Materials

&

Production

Throughout the long history of Sèvres, progress in techniques, innovations in materials, and stylistic evolutions have always gone hand in hand. Among the many examples, hard-paste porcelain allowed larger dimensions at a time when the manufactory had to prove its superiority over its rivals; grand coulage (large slip-casting) opened the way for complex pieces that required less repair work; atmosphere control during firing improved the appearance of porcelain; and the temporary adoption of faience and glazed pottery also accompanied developments in color.

Despite these many changes, production methods for porcelain sculpture have remained almost constant over the years at Sèvres. Each of the complex, interconnected steps performed by artisans and workers at the manufactory influences the final appearance of every example of sculpture produced. Thus, even when a mold is used, each piece is always unique.

Materials & Production

The technique for making a sculpture at the Sèvres Manufactory remains unchanged since the eighteenth century. Everything starts with a drawing or a three-dimensional sketch in clay. From this, a plaster model of the intended piece is made.

As raw porcelain paste is fragile, it is necessary to cut the plaster model into smaller, more easily manipulated parts. For each of these, a plaster mold, which consists of two halves, is created. The group of molds necessary for executing a sculpture is called a “ronde de moules” (round of molds). For the largest and most complex sculptures, the “round” could include one hundred molds or more.

Once the molds are ready, the sculptor fills them with raw paste, spread in an even layer, carefully pressing this paste into every crevice. After the mold is closed, the plaster rapidly absorbs some of the moisture from the paste, which then retracts and allows the removal of the molded piece. Once all the parts are molded, the sculptor reconstructs the composition, using the plaster model as a guide to ensure every piece is placed correctly. With all the parts reunited, the “seams” caused by their joining are retouched and the details sharpened. Finally, freely modeled ornaments, such as flowers or fruits, can be added to complete the decoration.

Throughout the long history of Sèvres, progress in techniques, innovations in materials, and stylistic evolutions have always gone hand in hand. Among the many examples, hard-paste porcelain allowed larger dimensions at a time when the manufactory had to prove its superiority over its rivals; grand coulage (large slip-casting) opened the way for complex pieces that required less repair work; atmosphere control during firing improved the appearance of porcelain; and the temporary adoption of faience and glazed pottery also accompanied developments in color.

Despite these many changes, production methods for porcelain sculpture have remained almost constant over the years at Sèvres. Each of the complex, interconnected steps performed by artisans and workers at the manufactory influences the final appearance of every example of sculpture produced. Thus, even when a mold is used, each piece is always unique.

Technique

The technique for making a sculpture at the Sèvres Manufactory has remained unchanged since the eighteenth century. Everything starts with a drawing or a three-dimensional sketch in clay. From this, a plaster model of the intended piece is made.

As raw porcelain paste is fragile, it is necessary to cut the plaster model into smaller, more easily manipulated parts. For each of these, a plaster mold, which consists of two halves, is created. The group of molds necessary for executing a sculpture is called a ronde de moules (round of molds). For the largest and most complex sculptures, the “round” could include one hundred molds or more.

Once the molds are ready, the sculptor fills them with raw paste, spread in an even layer, carefully pressing this paste into every crevice. After the mold is closed, the plaster rapidly absorbs some of the moisture from the paste, which then retracts and allows the removal of the molded piece. Once all the parts are molded, the sculptor reconstructs the composition, using the plaster model as a guide to ensure every piece is placed correctly. With all the parts reunited, the “seams” caused by their joining are retouched and the details sharpened. Finally, freely modeled ornaments, such as flowers or fruits, can be added to complete the decoration.

The technique for making a sculpture at the Sèvres Manufactory has remained unchanged since the eighteenth century. Everything starts with a drawing or a three-dimensional sketch in clay. From this, a plaster model of the intended piece is made.

As raw porcelain paste is fragile, it is necessary to cut the plaster model into smaller, more easily manipulated parts. For each of these, a plaster mold, which consists of two halves, is created. The group of molds necessary for executing a sculpture is called a ronde de moules (round of molds). For the largest and most complex sculptures, the “round” could include one hundred molds or more.

Once the molds are ready, the sculptor fills them with raw paste, spread in an even layer, carefully pressing this paste into every crevice. After the mold is closed, the plaster rapidly absorbs some of the moisture from the paste, which then retracts and allows the removal of the molded piece. Once all the parts are molded, the sculptor reconstructs the composition, using the plaster model as a guide to ensure every piece is placed correctly. With all the parts reunited, the “seams” caused by their joining are retouched and the details sharpened. Finally, freely modeled ornaments, such as flowers or fruits, can be added to complete the decoration.

Biscuits

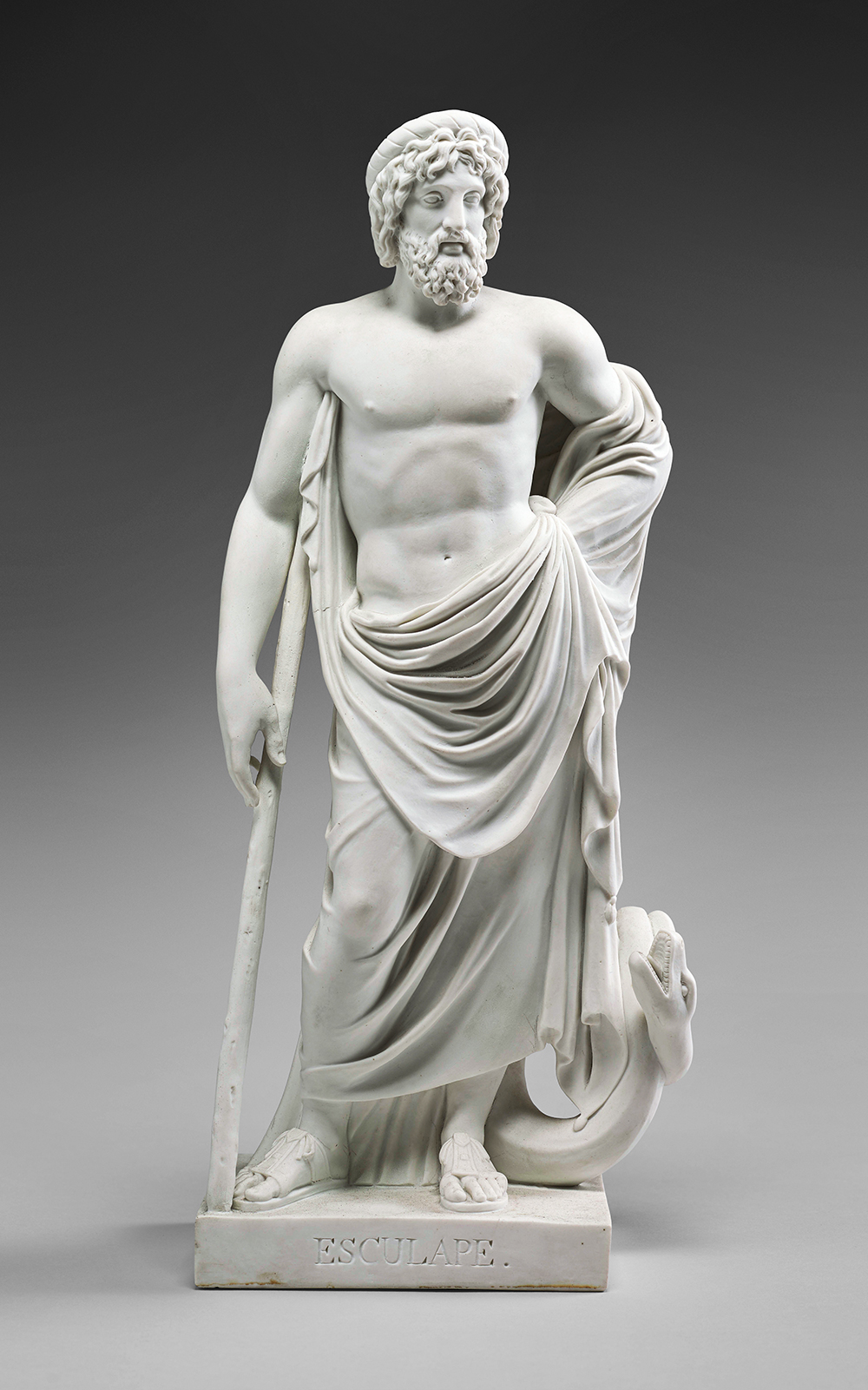

In 1751 the Vincennes Manufactory hired Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), a painter from the Académie Royale (the exclusive institution that oversaw French painting and sculpture), to supervise its decoration workshop and the production of sculptures. Bachelier made the radical decision to leave all sculptures in “biscuit” condition—unpainted and unglazed. In doing so, he distinguished the manufactory from its European rivals, who continued to produce enameled or colored figurines.

In addition to resembling Chinese porcelain figurines, which were highly coveted by collectors at the time, biscuit offered several advantages. Like marble, the material’s white surface subtly reflected light. Thick, haphazardly applied glazes obscured delicate sculpted details; without these glazes, biscuits only required two firings, which saved time and resources. Bachelier’s innovation also coincided with a moment when porcelain figurines began to adorn dessert tables. To create a pleasing tablescape, it was preferable that the various elements of a centerpiece be similar in dimension, quality, and decoration—an effect easier to attain in monochrome white.

Over the years, the production of biscuit sculptures at Sèvres has evolved from Rococo pastoral scenes after designs by the painter François Boucher (1703–1770) to elegant Neoclassical groups and figures after models by the sculptors Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809). Today, biscuit is still a signature of the manufactory, corresponding to the minimalist aesthetics of contemporary design.

In 1751 the Vincennes Manufactory hired Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), a painter from the Académie Royale (the exclusive institution that oversaw French painting and sculpture), to supervise its decoration workshop and the production of sculptures. Bachelier made the radical decision to leave all sculptures in “biscuit” condition—unpainted and unglazed. In doing so, he distinguished the manufactory from its European rivals, who continued to produce enameled or colored figurines.

In addition to resembling Chinese porcelain figurines, which were highly coveted by collectors at the time, biscuit offered several advantages. Like marble, the material’s white surface subtly reflected light. Thick, haphazardly applied glazes obscured delicate sculpted details; without these glazes, biscuits only required two firings, which saved time and resources. Bachelier’s innovation also coincided with a moment when porcelain figurines began to adorn dessert tables. To create a pleasing tablescape, it was preferable that the various elements of a centerpiece be similar in dimension, quality, and decoration—an effect easier to attain in monochrome white.

Over the years, the production of biscuit sculptures at Sèvres has evolved from Rococo pastoral scenes after designs by the painter François Boucher (1703–1770) to elegant Neoclassical groups and figures after models by the sculptors Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809). Today, biscuit is still a signature of the manufactory, corresponding to the minimalist aesthetics of contemporary design.

In 1751 the Vincennes Manufactory hired Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), a painter from the Académie Royale (the exclusive institution that oversaw French painting and sculpture), to supervise its decoration workshop and the production of sculptures. Bachelier made the radical decision to leave all sculptures in “biscuit” condition—unpainted and unglazed. In doing so, he distinguished the manufactory from its European rivals, who continued to produce enameled or colored figurines.

In addition to resembling Chinese porcelain figurines, which were highly coveted by collectors at the time, biscuit offered several advantages. Like marble, the material’s white surface subtly reflected light. Thick, haphazardly applied glazes obscured delicate sculpted details; without these glazes, biscuits only required two firings, which saved time and resources. Bachelier’s innovation also coincided with a moment when porcelain figurines began to adorn dessert tables. To create a pleasing tablescape, it was preferable that the various elements of a centerpiece be similar in dimension, quality, and decoration—an effect easier to attain in monochrome white.

Over the years, the production of biscuit sculptures at Sèvres has evolved from Rococo pastoral scenes after designs by the painter François Boucher (1703–1770) to elegant Neoclassical groups and figures after models by the sculptors Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809). Today, biscuit is still a signature of the manufactory, corresponding to the minimalist aesthetics of contemporary design.

Vase Mousse roulée Médicis (Medici Rolled Foam Vase)

Christian Renonciat (b. 1947), a philosopher-turned-sculptor, created this “rolled foam” vase for Sèvres in 1983. It radically reinterprets the antique krater shape of the famous Medici Vase, a form made at the manufactory since the eighteenth century.

While it mimics the appearance of packing foam, especially its spongy plasticity, the Medici Rolled Foam Vase is made from pâte Antoine d’Albis (PAA), developed at Sèvres in 1965. This innovative paste utilizes a newly discovered source of kaolin, the white clay essential to the production of hard-paste porcelain. The vase’s interior exhibits the low luster of another Sèvres invention from this period, a white semimatte glaze. The subtle interplay between the unglazed exterior and the glaze of the interior shows the potential of porcelain in the hands of this materials-based artist as he continues the tradition of unglazed biscuit sculpture at Sèvres.

Christian Renonciat (b. 1947), a philosopher-turned-sculptor, created this “rolled foam” vase for Sèvres in 1983. It radically reinterprets the antique krater shape of the famous Medici Vase, a form made at the manufactory since the eighteenth century.

While it mimics the appearance of packing foam, especially its spongy plasticity, the Medici Rolled Foam Vase is made from pâte Antoine d’Albis (PAA), developed at Sèvres in 1965. This innovative paste utilizes a newly discovered source of kaolin, the white clay essential to the production of hard-paste porcelain. The vase’s interior exhibits the low luster of another Sèvres invention from this period, a white semimatte glaze. The subtle interplay between the unglazed exterior and the glaze of the interior shows the potential of porcelain in the hands of this materials-based artist as he continues the tradition of unglazed biscuit sculpture at Sèvres.

PAA porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2013.D.11612

© 2024 Christian Renonciat / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

PAA porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2013.D.11612

Charcoal on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2015.D.231

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Charcoal on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2015.D.231

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

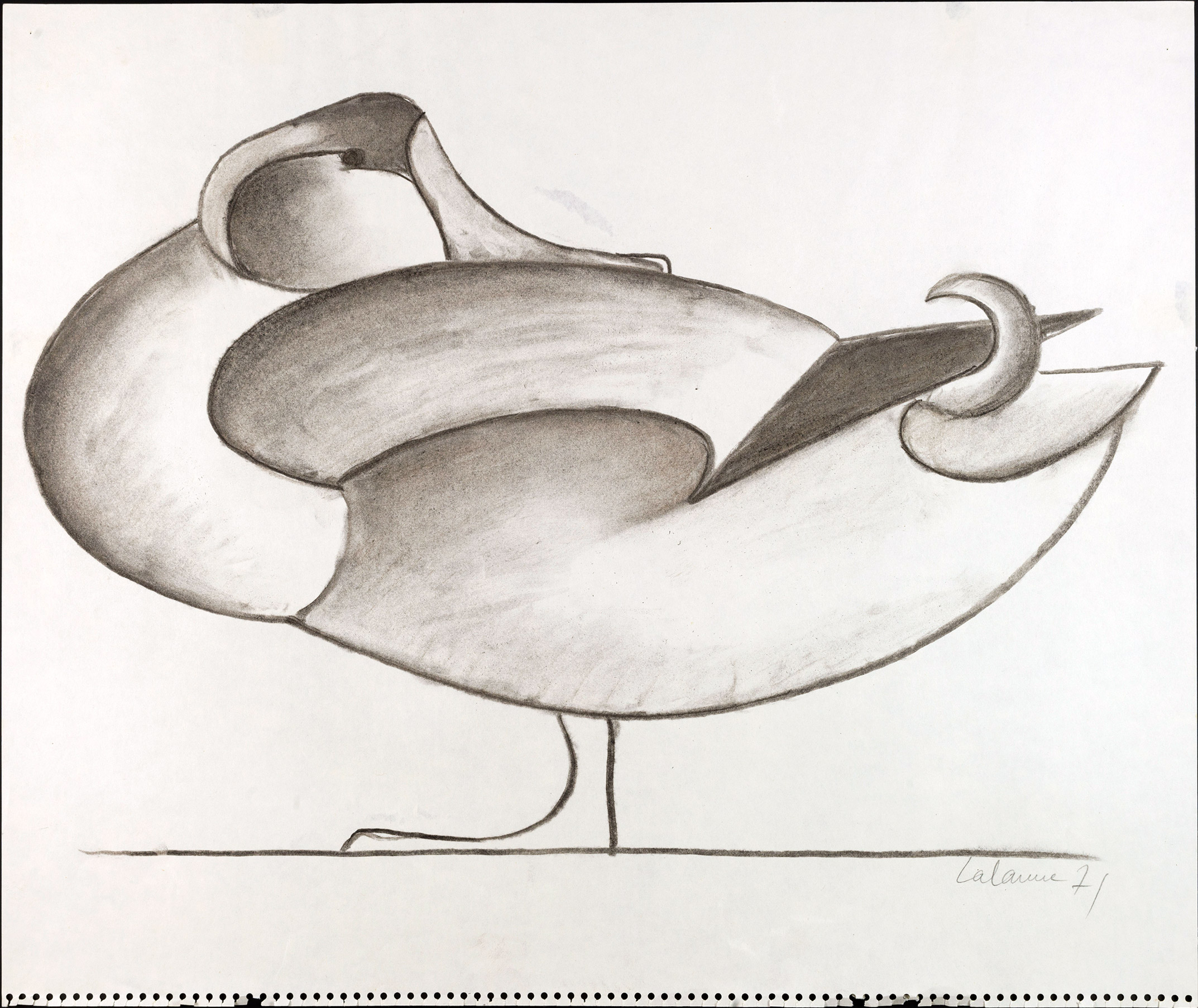

Canard aux nénuphars (Duck with Water Lilies)

The famed French designer François-Xavier Lalanne (1927–2008) collaborated with the manufactory from 1966 to 1979 and created composite works made with biscuit pâte nouvelle porcelain and metal parts supplied by his studio. This Duck with Water Lilies centerpiece, originally made in 1972, was enlarged six years later to include candlesticks adorned with porcelain flowers. Twenty-four examples were made between 1978 and 1982, one of which was acquired by Georges Pompidou, then president of France, for his personal collection. Others made their way to the Elysée Palace or to French embassies abroad, including one to Washington, DC.

The famed French designer François-Xavier Lalanne (1927–2008) collaborated with the manufactory from 1966 to 1979 and created composite works made with biscuit pâte nouvelle porcelain and metal parts supplied by his studio. This Duck with Water Lilies centerpiece, originally made in 1972, was enlarged six years later to include candlesticks adorned with porcelain flowers. Twenty-four examples were made between 1978 and 1982, one of which was acquired by Georges Pompidou, then president of France, for his personal collection. Others made their way to the Elysée Palace or to French embassies abroad, including one to Washington, DC.

Pâte nouvelle porcelain biscuit and nickel silver

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 25432

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Charcoal on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2015.D.231

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Pâte nouvelle porcelain biscuit and nickel silver

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 25432

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Pastes at Sèvres

During the first thirty years of its history, the Vincennes-Sèvres factory exclusively produced “soft-paste” porcelain, made from marl (a refined clay) mixed with powdered glass, lead oxide, and chalk to mimic East Asian porcelain. True “hard-paste” porcelain, which was invented and perfected in ancient China, was greatly desired in Europe for its pure whiteness, translucency, imperviousness to water, resistance to temperature, and the characteristic bell-like sound it makes when gently struck. Only once its key ingredient, a white clay called kaolin, was discovered near Limoges in 1768 could hard-paste porcelain be produced in France. Sèvres immediately adopted this superior material and its director Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847) decided to cease production of soft-paste porcelain and focus exclusively on the new formula in 1801.

Over the next two centuries, the range of materials used at Sèvres expanded even further to encompass many different kinds of ceramics, including grès cérame (stoneware) and faience (a kind of tin-glazed earthenware). Currently, the manufactory uses five different porcelain pastes: pâte tendre (soft paste); pâte dure (hard paste); pâte nouvelle (a “new paste” invented at Sèvres around 1884); pâte Antoine d’Albis (also called PAA, developed at Sèvres in 1965 after the discovery of new kaolin deposits and named for the head of the laboratory); and a new soft-paste porcelain (developed by d’Albis in 1977) that is similar to English bone china. Each new innovation in materials was a direct response to the aesthetic, technological, and economic challenges of its era.

During the first thirty years of its history, the Vincennes-Sèvres factory exclusively produced “soft-paste” porcelain, made from marl (a refined clay) mixed with powdered glass, lead oxide, and chalk to mimic East Asian porcelain. True “hard-paste” porcelain, which was invented and perfected in ancient China, was greatly desired in Europe for its pure whiteness, translucency, imperviousness to water, resistance to temperature, and the characteristic bell-like sound it makes when gently struck. Only once its key ingredient, a white clay called kaolin, was discovered near Limoges in 1768 could hard-paste porcelain be produced in France. Sèvres immediately adopted this superior material and its director Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847) decided to cease production of soft-paste porcelain and focus exclusively on the new formula in 1801.

Over the next two centuries, the range of materials used at Sèvres expanded even further to encompass many different kinds of ceramics, including grès cérame (stoneware) and faience (a kind of tin-glazed earthenware). Currently, the manufactory uses five different porcelain pastes: pâte tendre (soft paste); pâte dure (hard paste); pâte nouvelle (a “new paste” invented at Sèvres around 1884); pâte Antoine d’Albis (also called PAA, developed at Sèvres in 1965 after the discovery of new kaolin deposits and named for the head of the laboratory); and a new soft-paste porcelain (developed by d’Albis in 1977) that is similar to English bone china. Each new innovation in materials was a direct response to the aesthetic, technological, and economic challenges of its era.

During the first thirty years of its history, the Vincennes-Sèvres factory exclusively produced “soft-paste” porcelain, made from marl (a refined clay) mixed with powdered glass, lead oxide, and chalk to mimic East Asian porcelain. True “hard-paste” porcelain, which was invented and perfected in ancient China, was greatly desired in Europe for its pure whiteness, translucency, imperviousness to water, resistance to temperature, and the characteristic bell-like sound it makes when gently struck. Only once its key ingredient, a white clay called kaolin, was discovered near Limoges in 1768 could hard-paste porcelain be produced in France. Sèvres immediately adopted this superior material and its director Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847) decided to cease production of soft-paste porcelain and focus exclusively on the new formula in 1801.

Over the next two centuries, the range of materials used at Sèvres expanded even further to encompass many different kinds of ceramics, including grès cérame (stoneware) and faience (a kind of tin-glazed earthenware). Currently, the manufactory uses five different porcelain pastes: pâte tendre (soft paste); pâte dure (hard paste); pâte nouvelle (a “new paste” invented at Sèvres around 1884); pâte Antoine d’Albis (also called PAA, developed at Sèvres in 1965 after the discovery of new kaolin deposits and named for the head of the laboratory); and a new soft-paste porcelain (developed by d’Albis in 1977) that is similar to English bone china. Each new innovation in materials was a direct response to the aesthetic, technological, and economic challenges of its era.

Explore:

Explore:

Colors at Sèvres

Although white-matte biscuit porcelain has dominated the production of sculptures, color has always been present at Sèvres. The first commercial success of the early Vincennes workshop featured painted modeled flowers. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Sèvres Manufactory also produced colorful birds, dogs, figures, and groups. New coloring techniques were launched over time, including a cameolike decoration consisting of white-paste subjects in low reliefs on colored backgrounds in the 1780s and the pâte bronze (a bronze-colored paste) in 1798.

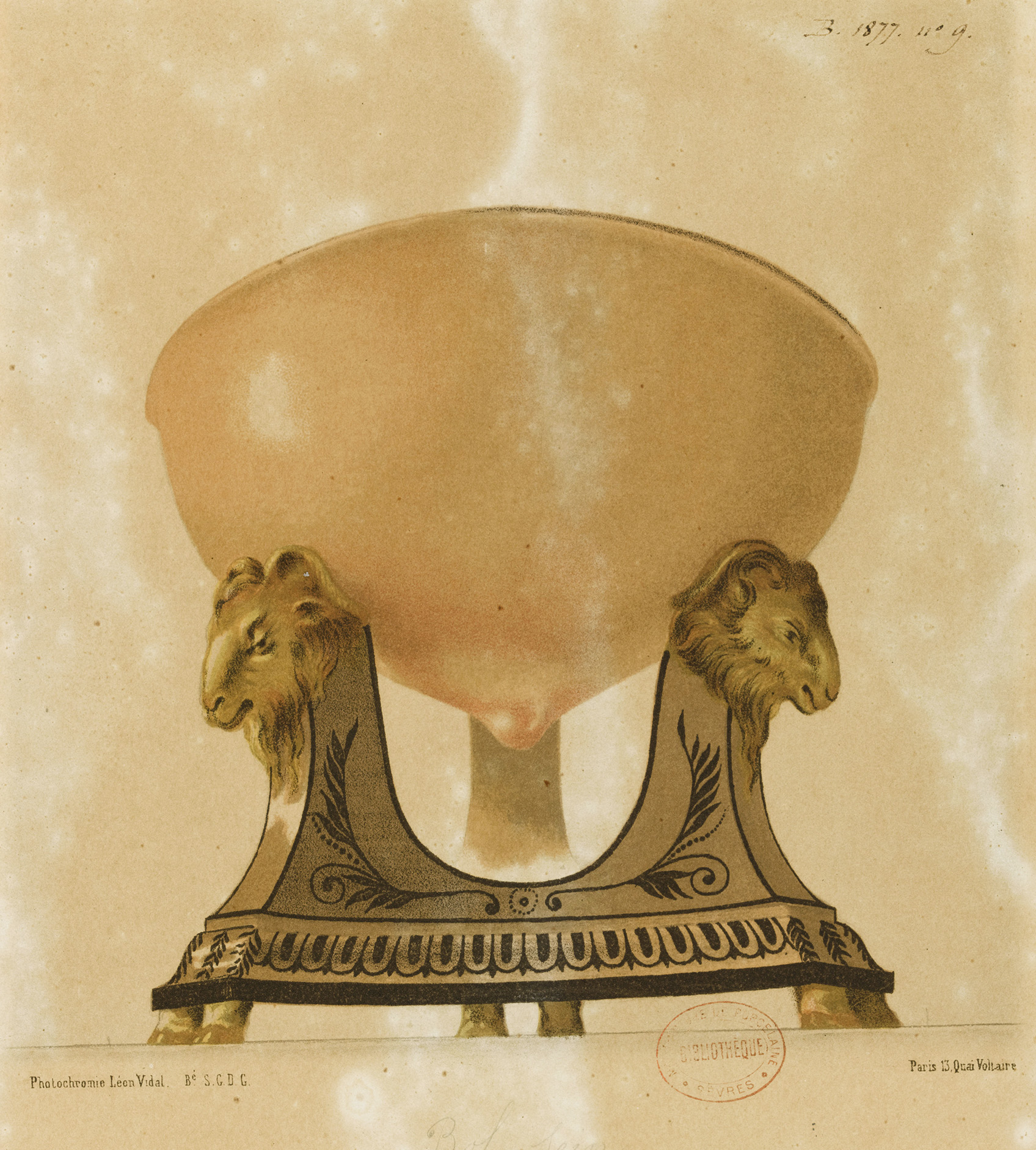

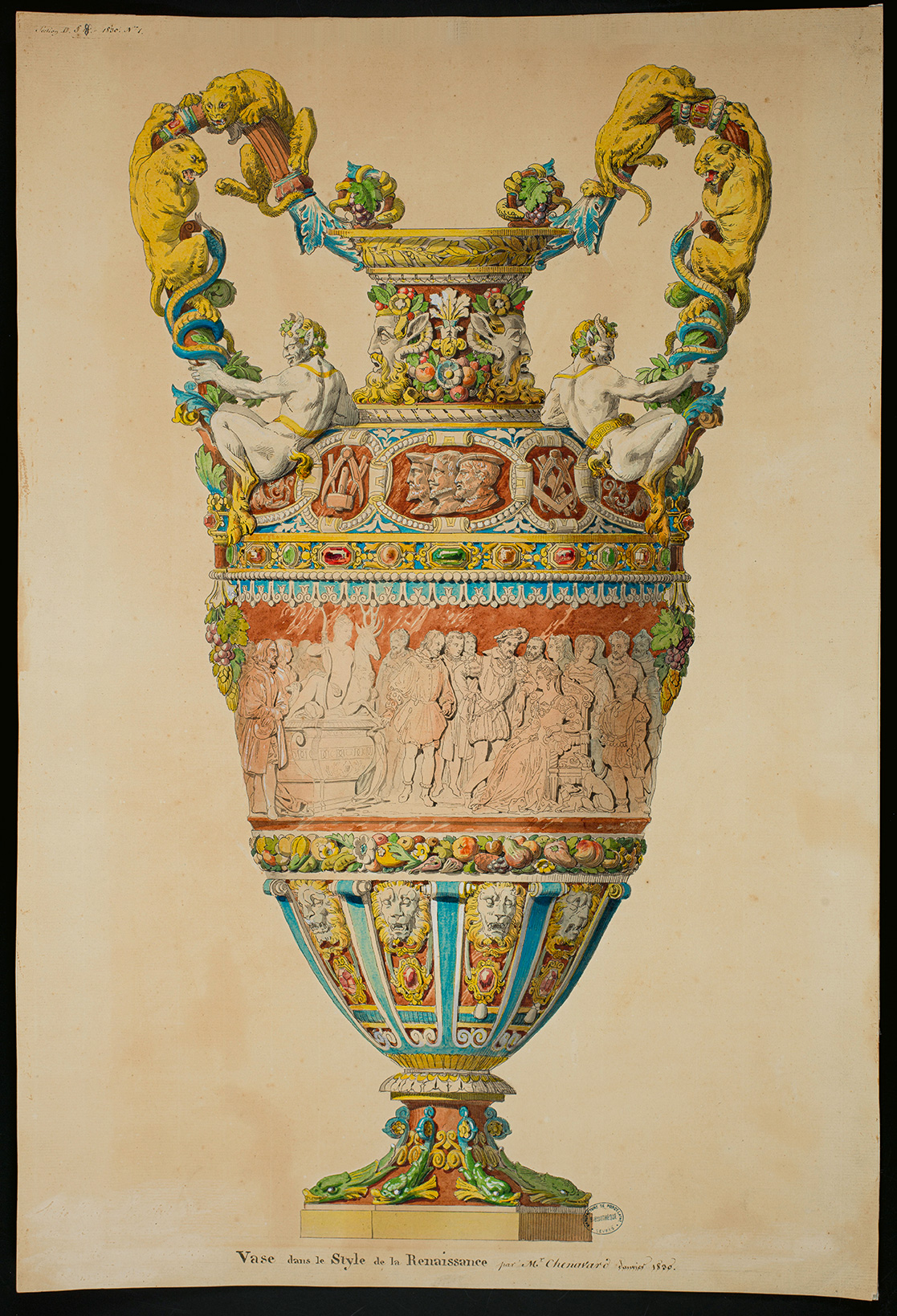

During the nineteenth century, when archeological discoveries unveiled the ancient world’s dramatic polychrome temples and artworks, Claude-Aimé Chenavard’s Renaissance Vase (the preparatory drawing for which is shown here) was a first step toward a full color revival. Around 1850, the manufactory developed the techniques of pâte-sur-pâte (paste-on-paste) and colored pastes, which played with the colorful effects of the glaze’s thickness and offered increasingly varied colored backgrounds.

During the Second Empire (1852–70), many more sculptural pieces used colors on porcelain, and also on glazed pottery and faience (tin-glazed earthenware). Pastes were also entirely tinted, appearing as the base material for biscuit low reliefs. Finally, the pairing of white biscuit and gold, echoing the contrast between glazed and matte elements, has been used from the first introduction of hard-paste porcelain in 1769 up to the present day.

Although white-matte biscuit porcelain has dominated the production of sculptures, color has always been present at Sèvres. The first commercial success of the early Vincennes workshop featured painted modeled flowers. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Sèvres Manufactory also produced colorful birds, dogs, figures, and groups. New coloring techniques were launched over time, including a cameolike decoration consisting of white-paste subjects in low reliefs on colored backgrounds in the 1780s and the pâte bronze (a bronze-colored paste) in 1798.

During the nineteenth century, when archeological discoveries unveiled the ancient world’s dramatic polychrome temples and artworks, Claude-Aimé Chenavard’s Renaissance Vase (the preparatory drawing for which is shown here) was a first step toward a full color revival. Around 1850, the manufactory developed the techniques of pâte-sur-pâte (paste-on-paste) and colored pastes, which played with the colorful effects of the glaze’s thickness and offered increasingly varied colored backgrounds.

During the Second Empire (1852–70), many more sculptural pieces used colors on porcelain, and also on glazed pottery and faience (tin-glazed earthenware). Pastes were also entirely tinted, appearing as the base material for biscuit low reliefs. Finally, the pairing of white biscuit and gold, echoing the contrast between glazed and matte elements, has been used from the first introduction of hard-paste porcelain in 1769 up to the present day.

Watercolor and ink on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2012.1.1659

Watercolor and ink on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2012.1.1659

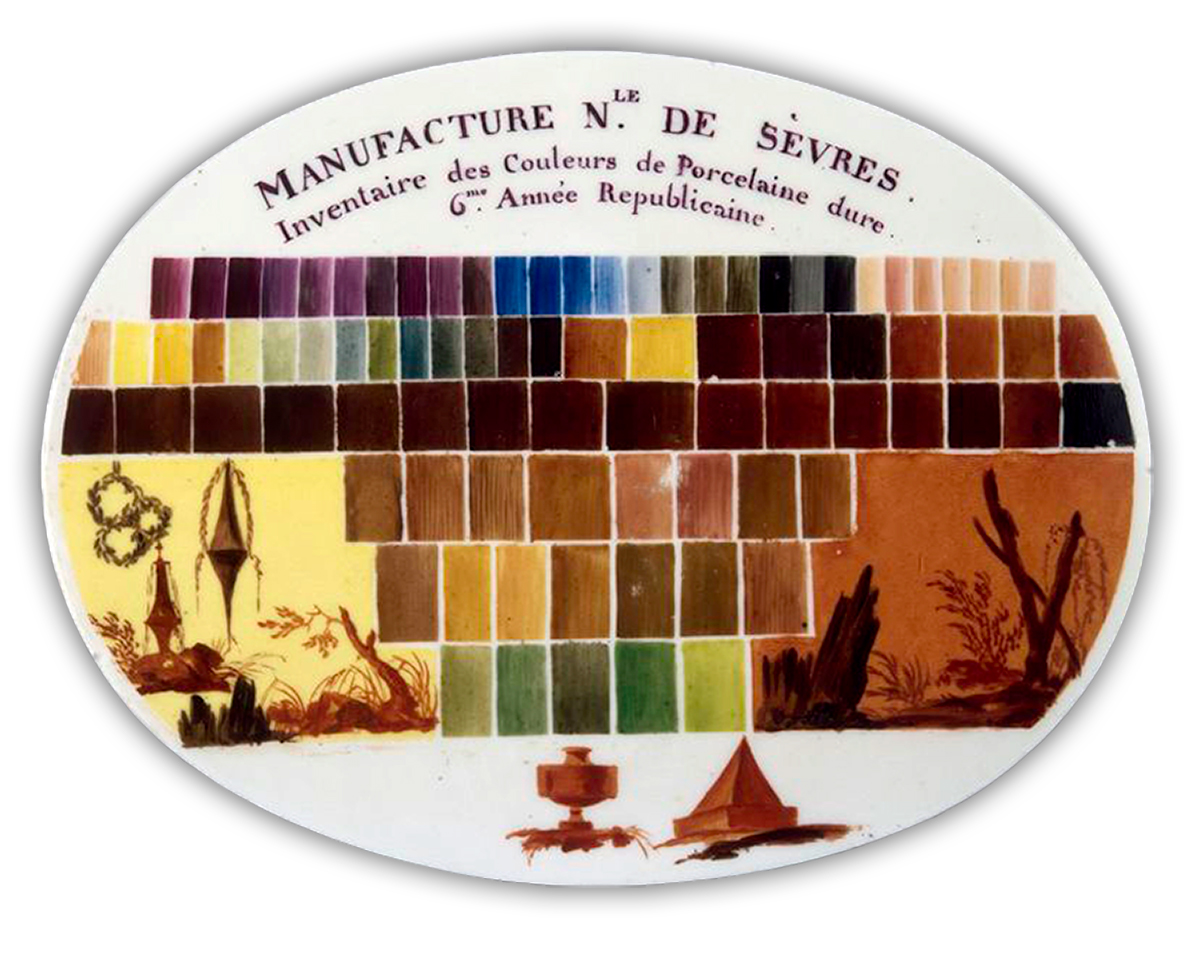

soft porcelain colors, sixth revolutionary year

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

soft porcelain colors, sixth revolutionary year

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

hard porcelain colors, sixth revolutionary year

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / image Grand Palais Rmn

hard porcelain colors, sixth revolutionary year

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / image Grand Palais Rmn

Gold

In the eighteenth century, Sèvres had the exclusive right to use gold, making it a distinctive feature of Sèvres porcelain (as seen in this Peyre cup). The manufactory powders its gold on-site, beginning with a 24-carat ingot from the Banque de France. The gold powder is mixed with lavender oil using a palette knife to give it a liquid consistency.

Gold is applied freehand with a brush. The brushes are chosen according to the technique used: a beveled brush to paint thin gold lines, a broad brush for wider surfaces, and a thinner detail brush. After each application of gold, the piece is fired between 1400 and 1600° F.

Firing makes pure gold matte. It can be polished and made shiny with hard minerals such as agate or hematite, or a fiberglass brush. This step is called burnishing.

In the eighteenth century, Sèvres had the exclusive right to use gold, making it a distinctive feature of Sèvres porcelain (as seen in this Peyre cup). The manufactory powders its gold on-site, beginning with a 24-carat ingot from the Banque de France. The gold powder is mixed with lavender oil using a palette knife to give it a liquid consistency.

Gold is applied freehand with a brush. The brushes are chosen according to the technique used: a beveled brush to paint thin gold lines, a broad brush for wider surfaces, and a thinner detail brush. After each application of gold, the piece is fired between 1400 and 1600° F.

Firing makes pure gold matte. It can be polished and made shiny with hard minerals such as agate or hematite, or a fiberglass brush. This step is called burnishing.

Richard Peduzzi

While at the manufactory in 1995, Richard Peduzzi (b. 1943), a scenographer who has worked for the French opera, created the Reform Vase, a new form consisting of two inverted pyramids fixed to a square stand. Several polychrome versions were produced. This one is enameled with Sèvres’ petit feu colors, which are fired at low temperature, as well as with the historic bleu de Sèvres, a deep blue color from the grand feu palette, fired at higher temperature, which needs to be applied in several layers to obtain the right depth. As it is difficult to shape porcelain into rectilinear forms, the Reform Vase is a significant technical achievement.

While at the manufactory in 1995, Richard Peduzzi (b. 1943), a scenographer who has worked for the French opera, created the Reform Vase, a new form consisting of two inverted pyramids fixed to a square stand. Several polychrome versions were produced. This one is enameled with Sèvres’ petit feu colors, which are fired at low temperature, as well as with the historic bleu de Sèvres, a deep blue color from the grand feu palette, fired at higher temperature, which needs to be applied in several layers to obtain the right depth. As it is difficult to shape porcelain into rectilinear forms, the Reform Vase is a significant technical achievement.

Glazed and colored soft-paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 27846

© Richard Peduzzi

Hover over image to view the reverse side of this object.

Glazed and colored soft-paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 27846

© RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

© Richard Peduzzi

Blue

The Sèvres Manufactory has long been known for its distinct shades of blue. The blue color is obtained by mixing cobalt oxide powder with turpentine. This mix is applied with a wide cod tail brush and evened out with a badger brush.

The color is matte before it is fired. The 2500°F firing reveals the subtlety of colors. Sèvres Blue comes in various shades, according to the number of layers or the technique used.

The Sèvres Manufactory has long been known for its distinct shades of blue. The blue color is obtained by mixing cobalt oxide powder with turpentine. This mix is applied with a wide cod tail brush and evened out with a badger brush.

The color is matte before it is fired. The 2500°F firing reveals the subtlety of colors. Sèvres Blue comes in various shades, according to the number of layers or the technique used.

The Sèvres Manufactory has long been known for its distinct shades of blue. The blue color is obtained by mixing cobalt oxide powder with turpentine. This mix is applied with a wide cod tail brush and evened out with a badger brush.

The color is matte before it is fired. The 2500°F firing reveals the subtlety of colors. Sèvres Blue comes in various shades, according to the number of layers or the technique used.