19th Century

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the Sèvres Manufactory flourished under the directorship of Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who saw the institution through a period of political shifts between the Revolution, Empire, and back to monarchy. After Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned emperor, Sèvres was almost exclusively occupied with imperial commissions, including the decoration of imperial palaces and the production of large dinner services and impressive diplomatic gifts. Under Napoleon’s successors, Louis XVIII (r. 1814–24), Charles X (r. 1824–30), and Louis-Philippe (r. 1830–48), tastes changed and state commissions were sparse. The pure Neoclassical style in fashion around 1800 was followed by a Gothic revival in the 1820s, a reinterpretation of medieval aesthetics. Under Louis-Phillipe, Renaissance and Romantic styles rose to prominence. New styles did not, however, replace the previous ones and Neoclassical pieces were still produced when Gothic or Renaissance were all the rage.

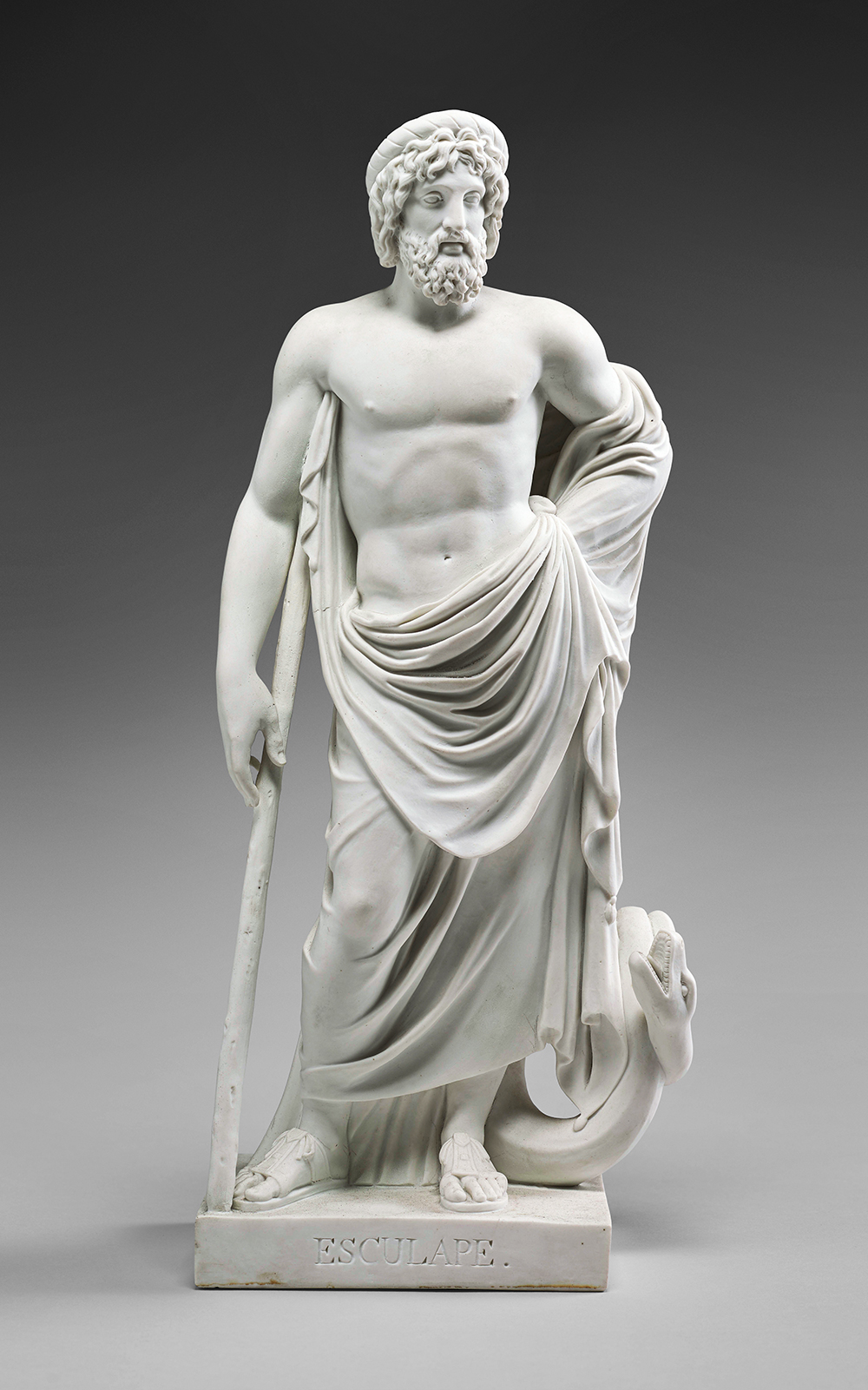

Soon after Brongniart’s death in 1847, the Second Republic was replaced by the Second Empire. The new imperial couple, Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, shared the period’s dominant taste for small sculpture, and Sèvres increased its production of new models to meet this demand. Former models were rediscovered and revived, including shapes from the manufactory’s earliest years that had been neglected during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Watercolor on card

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, 12-523441

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Watercolor on paper

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, Pp§4.1848.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Stéphane Maréchalle

19th Century

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the Sèvres Manufactory flourished under the directorship of Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who saw the institution through a period of political shifts between the Revolution, Empire, and back to monarchy. After Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned emperor, Sèvres was almost exclusively occupied with imperial commissions, including the decoration of imperial palaces and the production of large dinner services and impressive diplomatic gifts. Under Napoleon’s successors, Louis XVIII (r. 1814–24), Charles X (r. 1824–30), and Louis-Philippe (r. 1830–48), tastes changed and state commissions were sparse. The pure Neoclassical style in fashion around 1800 was followed by a Gothic revival in the 1820s, a reinterpretation of medieval aesthetics. Under Louis-Phillipe, Renaissance and Romantic styles rose to prominence. New styles did not, however, replace the previous ones and Neoclassical pieces were still produced when Gothic or Renaissance were all the rage.

Soon after Brongniart’s death in 1847, the Second Republic was replaced by the Second Empire. The new imperial couple, Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, shared the period’s dominant taste for small sculpture, and Sèvres increased its production of new models to meet this demand. Former models were rediscovered and revived, including shapes from the manufactory’s earliest years that had been neglected during the first half of the nineteenth century.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the Sèvres Manufactory flourished under the directorship of Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who saw the institution through a period of political shifts between the Revolution, Empire, and back to monarchy. After Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned emperor, Sèvres was almost exclusively occupied with imperial commissions, including the decoration of imperial palaces and the production of large dinner services and impressive diplomatic gifts. Under Napoleon’s successors, Louis XVIII (r. 1814–24), Charles X (r. 1824–30), and Louis-Philippe (r. 1830–48), tastes changed and state commissions were sparse. The pure Neoclassical style in fashion around 1800 was followed by a Gothic revival in the 1820s, a reinterpretation of medieval aesthetics. Under Louis-Phillipe, Renaissance and Romantic styles rose to prominence. New styles did not, however, replace the previous ones and Neoclassical pieces were still produced when Gothic or Renaissance were all the rage.

Soon after Brongniart’s death in 1847, the Second Republic was replaced by the Second Empire. The new imperial couple, Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, shared the period’s dominant taste for small sculpture, and Sèvres increased its production of new models to meet this demand. Former models were rediscovered and revived, including shapes from the manufactory’s earliest years that had been neglected during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Watercolor on card

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, 12-523441

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Watercolor on paper

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Alexandre Brongniart

The French Revolution and the abolition of the monarchy left the Sèvres Manufactory in a deplorable situation. In 1800 Lucien Bonaparte (1775–1840), brother of Napoleon Bonaparte and his minister of the interior, took action to restore the manufactory’s luster. He appointed as director a young scientist named Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who kept this position until his death. Although he had no previous experience in management or ceramic production, Brongniart was a remarkable administrator. He took a methodical approach to collecting ceramics from all over the world that led to technical innovations and to the reinterpretation of historical and foreign forms. Furthermore, as the son of architect Alexandre Théodore Brongniart (1739–1813), he had frequent contact with prominent artists and designers, from whom he purchased new projects. Brongniart’s approach was highly successful; within just a few years, the manufactory’s financial situation improved.

The July Revolution of 1830, which ushered in the regime of Louis-Phillipe I, corresponded to a marked change of style at the manufactory. Brongniart called upon newly hired artists to revitalize the manufactory’s repertoire of shapes; one was designer Claude-Aimé Chenavard (worked at Sèvres, 1829–37). During this time, color made a remarkable resurgence in a variety of Renaissance-inspired sculptures, especially in low relief.

The French Revolution and the abolition of the monarchy left the Sèvres Manufactory in a deplorable situation. In 1800 Lucien Bonaparte (1775–1840), brother of Napoleon Bonaparte and his minister of the interior, took action to restore the manufactory’s luster. He appointed as director a young scientist named Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who kept this position until his death. Although he had no previous experience in management or ceramic production, Brongniart was a remarkable administrator. He took a methodical approach to collecting ceramics from all over the world that led to technical innovations and to the reinterpretation of historical and foreign forms. Furthermore, as the son of architect Alexandre Théodore Brongniart (1739–1813), he had frequent contact with prominent artists and designers, from whom he purchased new projects. Brongniart’s approach was highly successful; within just a few years, the manufactory’s financial situation improved.

The July Revolution of 1830, which ushered in the regime of Louis-Phillipe I, corresponded to a marked change of style at the manufactory. Brongniart called upon newly hired artists to revitalize the manufactory’s repertoire of shapes; one was designer Claude-Aimé Chenavard (worked at Sèvres, 1829–37). During this time, color made a remarkable resurgence in a variety of Renaissance-inspired sculptures, especially in low relief.

The French Revolution and the abolition of the monarchy left the Sèvres Manufactory in a deplorable situation. In 1800 Lucien Bonaparte (1775–1840), brother of Napoleon Bonaparte and his minister of the interior, took action to restore the manufactory’s luster. He appointed as director a young scientist named Alexandre Brongniart (1770–1847), who kept this position until his death. Although he had no previous experience in management or ceramic production, Brongniart was a remarkable administrator. He took a methodical approach to collecting ceramics from all over the world that led to technical innovations and to the reinterpretation of historical and foreign forms. Furthermore, as the son of architect Alexandre Théodore Brongniart (1739–1813), he had frequent contact with prominent artists and designers, from whom he purchased new projects. Brongniart’s approach was highly successful; within just a few years, the manufactory’s financial situation improved.

The July Revolution of 1830, which ushered in the regime of Louis-Phillipe I, corresponded to a marked change of style at the manufactory. Brongniart called upon newly hired artists to revitalize the manufactory’s repertoire of shapes; one was designer Claude-Aimé Chenavard (worked at Sèvres, 1829–37). During this time, color made a remarkable resurgence in a variety of Renaissance-inspired sculptures, especially in low relief.

Écritoire égyptienne (Egyptian Inkstand)

The Sèvres Manufactory made two ink-stands of this model, one with gold decoration (shown here) and one without it. Very little is known about them: no archival documentation or preparatory drawings have been preserved. They were made in 1802, the year following the end of France’s so-called Egyptian Campaign, in which Napoleon Bonaparte’s army invaded Egypt and Syria accompanied by many prominent scholars, including archaeologists, engineers, and scientists.

Like many decorative objects from this period, these inkstands are inspired by antique styles without faithfully reproducing their sources. It was only after the publication in 1802 of the Voyage dans la Basse et dans la Haute Égypte (Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt) by Dominique-Vivant Denon (1747–1825), an artist, diplomat, and archaeologist, that French decorative objects featured more accurate representations of Egyptian art and hieroglyphic writing.

The Sèvres Manufactory made two ink-stands of this model, one with gold decoration (shown here) and one without it. Very little is known about them: no archival documentation or preparatory drawings have been preserved. They were made in 1802, the year following the end of France’s so-called Egyptian Campaign, in which Napoleon Bonaparte’s army invaded Egypt and Syria accompanied by many prominent scholars, including archaeologists, engineers, and scientists.

Like many decorative objects from this period, these inkstands are inspired by antique styles without faithfully reproducing their sources. It was only after the publication in 1802 of the Voyage dans la Basse et dans la Haute Égypte (Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt) by Dominique-Vivant Denon (1747–1825), an artist, diplomat, and archaeologist, that French decorative objects featured more accurate representations of Egyptian art and hieroglyphic writing.

“Pâte bronze” hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 2648

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

“Pâte bronze” hard-paste porcelain biscuit with gilding

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 2648

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

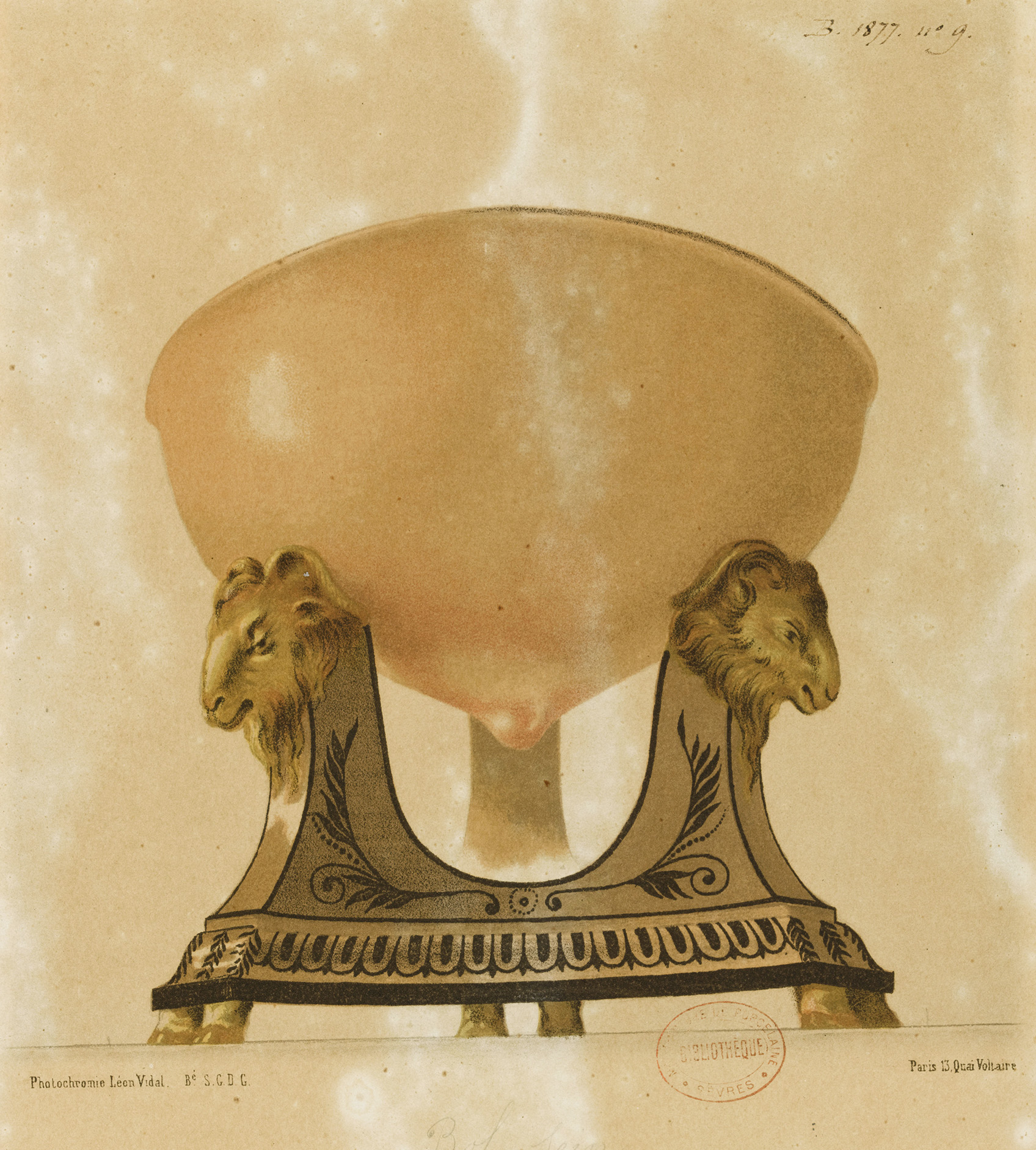

Sucrier Argonaute (Argonaut Sugar Bowl)

This object faithfully copies the “shell” (actually an egg case) of an argonaut, a distinct genus of octopus and distant relative of the nautilus. This form was first produced in 1810 as an inkstand and a lamp and then transformed into a sugar bowl. The bright purple color makes it particularly appealing, but the manufactory also produced examples in white and gold. Curiously, the argonaut egg case closely resembles the shell of an extinct ammonite, which might explain its appeal to its probable creator, Alexandre Brongniart, an accomplished scientist who had studied both zoology and paleontology.

This object faithfully copies the “shell” (actually an egg case) of an argonaut, a distinct genus of octopus and distant relative of the nautilus. This form was first produced in 1810 as an inkstand and a lamp and then transformed into a sugar bowl. The bright purple color makes it particularly appealing, but the manufactory also produced examples in white and gold. Curiously, the argonaut egg case closely resembles the shell of an extinct ammonite, which might explain its appeal to its probable creator, Alexandre Brongniart, an accomplished scientist who had studied both zoology and paleontology.

Glazed and decorated hard paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 2022.4.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Sylvie Chan-Liat

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

Vase de la Renaissance (Renaissance Vase)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard provided many new designs for the Sèvres Manufactory, not only for table services and vases but also for novel types of decorations. Fragonard was an excellent draftsman and a capable sculptor, responsible for both the drawing and the model for this Renaissance Vase.

While the preparatory drawing clearly evokes the spirit of the Renaissance, the gold and matte biscuit decoration of this extraordinary object exemplifies the liberty with which nineteenth-century artists interpreted historical models.

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard provided many new designs for the Sèvres Manufactory, not only for table services and vases but also for novel types of decorations. Fragonard was an excellent draftsman and a capable sculptor, responsible for both the drawing and the model for this Renaissance Vase.

While the preparatory drawing clearly evokes the spirit of the Renaissance, the gold and matte biscuit decoration of this extraordinary object exemplifies the liberty with which nineteenth-century artists interpreted historical models.

Graphite, ink, and watercolor on paper

Inscription [recto, bottom, in the handwriting of Denis Désiré Riocreux]: Vase dans le style de la Renaissance/par Mr Fragonard (aout 1832)

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.3.745/D §8 1832 n°5

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Le Studio Numérique

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit, partly glazed and gilded

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 24963

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

Graphite, ink, and watercolor on paper

Inscription [recto, bottom, in the handwriting of Denis Désiré Riocreux]: Vase dans le style de la Renaissance/par Mr Fragonard (aout 1832)

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.3.745/D §8 1832 n°5

Photo © Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Le Studio Numérique

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit, partly glazed and gilded

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 24963

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Tony Querrec

Pot à crème Tête de vache (Cow’s Head Cream Jug)

This highly original cream jug, whose form derives from an ancient drinking horn known as a rhyton, is one of many collaborations between sculptor and painter Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard (worked at Sèvres, 1805–42), son of the celebrated eighteenth-century painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), and the sculptor Jean Charles Nicolas Brachard (Brachard aîné). Fragonard provided the drawing while Brachard aîné translated it into a three-dimensional model. Like many vessels that adapt this ancient form, the jug is ornamented with the head of a cow in reference to the container’s intended contents.

This highly original cream jug, whose form derives from an ancient drinking horn known as a rhyton, is one of many collaborations between sculptor and painter Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard (worked at Sèvres, 1805–42), son of the celebrated eighteenth-century painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), and the sculptor Jean Charles Nicolas Brachard (Brachard aîné). Fragonard provided the drawing while Brachard aîné translated it into a three-dimensional model. Like many vessels that adapt this ancient form, the jug is ornamented with the head of a cow in reference to the container’s intended contents.

Glazed and decorated hard-paste porcelain

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 2022.5.1

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Click to enlarge gallery images.

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse

Sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse was director of artworks at Sèvres from 1876 until 1887. He designed an impressive number of new shapes, mainly for vases. Some of these had smooth surfaces on which decorators could express their creativity, like the Saïgon Vase with decoration by Auguste Rodin. Other vases were ornamented, either with sculptural details or with figures. Carrier-Belleuse also created functional wares and traditional sculptures.

Sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse was director of artworks at Sèvres from 1876 until 1887. He designed an impressive number of new shapes, mainly for vases. Some of these had smooth surfaces on which decorators could express their creativity, like the Saïgon Vase with decoration by Auguste Rodin. Other vases were ornamented, either with sculptural details or with figures. Carrier-Belleuse also created functional wares and traditional sculptures.

République, bust

In 1883, more than a decade after the establishment of the Third Republic, Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse designed a very small seated figure of La République, an allegorical figure representing the Republic, for the cover of a Vase Ledoux Patriotique, which he subsequently enlarged. In 1884, to accommodate the wishes of the manufactory’s director, Charles Lauth, he once more adjusted the model, producing the final version presented here.

This figure wears the Phrygian cap, which was adopted as a symbol of liberty and republicanism during the French Revolution, and armor emblazoned with the head of Medusa, symbolic of victory. Inscribed on the stand are RF for République Française and LA LOI, affirming the importance of the law, rather than the rule of kings or emperors, for both France and the Sèvres Manufactory.

In 1883, more than a decade after the establishment of the Third Republic, Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse designed a very small seated figure of La République, an allegorical figure representing the Republic, for the cover of a Vase Ledoux Patriotique, which he subsequently enlarged. In 1884, to accommodate the wishes of the manufactory’s director, Charles Lauth, he once more adjusted the model, producing the final version presented here.

This figure wears the Phrygian cap, which was adopted as a symbol of liberty and republicanism during the French Revolution, and armor emblazoned with the head of Medusa, symbolic of victory. Inscribed on the stand are RF for République Française and LA LOI, affirming the importance of the law, rather than the rule of kings or emperors, for both France and the Sèvres Manufactory.

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.610

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Hervé Lewandowski

Click to enlarge gallery images.

Hard-paste porcelain biscuit

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNS 2011.D.610

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Hervé Lewandowski

Saïgon Vase

Sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse designed this Saïgon Vase with a smooth surface, leaving ample space for the skill and imagination of decorator Auguste Rodin. In June 1879 Carrier-Belleuse invited Rodin, who had been his student, to work at Sèvres as a modeler, work he continued until 1882. Despite working part-time, in a period of only a few months Rodin decorated eighteen vases and developed a new technique that allowed him to engrave directly in the raw paste while also adding relief. On this vase, he used this technique to depict allegories of the elements featuring infants.

Sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse designed this Saïgon Vase with a smooth surface, leaving ample space for the skill and imagination of decorator Auguste Rodin. In June 1879 Carrier-Belleuse invited Rodin, who had been his student, to work at Sèvres as a modeler, work he continued until 1882. Despite working part-time, in a period of only a few months Rodin decorated eighteen vases and developed a new technique that allowed him to engrave directly in the raw paste while also adding relief. On this vase, he used this technique to depict allegories of the elements featuring infants.

Glazed and decorated hard-paste porcelain with a bronze mount

Manufacture et Musée nationaux, Sèvres, MNC 8984

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres – Manufacture et musée nationaux) / Martine Beck-Coppola

Jump to: