Transcript“Well, the art/craft thing was, you know, it was an issue for educated people from the art programs and the craft programs. But I didn’t really see much interest in that from the professional artists in New York City. They just loved the fact that we were melting glass and making clay, and they just found it really interesting. And—they found it exciting.”

“New York was dirty and dangerous in the seventies. It just was. So you just had to be careful. That’s when I learned to be aware of my surroundings [laughs.].”

New Work/Glass Quarterly

New Work first issue, featuring work by Dan Dailey on cover, 1979. Gift from Richard Yelle to Bard Graduate Center.

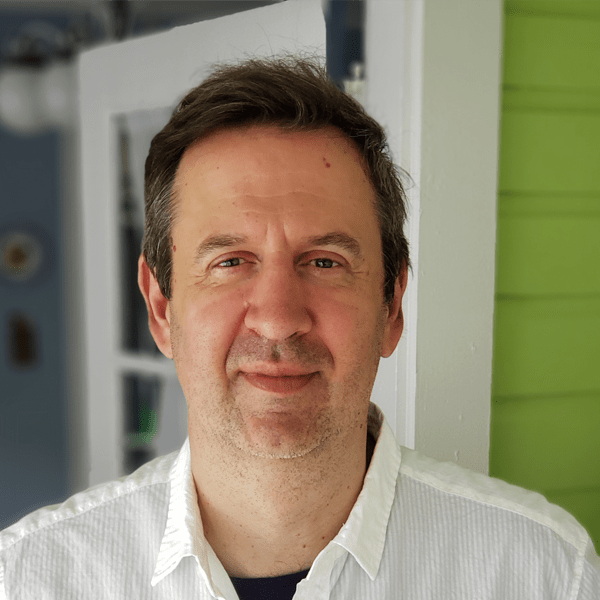

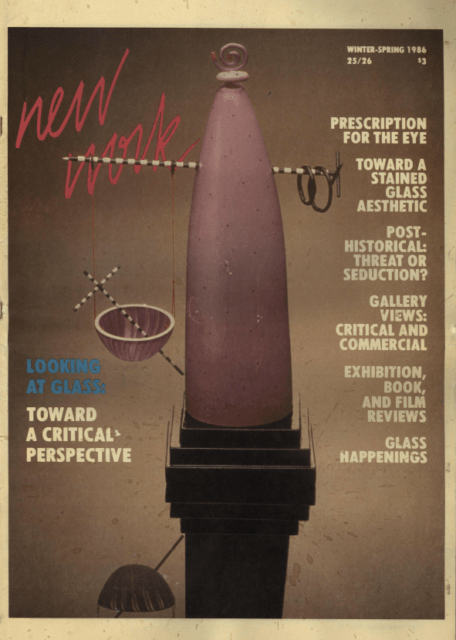

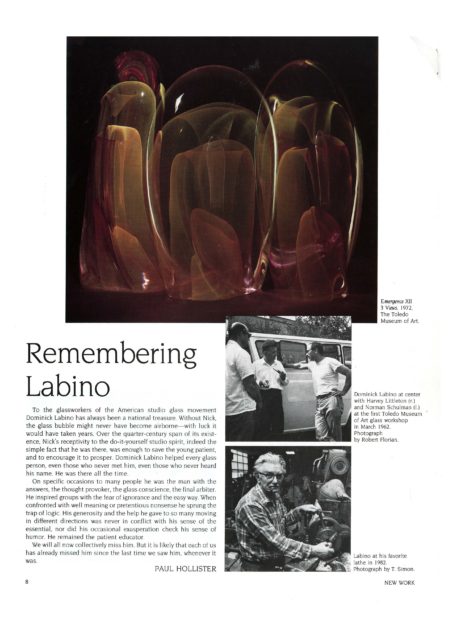

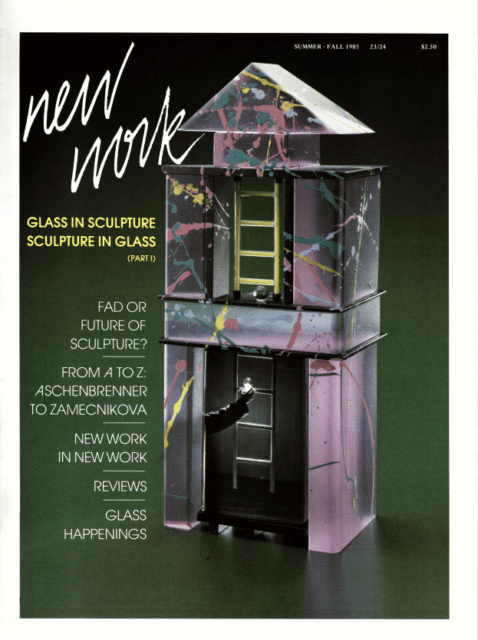

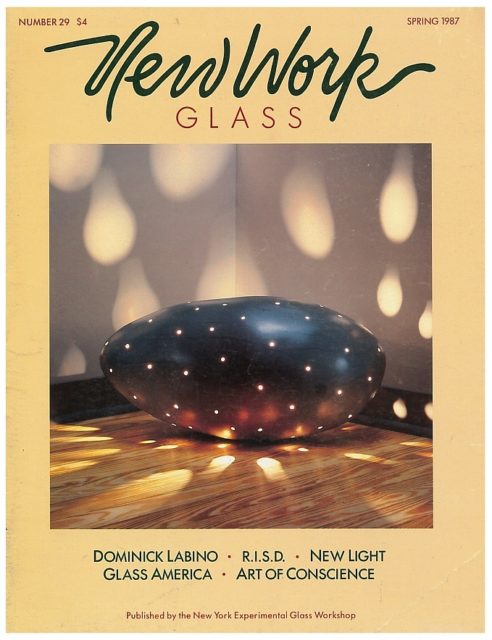

In 1979, Richard Yelle founded a periodical under NYEGW’s auspices. The magazine, which started as a newsprint publication and was initially called New Work, filled a professional void at a time when the only other magazine dedicated to studio glass was the bilingual German periodical Neues Glas. From its first issue, New Work showcased and contextualized contemporary art glass, and to this day it remains an important periodical for the contemporary glass field. Karen Chambers was the magazine’s editor from 1983 to 1986 and contributed significantly to studio glass discourse. In 1990, New Work became Glass, with a redesign by noted graphic designer/educator Michael Bierut. The full title of the magazine, published quarterly by UrbanGlass, has appeared in several variants since then, from Glass Quarterly to today’s Glass: The UrbanGlass Art Quarterly. Paul Hollister, a frequent contributor to Neues Glas, published a number of exhibition reviews, remembrances, and focused pieces in New Work/Glass from the mid-1980s through the early 1990s.

“It was great. At a certain point I knew a lot, because I reviewed anything that was glass-related in New York, and so I wrote nearly everything in the magazine, and very short reviews. At a certain time I knew everybody.”

“Prescription for the Eye.” New Work, no. 25/26 (Winter/Spring 1986): 19.

“Remembering Labino.” New Work 29 (Spring 1987): 8.

“Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová.” Glass, no. 56 (Summer 1994): 24–29.

“Reviews: Robert DuGrenier.” New Work, no. 23/24 (Summer/Fall 1985): 38.

“Reviews: Glass America 1987.” New Work, no. 29 (Spring 1987): 26–27.

“Reviews: At the Armory.” New Work, no. 30 (Summer 1987): 28–29.

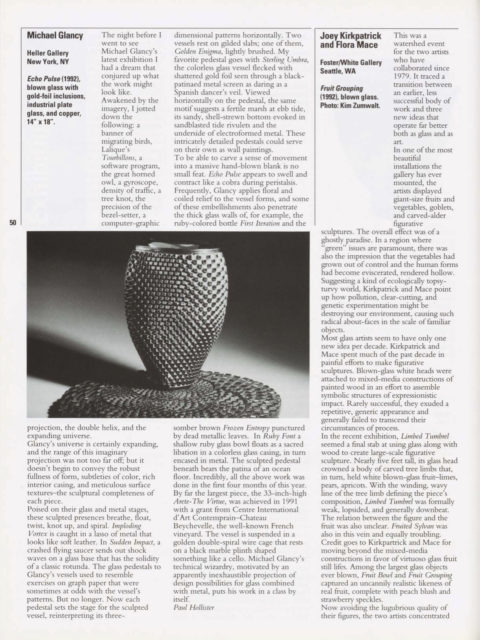

“Review of Exhibitions: Michael Glancy.” Glass, no. 48 (Summer 1992): 50.

“Obviously our origins and really our heart is based in our studio program, but I think really from our earliest days, I think Richard Yelle, one of our founders, really had an interest in not just being a place where artists were making work, but also through the initiation of the publication New Work, which is now Glass Quarterly, which started two years after our founding, there’s always been at the heart of the organization an interest in providing a platform for discourse and thinking about the material as well.”

Mulberry Street (1981–1991)

Artist Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir (left) with former New York Experimental Glass Workshop Director, Tina Yelle, c. 1980s. Image courtesy of Jame Harmon.

The Viking Tradition, Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir exhibition at NYEGW, Mulberry Street location, 1989. Work pictured: Hervör, glass, silicon, and color. Image courtesy of Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir.

“We actually had a process and a program and I give my brother Richard credit for really being the visionary in that sense, of bringing in these out-looking programs, because they were all in place when I started there. So the visiting artist [program] was competitive. We put out an application soliciting proposals every year, and there was some effort made to get applications into the hands of people like Lynda Benglis, or some people like Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir from Iceland. I don’t know exactly how we got it to her, but glass wasn’t that big a world between RISD, Pilchuck, Experimental, and a couple of other places.”

Artist James Harmon constructing tubes for work commissioned by Mobil Oil, New York Experimental Glass Workshop, Mulberry Street location, 1989. Image courtesy of James Harmon.

James Harmon, 4-panel piece installed at Mobil Oil headquarters in Fairfax Virginia, 1989. Image courtesy of James Harmon.

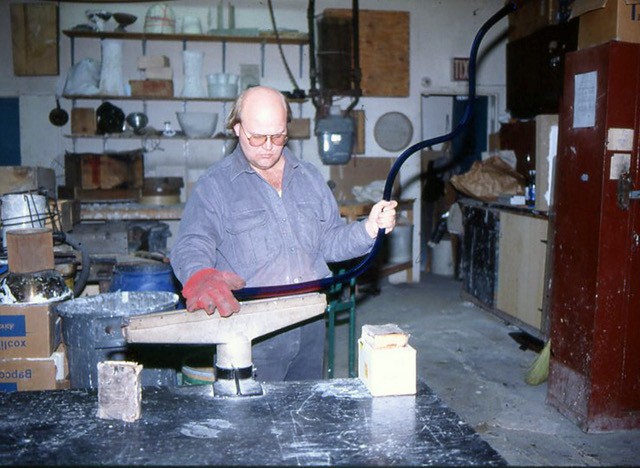

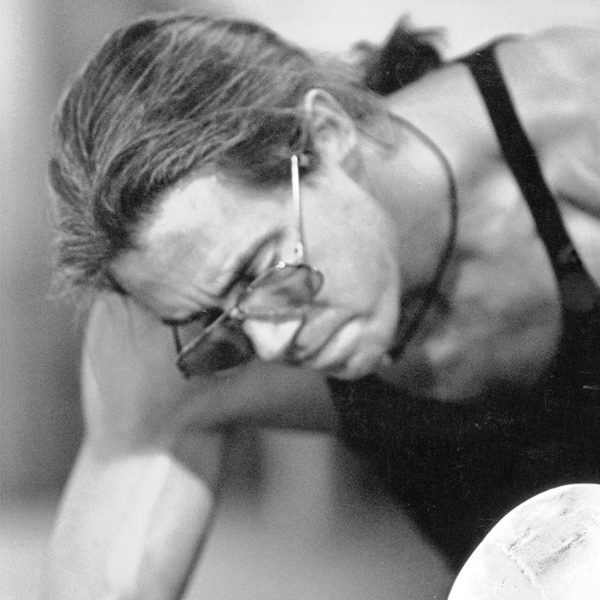

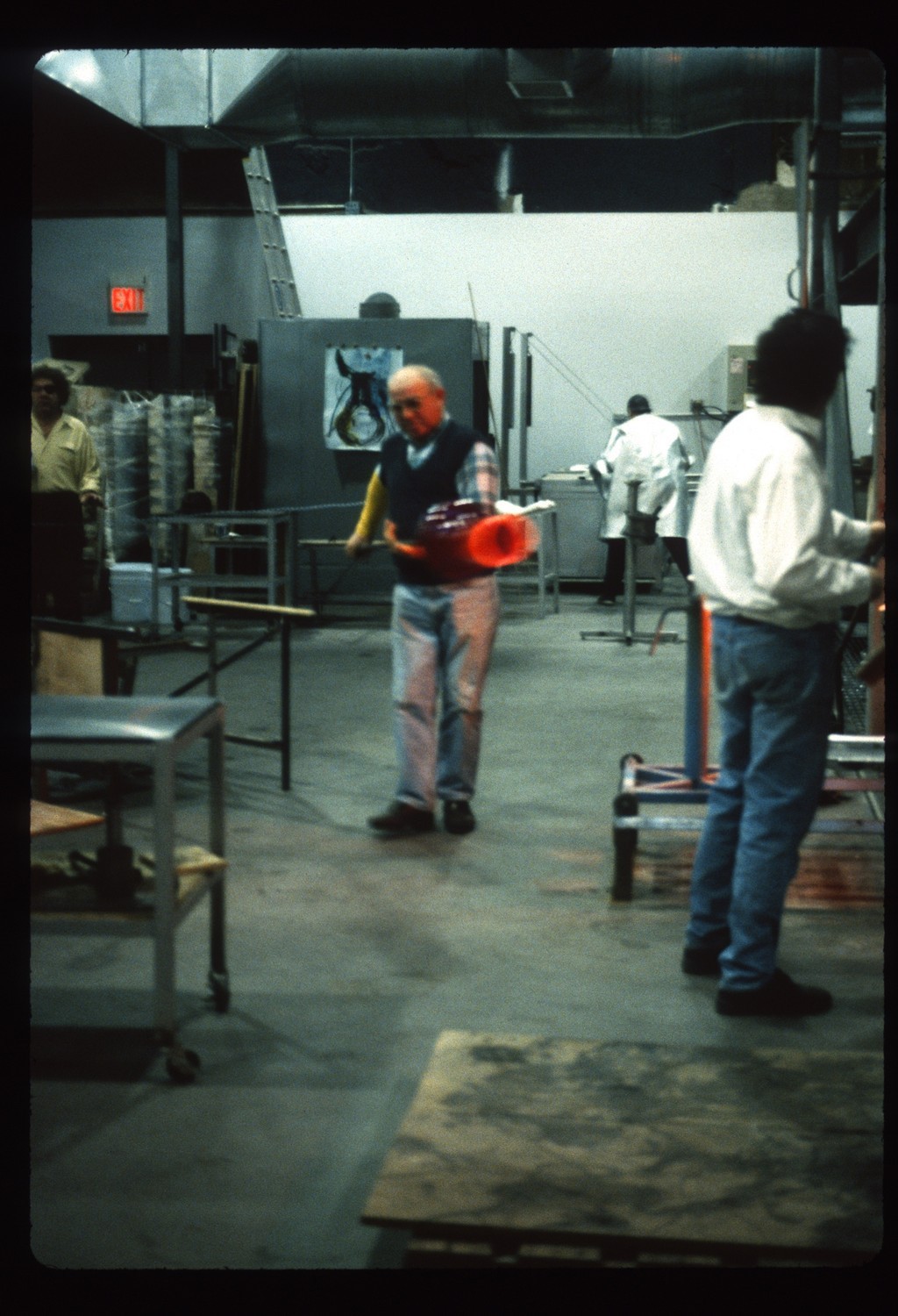

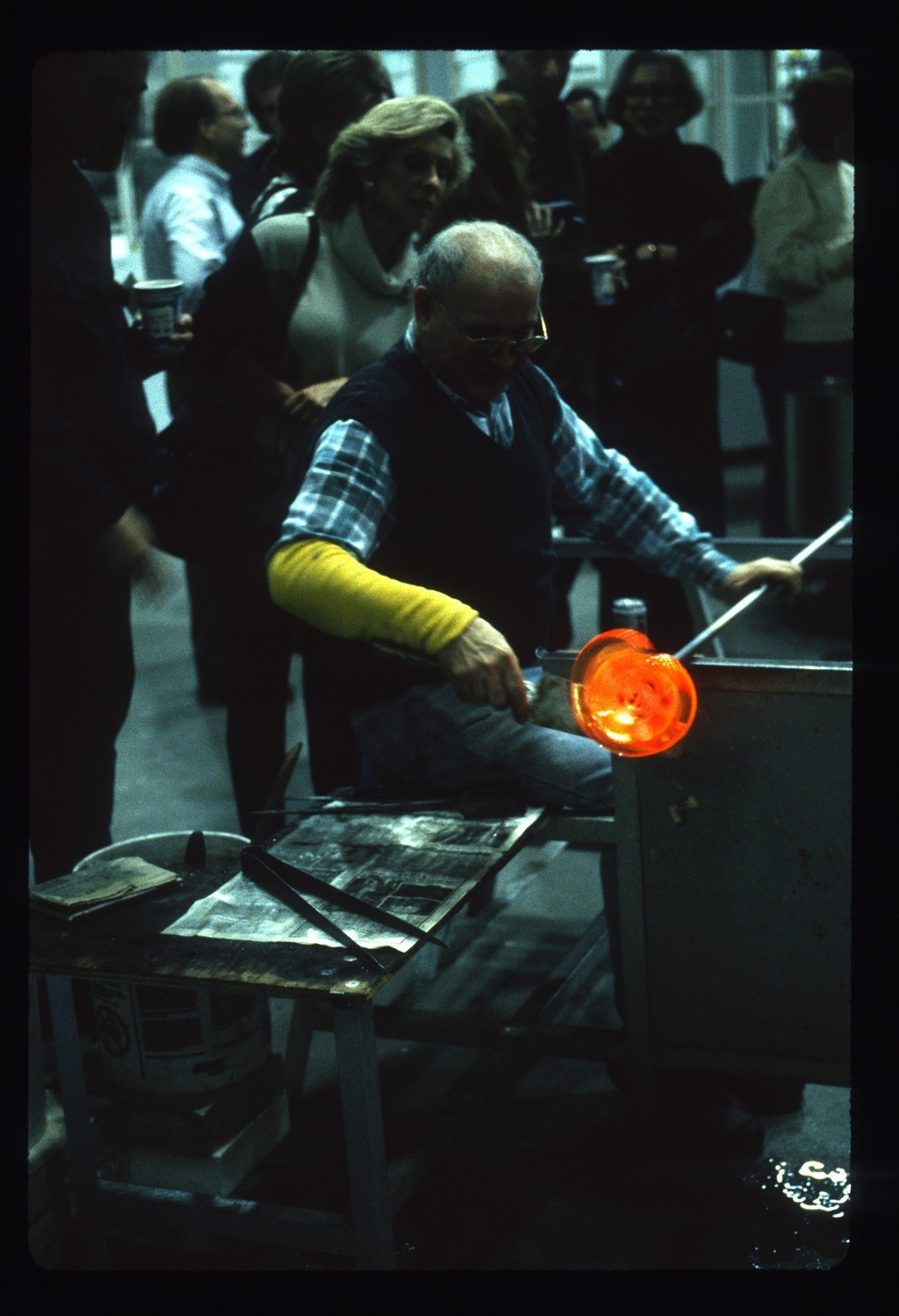

In 1981, New York Experimental Glass Workshop moved from the space it shared with Clayworks to a 5,000-square-foot facility on Mulberry Street, in Little Italy, close to the thriving SoHo arts scene—and added a gallery. Three years later, Richard Yelle brought in his sister, Tina Yelle, to take over as director. Numerous artists at the new, much-improved space volunteered to maintain the studio in exchange for furnace time, and many had their own key. Regulars at Mulberry Street included Tina Aufiero, Jane Bruce, Chris Cosma, Deborah Czeresko, Hans Frode, William Gunderath, James Harmon, Doug Navarra, and Brynhildur Thorgeirsdóttir. Contemporary artists not typically associated with glass, such as Lynda Benglis and Kiki Smith, began coming to NYEGW to integrate glass into their work. Italian artist Gianni Toso, an expert lampworker with his own studio, often came to NYEGW to blow parts for his pieces. Paul Hollister’s images of Toso using the Mulberry Street hot shop were probably shot by Hollister himself.

Gianni Toso, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1986. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Gianni Toso at the bench, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1986. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“And the neat thing about Toso, too, was he was also a master lampworker. So he could go to the lamp, and he could make things and then incorporate them into the blowing piece.”

“People don’t know this about Gianni, he’s also a master glassblower. And so he would show up at the studio and just blow glass, and it was always a trip when he was there because he’s such a character. He’s one of the oddest men I know. He’d call me up and try to marry me off or something like that, crazy like that. He was a very funny man, still is, I’m sure.”

View of New York Experimental Glass Workshop entrance at far left, Mulberry Street, New York, New York; COPYRIGHT ©2017 Glass: The UrbanGlass Art Quarterly. All rights reserved. This image originally appeared in the Summer 2017 edition of GLASS (#147). Permission to reprint, republish and/or distribute this material in whole or in part for any other purposes must be obtained from UrbanGlass.

Michael Aschenbreener, No Place Left to Hide, 1989. Made at New York Experimental Glass Workshop. Overall H: 215.9 cm, W: 165.1 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.(90.4.18).

Glass Editor Andrew Page talks about the proximity of NYEGW to SoHo and the Heller Gallery.

0:36 Transcript

Jane Bruce speaks about NYEGW at Mulberry Street and selling advertising for New Work.

01:20 Transcript

Artist Sydney Cash talks about teaching a glass-bending class for NYEGW at Mulberry Street.

00:58 Transcript“I’ve got to say, New York in the art world in the eighties—what a great time to be there.”

Tina Yelle speaks about experimentation and the culture of New York Experimental Glass Workshop during its tenure on Mulberry Street.

04:16 TranscriptTina Yelle discusses running and maintaining New York Experimental Glass Workshop at Mulberry Street.

09:28 TranscriptExpanding Glass Education in New York City

Almost from the moment it opened, the New York Experimental Glass Workshop (NYEGW) partnered with local universities to provide for-credit glass classes to art students. Glass furnaces were expensive for schools to build and maintain, and most did not have them. In 1979, when NYEGW was located on Great Jones Street, it welcomed students from Parsons School of Design and The New School for Social Research who wanted to learn glassmaking. But it wasn’t until the move to Mulberry Street that partnerships became formalized. Before that, artist Mary Shaffer, who taught craft-based courses at New York University (NYU) from 1980 to 1983, engaged artist John Brekke to give a public glassblowing demonstration to recruit students to her classes. Shaffer was a consultant for a slumping, or glass-bending, studio at NYU; however, it soon became apparent that the university’s facilities were not adequate for that. Eventually, Judith Schwartz, then Director of NYU’s Craft Department, approached Tina Yelle about creating a broader glassmaking experience for students exclusively at NYEGW. In 1984, Schwartz began negotiating contracts with the Workshop, and NYEGW soon offered full survey classes, including neon, glassblowing, and sand casting. Artist James Harmon taught the first class, followed by Jane Bruce, who taught there for nearly a decade. Starting about 1990, undergraduates at Parsons could earn a BFA in glass through NYEGW, in a program that lasted about 10 years.

Glassblowing demonstration by John Breeke to recruit students to Mary Shaffer’s classes (Mary Shaffer’s daughter, Maiya Keck, pictured in front), New York University, 1980. Image courtesy of Mary Shaffer.

Artist and instructor James Harmon (at left, in white) with NYU Students at New York Experimental Glass Workshop, 1985. With Harmon, Fred Kahl (at right, in gray) assisted the 1992 NYEGW Chihuly Venetians demonstration photographed by Paul Hollister. Image courtesy of Judith Schwartz.

NYU Students at New York Experimental Glass Workshop, 1985. Image courtesy of Judith Schwartz.

“I taught the first, I don’t know, five years of [the NYEGW NYU program], and really got it off the ground. Jane Bruce was involved. [She] had just arrived from England, and it took a while for her to get her feet, but once she did she loved teaching, and she took over the program from me, actually. She really ran it for a long time after I did.”

Fred Kahl discusses being a New York University student and studying glass at NYEGW.

02:55 Transcript

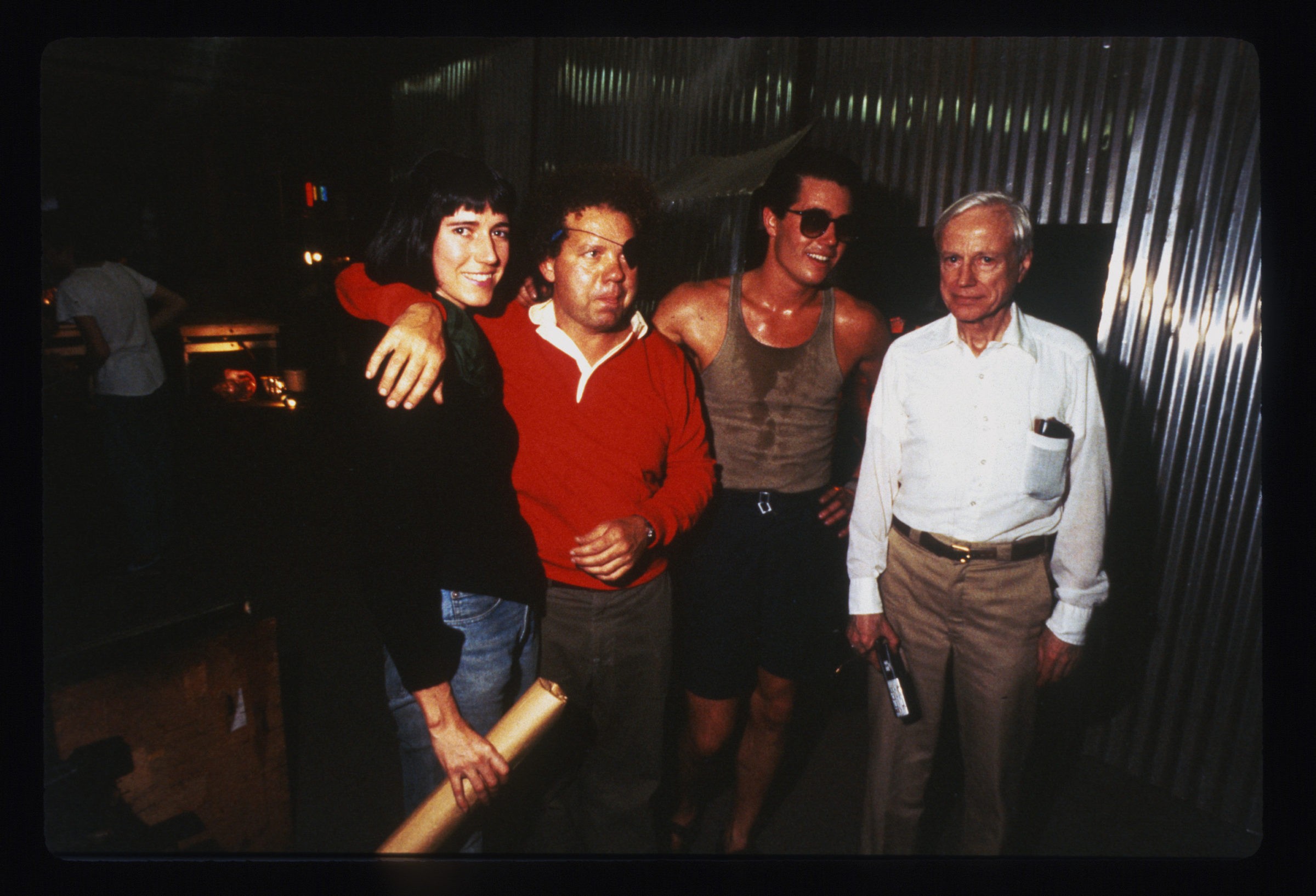

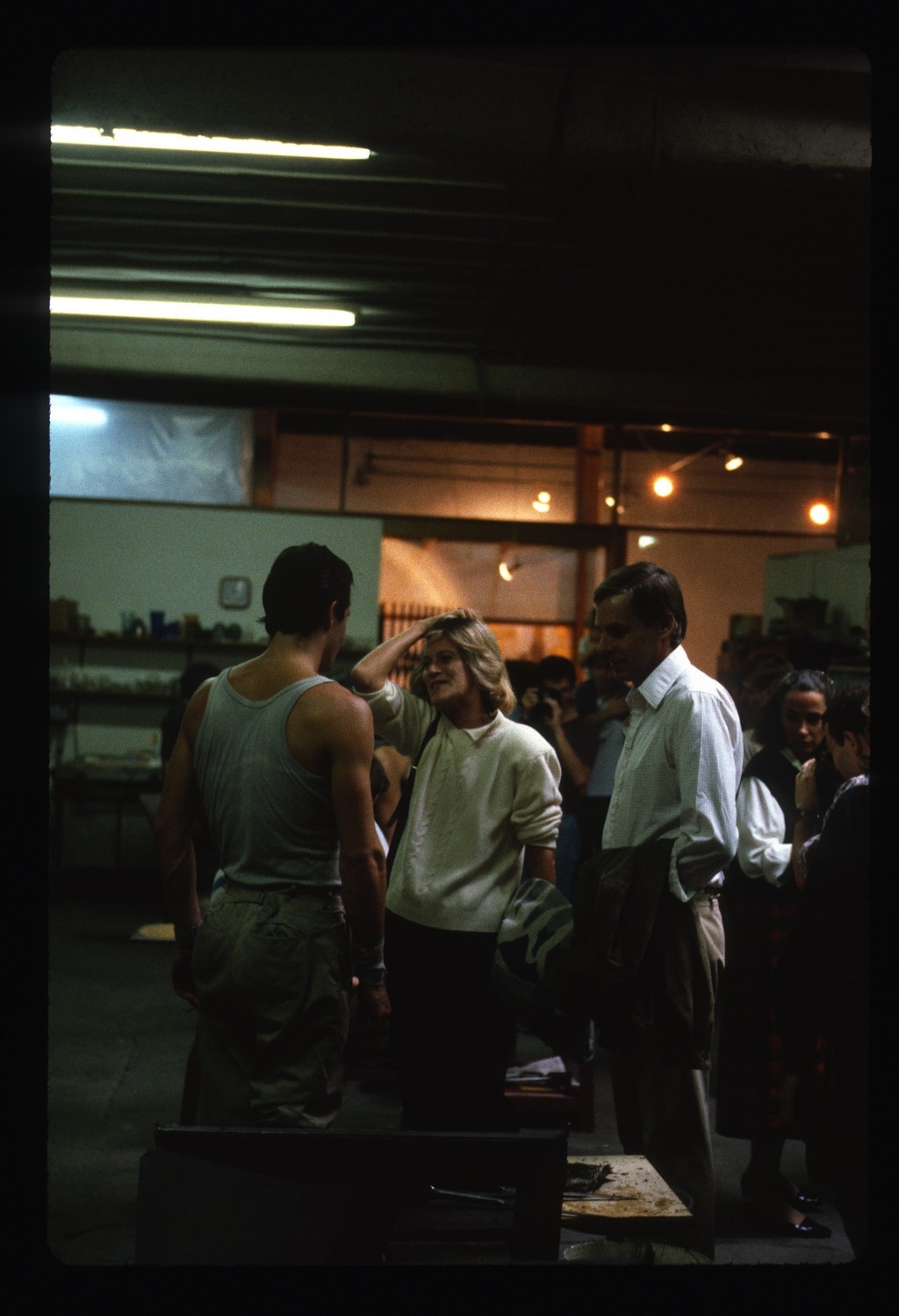

Eve Vaterlaus, Dale Chihuly, William Morris and Paul Hollister at the Macchia Demonstration at New York Experimental Glass Workshop, Mulberry Street, New York, New York, 1985. Photo: Edward Claycomb.

1985 Dale Chihuly Macchia Series Demonstration

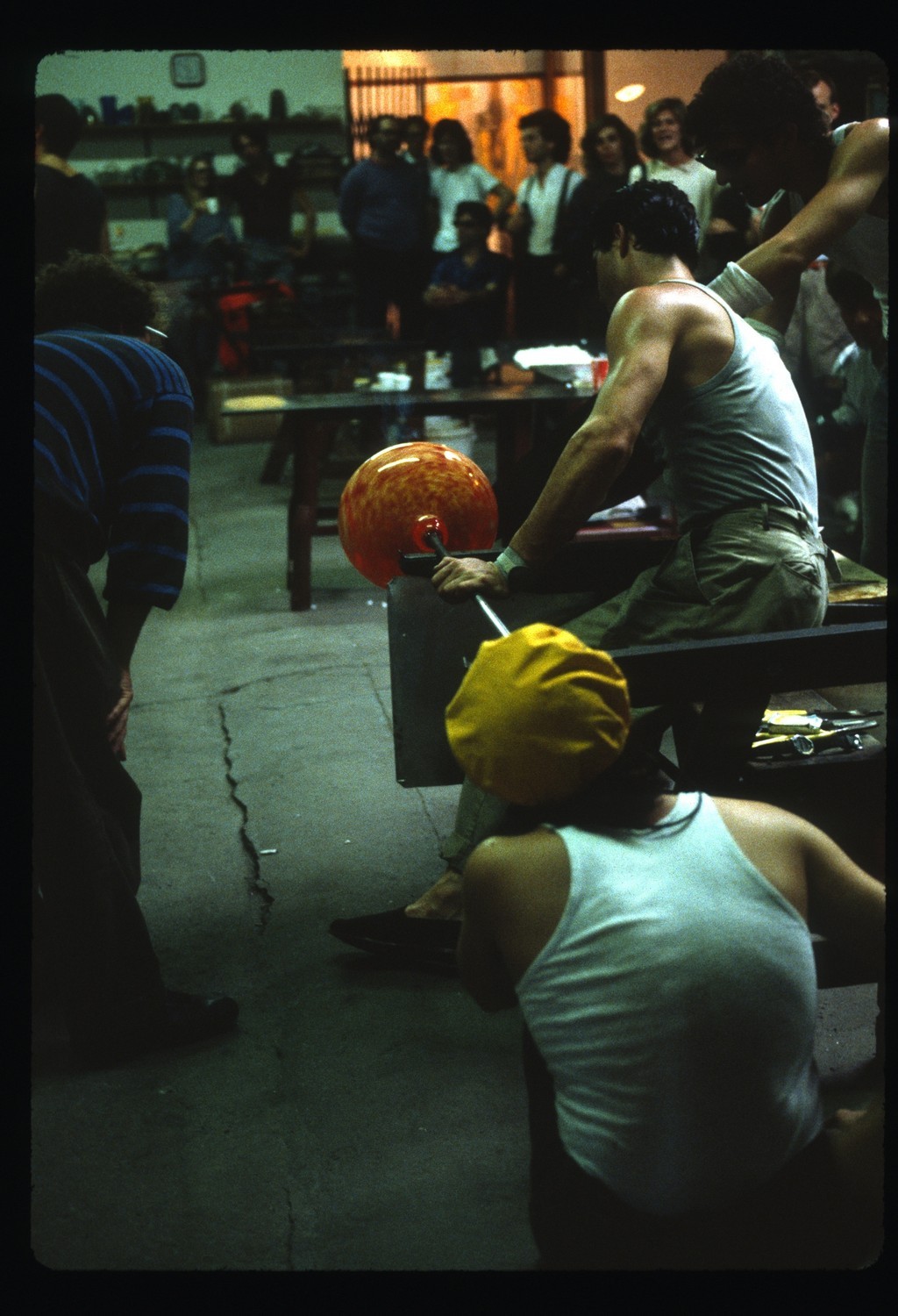

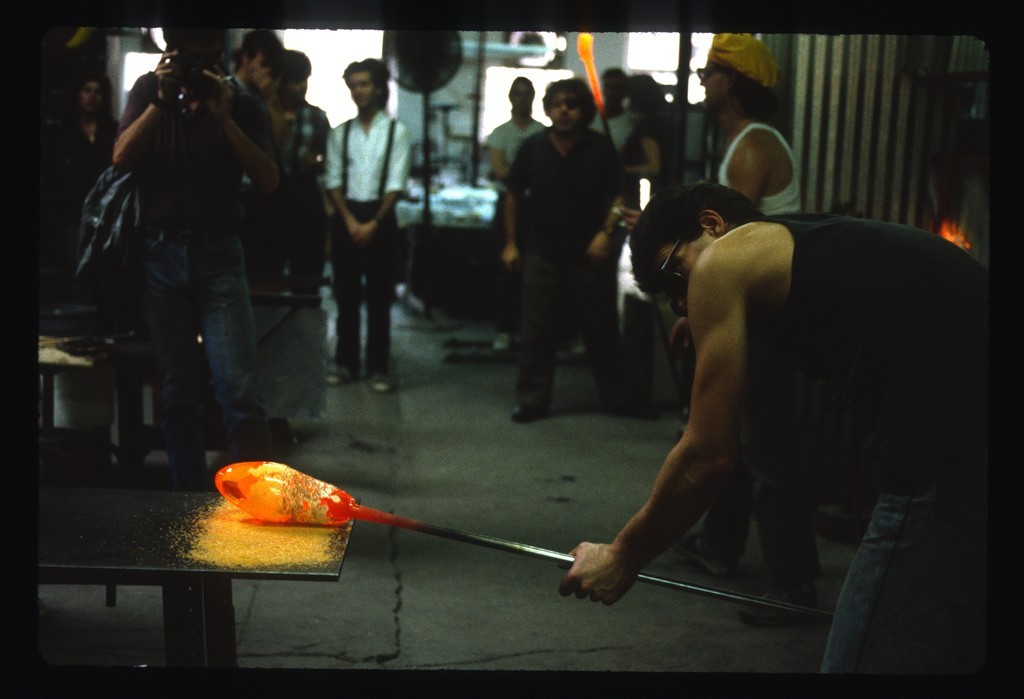

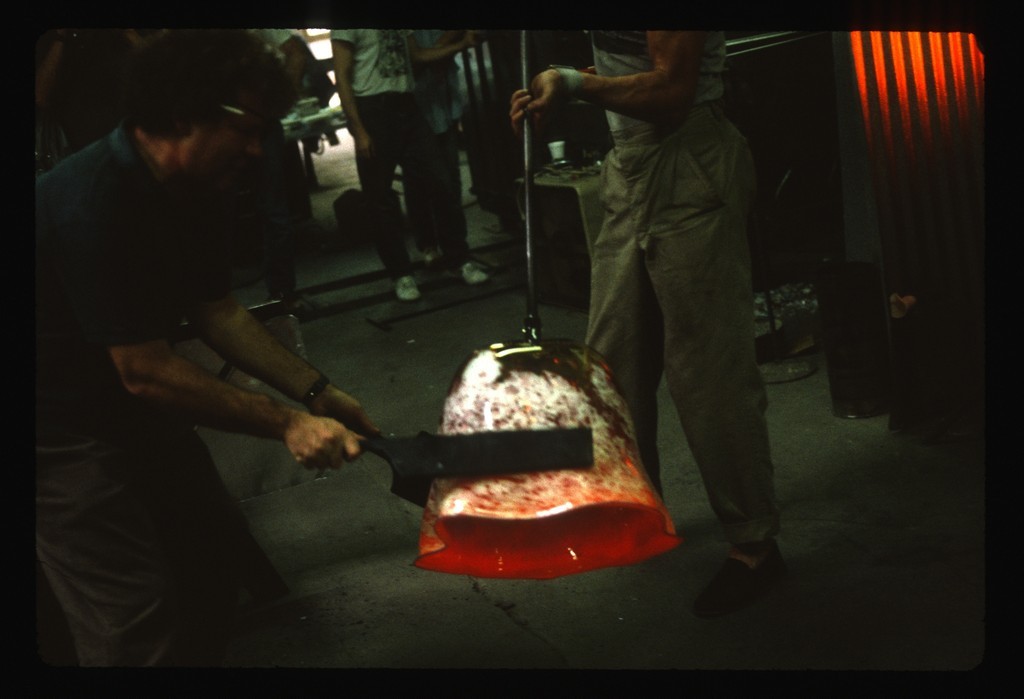

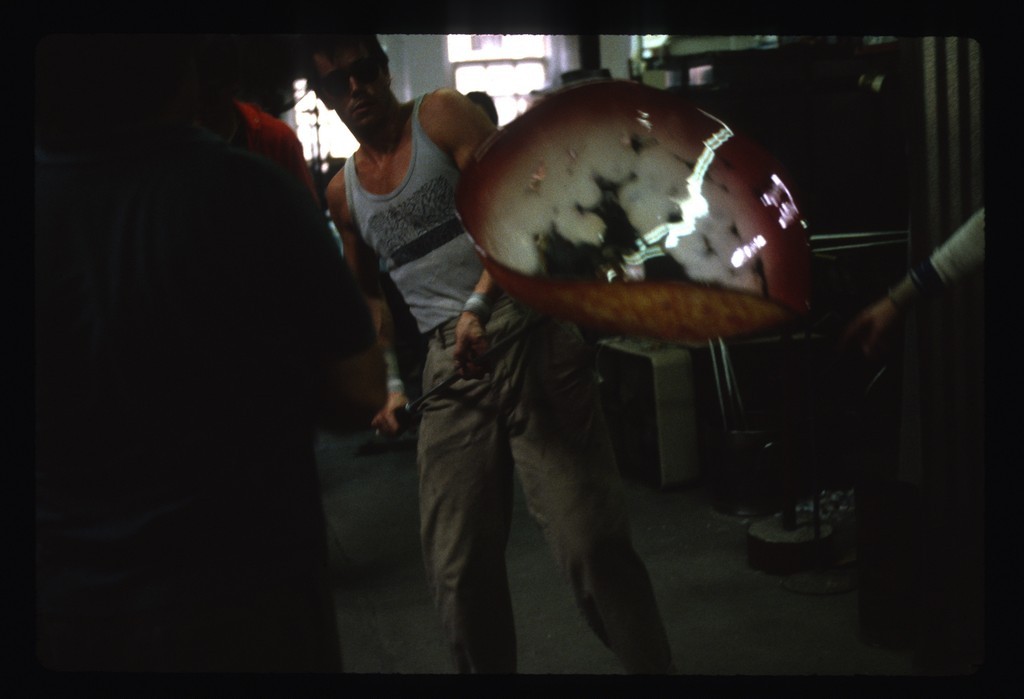

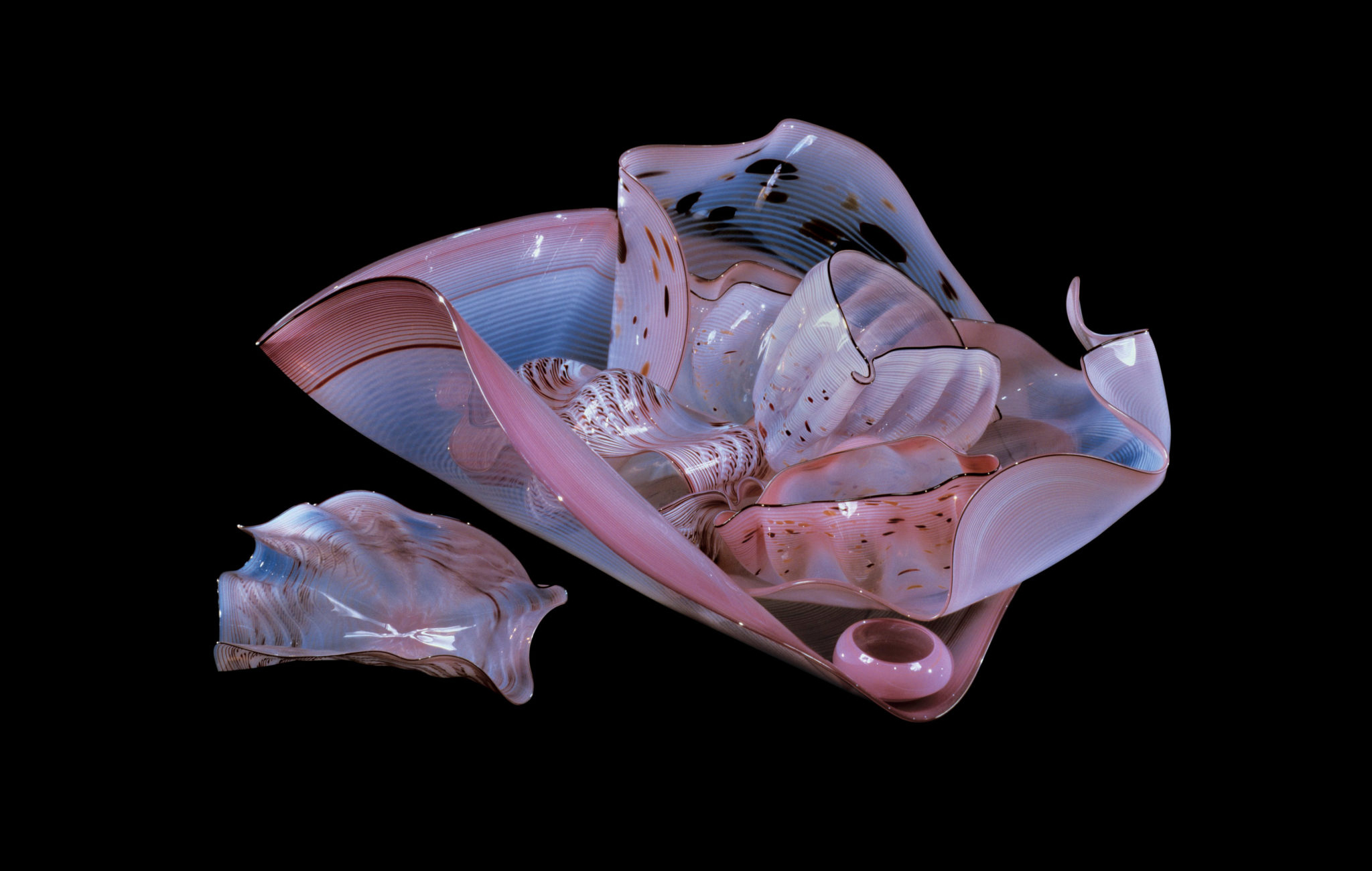

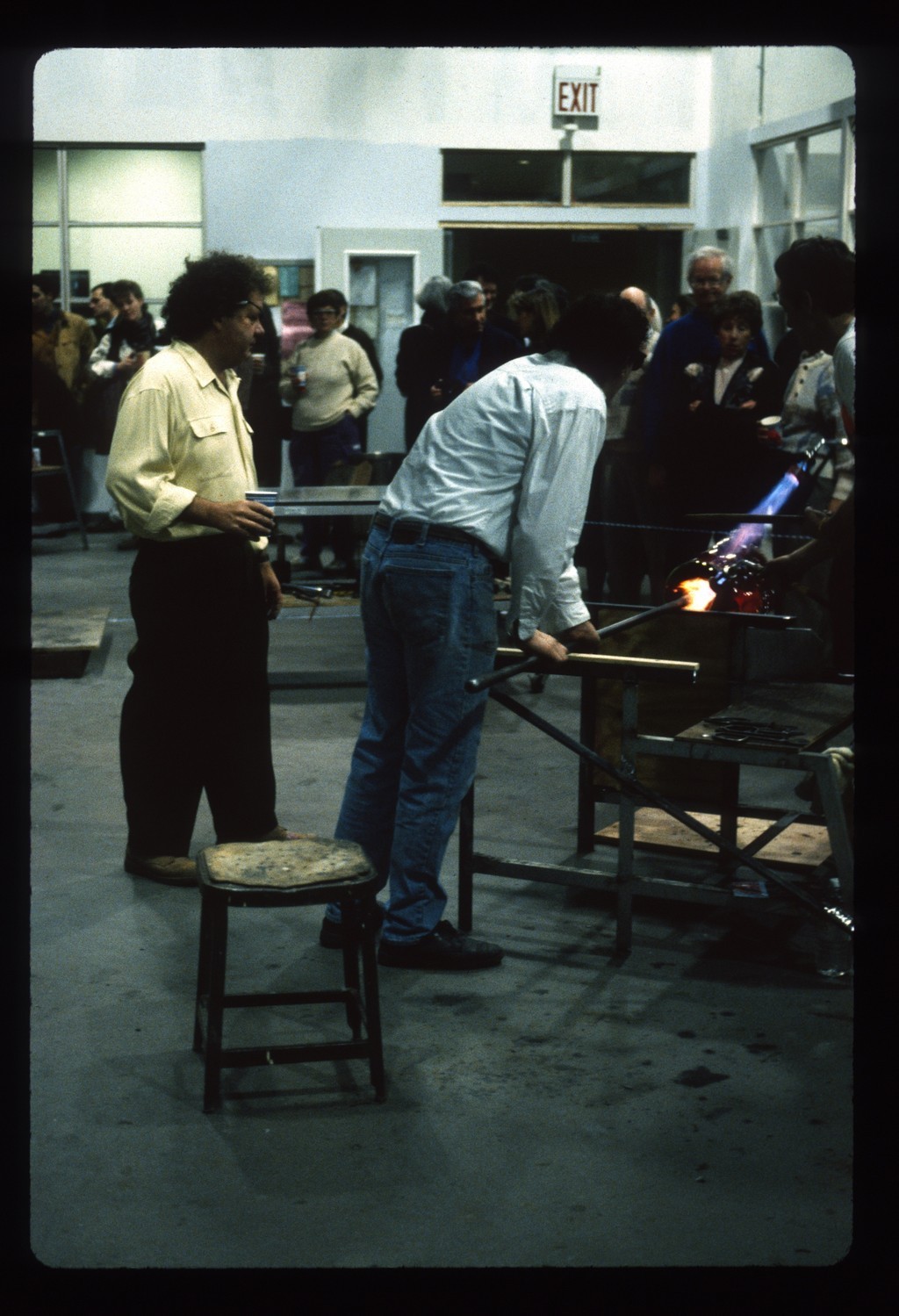

In 1985 the artist Dale Chihuly held his second workshop at New York Experimental’s Mulberry Street location. As with the first, given in 1983, the weekend residency attracted artists and collectors as well as the general public, who watched Chihuly and his team blow objects for his Macchia series, named for the brightly colored chips of glass that impart a speckled effect. Chihuly was already well known, having founded the influential Pilchuck Glass School in the early 1970s. He successfully positioned his own glass objects in the wider contemporary art world through such venues as the Charles Cowles Gallery, in SoHo, which began showing Chihuly’s work in 1981. In the first half of the 1980s, NYEGW was still young and developing as a studio space. Hosting an artist as established as Chihuly bolstered its reputation. The Pilchuck team, which included Larry Jasse, Ann Wåhlström, and Chihuly’s then-chief gaffer William Morris, helped expand NYEGW’s technical capabilities by sharing their artistic skills and knowledge of equipment standards. One of NYEGW’s own artists, Paul DeSomma, assisted and was later invited to work with Morris in Seattle.

In December 2004, soon after Paul Hollister passed away, his widow, Irene Hollister, attached a note to the original 35mm sides Hollister had taken of the 1985 session (pictured below), remarking on their significance and suggesting that glass artist William Gudenrath, a close friend of Hollister’s, put them in sequence. Hollister had made audio recordings at the 1983 workshop. At that time, he was not yet familiar with everyone on Chihuly’s crew, and he recorded his own notes about them as well as his conversations with Chihuly, Jasse, Morris, and Wåhlström.

In this 1982 interview with Paul Hollister, William Morris discusses working with molds for his large-scale pieces.

08:45 Transcript

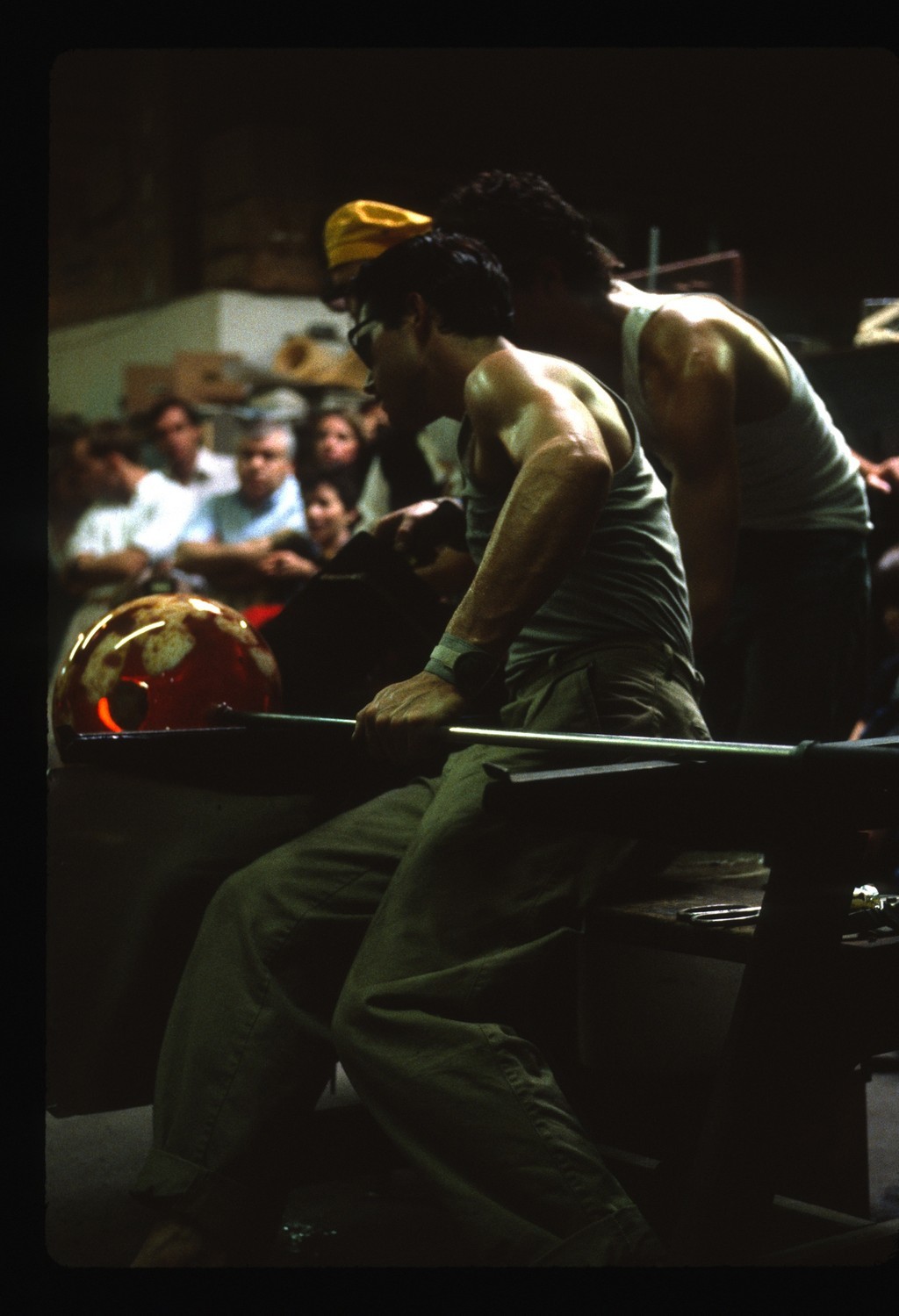

Dale Chihuly (left), William Morris at the bench, Paul DeSomma (upper right), Larry Jasse (yellow hat), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“It was a fantastic place as far as I was concerned. I mean, I had very little exposure to other studios. It was this one, [and] it was the one I worked in Ohio with Jane Bruce. She was at Ohio University in Athens, southeast Ohio, and that was actually a significant studio in that I think it was first founded by Fritz Dreisbach, who’s one of the senior leaders of the studio field. But I was all pretty wide-eyed cause it was, you know, this was New York City, this was Heller Gallery. They showed all the big names, and here I was getting a chance to work with the top. You know, it was again a style of working I hadn’t really been exposed to, and they pretty much put me on the bottom of the team so I could not screw anything up [laughs] I mean, I didn’t even bring a punty to transfer a piece from blowpipe to the finishing steps until about the third time I worked with them in Rochester. So it took some getting used to me…”

“Tank tops. Yeah, that was our uniform back then.”

William Morris at the bench, Paul DeSomma (behind), Ann Wåhlström (left background in black and white shirt), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris at the bench, Paul DeSomma (standing), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“I had met Paul [DeSomma] for the first time–he was working at the Heller Gallery [New York, New York], and I remember he was packing and setting shows and stuff for them and that’s how he got the ‘in’ to start working with us.”

Dale Chihuly (right), Wiliiam Morris at the bench, Larry Jasse (yellow hat), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris (front, applying frit to molten glass for Macchia), Larry Jasse (right, yellow hat) and Dale Chihuly (center background), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Larry Jasse (yellow hat) with William Morris at the bench (included in background: Wolfgang Buchner, seated, gray sweatshirt; Doug Navarra, standing, maroon t-shirt), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris at the bench, Paul DeSomma (upper right), and Larry Jasse (top, yellow hat) working Macchia, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dale Chihuly (right) overseeing William Morris (at the bench), Larry Jasse, and Paul DeSomma adding lip trail to Macchia, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Larry Jasse, Paul DeSomma and William Morris (at the bench) adding lip trail to Macchia, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dale Chihuly (left) and William Morris working on Macchia, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris spinning Macchia vase on pontil, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris lifting Macchia on pontil, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dale Chihuly (left) inspecting Macchia on pontil held by William Morris, Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris (left), Dale Chihuly Macchia Series demonstration, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Mulberry Street Location, New York, New York, 1985. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

William Morris and Paul DeSomma speak about their involvement in Dale Chihuly’s 1985 Macchia demonstration at New York Experimental Workshop. Throughout the images, Chihuly is assisted by Morris, DeSomma, Larry Jasse, and Ann Wåhlström.

Transcript“Well—Tina [Yelle] was the director at the time, so I was just a board member, but I lived a couple blocks away and this was a big deal for us, you know, to attract somebody like Dale, who was used to having better facilities and good glass. But it was mutually beneficial, because he had a lot of potential collectors in New York City. And we were the only [laughs.] show in town. And so, literally, he had to blow glass at the Glass Workshop. And so we did our best to accommodate him and make sure that everything was running, the glass was at its best, and so on and so forth. And these events were really popular, not only with collectors, but also—to a certain extent with the general public. And then with the artists themselves and especially the ones that worked full time that are at the Glass Workshop. So it was all good.”

Chihuly team for the 1985 Macchia demonstration, Mulberry Street location of New York Experimental Glass Workshop, New York, New York; left to right: Larry Jasse, Ann Wåhlström, Dale Chihuly, Billy Morris, Robert Carlson, unidentified. Image courtesy of Larry Jasse. Photo attributed to Mary Laurence.

Dale Chihuly, Macchia Seaform Group, 1982. Made with the assistance of Benjamin Moore and William Morris. Optic-blown, hot-worked glass. Overall W (max): 64. 2 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass. Gift of Michael J. Bove III. (83.4.45).

From Manhattan to Brooklyn

In 1991, with incentives from the New York Economic Development Corporation, New York Experimental Glass Workshop moved to Brooklyn and dramatically increased in scale. NYEGW raised millions of dollars to renovate the third floor of the former Strand Theatre, developing a 12,000-square-foot studio, gallery space, and a small store. With this move, the Workshop effectively transitioned from a fledgling artists’ cooperative into a highly professional nonprofit arts organization. In 1994, NYEGW changed its name to UrbanGlass. Tina Yelle left for Boston in 1995, and John Perreault succeeded her as executive director (1995–2002).

Reception while new building was being renovated, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn location, New York, New York, 1990. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Jane Bruce discusses the transition from NYEGW’s Mulberry Street location to Brooklyn.

01:13 Transcript

“We opened up shop in late ‘91…if I remember right. For a small organization, it was a big undertaking taking over a 17,000 square-foot space and raising money and building it and, of course, as artists and board members who don’t know much technology we were kind of naive. We walked in there and saw the 50-foot ceilings and were like, ‘Oh great, it’s never gonna get hot in here.’’ Well it did get hot because of the general humidity in New York and the heat in the summer. And the part we didn’t think about is, in the wintertime it actually got really cold because the heat would just go right up to the ceiling and the floor would be pretty damn cold. And so it was kind of an interesting transition, but the old studio was so bad that it was just so nice being able to go and work in there with decent glory holes and decent furnaces and open space.”

“We needed to keep our books clean and we needed to do a lot of other things at this point because we’re getting money from larger organizations. We’re getting large grants at this point from the government, so it was very important that we do things like a normal place would. We weren’t just this piddly little studio anymore.”

Raw space to become new NYEGW in former Strand Theatre, Brooklyn, New York. Image courtesy of UrbanGlass, Brooklyn, New York. Photo: Marc Bryan-Brown.

“And of course we wanted bigger and better. And when we looked at the space, that 20,000 square-foot big empty space with 60 foot ceilings, it was just—yeah, we want it. And we had this talent—like Jeff Beers and Michael Bierut. We had talent.”

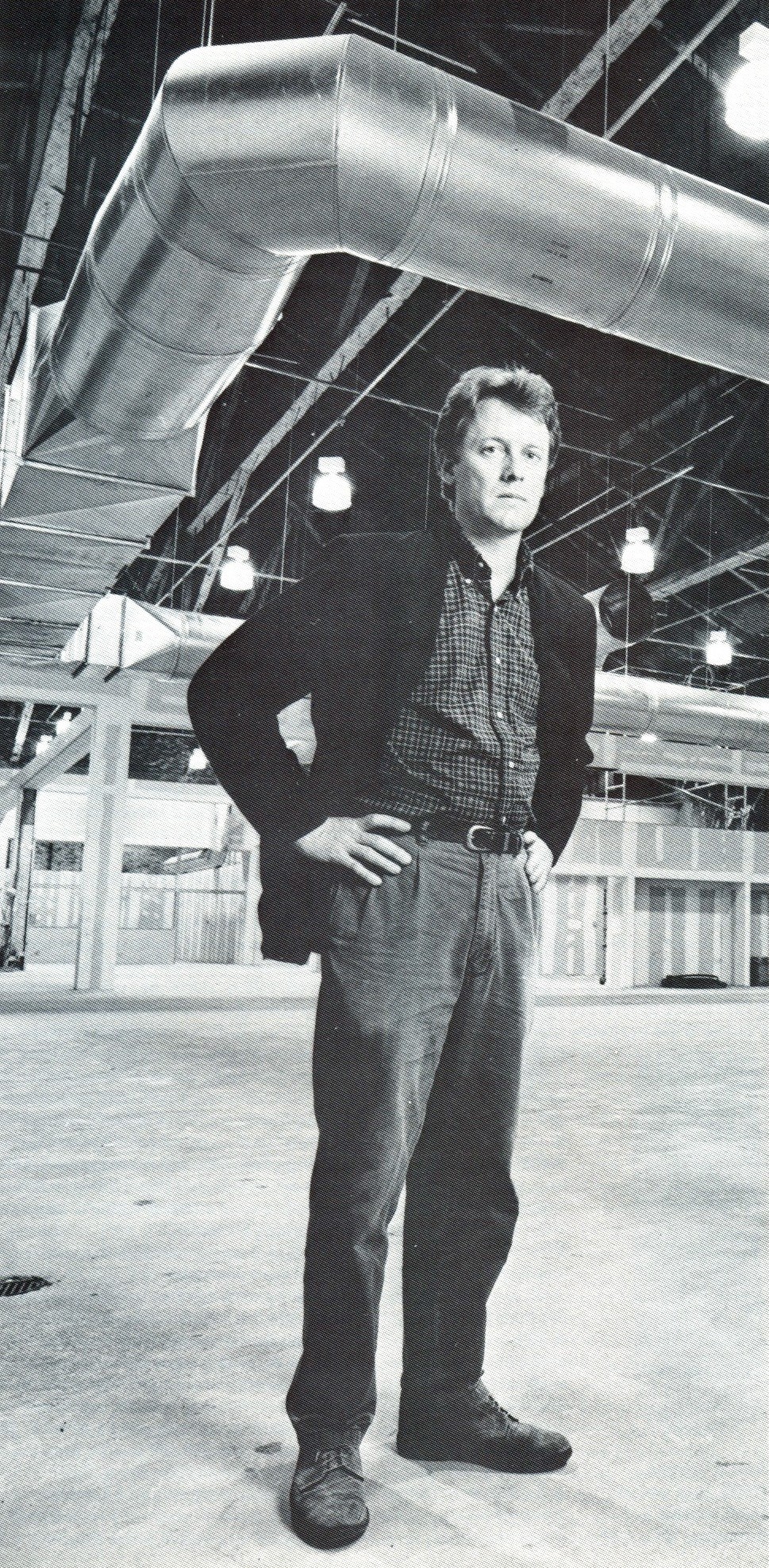

Richard Yelle in Strand Theatre while under construction. In Glass Magazine, 1989 issue #41, p. 12. “Conversation, Richard Yelle & Michael McTwigan.” Photo: Marc Bryan-Brown.

Tina Yelle, Geoff Isles, James Harmon, Jane Bruce and Fred Kahl discuss NYEGW’s transition from Manhattan to Brooklyn.

8:48 Transcript

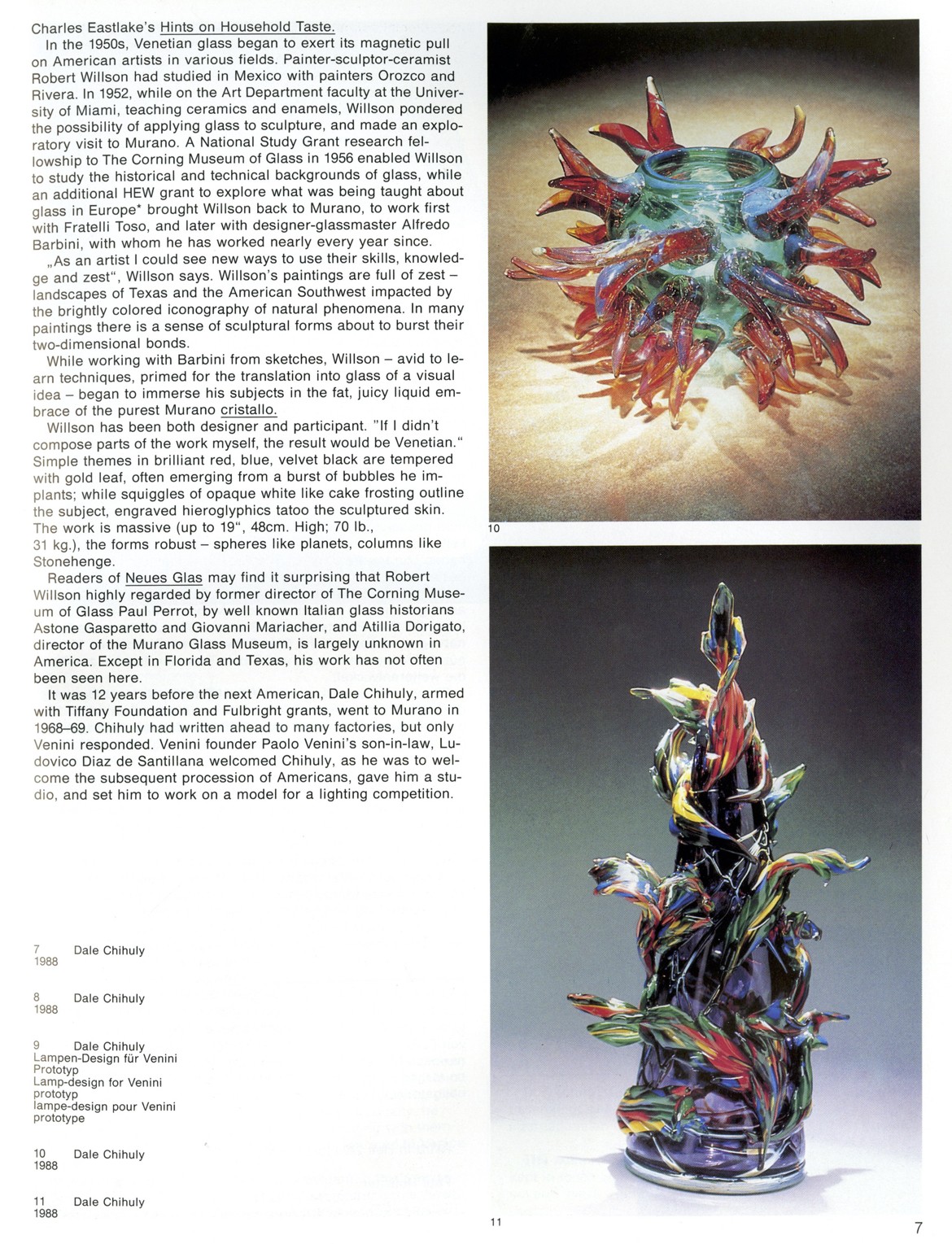

1988 Dale Chihuly Venetian series work, bottom illustration. In Paul Hollister, “The Pull of Venice/Die magische Anziehung Venedigs,” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1990): p. 7.

“At this point [Dale] was doing a series called The Venetians with Lino Tagliapietra [as] the gaffer for it— sort of as a guest gaffer. At this point Martin Blank would be his primary gaffer once they’re not in front of the cameras, and when they’re in the studio Martin Blank would be his main gaffer and Robbie Miller would be the other person assisting, and there were other people as well. So this was just a general sort of demo day production that was beneficial for [Dale] as well. And collectors would come in or just the general public. This particular one looks like collectors just because of the crowd. And they would come and watch demos being done.”

1992 Dale Chihuly Venetian Series Demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra

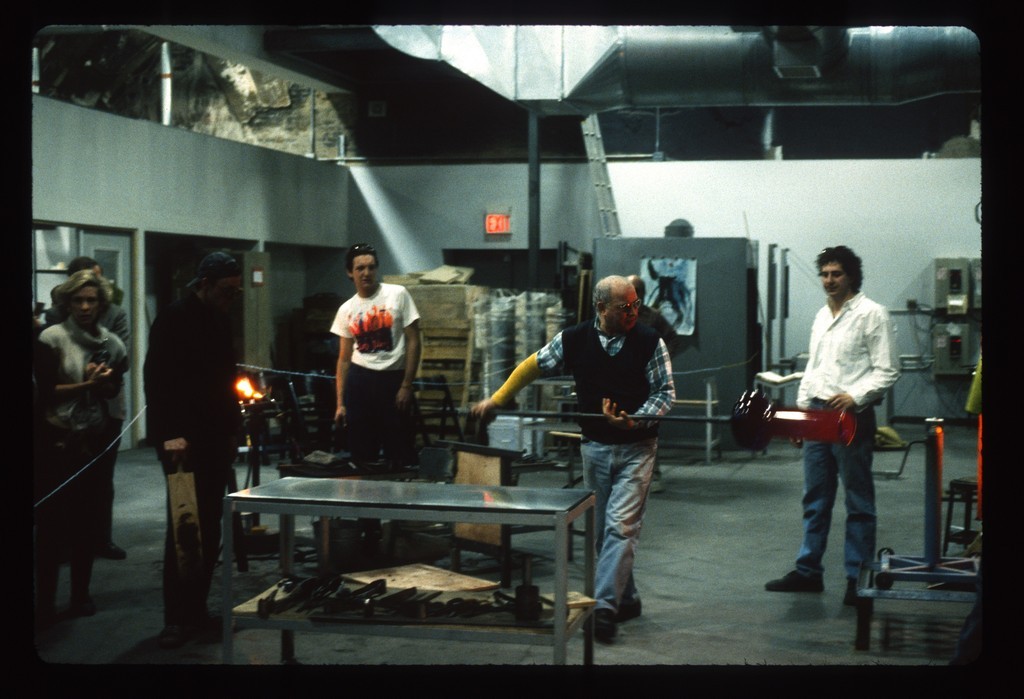

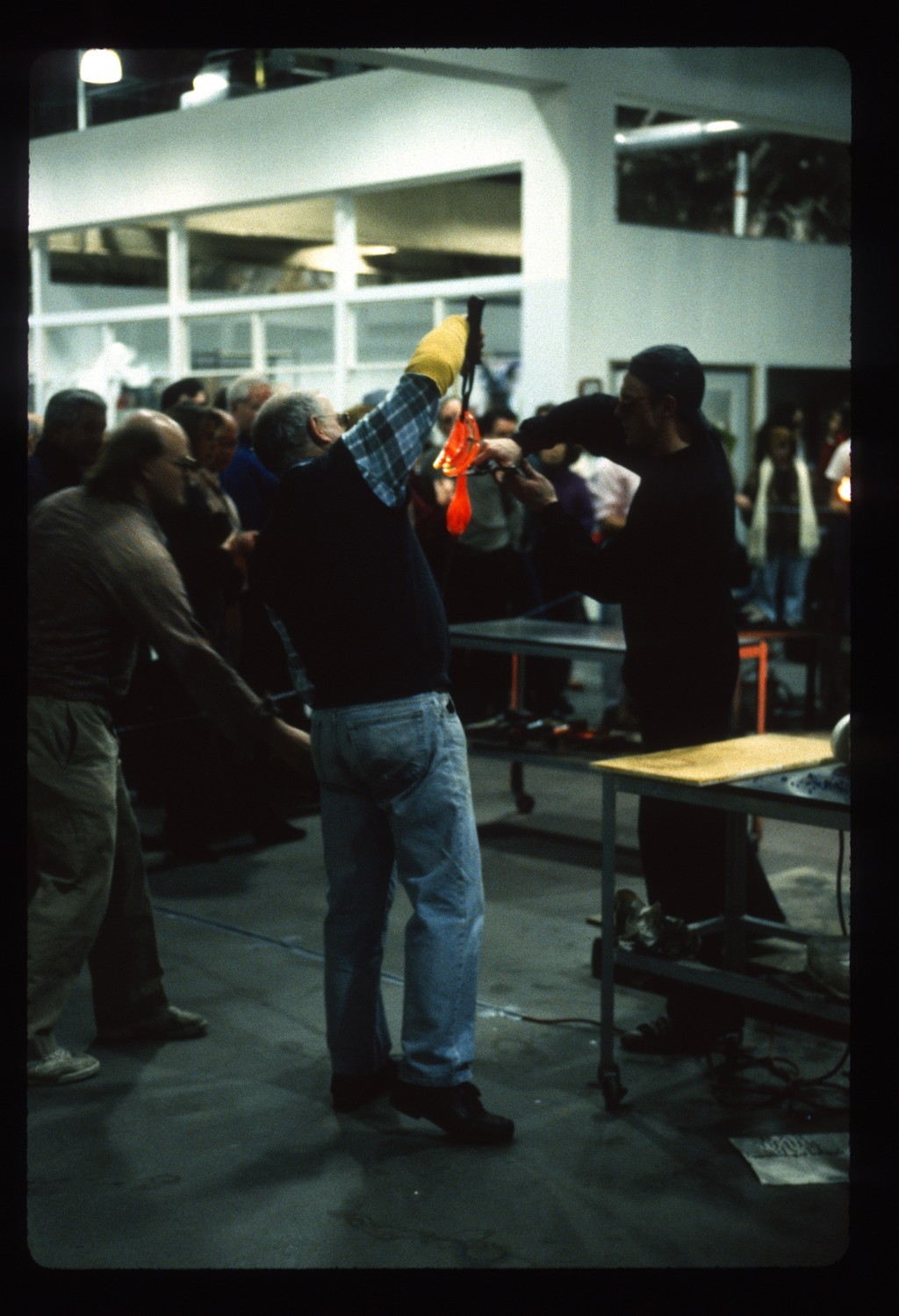

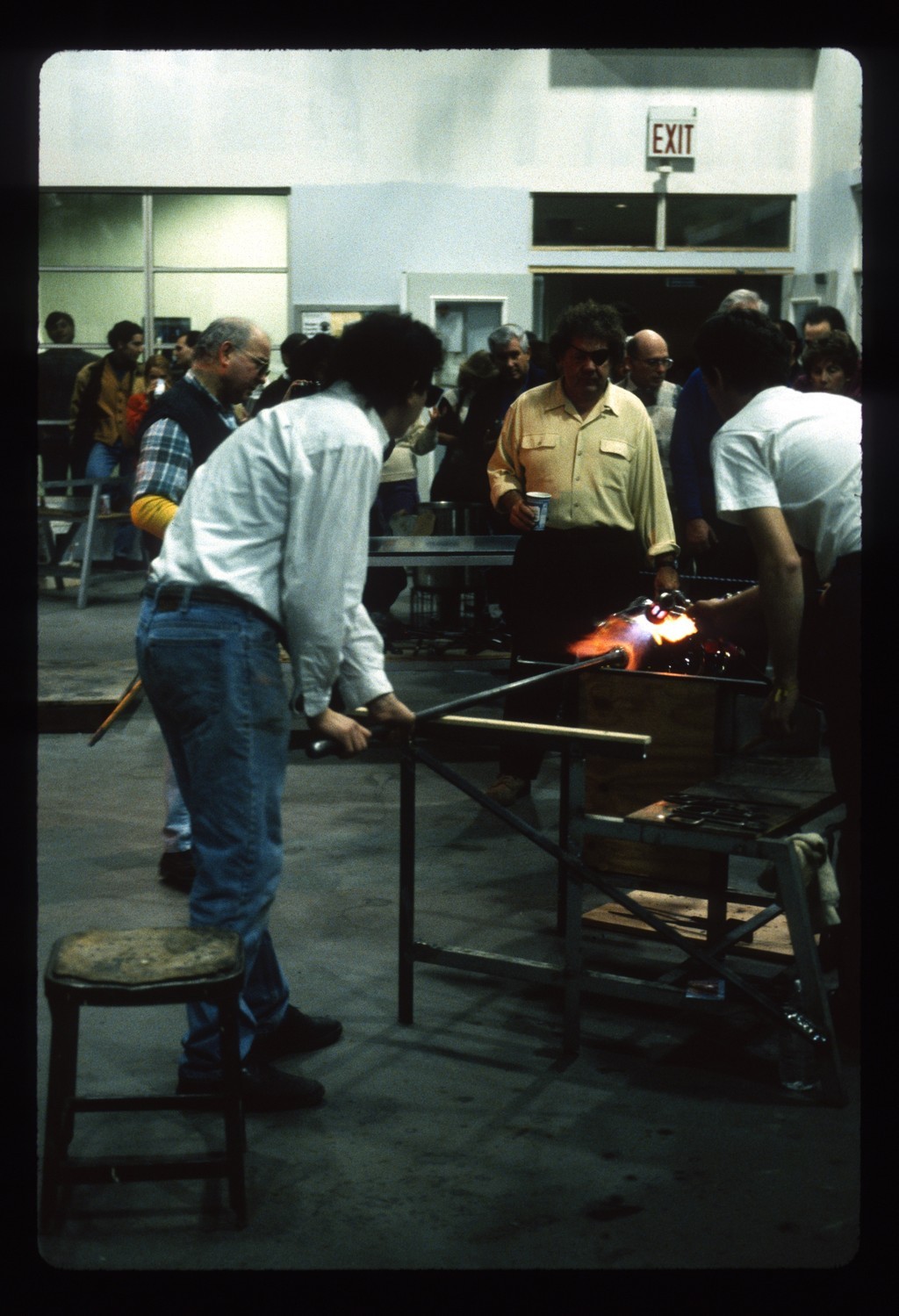

In 1992, not long after New York Experimental moved to Brooklyn, it hosted another workshop with Dale Chihuly. Chihuly was developing a new series of work, transitioning from his Macchia pieces into what he called the Venetians. These latest works were inspired by Venetian art deco glass and made in collaboration with the Italian glassblower Lino Tagliapietra. Tagliapietra joined Chihuly for the workshop and served as guest master gaffer. During the sessions, Chihuly started each piece by making a drawing that Tagliapietra then interpreted in glass with assistance from a full team, including Martin Blank (then Chihuly’s main gaffer), Robbie Miller, Joe Rossano, and others. As in 1985, assistants comprised both Chihuly’s team and volunteers from NYEGW, including James Harmon, Fred Kahl, and Karen LaMonte. Tagliapietra was highly respected for his skill and well known as one of the first Venetians to begin sharing Italian glassblowing secrets outside Italy, but few had seen him blow in person. His collaborative performance with Chihuly’s team was a significant event for NYEGW’s community and drew a big audience.

Dale Chihuly Venetian series piece made in 1990. Silvered Gold over Clear Venetian. Blown and silvered glass. Overall H: 31 in, W: 17 in, D: 17 in. Collection of the Chrysler Museum of Art (2011.12.1). Museum purchase with funds provided by Carolyn and Richard Barry, Jim Hixon, Oriana McKinnon, Leah and Richard Waitzer, Suzanne and Vince Mastracco, Doug and Pat Perry, Martha and Richard Glasser, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Lane Stokes, Jr., Cynthia and Stuart Katz in honor of Sidney L. Nusbaum II and in memory of Faith W. Nusbaum, Pat and Jeff Brown, Chrissy and Dave Johnson, Pat and Jack Stecker, and Sunny Williams. © Chihuly Studio. All rights reserved.

“Usually when Dale came to town there [were] multiple things going on.”

Richard Yelle discusses the 1992 Dale Chihuly/Lino Tagliapietra Venetian series demonstration at the Brooklyn location of NYEGW.

Martin Blank, Lino Tagliapietra, Fred Kahl, James Harmon, Jane Bruce, Geoff Isles, and Karen Chambers narrate the 1992 Dale Chihuly and Lino Tagliapeitra Venetian series workshop at New York Experimental Glass Workshop.

26:56 Transcript

Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra (at bench), New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“There’s sort of this value in having Lino do it–as this maestro making these pieces for Dale. It was a plus for both of them. Lino got a lot of publicity for doing these kind of things because it showed his wide range and abilities, and [it] also benefited Dale because it puts a true master glassblower on the end of these pieces, and certainly increased their value because of it.”

Lino Tagliapietra discusses Americans coming to understand the importance of technique in glassmaking.

01:11 Transcript

Robbie Miller (left, with cap), Fred Kahl (white t-shirt, background), Lino Tagliapietra (center), Martin Blank (right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dale Chihuly (in yellow) with James Harmon (left) and William Gudenrath (right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

James Harmon (left), Lino Tagliapietra (center) and Robbie Miller (right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Lino Tagliapietra (left), Martin Blank (foreground, long-sleeved white shirt), Dale Chihuly (yellow shirt) and Fred Kahl (right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“The coolest part is I remember being terrified the morning of the first morning, cause I’m the guy who had to turn pole for Lino [Tagliapietra.]. And my uncle had a little place in Greenwich Village, and I stayed on Thompson and Bleecker and—right in the Village, and I’d hop on a train and go in and blow glass. And it was great, great memories.”

Dale Chihuly (left), Lino Tagliapietra (center, with glass object), Martin Blank (right), Robber Miller (right background), Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“This is pretty, pretty epic.”

Martin Blank talks about teamwork and the ability to intuit what a glassblower needs in the Venetians demonstration.

01:13 TranscriptMartin Blank discusses working with Lino Tagliapietra during Chihuly’s 1992 Venetian series demonstration at NYEGW.

01:17 Transcript“It’s called the Venetians series. It started out as a collaboration where Dale would design them and Lino would make them. And eventually the Chihuly team picked up on it and would make them themselves but at this point in history, Lino made all of Dale’s Venetians series. And [Dale] did that with a couple of different artists, he did this other series with another huge Venetian artist, a glass artist named Pino Signoretto…And he did a whole series of works called the Putti series, which had more sculptural elements attached rather than this blown and feathered thing—so they had little angels attached to the bowls and things like that…So [Dale’s] employing Lino to do these things.”

Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Dale Chihuly Venetian series piece made in 1990. Cadmium Yellow-Orange Venetian made with Lino Tagliapietra and Richard Royal. Overall H: 49 cm, W: 36.2 cm, D: 41.7 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift with funds from Mr. and Mrs. James R. Houghton. (90.4.129).

“It’s visual. It’s visual, kinetic energy right there. Boom.”

Color used for Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Lino Tagliapietra at the bench, Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“I remember the first time [Lino] came to New York, I took him out to a sushi restaurant. And we had a great time and he said to me he said, ‘You know, everybody takes me to an Italian restaurant. You’re the first person that didn’t do that [laughs.]”

James Harmon (left, in brown), Robbie Miller (front, with cap), Fred Kahl (white t-shirt, background), Lino Tagliapietra (center, with glass), Martin Blank (background, white shirt), Karen Lamonte (right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“These are all really important folks.”

Dale Chihuly (left, in yellow), Martin Blank (center, white shirt), Fred Kahl (far right), Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Team member in aluminized suit with kevlar gloves preparing to grasp and transfer glass sculpture to annealing oven, Dale Chihuly Venetian series demonstration with Lino Tagliapietra, New York Experimental Glass Workshop (now UrbanGlass), Brooklyn, New York, 1992. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“The style of the object that we’re making is critical. And I know because I’ve been there with Lino for blow after blow. And I’ve been making Dale’s pieces forever. And I’ve also seen the foibles. I’ve seen the mistakes. I’ve watched the cracks. And so I’m cued in to how to make this experience survive—how to make the object survive its creation, which is the truth. There’s a high rate of failure in the creation and the birth of this piece.”

UrbanGlass: 21st Century

UrbanGlass, façade, Image courtesy of UbanGlass, Brooklyn, New York, Photo: Mert Erdem and Michael Wilson.

UrbanGlass has thrived in Brooklyn. In 2013, the organization completed a full-scale, two-year renovation, resulting in a 17,000-square-foot studio space with six glory holes and the new Agnes Varis Art Center on the first floor, containing an exhibition gallery and a retail store. In addition to a hot shop, UrbanGlass now has a cold shop, kiln room, mold room, and rooms for flameworking and flat glass. The organization has continued to welcome and exhibit artists working in a variety of media. Artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Matthew Barney, Kiki Smith, and designer/architect Maya Lin have produced pieces at the facility. Art students from Parsons and NYU still take classes at UrbanGlass, as do students from Pratt Institute, the School of Visual Arts, and Brooklyn College. Since 1997, UrbanGlass has run the Bead Project, a scholarship program in glass beadmaking that helps women in financial need learn a profitable skill.

Robert Rauschenberg, Tire, made with the assistance of Dan Dailey and Daniel Spitzer at UrbanGlass Studio, designed in 1995-1996 and made in 2005. Overall H: 78.7 cm, W: 68.5 cm, D: 29.2 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift in part of Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and The Greenberg Foundation, and the F. M. Kirby Foundation, © Robert Rauschenberg.(2007.4.5).

“We were approached about making those tires. John Perreault was the director. And, I was on the board of directors, but I was extremely fascinated with the whole idea of trying to make a full tire out of cast glass and the truly amazing thing in my opinion was that they were really nice. I mean, I was surprised how well they came out. The part of the story that I like is that Rauschenberg Studio did not offer to pay us. They offered us one of the tires. And we were all ecstatic, and it was a nice one, but then it turned out to be a problem for us because it was a valuable piece of sculpture, and we had to insure it and we had to store it and…eventually it went to The Corning Museum, and it can be seen there today. But they made three or four of them, of course, because in cast glass, you never know what’s going to happen for sure.”

Bead Project Graduates celebrate at the 2019 graduation ceremony. Image courtesy of UbanGlass, Brooklyn, New York.

“I think there is kind of some elitism in glass, and there was less of it at UrbanGlass and New York Experimental. And that’s part of what makes it unusual. And, you know, the fact that there’s this [program] that UrbanGlass calls the Bead Project, which is taking women who might be in a marginalized situation, and not only giving them a skill, but giving them something that really they’ve been able to thrive with. I mean, the Bead Project has been a huge success. And it’s a very uniquely urban possibility. Having it there has been healthy for the UrbanGlass community. That’s part of what is unique and good about the glass environment at UrbanGlass.”

Cybele Maylone discusses UrbanGlass’s Brooklyn facilities.

“I think it’s really important that artists making work in glass are not only making work in glass, and so we’ve really tried to keep an open mind as to our exhibition programming in giving a broad perspective into the way that artists work.”

Andrew Page talks about the economic challenges New York Experimental Glass Workshop/UrbanGlass has faced during its history.

01:31 Transcript