18th Century

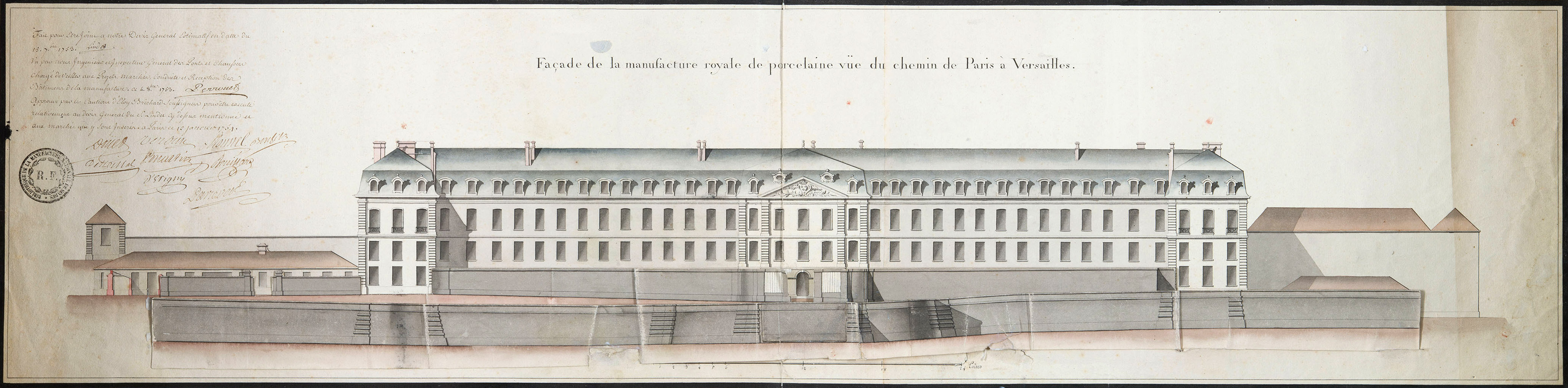

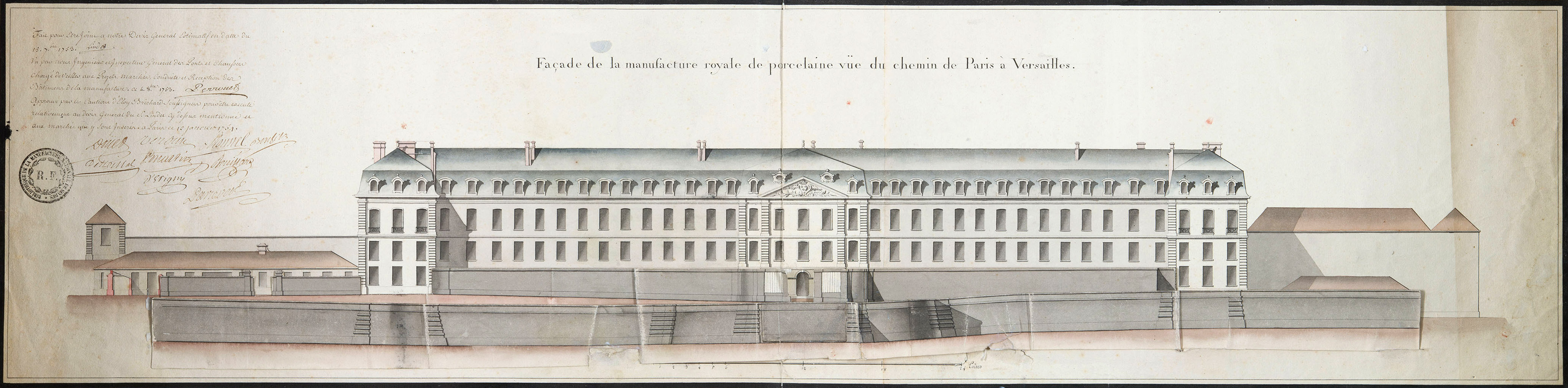

In 1740 a small group of artisans, who worked at the porcelain factory of the prince de Condé at Chantilly, along with a carpenter, Claude-Humbert Gérin (ca. 1705–1750), who had discovered the secret to making very white “soft-paste” porcelain, set up a workshop in some disused buildings at the Château de Vincennes. They obtained a loan from the royal treasury and additional funding from the workshop’s original financier, the king’s Intendant des Finances and commissioner for the French East India Company, Jean-Henri-Louis Orry de Fulvy (1703–1751). In 1745 Fulvy obtained a royal privilege, giving the manufactory the exclusive right to produce porcelain “in the Saxon manner, that is, painted and gilded with human figures.” The fledgling company hoped to compete with porcelain imported from East Asia as well as that produced at the Meissen factory in Saxony, whose success was a drain on the French economy.

In 1756 the workshop moved to the town of Sèvres, halfway between Paris and Versailles. Nearby was the Château de Bellevue, built for Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), Louis XV’s mistress and a porcelain aficionado who became a powerful advocate for the manufactory. Three years later, the king became the company’s principal stockholder and took Sèvres under direct management and under the aegis of the crown. Through his patronage, Sèvres became the most important producer of soft-paste porcelain in Europe.

18th Century

In 1740 a small group of artisans, who worked at the porcelain factory of the prince de Condé at Chantilly, along with a carpenter, Claude-Humbert Gérin (ca. 1705–1750), who had discovered the secret to making very white “soft-paste” porcelain, set up a workshop in some disused buildings at the Château de Vincennes. They obtained a loan from the royal treasury and additional funding from the workshop’s original financier, the king’s Intendant des Finances and commissioner for the French East India Company, Jean-Henri-Louis Orry de Fulvy (1703–1751). In 1745 Fulvy obtained a royal privilege, giving the manufactory the exclusive right to produce porcelain “in the Saxon manner, that is, painted and gilded with human figures.” The fledgling company hoped to compete with porcelain imported from East Asia as well as that produced at the Meissen factory in Saxony, whose success was a drain on the French economy.

In 1756 the workshop moved to the town of Sèvres, halfway between Paris and Versailles. Nearby was the Château de Bellevue, built for Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), Louis XV’s mistress and a porcelain aficionado who became a powerful advocate for the manufactory. Three years later, the king became the company’s principal stockholder and took Sèvres under direct management and under the aegis of the crown. Through his patronage, Sèvres became the most important producer of soft-paste porcelain in Europe.

Ink and gouache on paper

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Manzara

Jean-Claude Duplessis

Around 1751, Jean-Claude Duplessis (ca. 1695–1774), goldsmith, sculptor, ceramic modeler, bronze-founder, and principal designer for the Vincennes workshop since 1748, created the models for a complete table service intended for Louis XV. Duplessis chose a brilliant turquoise background, named bleu céleste (celestial blue) in reference to China—the Celestial Empire. This bright new color was invented by chemist Jean Hellot (1685–1766), member of the Académie des sciences, who had just been hired by Louis XV to improve the recipes and manufacturing processes at the manufactory. Flowers in new light colors completed the decoration of this royal service.

Around 1751, Jean-Claude Duplessis (ca. 1695–1774), goldsmith, sculptor, ceramic modeler, bronze-founder, and principal designer for the Vincennes workshop since 1748, created the models for a complete table service intended for Louis XV. Duplessis chose a brilliant turquoise background, named bleu céleste (celestial blue) in reference to China—the Celestial Empire. This bright new color was invented by chemist Jean Hellot (1685–1766), member of the Académie des sciences, who had just been hired by Louis XV to improve the recipes and manufacturing processes at the manufactory. Flowers in new light colors completed the decoration of this royal service.

Les Nymphes à la coquille (Nymphs with a Shell)

In addition to his famous royal table service, Jean-Claude Duplessis père designed tableware, pieces for the consumption of hot drinks, and numerous vase forms. In September 1763, Duplessis was paid for this more technically challenging object: a “model of a group of two back-to-back female figures carrying a shell placed on an ornamental foot” (modèle d’un groupe de deux figures de femmes adossées portant une coquille placée sur un pied d’ornement), a sculpture that recalls other works Duplessis had made in silver and gilt bronze.

Madame de Pompadour, former mistress of King Louis XV, acquired a Nymphs with a Shell, possibly this one, on July 12, 1762.

In addition to his famous royal table service, Jean-Claude Duplessis père designed tableware, pieces for the consumption of hot drinks, and numerous vase forms. In September 1763, Duplessis was paid for this more technically challenging object: a “model of a group of two back-to-back female figures carrying a shell placed on an ornamental foot” (modèle d’un groupe de deux figures de femmes adossées portant une coquille placée sur un pied d’ornement), a sculpture that recalls other works Duplessis had made in silver and gilt bronze.

Madame de Pompadour, former mistress of King Louis XV, acquired a Nymphs with a Shell, possibly this one, on July 12, 1762.

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 2011.2.3

François Boucher

Of all the artists who worked at the Sèvres Manufactory during the eighteenth century, François Boucher (1703–1770) was by far the most important. He provided the models for most of the sculptures produced at Sèvres at the time, including those presented here. He designed numerous types of Enfants (then known as Enfants Boucher), sculptures of young children engaged in various, sometimes unexpectedly mature activities, as in The Drunkard. Boucher also created Pastorales, groups of nobles dressed as shepherds and shepherdesses in idyllic rural settings, a genre that enjoyed great success, as well as scenes drawn from contemporary theatrical plays.

Boucher likely played a crucial role in the development of biscuit at Sèvres. A famed painter, he was concerned about the translation of his drawings into three-dimensional objects and must have been dissatisfied with the sometimes clumsy figures originally produced at Vincennes. Possibly at Boucher’s suggestion, an experienced sculptor, Pierre Blondeau (worked at Sèvres, 1752–53), was employed to develop proper models that could be used to produce sculptures with consistent dimensions and quality.

Of all the artists who worked at the Sèvres Manufactory during the eighteenth century, François Boucher (1703–1770) was by far the most important. He provided the models for most of the sculptures produced at Sèvres at the time, including those presented here. He designed numerous types of Enfants (then known as Enfants Boucher), sculptures of young children engaged in various, sometimes unexpectedly mature activities, as in The Drunkard. Boucher also created Pastorales, groups of nobles dressed as shepherds and shepherdesses in idyllic rural settings, a genre that enjoyed great success, as well as scenes drawn from contemporary theatrical plays.

Boucher likely played a crucial role in the development of biscuit at Sèvres. A famed painter, he was concerned about the translation of his drawings into three-dimensional objects and must have been dissatisfied with the sometimes clumsy figures originally produced at Vincennes. Possibly at Boucher’s suggestion, an experienced sculptor, Pierre Blondeau (worked at Sèvres, 1752–53), was employed to develop proper models that could be used to produce sculptures with consistent dimensions and quality.

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 6566.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Thierry Ollivier

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 6566.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Thierry Ollivier

Etienne-Maurice Falconet

In 1748 the shareholders of the young Vincennes Manufactory noted that: “The sculpture workshop can achieve perfection only by placing at the head of the workshop a leader who makes the artisans work and is responsible for giving the pieces his master stroke.”

They found the ideal candidate in Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791), a sculptor and member of the Académie Royale, who had just created L’Amitié (Friendship). With the protection of Madame de Pompadour, in whose likeness this sculpture was created, Falconet was appointed head artist in charge of sculpture in 1757, a position he kept until 1766.

At Sèvres, Falconet was required to come to the workshop just one day per week. He brought new models, supervised their execution, and inspected the sculptures ready to be fired, engraving his certification—a capital F—on those that he judged to be good. This schedule allowed him to continue his private practice as a sculptor, producing work for his own clientele. There was a clear understanding that works Falconet created elsewhere could also be adapted by the Sèvres Manufactory.

Like Boucher, Falconet provided models of Enfants, for example, The Apple Eater, and designed groups representing Pastorales and theatrical plays such as The Château Celebration and Urgèle, the Fairy. He also occasionally provided models for single figures, like the famous Bather.

In 1748 the shareholders of the young Vincennes Manufactory noted that: “The sculpture workshop can achieve perfection only by placing at the head of the workshop a leader who makes the artisans work and is responsible for giving the pieces his master stroke.”

They found the ideal candidate in Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791), a sculptor and member of the Académie Royale, who had just created L’Amitié (Friendship). With the protection of Madame de Pompadour, in whose likeness this sculpture was created, Falconet was appointed head artist in charge of sculpture in 1757, a position he kept until 1766.

At Sèvres, Falconet was required to come to the workshop just one day per week. He brought new models, supervised their execution, and inspected the sculptures ready to be fired, engraving his certification—a capital F—on those that he judged to be good. This schedule allowed him to continue his private practice as a sculptor, producing work for his own clientele. There was a clear understanding that works Falconet created elsewhere could also be adapted by the Sèvres Manufactory.

Like Boucher, Falconet provided models of Enfants, for example, The Apple Eater, and designed groups representing Pastorales and theatrical plays such as The Château Celebration and Urgèle, the Fairy. He also occasionally provided models for single figures, like the famous Bather.

In 1748 the shareholders of the young Vincennes Manufactory noted that: “The sculpture workshop can achieve perfection only by placing at the head of the workshop a leader who makes the artisans work and is responsible for giving the pieces his master stroke.”

They found the ideal candidate in Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791), a sculptor and member of the Académie Royale, who had just created L’Amitié (Friendship). With the protection of Madame de Pompadour, in whose likeness this sculpture was created, Falconet was appointed head artist in charge of sculpture in 1757, a position he kept until 1766.

At Sèvres, Falconet was required to come to the workshop just one day per week. He brought new models, supervised their execution, and inspected the sculptures ready to be fired, engraving his certification—a capital F—on those that he judged to be good. This schedule allowed him to continue his private practice as a sculptor, producing work for his own clientele. There was a clear understanding that works Falconet created elsewhere could also be adapted by the Sèvres Manufactory.

Like Boucher, Falconet provided models of Enfants, for example, The Apple Eater, and designed groups representing Pastorales and theatrical plays such as The Château Celebration and Urgèle, the Fairy. He also occasionally provided models for single figures, like the famous Bather.

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 25220

Photo: Bruce M. White

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 3123

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

![L’Amour (Falconet) (Cupid [Falconet]) A white marble statue depicts a young cherub with wings, seated on a rock. The cherub has one finger raised to its lips, suggesting a shushing gesture. The intricately detailed figure showcases classical artistry in its form and features.](https://exhibitions.bgc.bard.edu/sevres/files/2024/09/SS-013copy-02.jpg)

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 27724.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 25220

Photo: Bruce M. White

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 3123

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

![L’Amour (Falconet) (Cupid [Falconet]) A white marble statue depicts a young cherub with wings, seated on a rock. The cherub has one finger raised to its lips, suggesting a shushing gesture. The intricately detailed figure showcases classical artistry in its form and features.](https://exhibitions.bgc.bard.edu/sevres/files/2024/09/SS-013copy-02.jpg)

Soft-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 27724.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

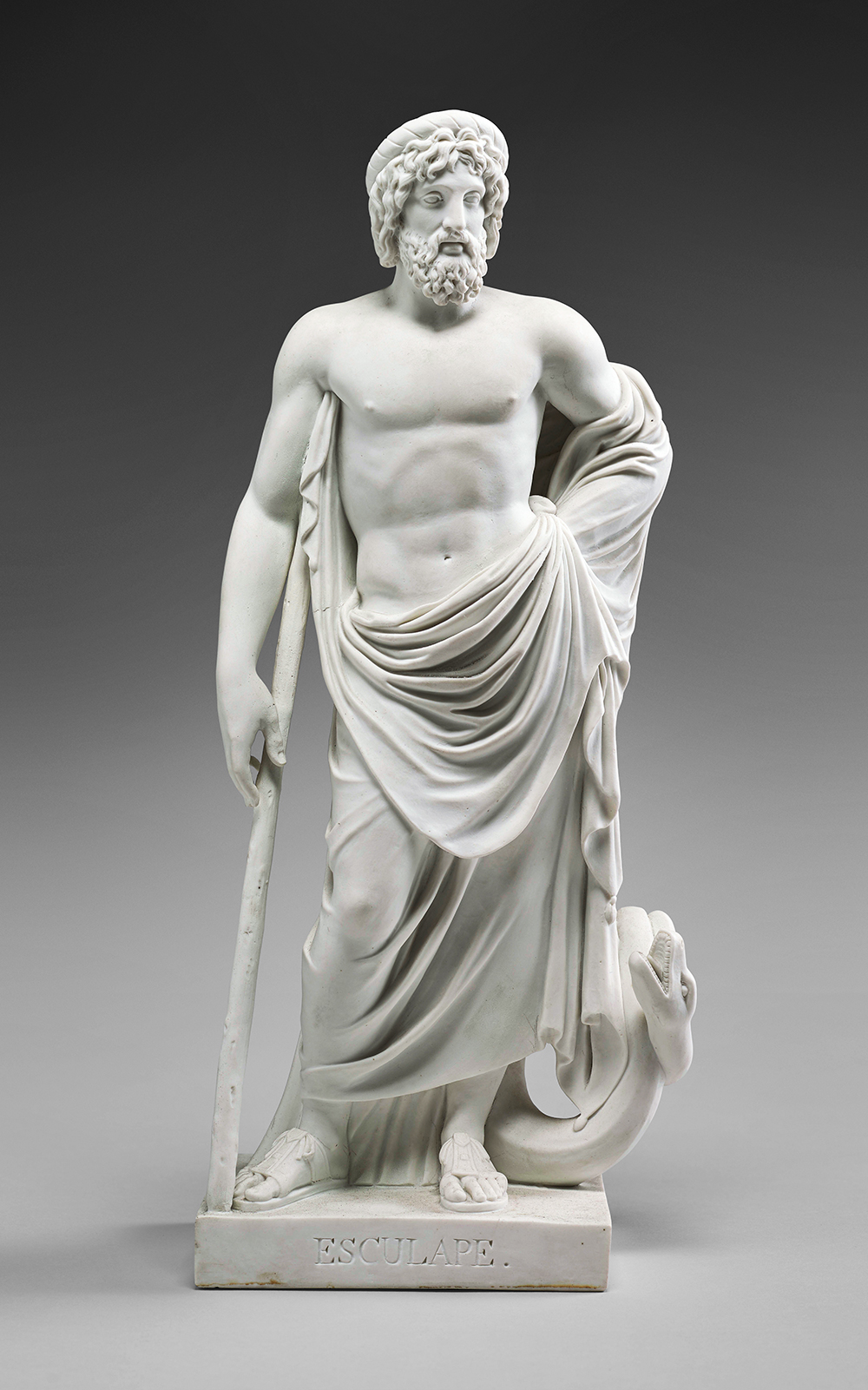

Louis-Simon Boizot

The manufactory’s new administrator, Melchior-François Parent (1716–1782), made an unexpected hiring decision in 1773. For the position of “head artist in charge of sculpture,” Parent recruited Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809), a young sculptor only recently admitted to the Académie Royale. Perhaps this choice was influenced by Boizot’s working relationship with the comtesse Du Barry (1743–1793), mistress to Louis XV (r. 1715–74). It was nevertheless a successful hire, and Boizot retained his position for twenty-seven years, guiding Sèvres through a fruitful, prosperous period and then a tumultuous one.

Like his immediate predecessors as head artist, Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), Boizot designed vases and table services and provided models for groups and figures. Like Falconet, Boizot was able to continue his own career as a sculptor, exhibiting works at the annual Salon organized by the Académie Royale, some of which were adapted for use at Sèvres. Boizot recommended that the manufactory hire many other sculptors to assist him, including several of his students at the Académie as well as Jacques-Auguste Collet.

Boizot presided over Sèvres during the French Revolution, although he was absent for a period between 1792 and 1793, leaving the sculptors without their head artist. Influenced by revolutionary ideals, some young workers left to fight or serve on committees in the town of Sèvres, but most older artists remained, insulating the manufactory from the worst of the upheaval. Production was limited, but it continued. At first, smaller objects proliferated; later, busts and portraits—especially in the form of medallions—were almost all that went into the kilns. During the months of the Terror, production consisted almost entirely of portraits of the heroes and martyrs of the day. Beginning in 1798, the vast majority of sales were busts and medallions representing Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821).

The manufactory’s new administrator, Melchior-François Parent (1716–1782), made an unexpected hiring decision in 1773. For the position of “head artist in charge of sculpture,” Parent recruited Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809), a young sculptor only recently admitted to the Académie Royale. Perhaps this choice was influenced by Boizot’s working relationship with the comtesse Du Barry (1743–1793), mistress to Louis XV (r. 1715–74). It was nevertheless a successful hire, and Boizot retained his position for twenty-seven years, guiding Sèvres through a fruitful, prosperous period and then a tumultuous one.

Like his immediate predecessors as head artist, Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), Boizot designed vases and table services and provided models for groups and figures. Like Falconet, Boizot was able to continue his own career as a sculptor, exhibiting works at the annual Salon organized by the Académie Royale, some of which were adapted for use at Sèvres. Boizot recommended that the manufactory hire many other sculptors to assist him, including several of his students at the Académie as well as Jacques-Auguste Collet.

Boizot presided over Sèvres during the French Revolution, although he was absent for a period between 1792 and 1793, leaving the sculptors without their head artist. Influenced by revolutionary ideals, some young workers left to fight or serve on committees in the town of Sèvres, but most older artists remained, insulating the manufactory from the worst of the upheaval. Production was limited, but it continued. At first, smaller objects proliferated; later, busts and portraits—especially in the form of medallions—were almost all that went into the kilns. During the months of the Terror, production consisted almost entirely of portraits of the heroes and martyrs of the day. Beginning in 1798, the vast majority of sales were busts and medallions representing Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821).

The manufactory’s new administrator, Melchior-François Parent (1716–1782), made an unexpected hiring decision in 1773. For the position of “head artist in charge of sculpture,” Parent recruited Louis-Simon Boizot (1743–1809), a young sculptor only recently admitted to the Académie Royale. Perhaps this choice was influenced by Boizot’s working relationship with the comtesse Du Barry (1743–1793), mistress to Louis XV (r. 1715–74). It was nevertheless a successful hire, and Boizot retained his position for twenty-seven years, guiding Sèvres through a fruitful, prosperous period and then a tumultuous one.

Like his immediate predecessors as head artist, Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791) and Jean Jacques Bachelier (1724–1806), Boizot designed vases and table services and provided models for groups and figures. Like Falconet, Boizot was able to continue his own career as a sculptor, exhibiting works at the annual Salon organized by the Académie Royale, some of which were adapted for use at Sèvres. Boizot recommended that the manufactory hire many other sculptors to assist him, including several of his students at the Académie as well as Jacques-Auguste Collet.

Boizot presided over Sèvres during the French Revolution, although he was absent for a period between 1792 and 1793, leaving the sculptors without their head artist. Influenced by revolutionary ideals, some young workers left to fight or serve on committees in the town of Sèvres, but most older artists remained, insulating the manufactory from the worst of the upheaval. Production was limited, but it continued. At first, smaller objects proliferated; later, busts and portraits—especially in the form of medallions—were almost all that went into the kilns. During the months of the Terror, production consisted almost entirely of portraits of the heroes and martyrs of the day. Beginning in 1798, the vast majority of sales were busts and medallions representing Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821).

Wax on plaster (left), blue and white hard-paste porcelain biscuit (right)

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 21710; MNC 15604

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Thierry Ollivier; Photo: Bruce M. White

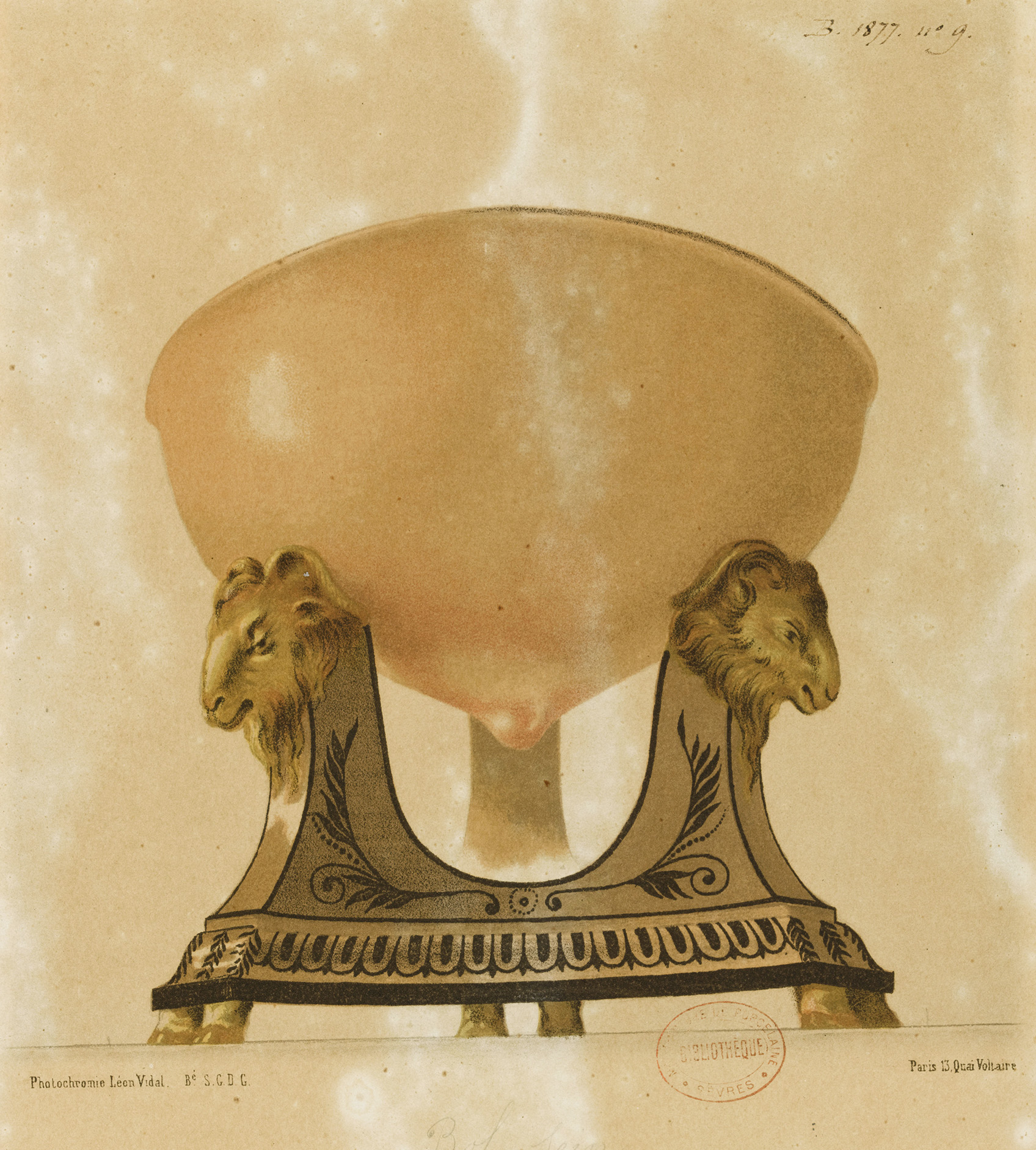

Bol sein et Trépied (Breast Bowl and Tripod)

This breast bowl, sometimes known as a jatte téton, is the most striking piece of a luxurious and innovative service created at Sèvres for Queen Marie-Antoinette’s dairy— an idyllic rural retreat for preparing and consuming dairy products. The bowl is inspired by an ancient form, the mastos, a drinking cup in the shape of a breast. Without a “foot” to rest on, the cup is supported by a tripod in the Neoclassical style, resplendent in a palette of pastel colors. Contrary to legend, the cup was never molded on the queen’s breast.

This breast bowl, sometimes known as a jatte téton, is the most striking piece of a luxurious and innovative service created at Sèvres for Queen Marie-Antoinette’s dairy— an idyllic rural retreat for preparing and consuming dairy products. The bowl is inspired by an ancient form, the mastos, a drinking cup in the shape of a breast. Without a “foot” to rest on, the cup is supported by a tripod in the Neoclassical style, resplendent in a palette of pastel colors. Contrary to legend, the cup was never molded on the queen’s breast.

Glazed and decorated soft-paste porcelain bowl and glazed and decorated hard-paste porcelain tripod

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 23399

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

Glazed and decorated soft-paste porcelain bowl and glazed and decorated hard-paste porcelain tripod

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 23399

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

Antislavery Medallion

In the spring of 1789, the Sèvres Manufactory created a medallion that communicated a powerful antislavery message. It was inspired by a similar medallion produced by British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) just two years earlier. Wedgwood’s version became a popular icon of the antislavery movement in the English-speaking world, displayed by thousands of abolitionists. Yet production of the Sèvres medallion was halted after only fifteen objects were completed due to fears that it would lead to insurrections amongst enslaved people in France’s colonies.

In the spring of 1789, the Sèvres Manufactory created a medallion that communicated a powerful antislavery message. It was inspired by a similar medallion produced by British ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) just two years earlier. Wedgwood’s version became a popular icon of the antislavery movement in the English-speaking world, displayed by thousands of abolitionists. Yet production of the Sèvres medallion was halted after only fifteen objects were completed due to fears that it would lead to insurrections amongst enslaved people in France’s colonies.

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

Princeton University Art Museum, Trumbull-Prime Collection (y931)

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

Princeton University Art Museum, Trumbull-Prime Collection (y931)

Jump to: