Penland School of Craft

Penland, NC

Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft. Photo: Robin Dryer.

Introduction

Penland School of Craft was founded by Lucy Morgan in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains in 1929 as the Penland School of Handicrafts. Originally focused on reviving weaving traditions, the school soon expanded into teaching pottery, basketry, and metalwork. In the 1960s, Bill Brown, Penland’s second director, quickly embraced the emerging possibilities of studio glass, adding a furnace and glass courses to the school. Penland was one of the first places where individuals could go to learn glassworking outside of the university system. Brown also added iron to the curriculum; established Penland’s ongoing multiyear fellowship programs and residencies to help support artists as they developed their professional careers; and added longer, more intensive fall and spring class sessions to the school’s numerous short offerings during summer sessions. Penland has no standing faculty; instead, it employs full-time studio artists as well as university-based educators from around the world to teach in its immersive, experiential workshop format. Penland promotes the open sharing of craft knowledge and experience during its workshops, which facilitate intense periods of interaction and exchange among visiting artists and students.

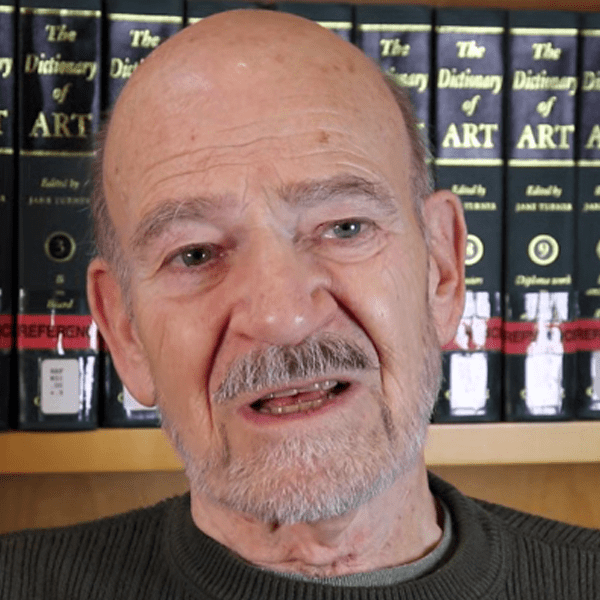

This section explores Penland’s importance as an incubator of the studio glass movement and also details Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, the first-ever large-scale workshop to demonstrate the little-known process for creating encased flamework paperweights using only a torch. It features excerpts from interviews and correspondence with Gary Beecham, Donavon Boutz, Ken Carder, Randall Grubb, Henry Halem, Carey Hedlund, Douglas Heller, Robert Levin, John Littleton, Jay Musler, Mark Peiser, Flo Perkins, Yaffa Sikorsky-Todd, Susie Silbert, Paul Stankard, Debbie Tarsitano, Gay LeCleire Taylor, Victor Trabucco, Kate Vogel, and Toots Zynsky, conducted between 2016 and 2020. It also contains excerpts from interviews conducted by Paul Hollister with Stephen Dee Edwards (1983), Gary Beecham (1981), Mark Pesier (1979), and Richard Ritter (1979) and a consulting session with Geraldine Casper (1974). Full transcripts from Hollister’s interviews with Peiser, Beecham, and Casper are included, as well as highlights from the Paul Hollister Slide Collection, footage from Stankard’s workshop, and writings by Hollister, including two articles about Stankard and accounts of Hollister’s involvement with the Glass Art Society.

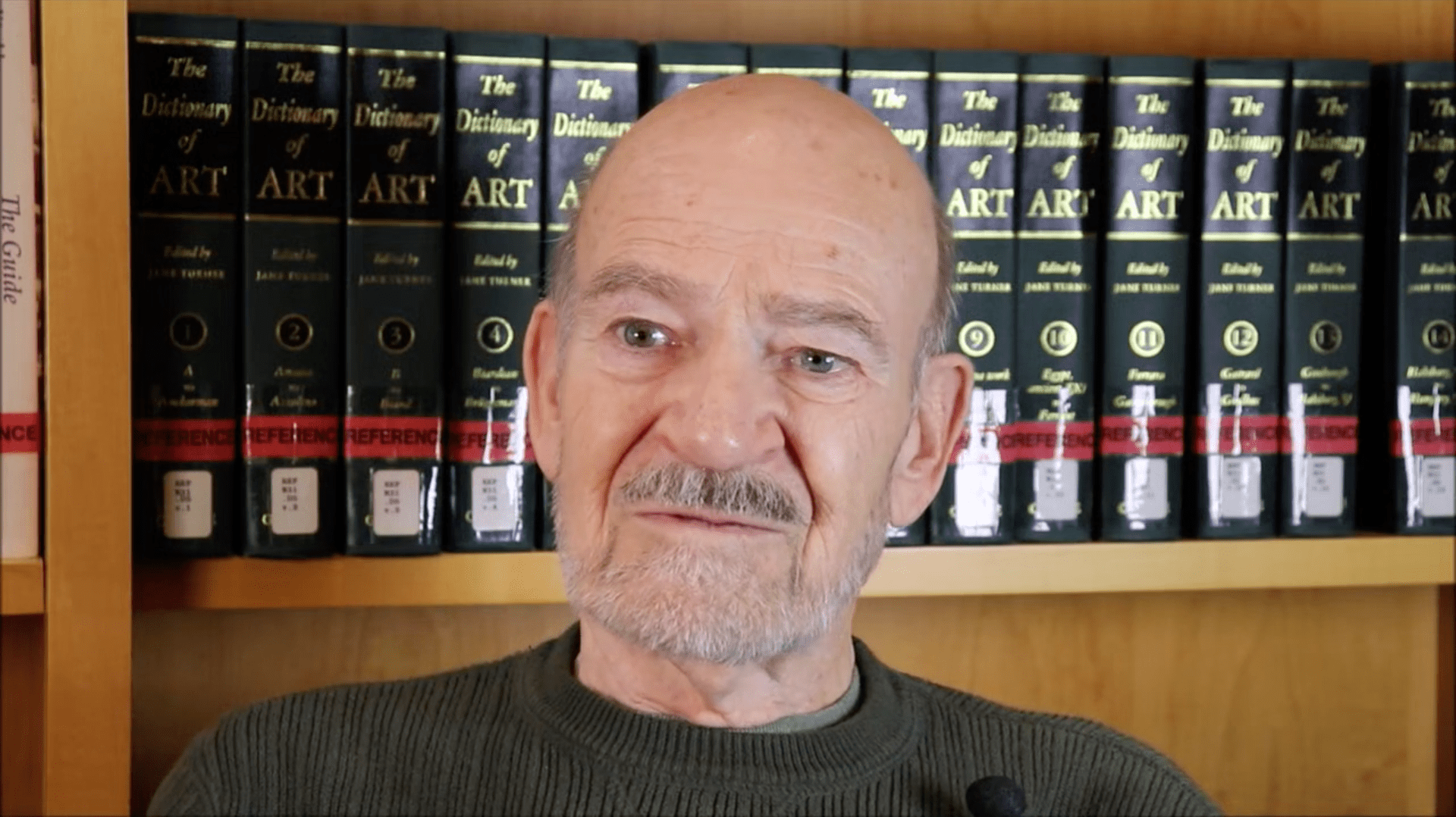

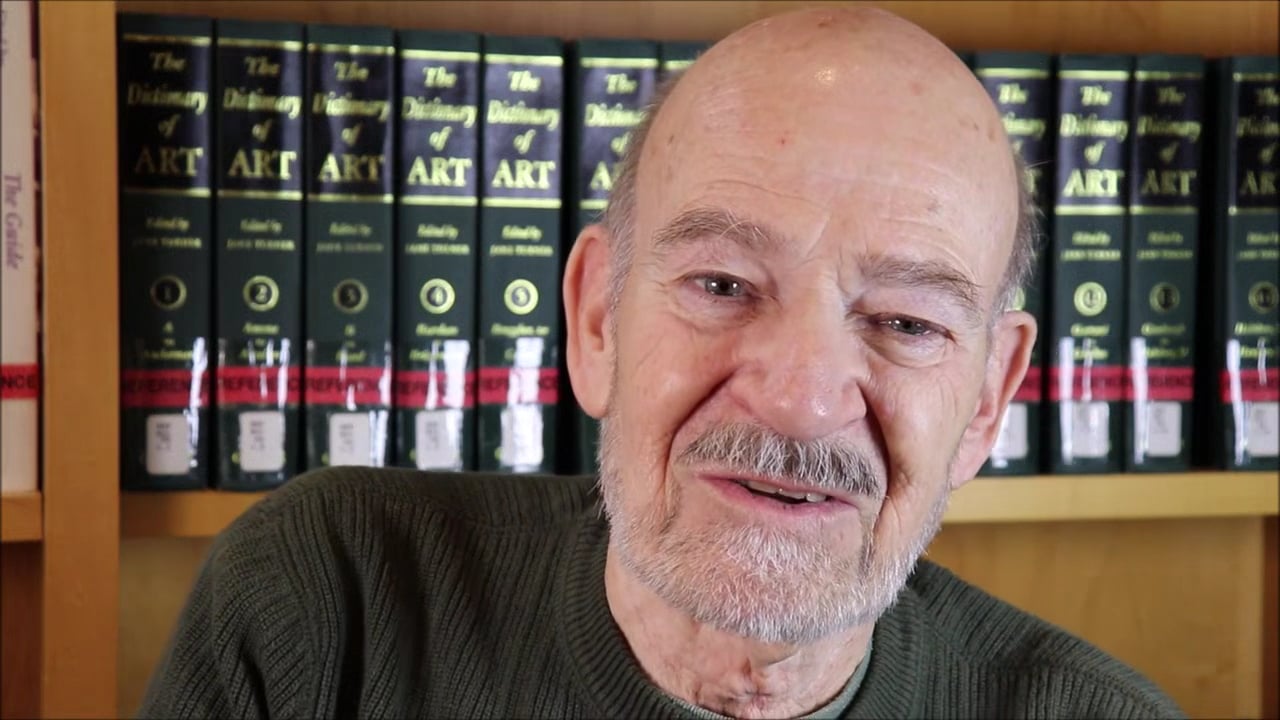

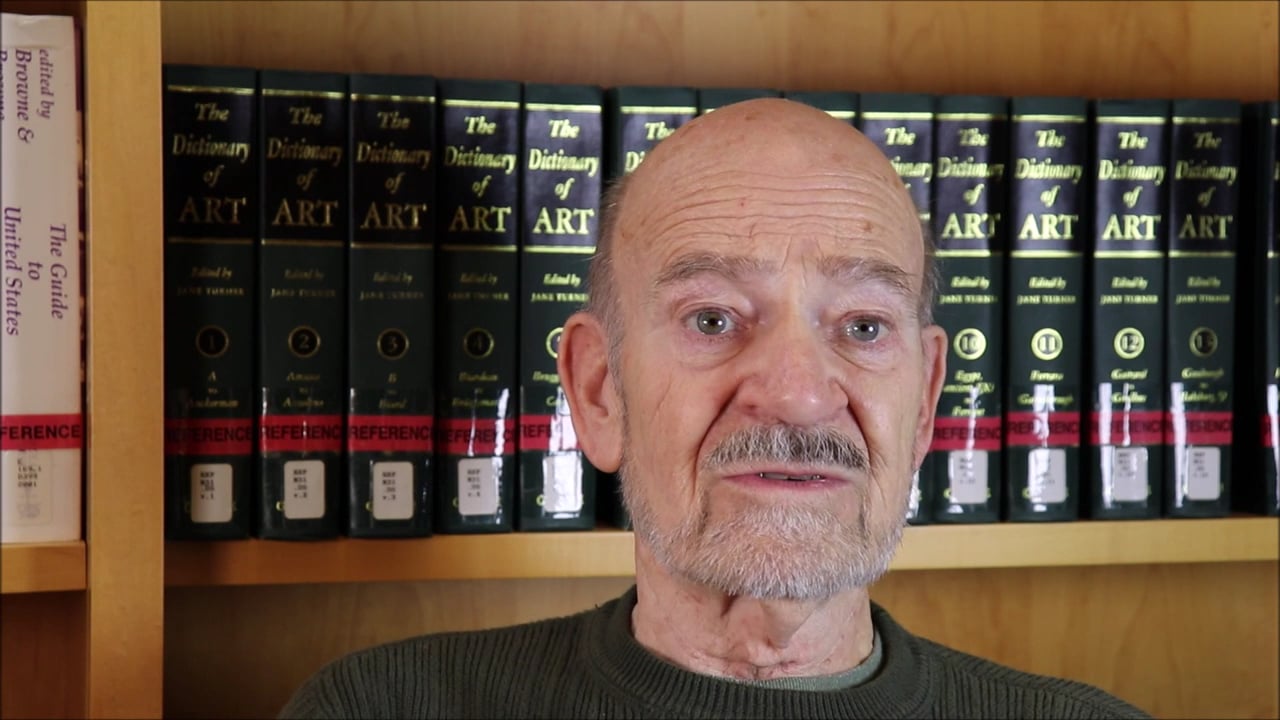

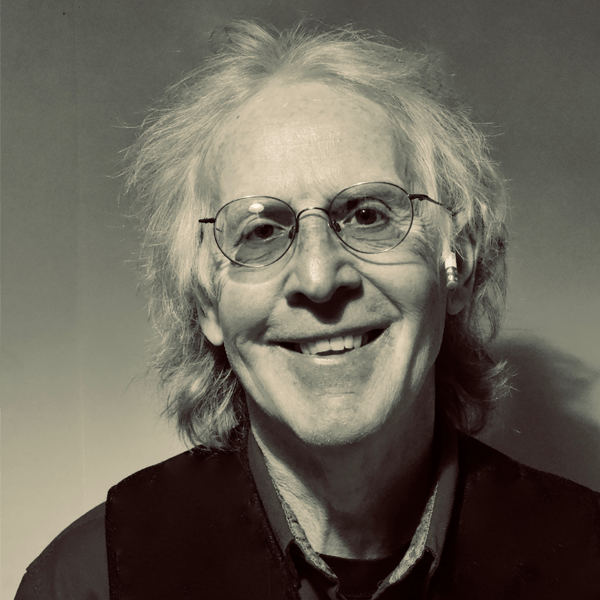

Glass artist Ken Carder discusses the importance of the Penland School of Craft as an “environmental utopia.”

01:55 TranscriptKen Carder discusses the importance of Bill Brown’s artists’ residency program at Penland.

02:36 Transcript

Susie Silbert, Corning Museum of Glass curator of modern and contemporary Glass and former assistant to Mark Peiser, discusses Penland.

00:57 TranscriptStudio Glass at Penland

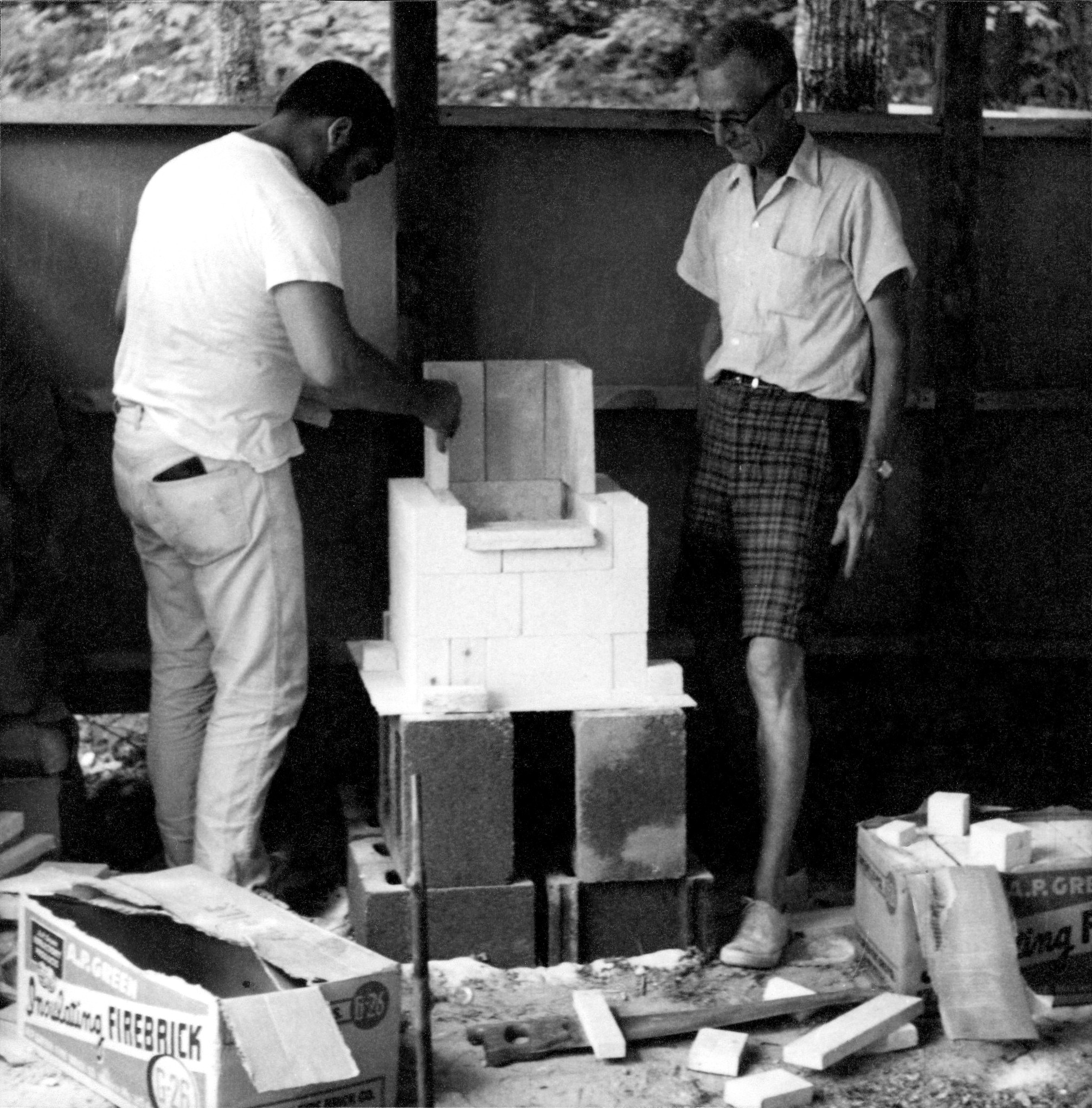

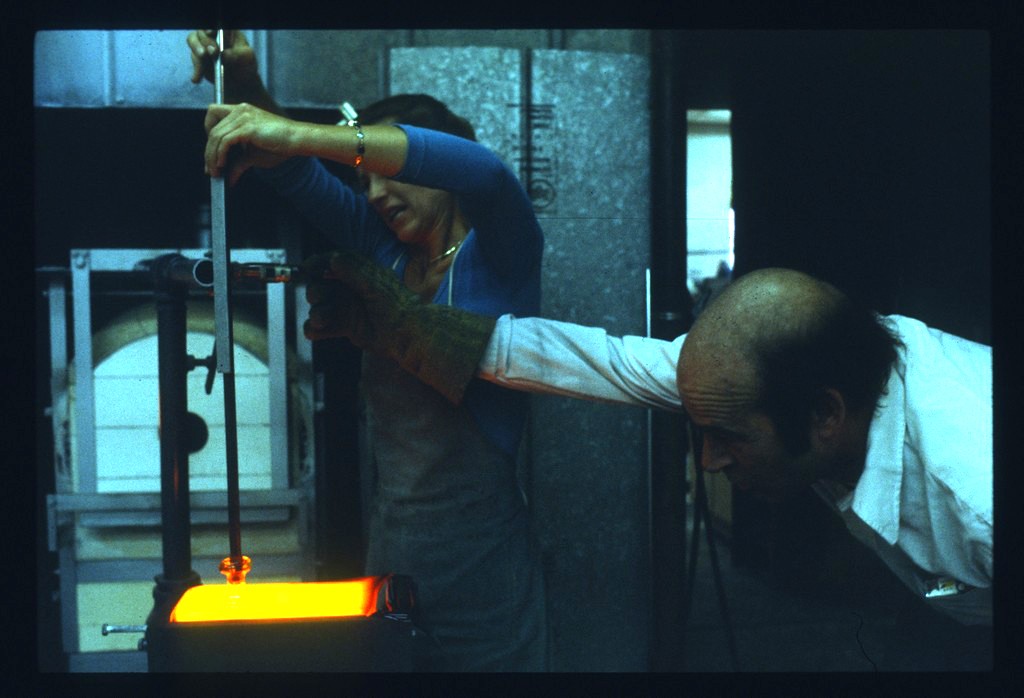

In 1964, shortly after establishing his renowned artists’ residency program, Penland director Bill Brown attended the first World Craft Congress of Craftsmen in New York City, where he witnessed studio glass innovator Harvey Littleton blowing glass in a small furnace set up in a courtyard. Impressed, he decided to build a glass furnace at Penland. A conversation with Littleton led to Bill Boysen, one of Littleton’s students, coming to Penland the following year to help build its first glass studio. Boysen and Brown built the facility from the ground up, with assistance by local ceramicist Cynthia Bringle, who taught clay at Penland.

Two years later, in 1967, artist Mark Peiser came to Penland from Chicago to attend its summer program in glass, at the end of which he became the school’s first resident craftsman in the medium. Although his residency was supposed to last three years, Peiser, with a background in science, engineering, and industrial design, stayed on at Penland and became an influential figure, creating his own glass formulas and shaping the program’s profile. He built his own studio near the Penland Barns (the campus’ housing for resident artists) in 1970 and eventually gifted it to the Penland School when he constructed a new workspace. The original building became known as the Bill Brown Resident Glass Studio. Other artists who held residencies at Penland during the studio glass movement’s formative years include Katherine Bernstein, William Bernstein, Fritz Dreisbach, and Richard Ritter.

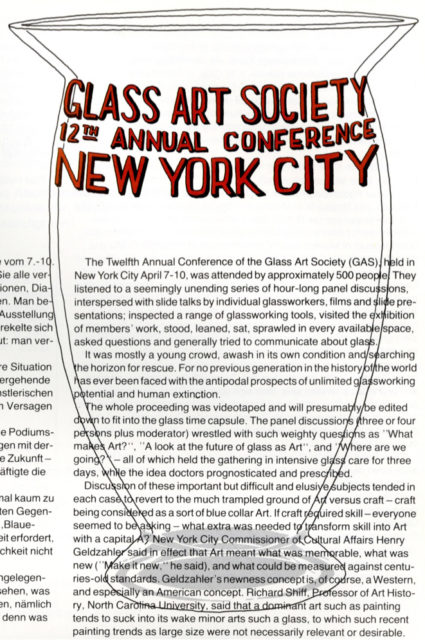

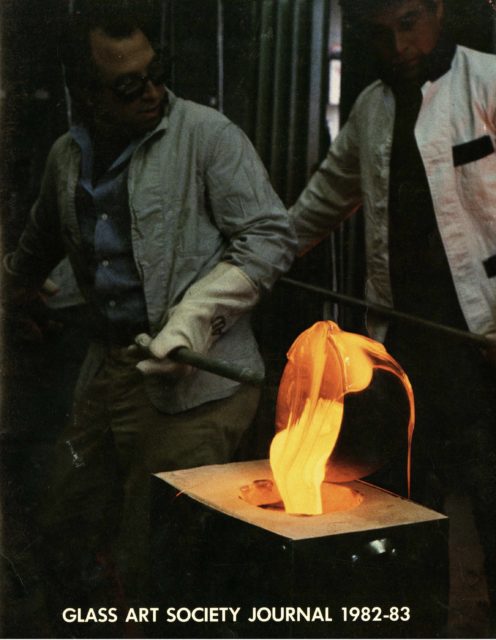

In 1971, Peiser cofounded the Glass Art Society (GAS) with William Bernstein and Fritz Dreisbach; its first two annual meetings were held at Penland. GAS was vital to the formation of a professional studio glass community. Paul Hollister reported on the 1982 GAS conference in New York City, where he also was a panelist in the discussion “What Makes Art?” Hollister likewise wrote about the 1984 GAS conference in Corning, New York, and contributed to the Glass Art Society Journal.

“Glass Art Society 12th Annual Conference, New York City.” Neues Glas, no. 2 (1982): 105–6.

“What Makes Art?” With Henry Geldzahler, Richard Shiff, and Thomas Buechner. Glass Art Society Journal (1982): 5–11.

“GAS in Corning.” American Craft 44, no. 4 (August/September 1984): 94.

Article: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/13513/rec/5

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol44No04_Aug1984

Bill Brown (left) and Bill Boysen (right) building Penland’s first glass furnace and studio, Penland, North Carolina, 1965. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft.

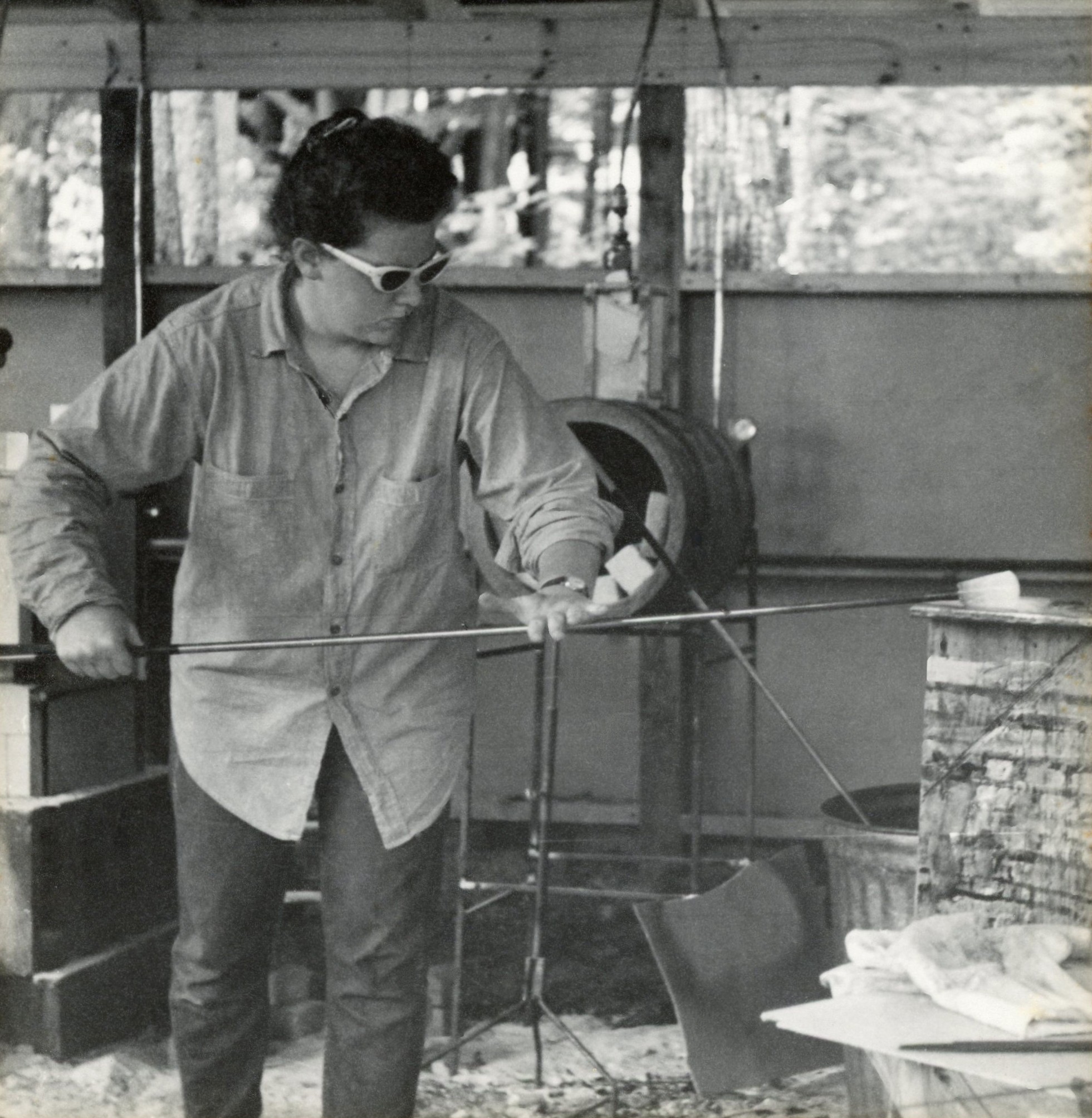

Cynthia Bringle at Penland’s first glass studio, Penland, North Carolina, 1965. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft.

Kate Vogel and John Littleton discuss Bill Brown’s development of a glass community in North Carolina’s Southeast.

02:43 Transcript

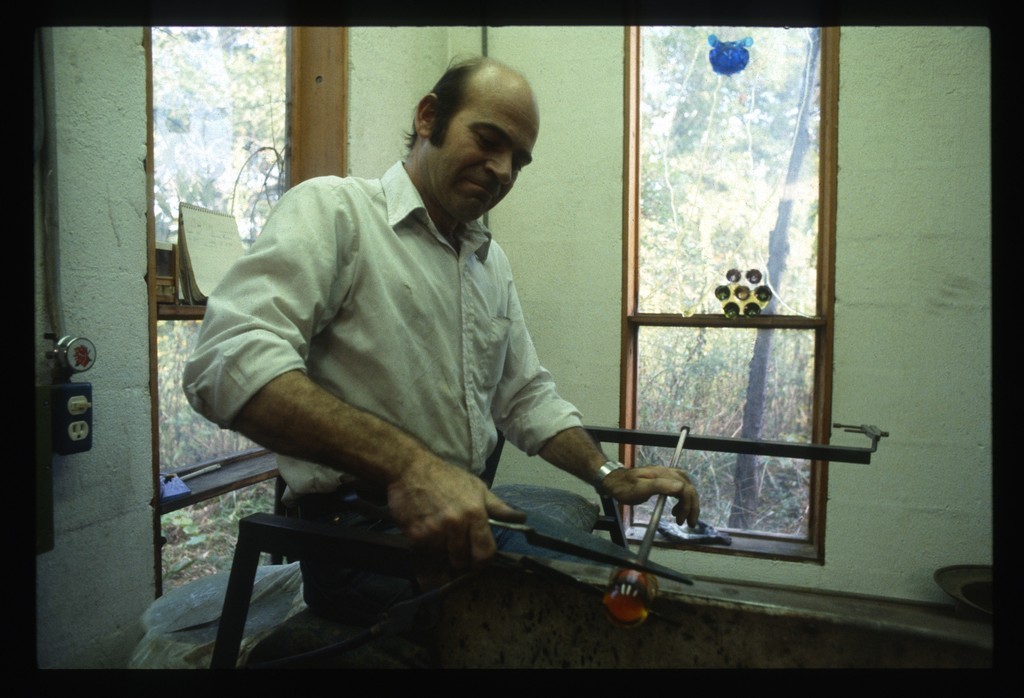

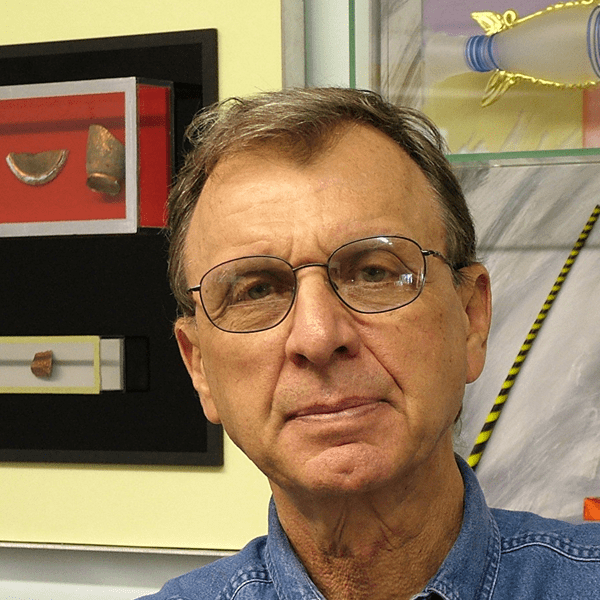

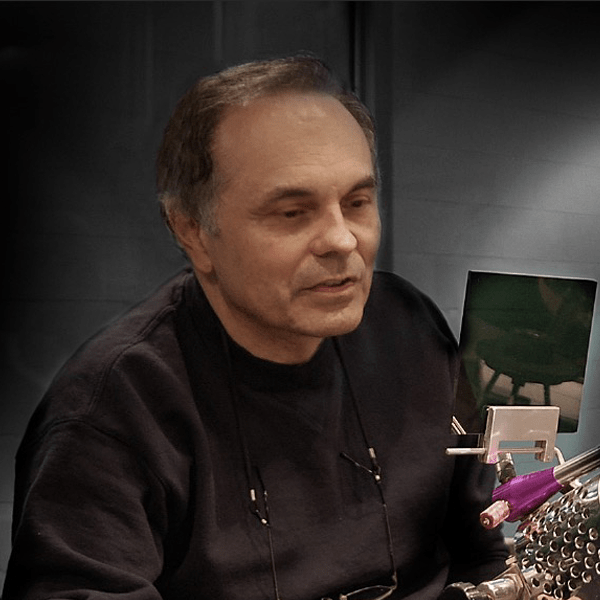

Mark Peiser talks about the early studio movement, glass marbles, and teaching himself to blow glass.

1:08 Transcript

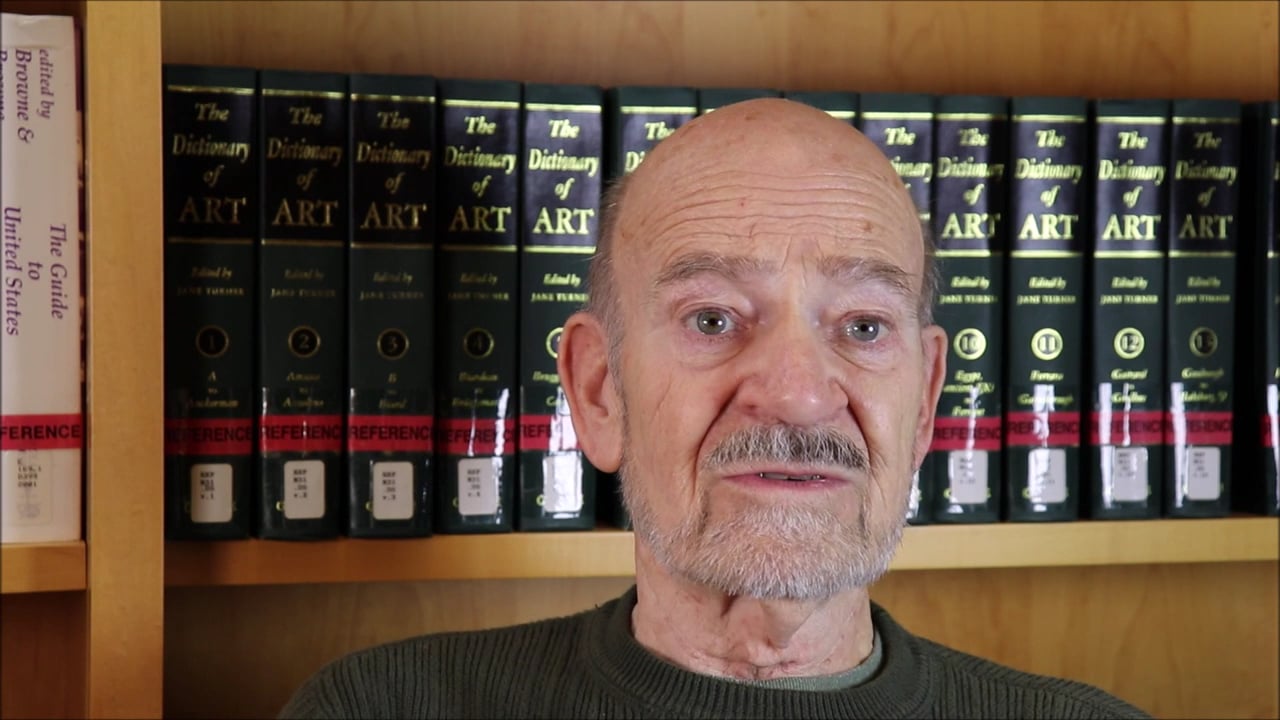

Mark Peiser at the bench of his studio, built in 1970. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

“I love the guy and his independence. And his studiedness. The way he has studied what he does, and just goes out on his own and isn’t influenced by anything other than, I think, himself.”

Henry Halem talks about all glass artists except Mark Peiser buying their color from manufacturers.

“Roni Horn and I were speaking with [Mark Peiser], and Roni was particularly fascinated with the color and the formulas for color and [asked if] could she talk to him about it, and he picked up his two notebooks and handed them to Roni, all his research, and said, ‘I’m gonna be here for two days. Get what you want out of them.’ And that was for me the sort of ‘raise the bar to way up there’ about generosity and sharing of information. And later Roni was just behind me in school, a year or two actually, and I went back to Providence, and I visited her, and she opened me up this beautiful little secondhand suitcase, raised the lid, and in it were two by two by, probably, three-eighths of an inch little squares of, I don’t know how many, this range of color that she had been practicing making from Mark’s formulas. And I just, I thought, ‘He is a wonderful and amazing person.’”

Mark Peiser with assistant Joanne Chamberlain casting a piece from Peiser’s Moon Series, c. 1984. Photo: Anne Hawthorne.

“There’s a closet in [Mark Peiser’s] studio that has almost every single primary source document of the studio glass movement. So for the four years that I worked with him—living in a place where there were no real libraries and no other entertainment, I’ve read every single source document of the studio glass movement, and it was quite an education.”

Gay LeCleire Taylor speaks about the significance of Penland and Mark Peiser’s role in getting the glass program started.

00:28 Transcript

Susie Silbert talks about the experience of working for Mark Peiser and Richard Ritter at Penland.

02:21 Transcript

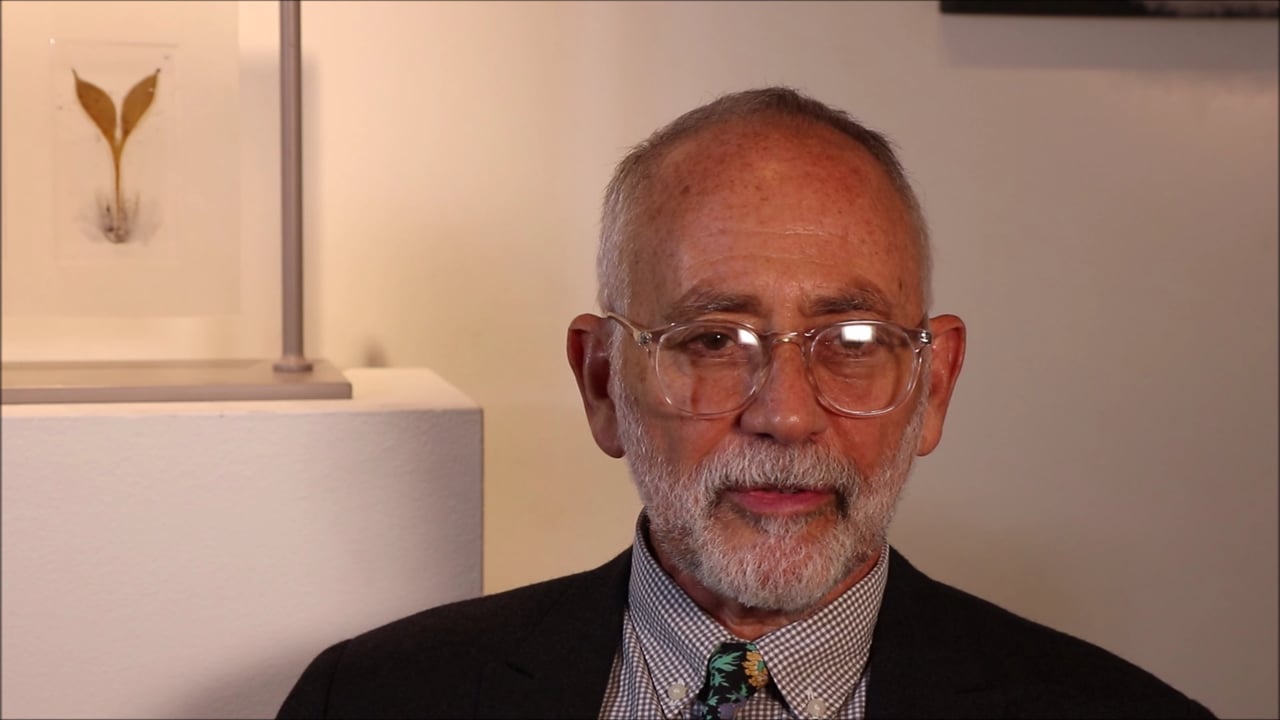

Former Penland archivist Carey Hedlund discusses the Penland School of Craft’s influence.

01:42 Transcript

Robert Levin talks about his experiences at Penland and the school’s importance to studio glass.

02:19 Transcript

Ken Carder discusses the high concentration of glass artists at Penland and in the surrounding area.

01:00 Transcript

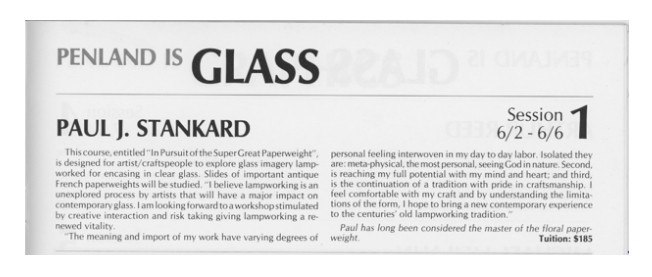

Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop

In June 1986, glass artist Paul Stankard led an unprecedented workshop at Penland on flameworking, also known as lampworking, a process in which glass is melted in a flame with a torch. Mark Peiser had suggested inviting Stankard to teach. While other glassworking processes, including blowing, casting, and slumping, were being rediscovered and freely shared by American artists during the 1960s and 1970s, flameworkers had largely kept their expertise to themselves. Stankard began to open the field in 1986, first with a one-hour demonstration of flameworked paperweight making at Wheaton Village (later Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center) in Millville, New Jersey, in the spring, and then with an intensive five-day summer workshop at Penland called “In Pursuit of the Super Great Paperweight.” Stankard personally invited Paul Hollister to attend this Penland session, which Hollister later described in print as an “extraordinary demonstration” that “marked the revelation in public of a specialized area of glass working hitherto persistently guarded as a trade secret by paperweight makers .”1

1 Paul Hollister, “Natural Wonders: The Lampwork of Paul J. Stankard,” American Craft 47, no. 1 (February/March 1987): 42.

Paul Hollister, “Natural Wonders: The Lampwork of Paul J. Stankard,” American Craft, 47, no. 1 (February/March 1987): pp. 36-37.

Mark Peiser talks about his interest in flameworking and his suggestion that Paul Stankard come to Penland to give his workshop.

03:03 Transcript

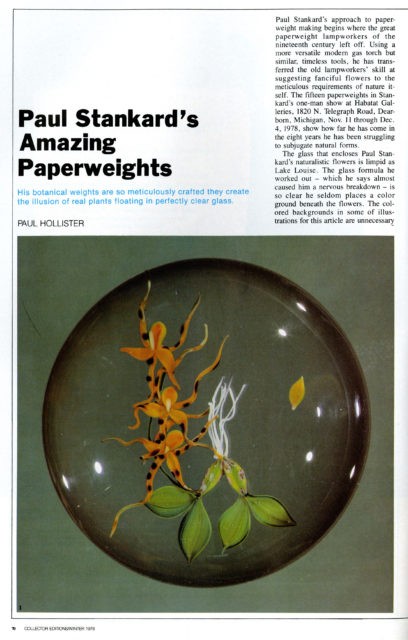

“Paul Stankard’s Amazing Paperweights.” Collector Editions 6, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 70–73.

“Natural Wonders: The Lampwork of Paul J. Stankard.” American Craft 47, no. 1 (February/March 1987): 36–43.

Full issue: https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll2/id/15025/rec/1

American Craft Council, Digital File Vol47No01_Feb1987

Course description, Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft.

Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio (no longer extant) where the majority of Paul Stankard’s workshop took place, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Introduction to “Two Days at Penland,” a video documenting Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Narrated by Geraldine Casper, then curator of the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum of Glass, and Jack Casper. Videography attributed to Jack Casper. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

00:43

Paul Stankard demoing and teaching, excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

03:10

Paul Hollister talks about paperweight maker Charles Kaziun’s secrecy and Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop in a 1987 lecture.

02:07 Transcript

In a recording by Paul Hollister of Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Stankard introduces Hollister, discusses Charles Kaziun and secrecy in paperweight making, and asks attendees what they wish to learn.

07:13 Transcript

Paul Stankard discusses giving a flameworking demo at Wheaton Village prior to his Penland workshop.

Participants

Workshop attendees ranged from novices to such established glass artists as Mark Peiser, Gary Beecham, Ken Carder, and Yaffa Sikorsky-Todd, several of whom had previously taught at Penland themselves. Most artists who had worked in paperweights at this point, such as Sikorsky-Todd, were only familiar with making paperweights at a tank furnace and had not practiced flameworking. Chris Buzzini and Randall Grubb, friends who worked together at Correia Art Glass in Santa Monica, California, were two of the few artists who specialized in paperweights in the group. George Fugate, a retired paperweight collector and maker, lent a large number of tools for the workshop. Dudley Giberson, an equipment maker and inventor who created a machine to quiet furnaces used by studio glass workshops worldwide, also attended, as did a young Matthew Buechner, son of Thomas Buechner, founding director of The Corning Museum of Glass and then-vice president of Corning Glass Works.

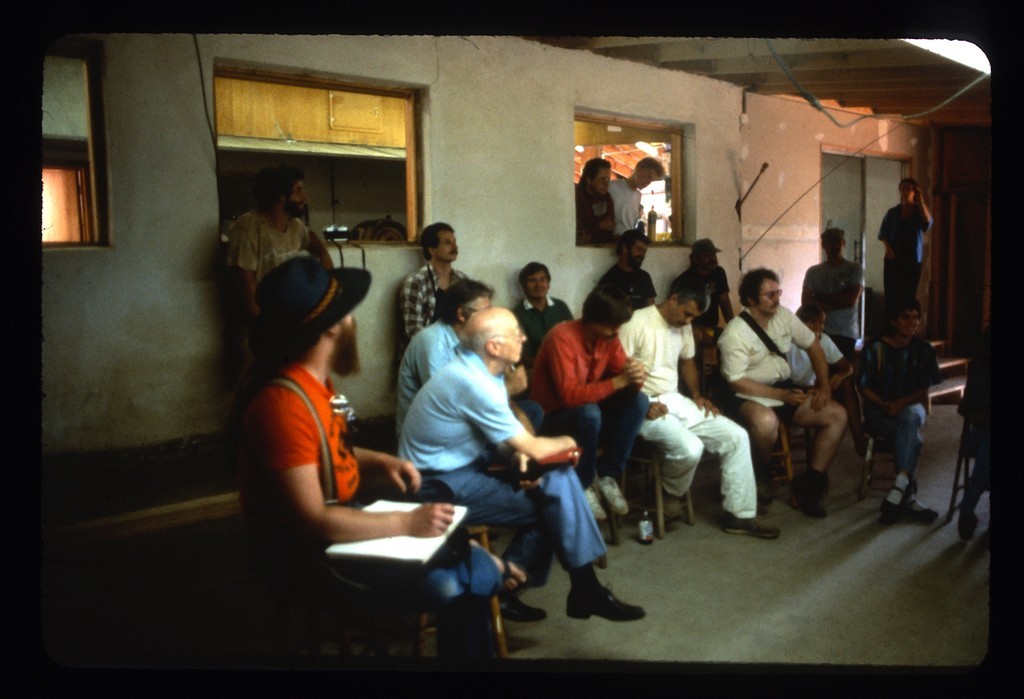

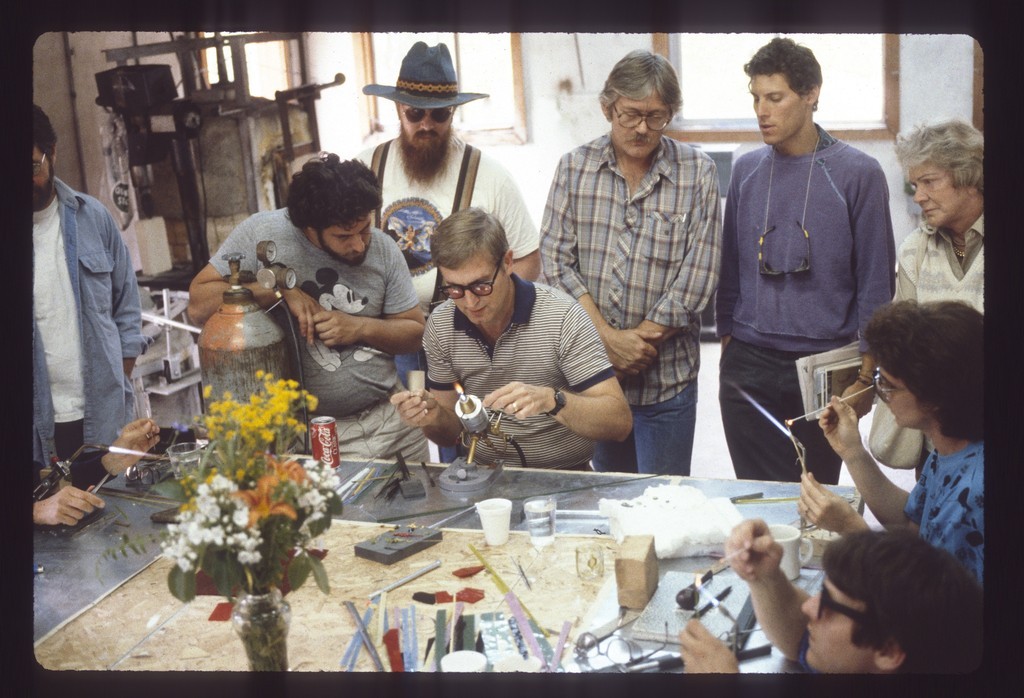

Workshop participants at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“This was magical. It was spontaneous. It took advantage of the best people in the Penland community and then brought in people from California—Chris Buzzini and Randy [Randall] Grubb.”

“Interestingly enough, everybody pulled from that workshop what they wanted. Some [weren’t] interested in working in glass. Most of them were professionals, and they’d kick back and just talked about possibilities, and it was very conceptual and it was a high-octane thinking-outside-of-the-box kind of thing.”

Workshop participants at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Mark Peiser discusses Dudley Giberson’s contributions to studio glass through his equipment developments and inventions.

01:32 Transcript“And so my take was I was learning. I knew how to make a paperweight, and I demonstrated all the nuances that I felt would satisfy the gang. I mean, it was kind of a rudimentary facility, but I did my job. But I was learning through the collective lectures. The thing that I was so proud of is they were very intelligent artists—I mean we’re not a bunch of yo-yos. The energy attracted a serious attitude.”

Chris Buzzini, West Coast paperweight maker. Still from “Two Days at Penland.” Videography attributed to Jack Casper. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Randall Grubb, West Coast paperweight maker, discussing his work. Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Videography attributed to Jack Casper. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

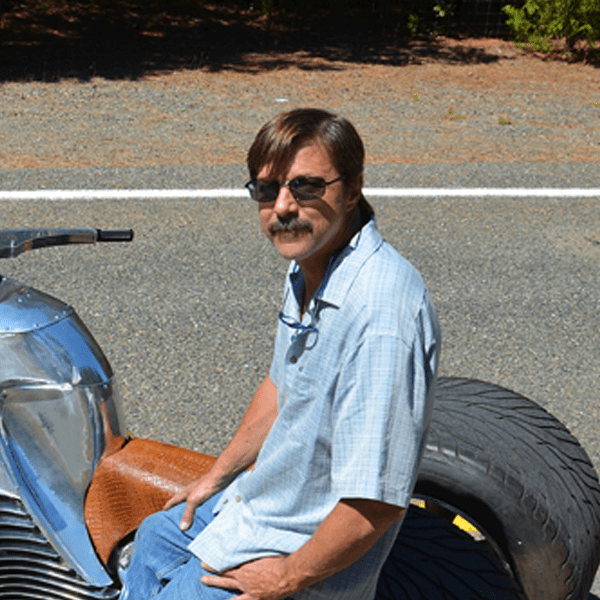

Randall Grubb talks about how he and Chris Buzzini had been attempting to make paperweights on their own.

02:06 TranscriptDemos

Paul Stankard began each morning of his five-day Penland workshop demonstrating flameworking techniques while students observed. Tutorials took place in the classroom of the school’s hot-glass studio or “hot shop,” then known as the Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio. The hot shop had a furnace but no flameworking area, so a small ancillary room for Stankard’s workshop was quickly assembled from plywood. A number of participants brought their own torches. Stankard showed students how to make paperweights using the torch and the furnace.

Paul Stankard demonstrating paperweight-shaping techniques at his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

“Now this is my first demo, making—this might have been my first demo making a paperweight. I’m shaping the paperweight, now Gerrie Casper’s husband is filming this one. And Paul Hollister is over to the left there.”

Creating a Flameworked Flower

Jack and Geraldine Casper’s “Two Days at Penland” video shows that on the workshop’s first day, Stankard demonstrated how to create a flameworked flower and encapsulate it in clear glass. William and Sally Worcester, Hawaii residents who had taught Penland’s spring concentration in hot glass, were class assistants.

Paul Stankard demonstrating the placement of flameworked components at his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

Paul Stankard discusses sharing paperweight-making techniques at his flameworking workshop.

01:11 Transcript“You know, it was interesting that people were—I’ve said it about a hundred times—people were really hungry to learn how to integrate flameworking into—that was my whole pitch—integrate flameworking into furnace working.”

Attendees observing flameworked components at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Debbie Tarsitano discusses formulating a new softer glass for paperweights with Chris Buzzini and her father, Delmo.

01:07 TranscriptPaul Stankard talks about what glassmakers like Yaffa Sikorsky-Todd learned from his flameworking workshop.

01:14 Transcript

Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

Yaffa Sikorsky-Todd talks about Paul Stankard sharing his flameworking techniques at his workshop.

00:38 TranscriptYaffa Sikorsky-Todd discusses Paul Stankard suggesting she and Jeff Todd title their new series of works.

01:23 Transcript“It was amazing, the whole experience. We kind of nestled into the hot shop. There was the glassblowing facility, and we took over the open space in the hot shop, and then we took over the other room. So the flameworking demos were done in the room adjacent to the hot shop.”

“Now Hollister told me, ‘Paul, you’re crowding ’em in, you’re crowding ’em in!’ And I was trying not to, but I couldn’t.”

Paul Stankard demonstrating how to add clear glass to a paperweight (with William Worcester assisting) at his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Ken Carder discusses the image [above] showing a cylinder that came out of a paperweight mold during the flameworking workshop.

00:30 TranscriptKen Carder talks about William and Sally Worcester’s role in Penland’s flameworking workshop.

00:37 Transcript“Paperweight [making] was not a public display technique. It was just not. I mean, it’s very, very difficult to put up a paperweight studio. You have to have certain equipment and a certain glass type and make things in a certain way to be able to produce the types of quality paperweights that people like myself and Paul [Stankard] and others made. So you can throw a little furnace up and a glory hole and be blowing glass and making shapes or forms pretty quickly. But you want a paperweight studio? I could say that [out of] most of the people that take classes, and this is probably true, only a small fraction of them will ever make the kind of paperweight studio that they can actually produce a piece like Paul makes or I make. It takes much more to do that than almost any other type of glasswork that you can try to assemble for yourself in the studio.”

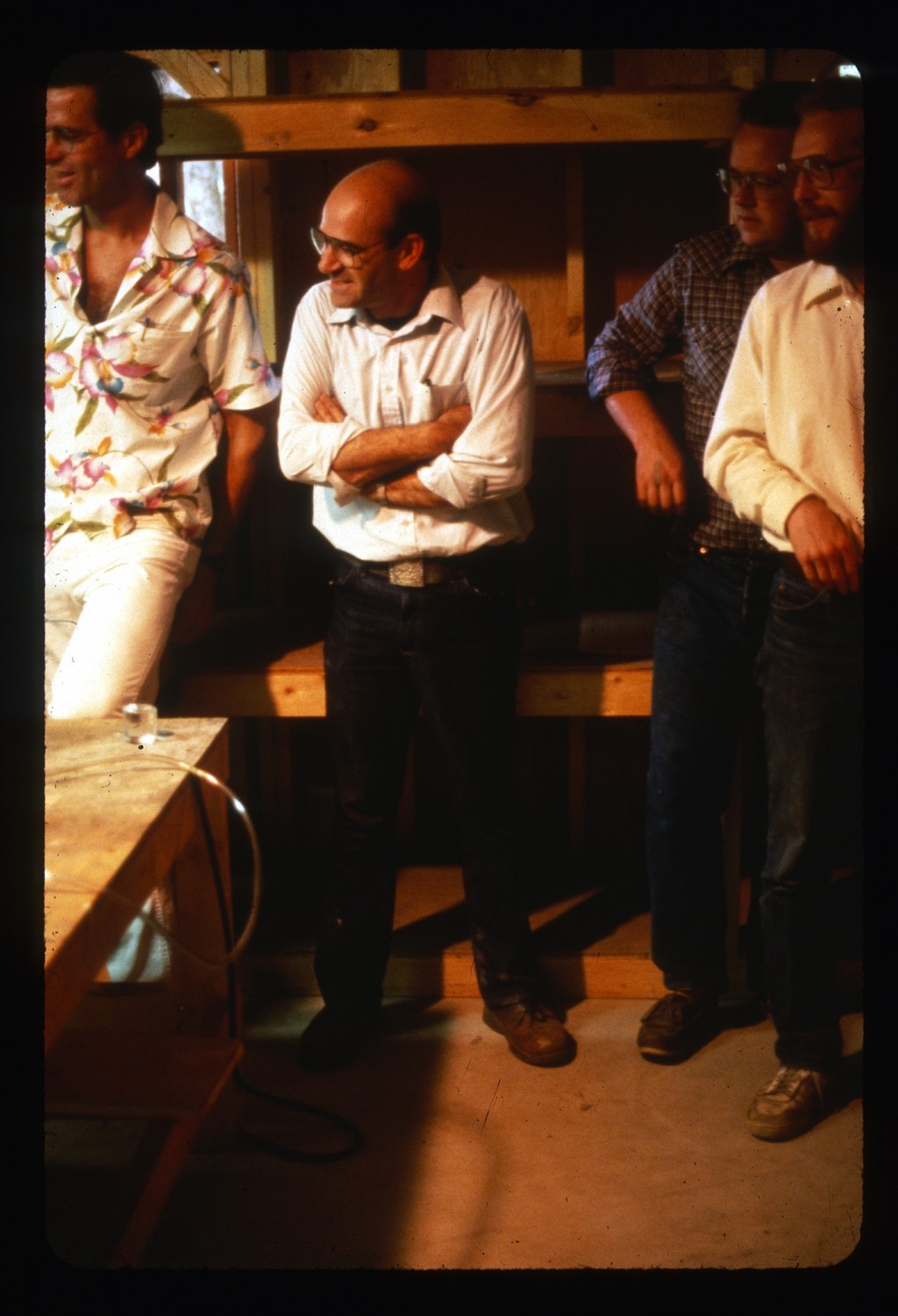

Workshop participants Richard Jolley, Mark Peiser, George Bucquet and Ken Carder at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Mark Peiser discusses his work. Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Flameworked “Root People”

During the workshop, Stankard also created flameworked “root people” for the audience. These components emerged from his development of paperweights meant to be seen in the round. The year of the workshop, Stankard’s newest series of Environmental paperweights featured earth and ground with flameworked figures or “spirits” beneath. These “root people” could be seen by lifting the paperweight to eye level or turning it over completely.

One of Hollister’s slides from this session shows a hot plate with a collar, flameworked components, and a vacuum pump. A big mystery for workshop attendees was how to encapsulate flameworked parts in clear glass. Several remember Mark Peiser exclaiming, “He just dumps it on!” when he first observed Stankard pouring hot glass into the collar. A vacuum pump, used to seal the components into the crystal, equally fascinated the group. Although well known in industry at this point, the use of a vacuum in paperweight making to remove air bubbles was new to most participants.

Paul Stankard’s flameworked components before encapsulation, made during his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Paperweight mold with figures at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Paul Stankard describes a slide showing set-ups waiting to be encapsulated in glass.

00:26 Transcript

Ken Carder talks about the paperweight set-up Stankard demonstrated in his flameworking workshop.

01:30 Transcript

“Something as simple as a vacuum pump just helped the contemporary [paperweight] artists elevate their work because it just gave this opportunity to do these three-dimensional designs they couldn’t have dreamed of before.”

Making

After the morning demos, workshop participants practiced making paperweights, beads, and other glass objects using Stankard’s techniques. Many of the students skilled at working with hot glass were particularly interested in incorporating furnace work with flamework. Combining these two techniques, Stankard felt, was a key draw of the workshop. To facilitate this, he brought a pick-up—a metal plate for “picking up” encased molten-glass designs—with a metal square “collar” large enough for the volume of glass used for furnace work. Penland later auctioned off a cube-shaped paperweight the class made with this apparatus to Harvey Littleton.

Paul Stankard discussing specialized flameworking apparatus for furnace working with Paul Hollister, Richard Ritter, and participants at his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Richard Ritter discusses experimentation with color mixing and progression in his work in a 1979 interview with Paul Hollister.

07:52 TranscriptPaperweights

Much of the workshop’s paperweight making was done as a group activity. Penland still has examples of paperweights made by attendees in their archives. In one assignment, attendees contributed lampworked elements to a large sculptural rectangle, not unlike what Stankard was creating at the time with his then-new Botanical series. Students also made their own paperweights: Gary Beecham made his first-ever “Millville Rose”—a flower-petal paperweight design made famous in Millville, New Jersey—with a crimp he recalls artist Joel Van Arsdale brought for the group. Beecham used the rose-shaped metal crimp to produce the weight’s distinctive decoration.

Flameworked floral components at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“And these are the components….they were going to be cast into a large block. And so we had the flameworking, which was the focal point, but we also used the glass furnace, I think there was only one—to make cast pieces. Most of the people were glassblowers, so they were more comfortable with the furnace.”

Randall Grubb talks about how tiny Paul Stankard’s flameworked elements actually are.

00:54 Transcript

Student Paperweights from Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Collection of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft. Photo: Carey Hedlund.

Gary Beecham’s “Millville Rose” made using Joel Van Arsdale’s crimp at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland school of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of Rago Auctions.

“Gary Beecham made a ‘Millville Rose.’ Actually, it was auctioned off at Rago Auctions. I talked to Gary about how to put together a ‘Millville Rose’ crimped paperweight. So Gary made this paperweight, and he yells out after he plunged the crimp into the glass: ‘This is the cheapest trick I’ve ever seen!’”

Millville Rose crimp with removable petals nailed into a cork base, undated. Collection of the Museum of American Glass, Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center, Millville, New Jersey (1992.012.005). Photo: Al Weinerman.

Paul Hollister Experiments

While not a glassmaker, Hollister fully participated in all facets of the workshop and experimented with the flameworking techniques. Stankard was impressed by a glass plaque Hollister made during the session that incorporated fusing with flamework. Hollister titled this piece—now in the collection of The Corning Museum of Glass—Gardens of Monticello.

Paul Hollister flameworking, Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

“He was a proper New Englander, but when he was surrounded by glass artists at Penland, I think that he really came alive. When he was at Corning, I’m sure—he was very upper class. When he was at Penland, he was just an artist like the rest of us.”

“What I remember about [Paul Hollister] was that he was really interested in what was going on—and he was interested in the techniques.”

Paul Hollister’s Gardens of Monticello glass plaque before annealing at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

“[Paul Hollister] was really wrapped up on his panel, and that was innovative in the context of the workshop because nobody made components and fused [them] onto a plate, so Hollister’s panel was attracting a lot of interest because it was a different application for flameworking. It was combining flameworking with fusing as opposed to flameworking with hot glass or flameworking with encapsulating. So Hollister came at it from a different perspective, which was interesting.”

Beadmaking

When workshop attendees were turned loose in the studio following Stankard’s first paperweight-making demonstration, participant Donavon Boutz started creating flameworked glass beads, a technique in which he was well versed. Word of Boutz’s beadmaking spread to students in other sessions, such as those in the concurrent jewelry-making class led by Mary Ann Scherr, and by request, Boutz demonstrated beadmaking to fellow students almost daily. The popularity led Penland to begin offering classes in glass beadmaking from artists like Boutz and others.

Donavon Boutz discusses his father Jean bringing glass in for the Penland workshop.

01:40 Transcript“Everybody was completely new to beadmaking.”

Beadmaking demonstration by Donavon Boutz at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center, Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“Donovan Boutz—he’s responsible truth be told—my workshop gave him a vehicle to promote beadmaking at the torch—flameworked beads. The jewelry people, they got so excited about glass beadmaking that he was invited back the following year under the auspices of jewelry and he set up and made glass beads in the jewelry studio…”

Donavon Boutz beadmaking. Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

01:02

Donavon Boutz’s beadmaking demonstration at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Paul Stankard talks about a woman who still has the beads he gave her from his flameworking workshop.

00:38 Transcript“What’s interesting is, I had my teaching assistant go out and pick field flowers every day or every two days, to put in the studio. So here’s a bouquet that has mountain laurel in it. And I got turned on to mountain laurel and after that workshop, I spent the following five years perfecting the mountain laurel. That was an epiphany for me.”

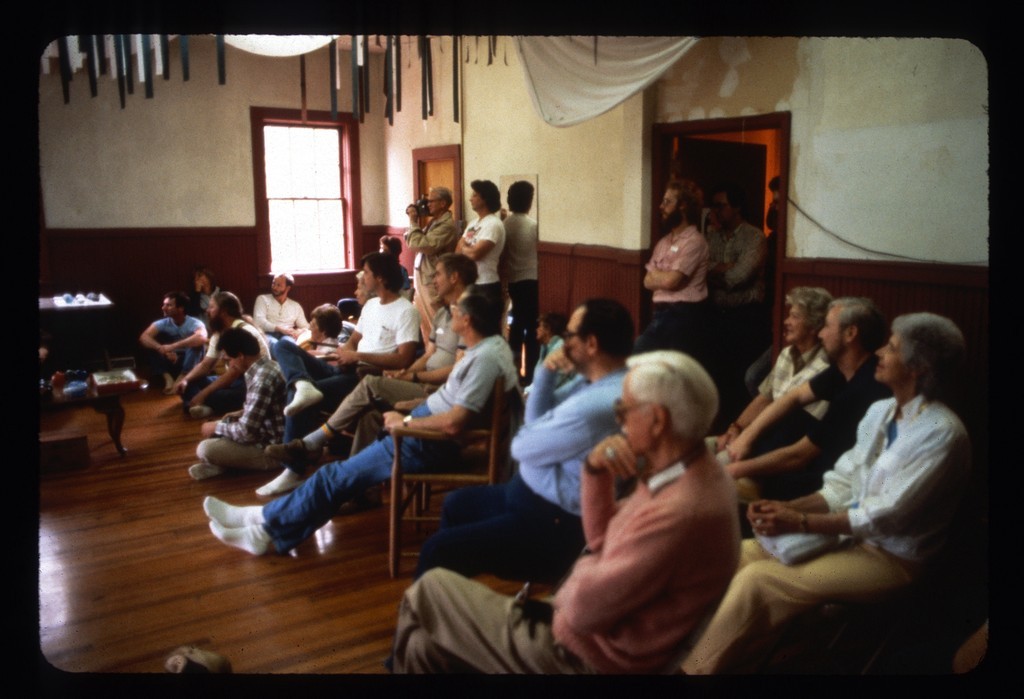

Showing and Telling

Stankard’s workshop was the first dedicated flameworking class offered at Penland. Exceptionally strong interest led Stankard and school administrators to open the course as widely as possible, admitting “standing room only” participants. It was the largest group of students the school had ever had in a single glass session. Stankard treated the workshop like a seminar, inviting attendees to share their own expertise through evening slide shows and discussions. Participants including Paul Hollister, Gary Beecham, Ken Carder, and Geraldine Casper gave presentations. Topics ranged from antique French paperweights to ancient glass. Hollister and Casper already knew each other in a professional capacity, and Casper had consulted Hollister on strategies for expanding the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum’s paperweight collection and developing audience engagement.

Paul Hollister Consultation with Geraldine Casper, March 25, 1974.

Paul Hollister acts as a paperweight consultant for the Begstrom-Mahler Museum of Glass in a recorded conversation with Geraldine Casper.

(Rakow title: Casper [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168410)

Paul Hollister advises Geraldine Casper on paperweight acquisitions for the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum of Glass in 1974.

Audience during “Show and Tell” session at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Ridgeway Building, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection.

Paul Stankard discusses inviting Paul Hollister and Gary Beecham to his Penland flameworking workshop.

01:37 Transcript

Paul Hollister reading “Prescription for the Eye.” Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Videography attributed to Jack Casper. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

02:53

Yaffa Sikorsky-Todd showing her work. Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

01:06

Stephen Dee Edwards discusses sharing in studio glass. Excerpt from “Two Days at Penland.” Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

01:05

Stephen Dee Edwards discusses the expenses Harvey Littleton incurred to run a shop in a 1983 recording by Paul Hollister.

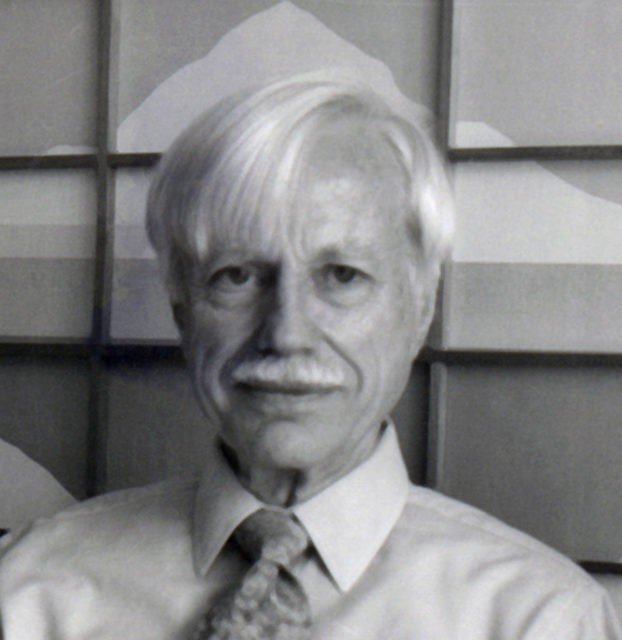

Verne Stanford, then director of the Penland School of Craft. Still from “Two Days at Penland,” a video documenting Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Videography attributed to Jack Casper. Collection of The Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

Gallery of objects made by attendees brought for “Show and Tell” at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“I did an independent reading and research for Warren Moon [1945–1992, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison], and he was one of the world’s foremost people on Attic ceramics and actually made red-figure and black-figure pots. And he thought very highly of vessels. He thought they were a valid art form, as opposed to the rest of the art department who thought they were just craft, and he let me do independent reading and research on ancient glass, and then I presented that to one of his advanced [art history] classes, and he kept a copy of the lecture and used it himself after that. Harvey [Littleton] always encouraged us to look at what has been done before, and I was just in love with some of the ancient pieces, especially some of the Hellenistic pieces, but also Egyptian pieces and pieces made in Mesopotamia. Mainly the lecture was on glass before glassblowing, although there were some pieces that were done with blowing toward the end of the lecture. But it was core vessels and fused vessels—vessels where they made up canes and fused them into vessels. A lot of it you just don’t see—the pieces from the treasure at Canosa—pieces that didn’t involve blowing, they were like fused millefiori platters, and there were two bowls—one fit perfectly over the other, and they had gold foil decoration in between. You know, incredibly sophisticated work.”

Paul Stankard and Gary Beecham at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Paul Stankard discusses Gary Beecham’s lecture at his Penland flameworking workshop.

00:51 TranscriptPaul Hollister Interview with Gary Beecham, November 14, 1981.

Paul Hollister interviews Gary Beecham in Hollister’s apartment.

(Rakow title: Gary Beecham interview [sound recording] / with Paul Hollister, BIB ID: 168599)

In a 1981 interview with Paul Hollister, Gary Beecham discusses his “quilt pattern” pieces, creating work at Lobmeyr and Penland, building ovens, and making his own glass.

Building Community

Penland students connect with fellow artists outside the classroom through organized excursions to nearby independent studios and socializing after hours. Participants in Stankard’s workshop took field trips to visit local glass artists and continued to work at night in a more relaxed social atmosphere.

Field Trips

Although Stankard recalls that days were so packed with activity that the group only had time for limited outings, the workshop included field trips. An image—likely taken by Hollister himself—shows Stankard and many of the workshop attendees at local artist Robert Levin’s studio. Outings to nearby studios are common at Penland School, with a large concentration of makers in the area. Many, like Levin, took part in Penland’s residency programs prior to making western North Carolina their home.

Stankard remembers taking his flameworking students on a trip to Spruce Pine Batch Company, the glass batch manufactory that Harvey Littleton founded after he retired from teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and moved to North Carolina. Littleton also established a large studio with a printing facility that was used by other local artists. Several of Stankard’s workshop participants, including Ken Carder and Gary Beecham, worked for Littleton. Littleton’s son John and daughter-in-law, Kate Vogel, became active artists in the community, and his son Tom took over Spruce Pine Batch.

Group portrait in front of Robert Levin’s studio, including Paul Stankard and a number of attendees from his 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Burnsville, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

Robert Levin talks about Penland classes coming to visit his and other artists’ studios.

02:03 TranscriptRobert Levin talks about the supportive environment of Penland through the residency program.

01:40 TranscriptKate Vogel and John Littleton talk about Bill Brown’s artists’ residency program and how it led to artists buying homes in the area.

01:03 Transcript“It’s still a very kind of uncompetitive…genial group. There’s definitely more studios in the area, and that’s good. It kind of snowballs a little bit, because people come to work with someone who has a studio, and then sometimes that person that’s working with them will go out and start their own studio in the area. So I think that’s happened more and more.”

Kate Vogel and John Littleton talk about Bill Brown’s artists’ residency program and how it led to artists buying homes in the area.

01:03 Transcript

After Hours

After long, intense days in the studio, workshop participants relaxed at night. They converted a demo room into dancing space, turned up the music, and made beer runs to the next county, as it was illegal to buy or sell alcohol in Penland’s Mitchell County at the time. Students continued working far into the night making jewelry, beads, and other objects.

After-hours group photo at Paul Stankard’s 1986 Flameworking Workshop, Bonnie Willis Ford Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, formerly Penland School of Crafts, Penland, North Carolina. Bard Graduate Center Paul Hollister Slide Collection. Photo attributed to Paul Hollister.

“And at night everything was ‘kick back and drink beer and dance’. The constant song that was playing was Marvin Gaye[’s] ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine’—so that was blasting in the studio, and people were dancing, and to this day, whenever I hear that song, I’m transported back to Penland.”

Penland: 21st Century

Glass, new to Penland in the 1960s, is now a standard medium in the school’s curriculum, and glass artists from throughout the United States and the world have come to teach and to learn at Penland. Its current glass studio uses Spruce Pine Batch and has three furnaces, ten dedicated flameworking stations, and a cold shop. Named the Bill Brown Glass Studio after the director who brought glass to Penland, it was dedicated in 1995 during a meeting of the Glass Art Society, the organization Mark Peiser cofounded at Penland 24 years earlier. The school remains a vital resource for learning glassworking and other craft skills.

Metals Studio, Penland School of Craft, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft. Photo: Robin Dryer.

Glass Studio, Penland School of Craft, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft. Photo: Robin Dryer.

Blacksmith Studio, Penland School of Craft, Penland, North Carolina. Image courtesy of the Jane Kessler Memorial Archives at the Penland School of Craft. Photo: Robin Dryer.