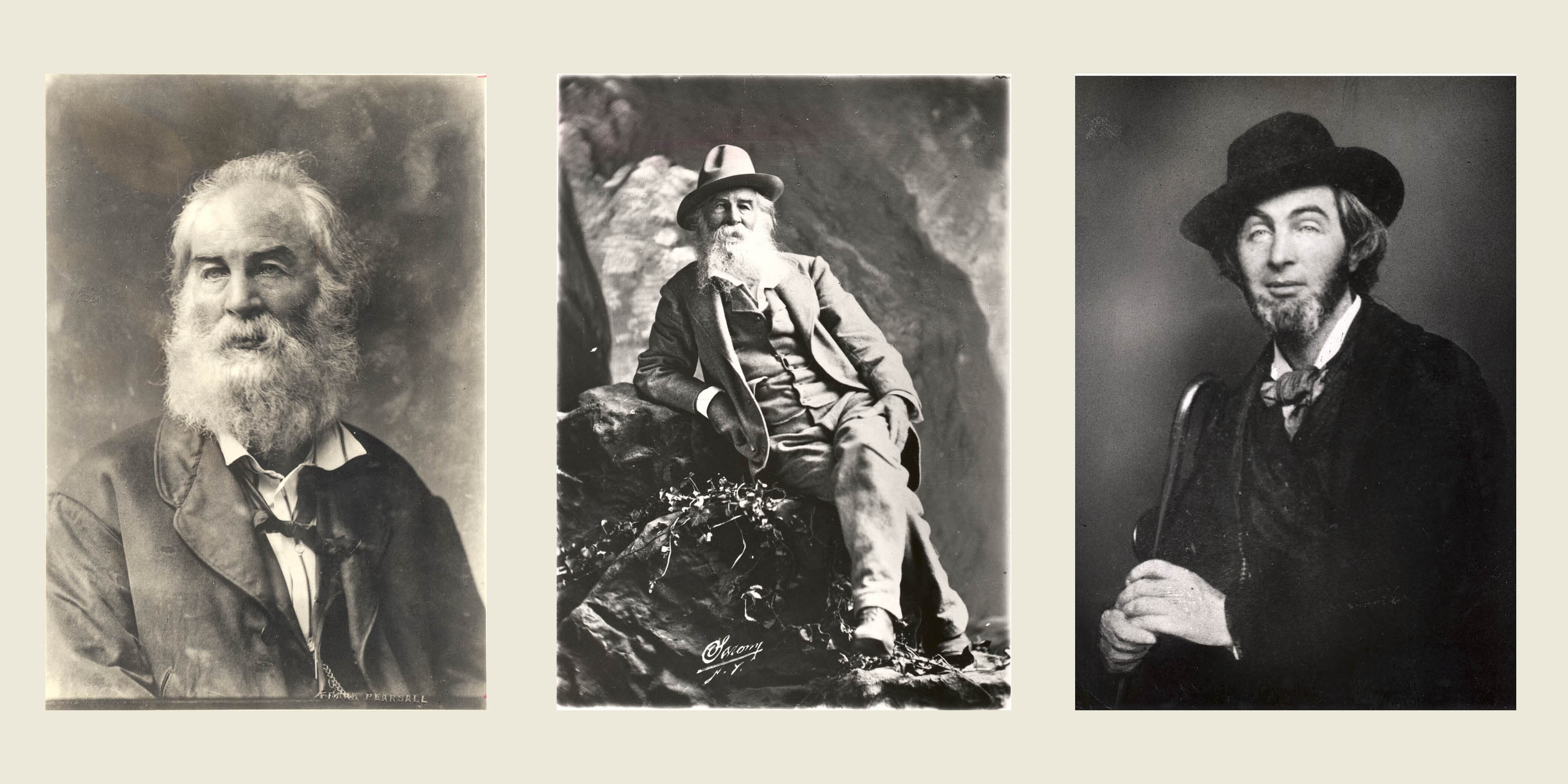

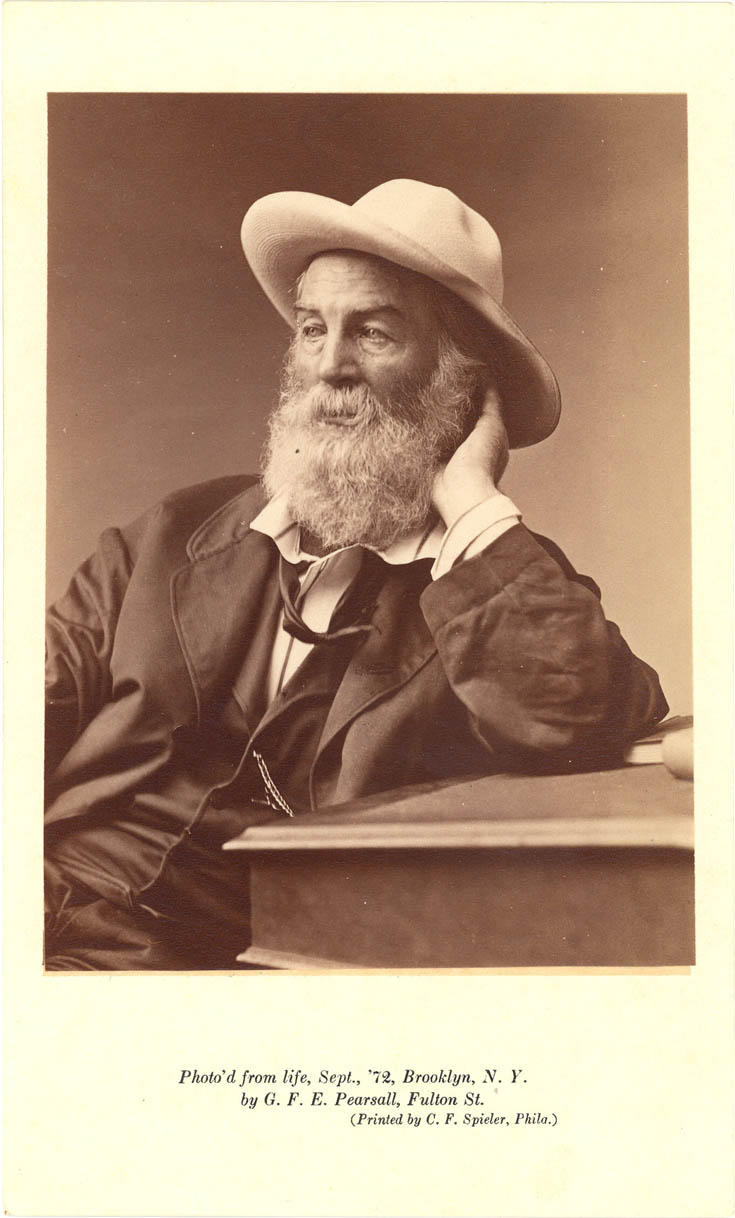

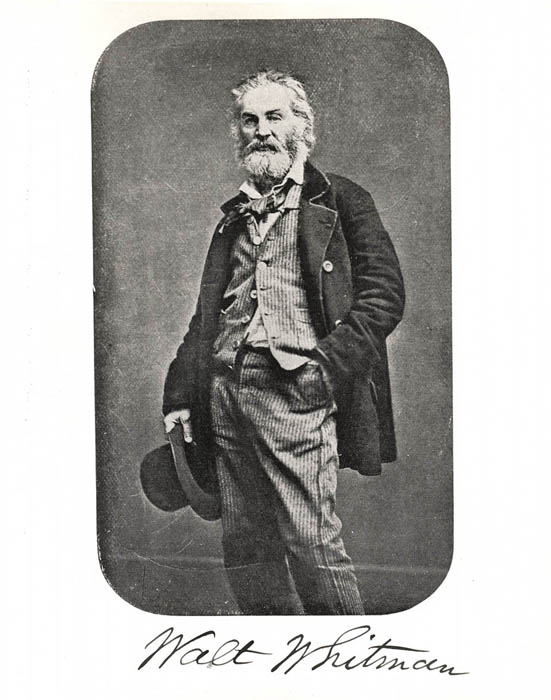

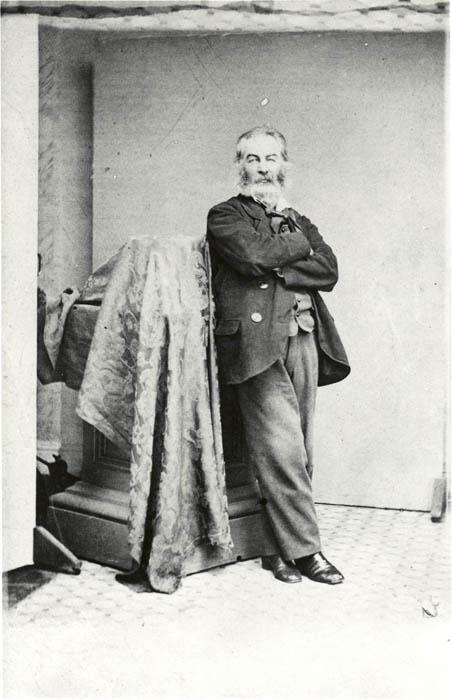

Dressing the Body of the Poet

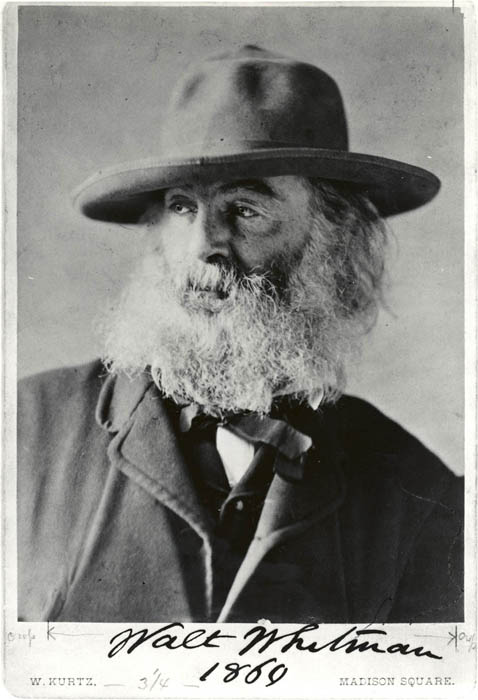

Walt Whitman was one of the most photographed American authors of the nineteenth century, and so often sat to have his portrait taken that upon rediscovering images of himself he had forgotten about, remarked, “I meet new Walt Whitmans every day. There are a dozen of me afloat…” The more than one hundred surviving images of Whitman taken throughout his life not only provide a record of the author’s changing physical characteristics, but also constitute a rich record of the clothing he wore. Whitman’s unique sartorial choices are represented in these photographs, from his “sauce-pan” hat and open shirt collar to his wide “bloomer” pants. Whitman often wrote about his clothing in letters to friends and family, and kept his mother in particular informed of the condition of his clothes and told her of new garments he purchased.

Many of Whitman’s acquaintances commented on his unique appearance which in many ways departed from the accepted image of a fashionable nineteenth-century gentleman. Among these comments is a particularly descriptive note written by Bronson Alcott upon visiting Whitman at his home in Brooklyn:

Broad-shouldered, rouge-fleshed, Bacchus-browed, bearded like a satyr, and rank, he wears his man-Bloomer in defiance of everybody, having these as everything else after his own fashion, and for example to all men hereafter. Red flannel undershirt, open-breasted, exposing his brawny neck; striped calico jacket over this, the collar Byroneal, with coarse cloth overalls buttoned to it; cowhide boots; a heavy round-about, with huge outside pockets and buttons to match; and a slouched hat, for house and street alike. Eyes gray, un-imaginative, cautious yet sagacious; his voice deep, sharp, tender sometimes and almost melting…

– Bronson Alcott, 1856

The photographs below were taken in New York between 1848 and 1878 and present Whitman’s easily recognizable image. Upon closer inspection, and when paired with Whitman’s writing about his clothing, these images can provide useful details that help to illuminate how the poet wished to present himself.