Surtout

de

Table

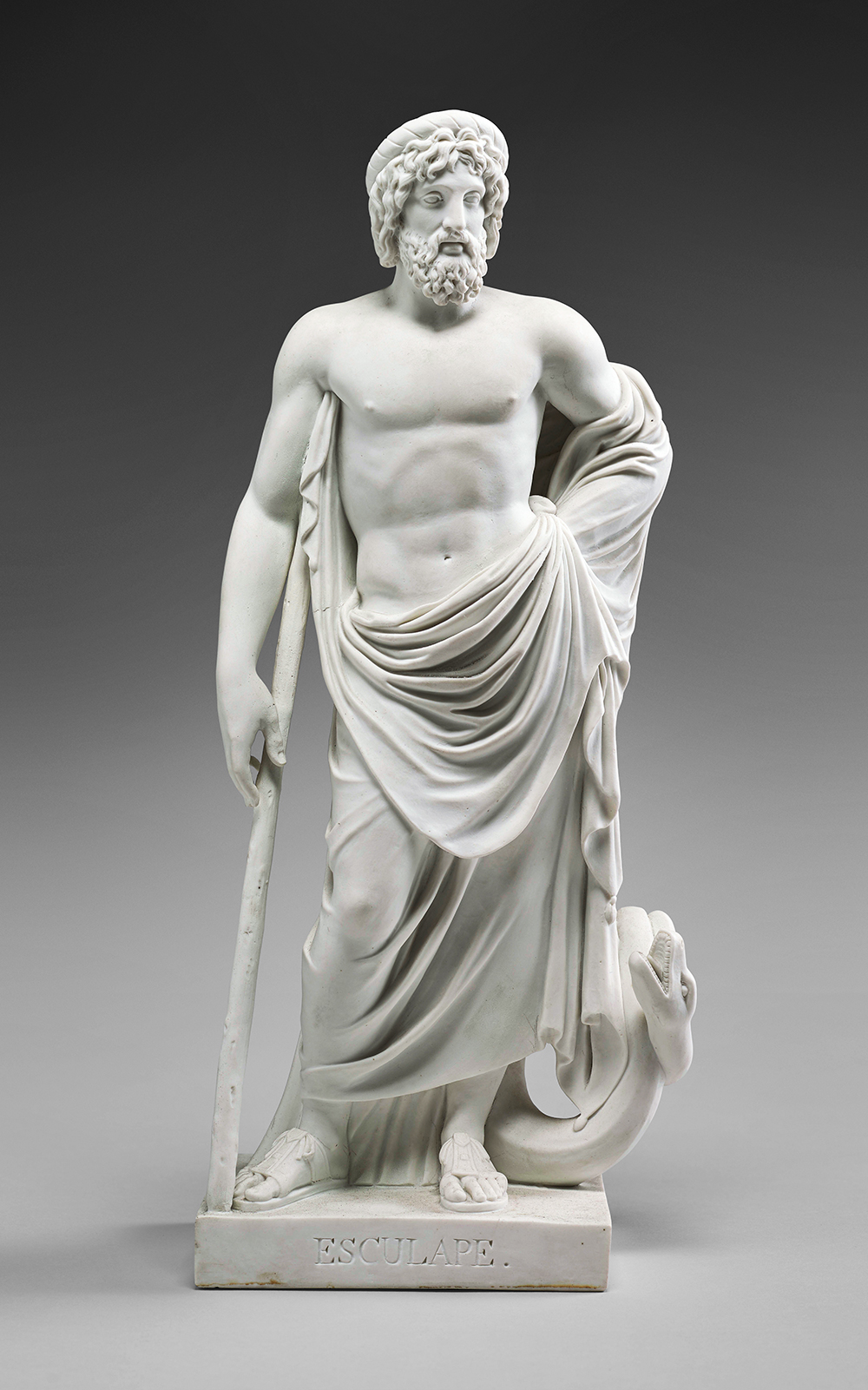

In the eighteenth century, the surtouts de table (table centerpieces) made at the Sèvres Manufactory consisted of numerous elements in biscuit porcelain, including baskets, figurines and groups, flowers, miniaturized architectural elements, and vases. Placed on mirrored trays with colored sugar decorations imitating geometric garden designs à la française, lit by candelabras, and sometimes accompanied by natural flowers, they decorated the center of a table for the dessert course of a dîner à la française. When not in use as table decorations, the figurines and groups were often placed elsewhere in the house, such as on top of mantelpieces, tables, or chests of drawers.

During the reign of Napoleon I, the centerpieces became more elaborate with all elements thematically and aesthetically related to the decoration of the plates, platters, tureens, and other pieces of the table service. The display of these elements was strictly planned on the table and recorded with preparatory drawings, although these recommendations were not always followed.

Centerpieces continued to be produced at Sèvres during the nineteenth century, often commissioned by the sovereign of the time. The manufactory also produced impressive pieces for international exhibitions. Once created to grace the tables of kings and emperors, centerpieces are now considered sculptures in their own right.

Surtout de Table

In the eighteenth century, the surtouts de table (table centerpieces) made at the Sèvres Manufactory consisted of numerous elements in biscuit porcelain, including baskets, figurines and groups, flowers, miniaturized architectural elements, and vases. Placed on mirrored trays with colored sugar decorations imitating geometric garden designs à la française, lit by candelabras, and sometimes accompanied by natural flowers, they decorated the center of a table for the dessert course of a dîner à la française. When not in use as table decorations, the figurines and groups were often placed elsewhere in the house, such as on top of mantelpieces, tables, or chests of drawers.

During the reign of Napoleon I, the centerpieces became more elaborate with all elements thematically and aesthetically related to the decoration of the plates, platters, tureens, and other pieces of the table service. The display of these elements was strictly planned on the table and recorded with preparatory drawings, although these recommendations were not always followed.

Centerpieces continued to be produced at Sèvres during the nineteenth century, often commissioned by the sovereign of the time. The manufactory also produced impressive pieces for international exhibitions. Once created to grace the tables of kings and emperors, centerpieces are now considered sculptures in their own right.

In the eighteenth century, the surtouts de table (table centerpieces) made at the Sèvres Manufactory consisted of numerous elements in biscuit porcelain, including baskets, figurines and groups, flowers, miniaturized architectural elements, and vases. Placed on mirrored trays with colored sugar decorations imitating geometric garden designs à la française, lit by candelabras, and sometimes accompanied by natural flowers, they decorated the center of a table for the dessert course of a dîner à la française. When not in use as table decorations, the figurines and groups were often placed elsewhere in the house, such as on top of mantelpieces, tables, or chests of drawers.

During the reign of Napoleon I, the centerpieces became more elaborate with all elements thematically and aesthetically related to the decoration of the plates, platters, tureens, and other pieces of the table service. The display of these elements was strictly planned on the table and recorded with preparatory drawings, although these recommendations were not always followed.

Centerpieces continued to be produced at Sèvres during the nineteenth century, often commissioned by the sovereign of the time. The manufactory also produced impressive pieces for international exhibitions. Once created to grace the tables of kings and emperors, centerpieces are now considered sculptures in their own right.

Le Parnasse de Russie (The Russian Parnassus)

This astonishing biscuit sculpture is the central piece of the 800-piece table service commissioned in 1777 by Catherine II, empress of Russia (r. 1762–96), and delivered two years later in Saint Petersburg. Louis- Simon Boizot modeled its design in accordance with strict instructions received from Russia: to create a centerpiece depicting allegories of the arts and sciences that pay homage to Catherine, whose bust was to crown a central column. The Russian sovereign disliked her bust however, and had it replaced by one of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and justice and patron of the arts. Boizot’s decision to group all the allegories on the same rock was likely inspired by the Parnasse français (French Parnassus), a large bronze sculpture made in 1718 by Louis Garnier (ca. 1639–1728) that features Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715) as Apollo in the central position.

This astonishing biscuit sculpture is the central piece of the 800-piece table service commissioned in 1777 by Catherine II, empress of Russia (r. 1762–96), and delivered two years later in Saint Petersburg. Louis- Simon Boizot modeled its design in accordance with strict instructions received from Russia: to create a centerpiece depicting allegories of the arts and sciences that pay homage to Catherine, whose bust was to crown a central column. The Russian sovereign disliked her bust however, and had it replaced by one of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and justice and patron of the arts. Boizot’s decision to group all the allegories on the same rock was likely inspired by the Parnasse français (French Parnassus), a large bronze sculpture made in 1718 by Louis Garnier (ca. 1639–1728) that features Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715) as Apollo in the central position.

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 23240

Le Jeu de l’écharpe (The Scarf Dance)

This table centerpiece was the undisputed masterpiece from the Sèvres Manufactory exhibited at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It features fifteen different dancing female figures, their sinuous, high-waisted dresses, large sleeves, and billowing scarves emphasizing their movements. Sculptor Agathon Léonard (1841–1923) was inspired by the “serpentine dance” created by the American dancer Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) in 1891. Fuller’s innovative choreography performed with silk costumes illuminated by multicolored lighting of her own design became a true embodiment of the Art Nouveau movement. In October 1901, an example of this centerpiece was offered as a diplomatic gift to the tsar and the empress consort of Russia (r. 1894–1917), who gave it to the Hermitage—the first example of Art Nouveau to enter the collection of the Russian museum.

This table centerpiece was the undisputed masterpiece from the Sèvres Manufactory exhibited at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It features fifteen different dancing female figures, their sinuous, high-waisted dresses, large sleeves, and billowing scarves emphasizing their movements. Sculptor Agathon Léonard (1841–1923) was inspired by the “serpentine dance” created by the American dancer Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) in 1891. Fuller’s innovative choreography performed with silk costumes illuminated by multicolored lighting of her own design became a true embodiment of the Art Nouveau movement. In October 1901, an example of this centerpiece was offered as a diplomatic gift to the tsar and the empress consort of Russia (r. 1894–1917), who gave it to the Hermitage—the first example of Art Nouveau to enter the collection of the Russian museum.

Pâte nouvelle porcelain biscuit and stands with gilding

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 17270 (no. 1), 17266 (no. 3), 16215 (no. 6), 17262 bis R (no. 7), 17266 bis (no. 11), 16216 (no. 12), 16224 (no. 13), 24761 (central stand), 24760.2, .3 (side stands)

Danseuse no. 11 (Dancer no. 11)

Danseuse no. 3 (Dancer no. 3)

Danseuse no. 7 (Dancer no. 7)

Danseuse no. 12 (Dancer no. 12)

Danseuse no. 6 (Dancer no. 6)

Danseuse no. 1 (Dancer no. 1)

Danseuse no. 13 (Dancer no. 13)

Click figures to enlarge.

Pâte nouvelle porcelain biscuit and stands with gilding

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 17270 (no. 1), 17266 (no. 3), 16215 (no. 6), 17262 bis R (no. 7), 17266 bis (no. 11), 16216 (no. 12), 16224 (no. 13), 24761 (central stand), 24760.2, .3 (side stands)

Surtouts as Contemporary Sculpture

The art of the surtout de table (table centerpiece), whose origin at Sèvres goes back to the eighteenth century, has been spectacularly developed by sculptors during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These pieces adapt the aesthetic principles of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century centerpiece for modern tastes, replacing elaborately sculpted decorative forms and figuration with simple lines, solid blocks of color, and abstract or Pop art–inspired elements. Some centerpieces pay tribute to contemporary luminaries, others refer to historical individuals, artworks, and events.

Many artists choose to produce their centerpieces in Sèvres’ most storied material—biscuit. For some, the use of this matte-white material borders on abstraction; others explore its textural variations or play with its subtleties of light and shadow. Biscuit’s long association with gold and other metals also features prominently, but a spectrum of colors has been added to this traditional palette. Some glazes and enamels featured on these artworks, such as bleu de Sèvres, have long been manufactured at Sèvres. The manufactory’s chemists continue to develop new color formulations, occasionally collaborating with artists to meet their exacting visions.

The art of the surtout de table (table centerpiece), whose origin at Sèvres goes back to the eighteenth century, has been spectacularly developed by sculptors during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These pieces adapt the aesthetic principles of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century centerpiece for modern tastes, replacing elaborately sculpted decorative forms and figuration with simple lines, solid blocks of color, and abstract or Pop art–inspired elements. Some centerpieces pay tribute to contemporary luminaries, others refer to historical individuals, artworks, and events.

Many artists choose to produce their centerpieces in Sèvres’ most storied material—biscuit. For some, the use of this matte-white material borders on abstraction; others explore its textural variations or play with its subtleties of light and shadow. Biscuit’s long association with gold and other metals also features prominently, but a spectrum of colors has been added to this traditional palette. Some glazes and enamels featured on these artworks, such as bleu de Sèvres, have long been manufactured at Sèvres. The manufactory’s chemists continue to develop new color formulations, occasionally collaborating with artists to meet their exacting visions.

The art of the surtout de table (table centerpiece), whose origin at Sèvres goes back to the eighteenth century, has been spectacularly developed by sculptors during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These pieces adapt the aesthetic principles of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century centerpiece for modern tastes, replacing elaborately sculpted decorative forms and figuration with simple lines, solid blocks of color, and abstract or Pop art–inspired elements. Some centerpieces pay tribute to contemporary luminaries, others refer to historical individuals, artworks, and events.

Many artists choose to produce their centerpieces in Sèvres’ most storied material—biscuit. For some, the use of this matte-white material borders on abstraction; others explore its textural variations or play with its subtleties of light and shadow. Biscuit’s long association with gold and other metals also features prominently, but a spectrum of colors has been added to this traditional palette. Some glazes and enamels featured on these artworks, such as bleu de Sèvres, have long been manufactured at Sèvres. The manufactory’s chemists continue to develop new color formulations, occasionally collaborating with artists to meet their exacting visions.

Andrea Branzi

Sculptor Andrea Branzi (b. 1938) invokes the storied tradition of royal patronage at Sèvres by giving this piece the name of a fictitious French king, Louis XXI. Similarly, his choice of material—soft-paste biscuit porcelain—makes clear the continuous transmission of artisanal knowledge at the manufactory. This set comprises eight coupes, chalices, and forms he describes as “corollas,” complemented by three undulating candlesticks on delicate bases. While independent, the different pieces are grouped to suggest, according to Branzi’s vision, “a family of mushrooms, sea anemones, or sexual organs.”

Sculptor Andrea Branzi (b. 1938) invokes the storied tradition of royal patronage at Sèvres by giving this piece the name of a fictitious French king, Louis XXI. Similarly, his choice of material—soft-paste biscuit porcelain—makes clear the continuous transmission of artisanal knowledge at the manufactory. This set comprises eight coupes, chalices, and forms he describes as “corollas,” complemented by three undulating candlesticks on delicate bases. While independent, the different pieces are grouped to suggest, according to Branzi’s vision, “a family of mushrooms, sea anemones, or sexual organs.”

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2020.D.83

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Jonca. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2020.D.83

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Jonca. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

PAA porcelain biscuit, partly glazed and decorated

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.3310 (1–25)

Photographer: Gérard Jonca. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

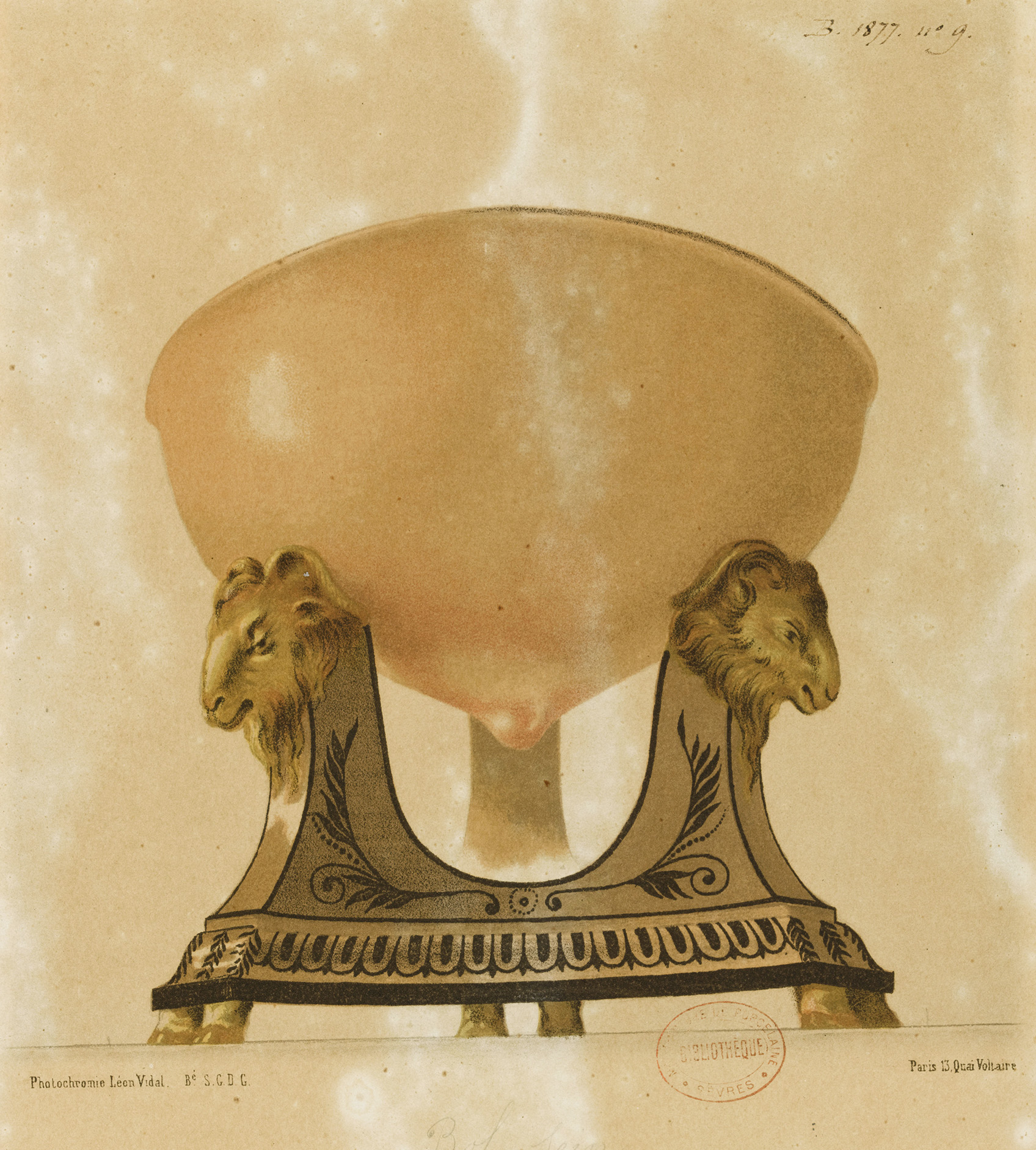

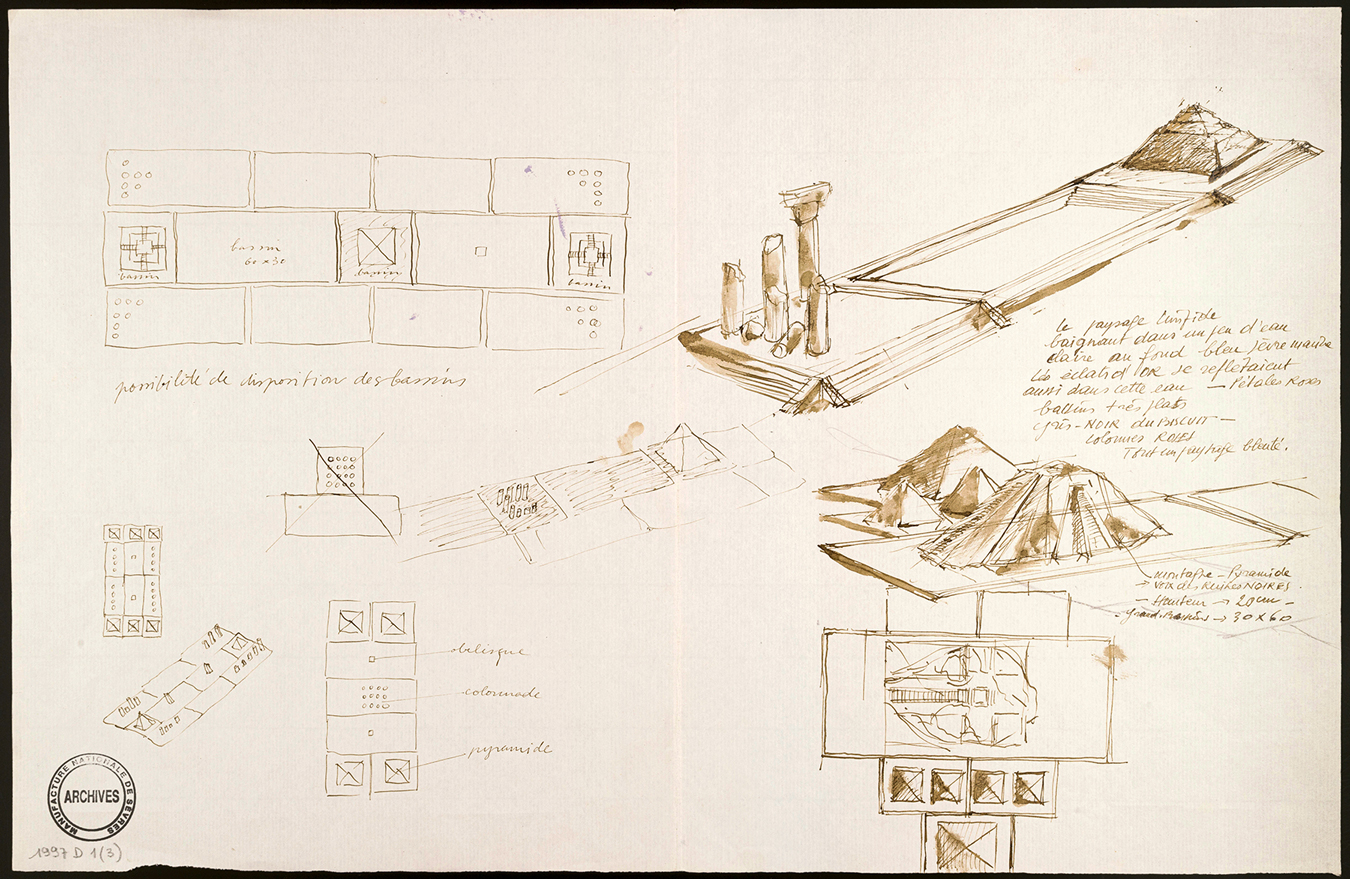

Pen and ink on paper

Inscriptions [above, left, sepia ink]: possibilité de disposition des bassins; [above, right, sepia ink]: Le paysage limpide/baignant dans un peu d’eau/claire au fond bleu Sèvres [sic] marine/Les éclats d’OR se reflétaient/aussi dans cette eau – Pétales roses/bassins très plats/gris-NOIR du BISCUIT -/ colonnes ROSES/ Tout un paysage bleuté; [half height, right, sepia ink]: montagne/Pyramide/voix des Ruines NOIRES: hauteur 20 cm/Grands bassins 30 × 60; [bottom left near the drawing]: Obélisque/Colonnade/Pyramide

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 1997.D.1(3)

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Manzara. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Anne and Patrick Poirier

Anne (b. 1941) and Patrick Poirier (b. 1942) are a French art duo whose practice encompasses sculpture, architecture, and archaeology. Their artworks often explore the complicated legacy of classical art and architecture in the modern world. For this centerpiece, entitled Ruins of Egypt, they collaborated with the Sèvres Manufactory to create a miniature version of the Egyptian Temple of Philae, reveling in its grandeur and decay. This work refers to the Egyptian Centerpiece made for Napoleon I in 1808, which was based on illustrations from Voyage dans la Basse et dans la Haute Égypte (Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt), by Dominique-Vivant Denon, the artist, diplomat, and archaeologist who accompanied Bonaparte on his Egyptian Campaign. The Poiriers chose materials emblematic of the manufactory’s traditions: biscuit pâte Antoine d’Albis embellished with gold and bleu de Sèvres.

Anne (b. 1941) and Patrick Poirier (b. 1942) are a French art duo whose practice encompasses sculpture, architecture, and archaeology. Their artworks often explore the complicated legacy of classical art and architecture in the modern world. For this centerpiece, entitled Ruins of Egypt, they collaborated with the Sèvres Manufactory to create a miniature version of the Egyptian Temple of Philae, reveling in its grandeur and decay. This work refers to the Egyptian Centerpiece made for Napoleon I in 1808, which was based on illustrations from Voyage dans la Basse et dans la Haute Égypte (Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt), by Dominique-Vivant Denon, the artist, diplomat, and archaeologist who accompanied Bonaparte on his Egyptian Campaign. The Poiriers chose materials emblematic of the manufactory’s traditions: biscuit pâte Antoine d’Albis embellished with gold and bleu de Sèvres.

PAA porcelain biscuit, partly glazed and decorated

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.3310 (1–25)

Photographer: Gérard Jonca. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Pen and ink on paper

Inscriptions [above, left, sepia ink]: possibilité de disposition des bassins; [above, right, sepia ink]: Le paysage limpide/baignant dans un peu d’eau/claire au fond bleu Sèvres [sic] marine/Les éclats d’OR se reflétaient/aussi dans cette eau – Pétales roses/bassins très plats/gris-NOIR du BISCUIT -/ colonnes ROSES/ Tout un paysage bleuté; [half height, right, sepia ink]: montagne/Pyramide/voix des Ruines NOIRES: hauteur 20 cm/Grands bassins 30 × 60; [bottom left near the drawing]: Obélisque/Colonnade/Pyramide

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 1997.D.1(3)

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Manzara. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Ettore Sottsass

Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007), the Italian designer and founder of the Memphis movement, designed this contemporary centerpiece for Sèvres during his first residency at the manufactory between 1994 and 1996. He used a range of traditional shaping techniques to create the set’s components: a circular central base into which seven columns are inserted, surrounded by eleven smaller mobile elements. Realized in white biscuit soft- paste porcelain, Surtout Sottsass is sumptuously adorned in burnished gold. The geometric play of simple shapes—spheres, cups, and cylinders— stacked to evoke more complex forms, echoes that of Vase Diane, created during the same residency.

Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007), the Italian designer and founder of the Memphis movement, designed this contemporary centerpiece for Sèvres during his first residency at the manufactory between 1994 and 1996. He used a range of traditional shaping techniques to create the set’s components: a circular central base into which seven columns are inserted, surrounded by eleven smaller mobile elements. Realized in white biscuit soft- paste porcelain, Surtout Sottsass is sumptuously adorned in burnished gold. The geometric play of simple shapes—spheres, cups, and cylinders— stacked to evoke more complex forms, echoes that of Vase Diane, created during the same residency.

Glazed, partly gilt, and biscuit soft-paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.3311

Glazed, partly gilt, and biscuit soft-paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.3311