Sèvres

&

the French State

From the moment that Louis XV (r. 1715–74) assumed management of Sèvres in 1759, the manufactory has been the property of the French state. Long envied by other manufactories, this special relationship has had many benefits. Never expected to make a profit, the manufactory could devote itself to enhancing the global prestige of French decorative arts, a purpose also furthered by the tradition of gifting Sèvres porcelain to foreign dignitaries and heads of state. Periods of financial stability have enabled investment in expensive technical research, the fruits of which were made available to all French ceramists. State patronage attracted leading artists who were keen to work for the royal, imperial, or national manufactory. Perhaps most significantly, the manufactory has avoided industrialization, allowing it to preserve and transmit its unique artisanal knowledge. Public ownership has also made it possible to preserve most of the Sèvres archives—a rarity among ceramic factories and a boon for scholarship.

There are, however, significant drawbacks to public ownership. France’s turbulent history has exposed Sèvres to a succession of financial and political crises, including revolutions, wars, and civil unrest. During the French Revolution, Sèvres endured severe budget cuts and its traditional clientele disappeared. Despite continuing criticism that it was an institution producing luxuries for the elite, the manufactory has survived demands it be closed. As the state changed, Sèvres remained a constant, accommodating itself to the tastes—and occasionally the political demands—of new regimes. Finally, except for a short period of financial autonomy from 1926 to 1941, the manufactory’s revenues and budgets have been tied to those of the state, an issue that complicates its day-to-day organization.

Sèvres & The French State

From the moment that Louis XV (r. 1715–74) assumed management of Sèvres in 1759, the manufactory has been the property of the French state. Long envied by other manufactories, this special relationship has had many benefits. Never expected to make a profit, the manufactory could devote itself to enhancing the global prestige of French decorative arts, a purpose also furthered by the tradition of gifting Sèvres porcelain to foreign dignitaries and heads of state. Periods of financial stability have enabled investment in expensive technical research, the fruits of which were made available to all French ceramists. State patronage attracted leading artists who were keen to work for the royal, imperial, or national manufactory. Perhaps most significantly, the manufactory has avoided industrialization, allowing it to preserve and transmit its unique artisanal knowledge. Public ownership has also made it possible to preserve most of the Sèvres archives—a rarity among ceramic factories and a boon for scholarship.

There are, however, significant drawbacks to public ownership. France’s turbulent history has exposed Sèvres to a succession of financial and political crises, including revolutions, wars, and civil unrest. During the French Revolution, Sèvres endured severe budget cuts and its traditional clientele disappeared. Despite continuing criticism that it was an institution producing luxuries for the elite, the manufactory has survived demands it be closed. As the state changed, Sèvres remained a constant, accommodating itself to the tastes—and occasionally the political demands—of new regimes. Finally, except for a short period of financial autonomy from 1926 to 1941, the manufactory’s revenues and budgets have been tied to those of the state, an issue that complicates its day-to-day organization.

From the moment that Louis XV (r. 1715–74) assumed management of Sèvres in 1759, the manufactory has been the property of the French state. Long envied by other manufactories, this special relationship has had many benefits. Never expected to make a profit, the manufactory could devote itself to enhancing the global prestige of French decorative arts, a purpose also furthered by the tradition of gifting Sèvres porcelain to foreign dignitaries and heads of state. Periods of financial stability have enabled investment in expensive technical research, the fruits of which were made available to all French ceramists. State patronage attracted leading artists who were keen to work for the royal, imperial, or national manufactory. Perhaps most significantly, the manufactory has avoided industrialization, allowing it to preserve and transmit its unique artisanal knowledge. Public ownership has also made it possible to preserve most of the Sèvres archives—a rarity among ceramic factories and a boon for scholarship.

There are, however, significant drawbacks to public ownership. France’s turbulent history has exposed Sèvres to a succession of financial and political crises, including revolutions, wars, and civil unrest. During the French Revolution, Sèvres endured severe budget cuts and its traditional clientele disappeared. Despite continuing criticism that it was an institution producing luxuries for the elite, the manufactory has survived demands it be closed. As the state changed, Sèvres remained a constant, accommodating itself to the tastes—and occasionally the political demands—of new regimes. Finally, except for a short period of financial autonomy from 1926 to 1941, the manufactory’s revenues and budgets have been tied to those of the state, an issue that complicates its day-to-day organization.

L’Amitié (Friendship)

In 1755 Madame de Pompadour, a staunch supporter of the Vincennes workshop, ordered this figurine of herself as Philotes, the goddess of friendship, from the sculptor Etienne-Maurice Falconet. She wished to demonstrate that, although she was no longer the mistress of King Louis XV, she was still an influential friend. She made the bold choice to have it produced in the newly adopted biscuit medium, helping to promote this innovative material.

In 1755 Madame de Pompadour, a staunch supporter of the Vincennes workshop, ordered this figurine of herself as Philotes, the goddess of friendship, from the sculptor Etienne-Maurice Falconet. She wished to demonstrate that, although she was no longer the mistress of King Louis XV, she was still an influential friend. She made the bold choice to have it produced in the newly adopted biscuit medium, helping to promote this innovative material.

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 16057

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 16057

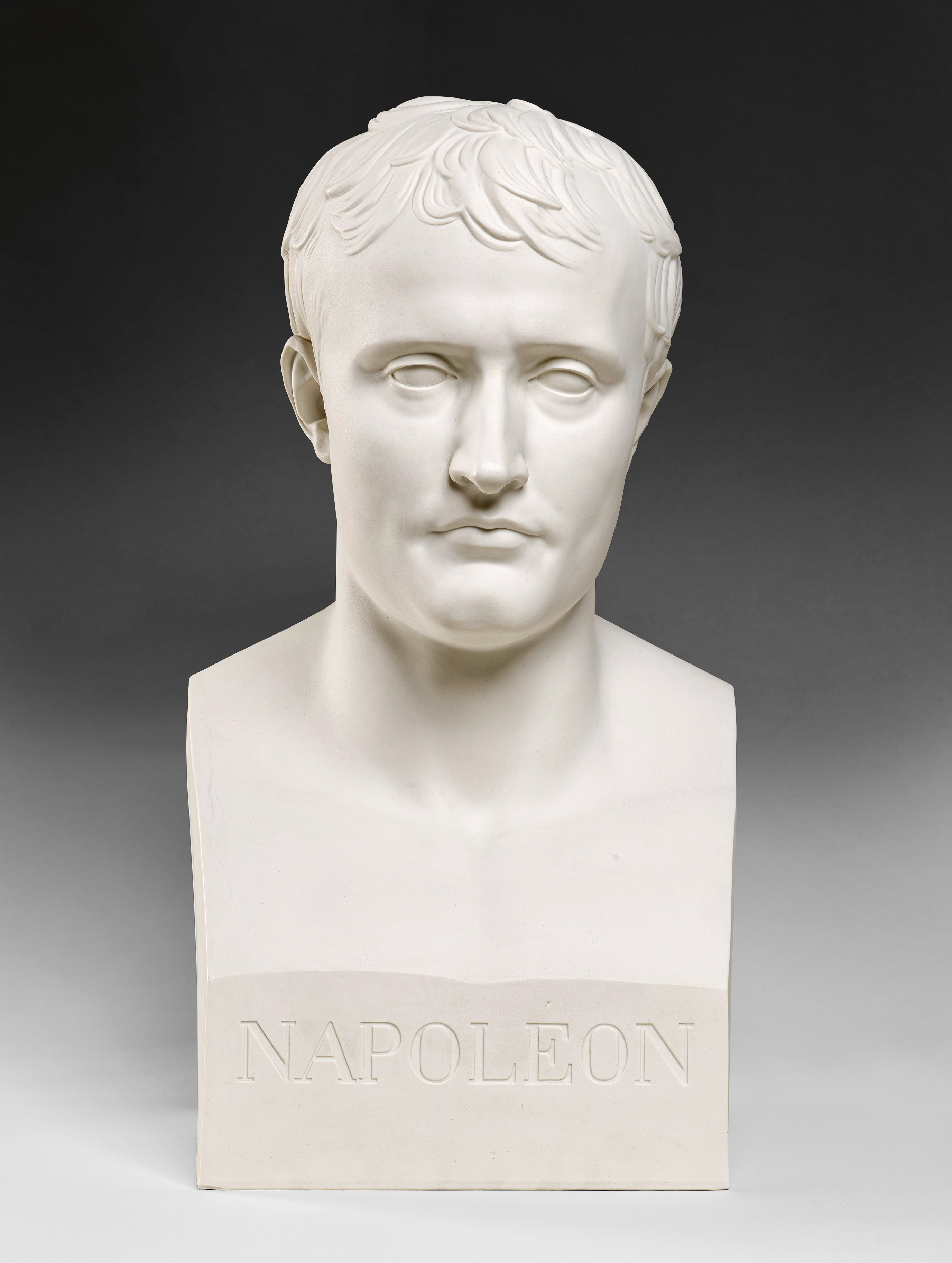

Napoléon Ier

In 1798 the first bust and medallion of General Napoleon Bonaparte were made, both by Boizot. Despite doubts, these sold so well that they dominated the manufactory’s production. In 1804, when the sitter was proclaimed Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804–14, 1815), Sèvres signed an agreement with the sculptor Antoine Denis Chaudet (1763–1810) for the exclusive right to produce porcelain versions, in two sizes, of this official bust. Starting in 1808, the bust could be enhanced with a bronze crown of laurels. It was further revised in 1811, when it was given shoulders, draping, and a shoulder belt, as well as a crown in either bronze or porcelain.

In 1798 the first bust and medallion of General Napoleon Bonaparte were made, both by Boizot. Despite doubts, these sold so well that they dominated the manufactory’s production. In 1804, when the sitter was proclaimed Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804–14, 1815), Sèvres signed an agreement with the sculptor Antoine Denis Chaudet (1763–1810) for the exclusive right to produce porcelain versions, in two sizes, of this official bust. Starting in 1808, the bust could be enhanced with a bronze crown of laurels. It was further revised in 1811, when it was given shoulders, draping, and a shoulder belt, as well as a crown in either bronze or porcelain.

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2016.D.2304

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Sèvres, MNS 2016.D.2304

La Famille d’Orléans (Members of the Orléans Family)

The July Revolution of 1830 led to the overthrow of the Bourbon king Charles X, whose family had been reinstated after the fall of the Empire of Napoleon I. Charles X was replaced by his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans. Crowned king in 1830, Louis-Philippe established a parliamentary monarchy that lasted eighteen years, until the Revolution of 1848.

In 1835 the medalist Jean Jacques Barre père (1793–1855) created a set of profiles of the Orléans family, which were then used at Sèvres to produce a series of medallions in white biscuit on a blue background, including those shown here. Widely distributed, these medallions were effective propaganda, contributing to the fame of the Orléans family during the nineteenth century.

The July Revolution of 1830 led to the overthrow of the Bourbon king Charles X, whose family had been reinstated after the fall of the Empire of Napoleon I. Charles X was replaced by his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans. Crowned king in 1830, Louis-Philippe established a parliamentary monarchy that lasted eighteen years, until the Revolution of 1848.

In 1835 the medalist Jean Jacques Barre père (1793–1855) created a set of profiles of the Orléans family, which were then used at Sèvres to produce a series of medallions in white biscuit on a blue background, including those shown here. Widely distributed, these medallions were effective propaganda, contributing to the fame of the Orléans family during the nineteenth century.

Blue and white hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.569, 572–73, 575, 577, 580, 582–85, 588–90, 593–94, 601

Click medallions to enlarge.

Madame Adélaïde d’Orléans

Louis Philippe, roi des Français

Victoire, duchesse de Nemours

François, prince de Joinville

Léopold 1er, roi des Belges

Clémentine d’Orléans

Marie Amélie, reine des Français

Louis Charles, duc de Nemours

Ferdinand Philippe, duc d’Orléans

Henri, duc d’Aumale

Antoine, duc de Montpensier

Hélène Louise, duchesse d’Orléans

Ferdinand Philippe, duc d’Orléans

Louise Marie d’Orléans, reine des Belge

Marie d’Orléans, reine des Belge

François, prince de Joinville

Click medallions to enlarge.

Blue and white hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.569, 572–73, 575, 577, 580, 582–85, 588–90, 593–94, 601