Sèvres Antislavery Medallion

In the spring of 1789, the Sèvres Manufactory created a medallion that communicated a powerful antislavery message. It was inspired by a similar medallion produced by British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) just two years earlier. Wedgwood’s version became a popular icon of the antislavery movement in the English-speaking world, displayed by thousands of abolitionists. Yet production of the Sèvres medallion was halted after only fifteen objects were completed due to fears that it would lead to insurrections amongst enslaved people in France’s colonies.

Sèvres Antislavery Medallion

In the spring of 1789, the Sèvres Manufactory created a medallion that communicated a powerful antislavery message. It was inspired by a similar medallion produced by British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) just two years earlier. Wedgwood’s version became a popular icon of the antislavery movement in the English-speaking world, displayed by thousands of abolitionists. Yet production of the Sèvres medallion was halted after only fifteen objects were completed due to fears that it would lead to insurrections amongst enslaved people in France’s colonies.

The History of the Medallion

There are clear similarities between the Sèvres antislavery medallion, made under the direction of Louis-Simon Boizot in 1789, and British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood’s version, which was designed by sculptor Henry Webber (1754–1826) and modeler William Hackwood (d. 1836) in 1787. Both feature the figure of an enslaved Black man on bended knee, his hands and feet bound with chains and his arms raised in a gesture of supplication. As with many depictions of enslaved people at this time, he is presented as subservient. Arching above each figure, in raised letters, a question appears. The Wedgwood medallion reads in English: “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” The Sèvres version reads in French: “Ne suis-je pas un homme? Un frère?.”

But the two medallions are not identical. In addition to the language of the text and the differences in the way the central figure is rendered, the British and French objects differ in size, shape, and material. The Sèvres medallion is circular and about the size of a coffee cup, whereas Wedgwood’s version is oval and much smaller. Each is crafted from materials emblematic of their respective manufactories: the Sèvres medallion was made in white and black hard-paste porcelain biscuit; the Wedgwood medallion was most commonly produced in jasperware, a kind of unglazed stoneware invented by Wedgwood in the early 1770s.

In 1787 the Wedgwood medallion was adopted as the official seal of the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, of which Wedgwood was a prominent member. Thousands were distributed for free at the Society’s meetings in Britain and the United States, and abolitionists proudly wore their Wedgwood medallions as a demonstration of their antislavery beliefs. The fifteen Sèvres antislavery medallions that were made in 1789 were never distributed, and of these only two remain accounted for, one held by the Musée National Adrien Dubouché, in Limoges, and the other by Princeton University Art Museum.

1789

Inscription: “NE SUIS-JE PAS UN HOMME? UN FRERE?” [AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?] Hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

3 3/8 × 1/4 inches (8.6 × 0.6 cm)

Princeton University Art Museum, Trumbull-Prime Collection (y931)

1834–35

Inscription: “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER”

White Jasper with a black relief

1 1/4 × 1 1/8 × 1/16 inches (3.2 × 2.9 × 0.2 cm)

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.11.1

The History of the Medallion

Click for a closer view of this object.

Antislavery medallion

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1789

Inscription: “NE SUIS-JE PAS UN HOMME? UN FRERE?” [AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?]

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

3 3/8 × 1/4 inches (8.6 × 0.6 cm)

Princeton University Art Museum, Trumbull-Prime Collection, y931

There are clear similarities between the Sèvres antislavery medallion, made under the direction of Louis-Simon Boizot in 1789, and British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood’s version, which was designed by sculptor Henry Webber (1754–1826) and modeler William Hackwood (d. 1836) in 1787. Both feature the figure of an enslaved Black man on bended knee, his hands and feet bound with chains and his arms raised in a gesture of supplication. As with many depictions of enslaved people at this time, he is presented as subservient. Arching above each figure, in raised letters, a question appears. The Wedgwood medallion reads in English: “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” The Sèvres version reads in French: “Ne suis-je pas un homme? Un frère?.”

But the two medallions are not identical. In addition to the language of the text and the differences in the way the central figure is rendered, the British and French objects differ in size, shape, and material. The Sèvres medallion is circular and about the size of a coffee cup, whereas Wedgwood’s version is oval and much smaller. Each is crafted from materials emblematic of their respective manufactories: the Sèvres medallion was made in white and black hard-paste porcelain biscuit; the Wedgwood medallion was most commonly produced in jasperware, a kind of unglazed stoneware invented by Wedgwood in the early 1770s.

In 1787 the Wedgwood medallion was adopted as the official seal of the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, of which Wedgwood was a prominent member. Thousands were distributed for free at the Society’s meetings in Britain and the United States, and abolitionists proudly wore their Wedgwood medallions as a demonstration of their antislavery beliefs. The fifteen Sèvres antislavery medallions that were made in 1789 were never distributed, and of these only two remain accounted for, one held by the Musée National Adrien Dubouché, in Limoges, and the other by Princeton University Art Museum.

William Hackwood (modeler)

Medallion produced for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, Ltd.

1787–90

Inscription: “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER”

White Jasper with a black relief

1 1/4 × 1 1/8 × 1/16 inches (3.2 × 2.9 × 0.2 cm)

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.11.1

Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier aîné (modeler)

Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, (Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen)

1789

Oil on wood

27 15/16 × 22 1/16 inches (71 × 56 cm)

Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, P809

CCØ Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

Antislavery Movements During the French Revolution

During the 1780s, France’s transatlantic trade in enslaved human beings was at its peak. Wealth produced in French plantation colonies, including Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Guiana, was felt by many pro-slavery advocates to be essential to the flailing French economy. In Saint-Domingue alone, over 500,000 enslaved Africans were brutally exploited to produce sugar, cotton, indigo, and coffee for Europeans, making this island the most profitable colony on earth.

French antislavery movements were also building in strength during this period. One of the most prominent was the Société des Amis des Noirs, which adapted many of its arguments and materials from the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, including the image made famous by Wedgwood’s antislavery medallion. As the French Revolution took hold, many abolitionists argued that the institution of slavery was incompatible with France’s new ideals. They pointed to the National Constituent Assembly’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, which proclaimed: “all men are born free and remain free in equal rights.”

By 1789, the first year of the French Revolution, fears of rebellions in France’s colonies were intensifying, fed by the growing popularity of abolitionism in Britain and the United States, and France’s own political upheavals. These fears were warranted. In 1791, just two years later, enslaved people in Saint-Domingue did rise up against their oppressors, instigating the Haitian Revolution. Slavery was abolished in France and its colonies in 1794. However, it was reinstated in 1802 by order of Napoléon Bonaparte, except in Haiti, which became an independent republic in 1804.

Antislavery Movements During the French Revolution

During the 1780s, France’s transatlantic trade in enslaved human beings was at its peak. Wealth produced in French plantation colonies, including Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Guiana, was felt by many pro-slavery advocates to be essential to the flailing French economy. In Saint-Domingue alone, over 500,000 enslaved Africans were brutally exploited to produce sugar, cotton, indigo, and coffee for Europeans, making this island the most profitable colony on earth.

French antislavery movements were also building in strength during this period. One of the most prominent was the Société des Amis des Noirs, which adapted many of its arguments and materials from the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, including the image made famous by Wedgwood’s antislavery medallion. As the French Revolution took hold, many abolitionists argued that the institution of slavery was incompatible with France’s new ideals. They pointed to the National Constituent Assembly’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, which proclaimed: “all men are born free and remain free in equal rights.”

By 1789, the first year of the French Revolution, fears of rebellions in France’s colonies were intensifying, fed by the growing popularity of abolitionism in Britain and the United States, and France’s own political upheavals. These fears were warranted. In 1791, just two years later, enslaved people in Saint-Domingue did rise up against their oppressors, instigating the Haitian Revolution. Slavery was abolished in France and its colonies in 1794. However, it was reinstated in 1802 by order of Napoléon Bonaparte, except in Haiti, which became an independent republic in 1804.

Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier aîné (modeler)

Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, (Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen)

1789

Oil on wood

27 15/16 × 22 1/16 inches (71 × 56 cm)

Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, P809

CCØ Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

Why This Medallion Was Never Distributed

Fearing that the medallion would inspire a violent rebellion amongst enslaved people, the administrators of France’s plantation colonies demanded that Sèvres, which was under the control of the French state, immediately cease its production. We know this because of an April 8, 1789, letter addressed to Antoine Régnier, then director of Sèvres, written by Jean de Montucla at the direction of the comte d’Angiviller, who oversaw all state manufactories:

Monsieur le Comte d’Angiviller instructs me to write to you with the utmost urgency on the following subject. He has been informed that someone has requested from the manufactory the production of medals with a white ground showing a Black man on his knees and enchained with the inscription “Am I not a man, am I not your brother?” No doubt the intention is good, and indeed dictated by humane impulses, but similar medals exported to the colonies could be seen by Black peoples and instigate an uprising. Monsieur le Comte instructs me to warn you that he categorically forbids any continuation of this project, and, if the medal has already been made, to deliver not a single one. This demand is made by the colonial administrative authorities, and it is impossible to refuse them. Finally, Monsieur le Comte instructs me to request that a response be addressed directly to him on this matter. Judge for yourself the danger that would be incurred if these medals should reach our colonies. In several English colonies where people have been advised that the English parliament was concerning itself with freedom for Black peoples, they promptly rebelled in various settlements, and these rebellions do not happen without every white being massacred.

Despite Régnier’s agreement to halt production of the antislavery medallion at Sèvres as requested in this letter, a successful uprising of enslaved people began just two years later, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which in 1804 proclaimed its independence from France as the sovereign nation of Haiti.

Why This Medallion Was Never Distributed

Fearing that the medallion would inspire a violent rebellion amongst enslaved people, the administrators of France’s plantation colonies demanded that Sèvres, which was under the control of the French state, immediately cease its production. We know this because of an April 8, 1789, letter addressed to Antoine Régnier, then director of Sèvres, written by Jean de Montucla at the direction of the comte d’Angiviller, who oversaw all state manufactories:

Monsieur le Comte d’Angiviller instructs me to write to you with the utmost urgency on the following subject. He has been informed that someone has requested from the manufactory the production of medals with a white ground showing a Black man on his knees and enchained with the inscription “Am I not a man, am I not your brother?” No doubt the intention is good, and indeed dictated by humane impulses, but similar medals exported to the colonies could be seen by Black peoples and instigate an uprising. Monsieur le Comte instructs me to warn you that he categorically forbids any continuation of this project, and, if the medal has already been made, to deliver not a single one. This demand is made by the colonial administrative authorities, and it is impossible to refuse them. Finally, Monsieur le Comte instructs me to request that a response be addressed directly to him on this matter. Judge for yourself the danger that would be incurred if these medals should reach our colonies. In several English colonies where people have been advised that the English parliament was concerning itself with freedom for Black peoples, they promptly rebelled in various settlements, and these rebellions do not happen without every white being massacred.

Despite Régnier’s agreement to halt production of the antislavery medallion at Sèvres as requested in this letter, a successful uprising of enslaved people began just two years later, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which in 1804 proclaimed its independence from France as the sovereign nation of Haiti.

Letter written by Jean de Montucla at the direction of the comte d’Angiviller

April 8, 1789

Ink on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres

Letter written by Jean de Montucla at the direction of the comte d’Angiviller

April 8, 1789

Ink on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres

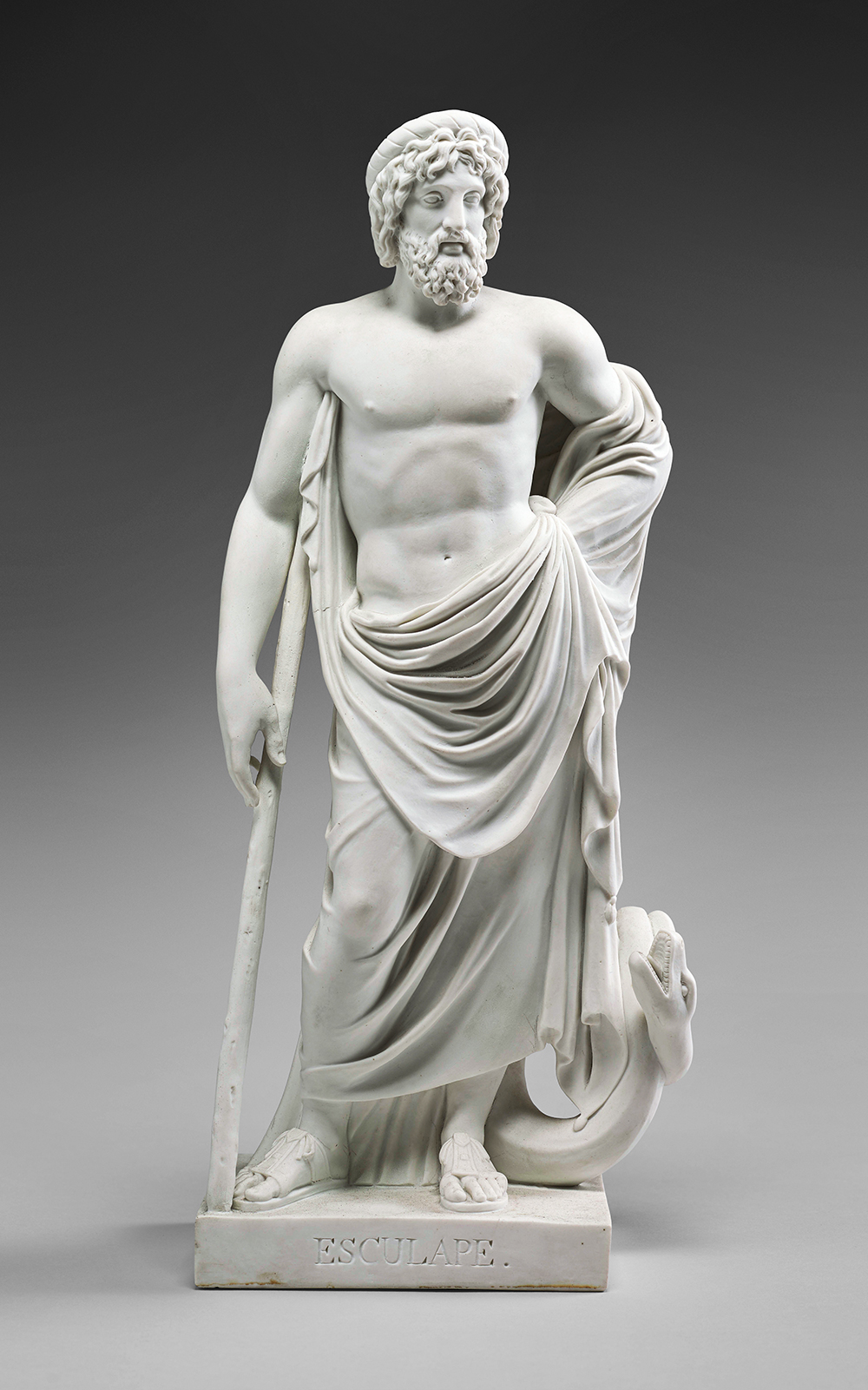

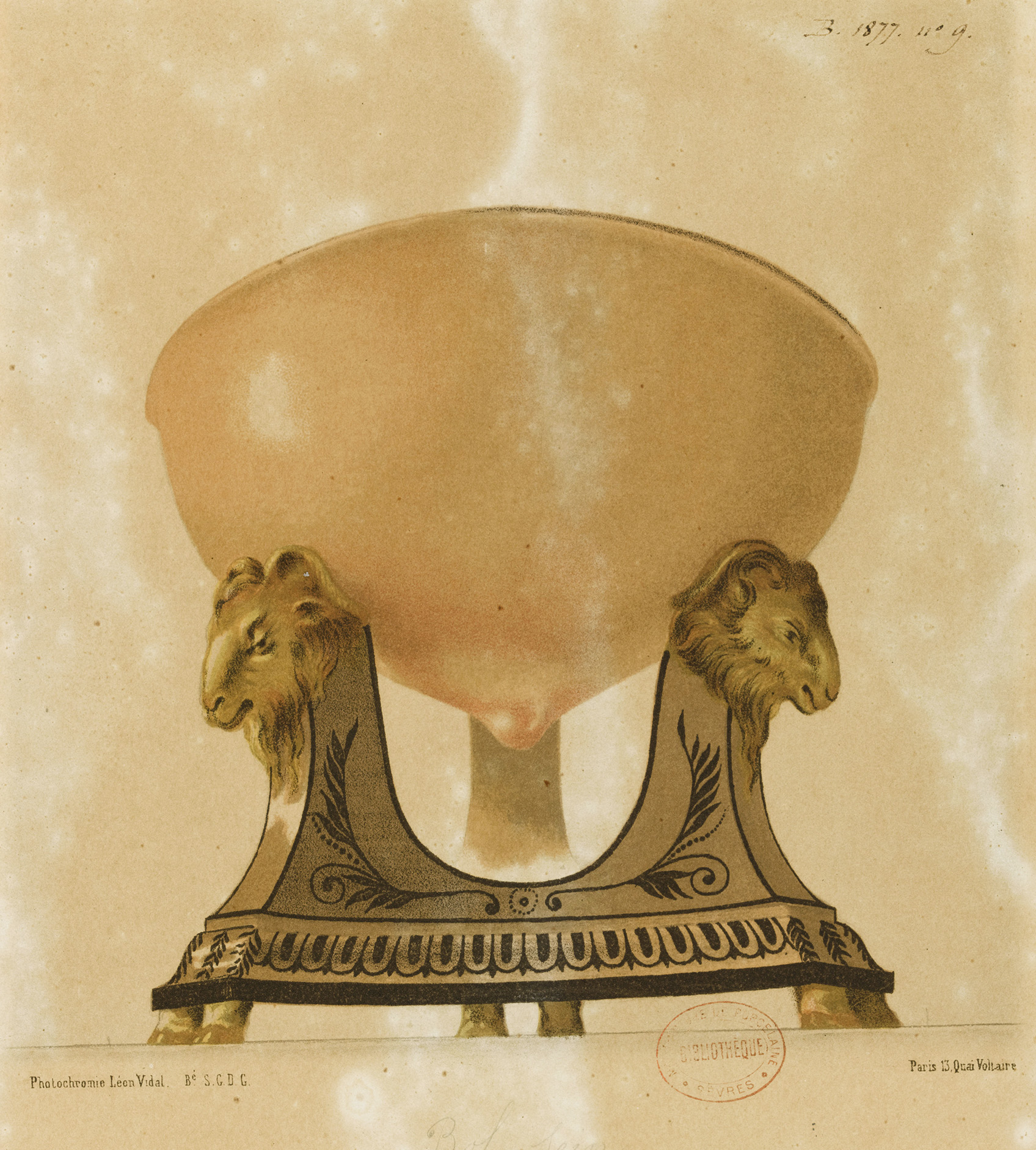

Antislavery Objects at Sèvres

Louis-Simon Boizot, under whose direction the Sèvres antislavery medallion was made, was head artist in charge of sculpture at Sèvres during the French Revolution. This was a difficult time for the manufactory: in addition to severe financial pressures, the character of the French state changed dramatically several times between 1789, when the Revolution began, and 1804, when Napoléon I was crowned emperor. Nevertheless, the work of designing and executing sculpture continued, with smaller objects such as medallions and busts dominating production. While Boizot’s personal involvement with abolitionism is unclear, given the popularity of the Wedgwood antislavery medallion in Britain, the production of a similar object at Sèvres likely seemed a sound idea in 1789.

In 1794, following the revolution in Haiti and the abolition of slavery in France and its colonies, abolitionism was on firmer footing in France. In that year, Boizot created designs for two more allegorical sculptures conveying antislavery ideals. The first, La Nature, depicts a woman nursing two babies; one infant appears European, the other African. The second, Les Noirs libre, depicts a freed African man and woman. The man wears a Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty adopted during the French Revolution, and the woman a set square, a masonic symbol of equality shaped like a triangle. Both were produced in white biscuit.

Neither of these sculptures sold well, and once Napoléon Bonaparte reinstituted slavery within France and its colonies in 1802, there was no question of continuing their production. The Phrygian cap featured on the male figure of Les Noirs libre reappeared on another, much later, allegory of the Republic, Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse’s bust of La République.

Antislavery Objects at Sèvres

Louis-Simon Boizot, under whose direction the Sèvres antislavery medallion was made, was head artist in charge of sculpture at Sèvres during the French Revolution. This was a difficult time for the manufactory: in addition to severe financial pressures, the character of the French state changed dramatically several times between 1789, when the Revolution began, and 1804, when Napoléon I was crowned emperor. Nevertheless, the work of designing and executing sculpture continued, with smaller objects such as medallions and busts dominating production. While Boizot’s personal involvement with abolitionism is unclear, given the popularity of the Wedgwood antislavery medallion in Britain, the production of a similar object at Sèvres likely seemed a sound idea in 1789.

In 1794, following the revolution in Haiti and the abolition of slavery in France and its colonies, abolitionism was on firmer footing in France. In that year, Boizot created designs for two more allegorical sculptures conveying antislavery ideals. The first, La Nature, depicts a woman nursing two babies; one infant appears European, the other African. The second, Les Noirs libre, depicts a freed African man and woman. The man wears a Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty adopted during the French Revolution, and the woman a set square, a masonic symbol of equality shaped like a triangle. Both were produced in white biscuit.

Neither of these sculptures sold well, and once Napoléon Bonaparte reinstituted slavery within France and its colonies in 1802, there was no question of continuing their production. The Phrygian cap featured on the male figure of Les Noirs libre reappeared on another, much later, allegory of the Republic, Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse’s bust of La République.

Louis-Simon Boizot

La Nature

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1794

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

9 5/8 × 8 1/4 × 7 1/16 inches (24.5 × 21 × 18 cm)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, C.361-2009

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Louis-Simon Boizot

La Nature

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1794

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

9 5/8 × 8 1/4 × 7 1/16 inches (24.5 × 21 × 18 cm)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, C.361-2009

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Louis-Simon Boizot

Les Noirs libres (Group of a Free Man and Woman)

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1794

Inscription: MOI ÉGALE À TOI, MOI LIBRE AUSSI

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

8 5/8 × 6 1/8 × 5 3/8 inches (22 × 15.5 × 13.7 cm)

© Musées d’Art et d’Histoire de La Rochelle, 1983.4.2

© Max Roy

Louis-Simon Boizot

Les Noirs libres (Group of a Free Man and Woman)

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1794

Inscription: MOI ÉGALE À TOI, MOI LIBRE AUSSI

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

8 5/8 × 6 1/8 × 5 3/8 inches (22 × 15.5 × 13.7 cm)

© Musées d’Art et d’Histoire de La Rochelle, 1983.4.2

© Max Roy