Pilchuck Glass School

Stanwood, Washington

Pilchuck Campus, by Stephen Vest, © Pilchuck Glass School.

Introduction

Pilchuck opened near Stanwood, Washington in 1971. Dale Chihuly, inspired by his summertime teaching experience at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in the remote woods of Deer Isle, Maine, envisioned a similar summer school in the forests of his native Washington State, but one devoted entirely to glass. In the spring of 1971, Chihuly, then a young faculty member at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and Ruth Tamura, director of the glass program at the California College of Art and Design (later California College of the Arts), received a grant from the Union of Independent Colleges of Art (UICA) to start a summer glass workshop. Haystack board member and weaver Jack Lenor Larsen suggested that Chihuly contact art patrons John H. and Anne Gould Hauberg about a site for the workshop. The Haubergs, who owned a large tree farm about fifty miles north of Seattle, invited the workshop to use the property, and Pilchuck ultimately settled there with the Haubergs’ support. Pilchuck’s focus on a single medium, glass, set it apart from other well-known residential craft schools. It quickly became an important center for glass education, attracting a long list of studio glass artists as students and teachers. Pilchuck has no standing faculty; glass artists travel from all over the world to teach, assist, and learn there.

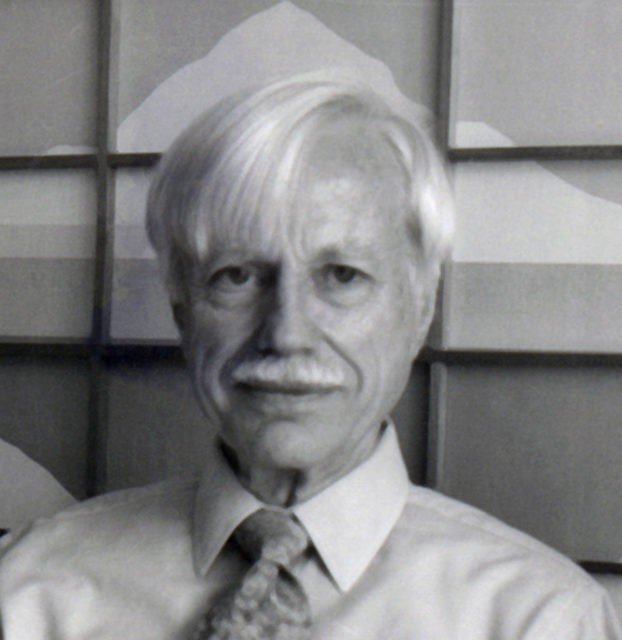

This section outlines Pilchuck’s early history. It recounts how students and teachers created the campus from the ground up in the first decade; discusses Chihuly’s changing role; tells how the school fostered artistic exchange, including exchange across artistic media within the U.S. and internationally, and how it helped anchor the development of glassworking in the Pacific Northwest. In addition, the section features interviews and correspondence with James Carpenter, Paul DeSomma, Kate Elliott, Michael Glancy, Ferd Hampson, William Morris, Jay Musler, Andrew Page, Flo Perkins, Mary Shaffer, and Toots Zynsky conducted between 2016 and 2021. It also includes excerpts from 1982 interviews by Paul Hollister with William Carlson, Joey Kirkpatrick, and Klaus Moje; a transcript of a 1984 interview with Moje; transcripts of 1984 audio recordings made for Hollister by Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace and by Jay Musler; and a recording by Dan Dailey, c.1989–90. Hollister’s research and publications about Pilchuck-affiliated American and international artists are highlighted throughout.

Toots Zynsky characterizes Pilchuck as “a center for learning every possible type of glassmaking in the world.”

00:57 Transcript

Making Pilchuck

In 1971, Pilchuck’s inaugural group of students and teachers came from across the United States. As a condition of Pilchuck’s founding grant from the UICA, each of the consortium’s eight art schools—Dale Chihuly’s and Ruth Tamura’s home institutions among them—were invited to send two students free of charge. Chihuly’s RISD students included Toots Zynsky; James Carpenter, John Landon, and Robert Hendrickson served as instructors. Tamura brought students from the California College of Art and Design, in Oakland. William Carlson attended from the Cleveland Institute of Art. Pilchuck was an empty field that first summer. Students and faculty camped in tents in the Pacific Northwest rain, ate meals at a communal table, and set about building a temporary hot shop, which would take the form of a tree pole structure with a sewn-together tarp roof, two furnaces, and an annealing oven. Although glass was made, the early years at Pilchuck were more about community building than blowing lasting objects. It would take several years for the school to become a center of glass creation.

Further Reading: Tina Oldknow, Pilchuck: A Glass School (Seattle: Pilchuck Glass School in association with the University of Washington Press, 1996).

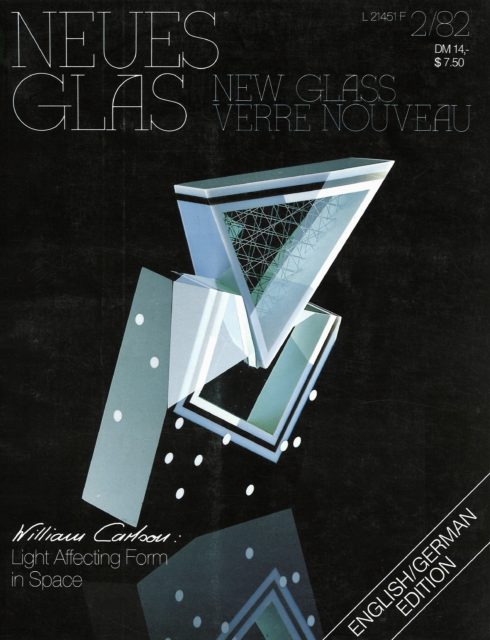

In this 1982 interviewer with Paul Hollister, William Carlson speaks about his use of core drilling and its place in his overall design strategy, questions his use of millefiori as embellishment, and discusses how the “very rigid design definition” in his pieces differs from the open-ended forms in Dale Chihuly’s work.

“Light Affecting Form in Space: Glas von William Carlson / William Carlson’s Glasswork.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 84–88.

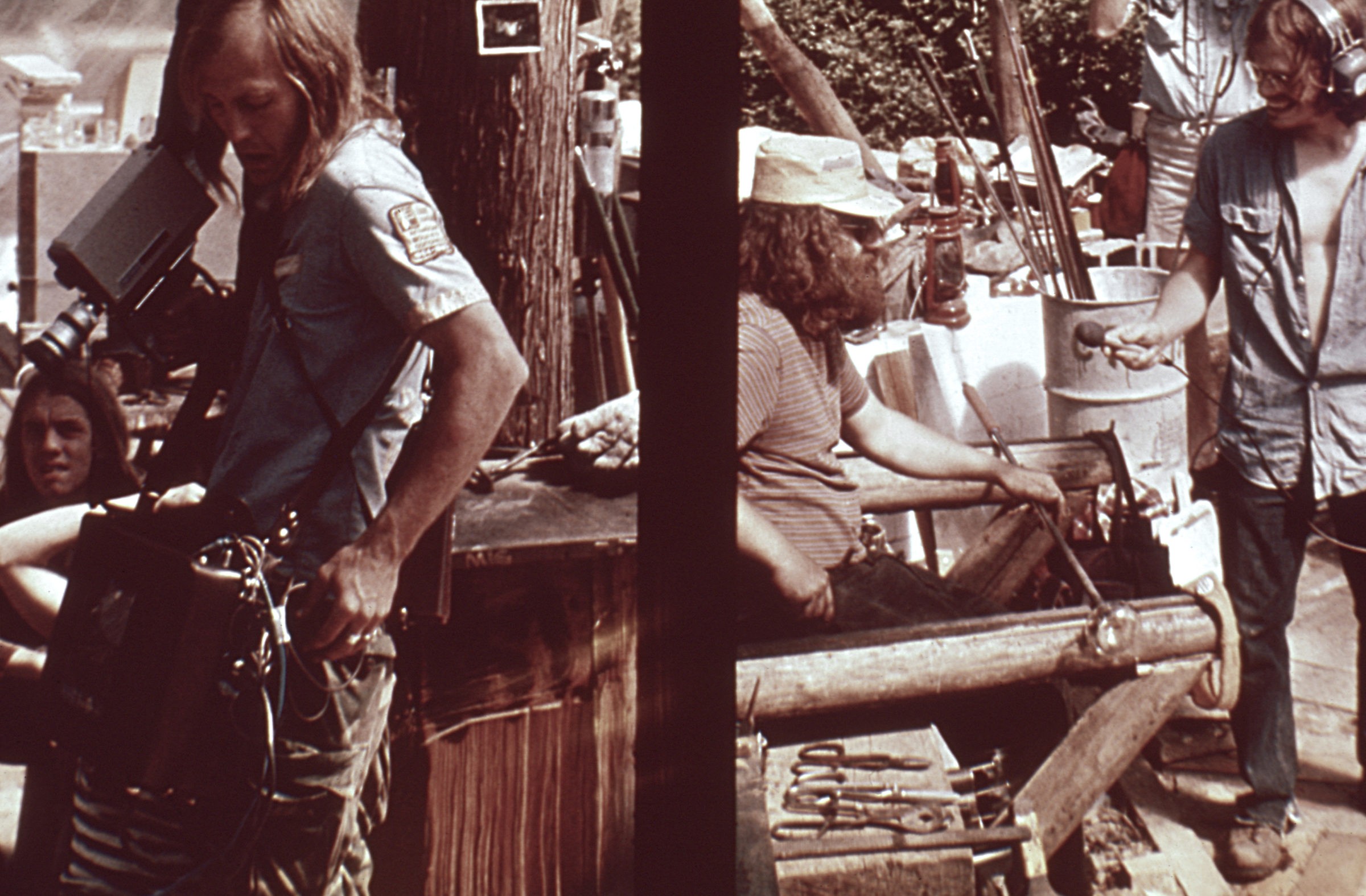

First hot shop, 1971. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

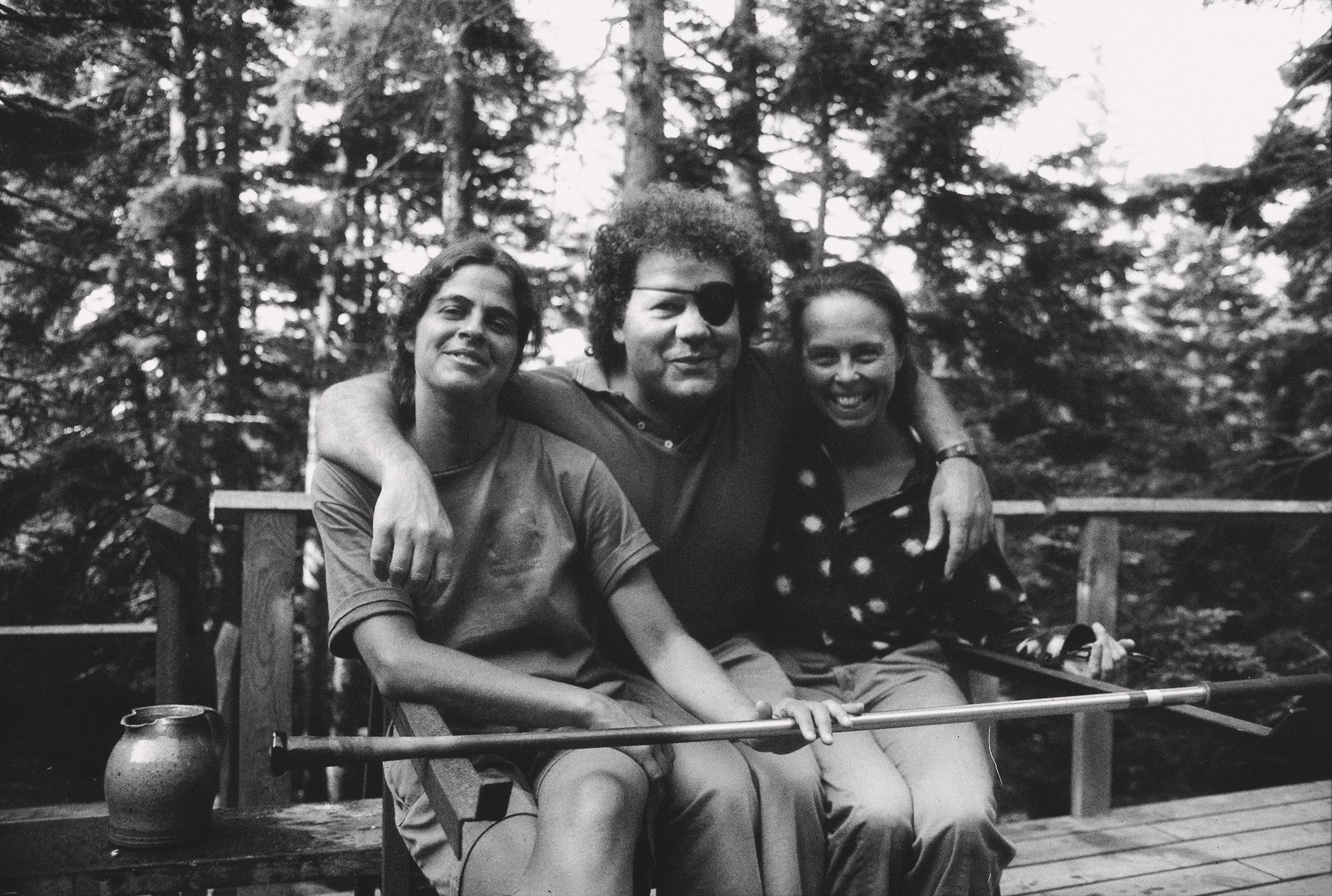

John Landon’s tipi with Debbie Goldenthal (left) and Toots Zynsky, 1971. Image courtesy of Toots Zynsky.

Michael Glancy talks about Dale Chihuly and the crossover between RISD and Pilchuck.

01:49 Transcript

Experimentation

Although Pilchuck eventually focused exclusively on glass, it offered instruction in a range of media in its earliest days. For instance, Buster Simpson, an artist working in video, was a core faculty member when photography, video, and audio were course options. Toots Zynsky was among the artists who experimented with other media in collaboration with Simpson, creating a performance work in which she used contact microphones to record the sound of glass shattering. Even though Chihuly split with Simpson in 1973 and deliberately moved Pilchuck in a glass-only direction, other artists continued working with Simpson after he left the fold. Among them was James Carpenter, who in 1975 enlisted Simpson’s assistance in making a film on salmon migration for an installation piece.

Audio and video recording of Fritz Dreisbach blowing glass (Buster Simpson, left), 1972. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

“I went to Pilchuck that summer [1974]. Dale was teaching, Jamie Carpenter was teaching, and the other teacher was Fritz Dreisbach. And Fritz was pretty wild and loose with the hot glass, and it was great. And that was the turn-on for me. How loose Fritz was with it. And Jamie and Dale were doing interesting stuff, and this is post-neon and hot glass blocks. And—oh, they were doing the RISD ring vase pieces, and it was just in the beginning of people figuring out, learning how to work together like the Italians. So that was interesting.”

Toots Zynsky discusses early multimedia offerings at Pilchuck.

0:29

Toots Zynsky working on Time/Release video project, with artist Duan Hall assisting, 1973. Image courtesy of Toots Zynsky.

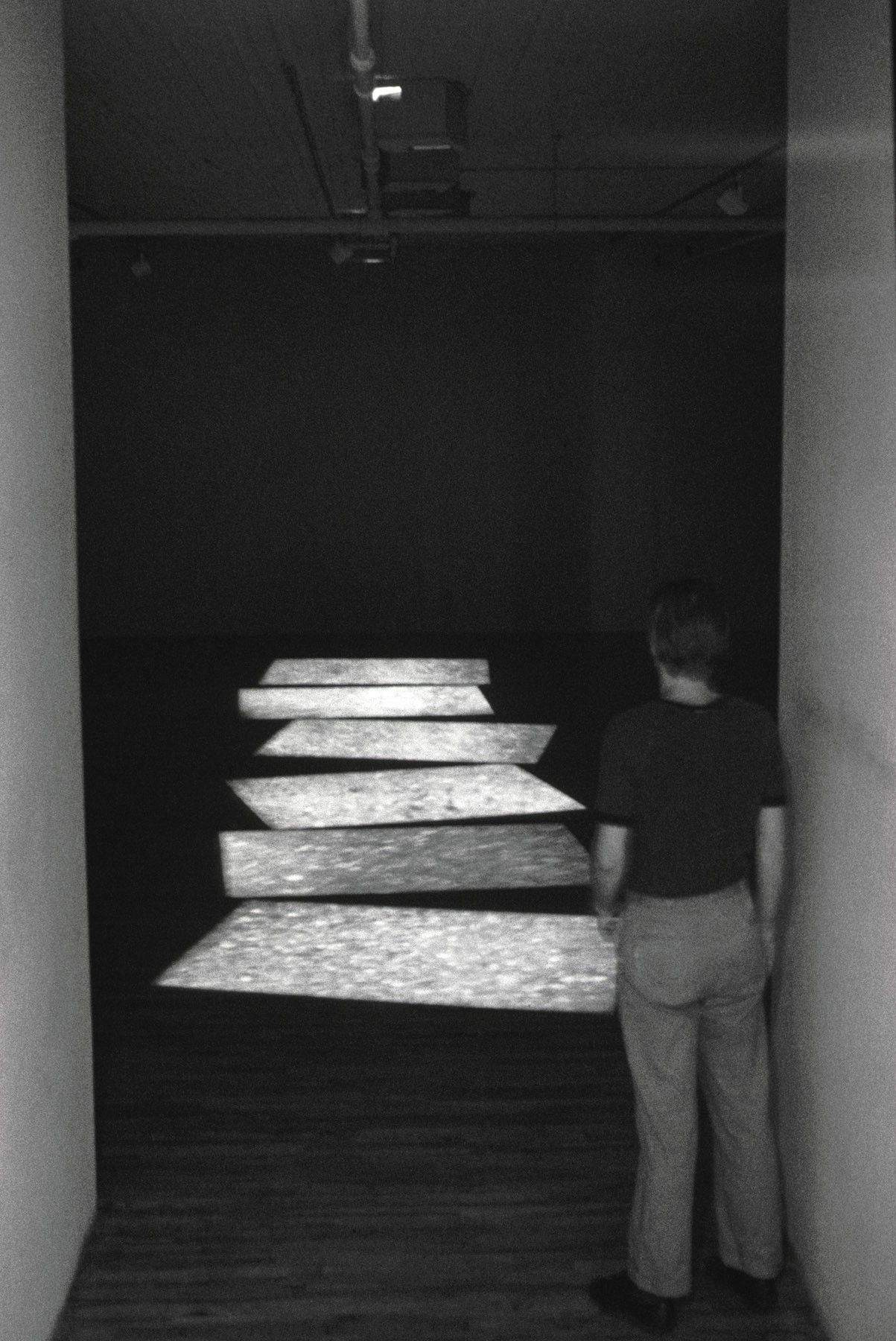

James Carpenter, Migration, filmed in 1975 (camera work by Buster Simpson). Installation view. Image courtesy of James Carpenter Design Associates (JCDA). Photo: Dan Reiser.

Flo Perkins discusses a letter she got from Dale Chihuly encouraging her to come to Pilchuck.

00:21 TranscriptFlo Perkins talks about taking her bicycle on a train across Canada to meet Dale Chihuly.

00:20 TranscriptPlacemaking

During Pilchuck’s first few years, work often went beyond making glass to making the place itself. The first summer, while most people camped, John Landon built a housing structure—a “Sioux-style” tipi. In 1972, the second summer, Pilchuck’s “campus” had nearly fifty residents, and many set about creating their own dwellings from such items as discarded window frames and doors and thrift shop materials. Several homes, including instructor Buster Simpson’s, incorporated tree stumps into their structures. Artist Therman Statom made his version of a yurt. James Carpenter and Dutch artist Barbara Vaessen created a delicate, all-glass structure with stained-glass windows made by Vaessen. Many homes were re-used and remodeled, but by 1974 students were no longer allowed to build their own abodes, and by 1977 a large percentage of them had been torn down. However, in 1981 instructors Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick were given special permission to build their own home on the Pilchuck site. The structure is still used by the school. In 1995 artist Hank Murta Adams, with the help of students, built Trojan Horse, a tribute to Pilchuck’s early artist-built homes.

Buster Simpson’s Stump House, 1972. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

James Carpenter and Barbara Vaessen’s house, 1973. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

Shelter by Dan Holmes, 1972. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

“I convinced my father that it was a good idea for me to go there so I took the train from Chicago in June 1972….I was there all ten weeks basically living under a plastic bag held up by sticks to stay dry. I remember only about one or two weeks of sunshine that summer. It was a muddy mess of building the glass shop and moving the furnaces and cooking and occasionally being able to blow glass.”

Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick building their Pilchuck home, 1981. Image courtesy of Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick.

Flora Mace in the Pilchuck home she and Joey Kirkpatrick were building, 1981. Image courtesy of Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick.

Hank Murta Adams with his Trojan Horse, 1995. Image courtesy of Hank Murta Adams.

Detail of Hank Murta Adams’ Trojan Horse, undated. Image courtesy of Hank Murta Adams.

Pilchuck’s Changing Campus

Over time, Pilchuck gradually replaced its makeshift infrastructure with permanent facilities. The hot shop that had been painstakingly built by students and faculty during the school’s first summer had to be rebuilt the following year. However, more lasting facilities were needed. John Hauberg asked architect Thomas Bosworth, who was involved with Pilchuck and later became the school’s director, to design a hot shop. The resulting rustic log structure, completed in the summer of 1973, was the first of seventeen buildings Bosworth designed for the campus. Several, including the hot shop, won architecture awards, and all were made of exposed timbers that blended in with the surrounding landscape. A flat shop for stained glass and other projects was built in 1976, and a large-scale lodge for lectures and community dining—a longstanding Pilchuck tradition—was completed a year later. Although Bosworth added faculty cottages and a bathhouse in 1977, the first official student residences (two small cottages) were not built until 1980. Between 1974 and that time, student accommodations were limited to tents on a platform. Pilchuck later included an artists-in-residence studio and full-scale dorm, built in 1983 and 1984, respectively. A cold shop and studio building were added in 1986.

Campus housing, upper cottages, designed by Thomas Bosworth and built in 1979. Pilchuck Glass School, 2018, © Pilchuck Glass School.

Staff housing, designed by Weinstein Copeland Architects, built beginning in 1998. Pilchuck Glass School, 2018, © Pilchuck Glass School.

Artist Networks

Pilchuck has interconnected educators, students, and makers regionally, nationally, and internationally. Their roles have overlapped at the school, which has continued to operate on Chihuly’s founding philosophy of “artists teaching artists.” Independent professional artists, tenured academics, and graduate students have served as faculty and mentors at Pilchuck, where they have been able to use the facilities to make their own work with the help of teaching assistants. Conversely, full-fledged professional artists have often enrolled as students to learn from their peers and expand their skills.

Dale Chihuly conversing with Pilchuck instructors and students, pictured clockwise from center foreground: Peter Larsen (plaid long-sleeved shirt), Phil Hastings (glasses), Parran Sledge (background, behind Hastings), James Carpenter, Chihuly, Kate Elliott (behind dog), Debbie Goldenthal, Elaine Hyde (blonde hair), Kerry Marshall (far right), Robin Orcutt (right foreground), 1972. Image courtesy of Kate Elliott. Photo: Bruce Bartoo.

Teaching

Well-known glass artists from the United States and abroad have taught at Pilchuck. Early instructors were often friends of Chihuly’s. Among them were Italo Scanga, an Italian sculptor on the RISD faculty, and Fritz Dreisbach, who taught for six consecutive summers in the school’s formative years. Dreisbach continued to teach off and on after that, and later was a Pilchuck trustee. Many other instructors also returned repeatedly. Studio glass artists who frequently taught at Pilchuck include Sonja Blomdahl, Dan Dailey, Michael Glancy, Henry Halem, Joey Kirkpatrick, Walter Lieberman, Flora Mace, Richard Marquis, Benjamin Moore, William Morris, Richard Royal, Therman Statom, Dick Weiss, and Ann Wolff. Pilchuck embraced the collaborative team approach often found in European glass factories, with the resut that teaching assistants—gaffers who help execute instructors’ and students’ ideas—have played an important role at the school.

As class sessions and techniques were added, the roster of teachers grew. While hot glass had always been the school’s focus, warm glass techniques—including fusing, slumping, and sand casting—and cold processes such as engraving and stained glass making, also were popular. Ginny Ruffner was a long-time teacher of flameworking, and Narcissus Quagliata, Susan Stinsmuehlen-Amend, Catherine “Cappy” Thompson, and Pike Powers were well known for their work in the flat shop. Some students and teachers later joined Pilchuck’s staff. Kate Elliott, an early Pilchuck student, eventually served as Chihuly’s professional assistant and taught classes with him at both RISD and Pilchuck. Powers was Pilchuck’s artistic director from 1993 to 2007.

Kate Elliott in back of a car at Pilchuck, 1972. Image courtesy of Kate Elliott. Photo: Bruce Bartoo.

“Kate Elliott was important because later, when she opened Elliott Brown Gallery in Seattle, it was the best gallery on the scene. It was small and thoughtful, rather than big and splashy and giving discounts all over the place. Kate never asked me to “split the discount” or any other expenses for that matter. Her business ethics were excellent in my experience, her taste was impeccable, and her understanding of everyone was thorough, of artists, historians, and collectors alike. It was a wonderful time. Kate has always been a great supporter of Dale and has done many, many kind and responsible things for and with him regarding his career, many of them in the wings. I have plenty of respect for Kate.”

Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace with Italo Scanga at Pilchuck, 1985. Image courtesy of Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace.

Joey Kirkpatrick (left) and Susan Stinsmuehlen (later Stinsmuehlen-Amend) at Pilchuck, 1982. Photo: Henry Halem.

Michael Glancy (left) with Paul Marioni, 1979. Image courtesy of the Glancy Family.

Michael Glancy, Maelstrom, made at Pilchuck Glass School, 1981. H: 13.3 cm, D: 18.5 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of the Chodorkoff Collection. (85.4.93).

Robert Carlson, Der Temple von Adam und Eva (Adam and Eve’s Temple), 1986, made at Pilchuck Glass School. Overall H: 64.5 cm, Diam (max): 24 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift of Raymond E. Fontaine. (86.4.202).

Catherine “Cappy” Thompson, The Virgin and the Unicorn, made at Pilchuck Glass School with the assistance of William Morris, 1988. Overall H: 43.1 cm, Diam (max): 36.2 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (90.4.131).

International Exchange

U.S. and European artists have encountered one another at Pilchuck to their mutual benefit, making it an important center of artistic interchange. Americans with experience working in glass abroad have come to the school as students and teachers. They include James Carpenter, Dan Dailey, Marvin Lipofsky, and Richard Marquis, all of whom had spent time in Venetian glass factories. Numerous international artists have taught at Pilchuck, beginning with Erwin Eisch of Germany during the school’s second summer. Among many others, Klaus Moje and Isgard Moje-Wohlgemuth came from Germany; Jaroslava Brychtová, Jiří Harcuba, and Stanislav Libensky from the former Czechoslovakia; Jan-Erik Ritzman, Bertil Vallien, and Ulrica Hudman-Vallien from Sweden; and Checco Ongaro and his brother-in-law, Lino Tagliapietra, from Italy. Just as European makers modeled long-established glass techniques and materials that were often grounded in factory systems, so too they observed how freely American artists worked outside such traditions. Some, like Tagliapietra, who in 1980 was one of Pilchuck’s earliest official artists-in-residence, eventually chose to leave their employment at glass firms and start their own studios as independent artists.

Toots Zynsky discusses Pilchuck connecting people from other regions and cultures.

0:58

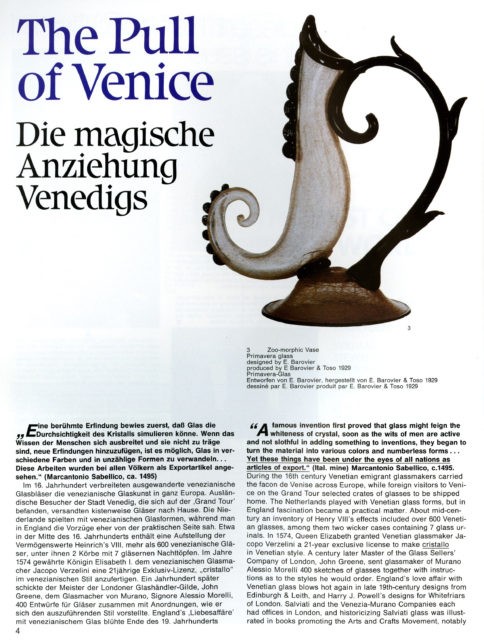

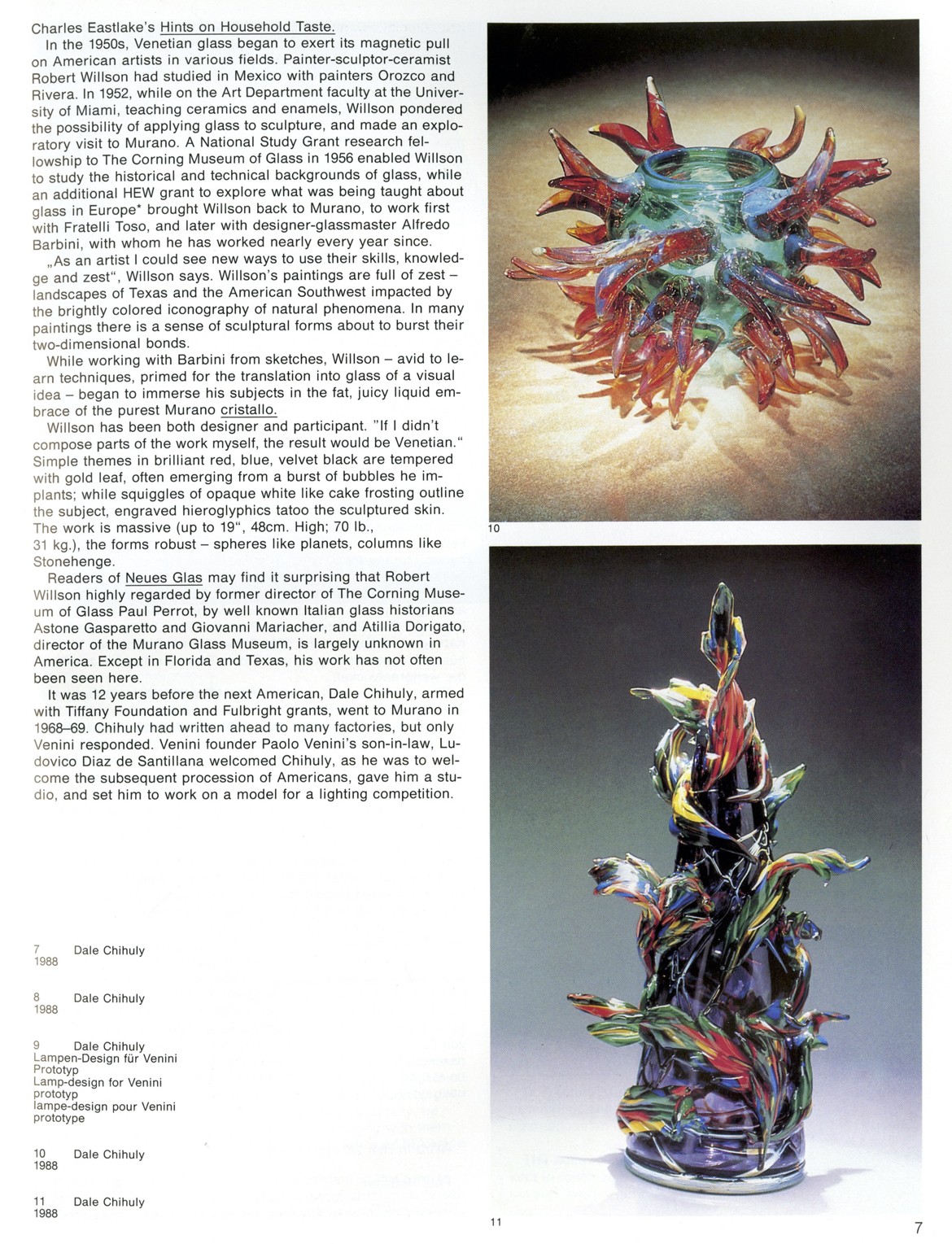

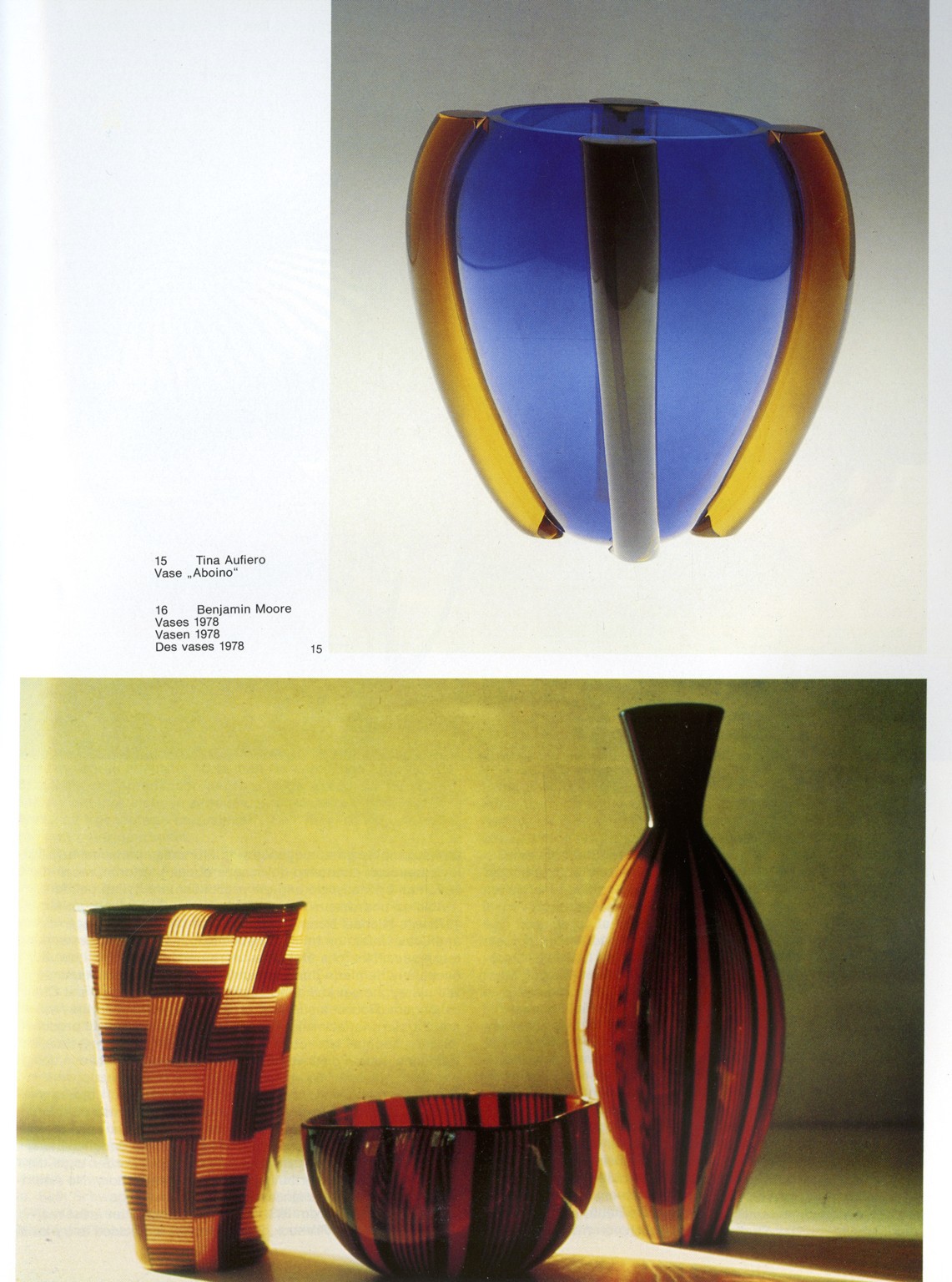

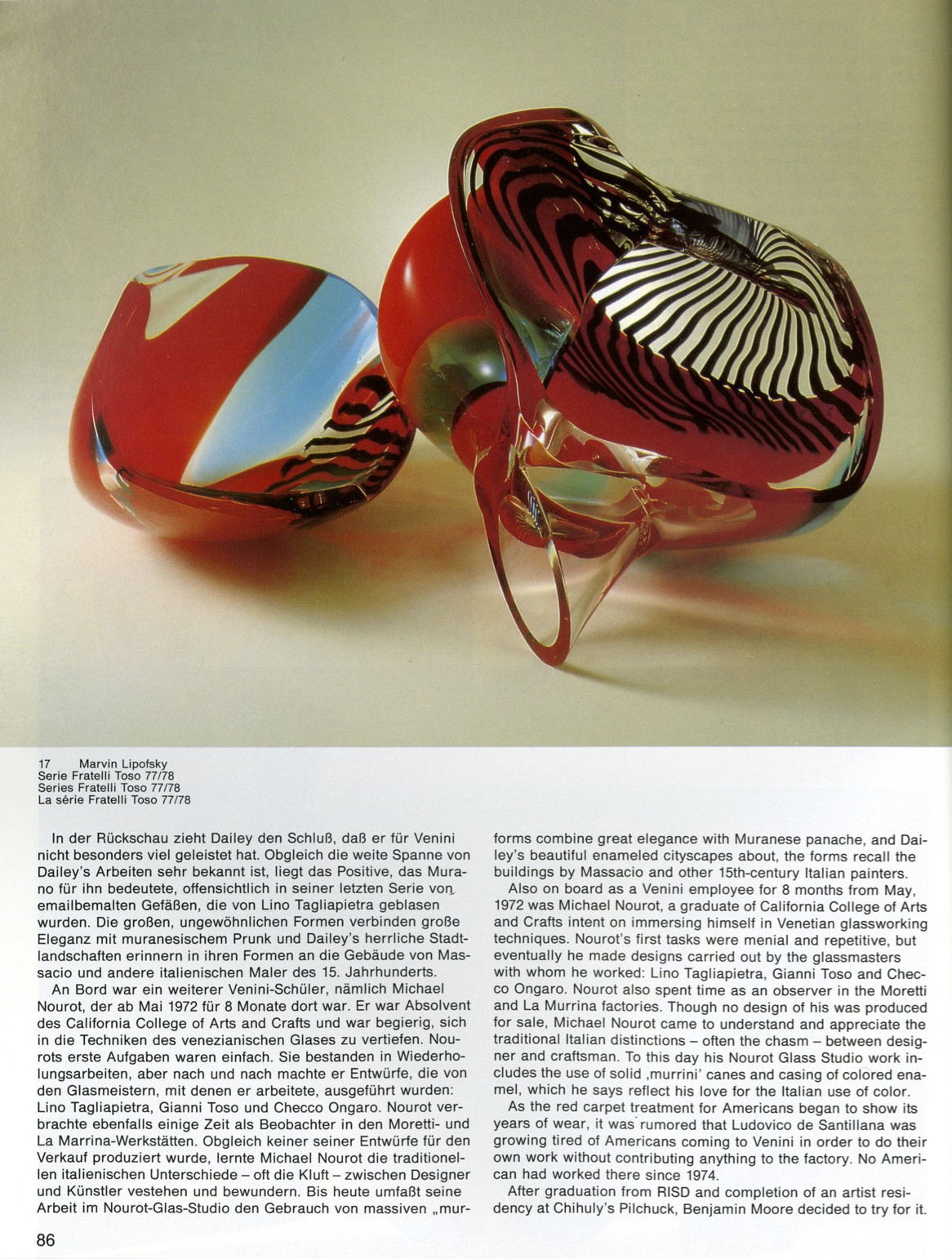

“Die magische Anziehung Venedigs / The Pull of Venice.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1990): 4–9.

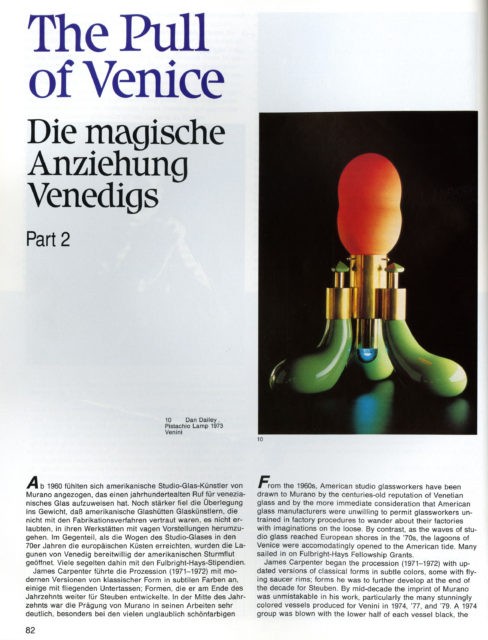

“Die magische Anziehung Venedigs / The Pull of Venice: Part 2.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1990): 82–88.

“International Artists Exhibit Their Glass.” New York Times, November 8, 1979, C3.

Permalink: https://nyti.ms/2EgSsV7

Paul Hollister, “The Pull of Venice/Die magische Anziehung Venedigs,” Neues Glas, no. 1 (1990): p. 7.

Paul Hollister, “The Pull of Venice/Die magische Anziehung Venedigs: Part 2,” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1990): p. 85.

Paul Hollister, “The Pull of Venice/Die magische Anziehung Venedigs: Part 2,” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1990): p. 86.

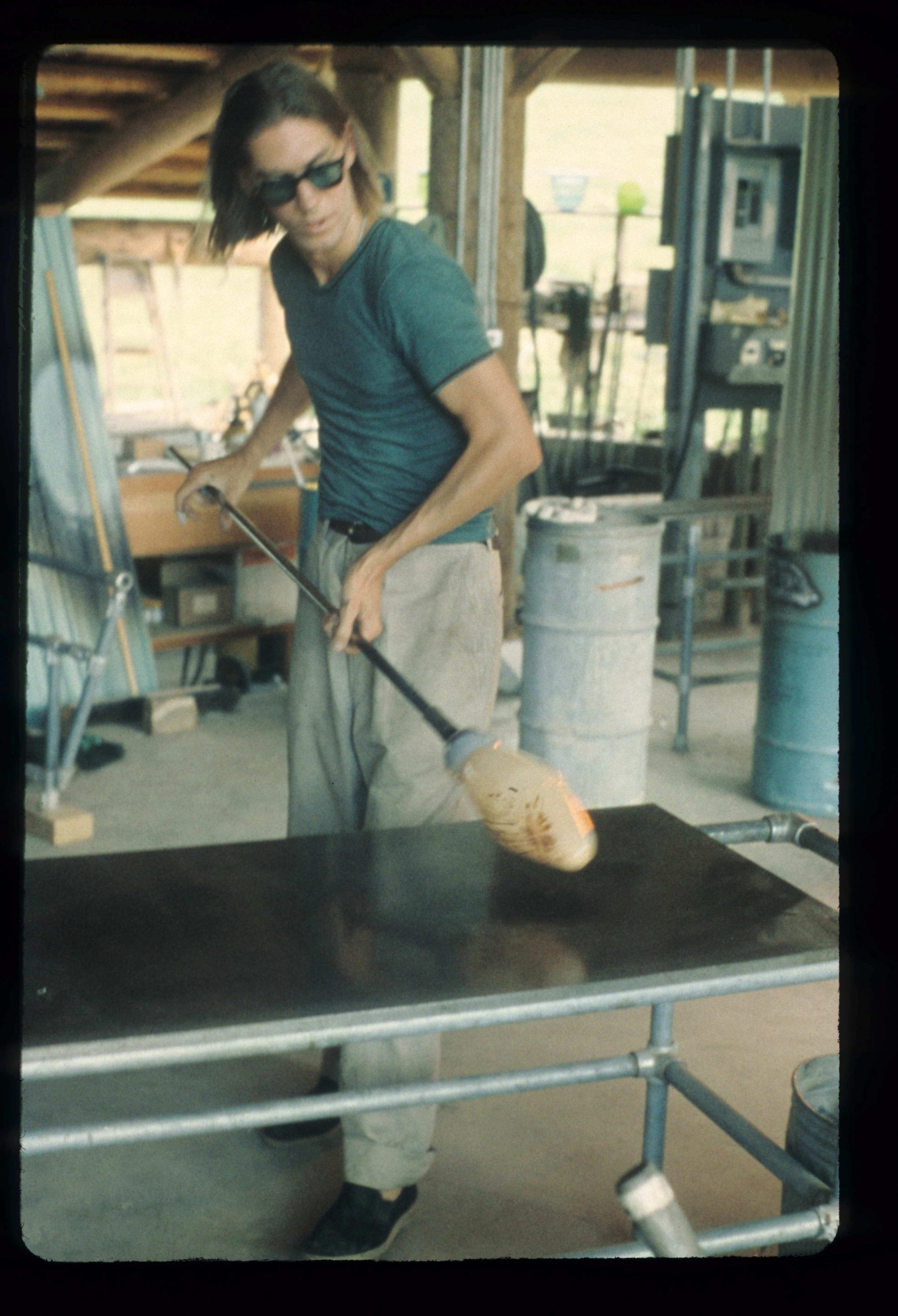

James Carpenter at the marving table, Pilchuck Glass School, 1974. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

James Carpenter vessels at Pilchuck, 1974. Image courtesy of Pilchuck Glass School.

“But when I was at Venini I sort of befriended one of the masters, this guy named Mario Grosso. I just sort of sat with him literally all day long and sort of watched. And at lunchtime I would do a little something and sort of help or one of the other guys would help or something, so I just sort of really tried to learn how to make glass. You know, not having done that. I mean Dale and I were just doing something totally different. Cause really I just learned how you could do more with it. And so I sort of focused on that for the year, just learning about making glass and then when I came back to Pilchuck, yes, that’s where we brought back working on the marving tables and all that stuff.”

Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtová, Family Eye, made at Pilchuck Glass School with the assistance of Benjamin Moore, Richard Royal, Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick, 1982. Overall H: 20.5 cm, W: 28.8 cm, D: 25.2 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Gift in part of Peter and Margarete Harnisch (2001.4.22).

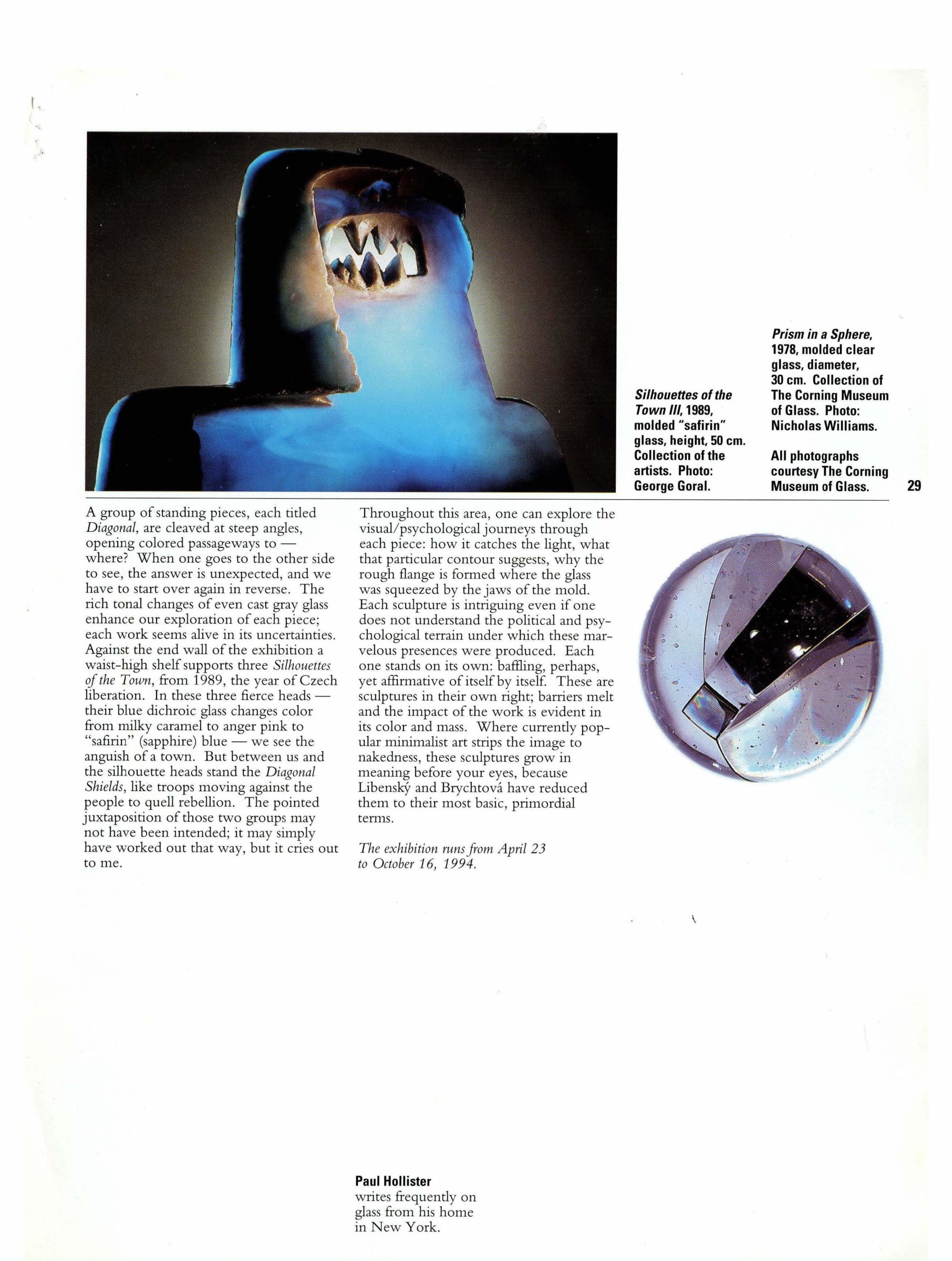

“Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová.” Glass, no. 56 (Summer 1994): 24–29.

Paul Hollister, Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtová,” Glass, no. 56 (Summer 1994): p. 25.

Paul Hollister, Stanislav Libensky and Jaroslava Brychtová,” Glass, no. 56 (Summer 1994): p. 29.

“in the early days, I mean, we would have spent a lot of time trying to reinvent a wheel that had already been invented, if it hadn’t have been for those people going over, bringing back techniques, information, methodology from…Europe.”

From left: Lino Tagliapietra, Ben Moore, and Martin Blank at Chihuly Studio, Seattle, Washington, 1988. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (CMGL 151356) © Marvin Lipofsky.

“So Lino [Tagliapietra] went out there two or three times to Seattle and was also invited back to Pilchuck again and again. And he started to have a new routine…and he would make things. And gradually he started to focus on making works of his own that were his own designs that come—to me—pretty directly from the years and years of observation of the way the material behaves and the processes lead to form, and, you know, the way he wanted to kind of bring that into something that was his own, which is unusual compared to the normal path of those guys who are in such a tight community.”

Dan Dailey discusses Lino Tagliapietra severing ties with the Murano glass community in a recording for Paul Hollister (c. 1989-1990).

03:13 Transcript

Michael Glancy discusses how Lino Tagliapietra felt the glass tradition in Murano was dying.

00:58 TranscriptInviting Artists

Chihuly was adamant that Pilchuck stay focused on glass despite pressure from the board of trustees to add other media. At the same time, he consistently encouraged the school to bring in artists who were not known for working in glass. Chihuly’s own practice had successfully crossed over into the world of fine art, and over time a number of artists not primarily associated with glass were invited to spend time at Pilchuck. While some were teachers, many were artists-in-residence, such as Nicholas Africano, Judy Pfaff, Jacob Lawrence, Donald Lipski, William T. Wiley, Christopher Wilmarth, Nancy Graves, Ann Hamilton, Jana Serbak, and Willie Cole. Several artists who worked at Pilchuck also made pieces at New York Experimental Glass Workshop (later UrbanGlass). They included Lynda Benglis, Dennis Oppenheim, Kiki Smith, and architect/designer Maya Lin.

Artist-in-residence Christopher Wilmarth (left) with Joey Kirkpatrick as gaffer, 1983. Image courtesy of Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace.

“The whole idea of the artist-in-residence program was to bring in artists who had careers in what was considered the fine arts and introduce them to glass.”

Paul Hollister at Pilchuck

Dale Chihuly and William Morris at Pilchuck, 1980. Photo: Dick Busher.

William Morris, Shard Vessel, made at Pilchuck Glass School, 1980. Overall H: 26.1 cm, W: 17.7 cm, D: 18.4 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (2006.4.173).

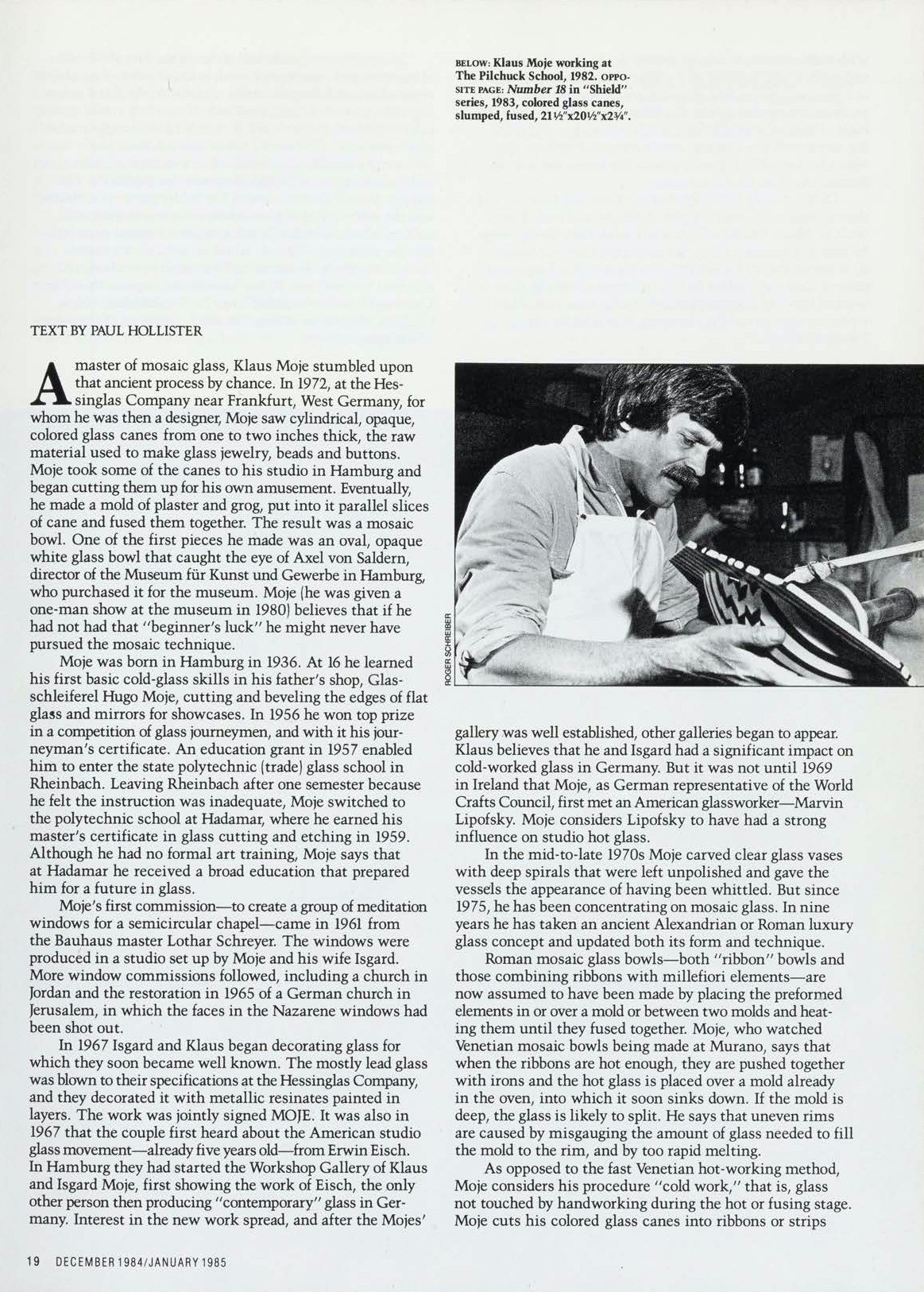

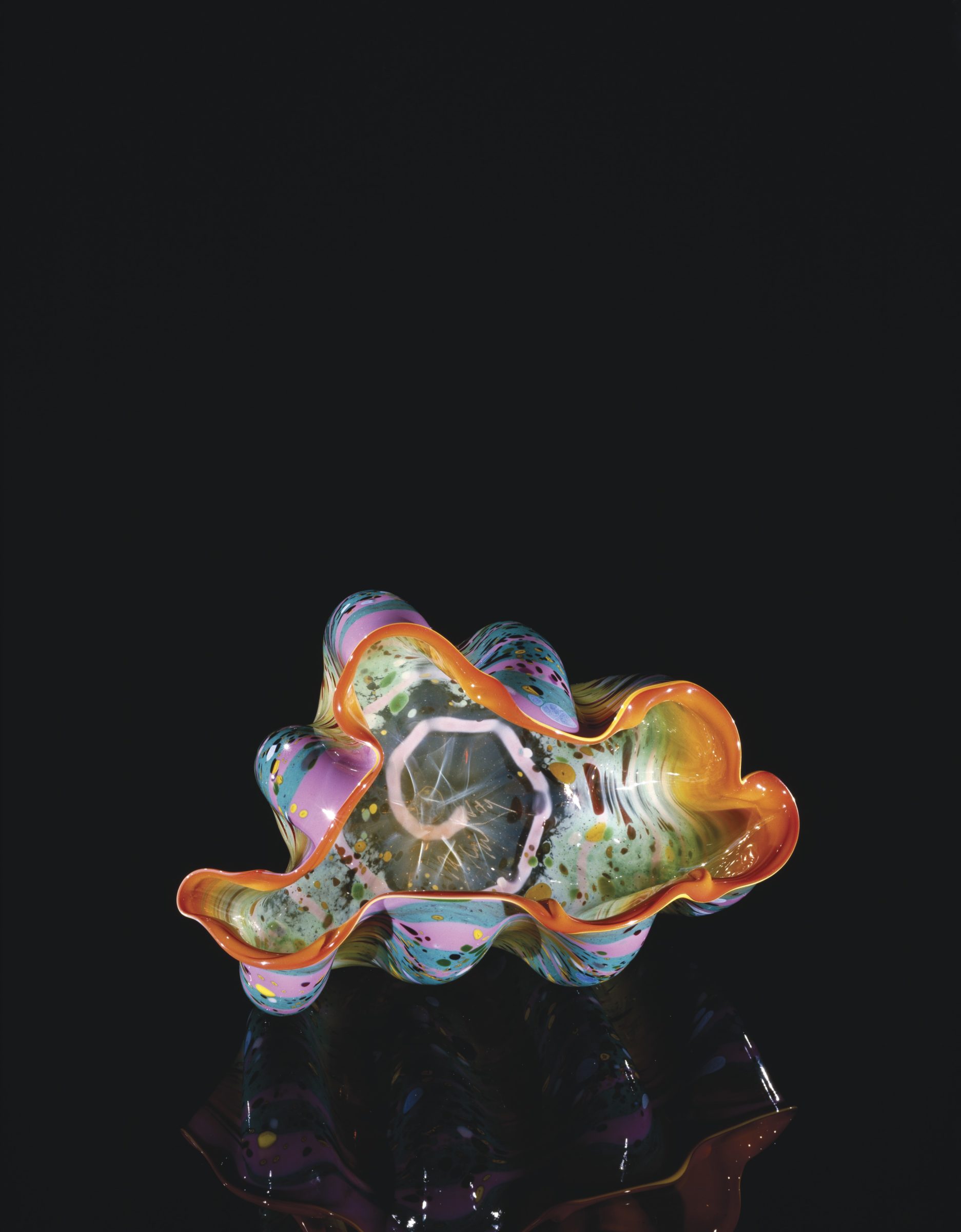

Paul Hollister went to Pilchuck in 1982 to give a lecture and took the opportunity to talk to a number of artists there. He conducted interviews with Klaus Moje and Joey Kirkpatrick (discussing her collaborative work with Flora Mace) and later wrote feature articles about all three. He recorded Dale Chihuly’s Macchia Series glassblowing demonstration at Pilchuck, which he witnessed again at New York Experimental Glass Workshop (later UrbanGlass) in 1983 and 1985.

The 1980s were a transitional time for Pilchuck. At the start of the decade, Chihuly resigned from his post at RISD, and Alice Rooney became Pilchuck’s director. Chihuly, together with Mace and Kirkpatrick, started Pilchuck’s artist-in-residence program, which eventually welcomed a wide variety of artists from across the country. In 1981, Mace and Kirkpatrick became the first women at Pilchuck to teach glassblowing. Benjamin Moore, Chihuly’s former gaffer, and William Morris, then Chihuly’s chief blower, both held positions in the hot shop. Moore was also Pilchuck’s education director for many years. By 1983, Moore, Morris, Mace, and Kirkpatrick all participated in selecting the school’s faculty, and in 1984 Pilchuck formed its International Council to bring students from abroad. Paul DeSomma joined Pilchuck’s staff in 1986 and worked his way through several roles in the hot shop. Moore left Pilchuck in 1987 after a thirteen-year tenure. However, in 1991 he was among the first artists—along with Moore and Kirkpatrick—invited to serve on Pilchuck’s board.

In a 1982 interview at Pilchuck, Joey Kirkpatrick speaks with Paul Hollister about her work with Flora Mace, discussing the importance of open forms in their work, glass colors, complexity in the blowing of their pieces, and their wire drawing process.

08:41 Transcript

Klaus Moje talks with Paul Hollister about color in his work, purposely using a limited number of molds, and reworking a new piece in a 1982 interview at Pilchuck.

04:51 TranscriptJoey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace Interview for Paul Hollister, September 30, 1983.

Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick discuss their work, in a recording made for Paul Hollister.

(Rakow title: Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace interview [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168374)

Paul Hollister Interview with Klaus Moje, February 7, 1984.

Paul Hollister interviews Klaus Moje in Hollister’s apartment.

(Rakow title: Klaus Moje interview [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168459)

“Gefühle—personifiziert: Arbeiten von Flora Mace und Joey Kirkpatrick / Personification of Feelings: The Mace/Kirkpatrick Collaboration.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): 14–19.

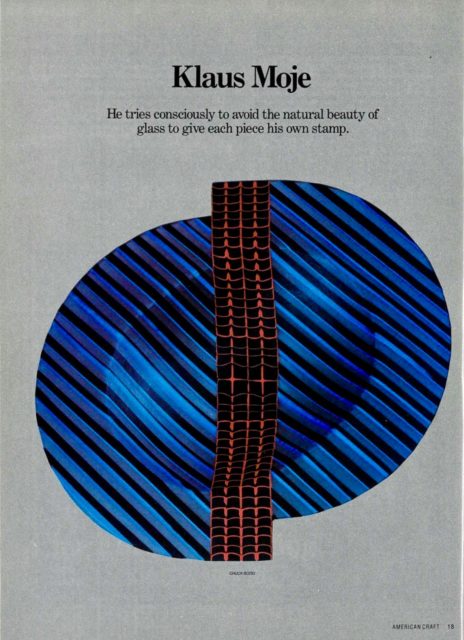

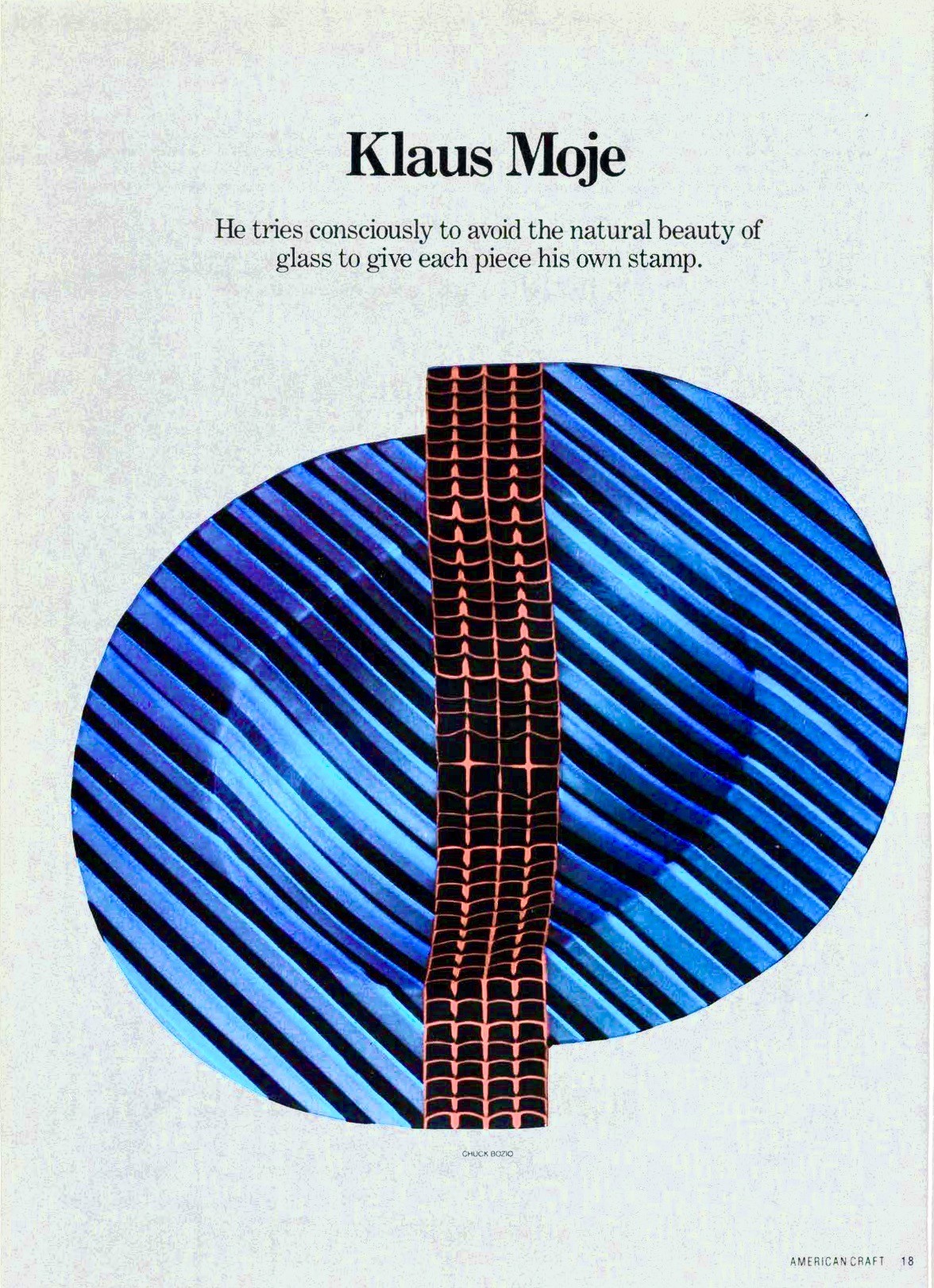

“Klaus Moje.” American Craft 44, no. 6 (December 1984/January 1985): 18–22.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/13720/rec/33

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol44No06_Dec1984

Paul Hollister, “Gefühle—personifiziert: Arbeiten von Flora Mace und Joey Kirkpatrick/Personification of Feelings: The Mace/Kirkpatrick Collaboration,” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1984): p. 14.

Paul Hollister, “Klaus Moje,” American Craft 44, no. 6 (December 1984/January 1985): p. 18.

Paul Hollister, “Klaus Moje,” American Craft 44, no. 6 (December 1984/January 1985): p. 19.

Artist-in-Residence Thomas Buechner (left) and William Morris (right) in the hot shop at Pilchuck Glass School, 1982. Photo: Henry Halem.

William Morris discusses how studio glass equipment standards were erratic in the seventies.

00:39 Transcript

Flora Mace, Joey Kirkpatrick and Laura Donefer reflect on women’s experiences at Pilchuck Glass School, tell glass artists’ travel stories, and discuss working during Covid-19.

Flora Mace (left) and Joey Kirkpatrick (center, with torch) creating their wire drawing cylinders at Pilchuck Glass School, 1982. Photo: Henry Halem.

Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick, Doll Drawing Cylinders; entire series primarily made at Pilchuck Glass School,1979-1984. Glass and wire. Overall L: 8 to 14 inches. Image courtesy of Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace. Photo: Robert Vinnedge.

Dale Chihuly, Macchia Form, made at Pilchuck Glass School with the assistance of Flora Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick, 1982. Overall H: 14.1 cm, W: 13.8 cm, L: 22.3 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (83.4.144).

Dale Chihuly and Pilchuck

While Chihuly has maintained a strong relationship with Pilchuck throughout his career, he stepped down as a director early on to focus on his personal work. Numerous artistic directors have helped shape the school over the years, beginning with Mimi Pierce in 1973; others include Alice Rooney, Marjorie Levy, and Tina Aufiero. Chihuly remained on Pilchuck’s staff as faculty coordinator for nearly two decades after its opening. He also taught and was an artist-in-residence at the school for many years. Additionally, he acted as an advisor to the board of directors prior to joining the board in 1991. Subsequently he became a trustee emeritus and continued as a member of Pilchuck’s International Council.

Joey Kirkpatrick, Dale Chihuly, and Flora Mace at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine, 1985. Image courtesy of Joey Kirkpatrick and Flora Mace.

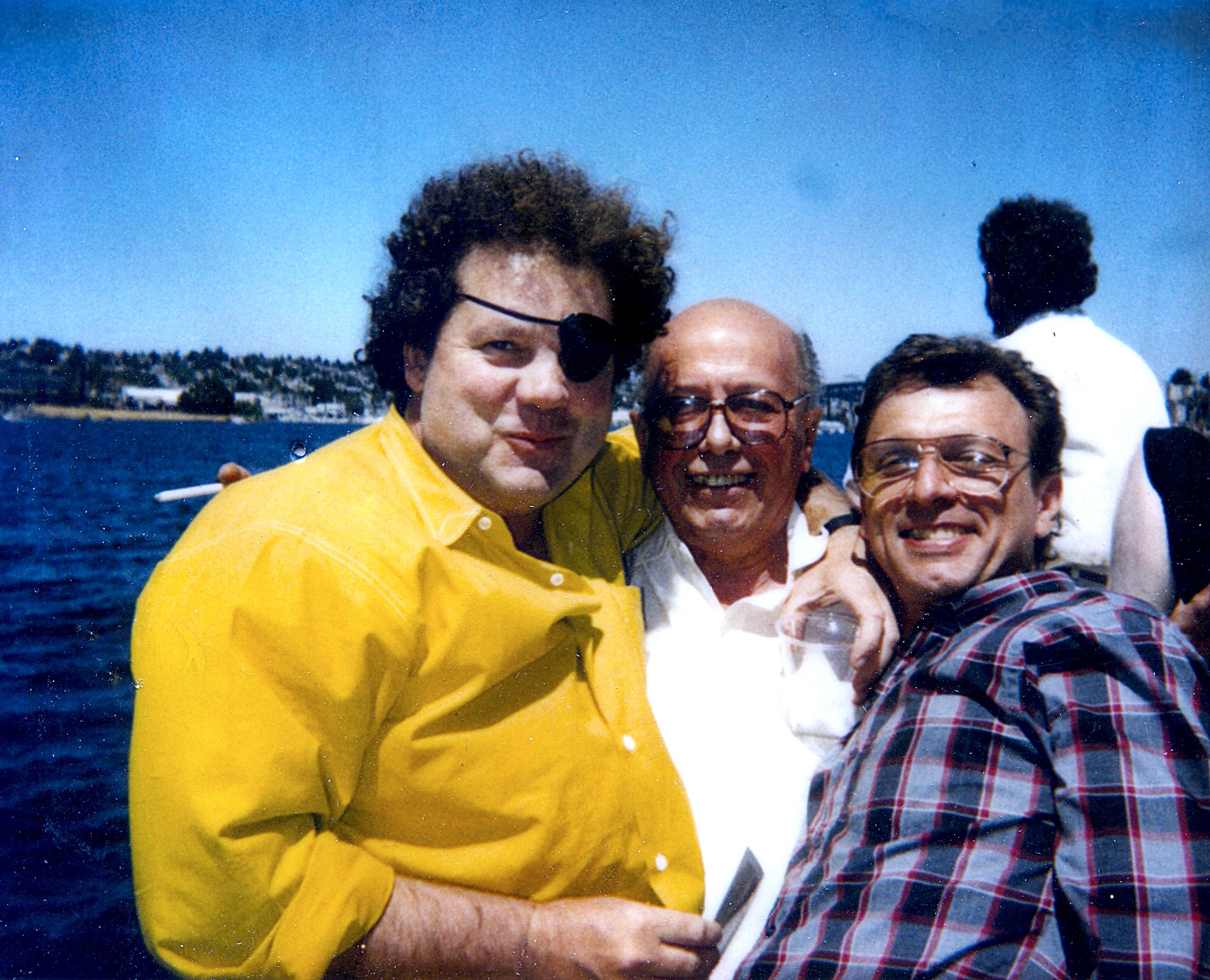

Dale Chihuly, Stanislav Libensky, and Henry Halem on Lake Washington, 1989. Image courtesy of Henry Halem.

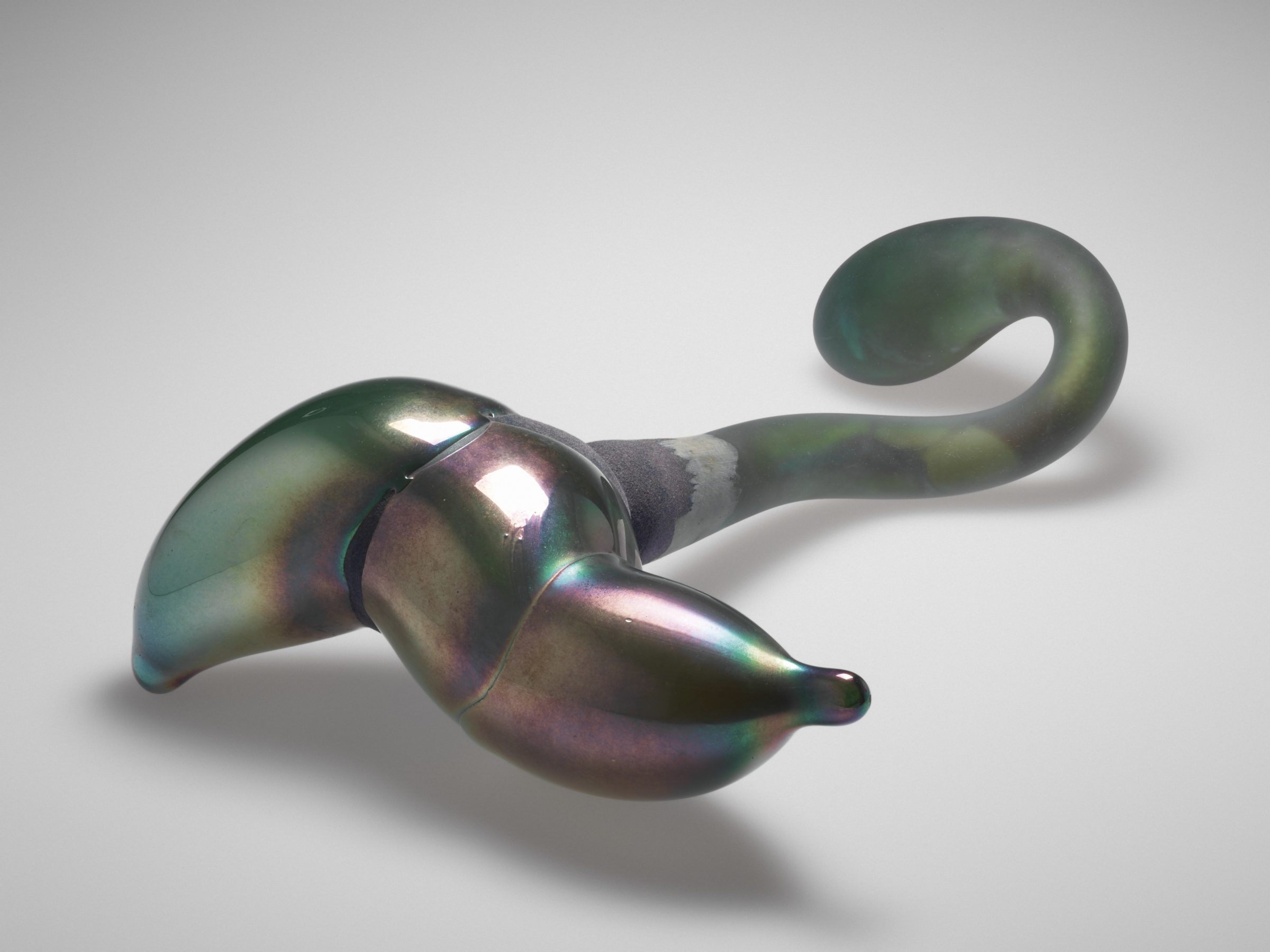

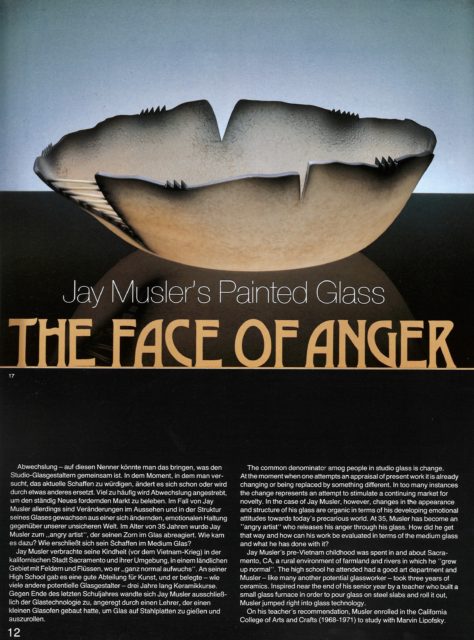

West Coast Glass

Pilchuck Glass School has attracted a large number of glass artists to the West Coast. Although glass that comes out of Pilchuck does not have a defined character per se, under Chihuly’s influence Pilchuck played a key role in making the West Coast one of the centers of blown work in the U.S. The Seattle area became known for its highly trained, skilled artists in part because of the steady presence on Pilchuck’s faculty of international glass masters, who imparted glass techniques unknown in the U.S. to the school’s American students. Other schools and hot shops, including Glass Eye Studio and Pratt Fine Arts Center in Seattle and Bullseye Glass Company in Portland, Oregon, sprang up in the region and became additional training grounds for glass artists. Traditional European glassworking knowledge spread to other places on the West Coast as well. Renowned makers such as Marvin Lipofsky, who taught at California College of Arts and Crafts and the University of California-Berkeley, and Richard Marquis, from the University of California-Los Angeles, had traveled to Europe early in their careers. Both brought back skills—Venetian murrine and millefiori techniques, in the case of Marquis—that they passed on to their students. Jay Musler and Flo Perkins, students of Lipofsky and Marquis, respectively, remained in the western United States and established their own reputations. New generations of makers from the Seattle area, such as Dante Marioni—son of studio glass artist Paul Marioni—and Native American artist Preston Singletary, worked closely together and continued to have strong ties to Pilchuck.

Marvin Lipofsky (left) and Gianni Toso, Murano, 1972. BGC Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

Marvin Lipofsky, California Loop Series 1969 #29, 1969. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. (2006.4.151).

“One of the key figures was Dale Chihuly. One of the other key figures…was Marvin Lipofsky. And, they traveled a lot to Europe. And then subsequent Fulbright scholars Jamie Carpenter, Ben Moore, Dick Marquis…and then on and on.”

“As far as Marvin [Lipofsky] bringing people in [to the California College of Arts and Crafts], he brought people in from Europe and from the States—to Oakland, where the campus was at the time. And he would make sure that we were all there and that we participated. He brought in people from Sweden, and from Italy, and various other European cities. And also, he brought in people from the States, and from the Midwest, East Coast, and—you know, whereas a person like me wouldn’t have that exposure, and here it was right in front of me. And it was a good experience to be there.”

Jay Musler Interview for Paul Hollister, October 11, 1984.

Jay Musler discusses his work in a recording made for Paul Hollister.

(Rakow title: Jay Musler interview [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168398)

“Jay Musler’s Painted Glass: The Face of Anger.” Neues Glas, no. 1 (January/March 1985): 12–19.

Flo Perkins, Los Angeles, c. 1978–79. Image courtesy of Flo Perkins. Photo: William Agnew.

“It’s funny, cause I’m from Boston and I went to school in Philly. New York never grabbed me. And then see [in the seventies], they really didn’t have a viable glass scene that I was interested in. It wasn’t so much blowing. Maybe it was more something else. And so that’s why I went west.”

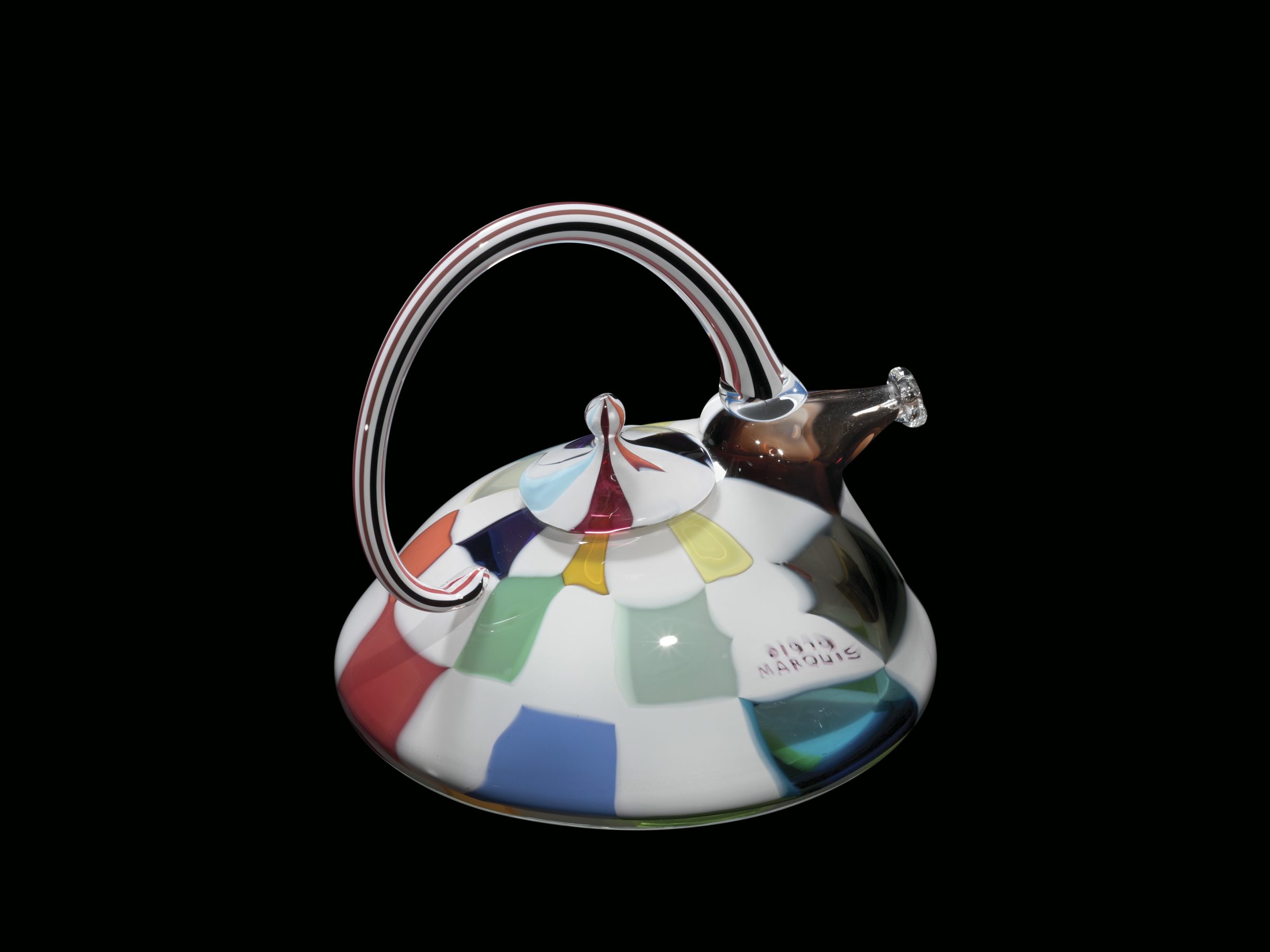

Richard Marquis, Checkerboard Teapot, 1979. Overall H: 12 cm, W: 14.1 cm, D: 13.7 cm. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York; gift of the Ben W. Heineman Sr. Family. (2007.4.172).

Flo Perkins, Earthquake Ware, 1979. Glass and silicone. Image courtesy of Flo Perkins.

Flo Perkins talks about going to Pilchuck, Mass Art, and then UCLA with Dick Marquis.

02:10 TranscriptFlo Perkins discusses the spining technique she first used at UCLA for her “Earthquake ware.”

01:35 Transcript

Glass Editor Andrew Page talks about Pilchuck and the differences between West Coast and East Coast glass.

02:32 Transcript“There’s some differences [between East and West Coast glass]. And, and we’ve actually taken [collectors] groups to explore that very topic. The East Coast artists, like Howard Ben Tré, Dan Clayman, Dan Dailey. They almost have a little bit of a different aesthetic than the West Coast, and the West Coast is dominated by Pilchuck….There’s much more emphasis on blown glass. And so that is different than the East Coast.”

Pilchuck: 21st Century

Pilchuck has continued to thrive as a center for glass education and experimentation, but it has always kept the memory of its roots. In 2001 a totem pole depicting Pilchuck’s founders Dale Chihuly, John Hauberg, and Anne Hauberg was created by artists Preston Singletary, David Svenson, and Native wood carvers from Haines, Alaska, and erected at the school. In recent years, under the leadership of Tina Aufiero, Pilchuck expanded its course offerings in innovative directions and developed partnerships and programs to reach new audiences, especially young people. Classes have explored the use of digital technologies in glassmaking, including 3-D printing, and have focused on making objects, such as glass pipes, that have been under-recognized in the glass field. Aufiero, who was a student at Pilchuck in 1979, earned a BFA from RISD in 1981 and taught at Pilchuck before being appointed as the school’s artistic director in 2013. She stepped down in 2018 to pursue her own art full time. Another RISD graduate, Ben Wright (MFA 2009), was named artistic director the following spring. Wright had previously served as director of education at UrbanGlass (2014–19), in Brooklyn. Pilchuck commenced its fiftieth year in 2021.

Preston Singletary discusses his development as a glass artist and making work that fuses the traditions of European glassblowing with his Tlingit cultural heritage.

31:25

Preston Singletary adds the glass potlatch hat he created to the Founders Totem Pole at the dedication ceremony at Pilchuck in 2001. Image courtesy of Preston Singletary Studios. Photo: Russell Johnson.

You know, at the time when we installed this—it didn’t seem risky at all when I was doing it. I always just kind of describe it as David [Svenson] and I sort of in a heroic moment placing the hat on top of the totem, but I remember when I was up there and fixing it, you know, you’re screwing it on, so there’s a threaded rod that’s going up through it, and we drop it onto the threaded rod to sort of hold it in place, and I looked down and there were like 250 people below me. It was just kind of a magical moment. Everybody’s staring up at you [laughs]. It was very surreal. But it was kind of like a dream, you know, that whole session.

Laura Donefer (center) with students in front of Pilchuck Hot Shop, 2018. Image courtesy of Laura Donefer.

Guest artist Rik Allen at Pilchuck, 2018. Image courtesy of Laura Donefer.

“Pilchuck is coming into its 50th year of existence [in 2021] in what is clearly one of the most challenging periods of that history. Having just canceled our second season in a row, the immediate challenges of hosting a program devoted to bringing participants from all over the world to experience a deeply symbiotic learning experience amidst a pandemic are very apparent. Pilchuck is an experience rooted in the remarkable residual energy of generations of artists gathering amidst a forest of sentient beings to study the mysteries of glass. That is not a holistic experience that is easily translated to digital and remote realms. But we must learn from this as an organization and a planet as even bigger challenges face us on the other side. The existential challenges of Pilchuck and indeed the larger glass world are simultaneously our biggest opportunities. We must create a more accessible and inclusive experience leading to a more representative community and pursue sustainable ways to work with glass that honor and respect the stunning natural environment in which we are located.”